The Hereditary Colorectal Cancer registry is one of the oldest and largest registries of its kind. It cares for patients with all hereditary syndromes of colorectal cancer using the three basic approaches of patient care, education and research. This article summarizes the structure and function of the registry, and gives examples of its contributions to the management of affected patients.

ACTIVITYIn 2016 the registry served over 1000 families with FAP, 224 families with Lynch syndrome, 61 with MYH associated polyposis and 146 with one of the hamartomatous polyposes. In 2016 there were 1009 patient visits with 80 new patients and 879 endoscopies. Over 60 surgeries were performed.

SUMMARYthe Cleveland Clinic approach to hereditary colorectal cancer is described. This is multidisciplinary, involving several specialties and both genetic counseling and mental health services within the registry.

Registries have a very important role in the management of patients and families with syndromes of hereditary colorectal cancer. They literally save lives through effective surveillance and expert clinical care 1,2. Patients with these syndromes deserve to be cared for at a registry, or at least by experts with experience and expertise in the management of these syndromes.

The Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Registry at the Cleveland Clinic began in 1979, when Dr. David G. Jagelman established a registry for patients and families with Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP). In the subsequent 38 years the registry has grown to become the largest single institution Hereditary Colorectal Cancer registry in the world. Making use of the high number of patients and families, the Clinic registry has been a leader in developing clinical practice guidelines for managing patients with hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes. During its existence, the Registry has undergone many changes; in knowledge, technology and personnel. In 1988 Dr. Jagelman moved to the new Cleveland Clinic satellite hospital in Florida. Dr Church took over direction of the registry when he arrived at the Clinic in 1989. In 2017 the leadership was transferred to another colorectal surgeon, Dr Matthew Kalady. Over the years the genotypes of most of the major syndromes of hereditary colorectal cancer have been discovered. While some syndromes remain a puzzle, we are now able to offer genetic testing to families with suggestive phenotypes. The technology of DNA sequencing has changed, leading to the introduction of Next Generation Sequencing 3. This allows Multigene Panel Testing, using large panels of genes that cover all the known syndromes and some peripheral genes as well. Multigene Panels are quicker and cheaper than the old single gene Sanger sequencing, and can lead to surprising results. This has heightened the need for genetic counseling and for an understanding of the biology of colorectal carcinogenesis. There are at least 10 known hereditary syndromes of colorectal cancer, where we can offer genetic testing and sound clinical management. Because these syndromes are rare, multigenerational and familial, and because affected patients need complex multidisciplinary care for life, a central repository of information is essential so that care can be organized. This central repository of information is the registry.

DEFINITIONIn simple terms a registry is a list; in the medical world this is often a list of patients. A Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Registry is a list of names; names of patients with a hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome and the names of their relatives. Other facts about these patients and relatives can be stored to facilitate clinical care, to allow education of the families, and to enable clinical research. As information technology advances, databases have been designed for use in this setting. The Cleveland Clinic designed its own database, Cologene™, for use as a translational tool to store family pedigrees as well as clinical information, and to use the information to generate patient appointments letters and to perform research. The database is in use at several Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Centers around the world.

STRUCTUREMost Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Registries arise around one or two key individuals, with special interest and expertise in the area. The St Marks Polyposis Registry, the original registry founded in 1929, arose around the surgical skills of John Percy Lockhart-Mummery and the pathology expertise of Cuthbert Dukes 4. The Johns Hopkins Registry was founded in 1973 by Victor McKusick, the “father” of American Medical genetics and the Creighton Registry in Omaha, Nebraska by a medical oncologist named Henry Lynch. There is evidence of the founder in many registries and there is usually a special expertise or interest, such as surgery, or medical genetics, or gastroenterology. In 2004 we surveyed all the 18 registries for Hereditary Colorectal Cancer in the USA, and described a wide range of definitions and methods. The most striking finding was the small number of registries available to the potentially large number of affected patients and families. The effects of this lack of registries can be seen in the unfortunate outcomes of treatments performed by those with little experience. In Cleveland the registry was based on the interest of David Jagelman, a colorectal surgeon who had trained at St. Marks Hospital and had noticed the benefits of the registry there. The Cleveland registry was therefore centered on colorectal surgical expertise, but over the years expert Gastroenterology, Pathology, Genetics, General Surgery, Endocrinology, Urology, Psychology, and Gynecology services have been added.

A Registry therefore starts with an interested clinician who sets about organizing a registry coordinator. The Coordinator is the “go between” between patients/families and the registry staff. A Coordinator receives referrals, gathers records, arranges appointments, and is the contact between the registry and the patient/family. Registries need a database, an office, and some organizational support. Above all, they need funding. Registries can run on a tight budget but some support needs to come from the host institution. Registries generate income by attracting referrals, seeing patients and families on a regular basis, and need appointments for their patients with multiple specialties. To this extent they generate their own support. The current structure of the Cleveland Clinic Registry is shown in Figure 1. Because of the large number of patients and families the syndromes are divided into those involving polyposis and those without polyposis. The “Florida branch “of the Registry shares the Cologene database but patients are identified according to Institution so that duplicate records are not created.

