The aim of this research is to demonstrate how the Italian fashion system began to take form in the inter-war period. The focus of the research is centred on technical and stylistic innovations implemented especially during the fascist period. The most important innovations were recorded in the field of footwear, female accessories and men's tailoring. The latter became a ground for experimentation with tailoring that led, in the long run, to the emancipation of Italian men's fashion from the secular dependency on the British. Part of the research has been dedicated to the man-made fibre industry set up in the early Twenties, thanks to which Italy managed to become more independent and needed to import fewer raw materials for the textile industry. The research was carried out by making a systematic examination of fashion magazines, and particularly male fashion magazines, until now rarely used for the study of Italian fashion.

El objetivo de este artículo es demostrar que la construcción del sistema de la moda italiana comenzó en el período de entreguerras. El trabajo se centra en las innovaciones técnicas y estilísticas realizadas principalmente durante el período fascista. Las innovaciones más importantes se registraron en los sectores del calzado, los accesorios femeninos y la sastrería masculina. Esta última llegó a ser un campo de experimentación que condujo, a largo plazo, a la emancipación de la moda italiana para hombre de la secular dependencia de Gran Bretaña. Parte de la investigación se ha dedicado a la industria de fibras artificiales establecida en los primeros años 20, gracias a la cual Italia consiguió ser más independiente y reducir sus importaciones de materias primas para la industria textil. El trabajo se apoya en un examen sistemático de las revistas de moda de la época, en particular de las de moda masculina, hasta ahora escasamente utilizadas para el estudio de la moda italiana.

Until the end of the Second World War, Italy, like all other Western countries, had to rely on foreign links both for women's fashion, which had been dominated by Paris since the 17th century, and men's fashion, which had been subjected to the sober, conventional British style since the end of the 18th century (Belfanti, 2008). In the historiography of fashion, the birth of Italian fashion can be dated to the first collective fashion show organised in Florence by Giovanni Battista Giorgini in 1951. International buyers, mainly Americans, were presented for the first time with exclusive models created by the most well-known Italian fashion houses (Pinchera, 2009; Vergani, 1992; White, 2000).

The goal of this paper is to demonstrate that, even though international recognition of Italian fashion came about during the Fifties, it was during the inter-war years that economic, institutional and cultural conditions created a favourable situation that led to Italy's success in fashion, paving the way for the affirmation of Made in Italy.

In the immediate years after the Great War, the institutional crisis of liberal democracy in Italy was marked by Benito Mussolini's rise to power in 1922, and for 20 years he influenced the civil, political and economic destiny of the nation. During the fascist period, the battles waged since the beginning of the century to create an independent Italian style were strengthened by the regime that saw in the emergence of a “purely Italian” fashion an important contribution to the construction of national identity. However, the root cause that initiated the construction of Italian fashion was due to the particular economic conditions of the time.

Furthermore, the elimination of free-trade by most Western nations, and the consequent limitation of international exchanges, made Italy pursue a self-sufficient economy and reduce imports drastically, which created a lack of many raw materials which Italy had in short supply (Mazzei, 1941; Zani, 1988). Although this, on the one hand, provoked a crisis in the textile industry and the production of luxury goods, on the other it stimulated the research for alternative raw materials, which brought about important innovations in the process and production of both textiles and fashion. Also concern over the balance of payments pushed the government to introduce restrictive measures against the use of foreign fashions. Not least important was the participation of artists linked to the Futurist Movement, as well as contributing to a receptive cultural climate for Italian fashion, participated actively on the creative level of designing innovative clothing and accessories.

Based on a chronological reconstruction covering the principle evolutionary stages of Italian fashion within the economic context of the time, this paper is divided into four sections. Each one analyses what, according to me, are the most important characteristics which fostered the creation of Italian fashion: the cultural and political climate which favoured the debate about Italian fashion; the artificial fibre industry which allowed Italy to be more independent of importing raw materials for the textile industry; the sartorial innovations in men's fashion; the accessories innovations in female fashion.

For the drafting of this paper, I have used as main source the fashion magazines published in Italy during the 20 years of fascism which make up an interesting documentation on what happened in the Italian fashion in those years. To these must be added sector publications like La Snia-Vscosa, founded in 1934, and other publications issued by the regime like Autarchia. Rivista Mensile di Studi Economici. Periodicals on men's fashion gained great importance like La Moda Maschile, founded in 1927 and Arbiter, founded in 1935. These provide an essential source for studying fashion for that period because, through a critical reading, one is able to appreciate not only the changes in the resistance of the Italian fashion system to it freeing from foreign fashion trends but also advances in women's and men's fashion during those years.

