The diagnosis of anaphylactic reactions due to opiates during anaesthesia can be difficult, since in most cases various drugs may have been administered. Detection of specific IgE to poppy seed might be a marker for sensitisation to opiates in allergic people and heroin-abusers. This study assessed the clinical value of morphine, pholcodine and poppy seed skin-prick and IgE determination in people suffering hypersensitivity reactions during anaesthesia or analgesia and drug-abusers with allergic symptoms.

MethodsWe selected heroin abusers and patients who suffered severe reactions during anaesthesia and analgesia from a database of 23,873 patients. The diagnostic yield (sensitivity, specificity and predictive value) of prick and IgE tests in determining opiate allergy was analysed.

ResultsOverall, 149 patients and 200 controls, mean age 32.9±14.7 years, were included. All patients with positive prick to opiates showed positive prick and IgE to poppy seeds, but not to morphine or pholcodine IgE. Among drug-abusers, 13/42 patients (31%) presented opium hypersensitivity confirmed by challenge tests. Among non-drug abusers, sensitisation to opiates was higher in people allergic to tobacco (25%), P<.001. Prick tests and IgE against poppy seed had a good sensitivity (95.6% and 82.6%, respectively) and specificity (98.5% and 100%, respectively) in the diagnosis of opiate allergy.

ConclusionsOpiates may be significant allergens. Drug-abusers and people sensitised to tobacco are at risk. Both the prick and specific IgE tests efficiently detected sensitisation to opiates. The highest levels were related to more-severe clinical profiles.

It is estimated that 60% of all hypersensitivity reactions during anaesthesia are IgE-mediated and that neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBA), also called muscle relaxants, are responsible for 60% of these reactions.1 Anaphylactic reactions to NMBA tend to be severe and often life-threatening, with approximately 80% of reactions reported to be grade III or IV.2

The diagnosis of anaphylactic reactions during anaesthesia can be difficult, since in most cases various drugs have been administered. Follow-up investigation is therefore necessary to prevent potential life-threatening re-exposure to the offending drug.

NMBA are mainly administered intravenously but may also be given intramuscularly.

