Edited by: Andrea Gallioli

Fundació Puigvert

Marco Moschini

San Raffaele Hospital

Last update: June 2025

More infoTo evaluate the role of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) as a prognostic and predictive biomarker in the perioperative management of muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC).

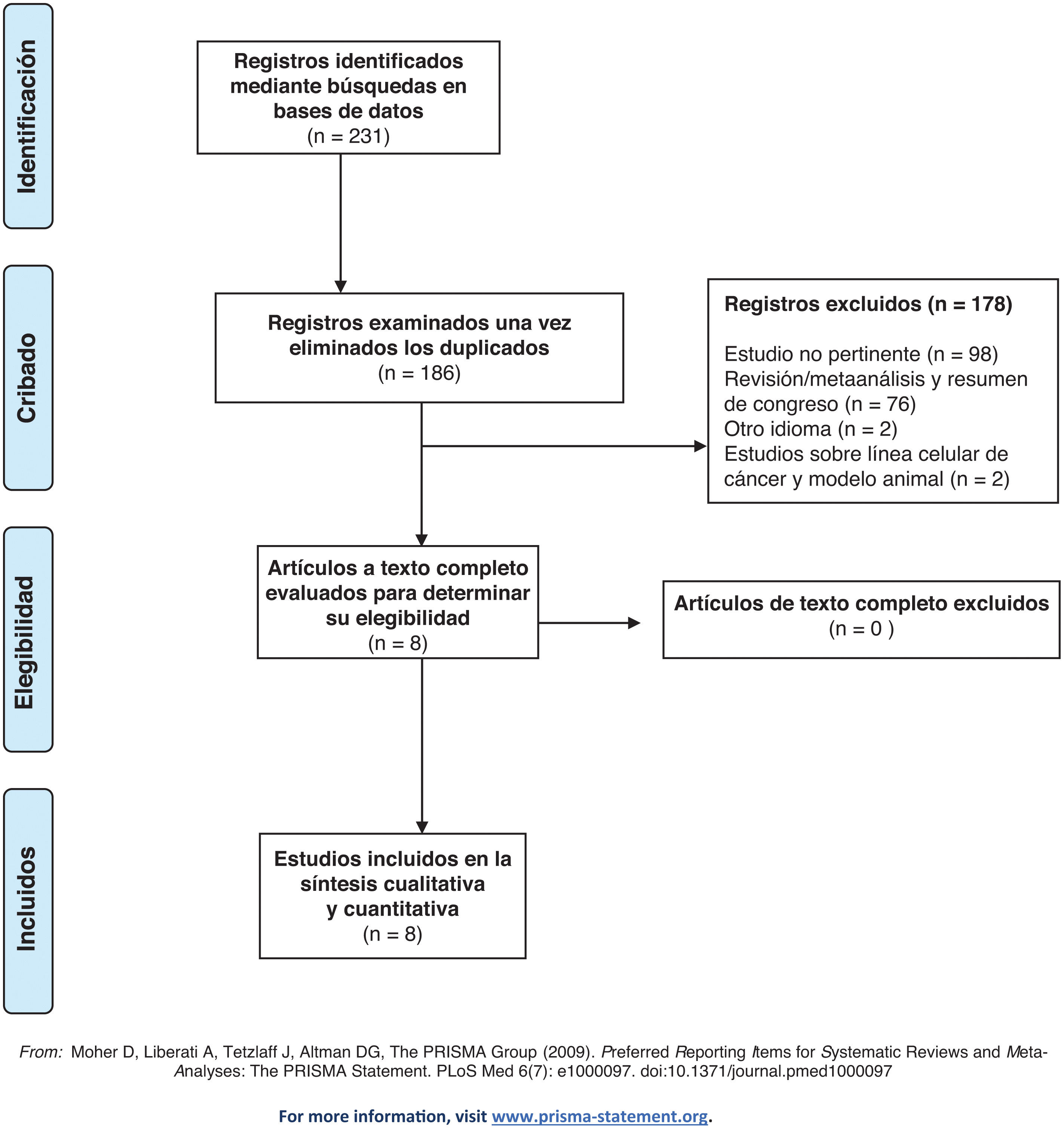

MethodsWe conducted a systematic literature review using PubMed, MEDLINE, and Embase, following PRISMA guidelines. Studies from January 2013 to March 2024 were included if they examined ctDNA in MIBC patients undergoing radical cystectomy (RC) and perioperative chemotherapy or immunotherapy.