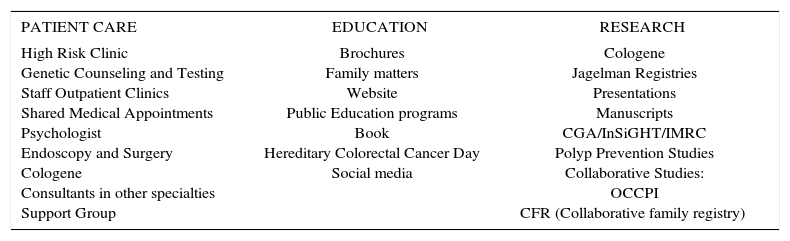

PROCESSThe mission of the Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Registry at the Cleveland Clinic is to prevent death from syndrome- related cancer while maintaining quality of life. The essence of fulfilling this mission is excellence in patient care. This involves timely and accurate diagnosis, effective surveillance, and appropriate endoscopy and surgery. In addition to patient care, the fulfillment of the mission involves education of patients, families and healthcare providers, and the performance of relevant research. These three components of the registry process are detailed in table 1.

ACTIVITIES OF THE SANFORD R. WEISS MD CENTER FOR HEREDITARY COLORECTAL NEOPLASIA.

| PATIENT CARE | EDUCATION | RESEARCH |

|---|---|---|

| High Risk Clinic Genetic Counseling and Testing Staff Outpatient Clinics Shared Medical Appointments Psychologist Endoscopy and Surgery Cologene Consultants in other specialties Support Group | Brochures Family matters Website Public Education programs Book Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Day Social media | Cologene Jagelman Registries Presentations Manuscripts CGA/InSiGHT/IMRC Polyp Prevention Studies Collaborative Studies: OCCPI CFR (Collaborative family registry) |

Referrals to the registry are usually received by a coordinator. Records are sought and received and assessed to determine the likely syndrome that applies to the patient, the medical and genetic testing that has been done, and the likely schedule that will have to be set up for the clinic visit. New patients are usually seen in a “High Risk” clinic, where consultations, endoscopies and other tests are scheduled on the same day to facilitate the patient visit. At minimum patients see either a colorectal surgeon, a gastroenterologist, or both, as well as a genetic counselor. If genetic testing is needed and agreed to then it is arranged. Patients are provided with information about the syndromes that are likely and after informed consent has been obtained are enrolled into the registry. A full family tree is drawn and the data entered into Cologene. At risk relatives need to be contacted and the proband is asked to do this, often using letters that have been provided by the registry. Surgeries or endoscopies are arranged and performed.

A recent development in the registry is the inception of shared medical appointments, where groups of patients with the same syndrome can receive both individualized care and a general information session about their syndrome. It is an efficient way of managing referrals.

During the initial intake patients and families are assessed to see if they need social/financial/psychological help. Resources are available to help with necessary uncovered services, with work-related papers and with mental health symptoms.

Much of the Registry activity is surveillance. This happens after patients have had risk-reducing surgery or endoscopy. Recommendations are given for continued surveillance, the organs and the intervals dependent on genotype and both personal and family phenotype. Once surveillance programs are established they are entered into Cologene which sends automatic prompt letters to remind patients of an upcoming appointment.

EDUCATIONAs shown in table 1, education of patients, families and healthcare providers is an important role for the registry. Our practice is to provide the necessary specialized care and then return to patient and family to their local physicians. However both the family and the caregivers need to be educated about the syndrome. To this end we produce brochures and a newsletter, and maintain a web site with links to resources. A Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Day provides the patients and their families with opportunities to meet less formally with Registry staff and to interact with them more fully. Social media is increasingly used by patients to compare experiences and to set up support groups. Involvement with this is part of the registry process.

RESEARCHResearch is a registry response to the complexity of hereditary colorectal cancer and the opportunity that large numbers of affected patients and families presents. Cologene is the hub of the research effort as the registry addresses clinical questions important to patients and caregivers. Because of the rarity of the syndromes, collaborative research is often necessary. Sometimes this is organized through the collaborative groups that exist and of which the Cleveland Clinic registry is an integral part. There are the Collaborative Group of the Americas for Inherited Colorectal cancer (CGA), and the International Society for Gastrointestinal Hereditary Tumors (InSiGHT). The registry is also involved in prospective studies of chemoprevention and is a resource for other institutions who may need extra patients to add to their studies.