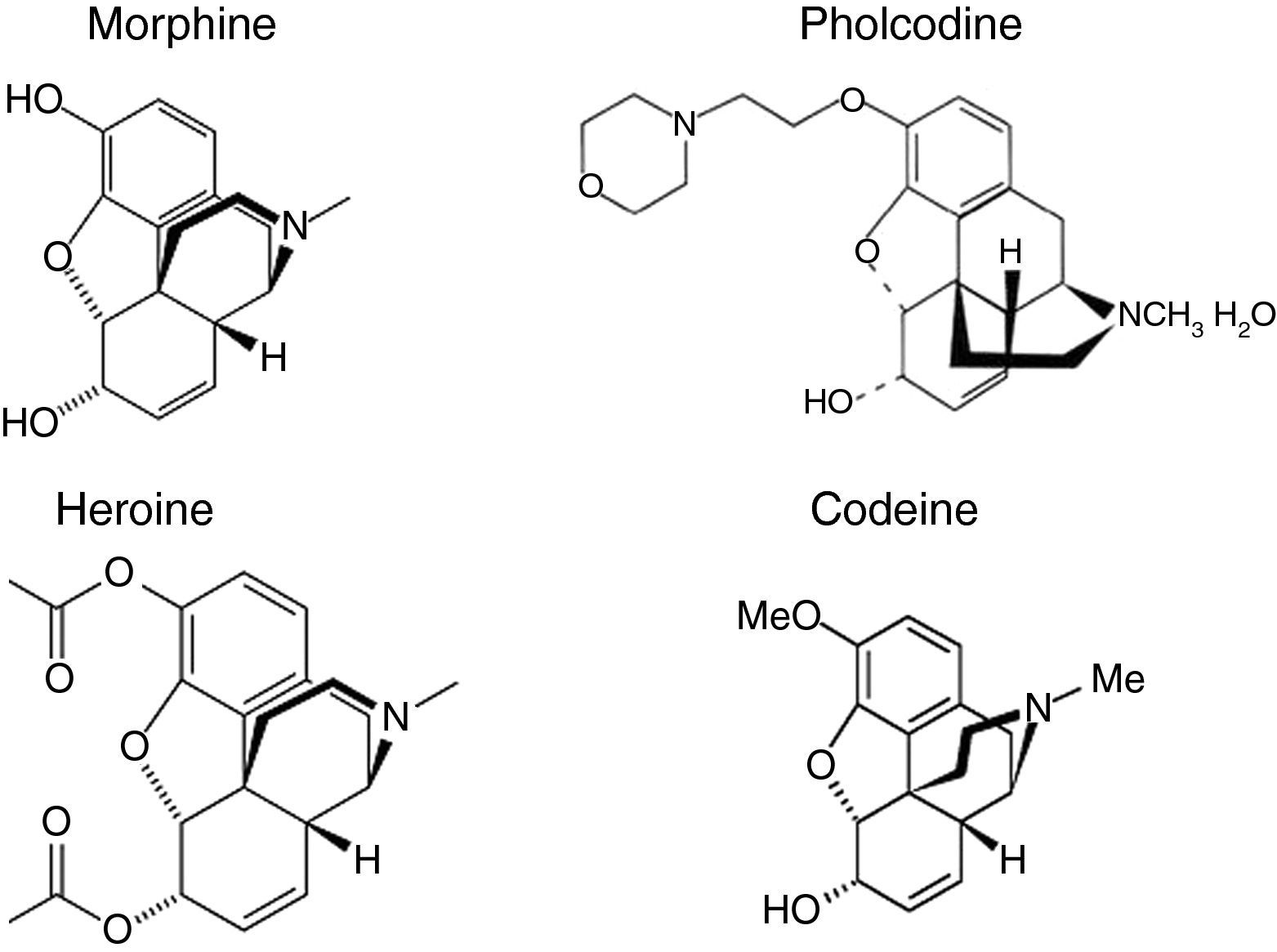

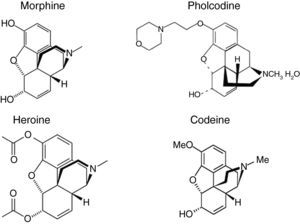

The structure of morphine is similar to the quaternary ammonium ion found in NMBA, which contains a hydrophobic ring skeleton and a hydrophilic tertiary amine (Fig. 1). It has been shown that morphine can be used to detect IgE antibodies against various NMBAs, enabling it to be used as a marker allergen for NMBA sensitisation.3 Cross-inhibition results indicate that some patients have IgE not only against the ammonium ion but also against the hydrophobic part of the morphine molecule.4

Three years ago we began a study on allergic sensitisation to different drugs in drug-abusers and allergic people. We found IgE sensitisation to cannabis sativa diagnosed by prick tests, bronchial challenge tests and specific IgE to cannabis extracts in patients who suffered from asthma and anaphylaxis after cannabis use, but could not obtain a reliable method of measurement of specific IgE to heroin (diacetylmorphine), which has a chemical structure similar to morphine (Fig. 1).

At that time, there was no commercialised morphine IgE detection method, and we used poppy seed ImmunoCAP®Allergen (Phadia, Sweden) as a subrogate allergen (see Fig. 2). Recently, Phadia (Uppsala, Sweden) has marketed two immunoassays: ImmunoCAP®Allergen c260 Quaternary Ammonium Morphine and ImmunoCAP® Allergen c261 Pholcodine. Pholcodine is an antitussive morphine derivative sold in many countries as an OTC drug, whose structure is similar to codeine (Fig. 1), a frequent cause of hypersensitivity reactions, and to the quaternary ammonium ions found in NMBA. It has been shown that pholcodine significantly increases levels of IgE antibodies to NMBA in sensitised patients.5,6

Cross-inhibition studies indicate that some patients have IgE not only against the ammonium ion, but also against the hydrophobic part of the pholcodine molecule.6 A recent clinical study showed that IgE tests using pholcodine have a somewhat higher sensitivity than suxametonium.7 ImmunoCAP® Pholcodine was also recently evaluated in a study with 25 patients allergic to rocuronium.7

The aim of this study was to assess the clinical value of morphine, pholcodine and poppy seed IgE determination (ImmunoCAP®) in people suffering hypersensitivity reactions during anaesthesia or analgesia with opium derived-drugs, and drug-abusers with allergic symptoms after heroin injection and to compare the usefulness of the three determinations as markers of clinical symptoms.

