The objective of this paper is twofold: firstly, to analyse if there are differences between students’ motivation and their learning strategies when they study accounting subjects in Spanish or English as a medium of instruction. Secondly, to evidence the factors that mainly influence students’ total motivation. The Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) was carried out on a sample of 368 undergraduate students of a Business Administration Degree, in several accounting subjects taught in English and in Spanish. Multivariate statistical tests were run and interesting results have been found. Students who study a degree in English have more mature learning strategies and motivation than their counterparts. This is shown in their level of self-confidence, time study management and perseverance.

El objetivo de este trabajo es doble: en primer lugar, analizar si existen diferencias en la motivación y las estrategias de aprendizaje entre los alumnos que estudian asignaturas de contabilidad en español o en inglés. En segundo lugar, investigar los principales factores que afectan a la motivación total de los estudiantes. El cuestionario Motivación y Estrategias de Aprendizaje (MSLQ) fue aplicado a una muestra de 368 alumnos del grado de Administración y Dirección de Empresas en varias asignaturas de contabilidad que se impartieron en inglés y en español. Se llevaron a cabo análisis estadísticos multivariantes y se encontraron resultados interesantes. El alumnado que estudia un grado en inglés tiene mejores estrategias de aprendizaje y más motivación que sus compañeros que estudian en español. Esto se ve reflejado en su mayor nivel de autoestima, mejor gestión del tiempo de estudio y mayor perseverancia.

Higher Education Internationalisation (HEI) in the 21st century has new economic and social demands. International academic and professional talent attraction and retention have a common element – English as the medium of instruction and communication. One of the main challenges of HEI is to design and implement a bilingual strand or English as a Medium of Instruction (EMI) course. However, before HEI embraces and develops EMI programmes, it should be ascertained if there is sufficient demand and motivation among the students of EMI courses for it to be a success (Lueg & Lueg, 2015).

There is much research analysing motivation and learning strategies in students enrolled in different courses, following different lecturer methodologies or using different multimedia resources (Abeysekera and Dawson, 2015; Morales, Hernandez, Barchino, & Medina, 2015; Zlatovic, Balaban, & Kermek, 2015), but it is scarce when analysing if there are different motivation and learning strategies among students from EMI versus non-EMI courses (Dafouz, Camacho, & Urquia, 2014). This issue is important in HEI because a causal relationship is assumed between better learners, deep learning and subsequent professional work in real life. Students motivated to learn are interested in the issues included in lectures, reading and research and therefore try to complete more exercises and work harder (Camacho-Miñano & Del Campo, 2015). Therefore, possessing better learning strategies will be essential for achieving higher learning performance (Montagud & Gandía, 2014). Educational research endeavours to discover the ideal student learning strategies in order to promote them. Additionally, understanding student motivation and learning strategies is fundamental in order to help university lecturers develop better teaching practices (Arquero, Byrne, Flood, & González, 2009; Arquero, Byrne, Flood, & González, 2015).

Motivation refers to students’ specific motivation towards a particular class, task, or content area at a given moment; it can vary from time to time (Brophy, 1986; Brophy, 1987; Keller, 1983). It may also refer to student's general motivation towards studying or learning (Frymier, 1994). It is not enough if students are motivated to achieve better marks, as learning strategies are also essential for achieving high grades (Ames & Archer, 1988). Motivated students should achieve good academic results. Unfortunately, this is not the case if they fail to adopt good learning strategies. Prior literature evidenced that more motivated students tended to use better strategies than less motivated students (Oxford, 1994). However, although there is research about motivation towards studying in English (Karlak & Velki, 2015) or in an EMI context (Kirkgöz, 2005) there is scarce research analysing the differences between motivation and learning strategies of EMI students compared with their non-EMI peers.

Together with motivation, students’ learning strategies have an important role in the learning process. Learning strategies could be defined as thoughts or behaviours used by students in order to acquire, understand or learn new knowledge (Cano, 2006). In 1991 Pintrich et al. designed and implemented a Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ). The MSLQ is a Likert-scaled instrument that was designed to assess motivation and use of learning strategies of college students. It divides motivation into three main areas: firstly, motivation including intrinsic and extrinsic goal orientation and task value; secondly, the expectation measured by control beliefs about learning and self-efficacy and, thirdly, the affection or anxiety test. In parallel, learning strategies comprise cognitive, meta-cognitive, and resource management strategies. Cognitive strategies include rehearsal, elaboration, organisation, and critical thinking. Meta-cognitive strategies include planning, monitoring, and regulating strategies. Resource management strategies comprise managing time and study environment; effort management, peer learning, and help-seeking.

The objective of this paper is twofold: firstly, to analyse if there are differences between students’ motivation and their learning strategies when they study accounting subjects in English or Spanish as a medium of instruction. Secondly, to evidence the factors that mainly influence students’ total motivation. Given the scope of our research, we have decided to use a shortened MSLQ questionnaire in line with Pintrich (2004), focusing on the motivation scale in “self-efficacy for learning and performance” items and for learning strategies in three scales: “metacognitive self-regulation”, “time-study environmental management” and “effort regulation”. All these scales refer to the students’ self-regulatory perspective. We have decided to use these items for our research because they are dynamic aspects that can be modified and improved by students and lecturers in different learning contexts.

The shortened MSLQ questionnaire was carried out on a sample of 368 undergraduate students of a Business Administration Degree taught in English and in Spanish at several universities. Descriptive and multivariate statistical tests were run. The main finding of this paper is that EMI students are, on average, more motivated and use better learning strategies than their counterparts. Concretely, EMI students are more self-confident and perseverant, showing better study time management and effort. Variables such as gender, university access grade and learning strategies as methodology, perseverance and reflectiveness affect motivation for learning. We would also like to highlight the benefits and value derived from the collaboration and sharing between the four lecturers belonging to three different universities that took part in this project.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Firstly, we provide an overview of the existing literature regarding motivation and learning strategies. Secondly, we describe the objectives of this paper and the sample and methodology used are presented. Finally, we comment on certain results that give rise to interesting conclusions.

Motivation and learning strategies literatureIn the Higher Education context there exists diverse research on students motivation, taking into account intrinsic and extrinsic goal orientation; expectancy about learning and self-efficacy and affection or test anxiety (Pintrich, Smith, García, & McKeachie, 1991). Students need to use motivation to deal with obstacles and complete the learning process, complying with academic and social expectations (Corno, 2001). Thus, the issue of motivation in general plays a vital role in the learning process. Specifically, it relates to becoming involved in academic tasks in terms of higher levels of cognitive and regulatory strategy use (Eccles & Wigfield, 1995; Wigfield and Eccles, 1992). In this process, the student considers the importance of doing a specific task well, the personal interest in the task content and its usefulness in relation to future personal goals. High task value beliefs activate the students’ effort and time invested and, consequently, their cognitive engagement through the application of “deep” cognitive and metacognitive strategies (McWhaw and Abrami, 2001; Schiefele, 1991). Thus, motivation is not only related to the initiation of the learning process, but was found to also indirectly influence performance, by means of cognitive engagement through the application of strategies. Pintrich and De Groot (1990), as well as other researchers, have analysed the complex relationship between motivation and learning-goals achievement. It has also been found that students form motivational beliefs towards different specific concrete content or can be generalised across various academic fields (Anderman, 2004; Bong, 2001, 2004; Wigfield, Guthrie, Tonks, & Perencevich, 2004; Wolters & Pintrich, 1998). Despite, the importance of expectancy and self-efficacy, a careful examination of the relevant literature reveals that the majority of empirical research has focused more on the area of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for different subject areas (Brophy, 2008). Furthermore, studies in this framework found differences in motivation and strategic behaviour across different subject areas (Wolters & Pintrich, 1998).

Motivation and learning strategies are very much interrelated concepts (Cohen & Dörnyei, 2002; Dörnyei & Skehan, 2003). As motivation comprises effort as a behavioural component (Gardner, 1985, 1988), it has been demonstrated that more successful learners use more active appropriate learning strategies, this being a reflection of their motivation to learn (Dörnyei, 1996). Griffiths (2003) confirms that the more successful learners, who are more motivated, use more interactive and sophisticated strategies in comparison with the less successful learners. Furthermore, Wong and Nunan (2011) find that the more successful learners are significantly more autonomous and active in learning. Conversely, less successful learners are characterised by using learning strategies which are more dependent on authority, such as the teacher and the textbook. Previous research in the expectancy area indicates that academic choices, the degrees of engagement and achievement are predicted by a combination of students’ competence beliefs, their interest, and the value they assign to a specific task or area (Eccles, Wigfield, & Schiefele, 1998).

