Realism posits that strong states use compulsory power to influence the behavior of weaker ones. If true, then U.S. policy toward Mexico on a key national security issue such as drugs should illustrate that claim and policy outcomes should reflect U.S. preferences. Yet, in exploring a series of bilateral case studies, this article suggests that unilateral U.S. government initiatives do not achieve their specified goals. Rather, we argue that Mexico effectively employs a series of “strangulation strategies.” These derail U.S. initiatives and -under specific conditions- result in institutional agreements that proscribe certain forms of behavior and reduce future U.S. autonomy.

El realismo sostiene que los Estados fuertes utilizan su poder de coacción para influir en el comportamiento de los débiles. Si esto es verdad, entonces la política estadunidense sobre México en un tema clave de la seguridad nacional como es el de las drogas debería ilustrar que las políticas públicas y las reclamaciones en la materia tendrían que reflejar las preferencias de Estados Unidos. No obstante, al explorar un conjunto de estudios de caso bilaterales este artículo sugiere que las iniciativas unilaterales del gobierno estadunidense no consiguen alcanzar sus metas tal como fueron formuladas. Por el contrario, argumentamos que México emplea con mucha eficacia una serie de “estrategias de estrangulación”. Estas hacen descarrilar a las iniciativas de Estados Unidos y -bajo ciertas condiciones- terminan en acuerdos institucionales que prohiben algunas formas de conducta y podrían reducir la autonomía estadunidense en el futuro.

On February 2, 2012, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder appeared before a congressional committee to give testimony on the failed U.S. operation “Fast and Furious.” It was the sixth time in a year he had given testimony on the program, an ill-fated attempt to trace unlawfully purchased weapons from the U.S. into Mexico. He denied authorizing the program or covering up later investigations. He called it “unacceptable” and “stupid” (Huffington Post, 2012).

Fast and Furious was a program through which the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (atf) allowed an estimated 1 730 weapons to “walk” so they could be traced to cartels and other criminals (U.S. Congress, 2011: 5). Straw purchasers for drug cartels bought the weapons, and many were smuggled into Mexico. In fact, a number of murders were carried out with the weapons before they were recovered by the Mexican authorities (including a 2010 murder of a U.S. Border Patrol agent, Brian Terry), while others are still missing. Both Mexican leaders and frontline atf personnel criticized the operation as irresponsible and misguided, and U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder accepted that the operation was flawed in concept and execution.

Curiously, at the same time that atf field agents sanctioned this initiative, Mexico and the U.S. achieved unprecedented levels of cooperation as a result of the Méri-da Initiative. Mérida was a three-year plan designed to aid Mexico’s fight against drug trafficking organizations (dtos). Little had changed from the late 1990s, when Benjamin F. Nelson appeared before the U.S. Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control and listed a litany of failures by the Mexican government: the failure to institute programs, the failure to address issues of corruption, the failure to implement prescribed policies (U.S. Senate, 1999: 5).1 Yet the lack of progress had little bearing on the White House’s decision to recertify Mexico as “cooperating fully” with the United States.

A pattern has emerged in U.S.-Mexico relations on drug-related organized crime, beginning with U.S. frustration over lack of results, or poor performance by Mexican agencies. Of course, U.S. frustration is mirrored across the border, from the moment when President Nixon raised the stakes by employing military metaphors in describing the “war on drugs.” Mexico distrusts the United States because of its inability or unwillingness to reduce its huge consumer demand and its ineffectiveness in stopping the export of arms to Mexican cartels. The stakes rose considerably for Mexico when the Caribbean route was closed down and cartels sought alternative land routes into the U.S., especially for cocaine. Mexico has also been frustrated by failures to deliver funding for the Mérida Initiative, U.S. interference in law enforcement operations, and limited technological transfers under Mérida. Likewise, some apparent successes in generating closer cooperation in drug policy have themselves produced various failures. Calderón’s military war on the drug cartels, for example, was supported by Washington, but has produced unprecedented levels of violence in Mexico and generated greater insecurity along the border.

We acknowledge that the U.S.-Mexico relationship over the issue of drug trafficking is complex and controversial. We do not attempt to address the full panoply of bilateral issues and histories, but rather identify a pattern in the relationship: on the U.S. side, frustration leads to a unilateral U.S. policy that backfires, either because it fails spectacularly (as in Fast and Furious) or because it is resisted angrily by Mexico (as in certification). The U.S. then subsequently responds by agreeing to participate in jointly-operated cooperative initiatives, which are far more effective for achieving its goals.

What explains this puzzle, in which Mexico is repeatedly adjudged ineffective or disingenuous in the fight against drugs, yet is rewarded with cooperation? We contend that the United States has become a prisoner of a sovereignty dynamic of its own making in which unilateral action, whether successful or not, leads to an abrogation of the norm of bilateral cooperation, and an ensuing process of regulation that gradually constrains its behavior. Paradoxically, the unilateral assertion of sovereign prerogatives by the United States generates increased institutionalization -constraining future U.S. American behavior. Unilateralism thus initiates a cycle in which Mexico reacts defensively on the grounds that its sovereignty has been violated and seeks to limit U.S. room for maneuver. New agreements are reached and regulations signed (what we label “strangulation strategies”), and another policy area is created in which the United States has less latitude to act autonomously. U.S. American policy moves from “a messianic phase in which it claim [s] self-righteous leadership to a trough of self-doubt” and cooperation (Reich, 2010: 8).

In the following sections, we explore how the distinctions between forms of sovereignty outlined by Stephen Krasner in Sovereignty: Organized Hypocrisy (1999) help frame an understanding of the cycle of unilateralism and cooperation. We then set out the logic of this approach in the context of the drug wars, and finally examine the empirical results of U.S.-Mexico interaction. Ultimately, our aim is to explain a major paradox in U.S. policy, to identify the types of policies that the United States might be able to implement, and specify the conditions under which such policies offer the prospect of success.

The Logic of Sovereignty and CooperationMuch of the debate about drug policy, as we have characterized it, concerns conceptions of the definition of sovereignty, the exercise of power, and the institutional context in which power is exercised. Elsewhere, we address in depth the theoretical weaknesses of realism in explaining this relationship (Reich and Aspinwall, 2013). In brief, one perspective believes that weak states are only able to prevail against stronger states if they have access to counterbalancing alliances or something highly valued by the larger state that they can use as leverage (Wohlforth, 1999; Baker Fox, 1959; Roth-stein, 1982:159-160). Mexico, however, is not a member of any global or regional organization that can dilute U.S. interference, nor can it effectively align with regional or global partners in a way that counterbalances U.S. America’s material advantages (Sanchez, 2003: 58; Vital, 1967). Others have claimed that weak states may prevail when favored by geography or greater resolve (Bjol, 1968). But drugs are a key security issue for the U.S., with easy access to its neighbor from where the problem “originates.”