MethodsPatients and methodsWe carried out an observational case–control study. Patients were randomly selected from the registry of 23,873 patients attended in the last 23 years by the Allergy Clinic, Rio Hortega University Hospital of Valladolid: we found 25 patients who had suffered severe reactions (severe asthma, anaphylaxis) during anaesthesia or analgesia with opium derived-drugs; 20 patients who suffered anaphylactoid reactions after taking cough syrup (codeine or pholcodine); 50 heroin abusers who presented allergic symptoms (asthma or anaphylaxis) after heroin use; 40 patients sensitised to grass-pollen; 25 tobacco-sensitised patients who were users of antitussive drugs; and 11 patients who had suffered anaphylaxis due to penicillin.

After written informed consent was obtained, an epidemiological–clinical survey was carried out using the adverse drug reaction questionnaire employed in our hospital. This included the suspected drug, characteristics and origin of dependence (if any), possible adverse reactions (questioning of close friends or relatives), clinical symptoms, emergency department (ED) care and treatment required. Heroin abusers were recruited from the Association For the Aid of Drug Abusers (ACLAD). Pollen sensitivity was defined as: (a) ≥1 positive skin-prick test for pollen; (b) CAP (IgE) positive>0.35IU/mL for pollen; or (c) positive specific challenge.

Patients sensitised to tobacco who used cough syrups were included because most heroin abusers were smokers. This type of sensitisation is infrequent, and therefore all 25 patients attended over the last 23 years were included. Opiate consumption was self-estimated by patients as non-consumption, experimental, occasional, habitual, and dependence.

The control group comprised 200 non-smoking, non-atopic healthy blood donors (Blood Donation Unit, SACYL) who were non-users of illicit drugs and had never consulted our Allergy Clinic.

The protocol was evaluated and approved by Clinical Research Ethics Committees.

The following tests were carried out in all patients and controls:

In vivo testsSkin testsSkin tests, including allergens, using the European Group protocol for the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity8 were carried out for tobacco, morphine, pholcodine and poppy seeds; preliminary titration to determine the optimal concentration was performed. Histamine 1/100 and physiological saline solution were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Wheal area was measured after 15min and traced for posterior measurement by planimetry. A wheal≥19.62mm2, corresponding to a diameter of 5mm, was considered clearly positive, and was specified as a cut-off point after study of the ROC curves to exclude false positives due to irritation or non-specific liberation of histamine from mast cells.

Allergen extractsA standard battery of aeroallergens and foods including pollens (gramineae, trees, weeds and flowers), mites (Dermatophagoides and storage mites), fungi, antigens to animals and common foods (ALK-Abelló, Madrid, Spain) was administered. Extract of fresh tobacco leaf was prepared in our laboratory from uncured fresh leaves at a concentration of 1/10 weight/volume.

Preparation of opioid extractsMorphine and pholcodine extracts were used at a concentration of 1mg/mL.

Poppy seed extractPapaver somniferum seeds were cold-milled and defatted with acetone (2×1; 1:5 [weight/volume] for 1h at 4°C), and after drying, extracted with 0.1mol/L Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 10mM EDTA (1:5 [weight/volume] for 1h at 4°C). After centrifuging at 9000×g for 30min at 4°C, the supernatant was dialysed against H2O (cut-off point, 3.5kDa) and lyophilised. This extract, with a protein concentration of 5mg/mL, was used both for bronchial challenge and skin tests.

Diagnostic and pulmonary function testsSpecific bronchial challenge with P. somniferum seed extract was carried out in a blinded fashion, using the Chai technique with modifications as previously described.9 Seed extracts were diluted to 0.005mg/mL, 0.05mg/mL, 0.5mg/mL, 1mg/mL and 5mg/mL. After titration according to Gleich's technique with P. somniferum seed extract, the dilution that provoked a papule of 7mm2 was determined and was the initial dose used for the bronchial challenge carried out in consenting patients and controls.

After baseline spirometry, challenge was carried out if FEV1 was >80%. For poppy seed extract challenge, 2ml of extract were introduced in the dosimeter and the patient breathed normally for 2min. Spirometry was carried out and repeated at 5, 10, and 15min. If there was no change in FEV1 or if the reduction was >10%, the next higher concentration was used until a reduction in FEV1≥20%, considered as a positive bronchial challenge, was achieved. If the reduction in FEV1 was near to 15%, the patient inhaled the next higher dilution for 1min only.

