The pathogenesis of chronic urticaria is incompletely understood. There is growing interest in the role of the coagulation cascade in chronic urticaria. We aimed to assess the possible activation of the coagulation cascade in chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) in relation to disease severity and activity.

MethodsThis study was conducted on 30 patients with active CSU and 30 apparently healthy individuals as controls. Patients with acute urticaria, physical urticaria, or any form of urticaria other than spontaneous urticaria were excluded. Plasma levels of D-dimer and activated factor VII (FVIIa) were measured by ELISA at baseline for all recruited patients and controls. In addition, they were measured for CSU patients after complete disease remission.

ResultsPlasma levels of D-dimer and FVIIa were significantly higher among patients with active CSU than among healthy controls. D-dimer levels were lowest among patients with grade 1 severity and highest among those with grade 4 severity. Factor VIIa levels did not differ significantly according to disease severity grades. After complete disease remission, there was a significant dramatic drop in levels of D-dimer and FVIIa among patients.

ConclusionWe conclude that activation of the coagulation cascade occurs in CSU, and we demonstrate the novel finding that activated factor VII levels are significantly reduced after medical therapy, confirming the implication of the extrinsic pathway activation in CSU. Future controlled studies may investigate the role of anticoagulant therapy in refractory chronic urticaria.

Chronic urticaria (CU) is a common disorder presenting as cutaneous wheals with or without angio-oedema for more than six weeks, occurring on a continuous or recurrent basis over prolonged periods of time and caused by release of vasoactive mediators from mast cells within the dermis.1 Urticaria can be classified into a subtype in which eliciting factors are recognisable (including physical, aquagenic, cholinergic, contact and exercise-induced urticaria), and the subtype of spontaneous urticaria in which the wheals occur without any obvious stimulus and are not triggered by eliciting factors.2

The pathogenesis of CU is poorly understood. Several factors have been advocated as causes of the disease, including emotional disorders, food allergy, intolerance to food additives and chronic infections like Helicobacter pylori.3 In 30–50% of cases, autoimmune processes have been suggested as causative factors.4 Some interleukins, such as IL-17 and IL-23, which have been detected previously in various autoimmune diseases, have been demonstrated to be significantly increased in serum of patients with CU.5 Changes in serum levels of dehydroepiandrosterone and prolactin hormones have also been demonstrated in CU patients.6,7

Evidence has accumulated for the possible involvement of the coagulation cascade in the pathogenesis of CSU. It has been demonstrated that CSU is associated with the generation of thrombin, the last enzyme of the coagulation cascade, and that the severity of the disease is paralleled by the amount of thrombin generated.8,9 Thrombin is a serine protease involved in haemostasis as well as in vessel wound healing, revascularisation, and tissue remodelling.10 Thrombin causes oedema by increasing vascular permeability and by triggering the degranulation of mast cells.11 Most effects of thrombin are histamine-mediated (and hence mast cell-mediated), as they have been reported to be reduced by antihistamines and mast cell granule depletion in animal models.12 Once thrombin is generated, it acts on fibrinogen, which is converted into fibrin. Fibrin degradation (fibrinolysis) then occurs, leading to an increase in D-dimer, a breakdown product formed by fibrin degradation.9 An increase in plasma levels of D-dimer thus indicates markedly pronounced activation of coagulation, and its absence implies that thrombosis is not occurring. Negative D-dimer assays have an important role in excluding any diagnosis of coagulation.13

In the coagulation cascade, thrombin is generated from prothrombin by activated factor X. The two pathways that initiate blood coagulation and lead to the activation of factor X are the contact (intrinsic) and the tissue factor (extrinsic) pathways. Factor VII is the first factor of the extrinsic pathway. It forms a complex with the membrane-bound tissue factor in the presence of Ca++; this complex activates primarily factor X.14

In the present study, we aimed to assess the possible activation of the coagulation cascade in chronic spontaneous urticaria, and its relation to disease severity and activity.

