Wheezing is the most common symptom associated with asthma in young children. There is a lack of well-designed prospective studies on the relationship of exclusive breastfeeding with wheezing in infants. This prospective cohort study investigated whether a relationship exists of exclusive breastfeeding with wheezing at 12 months of age.

Materials and methodsA series of 1632 mother–infant pairs were sequentially recruited. Mothers were trained at hospital on breastfeeding practices and how to recognise wheezing. At hospital discharge they received a calendar-diary to record the date at stopping breastfeeding and at onset of wheezing. Data were collected by telephone interviews through 12 months post-delivery. Breastfeeding was in accordance with the World Health Organisation and wheezing with the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10-CM code R06.2).

ResultsAt 12 months 1522 mother–infant pairs were participating. Breastfeeding started in 95.9% of them and was exclusive in 86.1%. The incidence of wheezing ever and recurrent wheezing at 12 months of age was 33.7% and 10.0%, respectively. Duration of exclusive breastfeeding was shorter in wheezing than non-wheezing infants (median 2.6 months vs. 4.1 months, P<0.001). After adjustment for confounders each month of exclusive breastfeeding reduced the risk of wheezing ever by 11% and of recurrent wheezing by 15%, at 12 months of age.

ConclusionLonger duration of exclusive breastfeeding reduces the risk of wheezing throughout the first 12 months of life. These findings would be relevant to all healthcare operators and mothers, also to improve their awareness about the best feeding practices for the infant's health.

Exclusive breastfeeding is the preferred feeding method during the first six months of life1,2 and provides all the energy and nutrients infants need in this period.3 Breastfeeding offers heath advantages for infants and mothers2 and may benefit the respiratory tract of the young child,2,4–6 possibly also reducing the risk of asthma.5,6

Wheezing is the most common symptom associated with asthma in children aged five years or younger7 with high prevalence worldwide, ranging from approximately 25% to 50% in the first year of life.8,9 It has been reported that early wheezing could increase the risk of respiratory morbidity in infancy10 and young adulthood,11 implying a cost burden.2,8,9,12 Identifying factors associated with wheezing in early life can therefore be of clinical and social relevance.

After the Tucson research started in the late 1980s,13 studies have evaluated the relationship of breastfeeding with wheezing in early age (e.g.,4,5,14–16) and systematic reviews support that breastfeeding is protective against asthma and wheezing in young children.6,17–19 Silver et al.4 found that the duration of exclusive breastfeeding was a stronger determinant of respiratory outcomes, including wheezing, than “any” breastfeeding at 15 months of age. Indeed, the relationship between exclusive breastfeeding and wheezing and/or other asthma-related outcomes has been scantily studied so far,4,20–25 possibly due to the complexity to conduct cohort studies collecting accurate data on infant feeding, prospectively. There is a need for studies based on large cohorts, strict eligibility criteria and definitions, longitudinal and accurate data, including continuous measurement of breastfeeding, while taking into account a minimum set of confounders.2,4–6,12–19

This study was conducted on the basis of these recommendations with the aim of assessing if a relationship exists of exclusive breastfeeding with wheezing during the first year of life in at term healthy newborns.

Materials and methodsIn this prospective cohort study, 1632 mother–infant pairs were sequentially recruited at the San Paolo Hospital in Milan, Italy, between September 1st, 2013, and August 31st, 2014, according to the following eligibility criteria. Inclusion criteria were: gestational age within 37–42 completed weeks, weight at birth equal or above 2500g and lower than 4000g, single birth, absence of congenital anomalies, mother speaking Italian, family living within a 15km distance to hospital. Exclusion criteria were: infant dead at the maternity ward, infant moved to another hospital/clinic, infant with galactosemia or other inherited metabolic disorders or disease requiring hospitalisation longer than seven days, maternal conditions under which breastfeeding may not be in the best interest of the infant.2 Mothers and infants were checked for eligibility at the maternity ward, and willing women signed a consent to participate in the study. All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible ethics committee which approved the study.

Data collectionExperienced neonatologists saw the infants and took anthropometric measurements within 12h of birth using an electronic scale (Seca Digital Baby Scale Model 376, Seca GmbH & Co. KG, Hamburg, Germany) for weight and the Harpenden infantometer (Chasmors Ltd, London, UK) for recumbent length, following standardised procedures. Socio-demographic characteristics and medical history were collected during the hospital stay. Pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) was calculated from self-reported body weight before pregnancy and height measured at the hospital using a Seca integrated measuring rod (model 704s, Seca GmbH & Co. KG). A woman was defined underweight, normal weight, overweight or obese in accordance with the World Health Organisation (WHO).26 Wheezing was defined in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM code 786.07 now translated to ICD-10-CM code R06.2) as a high-pitched, whistling sound during breathing, resulting from the narrowing or obstruction of the respiratory airways.27 The breastfeeding practices were in accordance with the WHO as updated in 2007.28 “Any” breastfeeding was defined as the feeding practice requiring that the infant receives breast milk (including milk expressed or from a wet nurse) and allows the infant to receive anything else. “Initiation” of (exclusive) breastfeeding was defined as (exclusive) breastfeeding started within 48h post-delivery. In absence of an international standard, this definition appears a reasonable choice.

