To describe results of double-blind placebo-controlled food challenges (DBPCFC) with cow's milk, hen's egg, soy, peanut and hazelnut in general paediatric practice.

MethodsFood challenges were performed between January 2006 and June 2011, in children 0–18 years of age, on two half-day hospital admissions with a one-week interval. Tests were performed in a double-blind fashion following a standardised protocol with validated recipes.

ResultsOverall, 234 food challenges were performed in 209 children: 160 with cow's milk, 35 with peanut, 21 with hen's egg, 11 with hazelnuts, and 7 with soy. In two thirds of the cases, the DBPCFC was negative (cow's milk: 57.5%; peanut: 40.0%; hen's egg: 66.7%, hazelnut: 90.9%, soy: 100%). The only patient characteristic significantly associated with a positive DBPCFC was the presence of symptoms from three different organ systems (p=0.007). Serious systemic allergic reactions with wheeze or anaphylaxis occurred in only two children (0.9%). Symptoms were recorded on 29.3% of placebo days. In 30/137 children with a negative test (22%), symptoms returned when reintroducing the allergen into the diet, mostly (66.7%) transient. Of the 85 tests regarded as positive by the attending physician, 19 (22.4%) did not meet predefined criteria for a positive test. This was particularly common with non-specific symptoms.

ConclusionA DBPCFC can be safely performed in a general hospital for a range of food allergens. The test result is negative in most cases except for peanut. Non-specific symptoms may hamper the interpretation of the DBPCFC, increasing the risk of a false-positive result.

The cumulative prevalence of food allergy in children is estimated at 1–5%.1–3 Because of its non-specific symptoms, making or refuting the diagnosis of food allergy in children is difficult. Symptoms of food allergy may come from different organ systems (skin, gastrointestinal, respiratory or general symptoms) and may vary in severity from mild to life threatening.1,4,5 History is a key diagnostic tool because food allergy usually produces similar symptoms every time the child is exposed to the allergen, whilst these symptoms completely disappear when exposure is avoided.4 However, history per se is unreliable because approximately 20–25% of parents are under the impression that their child is allergic to food based on symptoms observed after exposure to certain foods.2–4 The usefulness of establishing sensitisation to foods (skin prick test or assessment of specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) in blood) is debated, primarily because of the poor specificity of these tests, with more than half of sensitised individuals being tolerant to the food.4,6

The disadvantages of an incorrect food allergy diagnosis include social isolation of the child, nutrient deficiency, growth stunting, and insufficient attention to the true underlying cause of the symptoms.4,7–9 This highlights the importance of careful diagnosis of food allergy in children. The double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC) is universally accepted as the gold standard of food allergy diagnosis,4,10 because of the high probability of false-positive results of open food challenges.4,11 The main disadvantage of the DBPCFC is that it is labour-intensive, time-consuming, and as a result, expensive.

We present the results of DBPCFCs to a range of allergens performed in a general paediatric practice over a five-year period. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of DBPCFC results in a general paediatric practice, the setting in which most cases of (suspected) food allergy are being evaluated.

Patients and methodsThe present study was carried out at the Princess Amalia Children's Clinic in the Isala klinieken, a large general teaching hospital in Zwolle, the Netherlands. At the time of the study, the DBPCFC was the recommended procedure to diagnose food allergy, also for children with symptoms suggestive of anaphylaxis to foods. Children were not preselected based on results of food sensitisation tests (skin prick tests or specific IgE levels). All children with suspected food allergy whose parents consented to DBPCFC were therefore included in the study.

For the purpose of this study, we reviewed and analysed the results of all DBPCFCs with cow's milk, hen's egg, soy, peanut or hazelnut carried out between January 2006 and June 2011, in children 0–18 years of age.

DBPCFCs were carried out following a standardised protocol consisting of two challenge half-days (placebo and verum (active ingredient), in random order), one week apart. Each challenge day began with a low dose, increasing in six steps with 20min intervals up to a cumulative dose of food allergen that would elicit a reaction in those allergic to the food.12 Patients remained in hospital until 1.5h after the last challenge dose. We used validated recipes of food allergens hidden in regular foodstuffs (e.g., pancakes, cookies) in which placebo and verum test foods were identical in taste, scent, and colour.12 If children refused to eat more than half of the total dose, without a manifest clinical response to the food, the challenge was considered a failure, and results were not analysed.