Of central importance to us here is a key realist concept, that of sovereignty. In his book on that subject, Stephen Krasner discusses alternative uses of the term: The term sovereignty has been used in four different ways -international legal sovereignty, Westphalian sovereignty, domestic sovereignty, and interdependence sovereignty. International legal sovereignty refers to the practices associated with mutual recognition, usually between territorial entities that have formal juridical independence. Westphalian sovereignty refers to political organization based on the exclusion of external actors from authority structures within a given territory. Domestic sovereignty refers to the formal organization of political authority within the state and the ability of public authorities to exercise effective control within the orders of their own polity. Finally, interdependence sovereignty refers to the ability of public authorities to regulate the flow of information, ideas, goods, people, pollutants, or capital across the borders of their state. (1999: 4)

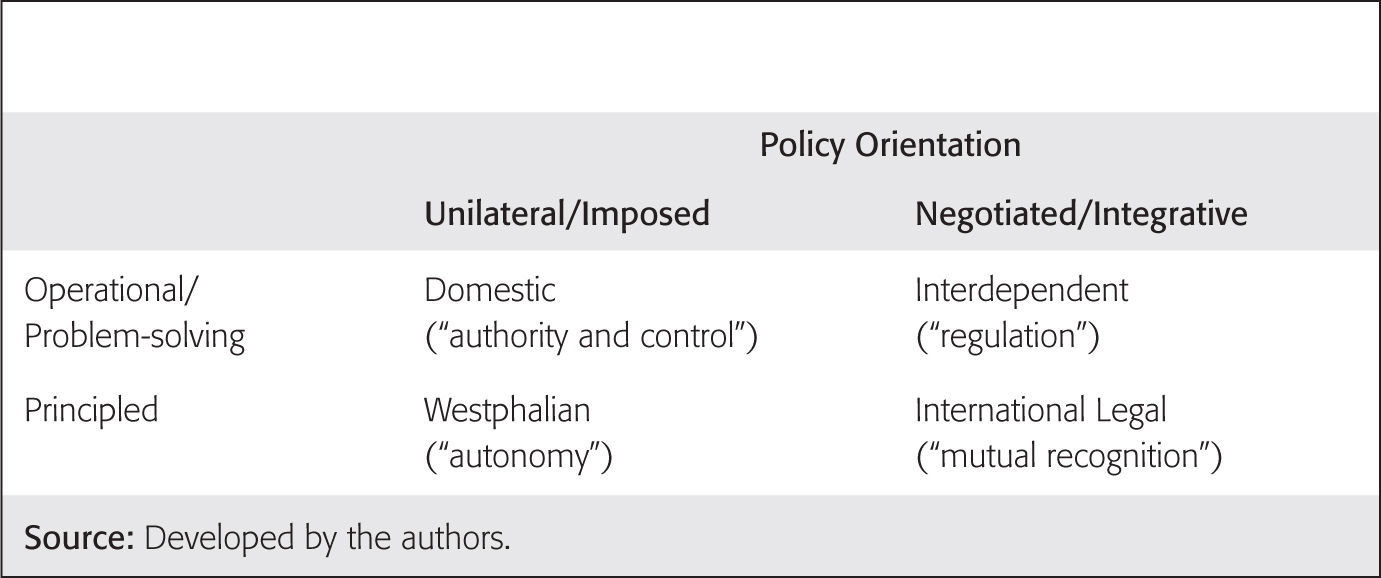

We adopt Krasner’s variety of definitions for two reasons. First, we aim to improve our understanding of the relationship between the exercise of power and the way in which that influences authority, legitimacy, and control. Utilizing these concepts in dynamic rather than static terms may make the definitional distinctions more operationally useful. Second, we seek to apply these concepts to the issue of U.S.Mexican drug policies in the hope that they provide a heuristic framework that may help address a current and ongoing economic and security problem for the United States. We depict these varied conceptions of sovereignty in Figure 1.

In this figure, we suggest that sovereignty can be disaggregated along two dimensions. Krasner’s ideal-types can be distinguished between its operational and its principled dimensions. Sovereignty has an instrumental, pragmatic purpose, because it enables states to establish and exert authority and control, to regulate and establish norms and rules. But states also invoke sovereignty as a principle, because that is how they establish themselves as entities. They seek recognition and recognize others by invoking or employing the concept of sovereignty.

Our second distinction is between a unilateral (or imposed) and a negotiated (cooperative or integrative) dimension. In this regard, states may act without the cooperation or recognition of other states in solving problems or establishing the principle of autonomous existence. Equally, they may work bilaterally or multilaterally when solving problems or establishing their sovereign right to exist (through the mechanism of mutual recognition). Krasner’s Westphalian sovereignty and domestic sovereignty both imply unilateral decision-making processes. In contrast, interdependent and international legal forms of sovereignty imply a negotiated exercise of power, requiring the cooperation of other states.

Applying This Framework Dynamically To Mexican-U.S. Drug PolicyHow do these distinctions operate in practice? We assume that both the U.S. and Mexico operate rationally, that their executives are constrained by domestic actors, but that they have transient preferences -that is, preferences that are more or less consistent from administration to administration. For the U.S., its primary preference is to stem the flow of drugs. Although the problems associated with drug use in the U.S. (crime, violence, public health, etc.) could conceivably be mitigated by bet ter treatment programs or stronger U.S. enforcement, the political costs are believed to be lower when the problem is externalized (to Mexico and other source countries). Mexico also wants to stem the flow of drugs. But maintaining domestic social order and protecting its sovereignty while retaining the benefits of the close relationship with the U.S. (through trade) are higher priorities.

Each executive operates under domestic constraints. The U.S. president is constrained by Congress (which consistently focuses on results in a division between hard-line “hawks” who favor unilateral security responses at the border, and “doves” who favor cooperative strategies), and by public opinion (on the potential contradictions between domestic and international policies see Putnam, 1988). Mexico’s executive is also constrained by its Congress (which is divided between leftist intellectuals for whom autonomy is sacrosanct and a newer cosmopolitan cohort who favor cooperation), and by nationalist elites who avowedly oppose what they regard as opportunistic U.S. interference (Carrasco Araizaga, 2011; Esquivel, 2011). Public opinion generally favors U.S. involvement in the war on drugs and believes the current Mexican government has failed in that regard (González et al., 2011).

The logic of action from the U.S. perspective is an operational, results-oriented one of problem-solving to placate public opinion through externalized action. Unilateral solutions are preferred because Mexico is not fully trusted, though, in principle, the U.S. recognizes the advantage of a cooperative approach (Mares, 1992). The logic of action from the Mexican perspective is to resist U.S. unilateralism while ceding enough in terms of results -or the perception of sufficient results- to retain the benefits of its relationship with the U.S. Mexico’s strategy involves reducing the United States’ room for autonomous action through a process of institutionalization that we label “strangulation strategies.”

There is thus an identifiable, regularized, and dynamic pattern to their interaction that reflects Krasner’s varied ideal types. As U.S. American frustration with ineffective results grows, so does the temptation to act unilaterally. A unilateral policy thrust (mainly following the domestic variant of sovereignty) designed to achieve specified policy goals has an unintended effect: a growing tendency by Mexico to focus on issues of sovereignty rather than drug eradication (Chabat, 1993; Reuter and Ronfeldt, 1992). Mexico responds with a Westphalian sovereignty strategy designed to reassert its autonomy. The U.S., focusing on reducing the flow of drugs, has little option but to accede. What follows is the introduction of regulation primarily intended by Mexico to curtail future unilateral U.S. behavior. These “strangulation strategies” narrow the policy areas available for the autonomous exercise of U.S. power. Clearly, it is not Washington’s intent to adopt unilateral policies that will result in narrowing its subsequent policy options, but such is the unintended feedback effects of these perverse strategies (on this process generally, see Pierson, 1993). Strangulation combined with recognition that the problem of threat interdependence cannot be solved unilaterally leads to a new logic. Once the U.S. recognizes that the problem is one of interdependence rather than a matter of asserting domestic sovereignty, it formulates a bilateral strategy. From the two logics -of problem solving and resistance- the U.S. and Mexico together arrive at a logic of cooperation.

Thus, the evident paradox -one whereby U.S. leaders can simultaneously speak of the success of certain operations and failure elsewhere- is explained by the dynamic that ensues in the aftermath of U.S. unilateralism, one in which Mexicans protest and U.S. Americans agree to institute new regulations that primarily address the issue of U.S. American unilateralism rather than drug interdiction, and so ignores the underlying policy issue. Unilateral U.S. policy carries the seeds of its own future policy limitations and the inevitable prospect of reduced autonomy. The sovereignty cycle is complete.

