Asthma is a complex, chronic inflammatory disease of the lower airways affecting people of all ages. Approximately 300 million individuals are currently suffering from asthma worldwide. The prevalence of asthma is estimated to range from 3% to 38% in children and from 2% to 12% in adults. The disease causes lost school and work days, limitations in daily activities, and sleep disturbances. Lung function impairment also occurs, resulting in decreased quality of life unless disease control is achieved and a high annual financial burden is incurred. Achievement and maintenance of control through assessment of clinical manifestations and future risk has become the aim of treatment over the years. Unfortunately, the desired level of asthma control has not been achieved in a considerable number of regions throughout the world, and the level of control is overestimated by both patients and their parents. This review examines the mortality and morbidity rates for asthma, emphasizes the challenges inherent to control management, and provides data on the tools used to measure control level.

Asthma is a complex, chronic inflammatory disease of the lower airways characterised by variable airflow obstruction and airway hyper-responsiveness. Asthma occurs as a consequence of both patient-related and environmental factors and affects people of all ages.

Prevalence, incidence, mortality, and morbidityApproximately 300 million individuals are currently suffering from asthma worldwide.1 The prevalence of asthma is estimated to range from 3% to 38% among children and from 2% to 12% among adults.2 The International Study of Asthma and Allergies (ISAAC) Phase 1 and Phase 3 provided a huge amount of data on the prevalence of asthma and the changes in asthma prevalence during five to ten year periods among children worldwide.3 In the phase 1 study, the 12-month prevalence of asthma symptoms was highest in medical centres in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and the Republic of Ireland, followed by some centres in North, Central and South America. In the phase 3 study, the prevalence of asthma in 6–7-year-old children increased in centres in Asia-Pacific, India, North America, the eastern Mediterranean, and Western Europe. An increase was also observed among 13–14-year-old children primarily in centres in Africa, Latin America, and northern and eastern Europe, as well as Asia-Pacific and India. Asthma symptom prevalence decreased significantly in English language countries which were previously found to have high prevalences.4 Although variation exists among countries, all countries reported that the lifetime asthma prevalence had increased,4 and worldwide data also showed an overall rise in asthma prevalence.2

Additionally, the asthma incidence rate has been increasing for both male and female adults over time, with higher estimates for women.5 A review of studies published between 1974 and 2004 estimated the incidence of asthma in adults as 3.6 and 4.6 asthma cases per 1000 person-years for men and women, respectively.5 There is now evidence of a plateau in asthma incidence among children. The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention collected data on the status of childhood asthma in the U.S.A. between 1980 and 2007. They determined that, although asthma prevalence increased from 3.6% in 1980 to 7.5% in 1997, the lifetime, current symptom, and asthma attack prevalences remained stable between 1997 and 2007, revealing a plateau.6 Most recent studies have demonstrated similar results for adults7 and for children8 from different parts of Europe.

The annual death rate due to asthma is estimated to be 250,000,1 and the majority of deaths occur in low and middle income countries. The World Health Organisation estimates that 15 million disability-adjusted life years are lost annually due to asthma; asthma, therefore, represents 1% of the total global disease burden.9 Patients from low- and middle-income countries have more severe symptoms than those in high-income countries, possibly due to incorrect diagnoses, poor access to health care, the unaffordability of therapy, exposure to environmental irritants, and genetic susceptibility to more severe disease.10

Asthma gives rise to lost work and school days, significant economic burden due to exacerbations, lung function impairment, limitations in daily activities, and sleep disturbances, resulting in decreased quality of life unless the disease is carefully controlled. For example, a nationwide multicentre cross-sectional study from Turkey determined the following: 44.2% of patients who had been followed for at least one year by tertiary allergy clinics had required at least one unscheduled visit; 29.9% had required emergency admission; and 13.6% had required hospitalisation during the previous year. Furthermore, 74.6% missed at least one day of school due to asthma, and 51.3% missed work days.11 The annual cost per patient was approximately 1500 US dollars,12 a cost comparable to that of patients in developed countries. As demonstrated by these two studies, the level of asthma control must be improved to lower the economic burden, morbidity and mortality.

What does “control” mean in asthma?While previously disease management was based on a severity index, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) changed the aim of asthma treatment to achieving asthma control and maintaining control for long periods. The GINA has adopted a five-step approach to asthma control in which each step represents a different treatment option with increasing efficacy.1 The five-step approach is designed to maintain control with the least amount of medication.

