Some patients with a hip fracture also present a concomitant upper limb fracture. We want to know whether these patients have a worse functional level and whether they have any differences in various clinical parameters compared with patients with an isolated hip fracture.

Material and methodsWe retrospectively reviewed 1061 discharge reports from the Orthogeriatrics Unit. We collected information on several clinical parameters of the fractures. Subsequently, we performed a statistical analysis of the data by comparing the associated fracture group with the isolated fracture group.

ResultsWe detected 44 patients with associated upper limb fracture, 90.9% were women (40) and the average age was 84.45 years. Eighty-one point eight percent of the upper limb fractures were distal radius or proximal humerus. Pertrochanteric fractures were the most common (none of them were subtrochanteric fractures). Surgical delay was 2.60 days and the average hospital stay was 12.30 days. Sixty-four point three percent were nail surgery and 31% arthroplasty. The mean Barthel Index score was 84.88 (P=.021). Fifty-two point 5% of the patients in the study group were referred to a functional support unit (P=.03). The in-hospital mortality rate was 4.2%, with no differences between groups.

ConclusionsPatients with an associated fracture have a higher previous functional capacity and they are more independent. Nevertheless, after the fracture they need more help from the healthcare system for optimal functional recovery.

Hay una proporción de pacientes con fractura de cadera que tienen una fractura de miembro superior concomitante. Queremos conocer si estos pacientes muestran un peor nivel funcional y si presentan diferencias en distintos parámetros clínicos con respecto a los que tienen una fractura aislada de cadera.

Material y métodosSe han revisado retrospectivamente 1.061 informes de alta de la Unidad de Ortogeriatría del H. U. La Paz de Madrid. Se recopiló información sobre distintos parámetros clínicos de las fracturas presentadas. Posteriormente se comparó el grupo de fractura asociada con el de fractura aislada mediante un análisis estadístico.

ResultadosSe detectaron 44 pacientes con una fractura de miembro superior asociada, el 90,9% fueron mujeres (40) y la media de edad fue de 84,45años. El 81,8% de las fracturas de miembro superior fueron de radio distal o de húmero proximal. La demora quirúrgica fue de 2,60días y la estancia media hospitalaria, de 12,30días. El 64,3% fueron intervenciones con clavo-tornillo y el 31%, artroplastias. La media del índice de Barthel fue de 84,88 (p=0,021). El 52,5% de los pacientes del grupo a estudio fueron derivados a un centro de apoyo funcional (p=0,03). La mortalidad global intrahospitalaria fue del 4,2%, sin diferencias entre los grupos.

ConclusionesLos pacientes que presentan una fractura asociada tienen mayor capacidad funcional previa y son más independientes. Tras la fractura necesitan una mayor ayuda por parte del sistema sanitario para su óptima recuperación funcional.

Trauma due to a fall is one of the most frequent reasons why patients visit emergency departments. One of the results of such trauma is that patients suffer a hip fracture. Fractures of this type, which are strongly associated with osteoporosis, have a high degree of morbimortality and lead to major costs for the Spanish National Health System over a year.1

It is estimated that in Spain there is an average incidence of from 500 to 600 cases of hip fracture per 100,000 elderly people/year. This incidence is also estimated to differ between the sexes, as in the case of women it amounts to 700 cases per 100,000elderlywomen/year.2,3

Fracture of the proximal femur is therefore one of the main health problems affecting elderly patients.4 Considering the demographic evolution towards an increasing elderly population due to the increase in life expectancy, the incidence of proximal femur fractures has increased considerably in European communities,5 and this trend will continue in the coming years.6,7 The mortality rate associated with fractures of this type is high during hospitalisation (5%), as well as at 3 months (15%) or at one year after the fracture (20–30%).8

After trauma some patients do not only have isolated fracture of the proximal femur, as they may also have a concomitant fracture of an upper limb.

There is discussion in the traumatological community about the physical condition of these patients. Some authors such as Di Monaco et al.9 state that patients who suffer a hip fracture associated with the fracture of an upper limb are in worse physical condition than those patients who only have hip fracture, given that as they have two or more concomitant fractures their level of bone mineralisation as well as their basal state and mobility are worse.

On the contrary, other authors such as Lin et al.10 and Shabat et al.11 state that the existence of an upper limb fracture associated with a hip fracture is a sign that the patient is in a better or at least equal functional state, given that they are still able to defend themselves against trauma using a reflex mechanism that attempts to slow a fall using an upper limb.