Yet, the cycle we have identified, while most common, only occurs when the U.S. initiates a unilateral policy. There is also evidence of an alternative pattern than ensues when the process is initiated on a bilateral basis, attempting to address jointly identified problems, founded on principles derived from international legal sovereignty and employing regulations derived from interdependent sovereignty. The empirical evidence suggests that only this negotiated problem-solving approach generates more positive outcomes in the fight against drugs, recognizing that success is a relative concept and that the implementation of coordinated initiatives is the nearest we can offer as a measure of success in an endless war.

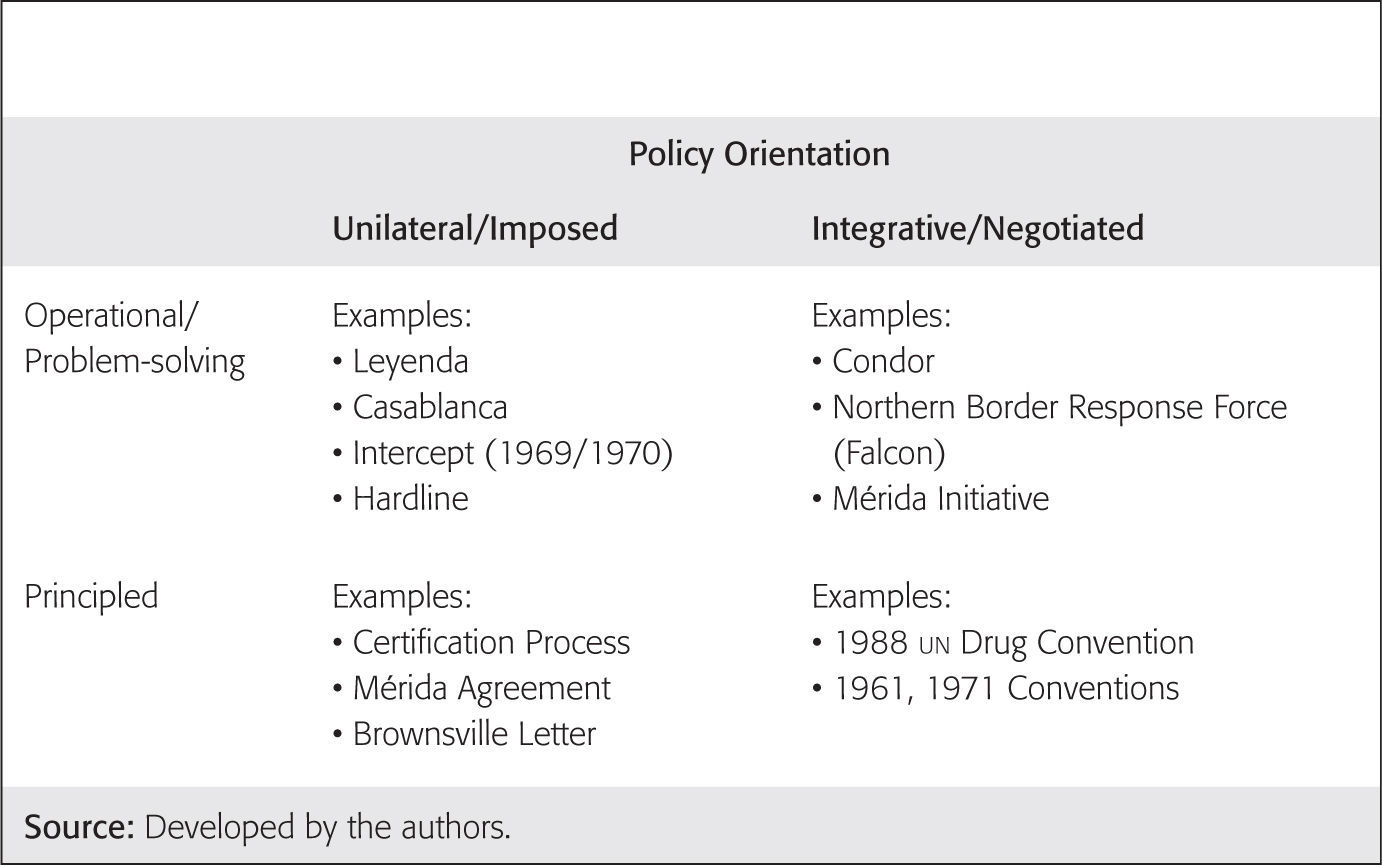

Conditions and Cases for Drug EradicationWe have outlined a common process and an alternative dynamic, But, how can this framework be employed empirically to distinguish between various operations and their corresponding programs? Do the four categories work in terms of identifying patterns of interaction and variation in results? Figure 2 extends our analytical framework to distinguish a dozen U.S.-led drug interdiction initiatives relevant to drug interdiction over the last five decades. Some were unilateral, others negotiated. Equally, some were designed to solve problems, others to establish principles. Using these cases, we demonstrate that the framework offers valid distinctions between cases and is useful in describing their dynamics and consequences.

Basing policy on both the principle of international sovereignty and also operational interdependent sovereignty is more likely to bring favorable results. The reason is that effective cooperation requires that certain conditions be in place that overcome transaction costs and lead to efficiency gains. We elaborate the conditions below. When the conditions are met, cooperation is more likely to be effective, as reflected in the cases listed in the top right hand box.

The first condition is the existence of mutual interest in the administration of any program. This is not the same thing, of course, as having the same interest. But any program where Mexican authorities see no clear and significant reason for action is doomed to failure. Second, communication and coordination are essential. Programs must be coordinated not only across national sovereign jurisdictions but also within national administrative jurisdictions to avoid contradictory initiatives and to ensure that trust is not subverted. With so many federal agencies involved in drug interdiction in Mexico, it is easy -if not inevitable- for individual agencies to pursue policies that contradict the efforts of other agencies, undermining cross-border efforts at cooperation and adopting unilateral strategies to protect secrecy.

Third, institutionalization (that is, regulanzation of agreements, contacts, and communication between agencies and officials such as the High Level Consultative Group) is important because it commits bureaucratic personnel to regular interaction with counterparts across the border, provides continuity, and overcomes shifts in political priorities (Aspinwall, 2009). Committing senior personnel to consultation increases each side’s stake and locks in stakeholders from both countries. Finally, capacity-building facilitates cooperation because it increases and “tunes” skill levels. This can occur through the provision of resources and new technologies, such as equipment. It also occurs through training exercises, secondments, and placements, where personnel from one side are implanted in the other (Aspinwall 2013). The application of new technologies and skills can generate mutual interest, and thus may help overcome prior coordination problems.

If these four conditions are met, a virtuous circle is created by expanding the area of mutual interest, engendering greater trust. This leads to higher levels of legitimacy on both sides and can strengthen executives against domestic veto players. These conditions, although rare, are impossible to meet in the context of unilateral approaches. The cases that follow systematically consider these conditions in the context of different policy initiatives and examine the regulations that they generated. The requirements of a single article preclude us illustrating each case outlined in Figure 2. We therefore confine ourselves to examining one case in each box, leaving the remainder for a future, more detailed study.

Four Illustrative CasesUnilateralism-Operational: The Case of Operation CasablancaThe basic dynamic of U.S. unilateral operations and the Mexican response can be seen in three of the most prominent unilateral actions taken over the past several decades: Operation Intercept (1969), Operation Leyenda (1986,1990), and Operation Casablanca (1998). We use the most recent of these, the notorious Operation Casablanca, to illustrate this dynamic.