In vitro testsSpecific IgESpecific IgE was determined for a battery of aeroallergens and foods: wheat, barley and rye, milk, alpha-lactalbumin, beta-lactoglobulin, casein, egg white and yolk, fish, and vegetables (vegetables, legumes, nuts, fresh fruits) tobacco, latex and tomato, using the ImmunoCAP System (Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden). Levels of IgE>0.35kU/L were considered positive. Biotynilated morphine, pholcodine and poppy seed extracts were coupled to Streptavidin-ImmunoCAP solid phase (Streptavidin-ImmunoCAP, Phadia AB, Uppsala, Sweden), according to Sander et al.10 Specific IgE to opium seed was determined by the ImmunoCAP System using the above-mentioned solid phases.

Statistical analysisThe association between study variables was analysed using Pearson's Chi2 test. When the number of cells with expected levels >5, were >20%, they were calculated using Fisher's exact test or the likelihood ratio test. Student's t-test for independent samples was used to compare means and when the number of groups to compare was greater, the ANOVA test was used. When these were not applicable, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test (for two groups) or Kruskal–Wallis H-test (for more than two groups) were used. Statistical significance was established as P<.05 and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated as necessary. The statistical analysis was made using the SPSS v15.0 statistical package.

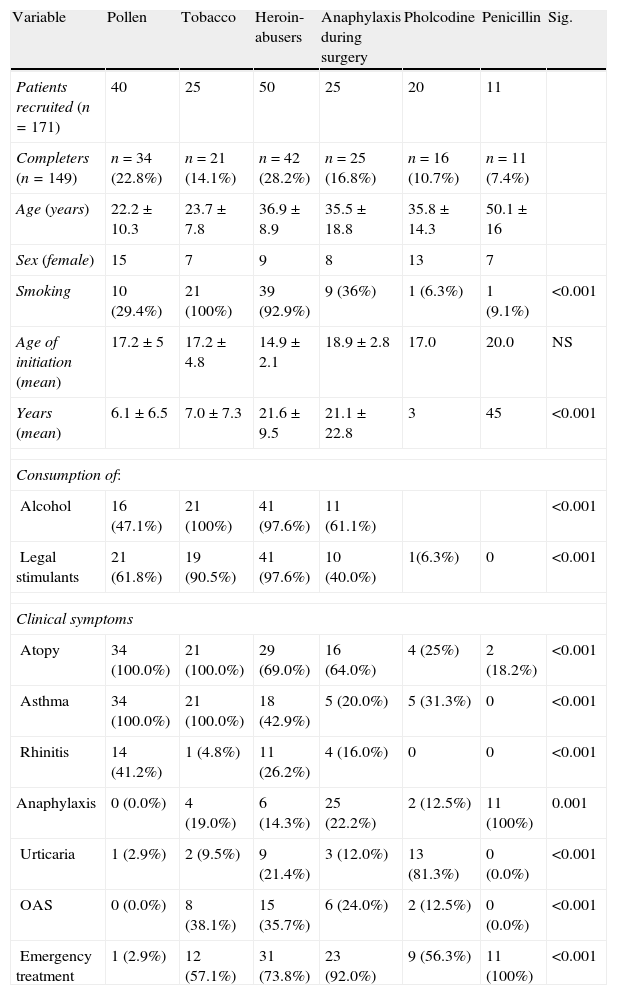

ResultsOne hundred and seventy-one patients and 200 controls were initially recruited: of these, 22 patients were lost to the study due to different causes (change of address or job, personal reasons) and thus 149 were finally analysed. Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the study patients.

Baseline characteristics of study patients.

| Variable | Pollen | Tobacco | Heroin-abusers | Anaphylaxis during surgery | Pholcodine | Penicillin | Sig. |

| Patients recruited (n=171) | 40 | 25 | 50 | 25 | 20 | 11 | |

| Completers (n=149) | n=34 (22.8%) | n=21 (14.1%) | n=42 (28.2%) | n=25 (16.8%) | n=16 (10.7%) | n=11 (7.4%) | |

| Age (years) | 22.2±10.3 | 23.7±7.8 | 36.9±8.9 | 35.5±18.8 | 35.8±14.3 | 50.1±16 | |

| Sex (female) | 15 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 13 | 7 | |

| Smoking | 10 (29.4%) | 21 (100%) | 39 (92.9%) | 9 (36%) | 1 (6.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | <0.001 |

| Age of initiation (mean) | 17.2±5 | 17.2±4.8 | 14.9±2.1 | 18.9±2.8 | 17.0 | 20.0 | NS |

