Percutaneous nephrolithotomy is an endourologic technique commonly used in the management of nephrolithiasis. However, this procedure is not complication-free. Splenic injury is exceptionally rare with a reported rate of 1% from the total case load. We present herein two cases of splenic puncture during percutaneous nephrolithotomy that illustrate two different outcomes. In the first case, the patient remained asymptomatic and was discharged on her third post-operative day after removing the nephrostomy, without any sign of hemodynamic compromise. In the second case, the patient presented with hemodynamic instability and an abdominal computed tomography scan was done that showed free fluid in the peritoneal cavity. Emergency laparotomy was performed and revealed a deep peripheral laceration (20mm×5mm in length) that required splenectomy. After a thorough review of the existing literature, we could find only 11 other instances of injury to the spleen in which treatment outcomes were reported. Patient hemodynamic status was the main factor in deciding on the type of treatment.

La nefrolitotomía percutánea es una técnica endourológica de uso común en el tratamiento de nefrolitiasis, sin embargo, este procedimiento no está libre de complicaciones. La lesión esplénica es excepcionalmente rara, con una tasa de presentación del 1% de la carga total de procedimientos. El objetivo del trabajo es describir los distintos resultados clínicos de 2 pacientes con la misma complicación y compararlos con los casos reportados en la literatura. Presentamos 2 casos de punción esplénica durante nefrolitotomía percutánea que ilustran 2 resultados diferentes. En el primer caso, el paciente permaneció asintomático y fue dado de alta en su tercer día postoperatorio después de retirar la nefrostomía, sin ningún signo de compromiso hemodinámico. En el segundo caso, el paciente presentó inestabilidad hemodinámica y se le realizó una TC abdominal que mostró líquido libre en la cavidad peritoneal, por lo que fue necesario una laparotomía de urgencia donde se encontró una laceración profunda periférica en bazo (20×5mm) que requirió esplenectomía. Después de una revisión exhaustiva de la literatura existente, solo pudimos encontrar otros 11 casos de lesiones de bazo que informaron los resultados del tratamiento, siendo el estado hemodinámico del paciente el principal factor para decidir el tratamiento.

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) is an endourologic technique commonly used in the management of nephrolithiasis. However, this procedure is not complication-free1 and the majority of complications are related to the percutaneous access phase (about 83%).2

Injury to the intraperitoneal organs during PCNL is rarely encountered, but can be a devastating and potentially life-threatening complication with severe morbidity, given that numerous viscera lie within the path of the intended percutaneous access tract. Injury to the hollow viscera, such as the colon, can occur in 0.2–1% of patients undergoing percutaneous access. Nevertheless, splenic injury is exceptionally rare, with a reported rate of 1% of cases. Because it is very uncommon,3 the accepted management for this complication is controversial and either conservative management or splenectomy are currently the mainstay treatment options. We present two cases of splenic puncture during PCNL that illustrate two completely different outcomes.

Case 1A 60-year-old woman presented with a 24mm kidney stone (1000HU) located in the renal pelvis that was incidentally diagnosed through a computed tomography (CT) scan. In the prone position, a tract through the eleventh intercostal space was made under fluoroscopic guidance, dilating the balloon to 30Fr. No incidents were observed during the procedure.

