Coccidioidomycosis is one of the most important endemic mycoses in Northern Mexico. However, diagnosing this disease can be challenging, particularly in patients who do not reside in endemic areas.

Case reportThe case of a Mexican HIV+ patient who developed fever, general malaise, a severe cough, and dyspnea during a stay in Acapulco, Guerrero, Mexico, is presented. Since various diseases are endemic to the state of Guerrero, the doctors originally suspected that the patient had contracted influenza A (H1N1), Q fever, or tuberculosis. All the diagnostic tests for those diseases were negative. The patient had received numerous mosquito bites while staying in Acapulco, and a nodule had appeared on his right cheek. Therefore, malaria, cryptococcosis, and histoplasmosis were also suspected, but those infections were also ruled out through diagnostic tests. A direct microscopic examination was performed using KOH on a sample taken from the cheek nodule. The observation of spherules suggested the presence of a species of Coccidioides. The fungus was isolated, and its identity was confirmed by phenotypic and molecular methods. The geographic area in which the infection was likely acquired was identified by random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis. The results suggested a probable endogenous reactivation.

ConclusionsThis clinical case illustrates the difficulties associated with diagnosing coccidioidomycosis in non-endemic areas.

La coccidioidomicosis es una de las micosis endémicas más importantes del norte de México y su diagnóstico puede ser difícil, particularmente en pacientes que no residen en zonas endémicas.

Caso clínicoSe presenta el caso de un hombre mexicano positivo para el VIH, que comienza con fiebre y afectación del estado general, tos intensa y disnea, durante una estancia en Acapulco, Guerrero (México). Dado que el estado de Guerrero es considerado endémico para diferentes enfermedades, los médicos sospecharon de influenza A (H1N1), fiebre Q o tuberculosis. Estas enfermedades fueron descartadas mediante pruebas diagnósticas. Durante su estancia en Acapulco el paciente presentó múltiples picaduras por mosquitos; la aparición de un nódulo en la mejilla derecha hizo sospechar de paludismo, criptococosis o histoplasmosis, enfermedades que fueron también descartadas. Ante este resultado se realizó un examen directo con KOH por microscopia óptica del nódulo; las esférulas observadas apuntaban a la presencia de un hongo del género Coccidioides. El hongo fue aislado en cultivo y se confirmó su identidad por métodos fenotípicos y moleculares. A través de amplificación aleatoria de ADN polimórfico se infirió el área geográfica donde probablemente se adquirió la infección, lo que evidenció una reactivación endógena.

ConclusionesLa presentación de este caso clínico muestra las dificultades para diagnosticar la coccidioidomicosis cuando se presentan casos en áreas no endémicas.

Coccidioidomycosis is one of the most important endemic mycoses in Northern Mexico (MX). The clinical manifestations of coccidioidomycosis can be confused with those of other disease entities; thus, diagnosing this disease can be challenging, particularly for patients who do not reside in endemic areas.3,9,10

A 47-year-old Mexican man who had always lived in Mexico City was diagnosed with HIV in 1990. He was a slow progressor and began receiving antiretroviral therapy in 1999. At the time of the illness described in this report (year 2009), the patient was undergoing a treatment with efavirenz, emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; he had a viral load of less than 50copies/ml and a CD4 cell count of 670ml−1. In the previous five years, the patient had made several trips to cities in northern Mexico, including Monterrey and Tijuana. In March 2009, he experienced three mild episodes of influenza and was treated with azithromycin. In May 2009, while on a trip to Acapulco, Guerrero, he developed a fever and general malaise; three days later, he developed a severe cough and dyspnea. Given the influenza A (H1N1) epidemic of 2009 in MX and the United States, this disease was suspected, and the patient was immediately hospitalized. A chest X-ray produced nonspecific findings and revealed diffuse infiltrates that were predominantly located at the base of the right lung and perihilar nodules (Fig. 1). The patient was treated with intravenous oseltamivir and clarithromycin. A RT-PCR test13 was performed to diagnose influenza A (H1N1); however, this test yielded negative results.

Because Plasmodium is endemic to Guerrero, malaria was suspected. A thick blood smear was prepared for Giemsa malaria microscopy, which yielded a negative result. Q fever is also endemic to Guerrero. An ELISA [Panbio®Coxiella burnetii, Buenos Aires] was performed to identify the etiologic agent. The patient was administered doxycycline before the test results were available; these results were also negative. Subsequently, blood and sputum were obtained. Smears and cultures were prepared to test for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which was not found either.