Learning strategies can be defined as the different combinations of activities students use while learning, with greater variability over time or as any behaviours that facilitate the acquisition, understanding or later transfer of knowledge and skills (Weinstein, Husman, & Dierking, 2000) or as specific activities or techniques students use to improve their progress in apprehending and internalising concepts (Oxford, 2002). For her part, Chamot (2004) defines learning strategies as the thoughts and actions that learners take in order to achieve learning goals. An early taxonomy of learning strategies differentiated between strategies that operate directly on information (rehearsal, elaboration, and organisation) and strategies that provide affective and metacognitive support for learning (affective control strategies, and comprehension monitoring strategies). Interestingly, all authors coincide on the behavioural and conscious aspects in their definitions of learning strategies. Learners use the strategies deliberately, and for this reason they can identify them. This is a key factor when trying to carry out a study on motivation and learning strategies because this acquired knowledge allows learners to report the strategies used, and, therefore, to control and improve their own learning approaches (Chamot, 2004; Grenfell & Macaro, 2007). In general, students’ learning strategies are developed in order to achieve learning goals, are dynamic in nature and can be developed within shorter periods (Zlatovic et al., 2015). Through their learning strategies, students can achieve a “deep learning approach” or a “surface learning approach”. The surface approach is the reproduction of learning content (memorisation of facts and data, mechanical substitutions in formulas, etc.). Understanding of learning content is either very low or non-existent. The deep approach means to understand learning content (questioning of alternatives, raising additional questions, exploration of the newly-learned content's application limits, etc.). Lecturers should therefore try to promote the correct learning strategies such as students’ own confidence in their academic performance (both in class and in the exams) in the subject, skills development and comprehension skills to achieve deep learning. Research is diverse when analysing the learning strategies developed by the students attending a classic lecture versus an innovative one, using the traditional books and slides versus multimedia on-line resources (Zlatovic et al., 2015), or the relationship between using different assessment methodologies (Pascual-Ezama, Camacho-Miñano, Urquia-Grande, & Müller, 2011). Other research initiated by Pintrich et al. (1991) analyses learning strategies classified in nine scales which can be divided into three main areas – cognitive, meta-cognitive, and resource management strategies. Further research links studies on motivation and learning strategies to psychological issues analysing the students’ perception of students’ learning strategies determining their academic performance (Loyens, Magda, & Rikers, 2008). Other empirical studies compare motivation and learning strategies towards different teaching resources used frequently by lecturers: Case versus lecture (Barise, 2000); multimedia (Liu, 2003); computer-based versus web-based (Eom & Reiser, 2000) and on-line teaching (Miltiadou, 2001; Zerbini, Abbad, Mourao, & Barros Martins, 2014; Zlatovic et al., 2015). Credé and Phillips (2011) carried out a meta-analysis with the results of 59 articles to analyse the link between the different scales of motivation and learning strategies being effort regulation, self-efficacy and time and study management the most highly linked. Self-regulated learning strategies have recently emerged as an important area, with the focus on the way in which students initiate, monitor, and exert control over their own learning (Winne, 1995; Zimmerman, 2000; Eom and Reiser, 2000; Boekaerts & Cascallar, 2006).

In parallel, another research trend is the analysis of differences in students’ motivation when choosing to learn their degree in a second language, where the importance of individual difference factors is stressed but has not completely clarified the connection between those factors (Karlak & Velki, 2015). Since previous research reveals that motivation for foreign and second language learning is a precondition for learning strategies usage in its personal and socio-cultural dimension, this can have a key role in predicting the students’ academic and personal success. Additionally, other language learning strategy research aimed to identify the strategies that learners use while learning in English as a second language (L2) (O’Malley & Chamot, 1990; Oxford, 1990). Recent research has devoted its attention to analysing the relationship between the use of language learner strategies and other learner variables such as age, the L2 proficiency level, the gender and motivation where the results vary greatly depending on the context, the participants or the instruments used (Dafouz et al., 2014; Lueg & Lueg, 2015). However, research is scarce when analysing students’ differences in terms of motivation and learning strategies in EMI versus non-EMI courses.

Bearing all these ideas in mind, we define the following research questions for our study:

- •

RQ1: Are there differences in motivation from EMI students versus non-EMI students of accounting subjects?

- •

RQ2: Are there differences in learning strategies from EMI versus non-EMI students of accounting subjects?

- •

RQ3: What are the factors that could influence students’ total motivation in accounting subjects?

The answers to these research questions could be a useful guideline for lecturers and universities when implementing EMI courses, as better motivated students tend to be better learners.

Sample description, instrument and methodologyThe instrument: MSLQ (Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire)The MSLQ was designed by Pintrich et al. (1991) to be used by researchers as an instrument to ascertain the nature of student motivation and learning strategies, and to be used by instructors and students as a means of assessing students’ motivation and study skills. It was developed using a social-cognitive view of motivation and self-regulated learning strategies. This framework assumes that motivation and learning strategies are not static traits of the learner, but rather that “motivation is dynamic and learning strategies can be learned and brought under the student's control” (Duncan & McKeachie, 2005). In addition, a student's motivation can change from course to course (e.g., depending on the interest in the course, special abilities, etc.), and his or her learning strategies may vary as well, depending on the nature of the course.

The MSLQ is a questionnaire with 81 questions. 31 of which deal with motivation, which is divided into three scales: Firstly, intrinsic and extrinsic goal orientation and task value; secondly, the expectancy measured by control beliefs about learning and self-efficacy and thirdly, the affection or test anxiety. The learning strategies section is composed of 50 questions, organised into three main areas: cognitive (19), meta-cognitive (12) and resource management strategies (19). The cognitive strategies scales include rehearsal, elaboration, organisation, and critical thinking. Meta-cognitive strategies are assessed by one large scale that includes planning, monitoring, and regulating strategies. Resource management strategies include managing time and study environment; effort management, peer learning, and help seeking. All scale reliabilities are robust where confirmatory factor analyses demonstrated good factor structure. It usually takes around 30min to complete the full questionnaire.

According to Cardozo (2008) and Pintrich et al. (1993), the questionnaire's areas can be used independently in relation to the purpose of the study. Consequentially, several authors have used part of this questionnaire to analyse some specific issues within student academic performance (Bong, 2001; Campbell, 2001; Loyens et al., 2008, Dafouz et al., 2014) or lingüistic competences (Karlak & Velki, 2015).

From the beginning, the MSLQ questionnaire has been used and validated by several academic researchers in order to link assessment with students’ preferences and learning styles (Angelo & Cross, 1993; Cano, 2006; Seymour, Wiese, Hunter, & D, 2000; Weinstein et al., 2000; Zimmerman & Martinez-Pons, 1988). For example, Dunn et al. (2009) analysed 12 items of meta-cognitive self-regulation and four items regarding effort regulation with a sample of 355 students, generating at the same time another questionnaire named ‘general strategies for learning scales and clarification strategies for learning scales’. Other researchers have used MSLQ in psychological studies using the self-regulated learning part of the questionnaire. Others have run MSLQ questionnaire on school students basically to test mathematics learning strategies (Metallidou & Vlachou, 2010). In addition, the instrument shows reasonable predictive validity in students’ performance demonstrated by several authors (Artino, 2009; Boekaerts & Corno, 2005; Cardozo, 2008).