ResultsEight studies were included. ctDNA detected before RC was associated with poor recurrence-free survival and higher risk of nodal and locally advanced disease. Postoperative ctDNA levels correlated with shorter disease-free survival and higher recurrence rates. ctDNA clearance during neoadjuvant chemotherapy was predictive of treatment response. ctDNA status post-neoadjuvant immunotherapy correlated with pathological outcomes and recurrence rates.

ConclusionsctDNA is a promising biomarker for predicting oncological outcomes in MIBC, with potential to guide perioperative treatment decisions. Further randomized controlled trials are needed to validate these findings.

Evaluar el papel del ADN tumoral circulante (ctDNA) como biomarcador pronóstico y predictivo en el tratamiento perioperatorio del cáncer de vejiga musculo invasor muscular (CVMI).

MétodosRealizamos una revisión sistemática de la literatura utilizando PubMed, MEDLINE y Embase, siguiendo las directrices PRISMA. Se incluyeron estudios publicados entre enero de 2013 y marzo de 2024 que analizaron el ctDNA en pacientes con CVMI sometidos a cistectomía radical (CR) y a inmunoterapia o quimioterapia perioperatoria.

ResultadosOcho estudios fueron incluidos en la revisión. La detección de ctDNA previa a la CR se asoció con una supervivencia libre de recurrencia baja y un mayor riesgo de enfermedad ganglionar y localmente avanzada. Los niveles de ctDNA en el postoperatorio se correlacionaron con una menor supervivencia libre de enfermedad y mayores tasas de recurrencia. La eliminación de ctDNA durante la quimioterapia neoadyuvante predijo la respuesta al tratamiento. Los niveles de ctDNA tras la inmunoterapia neoadyuvante se correlacionaron con los resultados patológicos y las tasas de recurrencia.

ConclusionesEl ctDNA es un biomarcador prometedor en la predicción de los resultados oncológicos del CVMI, y podría guiar la elección del tratamiento perioperatorio. Se necesitan más ensayos controlados aleatorizados para validar estos hallazgos.

Bladder cancer (BC) stands as the 10th most commonly diagnosed cancer globally, and as the 13th leading cause of cancer-related death. Annually, over 570.000 new cases of BC are reported worldwide, with about 25% being muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC).1 For patients eligible for cisplatin, the standard treatment for non-metastatic MIBC includes three to four cycles of cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC), followed by radical cystectomy (RC) and lymph node dissection.2,3 However, there remains a significant subset of patients for whom cisplatin is contraindicated.4,5 Whitin the adjuvant setting, platin-based chemotherapy currently represents the standard-of-care.3 Recently, nivolumab received approval in United States and European countries as adjuvant therapy post-cystectomy for all patients and for those with high-risk PD-L1 expression, respectively, due to its impact on disease-free survival (DFS).6 Identifying, patients at high-risk of recurrence following RC remains crucial in this setting despite so far histopathological findings are the only recognized elements to stratify the risk. Various tissue-based biomarkers, including urine and serum cytokines, mRNA expression profiling and DNA sequencing have been explored in urothelial carcinoma to serve as prognostic and predictive tools, aiming to improve patient selection and minimize unnecessary toxicities.7–9 In this setting, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has recently emerged as a potential biomarker for MIBC. Tumor informed ctDNA assays are highly sensitive and specific, but also require sequencing of primary tumors and reference blood to build the patient-specific assays. Moreover, it consists of a liquid biopsy, therefore it does not require any invasive procedure. Some application of ctDNA testing may not require patient-specific assays (eg, monitoring of treatment response in metastatic disease with a high tumor burden); however, for evaluating minimal residual disease (MRD) and treatment response in this setting, highly sensitive tumor informed methods are needed. Currently, ctDNA assessment is labor heavy and relies on different approaches, but all consist in evaluation at several timeframes in order to monitoring treatment response, assessing disease burden and in predicting oncological outomes.10–12 Indeed, it has shown that increased ctDNA levels indicates progression and relapse months ahead of conventional radiological methods.13–15 Recent studies have investigated the prognostic and predictive potential of ctDNA in the perioperative management of MIBC. This systematic review merged evidence on the application of ctDNA as a biomarker for prognosis and prediction in this context.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a systematic literature review utilizing the PubMed, MEDLINE, and Embase databases, adhering to the guidelines set by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement. Our search encompassed publications from January 2013 to March 2024. The primary search strategy employed the Medical Subject Headings (MESH) terms “circulating tumor DNA [Mesh]” and “urinary bladder neoplasms [Mesh]” alongside a thorough list of keywords including “ctDNA,” “bladder neoplasms,” “bladder cancer,” and “cfDNA.” We included both retrospective and prospective studies that examined the effects of NAC, adjuvant chemotherapy, and/or immunotherapy in the treatment of non-metastatic MIBC (stages T2-T4a, any N, M0) following RC. We excluded reviews, case reports, meta-analyses, and articles that were only available as abstracts or comments. The literature search initially identified 231 records. After eliminating duplicates, two independent reviewers (AAG and GC) screened the titles and abstracts (Fig. 1). The risk of bias in the non-randomized included studies was assessed using the Risk of Bias in Nonrandomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool (Table 1). Ultimately, eight studies met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review (Table 2). We reported results stratified by ctDNA status to monitor and/or predict disease status, relapse, and progression. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were presented in forest plots to illustrate the relationships between ctDNA levels and survival outcomes.

