Osteopetrosis is characterized by a considerable increase in bone density resulting in defective remodeling, caused by failure in the normal function of osteoclasts, and varies in severity. It is usually subdivided into three types: benign autosomal dominant osteopetrosis; intermediate autosomal recessive osteopetrosis; and malignant autosomal recessive infantile osteopetrosis, considered the most serious type. The authors describe a case of chronic osteomyelitis in the maxilla of a 6-year-old patient with Malignant Infantile Osteopetrosis. The treatment plan included pre-maxilla sequestrectomy and extraction of erupted upper teeth. No surgical procedure was shown to be the best to prevent the progression of oral infection. Taking into account the patient's general condition, if the patient develops severe symptomatic and refractory osteomyelitis surgery should be considered. The patient and his family are aware of the risks and benefits of surgery and its possible complications.

La osteopetrosis se caracteriza por un aumento considerable de la densidad ósea que resulta en un remodelado defectuoso, causado por mal funcionamiento de los osteoclastos, de severidad variable. Usualmente se divide en 3 tipos: osteopetrosis dominante autosómica benigna, osteopetrosis recesiva autosómica intermedia y osteopetrosis infantil recesiva autosómica maligna, considerado el tipo de mayor gravedad. Los autores describen un caso de osteomielitis crónica en el maxilar superior de paciente de 6 años de edad con osteopetrosis infantil maligna. El plan de tratamiento incluyó secuestrectomía y exondoncia de los dientes superiores erupcionados. Ningún procedimento quirúrgico se ha comprobado que sea superior a otros en la prevención del avance de infecciones bucales. Tomando en cuenta las condiciones generales del paciente al desarrollar osteomielitis refractaria y sintomática severa, la cirugía debe ser considerada. El paciente y sus familiares deben ser conscientes de los riesgos y beneficios de la cirugía, así como de sus posibles complicaciones.

Considered a rare inherited skeletal disease, osteopetrosis is characterized by a considerable increase in bone density resulting in defective remodeling, caused by failure in the normal function of osteoclasts, ranging in severity.1 According to its severity it and can be asymptomatic to fatal2 and it is often diagnosed by radiographic exams3, not being essential a bone biopsy.4

It is usually subdivided into three types: benign autosomal dominant osteopetrosis; intermediate autosomal recessive osteopetrosis; and malignant autosomal recessive infantile osteopetrosis (MIOP), considered the most serious type. This is associated with a decreased life expectancy, with most children dying in the second decade of life with complications of bone marrow suppression.1

MIOP is a rare recessive disorder characterized by dense, sclerotic, fragile, radio-opaque bones; neurological abnormalities; anemia and thrombocytopenia with subsequent extramedullary hematopoiesis and impaired vision and hearing caused by encroachment of the foramina and nerve canals.5 Infants are diagnosed with this form of OP immediately or shortly after birth. These patients often have pathological fractures, osteomyelitis of long bones and repeated rate of infections.6

Some differential diagnosis to consider include fluorosis; beryllium, lead and bismuth poisoning; myelofibrosis; Paget's disease (sclerosing form); and malignancies (lymphoma, osteoblastic cancer metastases).7

The development of dentition is severely disturbed in children with OP. Dental findings include delayed tooth eruption and impaction, aplasia, unerupted malformed tooth, enamel hypoplasia and early tooth loss.6,8

Regarding patients with osteopetrosis, osteomyelitis is the most common and well documented maxillofacial complication and can be severe and difficult to treat.2,3 We describe a case of chronic osteomyelitis in the maxilla of a patient with Malignant Infantile Osteopetrosis (MIOP).

Case reportA 6-year-old female patient, daughter of consanguineous phenotypically normal parents (cousins), attended the Maxillofacial Surgery Department of a hospital in Cuiabá (Mato Grosso, Brazil) accompanied by her grandmother with the story of fall from own height, hitting her mouth on the ground, resulting in the avulsion of two upper incisors. After 15 months, the wound had not healed.

In the interview, it was found that at birth the child was diagnosed with normocytic and normochromic anemia, needing transfusion every 15 days. In the first year of life she was diagnosed with MIOP.