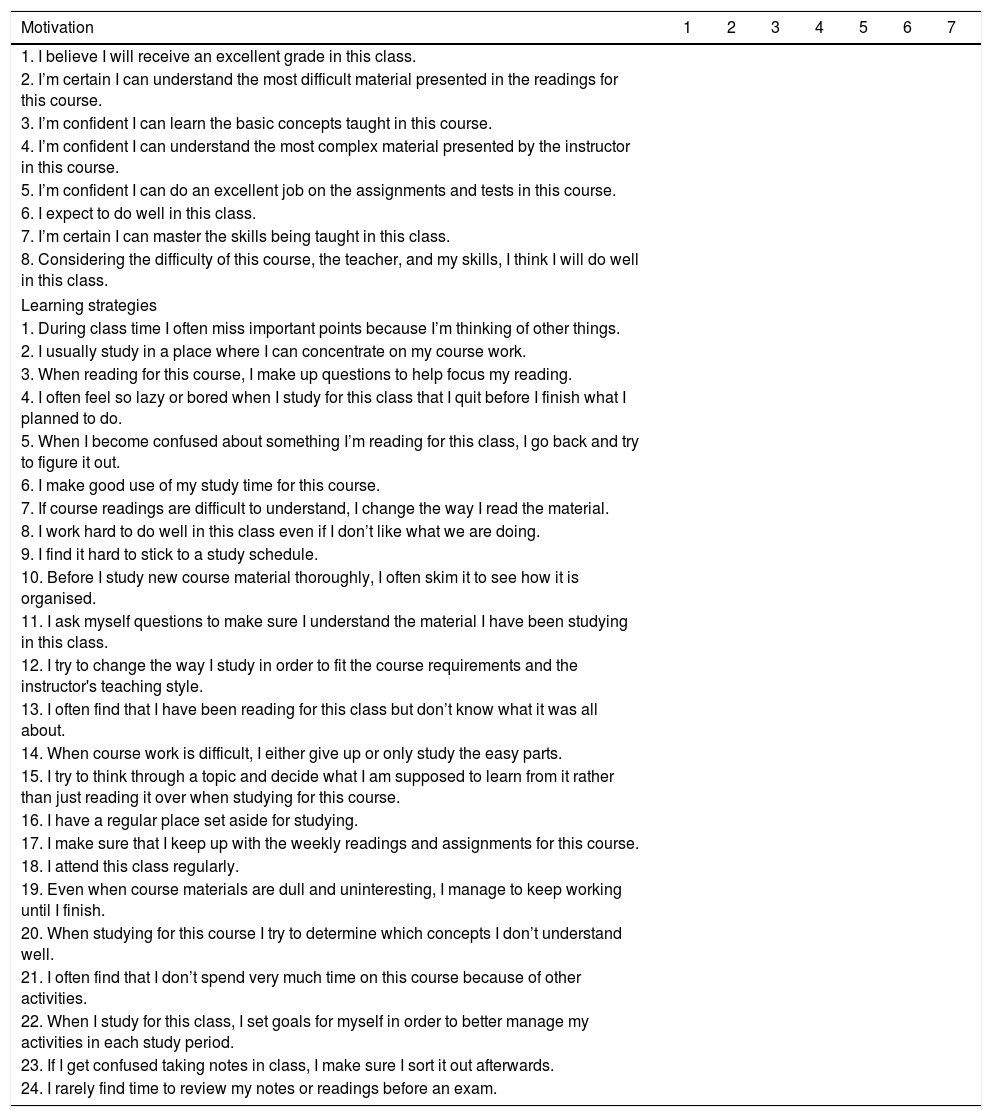

In summary, many empirical studies have successfully used MSLQ for different purposes and the questionnaire has been validated by many research studies. This is the reason for choosing the MSLQ questionnaire to compare motivation and learning strategies between EMI and non-EMI students. In this research paper we have decided to shorten the questionnaire and focus on the intrinsic motivation questions (8 items) and on two learning strategy areas (24 items). The reason for choosing these scales is that these are the ones that we can work with, given that they are dynamic and can be modified and improved in different learning contexts. For measuring “motivation” we have chosen the 8 questions related to students’ “Self-Efficacy for Learning and Performance”. The items comprising this scale assess two aspects of expectancy: expectancy for success and self-efficacy. Expectancy for success refers specifically to task performance, whilst self-efficacy is a self-appraisal of one's ability to master a task.

In relation to learning strategies, we have selected 24 “learning strategies” in the areas we consider are more related with self-efficacy, in line with Boekaerts and Corno (2005) and Metallidou and Vlachou (2010). We have chosen the metacognitive self-regulation questions (12), time-study environmental management (8) and effort regulation (4) (see Annex). The metacognitive self-regulation questions refer to awareness, knowledge and control cognition. We are more interested in the control and self-regulation aspects such as planning, monitoring and regulating. Planning helps to organise and comprehend the material more easily. Regulating activities help to improve performance. Time-study management involves scheduling, planning and managing one's study time effectively. Study environmental management refers to the setting where the student does his/her class work ideally a quiet place free of distractions. Effort management refers to the commitment to complete goals even when faced with difficulties.

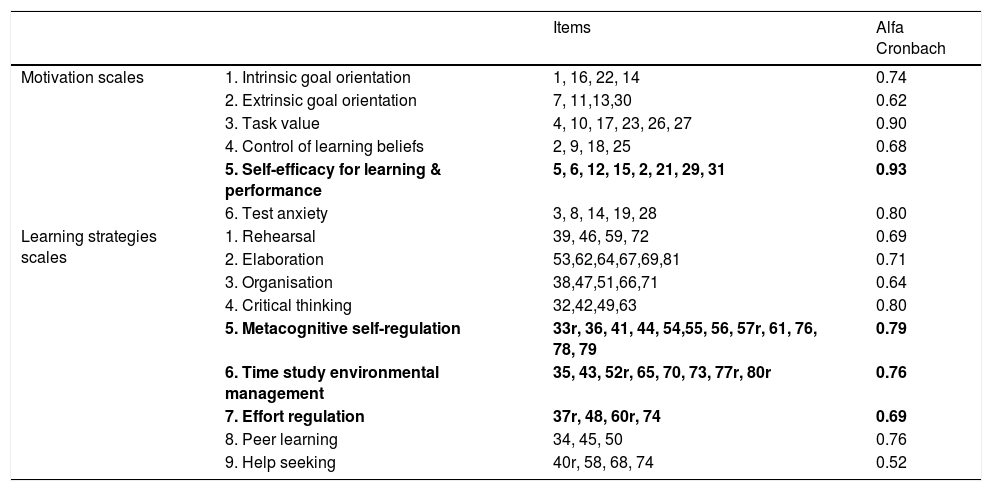

A summary of the full questionnaire is shown in Table 1. In bold are shown the items included in the questionnaire. Some of these questions are negatively worded or reverse-coded (indicated in Table 1 as “r”) which means they have to be reversed before a student's score is computed. The way to insert a reverse-coded item in the database is to take the original score and subtract it from 8 (Pintrich et al., 1991). The Cronbach's alphas of all the selected questions are in the range of 0.7 to 0.93, showing a strong internal consistency and reliability of the questionnaire. The participants are requested to rate themselves on a 7-point scale, for each of the questions from 1 (not at all true of me) to 7 (very true of me).

MSLQ questionnaire: different areas and validity.

| Items | Alfa Cronbach | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation scales | 1. Intrinsic goal orientation | 1, 16, 22, 14 | 0.74 |

| 2. Extrinsic goal orientation | 7, 11,13,30 | 0.62 | |

| 3. Task value | 4, 10, 17, 23, 26, 27 | 0.90 | |

| 4. Control of learning beliefs | 2, 9, 18, 25 | 0.68 | |

| 5. Self-efficacy for learning & performance | 5, 6, 12, 15, 2, 21, 29, 31 | 0.93 | |

| 6. Test anxiety | 3, 8, 14, 19, 28 | 0.80 | |

| Learning strategies scales | 1. Rehearsal | 39, 46, 59, 72 | 0.69 |

| 2. Elaboration | 53,62,64,67,69,81 | 0.71 | |

| 3. Organisation | 38,47,51,66,71 | 0.64 | |

| 4. Critical thinking | 32,42,49,63 | 0.80 | |

| 5. Metacognitive self-regulation | 33r, 36, 41, 44, 54,55, 56, 57r, 61, 76, 78, 79 | 0.79 | |

| 6. Time study environmental management | 35, 43, 52r, 65, 70, 73, 77r, 80r | 0.76 | |

| 7. Effort regulation | 37r, 48, 60r, 74 | 0.69 | |

| 8. Peer learning | 34, 45, 50 | 0.76 | |

| 9. Help seeking | 40r, 58, 68, 74 | 0.52 |

In bold the groups of items chosen to answer our research questions.

Source: Own source inspired in Pintrich et al. (1991), Pintrich (2004) and Cardozo (2008).

The questionnaire took place in the classroom during an accounting lecture at the end of 2015–2016 academic year. Previously, the instructor explained the objective of the research and the procedure. The parts of the questionnaire were explained, pointing out the importance of their collaboration. The questionnaire was completed by hand and was carried out on an entirely voluntary basis. However, all students opted to take part. Filling out the questionnaire lasted no longer than 20min.

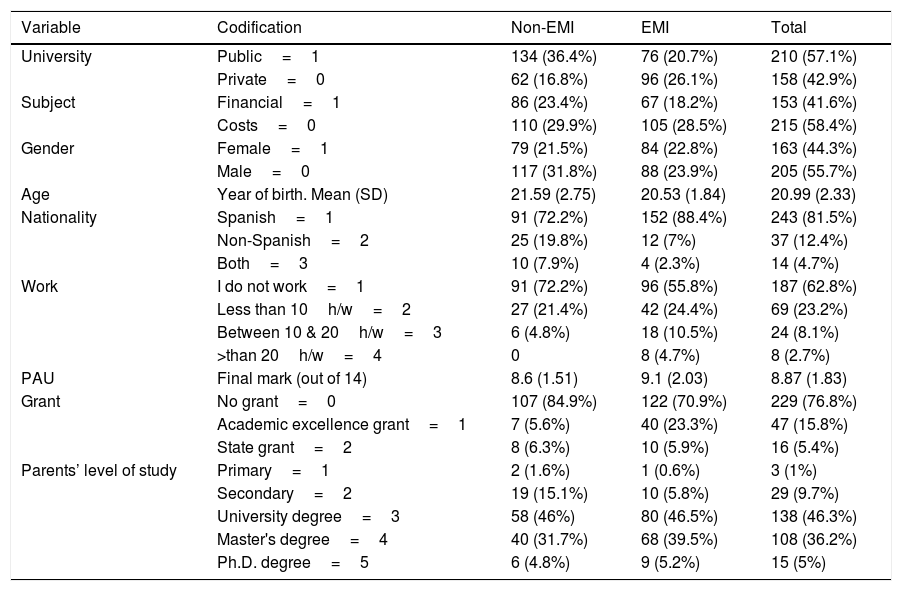

The sampleThe sample comprised 368 students from three different universities in Madrid, all of them studying the Business Administration Degree. It was separated into EMI and non-EMI students. We consider the sample to be representative and balanced, since 172 students (47%) belong to the EMI strand and 196 (53%) to the non-EMI strand. Regarding the type of university, 210 students (57.1%) were from a public university, Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM) and 158 (42.9%) from two private universities. Colegio Universitario de Estudios Financieros (CUNEF) and Universidad Francisco de Vitoria (UFV). The questionnaire was given to students of Financial Accounting 41.6% and Cost and Management Accounting 58.4%. These subjects belong to the first and the second years of the Bachelor Degree in Business Administration, when lecturers have more options to interact and motivate them as they are at the beginning of their university studies.

