Symbiotic interactions with fungal endophytes are argued to be responsible for the tolerance of plants to some stresses and for their adaptation to natural conditions.

AimsIn this study we aimed to examine the endophytic fungal diversity associated with roots of date palms growing in coastal dune systems, and to screen this collection of endophytes for potential use as biocontrol agents, for antagonistic activity and mycoparasitism, and as producers of antifungal compounds with potential efficacy against root diseases of date palm.

MethodsRoots of nine individual date palms growing in three coastal locations in the South-East of Spain (Guardamar, El Carabassí, and San Juan) were selected to isolate endophytic fungi. Isolates were identified on the basis of morphological and/or molecular characters.

ResultsFive hundred and fifty two endophytic fungi were isolated and assigned to thirty morphological taxa or molecular operational taxonomic units. Most isolates belonged to Ascomycota, and the dominant order was Hypocreales. Fusarium and Clonostachys were the most frequently isolated genera and were present at all sampling sites. Comparisons of the endophytic diversity with previous studies, and their importance in the management of the date palm crops are discussed.

ConclusionsThis is the first study on the diversity of endophytic fungi associated with roots of date palm. The isolates obtained might constitute a source of biological control agents and biofertilizers for use in crops of this plant.

Se ha propuesto que la simbiosis con hongos endófitos puede ser responsable de la tolerancia de las plantas a algunas situaciones de estrés ambiental y de su adaptación a las condiciones naturales.

ObjetivosEste estudio tiene como objetivo analizar la diversidad de hongos endófitos asociados con las raíces de palmeras datileras que crecen en sistemas de dunas costeras. La finalidad es la evaluación de un grupo de cepas fúngicas para su uso como agentes de control biológico por su actividad antagónica o micoparasitaria, o como productores de compuestos antifúngicos con potencial aplicación frente a enfermedades radiculares de la palmera datilera.

MétodosSe muestrearon raíces de 9 palmeras que crecían en 3 localidades costeras en el Sudeste de España (Guardamar, El Carabassí y San Juan), y se aislaron sus hongos endófitos asociados. Las cepas se identificaron mediante el estudio de caracteres morfológicos y/o moleculares.

ResultadosSe aislaron 552 hongos endófitos, que se clasificaron en 30 taxones morfológicos o unidades taxonómicas operativas moleculares. La mayoría de las cepas pertenecen a la división Ascomycota; el orden dominante fue Hypocreales. Los géneros aislados con más frecuencia fueron Fusarium y Clonostachys, que estuvieron presentes en todos los sitios de muestreo. Nuestros resultados de diversidad hongos endófitos se comparan con los de otros estudios previos, y se discute su importancia para el tratamiento de cultivos de palmera datilera.

ConclusionesEste es el primer estudio sobre la diversidad fúngica endofíticamente asociada con raíces de palmera datilera. Las cepas obtenidas son una fuente potencial de agentes de control biológico o biofertilizantes para la aplicación en cultivos de esta planta.

Endophytes colonize the tissues of living plants without causing symptoms.24 They have been shown to protect plants from abiotic and biotic stresses17,19 and to promote plant growth.15 Fungal endophytes associated with roots of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) are a potential source of biocontrol agents of root-pathogens of this crop. Little work has been done on date palm endophytes.6–9,23 In this study, we focus on the biodiversity of endophytic fungi associated with roots of date palms growing in coastal dune systems, under conditions imposing drought and water stress. These soils are characterized by ecological factors that differ from those of large date palm plantations. Previous studies have shown that roots of plants in similar conditions harbor a large endophytic diversity.12 Moreover, coastal plants can develop symbioses with endophytes that might enhance their tolerance to stress.17 Therefore, the use of endophytes in bioremediation strategies could be valuable in arid ecosystems.4,11 The aim of this work was to isolate and characterize endophytic fungi from date palm roots in order to generate a collection of strains for future screenings for biocontrol agents and production of antifungal compounds, with potential application against root diseases of date palm.