On May 16,1998,12 Mexican bankers were lured to Las Vegas at the invitation of “criminal associates,” for whom they had been laundering drug money but who were, in fact, undercover drug agents. The bankers were soon arrested, the culmination of a three-year undercover effort by the Clinton administration. Operation Casablanca, as it became known, led to the arrest of 160 people from six countries and from more than a dozen banks in Mexico and Venezuela, including the criminal indictment of three of Mexico’s largest banks -Bancomer, Serfin, and Confia- and 22 Mexican bank officials (Padgett, 1998; Carreno and Ferreyra, 1998). Customs agents also seized US$150 million in assets from Columbia’s Call cartel and Mexico’s Juarez cartel.

The operation caused considerable embarrassment to the Zedillo administration, not only because it revealed the depth of corruption in the already scandal-ridden banking system, but also because it was undertaken without the knowledge of the Mexican government.2 The High Level Contact Group had been established between the two countries just two years earlier, as well as a Binational Drug Control Strategy (bdcs), which took effect in 1998 and supposedly “facilitated the decisionmaking and agreement processes between both governments” (Binational Commission, n.d.). When Casablanca was launched in 1995, money laundering was not a crime in Mexico, reflecting inadequate controls over the banking sector, which had only been privatized in 1991 after a decade of government control. Lack of proper safeguards had become strikingly apparent in 1995, when it was discovered that Raúl Salinas, brother of former Mexican President Carlos Salinas, had used Citibank to shift more than US$100 million into Swiss and other foreign bank accounts.

In 1996, the Mexican government began implementing more serious anti-mon-ey-laundering legislation that gave Mexico’s National Banking and Securities Commission (cnbv) much greater authority over banks. By 1998, Mexico had criminalized money laundering and begun to monitor bank behavior much more closely. Nonetheless, U.S. government estimates at the time were that more than US$15 billion in drug money was laundered annually in Mexico, a figure equal to roughly 5 percent of the gross domestic product (Padgett, 1998:15). This figure, along with the fact that a number of high-ranking Mexican government and law-enforcement officials have been found guilty of working with drug cartels, convinced U.S. authorities that the details of Casablanca should not be shared with any Mexican officials. As the sting operation unfolded, it appeared that more than US$60 million had recently been laundered and that drug money was coming from a variety of sources, possibly including Mexico’s defense minister, General Enrique Cervantes (Golden, 1999).

Thus, U.S. authorities felt it necessary to send a signal to Mexico over its lax banking regulations, and the lack of full notification was a deliberate attempt to avoid leaks and protect the agents conducting the investigation. However, the backlash in both the Zedillo administration and Mexico’s Congress was furious. The chair of the Senate commission charged with responsibility for U.S.-Mexico relations, Martha Lara, called for the arrest of the U.S. customs agents responsible if they set foot in Mexico (Zavala and Fins, 1998). The Clinton administration’s request that five Mexican bankers be extradited to the United States in the wake of the Casablanca Affair was not only refused by the Mexican government, but they also threatened to issue formal charges against the participating U.S. agents for violating Mexican sovereignty. Mexico’s Minister of Foreign Relations Rosario Green and Attorney General Jorge Madrazo formally protested the action (Garcia and Miselem, 1998). Green went further, proposing that the United States adopt a “code of behavior” that would respect the territorial sovereignty of other countries (Ruiz, 1998). President Zedillo sent a letter of protest to the State Department and telephoned Clinton suggesting that legal action would be taken (Padgett, 1998:15).

Having impinged on Mexico’s sovereignty, Washington agreed to sign a new agreement on July 2,1998, named the “Brownsville Letter.” Among other things, the Brownsville Letter called for better communications, coordination, and training in order to avoid future Casablanca-style incidents (U.S. Department of Justice, 1998: 1-3). While the two sides recognized their shared interest in combating dtos, communication and consultation on enforcement activities needed to be strengthened, and sovereignty better respected. They agreed to joint training of law enforcement officials in order to foster a better understanding of the respective legal systems and law enforcement practices. Thus, in addition to reinforcing its sovereignty, Mexico insisted on better communication and coordination. The two attorneys general, Reno and Madrazo, agreed to install a hotline between their offices and to provide advance notice of sensitive cross-border law enforcement activities (Kempster, 1998). A number of training exercises occurred in the wake of Casablanca, under the auspices of the bdcs (Avalos-Pedraza, 2001).

The letter between the two attorneys general was converted into a memorandum of understanding, the Mérida Agreement, when President Clinton visited Mexico in February 1999. The arrangements specified under Brownsville/ Mérida were intended to expire at the end of the Clinton administration. But Jeffrey Davidow, U.S. ambassador to Mexico, insisted that U.S. law enforcement agencies in the embassy continue to operate as though the agreement were in place, even after Bush took office (Davidow, 2007; U.S. Senate, 1999). As time went on, confidence grew in the Mexican authorities, and the U.S. passed information to Mexico in greater quantities, although Washington remained much concern about the corruption of Mexican officials.

However, as is evident in other cases in which U.S. unilateral action precedes a bilateral agreement, neither side was fully satisfied. Although the former U.S. director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, Barry McCaffrey, claimed in 2000 that the level of intelligence-sharing cooperation rose dramatically (pbs, 2000a), U.S. border agents conducting operations or intelligence gathering found themselves extremely frustrated by the new consultation requirements, their cumbersome character interfering with rapid responses to evolving situations on the ground. We’re constantly having to notify. When you live and work on this border, people cross back and forth; it’s like the tide coming in and the tide going out. People cross this border four and five and six times a day. And to go through formal notifications every time to track fast moving intelligence, it’ s literally impossible. It’s very, very frustrating for the agents on the border to follow those procedures. (pbs, 2000b)

For their part, the Mexicans remained highly skeptical that the new accord would increase cooperation or curtail future sovereign violations (Castillo, 1998). The following February, Clinton and Zedillo signed a more formal accord, the so-called “Méri-da Agreement.” It imposed stricter regulations on U.S. behavior that curtailed the prospect of any future “Casablancas” (pgr, 2000: 49; Embajada de México, 1999). The Casablanca episode and its aftermath showed how the increasingly porous post-nafta borders continued to reinforce both the importance of sovereignty and of trust. “The borders are disappearing. But they are not disappearing for law enforcement,” said Wilmer “Buddy” Parker, a former assistant U.S. attorney (cited in Zavala and Fins, 1998).

Unilateralism-Principled: The Failure of the Certification ProcessDespite their many differences and continued difficulties, Mexico had proven to be the U.S.’s most cooperative partner in the fight against drugs by 1985. According to Samuel I. del Villar, Mexico had signed “47 bilateral drug-related agreements with Washington; [had] the oldest, widest, and most effective eradication campaign; and [had] the largest foreign U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (dea) operation in its territory.” (1988: 191 and 206). Reuter and Ronfeldt note that, as of 1992, Mexico was the only country in Latin America that had permitted aerial spraying, which was strongly promoted by the United States (1992: 127). The Mexican government, however, apparently did not like to share information on its military drug control policies or their results, and Washington had become concerned over verification of Mexico’s anti-drug results, especially its eradication efforts. As a 1989 Congressional report stated, “Mexico remains the only country in which it is considered advisable to verify eradication efforts” (U.S. House of Representatives, 1989). Following the murder of dea agent Enrique Camarena in 1985, and the unsuccessful closing of the border with “Operation Intercept II” in February 1986, the Reagan administration began to consider alternative “supply-side” strategies that would more effectively signal the extraterritorial extension of U.S. drug laws as well as pressure source countries to respond more seriously to Washington’s dictates.