General descriptive data of participants was collected. It includes information regarding gender, age, nationality, work, university access grades, if they have a grant and their parents’ education. In Table 2 we show all descriptive variables and its codification for both EMI and non-EMI students.

Basic descriptive statistics and variable codifications.

| Variable | Codification | Non-EMI | EMI | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| University | Public=1 | 134 (36.4%) | 76 (20.7%) | 210 (57.1%) |

| Private=0 | 62 (16.8%) | 96 (26.1%) | 158 (42.9%) | |

| Subject | Financial=1 | 86 (23.4%) | 67 (18.2%) | 153 (41.6%) |

| Costs=0 | 110 (29.9%) | 105 (28.5%) | 215 (58.4%) | |

| Gender | Female=1 | 79 (21.5%) | 84 (22.8%) | 163 (44.3%) |

| Male=0 | 117 (31.8%) | 88 (23.9%) | 205 (55.7%) | |

| Age | Year of birth. Mean (SD) | 21.59 (2.75) | 20.53 (1.84) | 20.99 (2.33) |

| Nationality | Spanish=1 | 91 (72.2%) | 152 (88.4%) | 243 (81.5%) |

| Non-Spanish=2 | 25 (19.8%) | 12 (7%) | 37 (12.4%) | |

| Both=3 | 10 (7.9%) | 4 (2.3%) | 14 (4.7%) | |

| Work | I do not work=1 | 91 (72.2%) | 96 (55.8%) | 187 (62.8%) |

| Less than 10h/w=2 | 27 (21.4%) | 42 (24.4%) | 69 (23.2%) | |

| Between 10 & 20h/w=3 | 6 (4.8%) | 18 (10.5%) | 24 (8.1%) | |

| >than 20h/w=4 | 0 | 8 (4.7%) | 8 (2.7%) | |

| PAU | Final mark (out of 14) | 8.6 (1.51) | 9.1 (2.03) | 8.87 (1.83) |

| Grant | No grant=0 | 107 (84.9%) | 122 (70.9%) | 229 (76.8%) |

| Academic excellence grant=1 | 7 (5.6%) | 40 (23.3%) | 47 (15.8%) | |

| State grant=2 | 8 (6.3%) | 10 (5.9%) | 16 (5.4%) | |

| Parents’ level of study | Primary=1 | 2 (1.6%) | 1 (0.6%) | 3 (1%) |

| Secondary=2 | 19 (15.1%) | 10 (5.8%) | 29 (9.7%) | |

| University degree=3 | 58 (46%) | 80 (46.5%) | 138 (46.3%) | |

| Master's degree=4 | 40 (31.7%) | 68 (39.5%) | 108 (36.2%) | |

| Ph.D. degree=5 | 6 (4.8%) | 9 (5.2%) | 15 (5%) |

Male participants were more numerous than females (205 versus 163). The age mean is very similar in both groups – around 21 years old. In relation to nationality, 81.5% of our students are Spanish. In relation to students carrying out paid work at the same time they study, most of our students do not work (62.8%) or work very few hours a week – mostly at the weekend (23.2%). The exam to university access grade was 9.1 out of 14 among EMI students versus 8.6 for non-EMI students. Regarding grants, most of our students (76.8%) do not receive any financial support, although more EMI students than non-EMI receive grant (29.2% vs. 11.9%).

In general, 87.5% of parents have higher education, although EMI student parents’ education is higher than non-EMI. 44.7% of EMI parents have a master or doctorate versus 36.5% from non-EMI students’ parents.

MethodologyStatistical methods were used to help answer our research questions. We started with variance analysis (ANOVA) to study the differences in motivation (RQ1) and learning strategies (RQ2) among group means and between groups. In addition, factor analysis is used to identify joint variations in response to unobserved latent variables. Factor analysis originated in psychometrics is used in the social sciences and other fields that deal with data sets where there are large numbers of observed variables. The purpose is to reduce the number of variables, thereby producing a smaller number of underlying/latent variables. Finally, a regression analysis was carried out to analyse the factors that could influence students’ total motivation in accounting subjects (RQ3).

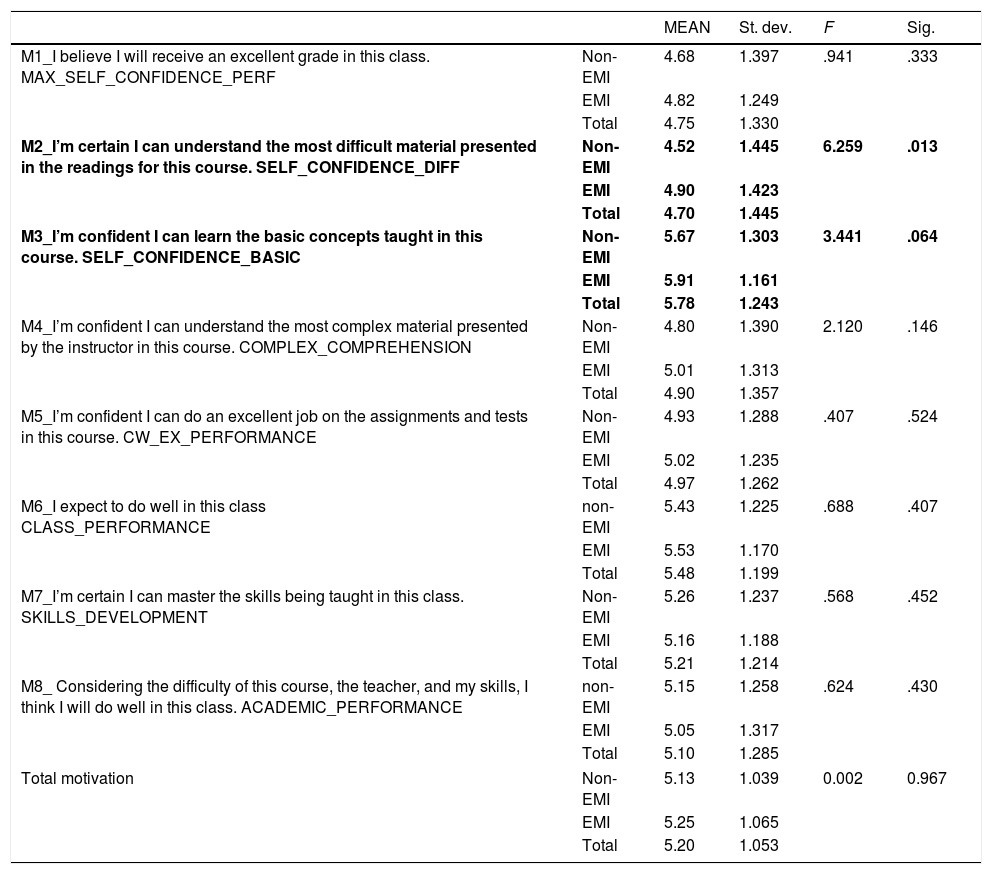

Findings and discussionThe results of the ANOVA test provide a statistical test of whether or not the average of several groups is equal and it is also useful for identifying statistically significant differences when comparing EMI and non-EMI students’ motivation and learning strategies. Looking at motivation (RQ1), results have shown that it is higher in EMI students compared with non-EMI students, with statistically significant differences in two items: understanding basic and difficult concepts in Accounting. Specifically, EMI students are more self-confident in understanding basic concepts (5.91 versus 5.67) and in learning difficult accounting issues (4.90 versus 4.52) (see Table 3). This finding is in line with Lueg and Lueg (2015), who highlight that EMI students have more self-confidence than non-EMI students. This can be associated with a higher level of education and social recognition, as we can see in their better university access grades and their parents’ education. It is interesting to highlight that the EMI students’ self confidence in understanding basic concepts in Accounting is the highest valued among all the motivation questions. Although there are no statistically significant differences in general, EMI students are more motivated and confident in performing optimally in accounting subjects when asked about their expectations in achieving an excellent mark in the coursework, the exams and even in class. According to these results, it would be interesting in future research to analyse how to improve students’ self-confidence in early stages of higher education.