On physical examination it was found that her height, weight and facial appearance were not in accordance with her chronological age. She presented distended abdomen with no soreness to palpation (Fig. 1). Percussion revealed a massive sound at the space Traube and hepatosplenomegaly. The spleen reached the region of the left iliac fossa across the median line. The liver reached the region of the iliac fossa on the right side. The surface was hard, smooth, regular edges and blunt. Genu valgus was observed (Fig. 2). Patient also had hearing loss.

Her face showed prominent frontal bossing and erythematous stain on the left infraorbital region (Fig. 3). On intraoral examination, it was noticed exposed bone with necrotic area in the anterior maxilla, diagnosed as chronic osteomyelitis (Fig. 4).

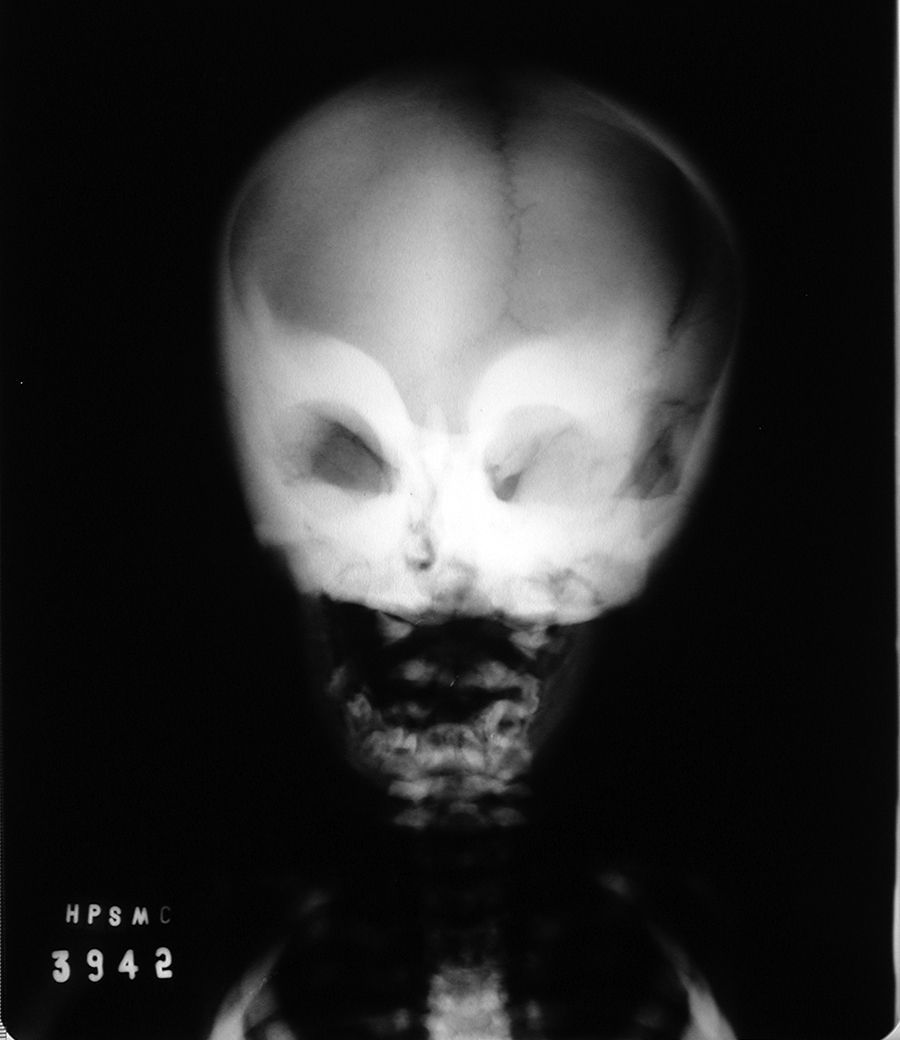

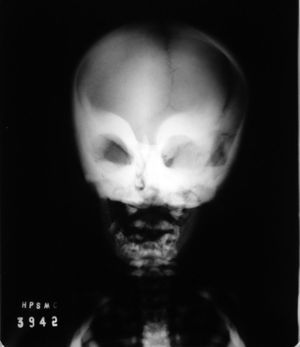

AP radiograph of face showed a more intense radiopacity of cortical bone of periorbital region and maxilla (Fig. 5). Chest radiography revealed intense radiopacity in the ribs and vertebrae, failing to distinguish between cortical and cancellous bone and intense radiopacity in the liver region, suggesting hepatomegaly.