A paediatrician instructed mothers how to record in a calendar-diary the date of stopping breastfeeding and the date when liquids (water or water-based drinks, fruit juice, non-human milk or formula) or solid, semi-solid or soft foods were introduced, and the day at onset of any wheezing episode. An allergist trained mothers how to recognise wheezing. He/she explained the meaning of wheezing and the difference from other respiratory outcomes, particularly cold and noisy breathing. Thereafter, he/she showed sequentially the video of an infant with clinical diagnosis of wheezing and the videos of two non-wheezing infants having noisy breathing caused by mucus rattling or nasal congestion, respectively. The training process was previously validated in the hospital on 40 mothers. Accuracy in recognising wheezing was estimated at 91.9%, with sensitivity=91.2%, specificity=92.5%, positive predictive value=92.4, predictive negative value=91.4%. On day of hospital discharge a paediatrician consigned to mothers a brochure outlining the benefits of breastfeeding and invited them to contact the hospital if needed, and whenever the infant wheezed during lactation, to support mothers to continuing breastfeeding.

Calibrated personnel collected data by telephone on infant feeding practices and wheezing, at 30, 60, 90, 180, 270 and 360 days of age (±3 days).

For the analysis, the number of wheezing episodes was categorised as “no wheezing” (no wheezing episode) and “wheezing ever” (one or more episodes of wheezing). Wheezing ever was additionally split as “occasional wheezing” (one or two episodes) or “recurrent wheezing” (three or more episodes).8 The duration of breastfeeding was considered as both a continuous (days) and a categorical variable. Categories of exclusive breastfeeding duration were: infant never exclusively breastfed; ≤1 month (1–30 days), 1–4 months (31–120 days), 4–6 months (121–180 days), >6 months (>180 days). Categories of any breastfeeding duration were: infant never breastfed; ≤1 month (1–30 days), 1–4 months (31–120 days), 4–6 months (121–180 days), 6–9 months (181–270 days), >9 months (>270 days).

Statistical analysisThe sample size was determined to detect a difference of 50% or more in the incidence of wheezing at 12 months of age between exclusively breastfed and non-exclusively breastfed infants. Assuming an overall incidence rate of 34.4%9 at 12 months of age and an initiation rate of exclusive breastfeeding of 80%,29 with a type I error level of 0.05 and a power of 80% at least 149 non-exclusively breastfed infants would be required. Admitting a dropout of 10% at 12 months, 166 non-exclusively breastfed infants should be recruited, that is an overall sample of 830 mother–infant pairs.

Descriptive data are reported as mean and standard deviation (SD), median and Q1-Q3 interval, or number of observations and percentage. The Student's t-test, the Mann–Whitney U test or the chi-square test were used for univariate comparison and odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated on unconditional binary logistic model. Stepwise multivariate logistic regression models were then fitted (enter at P<0.10, remove at P>0.20) to assess the independent association of wheezing at 12 months of age with breastfeeding. A multivariate Cox's regression model [covariates deputed to enter were the same included in the logistic analysis] was fitted to assess the independent association of age at onset of the first wheezing episode with duration of breastfeeding. The statistical significance was posed at level P<0.05, and all the statistical tests are 2-tailed. The SPSS statistical package, version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., USA, Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) was used for the statistical analysis.

ResultsA total of 1606 mother–infant pairs participated in the study, with a retention rate of 100%, 98.6%, 97.9%, 96.5%, and 94.8% at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months, respectively. There was no difference between mother–infant pairs who dropped out of (n=84) or not (n=1522) the study, for any socio-demographic variable or medical history (minimum P=0.371). Of the mothers who dropped out, 18 had moved residence, 42 did not respond to three calls at daily intervals, seven had telephone unreachable, and 17 refused to be interviewed.

Breastfeeding ratesBreastfeeding started in 95.9% (1459/1522) of mother–infant pairs participating at 12 months and was exclusive in 86.1%. Breastfeeding was predominant in 1.3% of mother–infant pairs, while 8.4% of infants received both breast milk and formula. The rate of exclusive breastfeeding at age 30, 60, 90, 120 and 150 days was 61.2%, 55.0%, 52.6%, 47.0%, and 41.3%, respectively. No infant was exclusively breastfed for longer than 180 days. The rate of breastfeeding at age 30, 120, 180, 270 and 360 days was 86.6%, 73.8%, 58.4%, 37.7% and 26.3%, respectively. The median (Q1-Q3) duration of exclusive breastfeeding was 3.7 (0.7–5.6) months and of any breastfeeding was 6.6 (3.8–>12) months.