Materials and methodsThis case-control study was conducted on 30 patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria (male/female, 12/18; mean age, 29.57±8.76 years), and 30 apparently healthy individuals as controls (male/female, 12/18; mean age, 25.9±7.08 years). Patients were recruited from the Allergy and Dermatology outpatient clinics at Ain Shams University Hospitals, and were symptomatic with active chronic urticaria (CU) at the time of their enrolment. CU was diagnosed on the basis of the appearance of continuous or recurrent hives with or without angio-oedema for more than six weeks.15 Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) was diagnosed after exclusion of all identifiable factors.16 Patients with acute urticaria, physical urticaria, or any form of urticaria other than spontaneous urticaria were excluded. Viral, bacterial, and parasitic infections were excluded on the basis of clinical history and appropriate investigations. Skin test was performed to exclude allergic causes of urticaria. Further exclusion criteria included patients with co-morbid systemic diseases, patients on regular anticoagulant therapy, patients who had been on systemic steroid therapy within six weeks before recruitment and patients who had been receiving antihistamines within five days before recruitment. An informed consent was obtained from all study participants prior to conducting the study, and the study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Ain Shams University.

Grading of disease severityDisease severity was assessed according to the number of wheals present at the time when blood samples were collected, as follows: 1–10 small (<3cm in diameter) wheals=grade 1 (slight); 10–50 small wheals or 1–10 large wheals=grade 2 (moderate); >50 small wheals or >10 large wheals=grade 3 (severe); virtually covered with wheals=grade 4 (very severe).17

D-dimer and activated factor VII (FVIIa)Plasma levels of D-dimer and FVIIa were measured for all recruited patients and controls. In addition, they were measured for CSU patients after complete disease remission. For remission criteria, we established that patients must have been without urticarial lesions for a minimum period of four weeks and under medical treatment according to the recent standard practice guidelines.16

D-dimer assayThis was performed by ELISA (Zymutest D-dimer; Hyphen BioMed, Neuville-sur-Oise, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions. According to this kit, the expected D-dimer concentration in normal human plasma is usually <500ng/ml.

FVIIa assayThis was performed by ELISA (Zymutest Factor VII; Hyphen BioMed, Neuville-sur-Oise, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions. According to this kit, the expected Factor VIIa concentration in normal human adult plasma is usually in the range 70–130%.

Statistical analysisAnalysis of data was performed using the SPSS program, version 12. Data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD) for parametric data, and as median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-parametric data, respectively. Parametric data were analysed using Student's t-test for the comparison of two groups. Non-parametric data were analysed using the Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis tests to compare two and three groups, respectively. Mann–Whitney U test was used as a post hoc test if the Kruskal–Wallis test was significant. Chi-square test was used to analyse categorical data. To analyse non-parametric paired data, Wilcoxon signed ranks test was used. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

ResultsThe present study included 30 patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria and 30 healthy controls. Age and gender were comparable between both study groups (p=0.08, p=1.0 for age and gender, respectively). Among patients with CSU, severity grades were 1 among five patients (16.7%), 2 among 13 patients (43.3%), 3 among nine patients (30%), and 4 among three patients (10%). The mean age of onset of CSU was 25.3±7.8 years. Duration of disease ranged from 0.5 to 15 years, with a median (interquartile range) of 2.0 (1.0, 6.5) years.