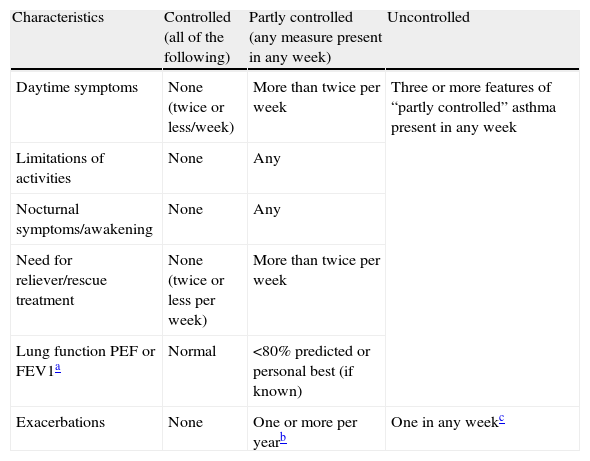

The term “control” involves the assessment of both clinical manifestations and future risk to the patient.13 Clinical manifestations include the frequency of current daytime and nocturnal symptoms, sleep disturbances, and limitations in daily activities. Additionally, the frequency at which a reliever/rescue treatment was required in the last four weeks, together with spirometric evaluation (peak expiratory flow (PEF) or forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1)), determine the ‘impairment’ domain. The assessment of future risk is based on the frequency of exacerbations which required systemic steroids in the last year, as well as any rapid decline in lung function or side effects of treatment.1,14 The GINA guidelines classify patients into three categories according to the level of control (Table 1) in a manner similar to the NAEPP guidelines. Asthma guidelines focus on achieving and maintaining asthma control while balancing the risks associated with medications. The guidelines also recommend that, if the asthma is currently uncontrolled, treatment must be stepped up until control is achieved. An increase in therapy can also be considered if the asthma is partly controlled. In other words, treatment must be continued until complete control is achieved; control of one or a few individual outcomes is not sufficient.15 After control has been established, treatment should be maintained for at least three months.

Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) definitions of asthma control.

| Characteristics | Controlled (all of the following) | Partly controlled (any measure present in any week) | Uncontrolled |

| Daytime symptoms | None (twice or less/week) | More than twice per week | Three or more features of “partly controlled” asthma present in any week |

| Limitations of activities | None | Any | |

| Nocturnal symptoms/awakening | None | Any | |

| Need for reliever/rescue treatment | None (twice or less per week) | More than twice per week | |

| Lung function PEF or FEV1a | Normal | <80% predicted or personal best (if known) | |

| Exacerbations | None | One or more per yearb | One in any weekc |

PEF: peak expiratory flow; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1s.

Until recently, the term ‘severity’ was used extensively in the assessment of the treatment needs of asthmatic patients and was considered interchangeable with the term ‘control’. However, these two terms describe distinct concepts.16 Nowadays, severity is defined as the intensity of treatment needed to achieve and maintain good control. For example, severe asthma is defined by the requirement for high intensity treatment. Patients with severe asthma include both those with poor control and frequent exacerbations despite high intensity treatment and those who can only maintain good control while receiving high intensity treatment. However, in daily clinical practice, to specify the control level of the patient and to increase therapy when necessary is less complex.15 Furthermore, cross-sectional studies worldwide have shown that the use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and reliever medication is independent of patients’ asthma severity gradings.17,18

Global control levelsThe Asthma Insights and Reality (AIR) surveys were conducted globally to determine the level of control, as defined by the GINA guidelines, in different parts of the world. The AIR surveys started in the United States in 1998, followed by surveys in Europe (AIRE) in 1999, in Japan in 2000, and in central and eastern Europe in 2001. When all the data were analysed together, the majority of patients (51–74%) had daytime symptoms; 41–59% experienced sleep disturbances; 33–59% had exercise-induced symptoms; and the rate of limitations in daily activities ranged from 17% in Japan to 68% in central and eastern Europe.19 Of the patients who completed the AIRE survey, only 5.3% met all the criteria for asthma control; 30.5% of adults and 28% of children reported sleep disturbances at least once a week; 19.1% of children and 37.9% of adults reported limitations in normal physical activity due to asthma; and 42.7% of children and 17.1% of adults reported school/work absences due to asthma.17 The AIR survey in Turkey (AIRET) revealed a huge discrepancy between guideline-based control level classifications of the patients and their own perceptions. Only 1.3% of all participants achieved guideline-based asthma control. However, 45% of participants believed that their asthma was either completely or well-controlled.20 In the CAPTURE study, patients’ perceptions of their childhood asthma were analysed using a questionnaire. At least 40% of the children continued to experience coughing, dyspnoea and wheezing; 60% experienced exercise-induced symptoms more than once a week; 40% of adolescents experienced sleep disturbances; and 25% had wheezing and exercise-induced symptoms more than once a week.21 In a more recent study conducted in six different countries, only 4% of the children and adolescents described their asthma as being “very bad”, while more than half reported that they woke up during the night due to their asthma. These results reveal underestimation of the severity of asthma and overestimation of its control by paediatric asthmatics.22 In the second part of the study, parental perceptions related to the control and severity levels of asthma in their children were found to be similarly inaccurate, unfortunately.23