Each food challenge was supervised by a single trained observer (experienced paediatric nurses who completed dedicated training in recognising and managing symptoms of allergy including anaphylaxis), who carefully recorded each symptom or sign that the child presented on a case record form. A consultant paediatrician was available for immediate consultation and treatment if required at all times. The patient, parents, supervising nursing staff, and attending paediatrician were all blinded to the key of the test, and were therefore unaware whether the child was being exposed to verum or placebo. When objective symptoms occurred (erythema, urticaria, angio-oedema, inspiratory stridor, wheezing, or vomiting), the challenge was stopped, and medication was provided if needed (oral nonsedating antihistamine, salbutamol by metered dose inhaler/spacer combination, or epinephrine intramuscularly). In the case of subjective symptoms (crying, agitation, abdominal pain, mouth tingling), the last given dose was repeated. If symptoms persisted upon repetition of the dose associated with the symptoms, the challenge was stopped. If symptoms disappeared, the challenge was continued. Parents were asked to record symptoms at home after each challenge day to identify late allergic reactions, if any.

The DBPCFC key disclosing which of the two challenge days was placebo and which was verum was not to be opened until a scheduled follow-up visit of the patient one week after the second challenge day.

According to the clinic's DBPCFC protocol, a challenge was to be regarded as positive, confirming the diagnosis of food allergy, when symptoms had occurred on the verum day and had been absent on the placebo day, provided that these symptoms were either identical to the symptoms presented in the history upon which food allergy has been suspected, or were objective and unmistakably allergic.13 In all other cases, the diagnosis of ‘food allergy’ was to be rejected.

Data on symptoms occurring during the DBPCFC and additional clinical characteristics were retrieved from the hospital chart. Data were analysed with SPSS 17.0, using t tests to compare means and chi-squared test to compare proportions.

Medical ethics review was waived because under Dutch law this is not required for a retrospective chart review study.

ResultsPopulationA total of 275 DBPCFCs were analysed, 37 of which were considered failures because of insufficient food intake, and four could not be analysed due to a lack of information in the chart. A total of 234 completed DBPCFCs were analysed (149 in boys; median age: 22 months; 69% below four years of age). In 12 cases, the attending paediatrician evaluating the result of the DBPCFC recorded in the chart that the symptom pattern occurring on verum and placebo days was insufficiently clear to allow making or refuting the diagnosis of food allergy. These 12 food challenges were excluded from further analysis. Overall, we analysed 222 DBPCFCs in 200 children (125 boys, 75 girls). Of these 200 children, 106 (53.0%) had a personal history of atopic disease (eczema, asthma, allergic rhinitis), and a positive family history of atopic disease was found in 131 children (65.5%). In most children (90%), only a single DBPCFC was performed. Eighteen children (9%) had two DBPCFCs, and two children (1%) had three.