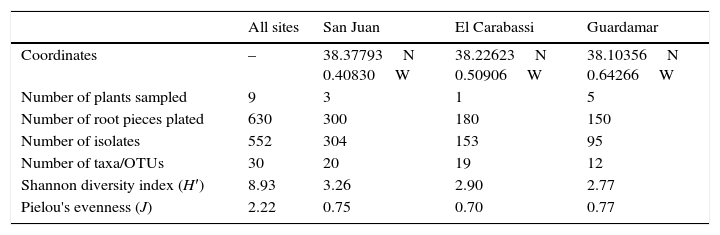

Root samples were collected from healthy date palms growing in sand dunes at three coastal locations in Alicante Province, SE Spain: San Juan, El Carabassí, and Guardamar (Table 1). Availability and irregular dispersion of date palms in this location was the cause of our choice of the samples. We collected root samples from nine plants (1.5–5m tall), consisting of 15-cm-long fragments at a depth of 20–40cm. Root samples were surface-sterilized, cut into pieces (Table 1), and plated in a culture medium for the isolation of fungal endophytes, following previously described procedures.13 Young individual fungal colonies were sub-cultured onto potato dextrose agar (PDA, Oxoid, Hampshire, UK), and stored in the culture collection of the Laboratory of Plant Pathology at the University of Alicante (Spain). These pure fungal cultures on PDA were grouped into morphotypes according to their macroscopic and microscopic features. Cultures that developed reproductive structures were identified to genus or species level with aid of literature describing their phenotypic characteristics. Thirty nine isolates that could not be identified morphologically, were selected and processed for further molecular characterization, via sequencing of their rDNA internal transcribed spacer regions (ITS) according to the protocol described by Abdullah et al.,1 and were assigned GenBank accessions KP006331–KP006369. These strains were grouped into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) according to ITS sequence similarity of 97%, and assigned to taxa as described by Maciá-Vicente et al.13 Molecular classifications were further assessed by means of phylogenetic analyses (Supplementary Fig. S1). The remaining isolates that were not sequenced were grouped in taxa according to their morphological characters. Isolation data were compared across sampling locations using analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by the Tukey Honest Significance Difference test for multiple comparisons. The diversity indicators Shannon index (H′) and Pielou's evenness index (J) were calculated for the three locations. Similarity in OTU and taxa composition of fungal communities among locations was calculated using the Jaccard index. Comparison of the occurrence of dominant fungi across locations was performed using the χ2 test, based on the counts of isolates at each site.

Characteristics of sampling sites and diversity of date palm root endophytes.

| All sites | San Juan | El Carabassi | Guardamar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coordinates | – | 38.37793N 0.40830W | 38.22623N 0.50906W | 38.10356N 0.64266W |

| Number of plants sampled | 9 | 3 | 1 | 5 |

| Number of root pieces plated | 630 | 300 | 180 | 150 |

| Number of isolates | 552 | 304 | 153 | 95 |

| Number of taxa/OTUs | 30 | 20 | 19 | 12 |

| Shannon diversity index (H′) | 8.93 | 3.26 | 2.90 | 2.77 |

| Pielou's evenness (J) | 2.22 | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.77 |