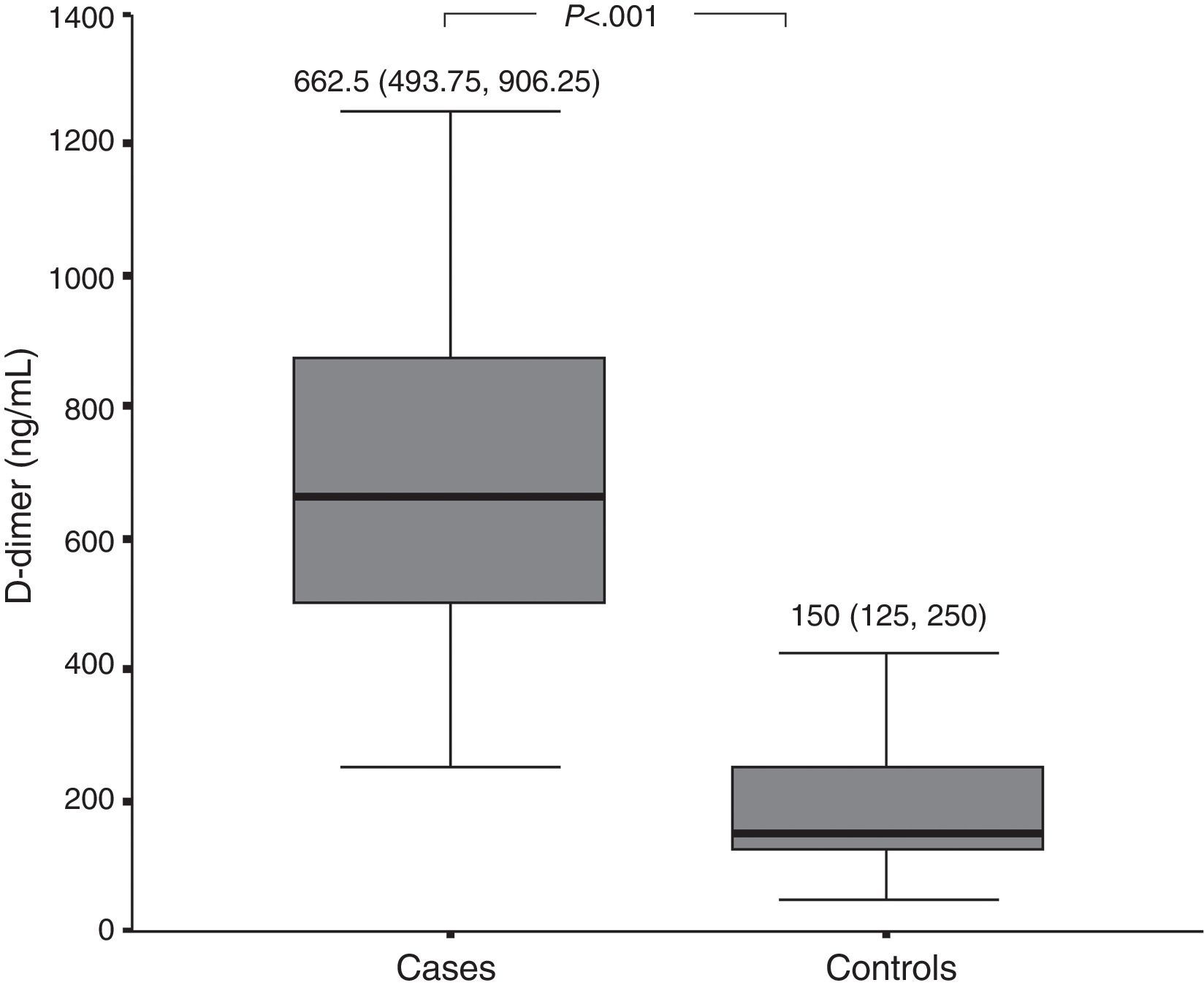

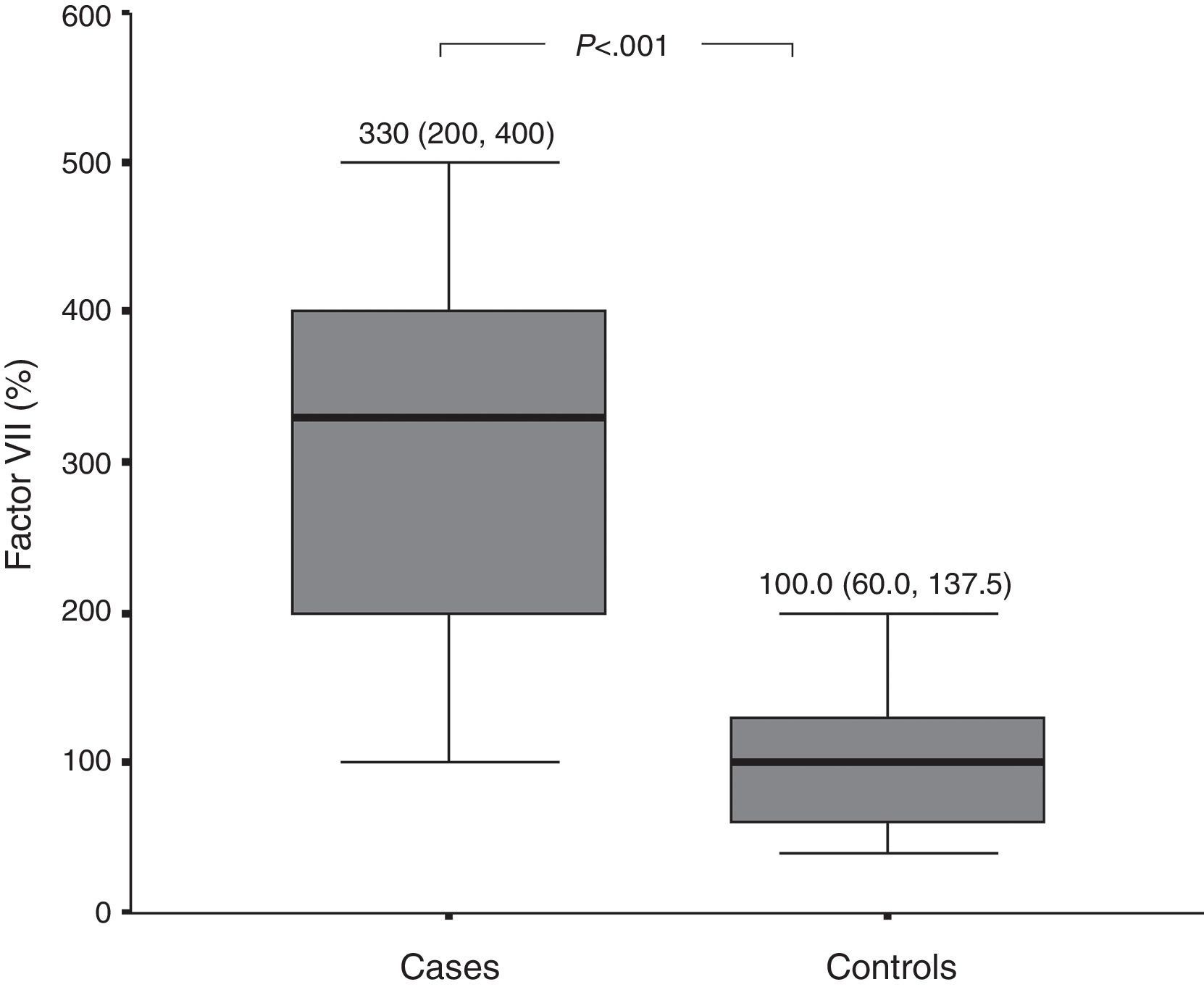

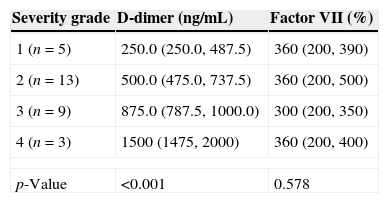

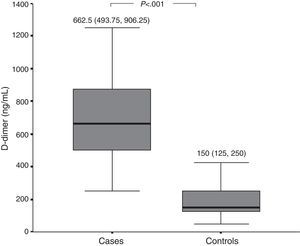

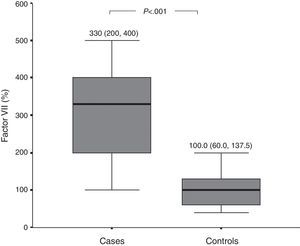

D-dimer and FVIIa at baselinePlasma levels of D-dimer and FVIIa were significantly higher among patients with active CSU than among healthy controls (Figs. 1 and 2, respectively). There was a significant difference in D-dimer levels across the different grades of disease severity among CSU patients. D-dimer levels were lowest among patients with grade 1 severity and highest among patients with grade 4 severity. On the other hand, factor VIIa levels did not differ significantly according to the different disease severity grades (Table 1).

Comparison of baseline levels of D-dimer and factor VII among patients according to the different grades of severity.

| Severity grade | D-dimer (ng/mL) | Factor VII (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (n=5) | 250.0 (250.0, 487.5) | 360 (200, 390) |

| 2 (n=13) | 500.0 (475.0, 737.5) | 360 (200, 500) |

| 3 (n=9) | 875.0 (787.5, 1000.0) | 300 (200, 350) |

| 4 (n=3) | 1500 (1475, 2000) | 360 (200, 400) |

| p-Value | <0.001 | 0.578 |

All values are presented as median (interquartile range).

D-dimer: 1 vs. 2, p=0.014; 1 vs. 3, p=0.002; 1 vs. 4, p=0.022; 2 vs. 3, p=0.001; 2 vs. 4, p=0.008; 3 vs. 4, p=0.011.