Treatment plan included pre-maxilla sequestrectomy and extraction of erupted upper teeth. Patient was followed for five years with no wound healing (Fig. 6). The palliative care came to be, and patient died at age 11 from complications of osteopetrosis.

DiscussionOsteopetrosis is an inherited autosomal recessive skeletal dysplasia with still unidentified origin. Approximately 20% of cases derive from consanguineous marriages, affecting both genders, predominantly in caucasians.9

MIOP is characterized by progressive increase of bone density due to changes in function of the osteoclasts. It is transmitted by autosomal recessive inheritance, with unknown real incidence, ranging from 1:500,0003 to 1:100,000 newborns.1 It usually starts in utero and is diagnosed in the first year after birth. MIOP manifests clinically with increased bone fragility and pathological fractures, failure to thrive and frequent infections.3 Other organs may be affected as liver and spleen due to extramedullar hematopoiesis. Adenopathy, anemia, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia may also be associated.5 In addition, hydrocephalus, blindness, nystagmus, papilledema, proptosis, ocular paresis and deafness have been reported.3 Oral findings include retained and malformed teeth,4 mucositis, caries, periodontal problems.10

Osteomyelitis is a common complication in MIOP patients.2,3,10 Blood perfusion to the bone affected by the obliteration of medullary spaces7 combined with granulocytopenia, anemia and ischemia,2 commonly lead to necrosis and osteomyelitis.2,11 In these patients, osteomyelitis usually has odontogenic origin,10 but can also occur after trauma,11 as in this case.

Medical management of osteopetrosis is based on efforts to stimulate host osteoclasts on provide in alternate source of osteoclasts. Stimulation of host osteoclasts has been attempted with calcium restriction, calcitriol, steroids, parathyroid hormone and interferon. Hyperbaric oxygen has been used in the treatment of mandibular osteomyelitis. Bone marrow transplant has been used with cure for infantile malignant osteopetrosis. If untreated, infantile osteopetrosis usually results in death by the first decade of life due to severe anemia, bleeding or infection. Osteomyelitis secondary to osteopetrosis tends to be refractory because of the reduced blood supply and accompanying anemia and neutropenia. Surgical resection should be planned with caution as osteopetrotic bone has less capacity to heal12 and these children are at risk of adverse respiratory events and increased perioperative morbidity and mortality as anesthetic complications.13,14

Surgical treatment is indicated in cases of chronic osteomyelitis since the strict use of antibiotics will not reach the affected area due to compromised blood perfusion.15 The surgical procedure can vary from a simple curettage to complete bone resection, but patients treated with resection showed better results in long term and remained asymptomatic for long periods.11 Sequestrectomy is often necessary and should be accompanied by primary closure of soft tissue.3 In the reported case, sequestrectomy was chosen to allow reperfusion in the affected areas, allowing the host immune response, as well as drug therapy to reach the underlying infectious process. Furthermore, it is known that, at each operation, the ability to cure patients with osteopetrosis is reduced due to primary blood supply of the periosteum that once minimally disturbed, becomes impaired.3

The reconstruction after bone resection in patients with OP is extremely challenging and may be the main reason for a more conservative approach.2,3 In our case, there was no time to attempt a reconstruction, as the patient died before offering mature enough bone for this procedure.

ConclusionTreatment of osteomyelitis in patients with infantile osteopetrosis is still challenging. No surgical procedure was proven the best to prevent the progression of oral infection taking into account the patient's general condition. However, when the patient developed severe symptomatic and refractory osteomyelitis, the surgeon should consider a resection in attempt to remove most of the infected bone. It is also essential that the patient and his family are aware of the risks and benefits of surgery and its possible complications.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

FundingThe manuscript has no external financial support.

ConsentThe case report was approved by the Ethics Committee of Paulista University (643/09). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.