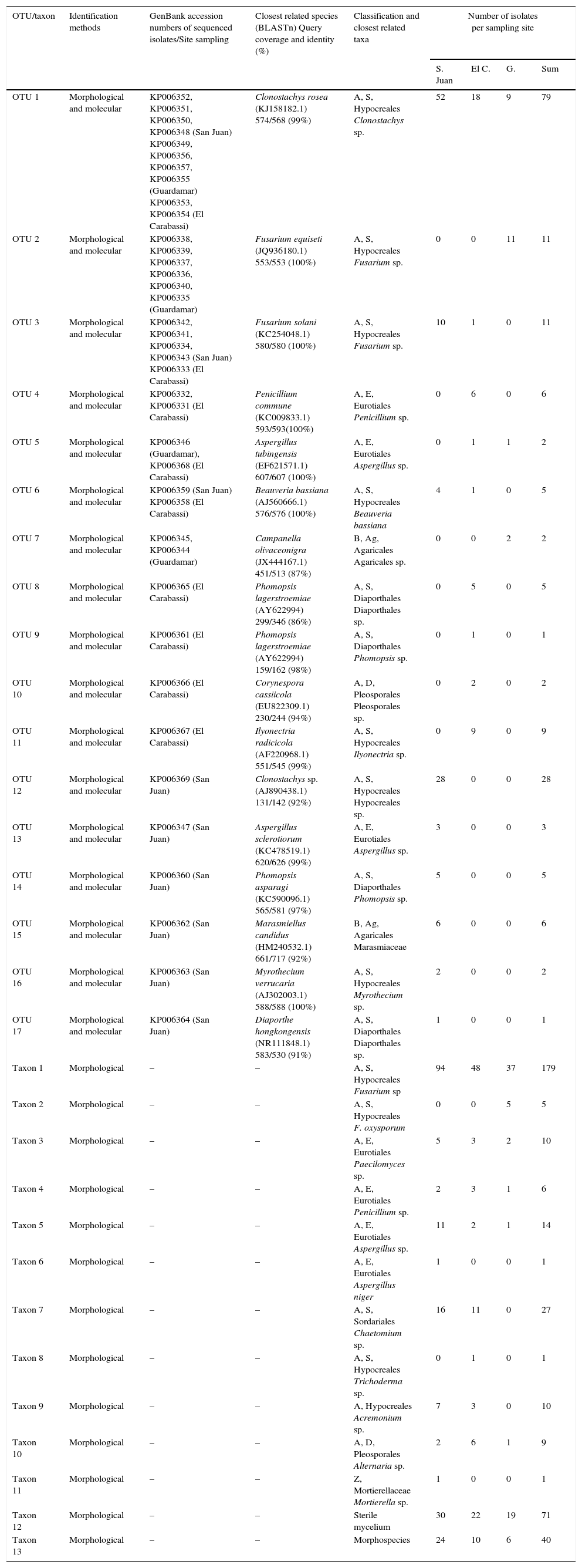

Incidence of endophytes was highest in San Juan, representing more than 55.5% of the total number of isolates (Table 1). This is due to the larger number of root pieces plated, and to the presence of endophytic bacteria in other samples which inhibited the fungal growth, especially in Guardamar. In our isolation-based study, the total fungal diversity detected was relatively high as compared to others studies.2,6,7 We detected a total of thirty OTUs and taxa belonging primarily to ascomycetous fungi (15 OTUs, 10 taxa), followed by Basidiomycota (2 OTUs) and Zygomycota (1 taxon). Our findings are consistent with the results of previous studies on other hosts, in which a predominance of ascomycetes has been reported as a characteristic of endophytic root and leaf communities.3,12,13,16,20,21 The Ascomycota includes fungi of economic importance ranging from virulent plant pathogens to effective agents of biological control, and from producers of antibiotics to sources of potent mycotoxins.18 Taxon 1 was the most frequently detected group, overall and across sites, and it could be ascribed to genus Fusarium by morphological means (Table 2). Fusarium species are adapted to a wide range of geographical sites, climatic conditions, ecological habitats, and host plants. The second most frequent group of isolates, OTU1, also belonged to the Hypocreales, and was related to Clonostachys rosea (Table 2). This species (syn. Gliocladium roseum22) is commonly found in several different terrestrial and freshwater environments23 and has been shown to successfully control a diversity of plant pathogens in greenhouses and in the field.25 Considering that this species was commonly found as an endophyte of healthy palm trees in all three locations sampled, it would appear to be a good candidate for further studies on its potential as a biological control agent of date palms diseases.