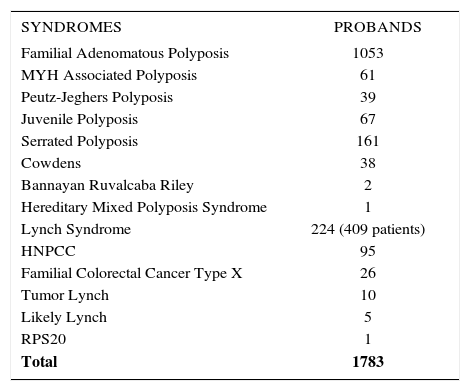

PATIENT ACTIVITYThe numbers of probands with the different syndromes as of 2016 is shown in Table 2. Outpatient activity for 2017 is shown in Table 3. These numbers reflect a steady increase in new patients and new families being referred to the Registry. These are often complex presentations and sometimes involve trying to salvage unfortunate situations that have occurred as a result of care performed elsewhere. The Cleveland Clinic registry has special interest in desmoid disease, and has a specific registry for such patients. The Cleveland Clinic registry also features advanced surgery and endoscopy techniques including minimally invasive and robotic surgery, pancreas-sparing duodenectomy, and endoscopic mucosal resection.

NUMBERS OF PROBANDS WITH HEREDITARY COLORECTAL CANCER SYNDROMES AS OF DECEMBER 2016.

| SYNDROMES | PROBANDS |

|---|---|

| Familial Adenomatous Polyposis | 1053 |

| MYH Associated Polyposis | 61 |

| Peutz-Jeghers Polyposis | 39 |

| Juvenile Polyposis | 67 |

| Serrated Polyposis | 161 |

| Cowdens | 38 |

| Bannayan Ruvalcaba Riley | 2 |

| Hereditary Mixed Polyposis Syndrome | 1 |

| Lynch Syndrome | 224 (409 patients) |

| HNPCC | 95 |

| Familial Colorectal Cancer Type X | 26 |

| Tumor Lynch | 10 |

| Likely Lynch | 5 |

| RPS20 | 1 |

| Total | 1783 |

HNPCC = hereditary non polyposis colorectal cancer (defined as a family fitting Amsterdam I or II criteria)

Tumor Lynch = microsatellite unstable high colorectal tumor or lacking expression of a mismatch repair gene on immunohistochemistry, but no germline mutation and without Amsterdam compliant family history

Likely Lynch= microsatellite unstable high colorectal tumor or lacking expression of a mismatch repair gene on immunohistochemistry, but no germline mutation, but with an Amsterdam compliant family history

There is no doubt that the Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Registry at the Cleveland Clinic has flourished since its inception in 1979. Due to the Institutional support, the excellence of the Registry Coordinators and the hard work and dedication of the Physicians, the reputation of the registry is second to none. The number of probands speaks for itself. The registry has produced well over 100 articles in the literature and at least one book on Molecular Genetics of Colorectal Cancer 6. Each of the Registry physicians has been President of the CGA, an organization that the Registry played a key role in founding. In 2003 the Registry hosted the joint meeting of the Leeds Castle Polyposis Group and the International Collaborative Group on HNPCC, while the CGA has met here in 1997 and 2008. The Registry bibliography shows key contributions in desmoid disease 7–18, upper GI polyps in FAP 19–23, colorectal surgery in FAP 24–39, prophylactic surgery in Lynch Syndrome 40–42, thyroid disease in FAP and MAP 43–45, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia in juvenile polyposis (JPS) 46, surgery in JPS and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome 47–49, the colorectal phenotype of Cowdens disease 50, and the rare syndrome of Hereditary Mixed Polyposis 51. Review papers have tried to enhance understanding within the medical community of new syndromes and advances in genetic testing technology 52–59, and the Registry has been represented in several guideline articles 60–62. The registry has served as a model for other institutions that wish to start their own. This is an important role for an established registry and one that we encourage.

THE FUTUREHereditary colorectal cancer syndromes are here to stay. They account for about 5% of all colorectal cancers and are important for the opportunity they give to intervene in high risk families and save lives. They are also important for the lessons they teach in the biology and the management of sporadic colorectal cancer. The field is becoming increasingly complex, as the advancing front of knowledge discovers new molecular perturbations that result in hereditary predisposition to colorectal cancer. Clinically more effort is needed to design patient specific treatments rather than syndrome specific treatments. The quality of surveillance must continue to improve and the importance of quality of life cannot be over-emphasized. The mental health ramifications of these syndromes is poorly understood and a major effort is needed to provide the assessment and treatment that patients deserve. All of this will be accomplished through registries, but for this to happen new, enthusiastic physicians and counselors are needed to continue the effort.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest, in relation to this article.