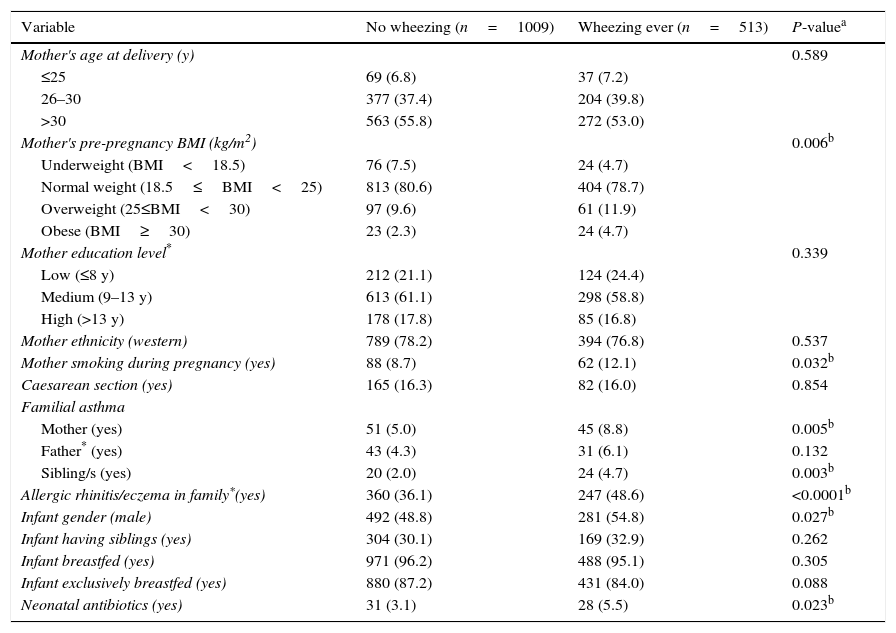

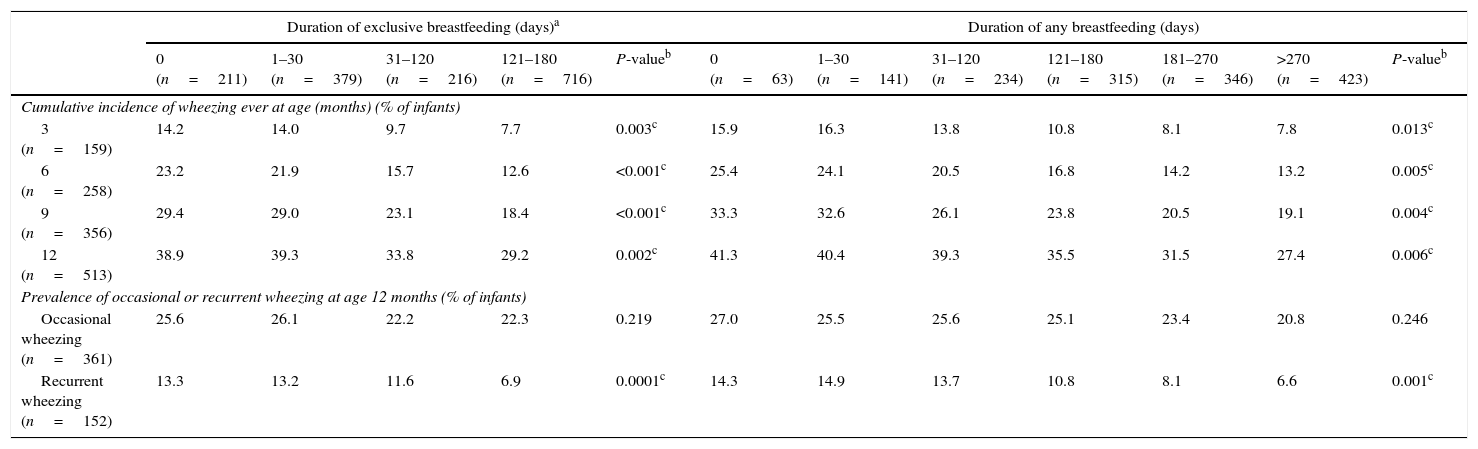

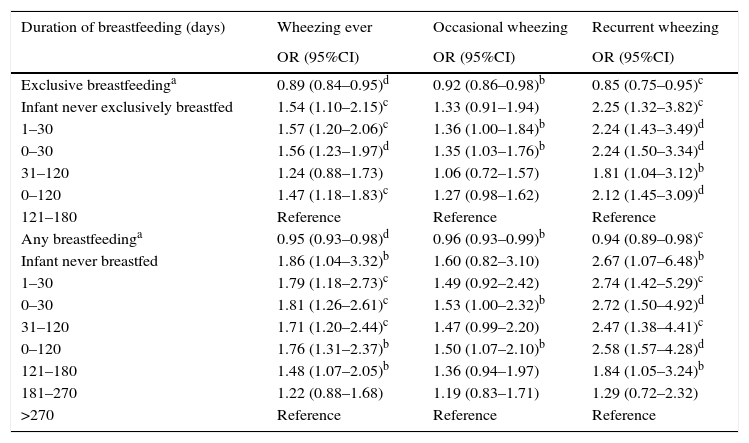

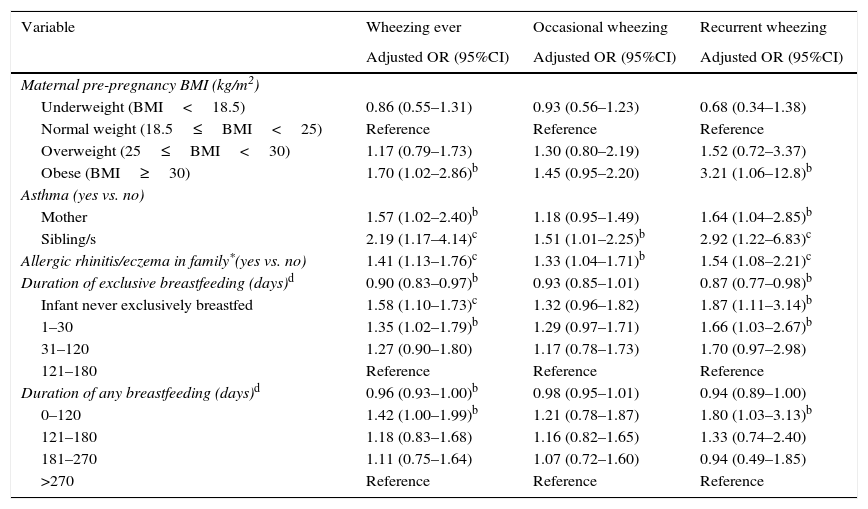

WheezingThe cumulative incidence of wheezing at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months of age was 10.4%, 16.9%, 23.4% and 33.7%, respectively. The rate of recurrent wheezing was 10.0%. Table 1 reports the socio-demographic characteristics and medical history of mother–infant pairs. Mothers of wheezing infants had pre-pregnancy BMI higher than those of non-wheezing infants (mean difference, 1.13; 95%CI, 0.82–1.44kg/m2), with higher risk of infant wheezing in obese than normal weight mothers (OR, 2.10; 95%CI, 1.13–3.91). An association was found of wheezing with maternal asthma (OR, 1.81; 95%CI 1.17–2.79), having sibling/s with asthma (OR, 2.43; 95%CI, 1.28–4.62), allergic rhinitis/eczema in family (OR, 1.67; 95%CI, 1.34–2.09), mother smoking during pregnancy (OR=1.46; 95%CI, 1.02–2.08), male gender (OR, 1.29; 95%CI, 1.03–1.60), neonatal antibiotics (OR, 1.82; 95%CI, 1.05–3.16). The mean (SD) birth body weight was 3358 (355) g and 3313 (364) g in wheezing and non-wheezing infants (P=0.022) and length was 50.2 (1.8) cm and 50.1 (1.7) cm (P=0.314), respectively. The mean (SD) duration of postpartum hospital stay was 2.6 (1.4) and 2.5 (1.4) days in wheezing and non-wheezing infants (P=0.969), respectively. The duration of exclusive breastfeeding and of any breastfeeding was shorter in infants with wheezing ever than no wheezing, with median 2.6 months vs. 4.1 months (P<0.001) and 5.7 months vs. 6.8 months (P=0.009), respectively. Table 2 reports the rate of wheezing by duration of breastfeeding. Table 3 reports the univariate ORs of wheezing at 12 months of age with breastfeeding. Longer duration of exclusive breastfeeding and of any breastfeeding was associated with reduced risk of wheezing. After adjustment for confounders (Table 4) each month of exclusive breastfeeding reduced the risk of wheezing ever by 11% and the risk of recurrent wheezing by 15% at 12 months of age. Infants non-exclusively breastfed or having exclusive breastfeeding stopped within one month had 58% and 35% higher risk of wheezing ever than infants exclusively breastfed for 4–6 months. Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity, maternal asthma, having sibling/s with asthma, and allergic rhinitis/eczema in family were also independently associated with wheezing ever.