Data summary and classification of endophytic fungi colonizing roots of date palms in three dunes of SE Spain into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and morphological taxa.

| OTU/taxon | Identification methods | GenBank accession numbers of sequenced isolates/Site sampling | Closest related species (BLASTn) Query coverage and identity (%) | Classification and closest related taxa | Number of isolates per sampling site | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. Juan | El C. | G. | Sum | |||||

| OTU 1 | Morphological and molecular | KP006352, KP006351, KP006350, KP006348 (San Juan) KP006349, KP006356, KP006357, KP006355 (Guardamar) KP006353, KP006354 (El Carabassi) | Clonostachys rosea (KJ158182.1) 574/568 (99%) | A, S, Hypocreales Clonostachys sp. | 52 | 18 | 9 | 79 |

| OTU 2 | Morphological and molecular | KP006338, KP006339, KP006337, KP006336, KP006340, KP006335 (Guardamar) | Fusarium equiseti (JQ936180.1) 553/553 (100%) | A, S, Hypocreales Fusarium sp. | 0 | 0 | 11 | 11 |

| OTU 3 | Morphological and molecular | KP006342, KP006341, KP006334, KP006343 (San Juan) KP006333 (El Carabassi) | Fusarium solani (KC254048.1) 580/580 (100%) | A, S, Hypocreales Fusarium sp. | 10 | 1 | 0 | 11 |

| OTU 4 | Morphological and molecular | KP006332, KP006331 (El Carabassi) | Penicillium commune (KC009833.1) 593/593(100%) | A, E, Eurotiales Penicillium sp. | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| OTU 5 | Morphological and molecular | KP006346 (Guardamar), KP006368 (El Carabassi) | Aspergillus tubingensis (EF621571.1) 607/607 (100%) | A, E, Eurotiales Aspergillus sp. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| OTU 6 | Morphological and molecular | KP006359 (San Juan) KP006358 (El Carabassi) | Beauveria bassiana (AJ560666.1) 576/576 (100%) | A, S, Hypocreales Beauveria bassiana | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| OTU 7 | Morphological and molecular | KP006345, KP006344 (Guardamar) | Campanella olivaceonigra (JX444167.1) 451/513 (87%) | B, Ag, Agaricales Agaricales sp. | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| OTU 8 | Morphological and molecular | KP006365 (El Carabassi) | Phomopsis lagerstroemiae (AY622994) 299/346 (86%) | A, S, Diaporthales Diaporthales sp. | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| OTU 9 | Morphological and molecular | KP006361 (El Carabassi) | Phomopsis lagerstroemiae (AY622994) 159/162 (98%) | A, S, Diaporthales Phomopsis sp. | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| OTU 10 | Morphological and molecular | KP006366 (El Carabassi) | Corynespora cassiicola (EU822309.1) 230/244 (94%) | A, D, Pleosporales Pleosporales sp. | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| OTU 11 | Morphological and molecular | KP006367 (El Carabassi) | Ilyonectria radicicola (AF220968.1) 551/545 (99%) | A, S, Hypocreales Ilyonectria sp. | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| OTU 12 | Morphological and molecular | KP006369 (San Juan) | Clonostachys sp. (AJ890438.1) 131/142 (92%) | A, S, Hypocreales Hypocreales sp. | 28 | 0 | 0 | 28 |

| OTU 13 | Morphological and molecular | KP006347 (San Juan) | Aspergillus sclerotiorum (KC478519.1) 620/626 (99%) | A, E, Eurotiales Aspergillus sp. | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| OTU 14 | Morphological and molecular | KP006360 (San Juan) | Phomopsis asparagi (KC590096.1) 565/581 (97%) | A, S, Diaporthales Phomopsis sp. | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| OTU 15 | Morphological and molecular | KP006362 (San Juan) | Marasmiellus candidus (HM240532.1) 661/717 (92%) | B, Ag, Agaricales Marasmiaceae | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| OTU 16 | Morphological and molecular | KP006363 (San Juan) | Myrothecium verrucaria (AJ302003.1) 588/588 (100%) | A, S, Hypocreales Myrothecium sp. | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| OTU 17 | Morphological and molecular | KP006364 (San Juan) | Diaporthe hongkongensis (NR111848.1) 583/530 (91%) | A, S, Diaporthales Diaporthales sp. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Taxon 1 | Morphological | – | – | A, S, Hypocreales Fusarium sp | 94 | 48 | 37 | 179 |