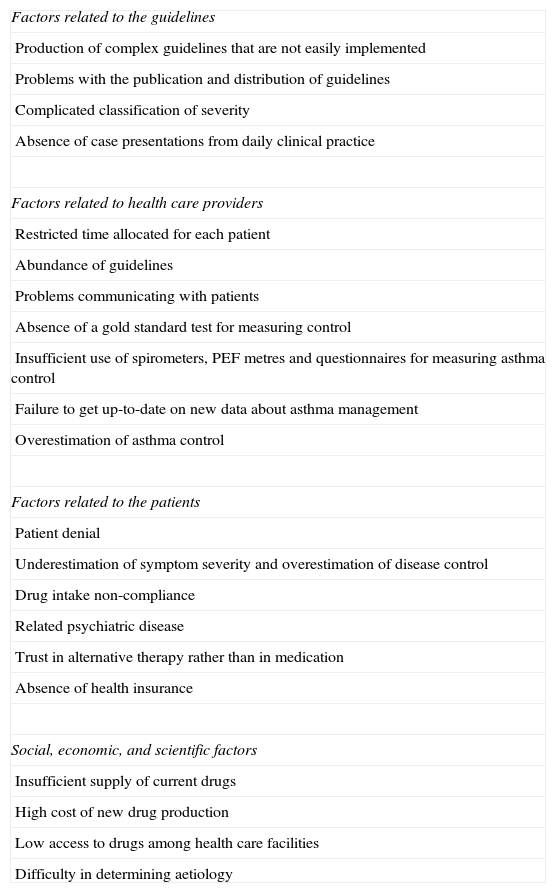

The underlying reasons for low levels of controlThere are many possible reasons for low asthma control levels worldwide (Table 2). In a review of asthma programmes and projects around the world, the rates of exposure to and application of national and international asthma guidelines were found to be low in diverse regions. The absence of medical education programmes and training for health care providers, and insufficient access to drugs for patients were found to contribute to the low levels of control.10 Physicians often do not ask enough questions to accurately determine and document whether asthma is under control.24 To establish widespread successful control, governments, health care organisations, medical professionals, and the pharmaceutical industry must first agree on management programme policies. National and regional epidemiological data on the burden of asthma, asthma risk factors, and methods to reduce risk must then be determined and disseminated to all health care providers. Regular training programmes covering new issues in management of control must be provided to health care professionals, especially those in primary care centres. Patients must have easy access to health care centres in which lung function can be measured. Patients must also be educated on the use of different types of inhaled medication. A partnership with the patient and the family must be built, and the goals of treatment and asthma care should be explained.25 Patients must be monitored on a regular basis and trained on when and how to manage their asthma.10

Challenges in the management of asthma control.

| Factors related to the guidelines |

| Production of complex guidelines that are not easily implemented |

| Problems with the publication and distribution of guidelines |

| Complicated classification of severity |

| Absence of case presentations from daily clinical practice |

| Factors related to health care providers |

| Restricted time allocated for each patient |

| Abundance of guidelines |

| Problems communicating with patients |

| Absence of a gold standard test for measuring control |

| Insufficient use of spirometers, PEF metres and questionnaires for measuring asthma control |