Students’ motivation differences.

| MEAN | St. dev. | F | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1_I believe I will receive an excellent grade in this class. MAX_SELF_CONFIDENCE_PERF | Non-EMI | 4.68 | 1.397 | .941 | .333 |

| EMI | 4.82 | 1.249 | |||

| Total | 4.75 | 1.330 | |||

| M2_I’m certain I can understand the most difficult material presented in the readings for this course. SELF_CONFIDENCE_DIFF | Non-EMI | 4.52 | 1.445 | 6.259 | .013 |

| EMI | 4.90 | 1.423 | |||

| Total | 4.70 | 1.445 | |||

| M3_I’m confident I can learn the basic concepts taught in this course. SELF_CONFIDENCE_BASIC | Non-EMI | 5.67 | 1.303 | 3.441 | .064 |

| EMI | 5.91 | 1.161 | |||

| Total | 5.78 | 1.243 | |||

| M4_I’m confident I can understand the most complex material presented by the instructor in this course. COMPLEX_COMPREHENSION | Non-EMI | 4.80 | 1.390 | 2.120 | .146 |

| EMI | 5.01 | 1.313 | |||

| Total | 4.90 | 1.357 | |||

| M5_I’m confident I can do an excellent job on the assignments and tests in this course. CW_EX_PERFORMANCE | Non-EMI | 4.93 | 1.288 | .407 | .524 |

| EMI | 5.02 | 1.235 | |||

| Total | 4.97 | 1.262 | |||

| M6_I expect to do well in this class CLASS_PERFORMANCE | non-EMI | 5.43 | 1.225 | .688 | .407 |

| EMI | 5.53 | 1.170 | |||

| Total | 5.48 | 1.199 | |||

| M7_I’m certain I can master the skills being taught in this class. SKILLS_DEVELOPMENT | Non-EMI | 5.26 | 1.237 | .568 | .452 |

| EMI | 5.16 | 1.188 | |||

| Total | 5.21 | 1.214 | |||

| M8_ Considering the difficulty of this course, the teacher, and my skills, I think I will do well in this class. ACADEMIC_PERFORMANCE | non-EMI | 5.15 | 1.258 | .624 | .430 |

| EMI | 5.05 | 1.317 | |||

| Total | 5.10 | 1.285 | |||

| Total motivation | Non-EMI | 5.13 | 1.039 | 0.002 | 0.967 |

| EMI | 5.25 | 1.065 | |||

| Total | 5.20 | 1.053 | |||

The bold text shows significant coefficients at 10%.

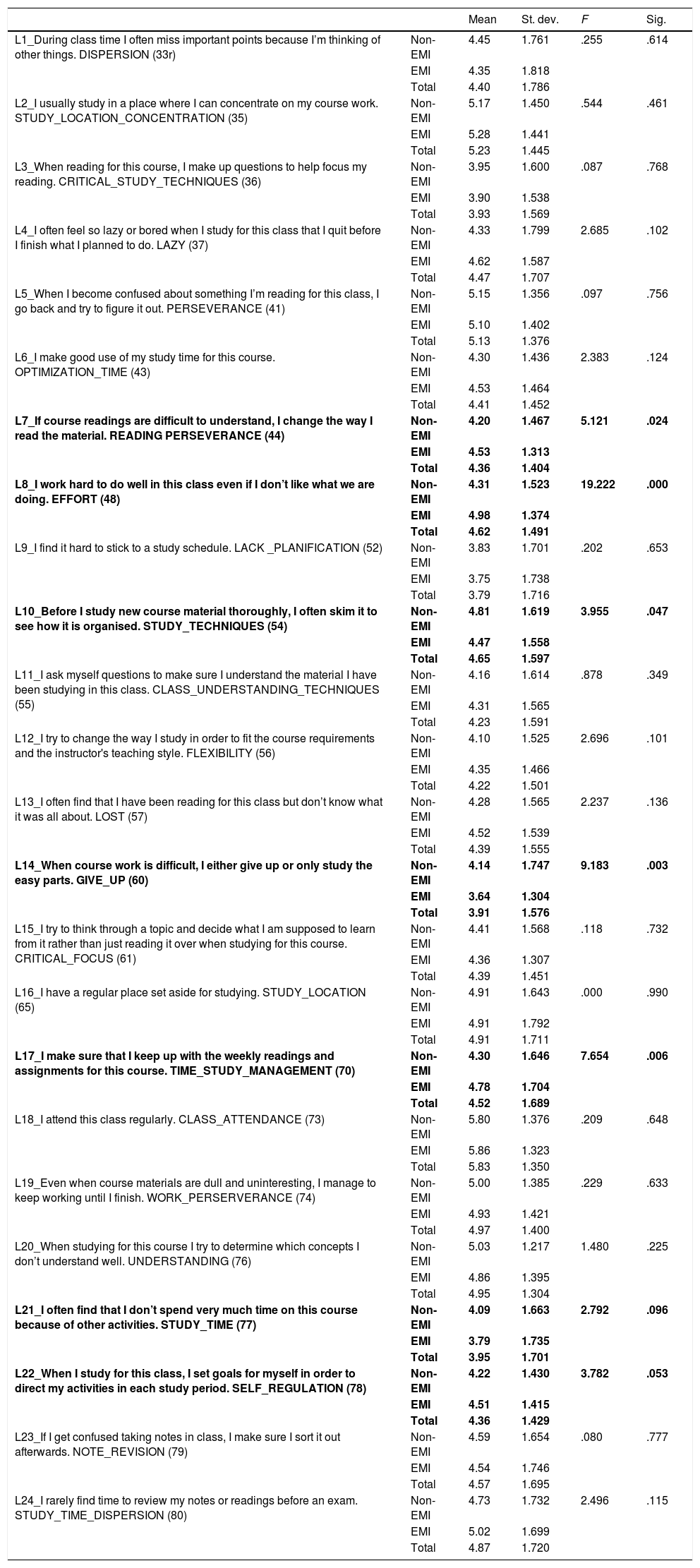

Within learning strategies (RQ2), statistically significant differences appear between EMI and non-EMI students in four items. EMI students score higher in L-8; effort (4.98 versus 4.31); L-17; time-study management (4.78 versus 4.30) and L-7; reading perseverance (4.53 versus 4.20). Finally, EMI students set organisation goals; L-22 (4.51) better than their counterparts (4.22) (see Table 4). Effort reflects a commitment to complete their study goals even when there are difficulties or distractions. This is the variable which has the most significant difference among EMI versus non-EMI students, in the same way as the results of Dafouz et al. (2014). Students’ time-study management is related to scheduling and planning tasks. Students’ reading perseverance refers to the fine-tuning and continuous adjustment of their cognitive activities. Hence, as EMI students have chosen to study in a foreign language, they are conscious of having to make an extra effort, working harder in class and are more perseverant readers, organising their study time and lecture readings better and not surrendering when faced with difficulty.

Students’ learning strategies differences.

| Mean | St. dev. | F | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1_During class time I often miss important points because I’m thinking of other things. DISPERSION (33r) | Non-EMI | 4.45 | 1.761 | .255 | .614 |

| EMI | 4.35 | 1.818 | |||

| Total | 4.40 | 1.786 | |||

| L2_I usually study in a place where I can concentrate on my course work. STUDY_LOCATION_CONCENTRATION (35) | Non-EMI | 5.17 | 1.450 | .544 | .461 |

| EMI | 5.28 | 1.441 | |||

| Total | 5.23 | 1.445 | |||

| L3_When reading for this course, I make up questions to help focus my reading. CRITICAL_STUDY_TECHNIQUES (36) | Non-EMI | 3.95 | 1.600 | .087 | .768 |

| EMI | 3.90 | 1.538 | |||

| Total | 3.93 | 1.569 | |||

| L4_I often feel so lazy or bored when I study for this class that I quit before I finish what I planned to do. LAZY (37) | Non-EMI | 4.33 | 1.799 | 2.685 | .102 |

| EMI | 4.62 | 1.587 | |||

| Total | 4.47 | 1.707 | |||

| L5_When I become confused about something I’m reading for this class, I go back and try to figure it out. PERSEVERANCE (41) | Non-EMI | 5.15 | 1.356 | .097 | .756 |

| EMI | 5.10 | 1.402 | |||

| Total | 5.13 | 1.376 | |||

| L6_I make good use of my study time for this course. OPTIMIZATION_TIME (43) | Non-EMI | 4.30 | 1.436 | 2.383 | .124 |

| EMI | 4.53 | 1.464 | |||

| Total | 4.41 | 1.452 | |||

| L7_If course readings are difficult to understand, I change the way I read the material. READING PERSEVERANCE (44) | Non-EMI | 4.20 | 1.467 | 5.121 | .024 |