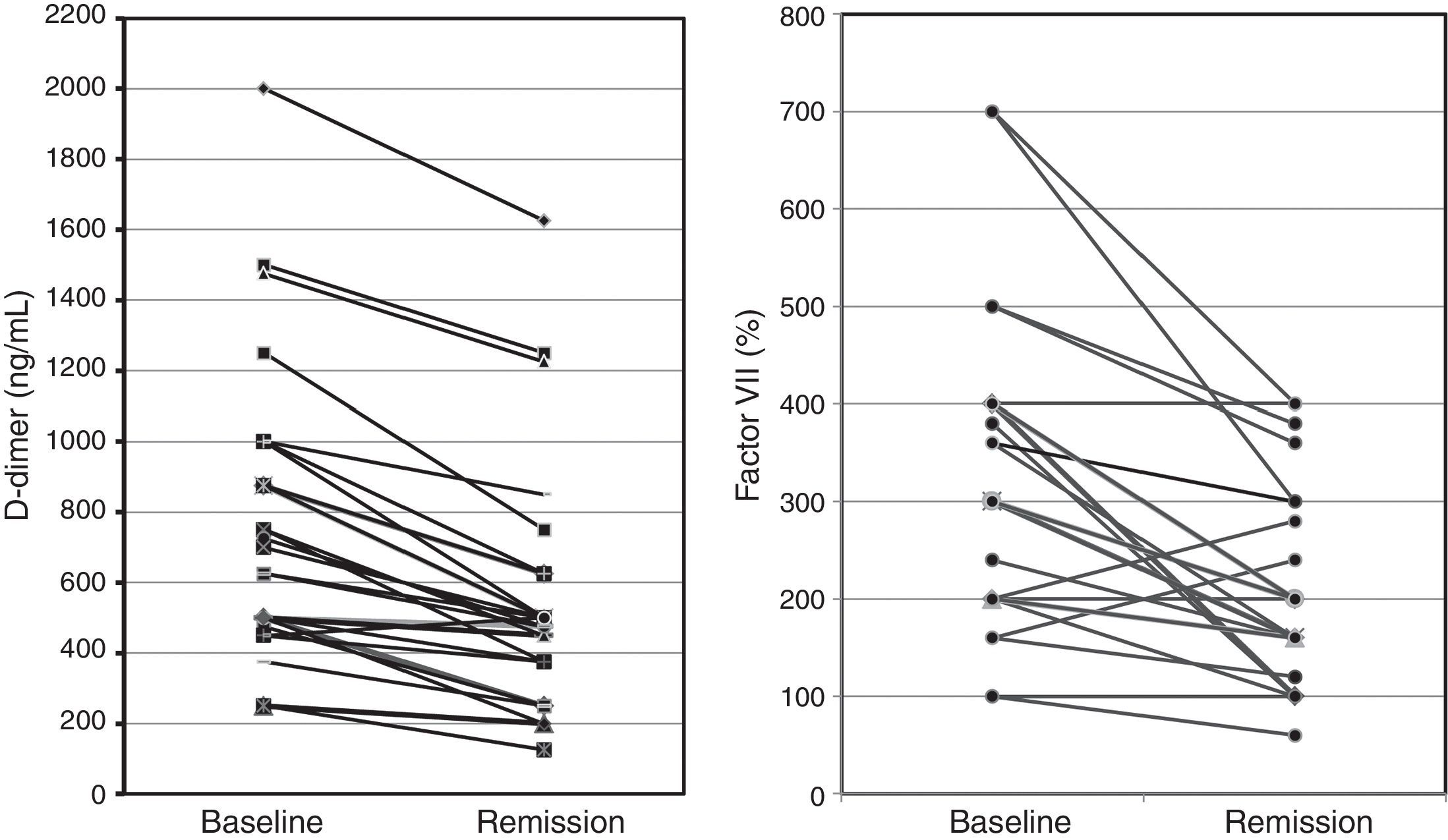

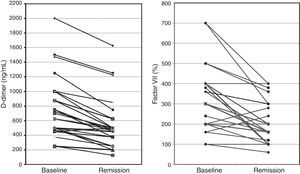

Among 25 patients who were available after remission, there was a significant dramatic drop in levels of D-dimer [median (IQR), 487.5 (343.75, 625.0)ng/mL, p<0.001], and FVIIa [median (IQR), 200 (150, 300) %, p<0.001] among patients with CSU (Fig. 3).