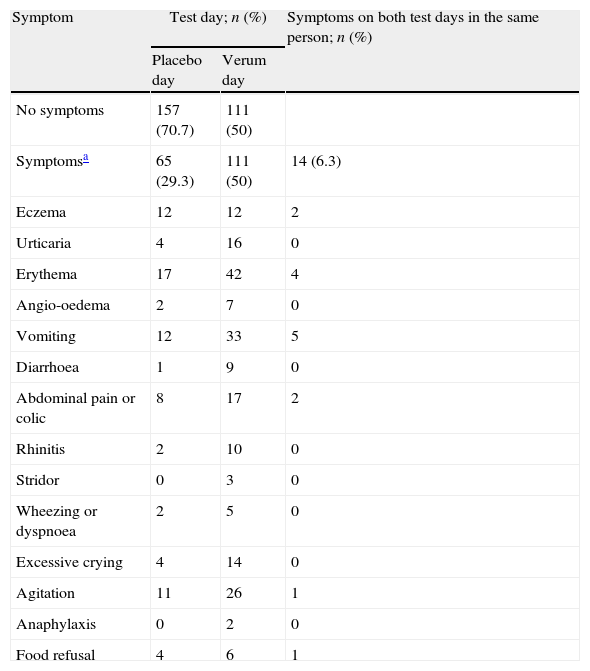

Symptoms during DBPCFCSymptoms were recorded on 111 (50%) verum and 65 (29.3%) placebo days (p<0.001, Table 1). Thirty-four children (15.3%) experienced symptoms on both test days, 14 of whom (6.3% of all children) displayed the same symptoms on verum and placebo days. In 80 children (36.0%), no symptoms occurred on either test day. Severe symptoms during DBPCFC were rare. Only two cases (0.9%) required medication other than an antihistamine: one 11-yr old boy with a history of asthma required salbutamol by inhalation for wheeze during a cow's milk challenge; and one 4-yr old girl with a history of anaphylaxis after eating a cookie developed an anaphylactic reaction during peanut challenge, and was treated with epinephrine intramuscularly and with salbutamol by inhalation. Both recovered quickly.

Recorded symptoms during 222 DBPCFCs in children.

| Symptom | Test day; n (%) | Symptoms on both test days in the same person; n (%) | |

| Placebo day | Verum day | ||

| No symptoms | 157 (70.7) | 111 (50) | |

| Symptomsa | 65 (29.3) | 111 (50) | 14 (6.3) |

| Eczema | 12 | 12 | 2 |

| Urticaria | 4 | 16 | 0 |

| Erythema | 17 | 42 | 4 |

| Angio-oedema | 2 | 7 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 12 | 33 | 5 |

| Diarrhoea | 1 | 9 | 0 |

| Abdominal pain or colic | 8 | 17 | 2 |

| Rhinitis | 2 | 10 | 0 |

| Stridor | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Wheezing or dyspnoea | 2 | 5 | 0 |

| Excessive crying | 4 | 14 | 0 |

| Agitation | 11 | 26 | 1 |

| Anaphylaxis | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Food refusal | 4 | 6 | 1 |

Almost all children had multiple symptoms during the challenge. Only one child had exactly the same symptoms during the challenge as those reported in the original history upon which food allergy was suspected. Partial agreement with history symptoms was found for most of the symptoms on the placebo day (38; 58.5%) and the verum day (72; 64.9%).

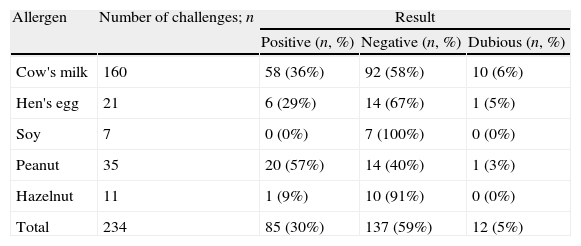

Results of DBPCFCThe results of the DBPCFC for all food allergens tested are presented in Table 2. Most DBPCFCs were negative, except for peanut (p=0.007, Table 2). There was no relationship between a positive DBPCFC and age, gender, personal or family history of atopic disease, or nature of symptoms (all p-values >0.3, Table 3). Children with symptoms of three or more organ systems in the original history were more likely to have a positive DBPCFC (38/75, 50.7%) than those with symptoms of one or two systems (47/147, 32.0%, p=0.007).

Results of double-blind placebo-controlled food challenges in children, per allergen.

| Allergen | Number of challenges; n | Result | ||

| Positive (n, %) | Negative (n, %) | Dubious (n, %) | ||

| Cow's milk | 160 | 58 (36%) | 92 (58%) | 10 (6%) |

| Hen's egg | 21 | 6 (29%) | 14 (67%) | 1 (5%) |

| Soy | 7 | 0 (0%) | 7 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Peanut | 35 | 20 (57%) | 14 (40%) | 1 (3%) |