Risk of bias assessment for individual studies using the Risk of Bias in Nonrandomized controlled Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool.

| Authors | Confounding | Selection Bias | Classification of intervention | Missing data | Measurement of outcomes | Selection of the reported results | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ben-David et al.16 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Sfakianos et al.17 | Low | Intermediate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Patel et al.18 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Birkenkamp-Demtröder et al.19 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Christensen et al.20 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Carrasco et al.21 | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low |

| Szabados et al (ABACUS)22 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Powels et al (IMVIGOR 010)23 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Author (year) | Type of study | N | Setting | Systemic therapy | Methodology used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christensen et al.20 (2019) | Two centers Retrospective | 68 | NAC+RC | Cis-Gem | WES GRCh38 genome assembly RNeasy mini-kit R |

| 102 | RC | ||||

| Powles et al.23 (2021) | Prospective Randomized Open label Multicenter International Phase III | 581 | Adjuvant setting of MIBC and UTUC | Atezolizumab | WES of tumor tissue and following amplicon-based sequencing of plasma cfDNA |

| Patel et al.18 (2017) | Prospective Single arm Single center | 17 | NAC | MVAC | Combination of tagged-amplicon sequencing and shallow whole genome sequencing |

| Birkenkamp-Demtröder et al.19 (2018) | Prospective Single arm Single center | 26 | NAC | Cis-Gem | ddPCR assays targeting single nucleotide variants, or small insertions or deletions |

| Carrasco et al.21 (2022) | Prospective Single arm Single center | 37 | NAC or adjuvant chemotherapy | Cisplatin based NOS | Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA kit and ddPCR |

| Szabados et al.22 (2022) | Prospective Multicenter International Single arm Phase II | 95 | Neoadjuvant setting | Atezolizumab | WES of tumor tissue and multiplex PCR-NGS ctDNA assay |

| Ben-David et al.16 (2024) | Prospective Single center | 112 | RC+NAC RC | NA | Signatera assay (WES of the primary tumor) |

| Sfakianos et al.17 (2024) | Retrospective Multicenter | 167 | RC+NAT RC | Chemotherapy, Chemoimmunotherapy, or Immunotherapy | ctDNA test (Signatera; Natera, Austin, TX, USA) |

| Cox regression analysis |

cfDNA: cell-free DNA; Cis-Gem: cisplatin-gemcitabin; ctDNA: circulating tumor DNA; ddPCR: digital droplet polymerase chain reaction; dsDNA: double stranded DNA; MVAC: methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin; NAC: neoadjuvant chemotherapy; NGS: next-generation sequencing; NOS: not otherwise specified; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; WES: whole exome sequencing; RC: radical cistectomy; NA: not available.

In total, eight studies met the inclusion criteria and were incorporated into the analysis (Tables 2 and 3). Ben-David and coworkers assessed whether ctDNA status before RC is predictive of pathological and oncological outcomes evaluating also the dynamic changes in ctDNA status after RC in relation to recurrence-free survival (RFS).16 Overall, 112 patients were included of those 21 (29%) received neoadiuvant and 26 (23%) adjuvant treatment. ctDNA was detected before RC in 59 patients (53%) and was associated with poor RFS (log-rank P<.0001). Detectable ctDNA before RC was associated with poor outcomes regardless of clinical stage (

ctDNA predictive of response to systemic treatment.