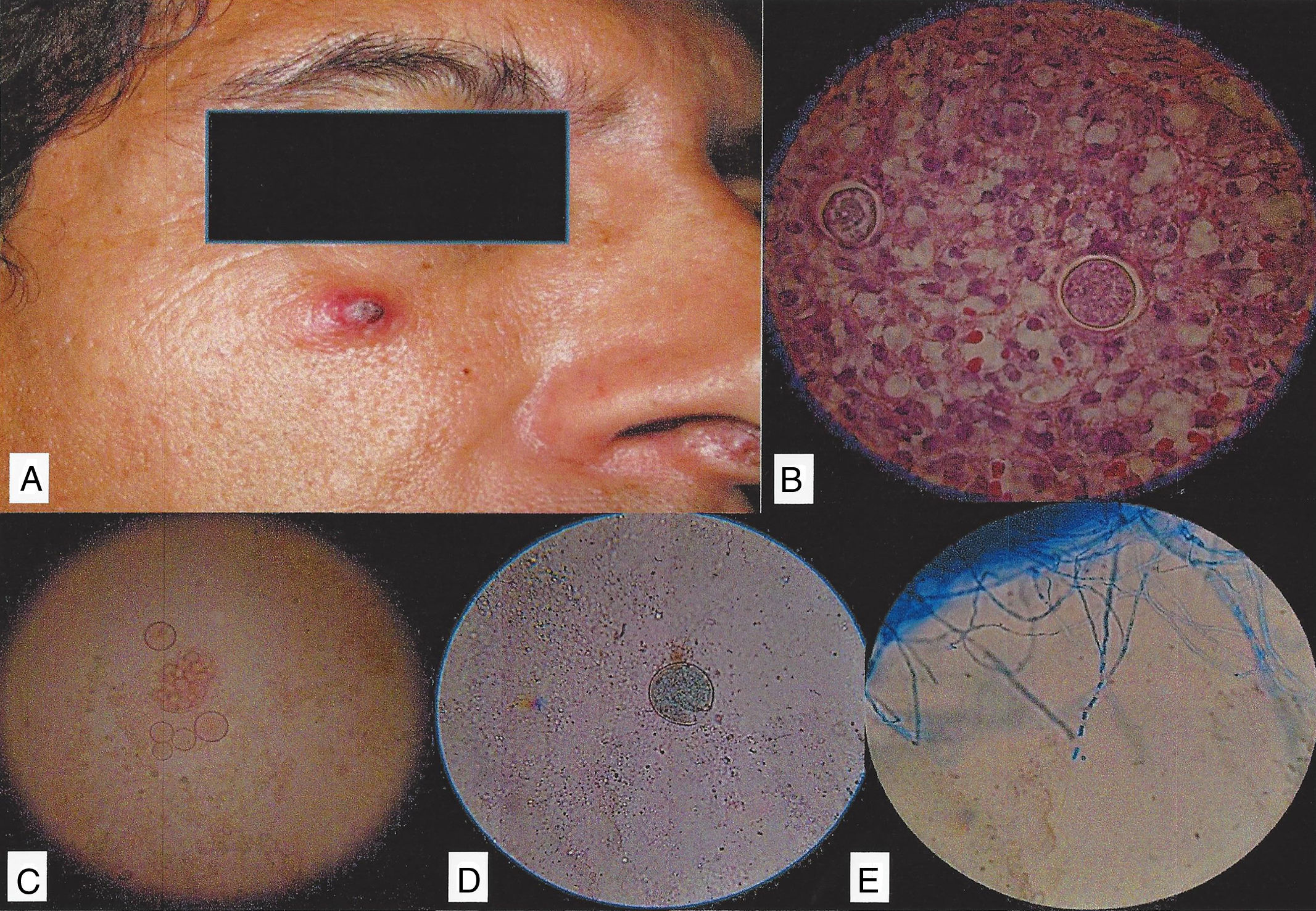

The patient continued to present cough, dyspnea, fever of up to 40°C and mild general malaise for a month. His symptoms gradually subsided, although a low-grade fever and mild general malaise persisted for two months. The patient reported that he had experienced pruritus caused by insect bites while staying in Guerrero at the beginning of his illness. In particular, he had received multiple insect bites and had not paid attention to a 1-cm nodule that had appeared on his right cheek (Fig. 2A). This pruritic, erythematous nodule exhibited serohematic crust formation on its surface. Intense pruritus persisted following the patient's trip and continued after overall clinical improvement had occurred. Triamcinolone infiltration was performed to treat the persistent right cheek nodule and the patient's pruritus. Samples from this nodule were obtained and were tested using 15% KOH and cytology smears stained with methenamine silver and periodic acid-Schiff reagent (Fig. 2B). No structures compatible with Histoplasma capsulatum or Cryptococcus neoformans were observed; however, spherules compatible with Coccidioides were present (Fig. 2B–D). A sample from the patient's nodule was cultured in Mycobiotic agar (Bioxon®, Cd. Mx., MX). The resulting isolate (numbered 34701) exhibited macromorphological characteristics typical of the Coccidioides genus. The colony had a hairy texture with smooth edges, a white front and a light brown back. Examinations of the microscopic morphology revealed septate hyaline hyphae and thick-walled arthroconidia, which are structures typically associated with Coccidioides species (Fig. 2E).

(A) The patient with an erythematous nodule. (B) A biopsy of a skin sample, with Coccidioides spp. spherules stained with periodic acid-Schiff. (C and D) Spherules present in the nodule. (E) Direct examination of the culture, revealing the presence of Coccidioides mycelium with arthroconidia.

To confirm the identity of the fungus, PCR was performed, and phylogenetic inference was conducted.1,4,5 The sequence obtained from isolate 34701 (accession number KF683308) exhibited >99% nucleotide identity with partial Ag2/PRA gene sequences obtained from Coccidioides posadasii isolates; thus, isolate 34701 was identified as C. posadasii. Treatment with amphotericin B (0.7–1mg/kg/day) was prescribed and produced a noticeable improvement. Therapy with itraconazole (200mg twice per day) was continued for six months, until the symptoms and signs of the infection had resolved.