The U.S. Congress responded with the 1986 “Anti-Drug Abuse Act,” which made it illegal to produce or distribute drugs “with the intention of exporting them to U.S. territory” (U.S. Congress, 1986). The Drug Act also allowed for U.S. federal grand jury indictments of foreign nationals. More significantly the 1986 act linked future U.S. economic and military assistance, trade preferences, and support in multilateral institutions to source countries’ ability to clearly demonstrate they were “cooperating fully” with the United States in the drug war. The level of cooperation was to be determined by the White House and then approved by the U.S. Congress through a “certification process.” Legally, Congress had to certify annually that all nations that were either drug producers or major drug-transit countries that were recipients of foreign assistance were cooperating fully with the United States in the drug war, as well as making serious efforts to deal with drug-related problems in their home countries.

The emphasis on “full cooperation” as the main criterion for certification did not necessarily mean that the level of cooperation was to be determined solely by the results achieved by the source or transit country. Moreover, the president and Congress could choose to totally ignore the criterion of cooperation if certification of the country was viewed as “vital to the national interest” of the United States. The standards for certification therefore gave Washington some degree of latitude in making its judgments. But having defined drug trafficking as a national security issue, the Reagan administration was clearly prepared to press countries like Mexico into embracing U.S. strategy and tactics, while circumventing international treaties and conventions, through the certification process. Following the conditions established by the act, Reagan sent a warning shot when he withheld US$1 million in drug aid to Mexico in 1986 until he could report progress by Mexico in the Camarena murder case. The Reagan administration also pressured the Mexican government into closing down its highly corrupt Federal Security Directorate, which had had close ties to the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency.

By contrast, Mexico regarded the certification process as a violation of its national sovereignty because the act forced Mexico “to submit its police and military to the scrutiny, ‘certification/ and ‘approval’ of the president and Congress of the United States” (Del Villar, 1988: 205; see also the Mexico City newspaper Excelsior, April 15, 1988). The Mexican government did not question the right of the U.S. Congress to link certification to foreign assistance or to pass judgment on Mexico’s domestic policies, although the act also required that the U.S. representatives vote against multilateral bank loans to any decertified country. From the Mexican perspective, certification demonstrated an obvious lack of respect with regard to its commitment to the drug war, which only served to damage the bilateral relationship. Moreover, certification appeared at times to be highly arbitrary, as evident from the certification of Noriega’s Panama when both drug running and money laundering in that country were well-known facts in Washington (Hersh, 1986). The law also “legally” threatened to disrupt Mexican-U.S. trade (Del Villar, 1988: 200). Finally, the certification process was damaging because it created a forum for criticizing foreign governments and, therefore, undermined efforts toward international cooperation (Tello Peon, 1996: 137). But certification was useful from Washington’s perspective because it focused attention on foreign supply rather than domestic demand.

Even if the Mexican government did not like the certification process, it clearly spurred it to take more aggressive action. At the time that the 1986 law was passed, officials in Washington held the view that the Mexican government “would rather destroy plants than catch people. The [Mexican] Government appears unable or unwilling to arrest and/or prosecute the major narcotics traffickers that are involved in production, processing, and distribution of narcotics” (U.S. House of Representatives, 1987). However, Mexico began to make dramatic arrests and drug seizures as the annual certification process was underway in the U.S., in what became known in Washington as the “February surprise.” In 1987 and 1988, Mexico received certification just as it has every year, but only after considerable internal debate, and in both years, Congress seriously considered overriding the president’s initial approval because of its belief that the Mexican government was not sufficiently committed to fighting the drug war and because of its seeming inability to deal with domestic corruption. In 1987, a House resolution was passed that disapproved certification for Mexico, and in 1988 a Senate resolution was passed to decertify Mexico, but in both cases the resolutions failed to get adequate congressional support (Perl, 1988: 25-34; Walker, 1995).

In the 1990s, however, the Mexican government made a more concerted effort to meet U.S. Congressional concerns and arrested both major traffickers and corrupt government officials. In March 1996, on the day that the Clinton administration was to announce whether to certify Mexico, Mexican troops swept through Tijuana in an attempt to capture the Arellano Felix brothers, leaders of the Tijuana cartel. After it was announced that Mexico had received certification, the troops ceased their pursuit. In February 1997, the Mexican government announced the arrest of General Gutiérrez Rebollo on charges of drug corruption. As the director of the National Institute to Combat Drugs, he allegedly had links to drug lord Amado Carrillo. The timing of the government’s announcement could not have been more favorable in swaying Washington toward certifying Mexico for the coming year. Even so, Clinton had a difficult time justifying Mexico’s certification, and Congress forced the president to make an additional presentation in September 1997.3 The problem was due partly to the failure of the Mexican government to capture the country’s most wanted drug trafficker, Amado Carrillo, by early 1997. Moreover, Humberto García Ábrego, the brother of Gulf Cartel boss Juan Garcia Ábrego, was able to walk out of prison where he was in custody on the day that Clinton was to announce Mexico’s certification, and no local authority could provide a clear explanation of the incident. Even more remarkably, the Mexican government withheld news of Garcia Ábrego’s release until after Clinton approved the certification (Anderson and Moore, 1999).

The congressional debate on certification in early 1999 is especially noteworthy, as it appeared that the Mexican government had made very little progress during 1998 in dealing with either drugs or corruption. Statistical evidence supported this view, and even some Mexican officials were inclined to agree. Drug arrests had fallen, drug investigations were down by 19 percent from 1997, and seizures of cocaine, marijuana, and heroin had decreased from the previous year (Anderson and Farah, 1999). Drug interdiction seemed to be less effective than in 1997, even though the Mexican government was spending approximately US$770 million on its anti-drug programs and had more than 26 000 soldiers and government personnel involved in the drug war. Of course, lower statistical measurements may have also been the result of more effective law enforcement, as some Mexicans argued, which was resulting in traffickers altering their shipping routes to the Caribbean rather than overland through Mexico.

Yet there was also evidence to suggest lower statistical measures had less to do with efficiency and more to do with corruption. In September 1998, a special Mexican army anti-drug unit,4 whose leadership was trained by U.S. Special Forces and the cia, was removed from their duties at Mexico City’s airport due to their alleged involvement in illegal drug and immigration rings. Additional U.S.-trained Mexican law enforcement officers were charged in 1998 with using a government plane to ship cocaine (Farah and Moore, 1998). Also disturbing was the fact that no major Mexican drug dealer had ever been extradited to the United States up to that time, new money laundering laws had resulted in only one conviction, and high level corruption in government and in elite anti-drug units appeared to be as pervasive as ever. Not surprisingly, the U.S. Congress was completely divided on certifying Mexico for 1999.

By February 1999, however, the Mexican government had begun the process of bringing charges against Mario Villanueva, the governor of the state of Quintana Roo, who had allegedly been a “protector” for the Juarez cartel on the Yucatán Península, which was a major transit point for Columbian drugs. Villanueva subsequently went into hiding and was believed to have fled the country. He was later arrested and extradited (in 2010) to the U.S. Also in February 1999, the Mexican government announced a new US$400 million, three-year plan to increase the funding and technical capabilities of its anti-drug efforts. Soon afterwards, the U.S. Congress certified Mexico for another year.

Despite economic and military action, Mexico seemed incapable of addressing serious institutional problems of corruption, and therefore had only marginal success in meeting U.S. objectives as set out in the 1986 Drug Act. Although the Mexican government made a major arrest or drug seizure at a timely moment to help the White House justify certification, ultimately the U.S. government had very little choice in the matter, even when the drug situation deteriorated. Not to certify Mexico would have disrupted trade relations and sent markets into a downward spiral, the effects of which would be felt throughout the hemisphere.