Another reason for undertaking this study was that patients with this type of associated fracture are more restricted in support and walking due to the difficulty or impossibility of using aids such as crutches, walking sticks or Zimmer frames.

Are the patients who fracture an upper limb at the same time as they suffer a hip fracture more fragile? Are these patients in worse physical and medical condition?

Objectives- •

To evaluate whether patients with a concomitant hip and upper limb fracture have better or worse functional capacity.

- •

To discover whether there are statistically significant differences in a range of medical, surgical and treatment parameters between the groups studied.

- •

To evaluate whether the clinical management of patients with an associated fracture differs from that of the group with a single fracture.

1061 discharge reports were reviewed retrospectively. They correspond to patients treated from January 2010 to December 2014.

Based on the data obtained two groups were formed. One group consisted of patients with a single hip fracture, while the other was composed of patients with an upper limb fracture associated with a hip fracture. Both groups were then compared.

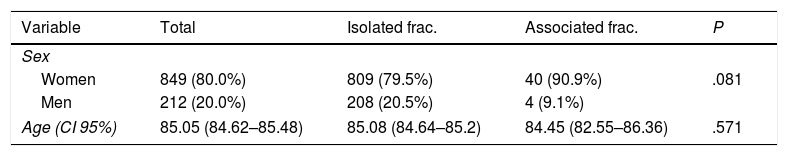

All of the patients included in the database had hip fracture. This could either be isolated (1.017; 95.9%) or associated with an upper limb fracture (44; 4.1%). 849 of the patients included in the study were women (80%) and 212 were men (20%), with an average total age of 85.05 years old (CI 95%: 84.62–85.48). The average age of the patients who only had a hip fracture was 85.08 years old (CI 95%: 84.64–85.52) while the average age of those with an associated fracture was 84.45 years old (CI 95%: 82.55–86.36) (Table 1).

Hip fractures were classified as subcapital femur fracture (440; 41.7%), pertrochanter (559; 52.9%) or subtrochanter (57; 5.4%). For inclusion in the group of associated fractures, patients had to have a hip fracture plus at least one of the following fractures: the proximal humerus (14; 31.8%), humeral diaphysis (3; 6.8%), elbow (5; 11.4%) or distal radius (22; 50%). Humeral luxations were included in the study (3) in the proximal humerus fractures group, due to the need for immobilisation during 3–4 weeks.

The surgical technique used for the hip fracture was documented from the discharge reports (nail-screw, arthroplasty, screw-plate or cannulated screws), together with the delay prior to hip surgery (days), the duration of hospitalisation (days), destination at discharge (home or rehabilitation unit), vitamin D levels, treatment (yes/no) with calcium, vitamin D, calcium and vitamin D together, bisphosphanates, corticoids, IBP, neuroleptics or antidepressive drugs, benzodiazepines, anti-dementia and antiparkinson drugs, and a check was made to discover whether the patient died during admission.

The functional capacity of patients was analysed using the Barthel Index, the Functional Ambulatory Classificator (FAC) and the Red Cross Functional Scale (RCF). The Barthel Index is one of the most widely used scales in the world to evaluate dependency. Its scores run from 10 (15 in the case of moving between bed-armchair) if a range of activities are performed, such as eating, getting dressed or urinating independently, down to 0 if the patient is completely dependent to undertake them. The sum of scores in all of the categories shows the degree to which a patient is dependent. They are totally dependent if their score is <20, severely dependent at from 20 to 40, moderately dependent from 45 to 55 and slightly dependent if they score 60 points or more.12 The FAC evaluates patient walking, classifying it in six variables depending on the degree to which the patient requires aid. 0 corresponds to patients who either do not walk or require the aid of two people to do so, and 5 corresponds to patients who are able to walk unaided over uneven ground.13

The RCF scale classifies patient disability into six categories. 0 is assigned to patients who are totally dependent, and 5 is assigned to those who are immobilised in bed or an armchair, who are completely incontinent or who require continuous nursing care.14

The Pfeiffer test was used to evaluate the cognitive state of patients. This questionnaire contains 10 items, and the cut-off point to consider cognitive deterioration is set at 3 errors or more if the patient knows how to read and write, and at 4 or more if this is not the case.15 In this study the educational level of the patients was not taken into account.