2In search of Italian fashionThe enfranchisement of Italian fashion from Paris began at the beginning of the 1900s, thanks to the pioneering initiative of the Milanese fashion designer Rosa Genoni, who presented her collection of clothes, inspired by the works of Renaissance artists, such as Pisanello and Botticelli, at the Milan International Exhibition in 1906, where she was awarded First Prize by the Decorative Art section jury (Fiorentini, 2004; Boneschi, 2014). Genoni's remarkable creativity travelled beyond national boundaries, and in 1909 the New York Herald began publishing her designs. Genoni's task went beyond her work as a designer and she took upon herself the responsibility of urging Italian institutions and fashion designers to become independent of France and let Italian creativity good taste and tradition emerge. It was also due to her commitment that in 1909 a working committee For a Fashion of Pure Italian Art was set up, presided by the textile manufacturer, Giuseppe Visconti di Modrone. Even if the initiative and support of the birth of Italian fashion was approved by institutions and saw the commitment of craftsmen and entrepreneurs in the sector, Italian design was still not ready to adopt a style that was too different from the diktat coming from abroad, and for some years Italian fashion houses would continue to present clothes inspired by French models. In the years immediately following the First World War, The supporters of an Italian fashion had to bitterly agree that “from the richest lady to the modest middle class person and even down to the ordinary woman, for years everyone of them believed that a dress couldn’t be admired if it didn’t follow the latest Paris fashion” (Hec, 1919).

In reality, as was noted (Grandi and Vaccari, 2004, pp. 41–43), things take on a different view if a difference way between “worn fashion” and “designed fashion” is considered. In the first instance it is concerned with fashion to satisfy home demand, and during the Twenties that meant the French style. Instead, designed fashion was thought of as being created by those who can be definited as artist-craftsmen, more attentive to understanding the needs connected to the debate between craftsman and artistic products which began in those years, and arrive at an independent Italian style.

In Italy, the first artist to make fashion a field of creative experimentation was Mariano Fortuny y Madrazo, who was a naturalised Italian of Spanish origin.1 In 1906, at Palazzo Orfei in Venice, his adopted city, he opened a small laboratory for printing silk where he created pleated dresses and cloaks coloured with vegetable dyes which gave the materials the look of sumptuous velvets. In 1909 he patented a polychrome print obtained by using natural materials like tincture of rubia to which he added some gold and silver powder made from copper and aluminium. The Knossos shawls and scarves became famous, inspired by Cretan art, but especially the Delfi dress, a copy of the chiton worn by the Delphi charioteer which was a cylinder of pleated silk enveloping the female body, and the peplos, a tunic that evoked the colours and lines of dresses worn by the Korai (Orsi Landini, 1991; Tosa, 1999).

The cultural climate and admiration for Fortuny's work aroused interest in artistic experimentation in fashion in another artistic designer: the Roman Maria Monaci Gallenga (Capalbo, 2012, pp. 82–86). She also dedicated herself to experimental research for new techniques of printing textiles and patented a particular technique that employed the use of coloured metallic pigments which shaded into one another, giving a shadowy effect. With this, she created soft furnishings but especially clothes and accessories that were famous in Europe and the United States between 1915 and 1935 and gained her recognition and awards in many international exhibitions. But as with Fortuny, Gallenga's clothes were unable to create a trend capable of marking a change in Italian fashion. They remained a sort of elite product and trend alongside the dominant fashion then present, and were worn only by rich aristocratic ladies or artists whose social position was matched by a strong personality.

Even so, Gallenga's artistic and entrepreneurial commitment during those 20 years helped to nurture the cultural excitement present in Italy about defining a national fashion style. In 1925, with the aim of promoting artistic art products abroad, she was, together with other artists of the time, the founder of the organisations Italian Modern Art Society and of the programme National Corporation for Craftsmanship and Small Enterprises. That same year her definitive international endorsement came about, thanks to a Grand Prix for printed velvets awarded at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris and a gold medal for bags. Thanks to this international recognition, in 1928 she opened the Boutique Italienne in Paris, which remained active until 1934. Her presence in Paris, capital of international fashion, highlighted even more the Roman couturier's talent, so much so that Gallenga was the only Italian to be invited to participate in the fashion show organised by the Foemina journal at Venice Lido in 1929, where her models paraded together with those of the most prestigious French designers: Hermès, Vionnet and Redfern. In the Twenties, the creative activity of the Roman couturier was linked with the cultural, political and economic climate in which the idea of the expression of an Italian style was adopted by the regime, which used it to affirm a national identity.

In the first decades following the First World War, signals that the initiatives for affirming an Italian style would take on a nationalistic format were clear with the first exhibitions organised around fashion. In 1919 the first National Congress of the Clothing Industry and Trade was held in Rome, after which it became clear that to carry out a transformation capable of inventing an Italian style, it would be necessary to set up a programme appraising the technical rather than the artistic aspect in fashion (Albanese, 1918). The congress closed with a programme to create a National Clothing Institute and an institute for fashion, which were never in fact set up.