Socio-demographic characteristics and medical history of mother–infants pairs in no wheezing and wheezing ever infants. Values are number (%) of observations.

| Variable | No wheezing (n=1009) | Wheezing ever (n=513) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother's age at delivery (y) | 0.589 | ||

| ≤25 | 69 (6.8) | 37 (7.2) | |

| 26–30 | 377 (37.4) | 204 (39.8) | |

| >30 | 563 (55.8) | 272 (53.0) | |

| Mother's pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 0.006b | ||

| Underweight (BMI<18.5) | 76 (7.5) | 24 (4.7) | |

| Normal weight (18.5≤BMI<25) | 813 (80.6) | 404 (78.7) | |

| Overweight (25≤BMI<30) | 97 (9.6) | 61 (11.9) | |

| Obese (BMI≥30) | 23 (2.3) | 24 (4.7) | |

| Mother education level* | 0.339 | ||

| Low (≤8 y) | 212 (21.1) | 124 (24.4) | |

| Medium (9–13 y) | 613 (61.1) | 298 (58.8) | |

| High (>13 y) | 178 (17.8) | 85 (16.8) | |

| Mother ethnicity (western) | 789 (78.2) | 394 (76.8) | 0.537 |

| Mother smoking during pregnancy (yes) | 88 (8.7) | 62 (12.1) | 0.032b |

| Caesarean section (yes) | 165 (16.3) | 82 (16.0) | 0.854 |

| Familial asthma | |||

| Mother (yes) | 51 (5.0) | 45 (8.8) | 0.005b |

| Father* (yes) | 43 (4.3) | 31 (6.1) | 0.132 |

| Sibling/s (yes) | 20 (2.0) | 24 (4.7) | 0.003b |

| Allergic rhinitis/eczema in family*(yes) | 360 (36.1) | 247 (48.6) | <0.0001b |

| Infant gender (male) | 492 (48.8) | 281 (54.8) | 0.027b |

| Infant having siblings (yes) | 304 (30.1) | 169 (32.9) | 0.262 |

| Infant breastfed (yes) | 971 (96.2) | 488 (95.1) | 0.305 |

| Infant exclusively breastfed (yes) | 880 (87.2) | 431 (84.0) | 0.088 |

| Neonatal antibiotics (yes) | 31 (3.1) | 28 (5.5) | 0.023b |

BMI=body mass index. Data related to mother–infant pairs participating at 12 months (n=1522).

Rates (%) of wheezing during the first 12 months of life by duration of exclusive breastfeeding and of any breastfeeding.

| Duration of exclusive breastfeeding (days)a | Duration of any breastfeeding (days) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (n=211) | 1–30 (n=379) | 31–120 (n=216) | 121–180 (n=716) | P-valueb | 0 (n=63) | 1–30 (n=141) | 31–120 (n=234) | 121–180 (n=315) | 181–270 (n=346) | >270 (n=423) | P-valueb | |

| Cumulative incidence of wheezing ever at age (months) (% of infants) | ||||||||||||

| 3 (n=159) | 14.2 | 14.0 | 9.7 | 7.7 | 0.003c | 15.9 | 16.3 | 13.8 | 10.8 | 8.1 | 7.8 | 0.013c |

| 6 (n=258) | 23.2 | 21.9 | 15.7 | 12.6 | <0.001c | 25.4 | 24.1 | 20.5 | 16.8 | 14.2 | 13.2 | 0.005c |

| 9 (n=356) | 29.4 | 29.0 | 23.1 | 18.4 | <0.001c | 33.3 | 32.6 | 26.1 | 23.8 | 20.5 | 19.1 | 0.004c |

| 12 (n=513) | 38.9 | 39.3 | 33.8 | 29.2 | 0.002c | 41.3 | 40.4 | 39.3 | 35.5 | 31.5 | 27.4 | 0.006c |

| Prevalence of occasional or recurrent wheezing at age 12 months (% of infants) | ||||||||||||

| Occasional wheezing (n=361) | 25.6 | 26.1 | 22.2 | 22.3 | 0.219 | 27.0 | 25.5 | 25.6 | 25.1 | 23.4 | 20.8 | 0.246 |

| Recurrent wheezing (n=152) | 13.3 | 13.2 | 11.6 | 6.9 | 0.0001c | 14.3 | 14.9 | 13.7 | 10.8 | 8.1 | 6.6 | 0.001c |

Data related to mother–infant pairs participating at 12 months (n=1522).

Univariate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of duration of exclusive breastfeeding and of any breastfeeding for wheezing ever, occasional wheezing, and recurrent wheezing at 12 months of age.

| Duration of breastfeeding (days) | Wheezing ever | Occasional wheezing | Recurrent wheezing |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | |

| Exclusive breastfeedinga | 0.89 (0.84–0.95)d | 0.92 (0.86–0.98)b | 0.85 (0.75–0.95)c |

| Infant never exclusively breastfed | 1.54 (1.10–2.15)c | 1.33 (0.91–1.94) | 2.25 (1.32–3.82)c |

| 1–30 | 1.57 (1.20–2.06)c | 1.36 (1.00–1.84)b | 2.24 (1.43–3.49)d |

| 0–30 | 1.56 (1.23–1.97)d | 1.35 (1.03–1.76)b | 2.24 (1.50–3.34)d |

| 31–120 | 1.24 (0.88–1.73) | 1.06 (0.72–1.57) | 1.81 (1.04–3.12)b |

| 0–120 | 1.47 (1.18–1.83)c | 1.27 (0.98–1.62) | 2.12 (1.45–3.09)d |

| 121–180 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Any breastfeedinga | 0.95 (0.93–0.98)d | 0.96 (0.93–0.99)b | 0.94 (0.89–0.98)c |