| Hazelnut | 11 | 1 (9%) | 10 (91%) | 0 (0%) |

| Total | 234 | 85 (30%) | 137 (59%) | 12 (5%) |

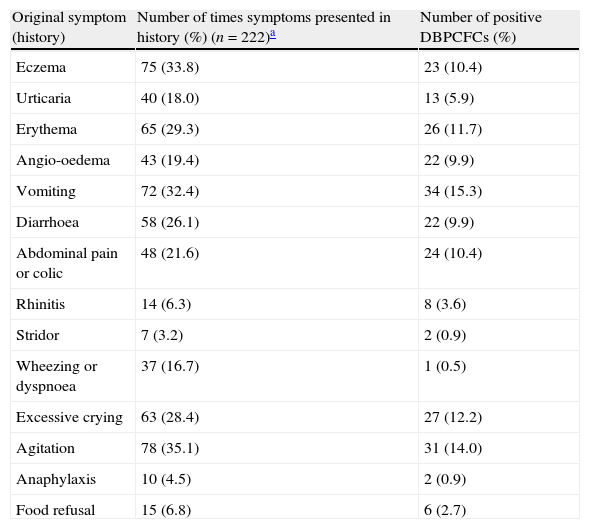

Relationship between symptoms of food allergy obtained in original history and the result of double-blind placebo-controlled food challenges.

| Original symptom (history) | Number of times symptoms presented in history (%) (n=222)a | Number of positive DBPCFCs (%) |

| Eczema | 75 (33.8) | 23 (10.4) |

| Urticaria | 40 (18.0) | 13 (5.9) |

| Erythema | 65 (29.3) | 26 (11.7) |

| Angio-oedema | 43 (19.4) | 22 (9.9) |

| Vomiting | 72 (32.4) | 34 (15.3) |

| Diarrhoea | 58 (26.1) | 22 (9.9) |

| Abdominal pain or colic | 48 (21.6) | 24 (10.4) |

| Rhinitis | 14 (6.3) | 8 (3.6) |

| Stridor | 7 (3.2) | 2 (0.9) |

| Wheezing or dyspnoea | 37 (16.7) | 1 (0.5) |

| Excessive crying | 63 (28.4) | 27 (12.2) |

| Agitation | 78 (35.1) | 31 (14.0) |

| Anaphylaxis | 10 (4.5) | 2 (0.9) |

| Food refusal | 15 (6.8) | 6 (2.7) |

DBPCFC: double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge.

After each of the 137 negative tests, reintroduction of the tested allergen was recommended. Five parents refused this because they did not agree that the test result was negative. In 30 children (21.9%), mild non-specific symptoms occurred during reintroduction of the allergen into the diet. In most children (n=20) these symptoms were transient during persistent exposure to the food, but in the remaining 10 cases, these symptoms prompted the parents to avoid the food once again from their child's diet. There was no significant relationship between clinical characteristics (age, gender, symptoms, personal or family history of atopic disease, nature of the allergen) and the success of reintroduction after a negative challenge (all p values >0.1). These renewed symptoms occurred too late and were too non-specific to be interpreted as late allergic reactions to the food challenge.

False-positivesOf the 85 tests interpreted as positive by the physician who reviewed the challenge test results one week after the second test day when the child was seen in clinic, 19 challenges (22.4%) were not confirmed as positive when the two authors strictly applied the predefined criteria for a positive test put down in the DBPCFC protocol. In five of these children, symptoms had occurred during the food challenge which, in retrospect, could be attributed to an intercurrent respiratory or gastrointestinal viral infection. Eight children had similar symptoms on placebo and verum days, and six had an insufficient match between subjective symptoms on verum day and the original symptoms in the history. In all false-positive cases, children had displayed multiple symptoms on placebo and verum days, the majority of which were subjective symptoms.

DiscussionThis study shows that DBPCFCs to a range of foods can be safely conducted in a general paediatric practice, if basic conditions for quality and safety are being met. In agreement with previous studies, most DBPCFCs were negative,11,14 and reintroducing the suspected allergen into the diet succeeded in most cases. However, it proved difficult to strictly apply predefined criteria for a positive test, in particular when children displayed multiple subjective symptoms, and this contributed to false-positive DBPCFCs. Careful standardisation and monitoring of the DBPCFCs is therefore needed to successfully apply the test in actual practice.