| Study | HR | 5% CI | 95% CI | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christensen et al.20 (2019) | Before RC | 5,4 | 1,5 | 19,1 | Response to NAC at pathologic specimen |

| NAC group | Before RC | 3,4 | 1,7 | 6,8 | |

| RC group | After RC | 17,8 | 3,9 | 81,2 | |

| Powles et al.23 (2021) | Change in ctDNA (from negative to positive) after adjuvant treatment predictor of DFS | ||||

| Atezolizumab group | 0,26 | 0,12 | 0,56 |

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; RC: Radical cistectomy; NAC: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy; ctDNA: circulating tumor DNA; DFS: disease-free survival.

ctDNA predictive of DFS/RFS.

| Study | HR | 5% CI | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christensen et al.20(2019) | ||||

| NAC group | Before NAC | 15,6 | 3,5 | 69 |

| After NAC | 15,2 | 5 | 46,8 | |

| Before RC | 3,4 | NA | NA | |

| After RC | 37,7 | 8,5 | 167,1 | |

| Powles et al.23(2021) | ||||

| Observational arm | 6,19 | 4,29 | 8,9 | |

| Atezolizumab arm | 3,9 | 2,43 | 14,47 | |

| ctDNA (+) | 0,56 | 0,41 | 0,77 | |

| ctDNA (-) | 1,07 | 0,75 | 1,52 | |

| Carrasco et al.21(2022) | ||||

| ctDNA (+) | 4,199 | NA | NA | |

| Szabados et al.22(2022) | After RC | 78 | 8,64 | 707,78 |

| Ben-David et al.16(2024) | Before RC | 4,5 | 1 | 19 |

| MRD window | 9,9 | 2,6 | 37 | |

| Variant histology | 2,9 | 1,1 | 7,7 | |

| Sfakianos et al.17(2024) | ||||

| RC group | After RC (MRD window) | 115,3 | 5,21 | 18351 |

| After RC (Surveillance window) | 23,02 | 5,51 | 96,17 | |

| NAT group | Before RC | 10,61 | 1,01 | 1434 |

| After RC (MRD window) | 8,89 | 0,721 | 109,6 | |

| After RC (Surveillance window) | 4,61 | 1.21 | 17,58 | |

| Variant histology (n=46) | After RC (MRD window) | 4,93 | 1,17 | 20,77 |

| After RC (Surveillance window) | 28,3 | 3,52 | 3660 | |

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; ctDNA: circulating tumor DNA; RC: radcal citectomy; NAC: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy; NA: not available; MRD: molecular residual disease; NAT: Neoadjuvant treatment.

Similar findings emerged from a retrospective analysis of real-world data published by Sfakianos et al. where postoperative detectable ctDNA was associated with shorter disease-free survival (DFS) when compared to undetectable ctDNA (HR 6.93; P<.001). Of note, patients with undetectable ctDNA did not appear to benefit from adjuvant therapy.17

Patel et al. provided pioneering evidence on the utility of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in plasma for monitoring MRD in the context of perioperative treatment of MIBC.18 Within 17 MIBC patients receiving neoadjuvant methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin, ctDNA was tracked before, during, and after treatment and subsequent surgery using tagged amplicon sequencing (Tam-Seq) of an eight-gene patient-specific panel in tissue tumor, plasma, and urine. This study found that the presence of ctDNA prior to NAC did not predict early treatment response or prognostic outcomes, but ctDNA detection after two chemotherapy cycles correlated strongly with recurrence, showing high sensitivity (83%, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 36%–100%) and specificity (100%, 95%CI: 42%–100%).18

Two additional studies validated the prognostic value of ctDNA post-cystectomy. Birkenkamp-Demtröder et al. conducted a prospective study on 50 MIBC patients slated for four cycles of neoadjuvant cisplatin-gemcitabine (Cis-Gem) administered at three-week intervals prior to cystectomy.19 Employing tumor-specific digital droplet polymerase chain reaction assays to analyze both somatic and germline alterations, ctDNA was used to detect metastatic recurrence post-surgery and assess treatment efficacy. Post-cystectomy, ctDNA was found in plasma in 75% of patients, with 50% experiencing systemic recurrence at a median of 275 days post-surgery. Recurrence was significantly associated with higher ctDNA levels (P<.001).19