Data were recorded using the 2013 version of the Excel computer program. Statistical analysis of data was carried out by the Biostatistics Service using the IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 program (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA). Comparative analysis of the data in the group of patients with hip fracture and another associated upper limb fracture took place with the data in the group of patients with isolated hip fracture.

Differences in terms of sex, surgical technique, destination at discharge, different treatments and death were compared using Pearson's chi-squared test. Statistical significance was taken into consideration in all of the comparisons made using the chi-squared test with bilateral comparison of the distribution.

Differences in age at admission, surgical delay, the duration of hospitalisation, the Barthel Index, the FAC, the RCF scale, the Pfeiffer test and levels of vitamin D and patient PTH in both groups were compared using the ANOVA test and Snedecor's F distribution.

The level of statistical significance was set at P<.05.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee.

ResultsThe average age of the group of patients with isolated hip fracture was 85.08 years old (84.64–85.52), while in the group with an upper limb fracture it was 84.45 years old (82.55–86.36) (P=.571).

Considering the proportion of men and women in both groups, the associated fracture group was found to contain 40 women (90.9%) and 4 men (9.1%), while the isolated fracture group contained 809 women (79.5%) and 208 men (20.5%) (P=.08).

Of the 1061 patients in the study, 440 suffered a subcapital fracture (41.5%), 559 pertrochanter fracture (52.7%) and 57 patients suffered a subtrochanter fracture (5.4%). Analysis found 5 patients who could not be classified in any of these groups (0,4%) because their discharge report did not show the type of hip fracture they had suffered.

44 patients were identified who had a concomitant upper limb fracture together with a hip fracture. 14 of these 44 patients had a proximal humerus fracture (31.8%) (and this group included one patient with 3 fractures: proximal femur, proximal humerus and distal radius). Together with this, 3 diaphyseal humerus fractures were detected (6.8%), as well as 5 elbow fractures (11.4%) and 22 distal radius fractures (50%).

The association of an upper limb fracture with a subcapital fracture occurred 15 times (34.1%), and this association arose in 29 cases (65.9%) of pertrochanter fracture. It did not occur in any case of subtrochanter fracture. In 18 cases the upper limb fracture was subsidiary to surgical treatment, although no data on the type of surgery used were available.

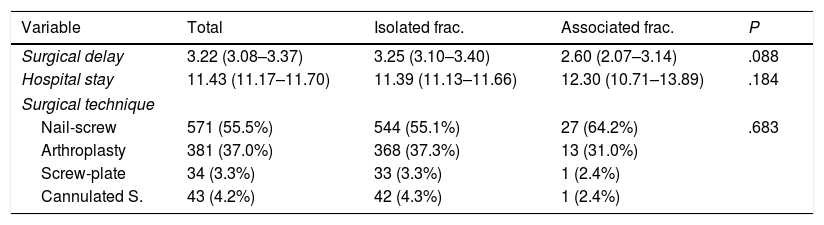

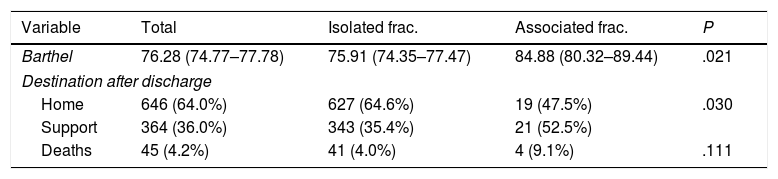

The average delay before surgery was 2.60days in the associated fracture group (2.07–3.14) and 3.25days in the isolated hip fracture group (3.10–3.40) (P=.08), while the total hospitalisation time was 12.30 days (10.71–13.89) and 11.39 days (11.13–11.66), respectively (Table 2). The associated fracture group scored an average of 84.88 (80.32–89.44) on the Barthel Index, while the isolated hip fracture group scored an average of 75.91 (74.35–77.47). The patients with associated upper limb and hip fracture therefore had a higher previous Barthel Index score (slight disability) than the patients with an isolated hip fracture (moderate disability). This difference is statistically significant (P=.02) (Table 3). The FAC score was 3.93 (3.60–4.26) in the associated fracture group and 3.65 (3.57–3.73) in the isolated hip fracture group (P=.176). The average RCF scale score in the associated upper limb fracture group was 1.14 (.75–1.53) and in the isolated hip fracture group it stood at 1.29 (1.21–1.37) (P=.468); The average Pfeiffer index score in the study group was 3.36 (2.34–4.38), while in the isolated hip fracture group it was 3.85 (3.62–4.04) (P=.351). The average vitamin D level found in the associated fracture group of patients was 14.14 (10.86–17.43), and 15.29 in the isolated hip fracture group (14.27–16.23) (P=.650).