Despite the large number of patients studied (n=222), no patient characteristics significantly predicted a positive DBPCFC. Although a positive DBPCFC was more likely when symptoms from multiple organ systems were recorded, the predictive value of this characteristic was insufficient to be practically useful. Consequently, food allergy can neither be rejected nor confirmed on the basis of the nature of symptoms alone,15 and the DBPCFC remains the gold standard for diagnosing food allergy.

The low risk of severe allergic reactions during DBPCFC in our study is in accordance with previous findings.5,16 This illustrates the safety of DBPCFC; anaphylaxis symptoms during DBPCFC are rare, and can be treated by properly trained staff.

Renewed symptoms after reintroduction of the allergen into the child's diet following a negative DBPCFC was more common in the present study (42.9%) than in prior research (maximum 3%).13,16 This does not necessarily indicate a false-negative test result, because these symptoms were transient in the majority of patients (20/30, 66.7%), eventually allowing successful reintroduction of the allergen into the child's diet. If parents report reoccurrence of symptoms after reintroducing a previously avoided food allergen into the child's diet following a negative DBPCFC, we recommend to explore the exact nature and time pattern of symptoms in relation to food exposure in detail, to check whether these symptoms are objective and reproducible upon each exposure. In most cases this helps to convince parents that the food can be ingested safely and without symptoms. Some parents, however, continue to interpret minor non-specific symptoms when reintroducing the food as evidence of food allergy, even though the attending physician does not. In our study, reintroducing of the tested allergen after a negative challenge failed in approximately 10% of cases.

Pitfalls in interpretationWhilst it is obvious that non-specific symptoms on the placebo day are coincidental, the same symptom on the verum day may be judged as an expression of food allergy. It is likely that this contributes to false-positive test results. Similar to an open food challenge, physician preoccupation may play a role in this process,11 in particular when the clinician unlocks the challenge key before interpreting the symptoms on both test days. We believe this may have played a role in explaining the unexpectedly high prevalence of DBPCFCs incorrectly classified as positive. To the best of our knowledge, this pitfall in the interpretation of the DBPCFC has not been reported previously. When evaluating a DBPCFC result, we therefore recommend to interpret the symptoms on each test day first, and then to open the challenge key.

A second potential pitfall has to do with the broad spectrum of symptoms of food allergy. This may cause ambiguity in judging whether subjective symptoms during DBPCFC sufficiently match the original symptoms.13 Almost all children had multiple symptoms in the original history, one or more of which usually occur on one or two test days (Table 3). Complete agreement between symptoms during challenge and those obtained in original history was rare, however. The clinician interpreting the test result then has to decide whether there is enough agreement between symptoms during challenge and those in original history, and determines if this should be seen as a reaction. Our results show that physicians may differ in their interpretation of this agreement between symptoms during DBPCFC and symptoms from the original history. Although this is particularly likely to cause bias when subjective symptoms are concerned, we also noted that objective symptoms may sometimes be difficult to interpret, for example when the chart notes reported that the child had “mild diarrhoea” or “threw up a mouthful”. Even the DBPCFC, the gold standard of food allergy diagnosis, is apparently not free from pitfalls in its interpretation. Careful further research about the impact of these pitfalls on the diagnostic validity of the DBPCFC is needed. Although repeating DBPCFCs may help to reduce the number of challenges with an inconclusive result, this is hardly feasible in clinical practice.

The main strengths of our study include the relevant general paediatric setting, in which most of the cases of suspected food allergy are being evaluated, and the identification of potential pitfalls in the evaluation of DBPCFC results, particularly when dealing with vague and non-specific symptoms. The primary limitations are the retrospective nature relying on chart notes which were not always complete, and the relatively small number of DBPCFCs to other allergens than cow's milk. Generalising our results to other settings should be performed cautiously, therefore.

ConclusionThe results of our study suggest that DBPCFCs can be safely performed in general paediatric practice for a range of food allergens. The test result is negative in most cases, except, in this cohort, for peanut. Physicians interpreting results of DBPCFCs should be aware that recording mild and non-specific symptoms may hamper the interpretation of the DBPCFC and contribute to false-positive test results.

Ethical disclosuresPatients’ data protectionConfidentiality of Data. The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.