The same research group later expanded their study to a cohort of 68 patients treated with four cycles of neoadjuvant Cis-Gem followed by cystectomy using a patient-specific 16-gene next-generation sequencing (NGS) approach and evaluating the presence of ctDNA ad different timeframes.20 The presence of ctDNA at diagnosis before NAC strongly predicted RFS (HR 29.1, CI: 3.7–230.8, P=.001). Among ctDNA-positive patients, 46% experienced recurrence within 12 months, compared to only 3% among ctDNA-negative patients (P<.001). ctDNA status pre-cystectomy also prognosticated recurrence (HR 12.0, CI: 3.8–37.5, P<.001), with a 75% recurrence rate in ctDNA-positive patients compared to 11% in ctDNA-negative patients (P<.001). All ctDNA-positive patients before cystectomy had residual tumors (stage T1) and/or lymph node metastases detected at cystectomy.20 Notably, all patients with pT0 status at cystectomy were ctDNA-negative. ctDNA status post-cystectomy exhibited robust prognostic value for RFS (HR=131.3, CI: 16.6–16.993.6, P<.0001) with sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 100% (95% CI: 75.29–100), 98% (95% CI: 89.15%–99.95%), and 98.39% (95% CI: 91.34%–99.96%), respectively. Recurrence was observed in 76% (13 of 17) of ctDNA-positive patients, while none of the ctDNA-negative patients experienced recurrence. During monitoring, ctDNA positivity accurately identified all patients with metastatic relapse (100% sensitivity and 98% specificity).

More recently, Carrasco et al. evaluated ctDNA status in MIBC patients post-surgery at intervals of 1, 4, 12, and 24 months, correlating these findings with pathological outcomes.21 ctDNA was quantified using the Quant-iT Pico-Green dsDNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The study demonstrated that ctDNA status at cystectomy correlated with higher pathological stages, and cfDNA levels at four months post-surgery served as a prognostic marker for tumor progression (HR=5.290, P=.033) and cancer-specific survival (HR=4.199, P=.038).

Circulating tumor DNA and perioperative immunotherapyIn the ABACUS phase 2 trial, which evaluated atezolizumab as a neoadjuvant therapy in 40 MIBC patients, ctDNA was analyzed using Natera's Signatera assay, a multiplex PCR-NGS ctDNA assay targeting 16 clonal somatic single nucleotide variants.22 ctDNA was detected in 63% of patients before neoadjuvant treatment and in 47% after treatment. Notably, three patients who cleared ctDNA following neoadjuvant atezolizumab also achieved a pathological complete response (pCR) at surgery. Additionally, two patients with ctDNA-positive disease at baseline and after neoadjuvant atezolizumab became ctDNA-negative post-surgery and achieved a pCR. ctDNA status post-neoadjuvant treatment correlated with pathological outcomes at cystectomy, including lymph node involvement (P=.02) and T stage (P=.0005). No relapses were observed in patients who were ctDNA-negative at baseline and post-neoadjuvant therapy. Patients who were ctDNA-positive after surgery exhibited a higher recurrence rate (RFS HR=78.22, 95% CI: 8.64–707.73, P<.001).22

Atezolizumab was also assessed as adjuvant therapy in high-risk MIBC patients in the IMVIGOR010 phase 3 trial, which did not show any improvement in disease-free survival (DFS). A retrospective analysis in the biomarker-evaluable population (n=581) utilized the Natera Signatera assay to assess ctDNA, yielding significant insights.23 Post-surgery, 37% of patients were ctDNA-positive, with 116 in the atezolizumab arm and 98 in the observation arm. ctDNA detection at this stage was associated with a higher recurrence risk compared to ctDNA-negative patients (observation arm DFS HR=6.3, 95% CI: 4.45–8.92, P<.0001). Importantly, ctDNA-positive patients treated with atezolizumab had improved DFS and overall survival (DFS HR=3.36, 95% CI: 2.44–4.62). No DFS difference was found between the arms for ctDNA-negative patients. Persistent ctDNA positivity after two cycles of atezolizumab was linked to a higher risk of disease progression and recurrence compared to ctDNA-negative patients (observation arm DFS HR=8.65, 95% CI: 5.67–13.18, P<.0001).23 In the study by Christensen et al., custom NGS patient-specific panels were developed using DNA from primary tumors and leukocytes of 92 nonmetastatic MIBC patients treated with NAC followed by RC.24 Deep targeted sequencing was performed on plasma samples (n=167), urine supernatants (n=281), and urine pellets (n=114) collected pre-RC to detect MRD and evaluate treatment response. ctDNA levels correlated with tumor stage in plasma samples but varied in urine supernatants and pellets. ctDNA clearance was associated with NAC response (pathological downstaging toP<.001) but not in urine pellets (P=.23) or plasma (P=.05). Conversely, ctDNA clearance in plasma significantly correlated with RFS (P<.001), but not in urine supernatants (P=.06) or urine pellets (P=.53).24