| Years (mean) | 6.1±6.5 | 7.0±7.3 | 21.6±9.5 | 21.1±22.8 | 3 | 45 | <0.001 |

| Consumption of: | |||||||

| Alcohol | 16 (47.1%) | 21 (100%) | 41 (97.6%) | 11 (61.1%) | <0.001 | ||

| Legal stimulants | 21 (61.8%) | 19 (90.5%) | 41 (97.6%) | 10 (40.0%) | 1(6.3%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Clinical symptoms | |||||||

| Atopy | 34 (100.0%) | 21 (100.0%) | 29 (69.0%) | 16 (64.0%) | 4 (25%) | 2 (18.2%) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 34 (100.0%) | 21 (100.0%) | 18 (42.9%) | 5 (20.0%) | 5 (31.3%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Rhinitis | 14 (41.2%) | 1 (4.8%) | 11 (26.2%) | 4 (16.0%) | 0 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Anaphylaxis | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (19.0%) | 6 (14.3%) | 25 (22.2%) | 2 (12.5%) | 11 (100%) | 0.001 |

| Urticaria | 1 (2.9%) | 2 (9.5%) | 9 (21.4%) | 3 (12.0%) | 13 (81.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| OAS | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (38.1%) | 15 (35.7%) | 6 (24.0%) | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| Emergency treatment | 1 (2.9%) | 12 (57.1%) | 31 (73.8%) | 23 (92.0%) | 9 (56.3%) | 11 (100%) | <0.001 |

OAS: oral allergy syndrome.

Eighty-seven (58.4%) patients had suffered severe allergic attacks requiring emergency treatment, most-commonly for asthma (83, 55.7%), anaphylaxis (48, 32.2%) and urticaria (28, 18.8%).

Twenty-four of these 87 patients (16.1%) had positive prick tests for morphine, 15 (10.1%) for codeine and 33 (22.1%) for poppy seeds. None of these patients had positive-specific IgE to morphine or codeine but 51 (34.22%) had positive IgE to poppy seeds.

The percentage of patients with positive tobacco prick test (26.8%) was concordant with positivity of tobacco-specific IgE (27.5%) and more positive prick tests with opioids were observed in tobacco-sensitised patients (10/40, 25%) (P<.001).

Five of the prick tests performed in the 200 blood donor volunteers were positive for morphine, 16 for codeine and 4 for poppy seeds. Forty-eight patients and 52 controls consented to bronchial challenge with poppy seed extract. The challenge was positive in 27.8% of tobacco-sensitised patients; 31% of heroin abuses; 27.3% of patients presenting anaphylactic symptoms after anaesthesia; and 25% of patients taking pholcodine. No controls had a positive challenge. Drug consumption history and the results of prick tests, specific IgE and bronchial challenge of study patients are shown in Table 2.

Drug consumption and allergic tests in study patients.

| Variable | All n=149 | Pollen | Tobacco | ACLAD | Morphine | Pholcodine | Sig. |

| Allergy tests | |||||||

| Positive morphine | 24 (16,1%) | 0/34 (0.0%) | 4/21 (19%) | 1/42 (2.4%) | 13/25 (52%) | 4/16 (25%) | <0.001 |

| Prick test | |||||||

| Positive morphine | 0 (0.0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS |

| IgE | |||||||

| Positive pholcodine | 15 (10.1%) | 0/34 (0.0%) | 1/21 (4.8%) | 4/42 (9.5%) | 4/25 (16%) | 6/16 (37.5%) | <0.001 |

| Prick test | |||||||

| Positive pholcodine IgE | 0 (0.0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Positive opium | 33 (22.1%) | 0/34 (0.0%) | 5/21 (23.8%) | 12/42 (28.6%) | 13/25 (52.0%) | 3/16 (18.8%) | <0.001 |

| Prick test | |||||||

| Positive opium specific IgE | 51 (34.22%) | 0/34 (0.0%) | 5/21 (23.8%) | 9/42 (21.4%) | 33/25 (52.0%) | 4/16 (25%) | <0.001 |

| Positive opium bronchial challenge | 23/48 47.9% | 0/34 (0.0%) | 5/18 (27.8%) | 18/42 (42.85%) | 3/11 (27.3%) | 2/8 (25%) | NS |

| Self-estimated opioid consumption | |||||||

| Never | 77 (51.7%) | 30 (88.2%) | 5 (23.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 16 (64.0%) | 15 (93.8%) | <0.001 |