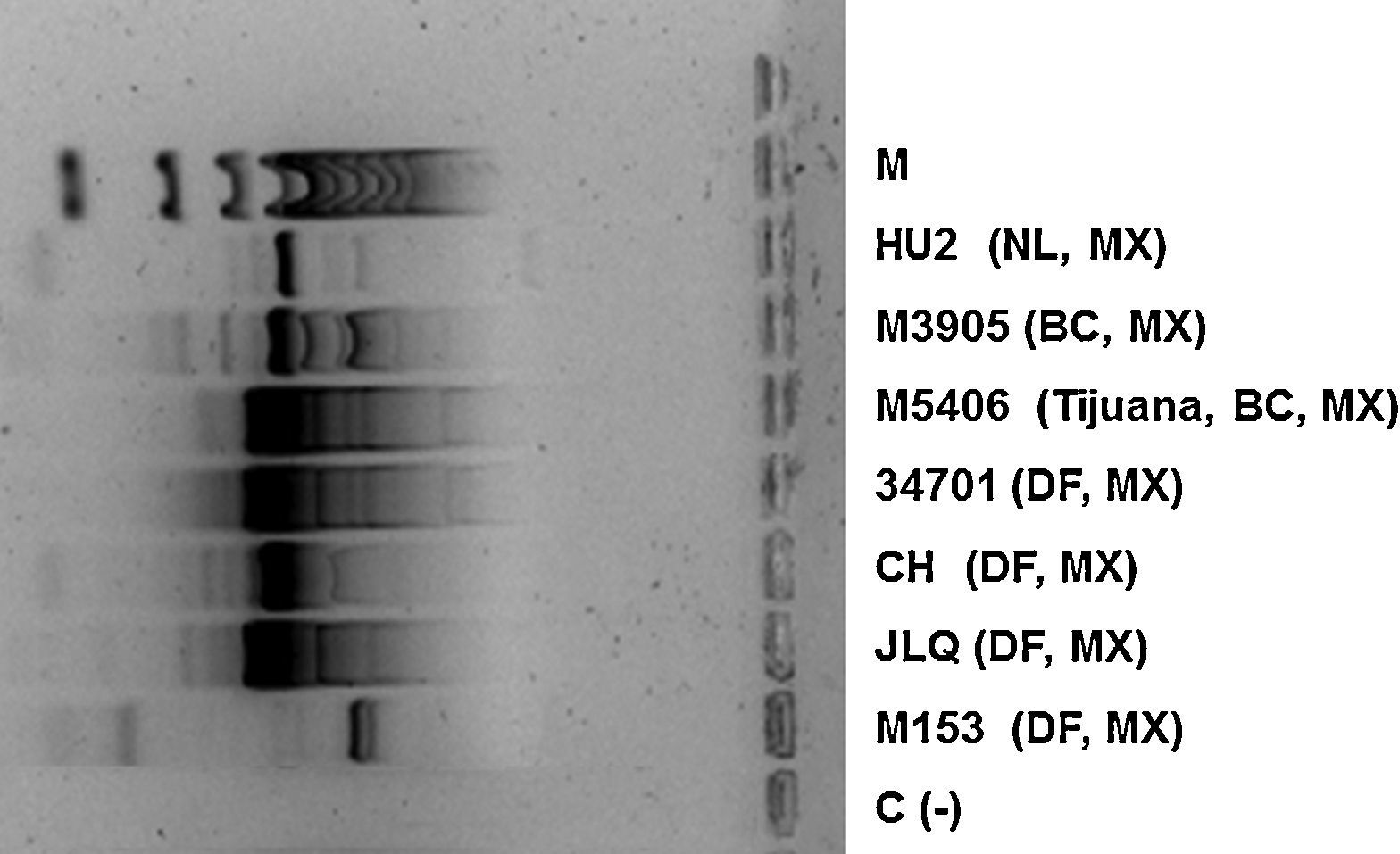

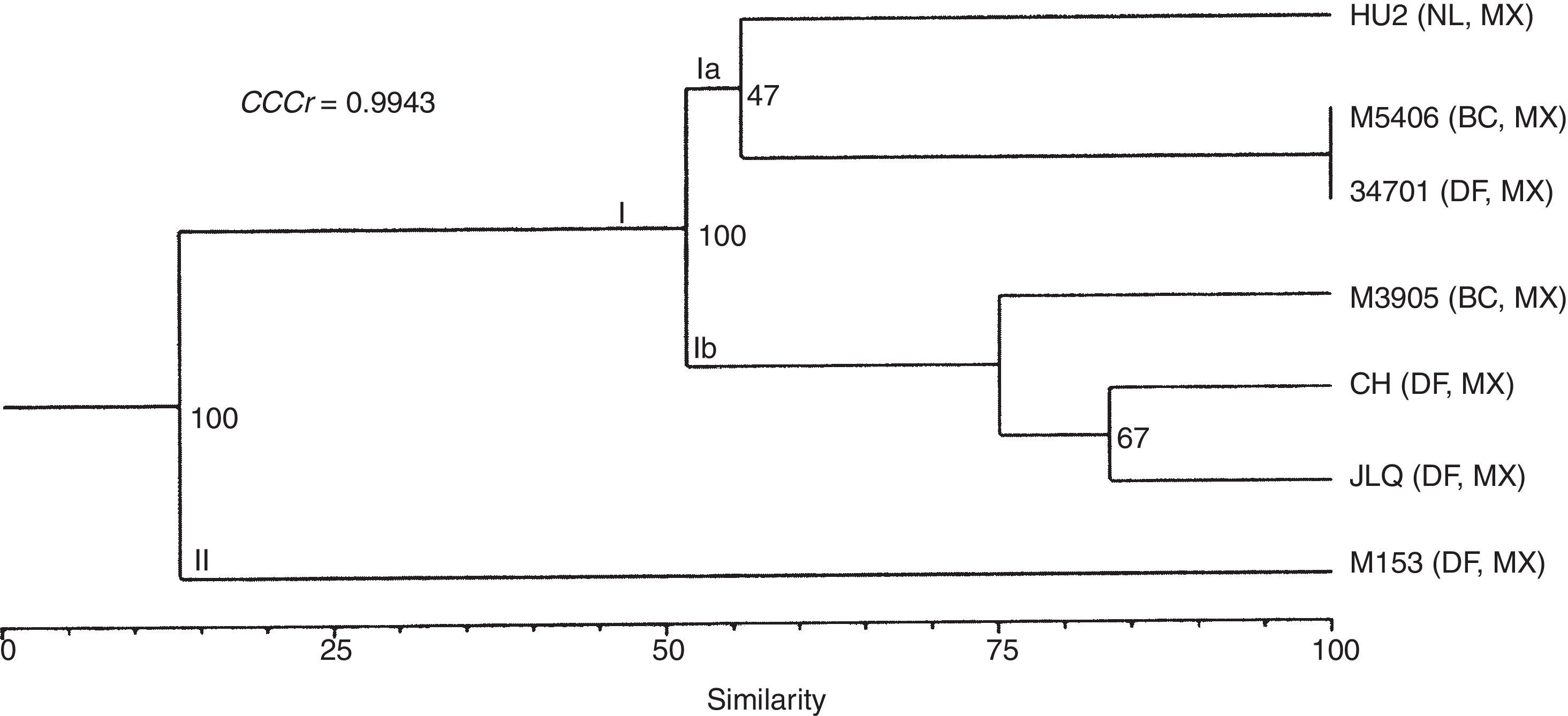

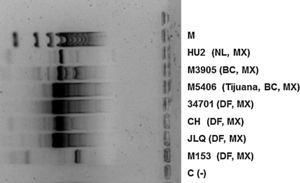

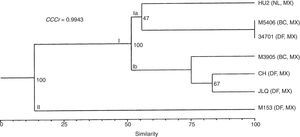

To infer the likely geographic area where the infection was acquired, we used the random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) method with the oligonucleotides 1281, 1283, 12538,15 and R1202,14 to compare isolate 34701 with six clinical isolates of C. posadasii that were used as references (Fig. 3). The genetic relationships between isolates were assessed using a dendrogram constructed by applying the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA). The reliability of this dendrogram was evaluated by using the cophenetic correlation coefficient (CCCr) determined via Mantel's test.11 The indices of support for internal branches were generated by conducting 5000 replications of the bootstrap procedure.6 The dendrogram identified two groups. Group I consisted of the M5406, 34701, and HU2 C. posadasii isolates. Subgroup Ib consisted of three isolates (CH, JLQ, and M3905). Group II consisted of one C. immitis isolate (M153) (Fig. 4). The calculated CCCr of 0.9943 (p≤0.002) suggests that the dendrogram accurately represented the original genetic similarities between isolates.