Members of the U.S. Congress became quite cynical about the “certification process.” Senator Christopher Dodd argued that “if we were to subject our own nation to this very test we apply to other countries, we wouldn’t pass it” (cited in Andreas, 2000: 70). Similarly, former Senator Carol Mosely-Braun declared the “certification process had nothing to do with the truth about narcotics enforcement.” Senator Robert Bennett went even further in his criticism. As he explained, “The certification process is a joke, if the purpose is to determine what is going on in Mexico.… We can’t de-certify Mexico. We have to lie about what is going on because our relationship with Mexico is so important that we can’t let it go down the tubes” (both quotes are from Andreas, 2000: 71). Dodd attempted to have Congress reexamine the law, but with little success.

The “certification process” appeared, then, to have another purpose, which was to create a forum for criticism of countries involved in the drug war and therefore to embarrass them into taking more effective action. But rather than leading to more effective strategies, like all unilateral strategies it poisoned relations between the United States and Mexico, and made it more difficult to create the necessary conditions for cooperative and integrative solutions. Recognizing these problems, the Mexican government pressured the United States into including in their Mérida Agreement of February 1999 a new set of Performance Measures of Effectiveness (pmes). The pmes were the first attempt by the two countries “to establish objective criteria to jointly assess their progress” in anti-drug efforts (pgr, 2000: 48). This is an example of the “strangulation” policy response by Mexico to limit the principled unilateralism of the U.S., in this case of the drug certification process.

Integrative-Principled: From The Hague And the Global to the oas and the RegionalAmong the oldest approaches to dealing with illicit international drug flows is the creation of drug regimes, representing attempts by participating countries to work together based on shared principles, information, and strategies that are clearly embodied in formal rules and decision-making procedures. Drug regimes often expressed mutual interest, and they provided some means of institutionalization and communication. But coordination (especially on enforcement) and capacity-building have largely been absent. Thus, they have rarely brought results or elicited more than token political support.

More than 100 years ago, Washington recognized the growing dangers of the opium trade with Asia and organized multilateral efforts to curtail its flow (Bruun, Pan, and Rexed, 1975; Taylor, 1969), along with complementary domestic legislation dating from 1909 (Walker, 1981: 15; Taylor, 1969: 130-2). It has consistently encouraged Mexico to join the new international regimes, which the latter did from the 1912 International Opium Convention in The Hague. This established the central principle of the international drug control regime to this day, limiting the production and use of drugs solely for medical and scientific purposes (Taylor, 1969:110-1; United Nations, 1987: 63). Subsequent Mexican cooperation was conditioned because it did not want “to expose to international scrutiny anything that might detract from the accomplishments of the Revolution,” yet it adopted strict measures that gave it “a drug control system exceeded in the Western Hemisphere only by that of the United States” (Walker, 1981: 45, 49). Even so, it was not committed to working closely with the United States, refusing to participate in the 1923 Pan American Conference, where the United States had urged the ratification and implementation of the 1912 Hague Convention. Washington refused to recognize that the Obregón government in Mexico had created a major obstacle to cooperation, with little trust having being established on the drugs issue.

From these early unsuccessful efforts at folding the bilateral relationship on drugs into a broader “principled” effort, a succession of ensuing initiatives followed. Each foundered, as ill-advised U.S. efforts to assert dominance were followed by Mexican withdrawal and a subsequent focus on bilateral relations. The first cycle of withdrawal began in 1925 and lasted until 1930 (Taylor, 1969:197-209 and Chapter 8).5 Among the Latin American countries that were important for drug control, only Mexico had made a serious effort to limit drug-related activity in this early period, even negotiating a multilateral extradition treaty with the U.S. and other Latin American countries in 1926 (Taylor, 1969: 290; Walker, 1981: 22, 35-7).

Mexico continued to pursue multilateral solutions itself and joined the first major drug regime in Geneva in 1931, which was the Convention to Limit the Manufacture and Regulate the Distribution of Narcotics. The terms of the Geneva regime reflected the view that the best way to deal with the problem of illegal production and distribution was by going to “the source” country itself, a policy favored by the U.S. (United Nations, 1987). Mexico predictably resisted this U.S. initiative, refusing to acknowledge that there was a problem of illicit drugs in Mexico, although domestic newspapers reported to the contrary (Walker, 1981: 70-71, 79-83).

Various drug regimes were created after World War II, such as the Paris Protocol of 1948 and the 1953 Protocol on Opium, but they did little to reverse illicit drug flows. In 1961, the United Nations General Assembly approved the Single Convention on Narcotics, which the United States did not ratify until 1967. Further conventions followed in the early 1970s, strengthening the U.S. position that cultivation and production were the primary causes of illicit drug flows and could be strategically dealt with independently of market or demand conditions (Bruun, Pan, and Rexed, 1975: 243-68). But with the onus and costs of the resulting drug strategies falling primarily upon producer countries, they proved ineffective.6 As Jack Donnelly noted, “Effective international action against drug trafficking would require relinquishing control over parts of the national law enforcement machinery. Virtually no state is likely to find this acceptable, given the centrality of the police power to the very idea of sovereignty” (Donnelly, 1992: 302).

Given that they tend to focus solely on production and supply, while overlooking consumption and demand, the drug regimes may have inadvertently driven up prices and ensured the huge growth in the drug market in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s (Del Villar 1989: 139). By 1988, the United States seemed to have acknowledged some of these underlying problems by giving support to the United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic and Psychotropic Substances (Nadelmann, 1990: 503; Donnelly, 1992: 291). The 1988 Convention criminalized illicit trading in precursor chemicals and the laundering of assets, and called for legislation to permit governments to seize ill-gotten gains. By 1993 more than 72 countries had ratified the 1988 UN Convention (Walker 1993-94: 64).

Over the years, there have been periods of a convergence of interests between the United States and Mexico, thereby leading to the creation of and support for drug regimes. Yet, most of these regimes have arisen from fundamentally different underlying concerns and so have not endured. For Mexico, the most salient issue was to have a drug regime that would constrain or limit U.S. actions; for the United States, the motive was more to enhance its international legitimacy, though Washington also benefited from the fact that regimes placed the burden on source countries. Independently of U.S. influence, the Salinas administration forged a number of multilateral agreements in the late 1980s, and, most importantly, signed the 1988 Vienna Convention. In the early 1990s, Mexico signed a series of bilateral agreements with other Latin American countries, including Guatemala, El Salvador, Colombia, and Venezuela, that were nominally aimed at improving intelligence-gathering, but in fact were aimed at preventing and/or regulating U.S. activities.

Mexico saw the advantages of multilateral cooperative efforts that were independent of U.S. participation. In 1993, Salinas called on Central and South American countries to develop new multilateral efforts toward fighting drugs that promised to protect the national sovereignty of individual countries (Tello Peon, 1996:127). Mexico’s intent was to establish an international legal framework beyond U.S. control. By early 2000, Mexico had signed 21 cooperative agreements to combat drugs with other Latin American and Caribbean countries. But regional regimes, like the 1990 Declaration of Ixtapa or the 1996 Anti-Drug Strategy in the Hemisphere, have been plagued by the same problems that have limited the UN Conventions: a lack of financial resources, enforcement mechanisms, and political support from member states.

Despite the generally understood need for multilateral solutions, the control of illicit flows introduces a whole new set of problems and issues that states have been reluctant to address because of their obvious implications for national sovereignty. Moreover, the United States, given its failure to lead effectively in formulating global regimes, has been hesitant to take the lead in the creation of hemispheric drug regimes because of its belief that bilateral strategies allowed Washington greater control and authority over its partners. It should be noted, however, that in 1999 the Organization of American States Inter-American Commission on Drug Abuse Control (oas/cicad) did begin developing a Multilateral Evaluation Mechanism (mem) (U.S. Department of State, 2000: 47-8, 608; pgr, 2000: 3, 64-5). The mem is a hemispheric peer review system intended to evaluate each oas member state’s anti-drug strategies and efforts. Its first evaluations appeared in April 2001, but to date it has not resulted in greater hemispheric cooperation.