| EMI | 4.53 | 1.313 | |||

| Total | 4.36 | 1.404 | |||

| L8_I work hard to do well in this class even if I don’t like what we are doing. EFFORT (48) | Non-EMI | 4.31 | 1.523 | 19.222 | .000 |

| EMI | 4.98 | 1.374 | |||

| Total | 4.62 | 1.491 | |||

| L9_I find it hard to stick to a study schedule. LACK _PLANIFICATION (52) | Non-EMI | 3.83 | 1.701 | .202 | .653 |

| EMI | 3.75 | 1.738 | |||

| Total | 3.79 | 1.716 | |||

| L10_Before I study new course material thoroughly, I often skim it to see how it is organised. STUDY_TECHNIQUES (54) | Non-EMI | 4.81 | 1.619 | 3.955 | .047 |

| EMI | 4.47 | 1.558 | |||

| Total | 4.65 | 1.597 | |||

| L11_I ask myself questions to make sure I understand the material I have been studying in this class. CLASS_UNDERSTANDING_TECHNIQUES (55) | Non-EMI | 4.16 | 1.614 | .878 | .349 |

| EMI | 4.31 | 1.565 | |||

| Total | 4.23 | 1.591 | |||

| L12_I try to change the way I study in order to fit the course requirements and the instructor's teaching style. FLEXIBILITY (56) | Non-EMI | 4.10 | 1.525 | 2.696 | .101 |

| EMI | 4.35 | 1.466 | |||

| Total | 4.22 | 1.501 | |||

| L13_I often find that I have been reading for this class but don’t know what it was all about. LOST (57) | Non-EMI | 4.28 | 1.565 | 2.237 | .136 |

| EMI | 4.52 | 1.539 | |||

| Total | 4.39 | 1.555 | |||

| L14_When course work is difficult, I either give up or only study the easy parts. GIVE_UP (60) | Non-EMI | 4.14 | 1.747 | 9.183 | .003 |

| EMI | 3.64 | 1.304 | |||

| Total | 3.91 | 1.576 | |||

| L15_I try to think through a topic and decide what I am supposed to learn from it rather than just reading it over when studying for this course. CRITICAL_FOCUS (61) | Non-EMI | 4.41 | 1.568 | .118 | .732 |

| EMI | 4.36 | 1.307 | |||

| Total | 4.39 | 1.451 | |||

| L16_I have a regular place set aside for studying. STUDY_LOCATION (65) | Non-EMI | 4.91 | 1.643 | .000 | .990 |

| EMI | 4.91 | 1.792 | |||

| Total | 4.91 | 1.711 | |||

| L17_I make sure that I keep up with the weekly readings and assignments for this course. TIME_STUDY_MANAGEMENT (70) | Non-EMI | 4.30 | 1.646 | 7.654 | .006 |

| EMI | 4.78 | 1.704 | |||

| Total | 4.52 | 1.689 | |||

| L18_I attend this class regularly. CLASS_ATTENDANCE (73) | Non-EMI | 5.80 | 1.376 | .209 | .648 |

| EMI | 5.86 | 1.323 | |||

| Total | 5.83 | 1.350 | |||

| L19_Even when course materials are dull and uninteresting, I manage to keep working until I finish. WORK_PERSERVERANCE (74) | Non-EMI | 5.00 | 1.385 | .229 | .633 |

| EMI | 4.93 | 1.421 | |||

| Total | 4.97 | 1.400 | |||

| L20_When studying for this course I try to determine which concepts I don’t understand well. UNDERSTANDING (76) | Non-EMI | 5.03 | 1.217 | 1.480 | .225 |

| EMI | 4.86 | 1.395 | |||

| Total | 4.95 | 1.304 | |||

| L21_I often find that I don’t spend very much time on this course because of other activities. STUDY_TIME (77) | Non-EMI | 4.09 | 1.663 | 2.792 | .096 |

| EMI | 3.79 | 1.735 | |||

| Total | 3.95 | 1.701 | |||

| L22_When I study for this class, I set goals for myself in order to direct my activities in each study period. SELF_REGULATION (78) | Non-EMI | 4.22 | 1.430 | 3.782 | .053 |

| EMI | 4.51 | 1.415 | |||

| Total | 4.36 | 1.429 | |||

| L23_If I get confused taking notes in class, I make sure I sort it out afterwards. NOTE_REVISION (79) | Non-EMI | 4.59 | 1.654 | .080 | .777 |

| EMI | 4.54 | 1.746 | |||

| Total | 4.57 | 1.695 | |||

| L24_I rarely find time to review my notes or readings before an exam. STUDY_TIME_DISPERSION (80) | Non-EMI | 4.73 | 1.732 | 2.496 | .115 |

| EMI | 5.02 | 1.699 | |||

| Total | 4.87 | 1.720 |

The variables where there are significant differences are highlighted in bold.

The variables that non-EMI students have higher significant averages when compared with non-EMI students, are L-10; study techniques (4.81 versus 4.47) and L-14; attitudes of frustration towards difficult and complex materials (4.14 versus 3.64). Another variable with significant statistical difference is L-21; time study, where non-EMI students (4.09) answer that they do not spend enough time studying because of other activities, while EMI students (3.79) spend more time studying. Perhaps this could be due to the fact that EMI students face more challenges for learning than non-EMI students and consequently tend to spend more time studying (Hernandez-Nanclares & Jimenez-Munoz, 2015). It is remarkable that one of the lowest values is the time that students spend studying. In the other seventeen items there are no significant differences between EMI and non-EMI student learning strategies.

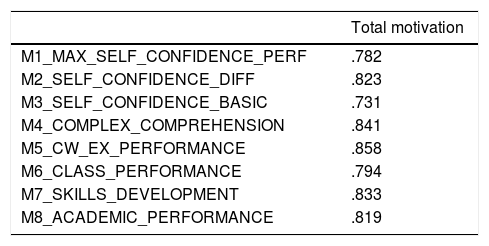

In addition, we have completed a factor analysis for the eight motivation questions in order to analyse which variables influence students’ total motivation (RQ3). Considering the high correlations among the eight motivation questions, they have been integrated in a single new factor called “TOTAL MOTIVATION” (see Table 5).

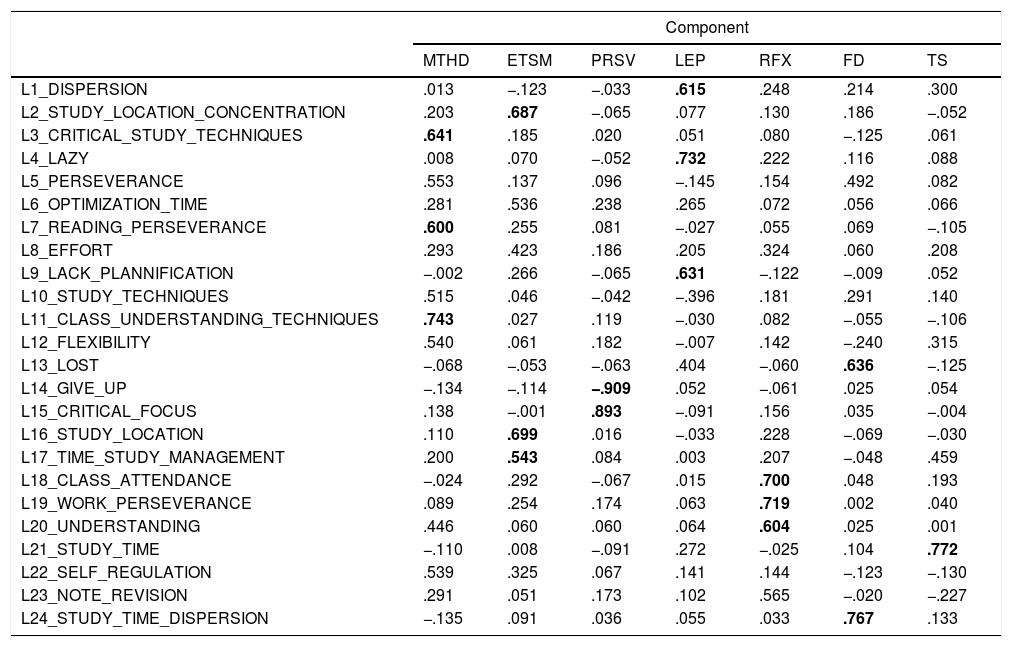

In the same way, by principal component analysis, the twenty-four questions regarding learning strategies have been integrated into seven factors. The rotated matrix was calculated after eight iterations (see Table 6).