Comparative data on hospital and surgical treatment of the groups.

| Variable | Total | Isolated frac. | Associated frac. | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical delay | 3.22 (3.08–3.37) | 3.25 (3.10–3.40) | 2.60 (2.07–3.14) | .088 |

| Hospital stay | 11.43 (11.17–11.70) | 11.39 (11.13–11.66) | 12.30 (10.71–13.89) | .184 |

| Surgical technique | ||||

| Nail-screw | 571 (55.5%) | 544 (55.1%) | 27 (64.2%) | .683 |

| Arthroplasty | 381 (37.0%) | 368 (37.3%) | 13 (31.0%) | |

| Screw-plate | 34 (3.3%) | 33 (3.3%) | 1 (2.4%) | |

| Cannulated S. | 43 (4.2%) | 42 (4.3%) | 1 (2.4%) | |

Distribution of the Barthel Index, destination at discharge and deaths in the study.

| Variable | Total | Isolated frac. | Associated frac. | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barthel | 76.28 (74.77–77.78) | 75.91 (74.35–77.47) | 84.88 (80.32–89.44) | .021 |

| Destination after discharge | ||||

| Home | 646 (64.0%) | 627 (64.6%) | 19 (47.5%) | .030 |

| Support | 364 (36.0%) | 343 (35.4%) | 21 (52.5%) | |

| Deaths | 45 (4.2%) | 41 (4.0%) | 4 (9.1%) | .111 |

1029 surgical operations were performed for hip fracture. In the upper limb fracture group 27 operations took place using a nail-screw (64.2%), while there were 13 arthroplasties (31%), one screw-plate (2.4%) and one operation using cannulated screws (2,4%). In the isolated hip fracture group 571 operations used a nail-screw (55.1%), and there were 368 arthroplasties (37.3%), 33 operations using a screw-plate (3.3%) and 42 operations using cannulated screws (4.3%) (Table 2).

Regarding the previous treatments of patients in the different groups, the only statistically significant difference was found for Parkinson's disease treatment. 6 patients in the associated upper limb fracture group were receiving antiparkinson treatment (13.6%; 48 were doing so in the isolated hip fracture group [4.7%]). 38 patients were not receiving antiparkinson treatment (86.4%; 969 in the isolated hip fracture group [95.3%]), so that with a statistically significant difference (P=.02) more patients in the associated fracture group were receiving antiparkinson treatment than was the case in the other group.

In the light of the findings the Barthel Index of the patients with antiparkinson treatment and an isolated hip fracture was compared with the Index of patients who were also treated for Parkinson's disease and also had an associated upper limb fracture. The average score in the associated fracture group was 82.50, while in the isolated hip fracture group it was 66.04. This difference was not statistically significant (P=.10).

Regarding destination at discharge (Table 3), 21 patients in the associated fracture group were sent to a functional support centre (52.5%; 343 in the isolated fracture group [35.4%]), while 19 patients were sent home (47.5%; 627 in the isolated fracture group [64.6%]). This shows that more patients in the upper limb fracture group were sent to a support centre, and this is statistically significant (P=.03).

No differences were found between the groups in terms of mortality. 4 patients (9.1%) in the associated fracture group died, while in the isolated hip fracture group 41 patients (4%) died. The overall mortality rate for all of the patients included was 4.2% (45 patients).

DiscussionProximal femur fractures are one of the pathologies with the highest number of associated complications, leading to loss of functionality and mortality in elderly patients.

Although in our environment some patients suffer a fractured upper limb and a proximal femur fracture in the same accident, there is a lack of full knowledge about their functional capacity as well as their physical condition.

The prevalence of patients with an upper limb fracture associated with a hip fracture in our population amounted to 4.1%, the same rate as the study by Di Monaco et al. found.9 This is slightly lower than the 5% described in other studies such as the one by Buecking et al.16 or the 4.6% described by Ong et al.17 The majority of the associated upper limb fractures are of the proximal humerus and distal radius (81.3%), these as is widely known being strongly associated with osteoporosis.