| Experimental | 15 (10.1%) | 3 (8.8%) | 5 (23.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (24.0%) | 1 (6.3%) | <0.001 |

| Occasional | 13 (8.7%) | 1 (2.9%) | 10 (47.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (8.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| Habitual | 2 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| Dependence | 42 (28.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 42 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| Tobacco | 21 (14.1) | 10 (29.4%) | 21 (100%) | 39 (92.9%) | 9 (36.0%) | 1 (6.3%) | <0.001 |

| Age initiation | 16±2.6 | 17.2±5 | 17.2±4.8 | 14.9±2.1 | 18.9±2.8 | 17.0 | NS |

| Mean years consumption | 15.9±13.3 | 6.1±6.5 | 7±7.3 | 21.6±9.5 | 21.1±22.8 | 3.0 | <0.001 |

| Cocaine | 38 (25.5) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.8%) | 37 (88.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| Age initiation (years) | 17.5±2.5 | – | 20 | 17.4±2.5 | – | – | NS |

| Mean years consumption | 19.1±8.9 | – | 18 | 19.1±8.9 | – | – | 0.001 |

| Heroin | 36 (24.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 | 31 (73.8%) | 5 | – | <0.001 |

| Age initiation | 19.2±4.3 | – | – | 18.1±3.1 | 25.8±5.5 | – | NS |

| Mean years consumption | 19.2±11.6 | – | – | 20.4±8.4 | 11.6±23.7 | – | NS |

| Methadone | 21 (14.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 21 (50%), | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| Age initiation | 33.7±8.5 | – | 0 | 33.7±8.5 | 0 | – | NS |

| Mean years consumption | 3.9±2.4 | – | 0 | 3.9±2.4 | 0 | – | NS |

| Amphetamines | 17 (11.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (9.5%) | 12 (28.6%) | 2 (8.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| Benzodiazepines | 27 (18.1%) | 0 | 1 (4.8%) | 24 (57.1%) | 2 (8.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| Legal stimulants | 92 (61.7%) | 25 (100%) | 19 (90.5%) | 41 (97.6%) | 14 (77.8%) | NS | |

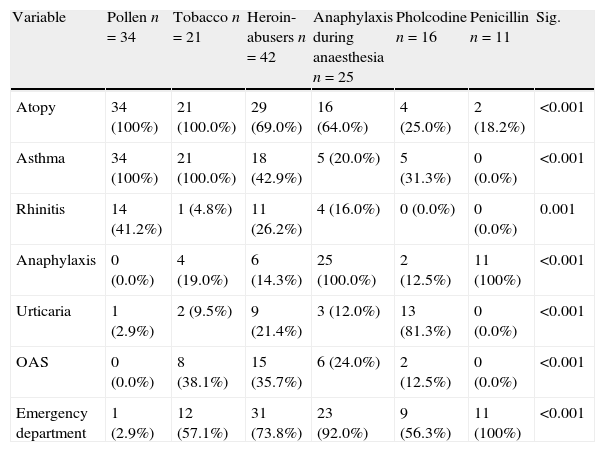

Differences in clinical variables according to study groups are shown in Table 3.

Differences in clinical variables according to study group.

| Variable | Pollen n=34 | Tobacco n=21 | Heroin-abusers n=42 | Anaphylaxis during anaesthesia n=25 | Pholcodine n=16 | Penicillin n=11 | Sig. |

| Atopy | 34 (100%) | 21 (100.0%) | 29 (69.0%) | 16 (64.0%) | 4 (25.0%) | 2 (18.2%) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 34 (100%) | 21 (100.0%) | 18 (42.9%) | 5 (20.0%) | 5 (31.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| Rhinitis | 14 (41.2%) | 1 (4.8%) | 11 (26.2%) | 4 (16.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.001 |

| Anaphylaxis | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (19.0%) | 6 (14.3%) | 25 (100.0%) | 2 (12.5%) | 11 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Urticaria | 1 (2.9%) | 2 (9.5%) | 9 (21.4%) | 3 (12.0%) | 13 (81.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| OAS | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (38.1%) | 15 (35.7%) | 6 (24.0%) | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| Emergency department | 1 (2.9%) | 12 (57.1%) | 31 (73.8%) | 23 (92.0%) | 9 (56.3%) | 11 (100%) | <0.001 |

OAS: Oral allergy syndrome.