One of the most enthusiastic supporters for Italian fashion at that time, the journalist Lydia De Liguoro also took part in this congress. Openly siding with fascism, in 1919 she set up the Lidel magazine, which became a militant press organ of the nationalistic culture (Gnoli, 2000). The artistic Futurist Movement also contributed to reawaken interest in the question of a national fashion, illustrating its ideas in various manifests published between 1909 and 1920 (Crispolti, 1986). However “fashion battles” (De Liguoro, 1934) still remained defined by militant figures and artistic environments.

However, even if Mussolini could congratulate himself on the nationalistic position adopted by the director of Lidel, until the Thirties there was no institutional position to support the birth of an Italian style, so much so that the press during those years continued to publish only illustrations of Parisian models and accounts of international fashion shows.2

This line was in accordance with the economic and political reality of the time. In the early Twenties, once post-war violence ended, the Italian economic system returned to the development model that had characterised Italian growth in the 15 years preceding the outbreak of the Great War, in the so-called “Giolitian era” (Toniolo, 1980, p. 31). The context in which the expansion of the Italian economy between 1922 and 1925 took place was that of an open economy and a liberal trade policy where the reduction of actual salaries, even though coupled with a reduction in the official number of unemployed, acted favourably to establish a positive cycle of exports–profits–investments–productivity–exports (Ciocca, 1975, pp. 354–355). In fact between 1922 and 1926, Italy signed nineteen bilateral custom treaties which reduced trade barriers (Toniolo, 1980, pp. 51–53). During those years, Italian exports increased by 9–10% annually, thanks mostly to the development of some relatively new productive sectors like the car industry, tyres, electronics, chemicals and artificial yarns (Tattara and Toniolo, 1975, p. 114). In the context of a political economy that still looked with interest towards the international market, it was not possible to think of closure with foreign markets, even in the field of fashion. Therefore, even though in the presence of some more “radical” positions concerning the passion for foreign things and the more or less expressed desire in the field of fashion to create a “purely Italian” style, Italy continued to import or reproduce French fashion.

In connection with men's fashion too, Italian tailors continued to take their inspiration from London. A classic example is that in Milan in 1922 a new magazine was established called Il Gentleman which, as it can be seen from its name, took its inspiration from the English. In the first number of this new periodical, the editor declared that space would be given to supporting Italian men's fashion and to “Latin brilliance” but that as an Italian style still did not exist in the male field, the magazine could not ignore what was happening abroad, in particular in England (Balabani, 1922).

Things began to change in 1926 when, due to inflation and the slump in the value of the lire, compared to the main foreign currencies, Mussolini decided to re-evaluate the lira with the famous “quota 90”. The re-evaluation of the currency penalised exports and marked a change in the regime's political economy in the nationalistic sense. This trend became more evident after the 1929 crisis, of which Italy felt in 1931 with a fall in prices, a reduction of currency in circulation, increased unemployment (Petri, 2002, pp. 92–97) and a drop in production, the volume of which was reduced by more than 33% (Confederazione Fascista degli Industriali, 1939, p. 75). This crisis brought about a re-enforcement of methods controlling imports in many countries. In Italy, between 1932 and 1934, various custom measures and a foreign commercial policy were introduced, aimed at controlling trade to prevent, or reduce to the minimum, the leakage of national currency. Between 1929 and 1934 the value of raw material imports dropped by 57%, semi-finished products by 65%, while the curtailment of exports was 71% (Confederazione Fascista degli Industriali, 1939, p. 78). In such a climate of shutting down international markets the decisive change, officially sanctioning the beginning of an autarchic economic regime, took place in 1935 when, due to the government's decision to invade Ethiopia, the League of Nations imposed economic sanctions on Italy which, even though cancelled in July 1936, legitimised Mussolini's decision to launch a plan for self-sufficiency. It was during the early Thirties that fascist interest in the birth of an Italian style became active and it was inserted in the “emancipation of Italy” project, which planned to project an image of a nation with a strong identity, which fashion could help to create (Paulicelli, 2004, p. 75).