Principal component analysis for students’ learning strategies.

| Component | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTHD | ETSM | PRSV | LEP | RFX | FD | TS | |

| L1_DISPERSION | .013 | −.123 | −.033 | .615 | .248 | .214 | .300 |

| L2_STUDY_LOCATION_CONCENTRATION | .203 | .687 | −.065 | .077 | .130 | .186 | −.052 |

| L3_CRITICAL_STUDY_TECHNIQUES | .641 | .185 | .020 | .051 | .080 | −.125 | .061 |

| L4_LAZY | .008 | .070 | −.052 | .732 | .222 | .116 | .088 |

| L5_PERSEVERANCE | .553 | .137 | .096 | −.145 | .154 | .492 | .082 |

| L6_OPTIMIZATION_TIME | .281 | .536 | .238 | .265 | .072 | .056 | .066 |

| L7_READING_PERSEVERANCE | .600 | .255 | .081 | −.027 | .055 | .069 | −.105 |

| L8_EFFORT | .293 | .423 | .186 | .205 | .324 | .060 | .208 |

| L9_LACK_PLANNIFICATION | −.002 | .266 | −.065 | .631 | −.122 | −.009 | .052 |

| L10_STUDY_TECHNIQUES | .515 | .046 | −.042 | −.396 | .181 | .291 | .140 |

| L11_CLASS_UNDERSTANDING_TECHNIQUES | .743 | .027 | .119 | −.030 | .082 | −.055 | −.106 |

| L12_FLEXIBILITY | .540 | .061 | .182 | −.007 | .142 | −.240 | .315 |

| L13_LOST | −.068 | −.053 | −.063 | .404 | −.060 | .636 | −.125 |

| L14_GIVE_UP | −.134 | −.114 | −.909 | .052 | −.061 | .025 | .054 |

| L15_CRITICAL_FOCUS | .138 | −.001 | .893 | −.091 | .156 | .035 | −.004 |

| L16_STUDY_LOCATION | .110 | .699 | .016 | −.033 | .228 | −.069 | −.030 |

| L17_TIME_STUDY_MANAGEMENT | .200 | .543 | .084 | .003 | .207 | −.048 | .459 |

| L18_CLASS_ATTENDANCE | −.024 | .292 | −.067 | .015 | .700 | .048 | .193 |

| L19_WORK_PERSEVERANCE | .089 | .254 | .174 | .063 | .719 | .002 | .040 |

| L20_UNDERSTANDING | .446 | .060 | .060 | .064 | .604 | .025 | .001 |

| L21_STUDY_TIME | −.110 | .008 | −.091 | .272 | −.025 | .104 | .772 |

| L22_SELF_REGULATION | .539 | .325 | .067 | .141 | .144 | −.123 | −.130 |

| L23_NOTE_REVISION | .291 | .051 | .173 | .102 | .565 | −.020 | −.227 |

| L24_STUDY_TIME_DISPERSION | −.135 | .091 | .036 | .055 | .033 | .767 | .133 |

Extraction method: principal component analysis. Rotation method: varimax with Kaiser normalisation.

MTDH: methodology; ETSM: external time-study management PRSV: perseverance LEP: lack of effort and planning skills; RFX: reflectiveness; FD: focus difficulty; TS time study

In bold, the main components of each learning strategy.

The seven learning strategies factors were denominated methodology (MTHD); external time-study management (out of class) (ETSM); perseverance (PRSV); lack of effort and planning skills (LEP); reflectiveness (RFX); focus difficulty (FD) and time-study (TS). The first set of variables is defined as “methodology (MTHD)”. For the students’ critical class techniques, class understanding techniques and reading perseverance were the most significant variables. The second group is classified as “external time-study management (ETSM)” where the most representative elements were the students’ finding a location to concentrate and study. The third has been defined as “perseverance (PRSV)” where the significant variables were class attendance, work perseverance and subject understanding. The fourth cluster is labelled “lack of effort and planning skills (LEP)”. Here, the most important variables were students’ inattention, laziness and lack of planning. The fifth set is denominated “reflectiveness (RFX)”, as the aspects covered here are their attitude towards frustration and their critical focus. The sixth has been defined as “focusing difficulty (FD)”, as the significant variables were that the student perceives he/she cannot follow the subject and study dispersion. Finally, the seventh cluster is defined as “time-study (TS)” where the variables scoring the highest were study time and study time management.

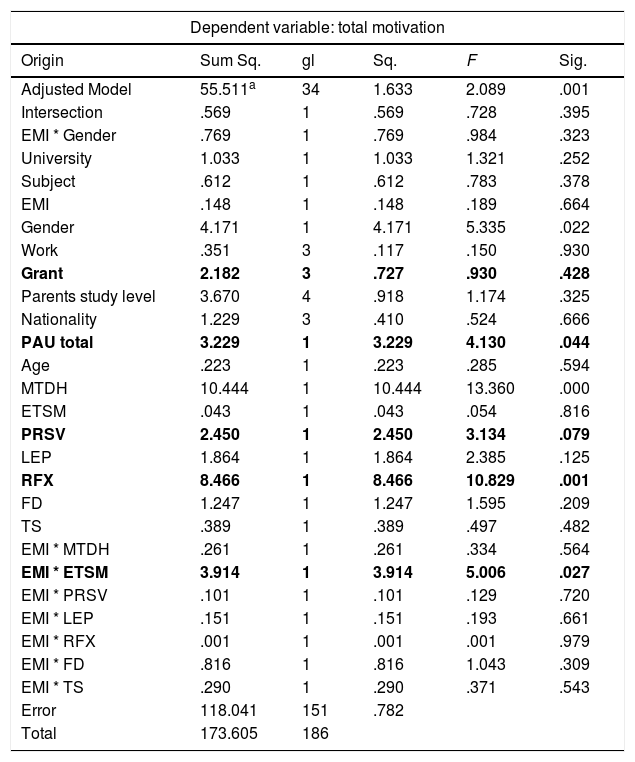

Once the factorising was complete, a regression analysis was executed to identify which factors could condition total motivation in students of Accounting subjects (RQ 3). Variables such as gender and the university access grade together with the following learning strategies factors: methodology, perseverance and reflectiveness affect “TOTAL MOTIVATION”. Additionally, iterations have been done with all the variables and the factors with EMI. Only the iteration between the external time-study management (ETSM) with EMI affects the total motivation as well. All parameters of the function lie below the significance level of 10% (see Table 7).

Regression analysis.

| Dependent variable: total motivation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Sum Sq. | gl | Sq. | F | Sig. |

| Adjusted Model | 55.511a | 34 | 1.633 | 2.089 | .001 |

| Intersection | .569 | 1 | .569 | .728 | .395 |

| EMI * Gender | .769 | 1 | .769 | .984 | .323 |

| University | 1.033 | 1 | 1.033 | 1.321 | .252 |

| Subject | .612 | 1 | .612 | .783 | .378 |

| EMI | .148 | 1 | .148 | .189 | .664 |

| Gender | 4.171 | 1 | 4.171 | 5.335 | .022 |

| Work | .351 | 3 | .117 | .150 | .930 |

| Grant | 2.182 | 3 | .727 | .930 | .428 |

| Parents study level | 3.670 | 4 | .918 | 1.174 | .325 |

| Nationality | 1.229 | 3 | .410 | .524 | .666 |

| PAU total | 3.229 | 1 | 3.229 | 4.130 | .044 |

| Age | .223 | 1 | .223 | .285 | .594 |

| MTDH | 10.444 | 1 | 10.444 | 13.360 | .000 |

| ETSM | .043 | 1 | .043 | .054 | .816 |

| PRSV | 2.450 | 1 | 2.450 | 3.134 | .079 |

| LEP | 1.864 | 1 | 1.864 | 2.385 | .125 |

| RFX | 8.466 | 1 | 8.466 | 10.829 | .001 |

| FD | 1.247 | 1 | 1.247 | 1.595 | .209 |

| TS | .389 | 1 | .389 | .497 | .482 |

| EMI * MTDH | .261 | 1 | .261 | .334 | .564 |

| EMI * ETSM | 3.914 | 1 | 3.914 | 5.006 | .027 |

| EMI * PRSV | .101 | 1 | .101 | .129 | .720 |

| EMI * LEP | .151 | 1 | .151 | .193 | .661 |

| EMI * RFX | .001 | 1 | .001 | .001 | .979 |

| EMI * FD | .816 | 1 | .816 | 1.043 | .309 |

| EMI * TS | .290 | 1 | .290 | .371 | .543 |

| Error | 118.041 | 151 | .782 | ||

| Total | 173.605 | 186 | |||

Dependent variable: total motivation.

Independent variables: gender; age; nationality; work; PAU total=university access grade (homogenised for all students out of 14); grant; parents’ level of study (MTDH: methodology; ETSM: external time-study management PRSV: perseverance LEP: lack of effort and planning skills; RFX: reflectiveness; FD: focus difficulty; TS; time study.

The significant variables determining over the dependent variable are highlighted in bold.