Thirty-one patients (73.8%) had attended the emergency department (ED), due to anaphylaxis in six (14.3%) cases; asthma in 18 (42.9%); and urticaria/angio-oedema in nine (21.4%). Both wheal areas and levels of IgE to poppy seed were higher in heroin abusers (P<.001). Of the 18 asthmatic patients, 12 presented altered respiratory function tests (obstructive spirometry) at baseline and all had a positive bronchial challenge for poppy seeds.

Patients with pollen allergyThere were three experimental and one occasional user of inhaled heroin but no habitual or dependent users. The most frequent disorders were rhinitis and asthma. No patient had suffered from anaphylaxis or angio-oedema but one had attended the ED due to urticaria.

Patients allergic to tobaccoFive patients were experimental heroin users, one habitual and none a dependent user.

All were users of antitussive-codeine drugs. Five patients sensitised to poppy seeds had attended the ED, four due to asthma and one to anaphylaxis (a heroin, tobacco and alcohol user).

Patients suffering anaphylaxis during anaesthesiaOf the 25 patients, six were occasional users of opioid analgesics, two occasional, and one habitual user of heroin and none was a dependent user. Prick tests were positive for morphine in 13 patients (52%), codeine in 4 (16%) and poppy seed in 13 (52%, who also had positive IgE to poppy seeds). One male patient who died during surgery had specific IgE to poppy seed of 6.46kU/L and was an occasional user of opiate analgesics and heroin.

Patients suffering anaphylactoid reactions after taking cough syrupThe most common symptoms were urticaria (81.3%) and asthma (31.3%). Only two patients suffered anaphylaxis. Four (25%) patients had positive prick test for morphine, six (37.5%) for pholcodine and three (18.8%) for poppy seed. Four patients had positive specific IgE to poppy seed and none to morphine or pholcodine. Two of the five asthmatic patients had positive bronchial challenge to poppy seed.

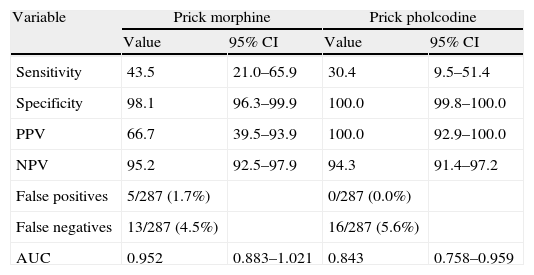

Yield of diagnostic testsIn the study patients, the poppy seed prick test had a better sensitivity (95.6) and specificity (100%) in the diagnosis of opiate allergy than morphine prick tests. Specific IgE to opium seeds had a sensitivity of 82.6% and a specificity of 100% (Table 4).

Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, false positives and false negatives of morphine, pholcodine and opium seeds tests.

| Variable | Prick morphine | Prick pholcodine | ||

| Value | 95% CI | Value | 95% CI | |

| Sensitivity | 43.5 | 21.0–65.9 | 30.4 | 9.5–51.4 |

| Specificity | 98.1 | 96.3–99.9 | 100.0 | 99.8–100.0 |

| PPV | 66.7 | 39.5–93.9 | 100.0 | 92.9–100.0 |

| NPV | 95.2 | 92.5–97.9 | 94.3 | 91.4–97.2 |

| False positives | 5/287 (1.7%) | 0/287 (0.0%) | ||

| False negatives | 13/287 (4.5%) | 16/287 (5.6%) | ||

| AUC | 0.952 | 0.883–1.021 | 0.843 | 0.758–0.959 |

| Variable | Prick poppy seed | IgE poppy seed | ||

| Value | 95%CI | Value | 95%CI | |

| Sensitivity | 95.6 | 85.1–100.0 | 82.6 | 64.9–100.0 |

| Specificity | 100.0 | 99.2–100.0 | 100.0 | 99.2–100.0 |

| PPV | 100.0 | 97.7–100.0 | 100.0 | 97.4–100.0 |

| NPV | 98.5 | 94.7–100.0 | 94.1 | 87.8–100.0 |

| False positives | 0/87 (0.0%) | 0/87 (0.0%) | ||

| False negatives | 1/87 (1.1%) | 4/87 (4.6%) | ||

| AUC | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.913 | 0.821–1.005 |

PPV: positive predictive area; NPV: Negative predictive area; AUC: Area under the curve.