| Failure to get up-to-date on new data about asthma management |

| Overestimation of asthma control |

| Factors related to the patients |

| Patient denial |

| Underestimation of symptom severity and overestimation of disease control |

| Drug intake non-compliance |

| Related psychiatric disease |

| Trust in alternative therapy rather than in medication |

| Absence of health insurance |

| Social, economic, and scientific factors |

| Insufficient supply of current drugs |

| High cost of new drug production |

| Low access to drugs among health care facilities |

| Difficulty in determining aetiology |

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are the cornerstone of asthma treatment for all age groups, and guidelines from all countries advocate the use of ICS for the treatment of persistent disease. Treatment with ICS decreases asthma mortality and morbidity, reduces symptoms, improves lung function, reduces bronchial hyper-responsiveness, and reduces the number of exacerbations.14 Moreover, ICS are generally well-tolerated by both children and adults and adverse events tend to be minimal if a low to medium dose is used.14 However, concerns about adverse effects remain and are particularly associated with sustained high doses.

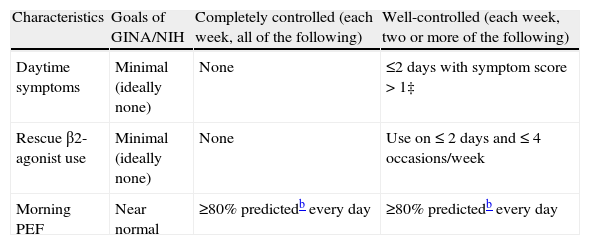

The presence of a considerable amount of uncontrolled asthma patients with respect to guidelines brought to mind that there were limitations or problems in treatment strategies. To clarify this point, the Gaining of Asthma Control (GOAL) study was conducted on patients with uncontrolled asthma. In this study, asthma treatments were analysed to determine whether they were able to achieve and maintain the desired control levels, defined in the guidelines.26 The aim of the study was to compare the efficacy of two recommended controller medications (ICS alone versus long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA) plus ICS) in achieving good or total asthma control as defined by the GINA and NIH guidelines26 (Table 3).

Definitions of well-controlled and completely-controlled asthma based on the Global Initiative for Asthma/National Institutes of Health guidelines.26

| Characteristics | Goals of GINA/NIH | Completely controlled (each week, all of the following) | Well-controlled (each week, two or more of the following) |

| Daytime symptoms | Minimal (ideally none) | None | ≤2 days with symptom score > 1‡ |

| Rescue β2-agonist use | Minimal (ideally none) | None | Use on ≤ 2 days and ≤ 4 occasions/week |

| Morning PEF | Near normal | ≥80% predictedb every day | ≥80% predictedb every day |

| Characteristics | Goals of GINA/NIH | Completely controlled (each week, all of the following) | Well-controlled (all of the following) |

| Night-time sleep disturbances | Minimal (ideally none) | None | None |

| Exacerbationsa | Minimal (infrequent) | None | None |

| Emergency visits | None | None | None |

GINA=Global Initiative for Asthma; NIH=National Institutes of Health; PEF=Peak expiratory flow

Completely- and well-controlled asthma were defined by achievement of all of the specified criteria for a given week. Completely-controlled asthma was achieved if the patient recorded seven totally controlled weeks and had no exacerbations, emergency room visits, or medication-related adverse events during the eight consecutive assessment weeks. Well-controlled asthma was similarly assessed over the eight weeks. All assessments were performed over eight weeks during the double-blind treatment period. Baseline control and control during the open-label phase were assessed over a four-week period.

Well-controlled or completely-controlled asthma was achieved in 71% and 42% of patients in the LABA plus ICS group and the ICS group, respectively, proving that much higher levels of asthma control can be achieved using current treatments than those found in the AIR surveys. Patients who achieved control experienced a very low number of exacerbations and recorded near maximal health status scores.26 These data suggest that the asthma control level determines the risk of having an exacerbation. Additionally, for patients with the same level of control, the risk of having an exacerbation was independent of the medication used. The next phase of the study was about maintenance of control. Control was maintained for a median of almost three months in totally-controlled patients and six months in well-controlled patients respectively, showing that the control level is important for its maintenance.27

Besides the GOAL study, other studies have analysed the effects of treatment strategies on asthma control using different items of control. In patients with mild persistent asthma, early intervention with budesonide was associated with a lower risk of hospitalisation, emergency admission and death from asthma and less need of additional medication, such as extra doses of ICS or LABA.28

In the CAMP study, 1041 children with mild to moderate asthma were treated with budesonide, nedocromil or a placebo for four to six years. During this period, budesonide treatment significantly reduced the symptom score, the number of sleep disturbances/month, and the use of albuterol (from 10 to three puffs/week), and increased the number of episode-free days.29