The first result obtained is that total motivation of students is related to variables such as gender, university access grade, methodology, reflectiveness, perseverance and when EMI interacts with external time-study management. Out of the general descriptive data of the participants, only gender and university access grade influence total motivation. As first-year students, females are more motivated than males. Previous grades also affect motivation because high grades influence self-confidence, which in turn influences motivation. These two results are in line with Honigsfeld and Dunn (2003). Moreover, students who have previously studied in English have become more used to facing challenges and finding meaning, with the subsequent rewards of higher university access grades. According to Hernandez-Nanclaes and Jimenez-Muñoz (2015), EMI students need sufficient linguistic skills in order to sustain the cognitive processes necessary for their learning in English. Moving on to the learning strategies that influence total motivation, there are three: methodology, perseverance and reflectiveness. This means that more motivated students have more mature learning strategies such as having a better learning methodology, being more perseverant and more reflective. This could be because EMI students have more difficulties when they learn contents in a different language than their mother tongue (Airey, 2009; Airey & Linder, 2006; Hellekjaer, 2010). Indeed, Buck (2001) points out that EMI students need high knowledge process levels in order to understand the main ideas in other language. Additionally, our study reveals that external time-study management when interacted with EMI students also affects total motivation for learning. This means that EMI students have better time-study management, which positively affects their motivation to study. In general, our results corroborate the conclusions of Evans and Morrison (2011) in another context that highlights that EMI students overcome learning problems through a combination of strong motivation, hard work and effective learning strategies.

ConclusionsThe objective of this paper is to analyse if there are differences in motivation and learning strategies between EMI and non-EMI students studying Accounting subjects. In addition, we have also analysed the factors that could influence students’ total motivation. We use a sample of 368 Business Administration students from three different Madrilenian universities that complete a short version of the MSLQ questionnaire. We consider our sample to be representative and balanced regarding the number of EMI and non-EMI students, gender, type of university, and accounting subjects chosen. Moreover, the collaboration and sharing between three different universities enrich the results of this study.

Our research finds that EMI students have higher motivation and use better learning strategies than their counterparties. Regarding motivation, two items show significant differences; EMI students are more self-confident in correctly understanding basic and complex concepts. In general, EMI students have more confidence and perform better than non-EMI students, believing they could achieve a high mark in Accounting coursework, exams and even in performing better in class, although there are no total significant differences. In relation to the learning strategies scales, EMI students have better learning strategies due to metacognitive self-regulation, time study management and effort regulation show significant differences. EMI students also score higher in effort, use better study time-management techniques, and are more perseverant and better organised than their counterparties. In other words, EMI students have chosen to study in a foreign language, they are conscious of having to make an extra effort, set organisation goals more effectively and perceive they self-regulate their study time better than non-EMI students. It is interesting to highlight that EMI students do not give up easily, scoring lower in the tendency towards frustration. The research also shows that non-EMI students rank higher in superficial study techniques and dedicate less study time than EMI students. From these findings, we can conclude that EMI students are more motivated, work harder, regulate their study time better, and are more persistent.

Analyzing the factors that could condition their total motivation five variables are shown relevant: gender, university access grade, methodology, perseverance and reflectiveness. Additionally, iterations have been done with all variables and factors. Only the iteration between the external time study management (ETSM) with EMI affects the total motivation as well. Female students are more motivated and previous grades also affect motivation. Methodology, perseverance and reflectiveness as learning strategies also improve students’ motivation. Concretely, critical thinking, class understanding techniques, students’ focus ability, and their level of frustration, work perseverance and class attendance are all learnings strategies that increase their motivation. It shows that more motivated students have more mature learning strategies. It would be interesting to carry out further research on motivation and learning strategies in relation to other variables such as English proficiency level, continuous assessment, exam performance and type of subject.

Another important outcome is that these findings serve as a guide for lecturers to help students (without distinguishing between EMI and non-EMI) improve their study methodology, perseverance and reflectiveness. The latter should be encouraged by lecturers understanding that motivation is dynamic not static and that learning strategies can be developed. Being aware of the students’ learning strategies (such as self-regulation and study-time management), instructors can adapt their teaching procedures in order to help students achieving deep learning.

This paper has its limitations. This study has been carried out just on Business Administration Degree in some Madrilenian universities. We also consider that the questionnaire should include the students’ level of English and general academic performance to analyses the implications of the new variables of motivation and learning strategies. Further research could also address whether their motivation to study in English goes beyond mere study grades, and includes future objectives such as an Erasmus grant or finding a better job in the future. Also, we should review the reverse-coded questions given that the students returned unusual scores and it could be they did not fully understand the question. Finally, we hope that our analysis serves as impetus for further research involving other universities and institutions, thereby providing a greater number of students and a wider range of subjects. Such repeated analysis over time would help us to better understand our students and know what factors help motivate them to learn more effectively.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

This research was partially supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness under the RD project Inte-R-LICA (The Internationalisation of Higher Education in Bilingual Degrees) for the period 2014–2016 (Ref. FFI2013-41235-R). The authors thank to the participants of the XVII Encuentro ASEPUC held in Bilbao (14–17th June 2016) their comments and suggestions, particularly our discussant Dra. Zorio. The authors also thank Ms Alejandra Encina for the database design.

All these data will be statistically used in an anonymous way

ID number (DNI or passport):

Please, choose only one answer for the following questions.

- 1.

Please, circle your gender.

- 1.

Male

- 2.

Female

- 2.

In which year were you born?:

- 3.

Which nationality do you have?

- 1.

Spanish

- 2.

Non-Spanish

- 3.

Both

- 4.

Weekly time spent in paid employment

- 1.

I do not work

- 2.

Less than 10 hours a week

- 3.

Between 10 and 20 hours a week

- 4.

More than 20 hours a week

- 5.

What was your numerical university access grade?:

- 6.

Do you have a grant?

- 1.

No, I do not have a grant

- 2.

Yes, I have an Academic Excellence Grant

- 3.

Yes, I have a State Grant

- 7.

Your parents’ level of studies

- 1.

Primary

- 2.

Secondary

- 3.

University degree

- 4.

Master's degree

- 5.

Ph.D. degree

The following questions ask about your motivation for and attitudes about this class. Remember there are no right or wrong answers; just answer as accurately as possible. Use the scale below to answer the questions. If you think the statement is very true of you, mark 7; if a statement is not at all true of you, mark 1. If the statement is more or less true of you, find the number between 1 and 7 that best describes you.

| Motivation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I believe I will receive an excellent grade in this class. | |||||||

| 2. I’m certain I can understand the most difficult material presented in the readings for this course. | |||||||

| 3. I’m confident I can learn the basic concepts taught in this course. | |||||||

| 4. I’m confident I can understand the most complex material presented by the instructor in this course. | |||||||

| 5. I’m confident I can do an excellent job on the assignments and tests in this course. | |||||||

| 6. I expect to do well in this class. | |||||||

| 7. I’m certain I can master the skills being taught in this class. | |||||||

| 8. Considering the difficulty of this course, the teacher, and my skills, I think I will do well in this class. | |||||||

| Learning strategies | |||||||

| 1. During class time I often miss important points because I’m thinking of other things. | |||||||

| 2. I usually study in a place where I can concentrate on my course work. | |||||||

| 3. When reading for this course, I make up questions to help focus my reading. | |||||||

| 4. I often feel so lazy or bored when I study for this class that I quit before I finish what I planned to do. | |||||||

| 5. When I become confused about something I’m reading for this class, I go back and try to figure it out. | |||||||

| 6. I make good use of my study time for this course. | |||||||

| 7. If course readings are difficult to understand, I change the way I read the material. | |||||||

| 8. I work hard to do well in this class even if I don’t like what we are doing. | |||||||

| 9. I find it hard to stick to a study schedule. | |||||||

| 10. Before I study new course material thoroughly, I often skim it to see how it is organised. | |||||||

| 11. I ask myself questions to make sure I understand the material I have been studying in this class. | |||||||

| 12. I try to change the way I study in order to fit the course requirements and the instructor's teaching style. | |||||||

| 13. I often find that I have been reading for this class but don’t know what it was all about. | |||||||

| 14. When course work is difficult, I either give up or only study the easy parts. | |||||||

| 15. I try to think through a topic and decide what I am supposed to learn from it rather than just reading it over when studying for this course. | |||||||

| 16. I have a regular place set aside for studying. | |||||||

| 17. I make sure that I keep up with the weekly readings and assignments for this course. | |||||||

| 18. I attend this class regularly. | |||||||

| 19. Even when course materials are dull and uninteresting, I manage to keep working until I finish. | |||||||

| 20. When studying for this course I try to determine which concepts I don’t understand well. | |||||||

| 21. I often find that I don’t spend very much time on this course because of other activities. | |||||||

| 22. When I study for this class, I set goals for myself in order to better manage my activities in each study period. | |||||||

| 23. If I get confused taking notes in class, I make sure I sort it out afterwards. | |||||||

| 24. I rarely find time to review my notes or readings before an exam. | |||||||