The regime's commitment to create a national style was also due to an economic problem after an investigation on trade, carried out in 1931, revealed that Italy imported from France clothing that amounted to billions of lire annually and took about a third of the French exports (De Liguoro, 1932). Therefore on 22 December 1932 a law was approved to set up an autonomous body for a National Permanent Exhibition of Fashion. At the same time, the regime requested Italians to “dress in an Italian manner” (Giordani Aragno, 1991, p. 87). What happened was that after the first National Exhibition of Fashion, which took place in Turin on 12 April 1933, it was evident that the organisation had many structural shortcomings and deficiencies in the creative and industrial field (Gnoli, 2000, pp. 63–65). Therefore, on 31 October 1935, the National Body for Fashion (Ente Nazionale della Moda) was set up, which substituted the previous one. It was given full powers of control over the production of national fashion: not only were all dress designers obliged to declare their activities to the body but 25% of the creations made by the designers, who were entered into the register of Italian fashion design, had to be carry an official stamp given by the body which assured it was wholly Italian. The authority also tried to create incentives for sartorial experiments, identifying with a golden seal those laboratories capable of producing original creations and using textiles made from national raw materials (Capalbo, 2012, p. 103). There was an awareness that to create an Italian style, it was necessary to have a textile industry capable of facing foreign textile competition and therefore able to furnish a quality product (Paulicelli, 2004, p. 75).

The inadequate production of Italian cotton and wool had made Italy partly dependent on foreign suppliers for raw materials. Until the Thirties crisis, the wool industry largely took their supply of wool from overseas, but the beginning of self-sufficiency had imposed a rigid control on trade, curtailing imports (Fontana, 2003, p. 358). The same thing had happened in the cotton industry. Since 1935 the government had imposed strict limitations on imports of lint cotton or raw cotton and tried to increase the cultivation of cotton in Sicily and Italian Somalia, but this was not sufficient for the needs of the textile industry (Fumi, 2003, p. 424). Therefore the first fundamental step taken by fascism was to provide incentives for the production of substitute raw materials and support the beginnings of the artificial fibre industry.

3A logical product of progress: artificial fibres placed at the service of fashionIt can be said that initially fashion autarchy was concentrated on problems linked to the lack of raw materials for the textile industry. First it was necessary to re-evaluate local resources, starting up again the production of orbace, a rough but resistant wool typically Sardinian, and the traditional woollen material from Casentino in Tuscany. Great importance was also given to the production of natural fibres from hemp, mulberry and juniper leaves. Also to be mentioned are ramia and esparto grass. The first is a nettle family plant which can be combined with wool and linen; the second is extracted from a grass which, after working, can substitute jute. But the real answer to the lack of raw materials came from chemical research – in which also the National Research Council was involved – and the consequent invention of man-made fibre. It was in the production of artificial fibres, especially rayon, that capital-intensive companies emerged in the inter-war period, introducing various improvements in the process and product, which were able to supply not only the Italian textile industry, but also to corner the international market.

The most important Italian artificial fibre factory was Snia-Viscosa, founded in Turin by the entrepreneur Riccardo Gualino in 1917. The original business of Snia (Italian-American Shipping Company) was to sail the oceans searching for supplies for the country (Spadoni, 2003). In 1920 a serious crisis in the maritime freight market caused the Board to convert the company to produce artificial fibre textiles that came from cellulose and, in particular, rayon. In 1922 the name changed into Snia-Viscosa (National Society Viscose Industry Applications). In the following years the company continued to expand, taking over the control of other Italian companies specialised in the production of rayon (Unione Italiana Fabbriche Viscosa, Viscosa di Pavia, Società Italiana Seta Artificiale). At the same time the company integrated vertically, acquiring majority shares in Rumianca, a production company for chemicals indispensable in the fabrication of artificial yarns, and in Silm, supplier of plants and machinery necessary for the production of rayon. These investments enabled Snia-Viscosa to participate in the international expansion phase of the new technology of man-made fibres.

In 1925 the quantity of artificial fibres produced by Snia-Viscosa reached 43,000 tonnes a day, equal to 70.3% of the Italian production, 16% of the European production and 11.3% of the world production (Berta et al., 2013, pp. 588–590). In the period of the opening of the international market in the early Twenties, the Turin group extended its field of action to overseas both through exportation as well as direct penetration, opening branch offices and factories. At the beginning of the Thirties, Snia-Viscosa owned six companies abroad, including the USA (Spadoni, 1999–2000, p. 107).

Rayon, which initially was called artificial silk, had caused a great revolution in the world of textiles and clothing because it became possible to substitute the more costly silk, in respect of which the production cost was between one quarter to one third for the 20 year period (Federico, 1994, p. 427). The contribution that artificial fibres made to Italian fashion was not only the possibility of substituting rayon for natural raw materials which were usually imported, but that thanks to their use, it was possible to introduce important commodity innovations in the fashion field.

Initially rayon yarn had a large count (200–300 denier) and had to be mixed with wool to obtain different colour effects, but after 1920 technical innovations permitted the use of ever-finer threads with which it was possible to produce, for example, underclothes (Garofoli, 1991, p. 24). However the most striking success of man-made fibres in fashion was in the production of women's stockings, beginning in the early Twenties. At the beginning of the century, women wore rather thick stockings made of cotton, linen or hemp; the costly silk stockings were luxury products. Stockings made of artificial silk provided the majority of people with an economic product. A later innovation occurred in 1927 with the opening of the Società Seta Bemberg, which added to the viscose procedure in rayon production and produced cupro thread, which was more resistant than rayon as well as partly solving the inconvenience of laddering, improving even further the production of women's stockings, and giving a look very similar to natural silk (Capalbo, 2012, p. 106).