Integrative-Operational: The Mérida InitiativeSeveral cases fit into this category, as outlined in Figure 2, including Operation Condor, a massive eradication campaign against heroin and marijuana that began in the mid-1970s, Operation Falcon (also known as the “Northern Border Response Force”), and the Mérida Initiative. In these cases, our four conditions of mutual interest (clear communication and coordination, institutionalization, and capacity building) are met. Again, space limitations preclude us exploring each case, and so we focus on the Mérida Initiative, the largest, longest, and arguably most important of these cases.

The militanzation of the war against the Mexican drug trafficking organizations (dtos) reached new heights following Calderón’s election in 2006. Some 40 000 military troops and 5 000 federal police were drafted to conduct operations within two years of his taking office (González, 2009: 74; Olson, Shirk, and Selee, 2010). The stakes for the U.S. remain significant, and the rationale for U.S. American support for Mexico is clear: U.S. interests are harmed by the instability, violence, and crime in Mexico because of the threat of spillover to U.S. soil and the impact it may have on immigration as Mexicans flee the violence. The 2009 U.S. National Drug Assessment Threat report claimed that dtos “represent the greatest organized crime threat to the United States” (cited in Vulliamy 2010: xxviii). The weaker the Mexican state is, the more likely it is that crime will spread.

Cooperation with the U.S. grew considerably under Calderón. A traditional arm’s-length interaction has given way to close coordination on extraditions and other criminal proceedings. The U.S. responded with the Mérida Initiative, a joint effort with Mexico (and several Central American countries) to combat drug trafficking, in which about US$1.5 billion was provided for Mexico. Most of these resources were targeted at counteracting the violent dtos by providing the Mexican security forces (military and police) with equipment and training.

Mérida represents the most important formal cooperation agreement on drugs between the two countries since the Binational Drug Control Strategy was signed in 1998, which funded programs to counter drug production and trafficking, strengthened the rule of law, and began systematically addressing the problem of money laundering. It marked the beginning of an improvement in cooperation levels, though results were mixed and corruption continued to pose an obstacle to effectiveness (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2007). Mérida’s funding ended in 2010, although the Obama administration has continued to seek monies for its programs. It has emphasized the importance of joint responsibility, sovereignty, and partnership -as equals-, all of which are important to Mexico.

Mérida was criticized for not addressing capacity-building and institutional reform (Ribando Seelke and Finklea, 2011). Thus, the post-Méinda strategy (known as Beyond Mérida, announced in March 2010) is noteworthy in that it extends cooperation beyond a hard-security (military and police) response to drug trafficking. It included four pillars: disrupting organized criminal groups; institutionalizing the rule of law; building a twenty-first-century border; and building strong and resilient communities. It represents a dramatic increase in support for civil society and institutional capacity-building through training programs for law enforcement and public engagement, among other things. The strategy represents an acknowledgement of the need for resources, cooperation, and multiple strategies in the fight against dtos.

Both Obama and Calderón have fully supported cooperation. In April 2011, the U.S. and Mexico agreed to increase joint intelligence gathering (dBuneNews, n.d.). In 2010, dhs signed an agreement with the Mexican Ministry of Public Security (ssp) to extend cooperation in joint border patrols in Arizona. ice and cbp have an agreement with Mexican counterparts to allow prosecutions that are declined by federal prosecutors in the U.S. to be taken up by Mexico’s federal Attorney General’s office (pgr). The U.S. is providing funding for judicial training, and also for state and local police, beginning in the state of Chihuahua. Its purpose is to “develop a standard curriculum for state and municipal police officers; to provide equipment, training, and advisors to state and municipal forces; and to help create a major crimes task force comprised of federal and state police” (Ribando Seelke and Finklea, 2011: 16 n. 75). usaid and the Department of Justice are supporting judicial and legal reform at state and federal levels. cbp is helping establish a customs training academy in Mexico.

The two sides have also cooperated in recent years on gun smuggling and money laundering. Estimates from the Mexican authorities place the number of U.S.-origin weapons seized in Mexico at 60 000 between 2007 and 2009 (Olson, Shirk, and Selee, 2010: 16). However, in some cases the lack of information sharing and unilateral action have led to problems. In Operation Gunrunner, for example, the atf was criticized for inconsistent information sharing with Mexican and U.S. agencies alike. It now maintains an office in Mexico City to provide Mexican officials with information from its eTrace gun-tracking program. In addition, ice is in charge of Operation Armas Cruzadas, a multi-agency effort to counter gun smuggling at the border. To address money laundering, ice and the cbp created Operation Firewall in 2005 to intercept illicit money shipments from the U.S. to Mexico. The two countries also created a Bilateral Money Laundering Working Group to coordinate efforts aimed at investigating and prosecuting money laundering and smuggling (Ribando Seelke and Finklea, 2011).

The militaries from the two sides are now slowly increasing cooperation, too, an unprecedented move for the Mexican military. Training and secondment of Mexicans to the U.S. have grown as a result of the increasing interaction of the Mexican military with its civilian counterparts, and also because of a growing understanding between the U.S. and Mexico on the need to cooperate (Ai Camp, 2010). Since Méri-da, U.S. agencies have increased their presence and activities in Mexico dramatically. Reports from Mexico indicate that arrests are up. In the 11 years from 1995 to 2005 (inclusive), there were 216 extraditions. In the five years from 2006 to 2010, there were 442. An anonymous Mexican government official stated that given the results, there was no reason for Mexico to oppose the presence of U.S. officials in Mexico (Esquivel, 2011). Thus, while sovereignty remains a concern, sensitivities can be ameliorated by paying careful attention to them and by strong results.

The U.S.’s acceptance of responsibility fostered trust. In addition to sharing an interest in outcomes, the Obama administration recognized that the U.S. shares responsibility for the problem of organized crime, including drug consumption, arms trafficking, and money laundering. Internal coordination and cooperation are also essential for effective cooperation. Incomplete access to federal data hampers coordination among federal, state, and local authorities, and some states have enacted more stringent gun tracing measures than others. Interagency and intra-agency cooperation have grown, but are also hampered by budget uncertainties and competition for funding, most of which is funneled through the State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics Affairs and Law Enforcement for security operations (Shirk, 2011).

The provision of resources for capacity building is also important. According to usaid officials based in Mexico City, U.S. expertise in law enforcement is key even if the level of funding is not very high (Capò and Real, 2011). The pgr also works closely with counterparts in the U.S., particularly in the Department of Justice and the Narcotics Affairs Section in State, to improve its performance. According to reports in the Mexican press, some nine U.S. civilian and military agencies have offices in Mexico and work on drug interdiction as a result of Calderón’s commitment to the drug war, including the Defense Intelligence Agency, Homeland Security, National Security Agency, the National Reconnaissance Office, the fbi, the dea, the atf, Coast Guard Intelligence, and the Office of Terrorist Financing and Financial Crimes. The most recent available figures suggest that about 500 U.S. agents in total now work in Mexico, up from 60 in 2005, and 227 in the first year of Calderon’s presidency (Carrasco Araizaga, 2011; Esquivel, 2011). From 2006 onward, a total of 54 agents from the dea alone operated in Mexico, with the consent of the Mexican government.

dea agents now operate alongside the pgr. They participate in arrests and interrogations and are able to collect and safeguard information. dea agents allegedly conduct interrogations at the Assistant Attorney General’s Office for Special Investigations of Organized Crime (Siedo) and the pgr (Carrasco Araizaga, 2011). Other participating or supporting agencies in Mexico include the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (see) and the ssp. Ironically, despite the worsening violence in Mexico, what Mérida shows is that an integrated-operational effort involving negotiated problem-solving strategies can deliver some strong results (measured as extraditions, capacity-building, seizures, etc.) without compromising the relationship between the two countries.