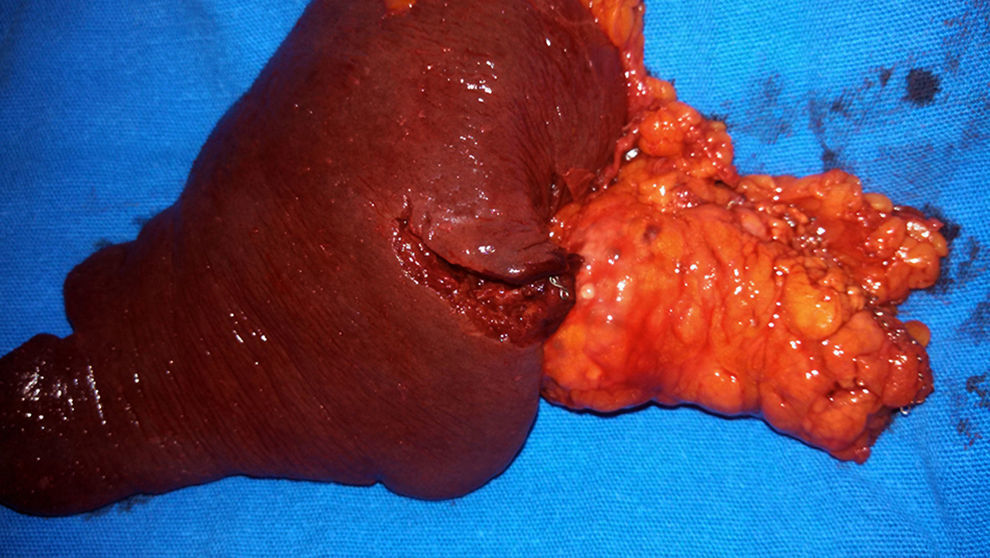

On postoperative day 1, the patient remained asymptomatic. A control CT scan showed the nephrostomy tube traversing the lower third of the spleen (Fig. 1). The patient's hemoglobin level dropped from a preoperative level of 12.6g/dl to postoperative 9.9g/dl, with no need for transfusion. The patient was discharged on her third post-operative day after removing the nephrostomy tube, without any sign of hemodynamic compromise.

Case 2An 81-year-old woman underwent PCNL after finding a stone (20mm) (1400HU) located in the left ureteropelvic junction. In the prone position, a tract through the 11th intercostal space was made under fluoroscopic guidance, dilating the balloon to 30Fr. No incidents were observed during the procedure.

After arriving at the post-anesthesia care unit, the patient developed significant hypotension, diaphoresis, and muffled respiratory sounds in the left hemi-thorax. She responded to initial i.v. crystalloid infusion. Complete blood count reported hemoglobin of 7g/dl. A chest X-ray was done that revealed left hemothorax. A pleural catheter was placed that drained 600cc of blood and transfusion was begun.

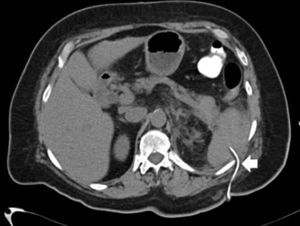

Due to the patient's rapid symptom presentation, the tract location and the amount of fluid needed for resuscitation. An abdominal CT scan was performed (Fig. 2) to rule out additional sources of blood loss. It showed free fluid in the peritoneal cavity and a trans-splenic nephrostomy tract. Emergency laparotomy was then performed that revealed a deep peripheral laceration (20mm×5mm in length) that required splenectomy (Fig. 3).

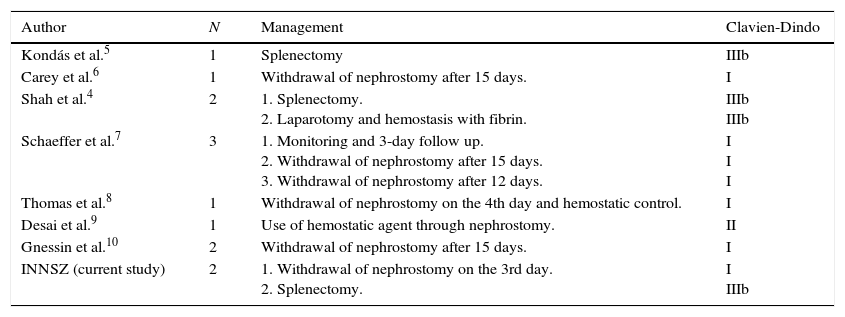

PCNL is considered the standard surgical treatment for large-volume urolithiasis. However, the anatomic location of the kidney and its relation to neighboring organs in the abdominal cavity, such as the colon, duodenum, liver, and spleen result in a potential source of iatrogenic injury to those organs. Splenic lesions have been reported as an anecdotal complication in large case series.4 The current prevalence at our hospital center is 0.87% from a total of 230 procedures. After a thorough review of the existing literature, we could find only 11 other instances of splenic injury and treatment results are shown in Table 1.4–10