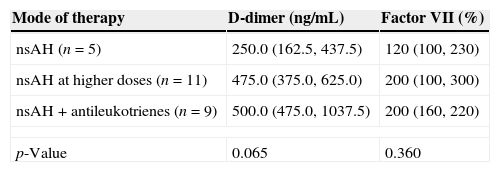

D-dimer and FVIIa according to the treatment modalityWe compared levels of D-dimer and FVIIa after complete remission between patients who required non-sedating H1-antihistamines (nsAH) only, patients who required nsAH at higher doses, and patients who required nsAH+antileukotrienes. We observed a rising trend in D-dimer levels according to the treatment modality. However, this trend did not reach statistical significance (Table 2).

Comparison of levels of D-dimer and factor VII among CSU patients after complete disease remission according to the different modes of therapy used.

| Mode of therapy | D-dimer (ng/mL) | Factor VII (%) |

|---|---|---|

| nsAH (n=5) | 250.0 (162.5, 437.5) | 120 (100, 230) |

| nsAH at higher doses (n=11) | 475.0 (375.0, 625.0) | 200 (100, 300) |

| nsAH+antileukotrienes (n=9) | 500.0 (475.0, 1037.5) | 200 (160, 220) |

| p-Value | 0.065 | 0.360 |

All values are presented as median (interquartile range); nsAH, non sedating H1-antihistamine.

In the present study, we assessed the activation of the coagulation cascade in patients with CSU. The mean age of patients was 29.6±8.8 years, which is similar to that reported in Egyptian studies on CSU (30 and 32 years),18,19 and which corresponds to the peak age of CSU in most international studies (between 20 and 40 years).16

We observed that levels of D-dimer were significantly higher among patients with CSU than among healthy controls. Furthermore, D-dimer levels were lowest among patients with mild disease and highest among patients with severe disease.

A number of investigators have demonstrated significantly higher plasma D-dimer levels in CSU patients than in controls, as well as a significant association between D-dimer levels and the severity of disease.9,18,20–22

We also evaluated the activation of the extrinsic pathway of coagulation in patients with CSU by measuring activated factor VII (FVIIa), and observed that FVIIa levels were significantly higher among patients with CSU than among healthy controls.

Few studies have investigated the possible activation of the extrinsic pathway of coagulation in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Asero et al. demonstrated an increase in plasma FVIIa but not FXIIa (a factor of the intrinsic pathway) among patients with CSU.9 A Chinese study demonstrated significantly increased levels of FVIIa and D-dimer in plasma of 30 CSU patients in comparison to 30 healthy controls. They also showed that prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (APTT) were in the normal range in CSU patients, demonstrating that although the coagulation cascade is clearly activated in CSU, thrombin generation and secondary fibrinolysis are in a dynamic balance, resulting in PT and APTT normalisation.23 Further support for activation of the extrinsic pathway of coagulation can be derived from the strong expression of tissue factor (TF), an initiator of the extrinsic pathway, by eosinophils and upper dermal inflammatory cells from urticarial skin lesions but not from normal skin.9,24 The role of eosinophils in tissue factor-expression among CSU patients is further supported by a recent study, which demonstrated that serum eotaxin, which plays a vital role in recruitment and activation of eosinophils in the skin of CU patients, was significantly higher in CSU patients than in healthy controls.25 The previous studies highlight a role for activation of the extrinsic pathway among patients with CSU. On the other hand, other investigators have observed no significant difference in levels of FVIIa between CSU patients or healthy controls.22,26