A further reason for using artificial fibres in clothing came in the Thirties with the introduction of run-resistant knitwear which, combined with its pleasant look and ease of washing, contributed to the success of rayon, especially in the production of female underclothes (corsetry, brassières) and swimming costumes (Garofoli, 1991, pp. 27–31). Then the main groups working in the Italian market decided to start experimentation with a new fibre which could be combined with, or substitute cotton, wool and linen: and so came into being the so-called short or tufted fibre (Spadoni, 1999–2000, p. 46). It was one of the most important innovations in the field of artificial fibres and influenced the clothing industry in an important manner. The tufts of rayon could be cut into preset lengths and then mixed with cotton or wool. With these tufts some defects could also be resolved, like the variations in the weight of the yarn, the difference of length and toughness, the breaking of the elementary fibre, the difference of shades in dyeing and bleaching (La Snia Viscosa, 1958, pp. 35–36). Also, if production of the old type of rayon did not permit the use of cotton or woollen production plants, the production of tufted fibre employed spinning and weaving systems which could be used for any natural fibres, and therefore the adoption of communal productive processes for dyeing and spinning: which facilitated the use of blending or use of rayon as a substitute for cotton (Catronovo and Falchero, 2008).

In the production of tufted fibre, the greatest contribution came from Snia-Viscosa which placed on the market a new short fibre called sniafiocco, which blended with wool, cotton or silk as imposed, among the others, by the autarchic directives of the regime. Between 1934 and 1935, the Snia-Viscosa became the biggest producer in the world of tufted fibre (Catronovo and Falchero, 2008).

The search for an artificial fibre to replace natural fibres did not stop at viscose. In 1935, the scientist Antonio Ferretti invented a method of manufacturing a yarn very similar to wool: lanital. This new artificial fibre provided Italy with the opportunity to reduce its importation of wool and use a national raw material, casein, which came from milk. The production of lanital was immediately taken up by Snia-Viscosa, which patented it (Spadoni, 1999–2000, p. 25). In 1937 the Snia plants produced 7 million kilos of lanital. But it was the company of Cisa-Viscosa, which passed into Snia-Viscosa's control in 1939, which produced cisalfa, which was also a substitute for wool (Fig. 1). Contrary to lanital, cisalfa was made of both celluloid and protein substances and conserved the resistance of the vegetable fibres and ease of dyeing, felting, rendering the warmth and softness of wool. It was totally produced in tufted fibre, given its exclusive use in a wool mix (Benelli, 1937).

Overall, in the Thirties the domestic consumption of artificial fibres grew significantly, rising from 20,000 tonnes in 1934 to 84,100 in 1938 (Spadoni, 1999–2000, p. 46). In particular, the production of rayon marked an increase during the whole period between the two world wars. In 1922 it amounted to 3 million kilograms, which became 28 million in 1931 and 50 million in 1938 of which it exported half. In this same year rayon was produced in 14 factories employing about 20,000 workers (Baglia Bambergi, 1939). The production of tuft reached 70–80 million kilograms per year (Italviscosa, 1939).

Taking into account lanital and other minor fibres, the total Italian production of man-made fibres in 1938 reached 128 million kilos (Autarchia. Rivista Mensile di Studi Economici, 1939, p. 40).

The production of artificial fibres made a notable contribution to the self-sufficiency target, reducing the importation of two principle textile fibres: from 1929 to 1939, cotton imports dropped from 240,000 tonnes to 120,000, and wool from 64,000 to 32,000 (Maiocchi, 2003, p. 76).

To encourage the Italian consumer, who initially showed a certain reluctance towards clothes produced from self-sufficient textiles, the biggest companies in the sector made great use of the media through photos and designs published in women's and family magazines, and a campaign carried out through bill posters, using original artists like Marcello Dudovich who created the most sophisticated illustrations of the times. In ladies’ journals photos appeared showing beautiful models and famous Italian actresses modelling Bemberg stockings, Snia-Viscosa rayon and lanital. The persuasive power of the publicity campaign was very clear to those working in the sector and to the Ente Nazionale della Moda Italiana, which wrote in its official organ (Rassegna dell’Ente Nazionale della Moda): “For the campaign in favour of national textiles … it is not sufficient to repeat ‘national textiles are excellent’, ‘the new textiles are wonderful’. In our modest opinion the springboard for an efficient campaign of this sort is the following: to affirm that synthetic fibres and the resulting textiles are a logical product of progress” (Merli, 1939).