| Infant never breastfed | 1.86 (1.04–3.32)b | 1.60 (0.82–3.10) | 2.67 (1.07–6.48)b |

| 1–30 | 1.79 (1.18–2.73)c | 1.49 (0.92–2.42) | 2.74 (1.42–5.29)c |

| 0–30 | 1.81 (1.26–2.61)c | 1.53 (1.00–2.32)b | 2.72 (1.50–4.92)d |

| 31–120 | 1.71 (1.20–2.44)c | 1.47 (0.99–2.20) | 2.47 (1.38–4.41)c |

| 0–120 | 1.76 (1.31–2.37)b | 1.50 (1.07–2.10)b | 2.58 (1.57–4.28)d |

| 121–180 | 1.48 (1.07–2.05)b | 1.36 (0.94–1.97) | 1.84 (1.05–3.24)b |

| 181–270 | 1.22 (0.88–1.68) | 1.19 (0.83–1.71) | 1.29 (0.72–2.32) |

| >270 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

Data related to mother–infant pairs participating at 12 months (n=1522).

Variables independently associated with wheezing ever, occasional wheezing and recurrent wheezing at 12 months of age. Multivariate logistic regression analysis.a

| Variable | Wheezing ever | Occasional wheezing | Recurrent wheezing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95%CI) | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | |

| Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Underweight (BMI<18.5) | 0.86 (0.55–1.31) | 0.93 (0.56–1.23) | 0.68 (0.34–1.38) |

| Normal weight (18.5≤BMI<25) | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Overweight (25≤BMI<30) | 1.17 (0.79–1.73) | 1.30 (0.80–2.19) | 1.52 (0.72–3.37) |

| Obese (BMI≥30) | 1.70 (1.02–2.86)b | 1.45 (0.95–2.20) | 3.21 (1.06–12.8)b |

| Asthma (yes vs. no) | |||

| Mother | 1.57 (1.02–2.40)b | 1.18 (0.95–1.49) | 1.64 (1.04–2.85)b |

| Sibling/s | 2.19 (1.17–4.14)c | 1.51 (1.01–2.25)b | 2.92 (1.22–6.83)c |

| Allergic rhinitis/eczema in family*(yes vs. no) | 1.41 (1.13–1.76)c | 1.33 (1.04–1.71)b | 1.54 (1.08–2.21)c |

| Duration of exclusive breastfeeding (days)d | 0.90 (0.83–0.97)b | 0.93 (0.85–1.01) | 0.87 (0.77–0.98)b |

| Infant never exclusively breastfed | 1.58 (1.10–1.73)c | 1.32 (0.96–1.82) | 1.87 (1.11–3.14)b |

| 1–30 | 1.35 (1.02–1.79)b | 1.29 (0.97–1.71) | 1.66 (1.03–2.67)b |

| 31–120 | 1.27 (0.90–1.80) | 1.17 (0.78–1.73) | 1.70 (0.97–2.98) |

| 121–180 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Duration of any breastfeeding (days)d | 0.96 (0.93–1.00)b | 0.98 (0.95–1.01) | 0.94 (0.89–1.00) |

| 0–120 | 1.42 (1.00–1.99)b | 1.21 (0.78–1.87) | 1.80 (1.03–3.13)b |

| 121–180 | 1.18 (0.83–1.68) | 1.16 (0.82–1.65) | 1.33 (0.74–2.40) |

| 181–270 | 1.11 (0.75–1.64) | 1.07 (0.72–1.60) | 0.94 (0.49–1.85) |

| >270 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

BMI=body mass index. Data related to mother–infant pairs participating at 12 months (n=1522). Adjusted ORs compare infants in the wheezing ever, occasional wheezing, or recurrent wheezing group to infants with no wheezing.

Missing values: Allergic rhinitis/eczema in family=17. Number of subjects included in the final model was 1505 for wheezing ever, 1357 for occasional wheezing, 1148 for recurrent wheezing.

Covariates deputed to enter into models: maternal age at delivery(<30/≥30 y), maternal pre-pregnancy BMI (underweight/normal weight/overweight/obese), maternal education level (low/medium/high), maternal ethnicity (western/non-western) maternal smoking during pregnancy (yes/no), caesarean section (yes/no), infant's gender (male/female), infants’ birth weight (<3393 [median]/≥3393g) infant's length (<50.1 [median]/≥50.1cm), having siblings (yes/no), maternal asthma (yes/no), paternal asthma (yes/no), sibling/s with asthma (yes/no), allergic rhinitis/eczema in family (yes/no), neonatal antibiotics (yes/no). Duration of exclusive and any breastfeeding was forced to enter into models.