The described case demonstrates the challenges associated with reaching a diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis in a non-endemic area. As the patient lives in Mexico City and several years since his last trip to northern MX had passed, we did not suspect coccidioidomycosis until spherules suggestive of a Coccidioides species were discovered in the examined nodule. Another issue related to diagnosing this disease is that the symptoms are not specific to coccidioidomycosis and can mimic those of several other diseases. In addition, in the described case, several samples were sent to the United States to have tests conducted on them, a time-consuming process that delayed the diagnosis. Furthermore, in the microscopic analysis using KOH and the histopathological preparations, diverse forms of Coccidioides are often observed, ranging from arthroconidia and septate hyphae with multiple morphologies to transitioning conidia, spores, mature spherules and endospore-releasing spherules, which difficult the identification of this microorganism.12 Another important consideration is that coccidioidomycosis is not a reportable disease in MX. Therefore, the true incidence of this disease is unknown, and it is not regarded as an emerging disease.3 So it is recommended to include the patient's places of residence (permanent and temporary) in the last five years in his or her medical history to obtain an accurate diagnosis.

A phylogenetic analysis confirmed that isolate 34701 belonged to the C. posadasii species, prevalent in MX.7 Similarly, the RAPD method was useful for determining the likely geographic area where the patient's infection was acquired. This analysis revealed an identity of 100%, with 100% bootstrap support between the DNA sequences of an isolate from Tijuana, MX, and the patient's isolate (34701). This result suggested that the patient was infected during one of his trips to Baja California, a state that is regarded as endemic for coccidioidomycosis,3 and that the disease could have resulted from an endogenous reactivation.

Although the patient's isolate exhibited 100% similarity to an isolate from Tijuana, we could not definitively determine the source of infection because such determinations require the acquisition of DNA from environmental samples and the comparison of the polymorphic profiles of this DNA with those of DNA from the clinical isolate. Therefore, we can only suggest the probable geographic area where the patient acquired his infection.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.

This project was funded by PAPIIT-DGAPA (IN215509-3).