4Dress in an Italian style. Fashion in the period of autarchyAs it has been already mentioned, female magazines played its role in supporting national fashion. Already in 1934 in the nationalistic afflatus that reigned in fashion, some magazines started to leave out designers of French fashion, whose designs, however, they still published. In fact, some magazines approved the benefit of gathering what was truly creative abroad, so long as the manpower and materials were Italian (Carrarini, 2003, p. 820). Parisian fashion designers were therefore still taken as reference models to improve the national product, so much so that the popular illustrated news magazine Dea published an article in 1935 entitled Dea interviews the great designers, in which it compared the style of some designer labels in Italian fashion like Fercioni, Bigi, Radice, with models of the most well-known French designers, like Lelong, Molineaux, Patou, Schiaparelli, and Palmer (Dea, 1935, pp. 27-28).

The condemnation of a cosmopolitan fashion was radicalised in 1937 when it emerged that of the 4 billion deficit in the balance of payments, 2 billion were not used for the importation of raw materials but luxury goods, jewellery, furs, costly textiles and haute couture fashion (Aspesi, 1982, p. 87). It was in the same year that fashion magazines began to publish only Italian designer models, some of whom developed such a well-known identity that they were introduced as authors of original models (Lupano and Vaccari, 2009).

In the world of design, there were many designers who were distinguished by their ability to free themselves from Parisian imperialism. In Florence in 1932, the city's fashion designers had presented their own original models at the Primavera Fiorentina exhibition. In Milan, autarchic fashion carried the names of Carla Tizzoni, Germana Marucelli and Ventura. In the capital the biggest names in national fashion were the Botta Sisters, Giovanni Montorsi and Nicola Zecca. This last named was among the first designers to declare in favour of a national style, becoming the promoter of a rigorously Italian product. Thanks to the pioneering courage of Zecca, in 1937 there was a preview of Italian fashion in the USA when, on one of her trips, the Countess Cora Caetani took clothes that were entirely Italian made, and she was photographed in Vogue America wearing a dress by Zecca in lanital (Capalbo, 2012, pp. 114–115): another proof that in Italian female fashion the real novelty was the use of new materials produced from artificial fibres.

Feminine attire did not undergo such shocking changes in the Thirties compared to those which hit women's fashions in the Roaring Twenties or like models carrying the Parisian designer labels of the calibre of Chanel, Sciaparelli, Vionnet. From the stylistic point of view, the only changes made were the shortening of hems which were raised from the calf to just below the knee, and the marked use of furs (Gnoli, 2000, p. 101) which, like materials, became rigorously autarkic: lamb's wool camouflaged to look like beaver, rabbit dyed to look like leopard, otter or Persian. Cat's fur and even coloured mouse's fur were also used (Rassegna dell’Ente Nazionale della Moda, 1939, pp. 29–32).

The true sartorial innovation came about in male clothing, usually considered immune to fashion changes. In fact, since the beginning of the nineteenth century, with the spread of the British model of elegance, which consisted of three pieces (jacket, pants, gilet) throughout the whole Europe (Kuchta, 2002), male clothing was no longer subject to changes in fashion as in previous centuries. The elimination of the decorative element in male clothing, which in 1930 would be interpreted by the psychologist Flügel (2003) as the great masculine renunciation of fashion, contributed to shift completely the attention on female fashion (Riello, 2012, pp. 62–64). In fact, male clothing continued to be modernised and modified, although at a slower and less obvious manner than female clothing. The changes in men's fashion are reflected not only in the essential accessories (hats, gloves, ties, etc.) and in the choice of fabrics, but, above all, in the modification of the contour of pants and outwear. This in particular placed male clothing on an evolutionary path different from that of female clothing, focusing particularly on the importance of the design of clothing and cutting. The idea of tailoring as a scientific and design discipline, which required continues modifications, was gradually being affirmed. To this end, in 1848 in Milan the publication of Il Giornale dei Sarti was initiated, which would be a tool of important updates for the Italian tailors until the Eighties of the 19th century (Franzo, 2005). However, it was in the years between the two wars that publications of specialised magazines, sartorial treaties, cutting methods, measuring techniques increased (Lupano and Vaccari, 2009). In these publications, particularly during the Thirties, the search for a typically Italian style was joined, that would make men's clothing independent of the British style, which from the beginning of the nineteenth century had a monopoly on international men's fashion.