The mean (SD) age at onset of the first wheezing episode was 5.3 (3.1) months, median (Q1–Q3) 5.5 (2.5–9.2) months. At univariate analysis longer duration of exclusive breastfeeding (P=0.006; log-rank test) and of any breastfeeding (P=0.023) was associated with later age at onset of wheezing. At multivariate Cox's regression analysis, the association remained significant for duration of exclusive breastfeeding (P=0.038) but not for duration of any breastfeeding (P=0.277). Compared to infants exclusively breastfed for 4–6 months those non-exclusively breastfed or having exclusive breastfeeding stopped within one month had higher risk of earlier onset of wheezing, with an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) (95%CI) of 1.22 (1.02–1.52) and 1.19 (1.02–1.47), respectively. The other variables independently associated with earlier onset of wheezing were having sibling/s with asthma (adjusted HR, 2.82; 95%CI, 1.77–4.48) and allergic rhinitis/eczema in family (1.44; 1.77–4.48). The association with maternal asthma (1.20; 0.92–1.56), maternal pre-pregnancy BMI (obesity vs. normal weight: 1.65; 95%CI, 0.89–3.06) and neonatal antibiotic (1.50; 0.84–2.67) did not reach statistical significance.

Eighty-five (16.3%) of 513 wheezing infants had the first wheezing episode during lactation, 23 during exclusive breastfeeding and 62 during any breastfeeding. In no case was exclusive or any breastfeeding stopped. A secondary analysis, performed excluding infants who had the first wheezing episode during lactation, showed an independent positive association of the duration of exclusive breastfeeding with age at onset of wheezing (P=0.029). Compared to infants exclusively breastfed for 4–6 months those non-exclusively breastfed or having exclusive breastfeeding stopped within one month had an adjusted HR (95%CI) of 1.29 (1.03–1.62) and 1.26 (1.01–1.58), respectively.

DiscussionThis study investigated whether the duration of exclusive breastfeeding may reduce the risk of wheezing at 12 months of age and is associated with later age at onset of wheezing.

The study included a series of mother–infant pairs recruited at a hospital in Milan where the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative30 has been implemented since 2010. By recruiting in a single hospital reduced potential biases due to the different breastfeeding practices in Lombardy.29 This study overcomes many of the methodological limitations of previous research. Strengths of the study were the prospective design combined with high statistical power, clear eligibility criteria, accurate international standard definitions and continuous measurement of infant feeding practices. Exclusive breastfeeding was defined in accordance with the WHO28 and wheezing with the International Classification of Diseases.27 The longitudinal collection of data, also using a home calendar-diary, provided accurate information on breastfeeding and age at wheezing. Results were acceptably adjusted for confounders. Lastly, there was a very good retention rate at 12 months. The American Academy of Pediatrics2 and other Authors3,5,19 have underlined the importance of collecting quality prospective data to overcome the major methodological issues raised in the literature.2,6 In particular, continuous measurement of breastfeeding duration,2,6 together with accurate definition and distinguishing between “any” or “exclusive” breastfeeding2 have been recommended.

The rate of exclusive breastfeeding was higher than the mean rates in Lombardy29 and within the upper quartile of the developed countries.31 The incidence of wheezing ever at three months (10%) and at 12 months (33.7%) of age was within the range of the European estimates (mean 10.5% at three months and 34.4% at 12 months), as reported in the EISL study,9 while the rate of recurrent wheezing (10%) was lower than the European mean of 15%.9 Lower rates at 12 months of age have been found in Sweden (20.2% for wheezing ever and 5.3% for recurrent wheezing).14 Interestingly, it should be noted that among developed countries Sweden (60% of exclusive breastfeeding at four months and 72% of breastfeeding at six months) and Norway (70% of exclusive breastfeeding at three months and 80% of breastfeeding at six months) have the best breastfeeding policy with the highest rates of breastfeeding.31 The incidence rate of wheezing has been estimated of 39.3% in New Zealand at 15 months4 and of 34% at 12 months of age in the USA.32 Higher rates of wheezing have been found in Latin America with a mean of 47% for wheezing ever and of 22% for recurrent wheezing at 12 months of age.9

In a prospective study using accurate definitions of infant breastfeeding and continuous measurement of exclusive breastfeeding, Silvers et al.4 found that, after adjusting for confounders, each month of exclusive breastfeeding would reduce wheezing ever by about 12%, that is comparable with the value of 11% estimated in this study. Other studies20–25 found an independent association of longer duration of exclusive breastfeeding with a reduced occurrence of wheezing at 1220,22–25 and 1821 months of age. For example, Bercedo-Sanz et al.25 estimated an odds ratio of 1.47 for wheezing ever and of 1.53 for recurrent wheezing in infants exclusively breastfed for shorter than three months. On the contrary, a prospective cohort Japanese study,33 found that neither exclusive breastfeeding for four months or longer nor breastfeeding for six months or longer were associated to the risk of wheezing. However, it should be noted that some studies used unclear definitions and not distinguished between exclusive or any breastfeeding and/or reported breastfeeding duration on a categorised scale.20–25,33