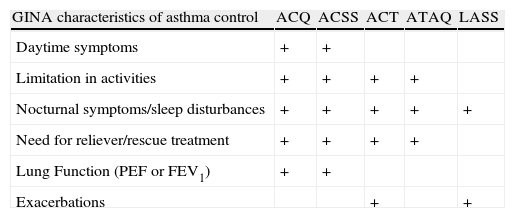

Measuring control levelsPhysicians in daily clinical practice need practical tools for determining patients’ control levels and for quantifying each patient's improvement during the course of the disease. Tools are also needed to aid physicians in deciding whether to increase therapy doses. Several different instruments are available which vary in applicability in daily practice.30 Five validated tests have been identified, and features of each were previously presented, in accordance with GINA guidelines, in a review30 (Table 4).

The ability of asthma control instruments to assess the control characteristics outlined in the GINA guidelines.30

| GINA characteristics of asthma control | ACQ | ACSS | ACT | ATAQ | LASS |

| Daytime symptoms | + | + | |||

| Limitation in activities | + | + | + | + | |

| Nocturnal symptoms/sleep disturbances | + | + | + | + | + |

| Need for reliever/rescue treatment | + | + | + | + | |

| Lung Function (PEF or FEV1) | + | + | |||

| Exacerbations | + | + |

ACQ: Asthma Control Questionnaire; ACSS: Asthma Control Scoring System; ACT: Asthma Control Test; ATAQ: Asthma Assessment Questionnaire; LASS: Lara Asthma Symptom Scale; GINA: Global Initiative for Asthma.

The asthma control questionnaire (ACQ) has been widely used. The ACQ is the only tool of the five which has been validated in persons 17 years of age or older, and a paediatric version has also been recently tested.31 The ACQ includes six clinical questions, two related to shortness of breath and wheezing and four GINA questions along with measurement of FEV1. Each question is scored between 0 and 6 (0: no impairment, 6: maximum impairment). The ACQ results are determined by taking the mean of all seven items. Seven-, six- and five-item versions have been validated for measuring asthma control based on GINA and NIH guidelines32 and the control parameters determined in the GOAL study.33 A score of 1.5 was defined as the cut-off point for poorly-controlled asthma, and a score of 0.75 was defined as the cut-off point for well-controlled asthma.

The asthma control scoring system (ACSS) assesses clinical, physiological (PEF, FEV1 and ΔPEF) and inflammatory parameters (sputum eosinophilia) and is composed of eight items in total. The ACSS defines control as the mean percentage in which 100% represents the best control. The ACSS has demonstrated good test-retest reliability, good internal consistency and moderate correlations with the mini-asthma quality of life questionnaire and the ACQ.34

The Asthma Control Test (ACT) is based on the patient's own perception of asthma control. The sum of the scores ranges from 5 (poor control) to 25 (complete control). A patient with a score of 15 or lower is classified as having poor control. The ACT is easy to apply and is the most widely-used tool in daily clinical practice. The ACT has been shown to be reliable, valid and capable of identifying patients with poor asthma control among patients older than 12 years (the five-item version)35 and between the ages of four and 11 years (seven-item version).36 The ACT and childhood ACT have been translated into various languages and have also been determined reliable, valid and capable of reflecting changes in control over time.37–39

The asthma therapy assessment questionnaire (ATAQ) has been validated and assesses control by evaluating seven parameters, including missed work, school, and normal daily activities; night-time sleep disturbances due to asthma symptoms; and the use of relief medications based on self-perception.30

All of these tests were found to have test-retest reliability and internal consistency, validity, responsiveness, and interpretability.30 All are relatively short, easy to interpret, and applicable to patients with different levels of disease severity and control.

ConclusionsThe desired level of asthma control has not been achieved in a considerable number of regions throughout the world. The lack of asthma control results from the disease process itself, overestimation of disease control by patients and physicians, and some social and economic factors. Low control levels increase morbidity and mortality, especially in developing countries. Providing education to physicians, especially in primary care, and to patients on what constitutes good asthma control according to the guidelines is the first step to improvement. The revised guidelines underline the significance of assessment, achievement and maintenance of control through ongoing, regular monitorisation.

Here we report that we have no potential conflicts of interest, and no financial support was received for this review.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.