The changes and innovations which Italian male fashion underwent were however, without doubt linked to the declared determination to create something different from the English style, which would mirror the image of the fascist “new man”. The male prototype proposed by the regime was that of a virile man whose manhood was obvious, not only in his manner of dressing in a sober and dynamic style, but also a physique forged through sport, the practice of which became widespread during the Twenties. The search for greater practicality in dress represented the real attempt to differ from the British style. Futuristic avant-garde ideas helped to create a favourable cultural climate in male fashion. If, since the end of the Twenties, artists like Giacomo Balla, Fortunato Depero and Enrico Prampolini had indulged themselves by creating and wearing jackets, cravats, waistcoats and shirts which were produced only by artistic-craftsmen – often made up by their wives and daughters and not destined for the public (Giorgetti, 2014) – some futuristic authors collaborated with the fashion industry, designing clothes for general production. One of the main futurism contributors to fashion was Thayaht (Ernesto Michahelles), who published an article entitled Dress in the Italian Way in the Oggi e Domani magazine. In 1932 he signed the Manifesto to transform male clothing, in which a varied range of models was proposed for a radical reform in men's clothing which should be comfortable, tasteful and able to better fulfil the needs of modern life (Garavaglia, 2009, p. 224).

Differing from most of the other futuristic artists, who were separate from the industrial system and technical aspects of production, Thayaht had gained important experience both in the field of Parisian fashion, collaborating from 1915 to 1925 with maison Vionnet for whom he had illustrated models in the Gazette Du Bon Tonne, as well as in American fashion, collaborating with Vogue magazine and with the department stores of Wanamaker and Altman (Garavaglia, 2009). In the Twenties, as well as writing and illustrating for L’Industria della Moda magazine, he carried out important work in various publicity campaigns promoting Italian products like the straw industry in 1927, which was reintroducing the very Italian straw boater to the national market (Caputo, 2008). His name was linked to the invention of Tuta, which was published and launched in the Florence newspaper La Nazione on 17 June 1920, attaching a paper pattern to facilitate reproduction, and which was such a great success with the public that in only ten days more than a thousand paper patterns were bought (Pratesi, 2008). The particularities of the Tuta were in the design that followed a simple but very rigorous geometric outline, concentrating on the double dimensionality of the material instead of the shape of the body. Thayaht also designed a female Tuta with a skirt: a sort of man's long shirt, partially buttoned in front and worn with a tight belt at the waist. Thayaht collaborated with Madeleine Vionnet on a more sophisticated version of the female Tuta, which the Parisian designer patented and presented to the French public in 1922 (Morini, 2008).

The need for renewal in men's fashion found space in the sector's periodicals which became, the debating place of sartorial innovations, aiming at simplification and greater comfort in clothing. With the aim of encouraging Italian designers to create an innovative male fashion different to the English one, magazines engaged top artistic designers who were entrusted with drawing figures as prototypes for sartorial reproductions (Soresina, 1935). In this context the growing culture of design joined that of fashion in the need to upgrade the identity and originality of the Italian product, and fashion design emerged as one of the most original and significant aspects to reinforce the still fragile identity of Italian fashion (Lupano and Vaccari, 2009). The first periodical to undertake the circulation of the Italian figure was the magazine Lui, founded in 1927. In fact, each edition was produced in two ways: one destined for public readers, the other more technical one for tailors. But the most important contribution to the circulation of the figure campaign was in 1935, when the title changed its name to Arbiter, becoming the interpreter of the autarkic change, so much so that the declared aim of the periodical was to banish any reference to the excellence of English fashion (Magnani, 1935). Many designers collaborated with Arbiter, proposing proper technical tables to be used by tailors like Saverio Spagnolo, an expert in sartorial technique, thanks to experience gained from working in various Roman tailor's shops (Una bella giacca estiva ed una breve discussione tecnica, 1943; Questa è la moda, 1940).

During the autarchy years, the proposals published and finalised in sector journals to innovate male fashion were very varied, like that of substituting trouser buttons with the more practical zip, which was adopted by numerous tailors (La chiusura lampo, 1936; Il signor Marchesi dice che, 1936). With the idea of more comfortable clothing came the inspiration of substituting the shirt's starched collar with floppy collars, even if that was an English inspiration (Paris, 2006, p. 66). Some companies in the sector took up the challenge to search for a system to produce less rigid collars but which were structured to avoid crumpling. The company MIB, Italian Manufacturer of Underclothing, in 1935 patented a special material for collars characterised by four zones of different thicknesses; in 1937 the Textiloses & Textiles SA in Milan created the Indeformex material, to be inserted inside collars so they had the elegance of a starched collar but retained the comfort and simplicity of a floppy collar (Novità nel corredo maschile, 1935; Un segreto svelato, 1937). In the same year the American company Trubenis put on the market the floppy collar Unitez (Un nuovo colletto, 1937).