Inflammation is the link between the immune and the coagulation system. Pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin 1, interleukin 6 and tumour necrosis factor alpha, induce the expression of TF, which activates factor VII. This catalyses the activation of the TF pathway of coagulation resulting in the generation of thrombin.27 The sequence of aetiological events in CSU is still incompletely understood. It remains unclear whether the activation of coagulation and/or fibrinolysis in CSU is the primary cause of wheal formation or is the secondary result of the release of histamine and other mediators from mast cells. The former possibility is supported by findings of symptomatic improvement in CSU patients by warfarin and heparin.28,29 On the other hand, some patients with acute urticaria, idiopathic angio-oedema or inducible types of urticaria also exhibited an elevation of D-dimer levels,21 which may suggest that the activation of the coagulation cascade is a common phenomenon in urticaria and may not be specific to CSU, and therefore might be a secondary event caused by the activation of mast cells. Also in support of the latter possibility is the likelihood that endothelial cells in CSU may be activated by autoantibodies, cytokines, complement, histamine and other mast cell-derived factors; this process may be responsible for TF expression, and secondary extrinsic coagulation pathway activation and fibrinolysis.9 In line with endothelial cell activation in CSU, Puxeddu et al. have recently detected that biomarkers of endothelium dysfunction (sVCAM-1 and sICAM-1) were increased in a large number of patients with CSU, in addition to other chemokines (such as CCL5/RANTES) that contribute to the amplification of the inflammatory process during the late phase of urticaria. CCL5/RANTES is a potent chemoattractant protein for T cells, eosinophils, and monocytes, whereas adhesion molecules (sVCAM-1 and sICAM-1) play an important role in the migration of inflammatory cells to the site of inflammation.30

It is apparently contradictory that patients with CSU do not seem to be at risk for thrombotic events, despite the increased activation of the coagulation system. Activation of coagulation in inflammatory diseases without thrombotic effect suggests that the activation of coagulation components may be pathophysiologically independent of thrombus formation. The activation of the coagulation/fibrinolysis cascade may occur extravascularly in these patients after extravasation of plasma coagulation factors into the dermis, and once the cascade is activated, thrombin becomes inactivated by tissue anti-thrombin III, thus not affecting plasma anti-thrombin III activity.31

Only a few relevant studies have compared factors of coagulation/fibrinolysis in plasma of CSU patients during disease activity with their corresponding levels after remission. Asero et al. demonstrated a reduction in plasma levels of D-dimer during remission in two patients; one patient after one week of therapy; and another patient after one year, while he was not assuming any therapy.9 Two Japanese studies on CSU patients also demonstrated significant reductions in plasma D-dimer levels after disease remission.21,31

In the present study, we were able to follow up 25 of our recruited patients with active CSU till complete disease remission, and similar to the previous studies, we observed that levels of D-dimer among these patients showed a significant dramatic reduction after remission, as compared to their levels at baseline. We also report the novel finding that FVIIa levels in plasma were significantly reduced after remission. These observations confirm that activation of coagulation and fibrinolysis occurs in CSU patients due to the activation of the extrinsic pathway, and is significantly related to the activity of the disease.

The clear association between coagulation/fibrinolysis and CSU paves the way for the conduction of clinical trials with anticoagulants. Clinical trials using warfarin or heparin among CSU patients not responding to antihistamine therapy have demonstrated improvement in at least two-thirds of the studied patients.28,32,33 However, these studies were small and were conducted on fewer than 10 patients. Larger, blinded, randomised controlled clinical trials are required to evaluate the efficacy of anticoagulants in selected CSU patients who are unresponsive to antihistamine therapy.34

In the present study, a trend of rising D-dimer levels was observed in association with increasing modalities of therapy. D-dimer levels after remission were highest among patients who required antihistamines in high doses plus antileukotrienes, as compared to those who required lower doses of antihistamines. However, this trend did not reach statistical significance. This finding warrants further large-scale studies; in addition, studies are needed to assess levels of coagulation factors between responders and patients who are refractory to conventional therapy.

Our study has limitations. We did not perform autologous serum or plasma skin test (APST) to assess autoreactivity among patients with CSU. In a recent study, the coagulation cascade has been demonstrated to be activated in CU patients even with a negative APST, although to a lesser extent than in patients with CU and a positive APST. It has been suggested that activation of the coagulation system in CU occurs irrespectively of the APST status.35

In conclusion, our study results confirm that activation of coagulation and fibrinolysis occurs in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria, and is related to both the severity and activity of the disease. We demonstrate for the first time that activated factor VII, a factor of the extrinsic pathway, was significantly reduced after medical therapy, further confirming the implication of the extrinsic pathway activation in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Further large-scale controlled studies are needed to evaluate the possible role of anticoagulant therapy in severe chronic urticaria refractory to medical treatment.

Ethical disclosuresPatients’ data protectionConfidentiality of data. The authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article. An informed consent was obtained from all study participants, and the study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that no funding or grant was received for the study, and that they have no conflict of interest, financial or personal relationship related to the study.