The aim of our study was to assess the clinical value of morphine, pholcodine and opium seed IgE determination (ImmunoCAP®) in allergic people suffering hypersensitivity reactions during anaesthesia, and drug-abusers with allergic symptoms after heroin injection and to compare the clinical usefulness of three IgE determinations (InmunoCAP allergen morphine, pholcodine and poppy seeds) as markers of clinical symptoms.

Our results showed that prick areas and levels of specific IgE to poppy seeds were greater in patients suffering anaphylaxis after anaesthesia, followed by heroin abusers and tobacco-sensitised patients (P<.001). Sensitisation to pollen was not a risk factor for opiate sensitivity. Neither the severity of the clinical profiles nor a history of ED admission was related to the level of opiate consumption, with occasional users of opiates also at risk. The most severe reactions (anaphylaxis) were more frequent in patients sensitised to opiates (70.8% in patients with hypersensitivity against 28.8% in non-sensitised patients (P<.001). Both the prick test and specific IgE to poppy seeds were efficient in detecting sensitisation to opiates and positivity was related to severe clinical profiles (anaphylaxis, asthma, angio-oedema) requiring emergency treatment.

Drug misuse and asthma are major health problems in urban settings.11 After heroin (diacetylmorphine)-assisted treatment was initiated in chronic treatment-resistant heroin-dependent Dutch patients, Hogen et al.12 reported work-related eczema, positive heroin patch tests and nasal and respiratory complaints in some nurses and concluded that these may have been due to the histamine-liberating effect of heroin, to atopic constitution, to a combination of these factors or – less likely – to other non-allergic factors. Other reports have described cases of allergic symptoms (asthma and anaphylaxis) after heroin consumption.13–19 The known ability of opiates to non-specifically stimulate the liberation of histamine and other constituents of mast cell granules offers one explanation for these observations. Some studies have suggested that many heroin fatalities were caused by an anaphylactoid reaction, but not by an IgE-mediated response. The major problems were that skin prick testing was not considered useful in the diagnosis of opiate sensitivity and there was no commercially available opiate-specific IgE. The value of skin prick testing in opiate-sensitive individuals is uncertain, as opiates seem to cause non-specific wheals by direct degranulation of mast cells.20

Anaphylactic reactions to NMBA during general anaesthesia are a major cause of concern and a source of debate among anaesthesiologists. A cough syrup containing pholcodine has emerged as the most likely suspect, leading to the withdrawal of the drug from the Norwegian market and examination of the role of pholcodine-containing drugs in other countries.21 Codeine, whose chemical structure is very similar to pholcodine, morphine and heroin, is widely used in Spain as a cough syrup and is a common cause of allergy-like symptoms.22–24 Cough syrups with codeine are also used by heroin abusers as a substitute.

Cross-reactivity among NMBA is common since they all share the quaternary ammonium ion allergenic epitope.2 However, the extent of cross-reactivity varies considerably and it is unusual for an individual to be allergic to all NMBA.7 The explanation for this limitation in cross-reactivity is that IgE antibody paratopes may not only recognise the quaternary ammonium ion; sometimes, the molecular environment around the ammonium ion is also part of the allergenic epitope.4 The possibility of multiple allergies should therefore be considered.

The rationale for studying IgE poppy seed determination was that in a previous study, we found that positive IgE to poppy seeds had a high sensitivity and specificity in identifying patients suffering allergic symptoms after heroin injection. Hypersensitivity to poppy seeds is uncommon and may develop due to immune (allergy) and non-immune reactions, and can have a devastating course. Other reports have found occupational asthma in six workers in a factory producing morphine25 and isolated cases of anaphylaxis after consumption of food containing poppy seeds.26–32 Poppy seeds are often added to bread and tea in some European countries but not usually in Spain.

In summary, opiates can provoke life-threatening allergic attacks and should be considered in patients who are candidates for surgery or analgesia or those at risk of abusing drugs who have poorly controlled asthma. Opiate (morphine, heroin, codeine and pholcodine) hypersensitivity can be tested using a simple and reliable method such as the prick test and determination of specific IgE to poppy seeds.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

This work was subsidised by the General Direction of Public Health, Sanidad Castilla y León (SACYL) Valladolid, Spain.

We sincerely thank our patients, especially the ACLAD patients, for their courage and interest. They deserve our best efforts in the fight to overcome their addiction. Many ACLAD patients were on methadone and also had other problems (prostitution, sexually transmitted diseases, hepatitis, AIDS). However, they were very receptive to any positive health intervention on their behalf. The authors thank David Buss for his editorial assistance.