ConclusionA dynamic has emerged between the two countries that goes far to explain U.S. strategies and Mexican responses. Over time, and through trial and error, the United States and Mexico have developed a working -if inconsistent- relationship in dealing with illicit drug flows across the border. The so-called “rules of the game” are quite different for each side. If the United States is to gain the cooperation of the Mexican government in the drug war, it must respect Mexican sovereignty. Quite simply, protecting its sovereignty is Mexico’s most fundamental interest and its national security priority. Any unauthorized violation of that sovereignty will not be tolerated.

Whenever the United States has transgressed, particularly in its unilateral drug strategies, the Mexican government has been quick and blunt in its response and has attempted to “strangle” or preclude any recurrence. Such transgressions need not be merely territorial violations, for they may also be any act that undermines the internal or external legitimacy of the state. As Reuter and Ronfeldt explained, “The limits are apparently breached when the [U.S.] activity jeopardizes the revolutionary mystique and Mexico’s image at home and abroad, embarrasses Mexican leaders in power, weakens the central government or party control in some significant area, or get subordinated to non-Mexican actors” (1992:11). As the discussion of Washington’s unilateral policies has shown, they frequently do weaken and embarrass the Mexican government, and they always provoke a vigorous response.

A repeated problem is that Washington is frequently frustrated by the Mexican government’s lack of commitment and effort in carrying out its responsibilities in the anti-drug crusade. Of course, the United States holds Mexico to an unreasonably high standard of behavior in the drug war -one that the United States would, in most years, fail to measure up to itself. However, because of widespread corruption throughout the government and the prevailing sense that this is an “unwinnable war,” the Mexican government has demonstrated a high tolerance for drug activity within its country, as long as it does not challenge the authority of the state or embarrass the government.7

It should be emphasized that the illicit drug industry in Mexico has become so important that if it were to be fully shut down, the Mexican economy would undoubtedly suffer severe shocks.8 As the former personal adviser to Mexico’s attorney general has asserted, Mexico’s drug traffickers have become “driving forces, pillars even, of our economic growth.”9 Even so, when the national government has been threatened or embarrassed, it has inevitably taken strong action against drug kingpins and their organizations. Such aggressiveness is aimed not only at reestablishing the legitimate authority of the state, but also at projecting the appropriate image of “cooperative partner” to Washington. On the other hand, the United States recognizes the widespread corruption, and at times complicity,10 of the Mexican government in its handling of the drug problem. But there are also limits to U.S. tolerance, and when they have been exceeded, the United States has chosen to act forcefully and / or unilaterally, even though this has usually hurt U.S.-Mexican relations and, as we have demonstrated, often proven to be counterproductive when conducted unilaterally.

The drug certification process was a striking example of this counter-productiveness. Once the certification process was adopted in a fit of rage after the Camarena assassination, policymakers quickly discovered there was no going back; that it was virtually impossible to change the new law for fear of appearing “soft on drugs” (Andreas, 2000: 48). But it was also impossible to de-certify Mexico because of its close economic and geographic ties to the United States. To de-certify Mexico would trigger a crisis on both sides of the border that would have grave economic and political repercussions for both countries.11 Mexico knew this and acted with a certain level of impunity regarding U.S. judgments. It was able to supply the appropriate statistics of arrests and seizures to Washington to ensure certification, even if it made no real headway in the drug war. It also hired three major Washington lobbying firms to smooth the process and project the correct image of “cooperative partner” to Congress.

The certification process finally ended in 2002, and the U.S. moved toward a well-funded cooperative program under Mérida that fit the rubric of an integrative, multilateral solution. Mérida has shown that such approaches work far more effectively than unilateral action. The United States appears to have accepted that its narrow strategic approach of attacking only the source is counter-productive, sacrificing the credibility and goodwill of its most important anti-drug partner. The key message for policymakers is that identifying strategies that build on mutual interest, create channels of communication and coordination (both internally and cross-border), regularize contact, and build capacity will have a greater chance of success, because expectations will converge and trust will be built.

Over the years, the failure of U.S. unilateral policies and their ensuing Mexican strangulation responses have narrowed U.S. policy options. This has, in effect, forced the United States and Mexico into alternative strategies, which have produced closer and more cooperative efforts. The 1998 Bi-National Drug Strategy and its related Performance Measures of Effectiveness redefined the guidelines for both countries in combating drug trafficking. Procedures for cooperation between law enforcement agencies were further reinforced with the Brownsville Letter and Ménda Agreement. Mexico and the United States also supported the creation of an oas multilateral drug regime with its Multilateral Evaluation Mechanism. Whether the new post-Mérida Initiative will take hold and allow the United States to escape the perverse logic of its past strategies is a question that only time will tell. The development of these new strategies is certainly indicative of the failure of past U.S. drug policies, but unfortunately they are not necessarily indicative of future success.

The broader lesson to be drawn from this article is that the use of compulsory power unilaterally may have great political appeal at home, but it is often counterproductive, both in achieving U.S. America’s stated policy goals at the time and, just as importantly, in constraining its future options. The inevitable cycle, over time, leads the United States, the apparently dominant partner, to be further boxed in every time it enacts policy unilaterally. Ironically, perhaps, it ends up eschewing its own sovereignty and not Mexico’s.

It should be noted that the Mexican government did, however, extradite two Mexican national drug fugitives to the United States in 1999. See U.S. Department of State, 2000: 1, 12; Storrs, 1997: 1; and Anderson and Farah, 1999: A01.

In fact according to the Los Angeles Times, Mexico admitted that it had been informed of the operation two years before it occurred, although important details were not revealed, and, crucially, Mexico did not agree to U.S. agents operating on its soil (Kempster, 1998).

The September report was to include further evaluations on dismantling drug-smuggling organizations and progress in strengthening ties between U.S. and Mexican law enforcement agencies (Los Angeles Times, 1997).

The special anti-drug unit was created in 1997 in an attempt to reform the corruption-riddled federal law enforcement agency. It consisted of 100 investigators and officers and was part of an elite anti-drug agency known as the Organized Crime Unit operating within the Attorney General’s Office.

It should be noted that the United States did continue to cooperate with some regimes, such as the League of Nations’ Opium Advisory Committee, whose work dealt mostly with China and other Asian countries in this period (Walker 1993-94: 43).

As David R. Mares has pointed out, this strategy allows the United States to lessen its domestic costs while shifting the burden to producing countries (1992: 333).

As Andreas notes, the Mexican crackdown on drug smugglers during the Salinas administration was “highly selective/’ focusing on the so-called “old guard” who had ties to Colombia’s Medellin cartel, while allowing others to expand their operations (2000: 61-4).

As Nora Lustig has added, “The attempt to change the rules of the game too swiftly could trigger a wave of capital outflows large enough to threaten the fragile recovery [of the late 1990s]” (cited in Andreas, 1996: 165; see also Lustig, 1996; and Naylor, 1987).

The official, Eduardo Valle, resigned in protest in May 1994. His statement is taken from Mexican Insights (1995: 45).

An example of U.S. understanding of Mexican government complicity was starkly demonstrated immediately after the Camarena assassination when the U.S. ambassador to Mexico, John Gavin, provided a detailed and shocking description of the drug business in that country (cited in Walker 1995: 396; see also Shannon 1988: 204-213).

Few countries have been fully de-certified by the United States, and those were usually countries like Iran and Syria, which the United States had few important ties to.