As is the case in previously published studies, there is a higher incidence of isolated as well as associated fractures in women than in men. Our study supports the finding of Ong et al.17 that there is a higher percentage of women in the associated fracture group than there is in the isolated hip fracture group. Nevertheless, our results here were not statistically significant (P=.08).

The average age in our population does not agree with the finding published by Mulhall et al.,18 as they found that patients with an associated fracture were older in a statistically significant way.

The sample in our study showed no significant difference in terms of vitamin D levels between the isolated and associated fracture groups. However, there is a generalised deficiency (<20ng/ml) in vitamin D levels in all of the patients admitted to the Orthogeriatric Unit.

This study found no differences between the groups in terms of the duration of hospitalisation. This agrees with the findings of Di Monaco et al.,19 and it is contrary to the finding described by Mulhall et al.,18 who found that patients with an associated upper limb fracture remained in hospital for longer than those with an isolated hip fracture.

This study found a statistically significant higher previous Barthel Index in the patients who had a concomitant fracture (P=.021). It is possible that patients who are less dependent and have conserved greater functional capacity are more likely to suffer an upper limb fracture associated with hip fracture. A possible explanation for this is the reflex mechanism, as was described above. These data contradict those published by Di Monaco et al.,9 as they observed that the Barthel Index at admission was higher in patients with an isolated hip fracture.

No significant differences were found in surgical delay (which was even found to be shorter in the associated fracture group) or in the type of hip operation performed. Osteosynthesis using a nail-screw was the most frequent technique in both groups, followed by arthroplasty.

More patients in the associated fracture group were sent to a functional support centre than was the case in the other group. This difference was statistically significant (P=.03) and may suggest that patients with an associated fracture have worse functional recovery, so that they require more aid by the Health System.

Regarding the treatment followed by patients, previous studies such as the one by Ong et al.17 describe a higher rate of prolonged corticoid use and multiple drug prescription (considered to consist of taking more than 4) in cases with concomitant upper limb fracture. Our study did not compare whether patients were taking multiple drugs or not, and it did not show that patients following treatment with steroids had more concomitant fractures. Nevertheless, this study did find that the number of patients under antiparkinson treatment was higher in the associated fracture group than it was in the group with an isolated fracture. This finding is contrary to the one described in the study by Ong et al.,17 which found higher prevalence of Parkinson's disease in the isolated fracture group.

Although the proportion of deaths was twice as high in the associated fracture group than it was in the isolated hip fracture group, this difference was not significant. In spite of this, overall patient mortality in our study (4.2%) was lower than the figure detected by Dr. Ojeda (7.73%).7

Our study has certain limitations. The information recorded was restricted to the Barthel Index at admission, so that the functional level of patients at discharge is unknown. The patients who were referred to functional support centres may lead to a shortening of the hospitalisation they required.

ConclusionsThe patients who had an upper limb fracture associated with a hip fracture had a better previous functional level than those with an isolated hip fracture. This finding may be explained by the greater capacity of these patients to defend themselves against harm by using their arms.

In spite of the above consideration, the said patients were more restricted in their functional recovery than those with an isolated hip fracture, and they were referred more often to support and functional rehabilitation centres. Their lack of ability to use walking aids such as walking sticks or Zimmer frames may play a significant role in this respect.

The presence of a concomitant upper limb fracture associated with a hip fracture has a greater impact on functional capacity than an isolated hip fracture.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments on human beings or animals took place for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they followed the protocols of their centre of work governing the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this paper.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank: our tutor and Professor Dr. Enrique Gil Garay, Head of the Traumatology Department in La Paz University Hospital, Madrid, for his dedication, availability and support during this work.

Paloma Herranz, secretary of the of the Traumatology Department in La Paz University Hospital, Madrid, for her help in data gathering.

The Biostatistics Department of La Paz Hospital, and more specifically Mr. Jesús Díez Sebastián, for his advice and help in the statistical analysis of this work.

Dr. José Luis Mauleón Álvarez de Linera and Dr. Teresa Alarcón Alarcón, Heads of the Orthogeriatrics Area, for allowing this work to proceed.

Please cite this article as: Gómez-Álvarez J, González-Escobar S, Gil-Garay E. Evaluación clínica de pacientes con fractura de cadera aislada y asociada a fractura de miembro superior. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2018;62:222–227.