DiscussionVarious urinary and serum biomarkers have been evaluated to determine their potential role in predicting oncological outcomes in BC.7–9,25–27 However, these studies are burdened by several biases including low sample size, heterogeneity in protocol pathways for diagnostic workup, tissue procurement for biomarker analysis and a non-negligible discrepancy in the provided results.28 Moreover, tissue testing is associated with challenges and limitations, such as inter- and intratumoral heterogeneity, dynamic changes during the treatment, risk of complications related to the procedure, and limited material availability. cTDNA has recently emerged as a novel biomarker for predictive outcomes in MIBC with consistent findings across the available studies. Our review highlights the significance of ctDNA across different settings, serving both as a prognostic marker post-cystectomy and as a potential predictor of response in the NAC and preoperative immunotherapy contexts. Specifically, ctDNA status and its dynamics have shown promising evidence for monitoring recurrences and detecting MRD, thereby anticipating radiological progression by a significant margin. Secondly, given the toxicity associated with NAC and adjuvant immunotherapy and their impact on quality of life, the identification of biomarkers to predict and monitor responses in these settings would provide substantial benefits. This would enable de-escalation strategies, reducing unnecessary toxicity for patients. Furthermore, for patients achieving a complete molecular response (ctDNA negative) following neoadjuvant treatment and confirmed by the absence of viable residual cancer post-radical cystectomy, future possibilities may include sparing them from additional aggressive treatments. This could potentially be supplemented by evaluating urine tumor DNA. The phase II/III MODERN trial (NCT 05987241) has just started patients accrual in the United States. This study will provide new insights determining whether ctDNA levels can identify patients at higher risk of disease recurrence after RC, thereby optimizing the use of postoperative immunotherapy agents such as nivolumab and relatlimab to improve survival outcomes and reduce disease progression. The IMVIGOR 011 is an important study for the field, whereby it assesses the clinical utility of ctDNA testing in the adjuvant setting of bladder cáncer.29 Patients with positive ctDNA are randomized 2:1 to 1 year of atezolizumab versus placebo and patients with negative ctDNA undergo observation with radiographic imaging every 6 months for 2 years. If the negative ctDNA patients convert to detectable ctDNA, they can then move to the randomization of atezolizumab versus placebo arm. The primary endpoint is investigator-assessed disease free survival. The analysis presented at the EAU Congress evaluated clinical outcomes in 171 high-risk MIBC patients who entered screening for IMvigor011 and remained MRD-negative during the surveillance window. The authors showed a) OS rates of 100% at 12 months and 98% at 18 months, in patients who remained serially MRD-negative; b) DFS rates of 92% at 12 months and 88% at 18 months, in patients who remained serially MRD-negative. The authors concludes that patients who remain MRD-negative on serial testing may be spared from adjuvant treatment. Whether a molecular recurrence is a new clinical disease state is being assessed in the TOMBOLA trial whereby patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer who are treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by cystectomy and have negative serial ctDNA following surgery are then treated with atezolizumab if there ctDNA becomes detectable. The primary endpoint for this trial is complete response as defined by negative ctDNA after atezolizumab in combination with normal imaging findings. Findings from this study included that 52% of patients were ctDNA+ post-RC and 75% were detected<4 months post-RC. Overall, 55% of patients met the primary endpoint of no evidence of disease and the RFS outcomes were excellent in the ctDNA-patients (HR 1.14 (95% CI 0.81–1.62). In the exploratory results of the VOLGA trial, which presented at the latest ESMO congress, event-free survival was observed in the ctDNA clearance and ctDNA negative groups compared with the ctDNA positive group. All these data, taken together, suggest that clearance of plasma ctDNA during the neoadjuvant phase may be associated with favorable outcomes and support ctDNA as a potential biomarker and may help predict treatment benefits in patients with MIBC.

Our review does have several limitations, including the limited evidence on the use of ctDNA in these settings, heterogeneity among the included studies, and variations in endpoints and time points for ctDNA analysis. Additionally, different methods for ctDNA assessment were employed. Another significant limitation is the lack of detailed information on the time to surgery post-NAC among the selected studies, which could affect the accuracy of ctDNA as a predictive biomarker in this context. Nevertheless, the integration of ctDNA into clinical practice appears to have substantial potential and may, in the future, become a pivotal factor in the decision-making process.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, the application of ctDNA in clinical trial has led to growing evidence supporting its prognostic and predictive impact on the clinical and surgical management of MIBC. Further research, particularly well-designed randomized controlled trials, is essential to validate these findings to promote ctDNA application also in everyday clinical practice.

None.