| Taxon 2 | Morphological | – | – | A, S, Hypocreales F. oxysporum | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Taxon 3 | Morphological | – | – | A, E, Eurotiales Paecilomyces sp. | 5 | 3 | 2 | 10 |

| Taxon 4 | Morphological | – | – | A, E, Eurotiales Penicillium sp. | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| Taxon 5 | Morphological | – | – | A, E, Eurotiales Aspergillus sp. | 11 | 2 | 1 | 14 |

| Taxon 6 | Morphological | – | – | A, E, Eurotiales Aspergillus niger | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Taxon 7 | Morphological | – | – | A, S, Sordariales Chaetomium sp. | 16 | 11 | 0 | 27 |

| Taxon 8 | Morphological | – | – | A, S, Hypocreales Trichoderma sp. | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Taxon 9 | Morphological | – | – | A, Hypocreales Acremonium sp. | 7 | 3 | 0 | 10 |

| Taxon 10 | Morphological | – | – | A, D, Pleosporales Alternaria sp. | 2 | 6 | 1 | 9 |

| Taxon 11 | Morphological | – | – | Z, Mortierellaceae Mortierella sp. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Taxon 12 | Morphological | – | – | Sterile mycelium | 30 | 22 | 19 | 71 |

| Taxon 13 | Morphological | – | – | Morphospecies | 24 | 10 | 6 | 40 |

A, Ascomycota; B, Basidiomycota; Z, formerly called Zygomycota; S, Sordariomycetes; E, Eurotiomycetes; D, Dothideomycetes; Ag, Agaricomycetes; S. Juan, San Juan; El C., El Carrabassi; G, Guardamar.

The occurrence of the dominant endophytic fungi (taxon 1, OTU1, taxon 13, and taxon 12; Table 2) across sampling sites was compared with the χ2 test. Significant differences were found between sites, with highest frequencies in San Juan, and lowest in Guardamar, for taxon 1 (χ2=30.65, P<0.001), OTU1 (χ2=39.06, P<0.001), and taxon 13 (χ2=13.40, P=0.001). There were no evident differences in occurrence of taxon 12 (χ2=2.73, P=0.255).

Sterile mycelia were remarkably common in this study, representing 71 isolates of the total fungal groups. However, it is difficult to determine whether these isolates are naturally sterile or if they have simply lost the ability to sporulate in culture. OTU6, related to the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana, was found as an endophyte in date palms in dunes of San Juan and El Carabassi. Beauveria spp. have been used as biological control agents of soil and phylloplane insect pests.5 More recently, date palms worldwide are suffering from severe infestations by the red palm weevil (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus).14 Natural epizootics of B. bassiana on R. ferrugineus have been found in areas near the sites studied in this work.10 Therefore, the presence of this fungus as a natural endophyte of date palm roots is of great significance. The results of this work open the possibility of finding specific fungal isolates with the potential for biocontrol, or for the discovery of new antagonists such as mycoparasites or producers of useful secondary metabolites that could limit the damage caused by date palm diseases such as bayoud, or pests such as the red palm weevil.

The authors wish to thank the Algerian Ministry of Higher Education and Blida University the award of a scholarship to complete this research. We also thank the staff of the Laboratory of Plant Pathology, Department of Marine Sciences and Applied Biology, Multidisciplinary Institute for Environmental Studies (MIES) Ramón Margalef, University of Alicante, where the experimental work was carried out.