Longer duration of any breastfeeding has also been associated with a reduced risk of wheezing at 12 months of age, after adjustment for confounders.4,6,13–16 For example, Alm et al.14 estimated in infants breastfed for 0–4 months an adjusted odds ratio for wheezing ever of 1.3, as compared to infants breastfed for nine months or longer. Bozaykut et al.16 found that duration of breastfeeding shorter than six months increases the risk of recurrent wheezing. A Brazilian study34 found a relationship of breastfeeding with wheezing ever and recurrent wheezing at 12 months of age at univariate analysis only. In a cross-sectional Dutch study, the duration of breastfeeding categorised at six months was not associated with the risk of wheezing at 12 months of age.35 Similarly to Silvers et al.,4 in the present study any breastfeeding had a lesser role than exclusive breastfeeding in reducing the risk of wheezing.

There is a lack of studies investigating about the age at the onset of wheezing and breastfeeding. In this study, age at the onset of wheezing was associated positively with duration of exclusive breastfeeding, also after adjustment for confounders, with infants not exclusively breastfed or exclusively breastfed for less than one month having about 20% higher risk of earlier onset of wheezing than infants exclusively breastfed for 4–6 months. No association was found with any breastfeeding. In a recent publication from the EISL study36 exclusive breastfeeding for longer than three months was associated with later age at the first wheezing episode in Latin-American but not in European infants. However, it should be noted that in this study36 duration of breastfeeding was dichotomised. Anyway, the above results strengthen once more the relevance of exclusive breastfeeding during the first months of life.

In accordance with the literature (e.g.14–16,20,21,23–25,33–35), wheezing was independently associated with some inherent risk factors, namely maternal asthma, allergic rhinitis/eczema in family and having siblings with asthma. Association with maternal obesity was significant as also found by other authors [e.g.,24]. In accordance with other studies, maternal smoking during pregnancy,14 male gender,14,35 and neonatal antibiotics35 were associated with increased risk of wheezing at univariate analysis only. An independent association of wheezing with infant's gender has been found in some studies.14,24 Alm et al.14 reported that use of antibiotics in the neonatal period was an independent risk factor for wheezing at 12 months of age but it should be noted that their study included also preterm neonates and neonates having birth weight less than 2500g.

LimitationsThis study has some limitations that need to be explicitly addressed. Firstly, wheezing was not confirmed by clinical examination. However, mothers had been well-trained to recognise wheezing, and accuracy of the training recognising process was of 92%. Therefore, although a recognition bias cannot be excluded, it was reasonably reduced. Another limitation is that no data were collected on potential environmental confounders, such as damp housing/mould and air pollution. In one study, damp housing was associated with increased risk of wheezing in the first year of life.35 A systematic review conducted in 2011 suggested that exposure to mould would be associated with wheezing.37 Recent studies have found significant effects of domestic PM2.538 and traffic-related air pollution in triggering wheezing in infants aged 0–1 year.39 In this study data on air pollution were not collected due to financial constraints. However, the risk of exposure to traffic-related air pollution was reasonably uniform as participants lived in a restricted urban area (<15km distance to hospital) and in this area air pollution was similar in 2013 and 2014.40 Lastly, although a risk of confounding due to reverse causation may be not excluded it would be reduced as mothers were actively promoted for continuing breastfeeding also after the onset of wheezing. Really, both exclusive breastfeeding and any breastfeeding were continued in all infants after the first wheezing episode. Moreover, excluding from the statistical analyses infants who wheezed during lactation, longer duration of exclusive breastfeeding remained associated with later age at onset of wheezing. This suggests that a longer duration of exclusive breastfeeding could play a protective role on early wheezing, as suggested by other authors.4 Lastly, no aetiological conclusion can be drawn here but inherent practical and ethical issues would preclude prospective randomised trials of different feeding regimes, as pointed out by the American Academy of Paediatrics.2

In conclusion, results of this study support that a longer duration of breastfeeding is associated with a reduced risk of wheezing during the first 12 months of life, and make strongly evident that exclusive breastfeeding is especially important. As wheezing is the most common symptom associated with asthma in young children, robust promotion of prolonged duration of exclusive breastfeeding may be a simple and inexpensive intervention to reduce the risk of early wheezing.

Authors’ contributionsGiuseppe Banderali organised and monitored the data collection, and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Carlotta Lassandro contributed in coordinating the data collection and in writing the manuscript.

Diego Peroni participated in the development of the protocol and analytical framework for the study, and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Giovanni Radaelli supervised the design, protocol and execution of the study, performed the data analyses, contributed to the writing of the manuscript and supervised the final version.

Elvira Verduci had primary responsibility for design of the study, and contributed to writing the manuscript.

All authors gave final approval of the version to be submitted.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Protection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.