Case reports in the literature review.

| Author | N | Management | Clavien-Dindo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kondás et al.5 | 1 | Splenectomy | IIIb |

| Carey et al.6 | 1 | Withdrawal of nephrostomy after 15 days. | I |

| Shah et al.4 | 2 | 1. Splenectomy. 2. Laparotomy and hemostasis with fibrin. | IIIb IIIb |

| Schaeffer et al.7 | 3 | 1. Monitoring and 3-day follow up. 2. Withdrawal of nephrostomy after 15 days. 3. Withdrawal of nephrostomy after 12 days. | I I I |

| Thomas et al.8 | 1 | Withdrawal of nephrostomy on the 4th day and hemostatic control. | I |

| Desai et al.9 | 1 | Use of hemostatic agent through nephrostomy. | II |

| Gnessin et al.10 | 2 | Withdrawal of nephrostomy after 15 days. | I |

| INNSZ (current study) | 2 | 1. Withdrawal of nephrostomy on the 3rd day. 2. Splenectomy. | I IIIb |

However, the true number of splenic punctures may be under-reported, due to the fact that not all centers perform post-PCNL CT scan and some patients may be asymptomatic.

The multiple risk factors that predispose to splenic injury during this procedure described so far include the intercostal approach, puncture site, and anatomic variations, such as a retrorenal spleen.

Splenomegaly is considered a relative contraindication for a left percutaneous nephrolithotomy because of the increased risk for splenic puncture. There is a diverse array of strategies for preventing splenic injury during puncture, but shifting the puncture site to a lateral approach may increase the possibility of colon and liver injury, and a mid-scapular approach can increase the risk for lung-related injuries.11,12

According to Hopper and Yakes, the respiratory cycle is crucial for the initial puncture. A decreased risk for splenic injury has been found when the puncture is made through the eleventh intercostal space while the patient is in deep exhalation. This risk is increased by 33% when the puncture is made through the 10th intercostal space, and is even greater during inhalation.13

There are no conclusive data about the risk for splenic injury associated with the prone vs. supine positions. The CROES study of 1311 patients found intraoperative organ perforation rates of 6% and 4.5% in the supine and prone positions, respectively, but there was no statistical significance (p=0.142).14 In the results of the study by Yacizi et al., supine positioning did not increase the risk for splanchnic injury in lower, middle, or upper calyceal accesses. However, they found that lower pole accesses have the longest puncture-to-organ distance in the supine position.15

Conservative and surgical treatment are the 2 management possibilities for trans-splenic puncture and hemodynamic status is the driving factor in selecting either of the treatment options.16 A literature review revealed that a majority of patients may be good candidates for non-surgical treatment, since only 33.3% of the cases were managed with laparotomy and/or splenectomy.

We hypothesize that the different outcomes of our two cases described herein may be a result of the site of injury in the spleen. The injury in the first case was on the periphery, but there was a sufficient amount of parenchyma surrounding the access sheath and the nephrostomy catheter, allowing for effective hemostasis. In the second case, the injury was too peripheral for the nephrostomy catheter to sufficiently compress the lacerated vessels, resulting in abundant bleeding.

Angiography with embolization has increased the possibility of non-operative treatment for patients that required surgery in the past (patients with blunt splenic injuries).17 However, we could not locate any reports on this type of management after penetrating splenic injury. Further investigation as to the value of this approach is warranted.

ConclusionSplenic injury after PCNL is a very infrequent complication and occurred in 0.87% of the patients in our case series. Management was dictated by the hemodynamic status of the patient, suggesting that tailored treatment can avoid unnecessary surgical interventions.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of people and animalsThe authors state that for this investigation have not been performed experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingNo funding of any kind was received to undertake this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest and received no sponsorship for the study.