However the most interesting designs and innovations concerned jackets, that most masculine piece of clothing. The English jacket was considered rigid and not very comfortable for a dynamic and sporting man celebrated by fascist culture. Therefore in the Thirties most designers and tailors concentrated on designing a new jacket. The Lui magazine, in its first number in January 1933, published a design for a jacket attached to pants with a thin elastic belt to avoid the “blouset” look, especially for sporting men who did not wish to lose their elegance (La biancheria degli sportivi eleganti, 1933). In February of the same year, a figure was published giving the jacket a small belt at the back which made it possible to pull in or let out the jacket at the hips (Consigliamo ai nostri lettori, 1933). The Arbiter magazine continued to promote innovations which gave men's jackets a greater rationality and sporting look, like the proposal to eliminate the collar lapels on outdoor jackets, which gained much approval from tailors and readers (Al di là delle vecchie consuetudini, 1938).

One of the most successful innovations was the Safari jacket which in Italy was simply called sahariana. Of uncertain origin, but diffused on the African territories colonised by the British, it was characterised by four pockets in the front, open collar and a belt at the waist. Proposed for the Italian army during the Abyssinian war, the Sahariana jacket, made of linen, cotton or gabardine, during the Thirties, was launched by the Italian designers as was one of the fashion pieces in men's wardrobes for everyday use (Grandi and Vaccari, 2004, p. 210). The success was immediate, so much so that it was appreciated also abroad and was published in two of the most important American and German magazines of the time: the Das Herrenjournal and Apparel Arts (La giacca Sahariana, 1937). In 1938, in the magazine Il Piccolo it was written: “It is gratifying for us to see that in America, where the convenience and comfortable simplicity of menswear is not separate from a certain elegance, the sahariana, the indisputable Italian creation, has been a so absolute and unconditional success in all the social classes”.3

A fundamental innovation in men's clothing came through research undertaken by various tailors to improve cutting and measuring techniques (Capalbo, 2012) in the wake of a tradition going back to the previous century, when the tailor Basile Scariano, in 1855, had published a treatise on the principle of triangulation of clothes cutting (Davanzo Poli, 2003, p. 552). In 1933, the Milanese tailor Bruno Piergiovanni had an idea which he patented – also for women's clothes – of a mechanical device called Pi-no-stop (Lupano and Vaccari, 2009, p. 19), with which exact measures could be taken. It was easy to use and not very large, being made of an adjustable metallic square ruler of 25 centimetres (Peterlongo, 1934). The other measuring system called Plastes was patented in 1940 by the Roman tailor Luigi Branchini. It was a metallic cage which wrapped around the body, registering any “disharmonies” of proportion and determining a corresponding movement of projections and ratios, which allowed the tailor to create a harmony in the form of the outfit (Un nuovo sistema italiano di misurazione per la sartoria maschile, 1938). The success of Bianchini's method crossed national boundaries and became appreciated by English tailors too and published in the London Alliance journal in 1938. But the tailor to whom is owed the success of Italian men's fashion was the Roman, Domenico Caraceni. Thanks to a study of English works on cutting and the possibility of “handling” English clothes in his father's tailor's shop in Abruzzo, he modified the English tailors’ blueprint for jackets, eliminating the rigidity and giving it a sort of internal structure (Caraceni, 1933). His clothes combined aesthetic pleasure and a perfect cut together with the “lightness of a handkerchief” (Vergani, 2004). It has been necessary to wait until the 1990s for another “restructuring” of men's jackets, the work of the designer Giorgio Armani.

Italian men's fashion during the inter-war years also knew how to revitalise itself on the chromatic level, and this was also due to an important contribution by the futurists. In 1914 Balla published The Anti-neutral Dress manifest. Anti-neutrality, which for the futurists meant supporting Italian intervention in the war, was projected as anti-neutrality of colour in fashion, connected to the struggle against middle-class mediocrity. Its geometric and brightly coloured materials were therefore in line with the manifest declaration: “We want to colour Italy with daring and futurist risk” (Crispolti, 1986). Later, in 1933, Tommaso Marinetti, Francesco Monarchi, Enrico Pampolini and Mino Somenzi signed the Futuristic manifest on Italian hats, in which the Nordic use of black or neutral colours, reflecting snowy, foggy or wet streets in a stagnant melancholy was disapproved (Marinetti et al., 1933). Colours were suggested for another important male accessory: the cravat. In the futurist manifest on Italian cravats we read: “the anti-cravat supported by a light elastic collar, reflects the sun and blue sky with which we Italians are blessed and eliminates a melancholic and pessimistic note from our men's necks” (Di Bosso and Scurto, 1933).

The creators of men's fashion made use of these ideas and although men's clothing should eschew any frivolity because male elegance should be a synonym of virility and discipline (Le nostre idee sull’abbigliamento, 1935) the separation from the English style in the last years of the regime meant choosing colours in contrast to the muted tones of English tailoring. For grey, black and navy blue, Italian tailors began to substitute colour, which did not go beyond the limit of good taste but bestowed on male clothing a distinctly Italian look because inspired by the sun and Bel paese colours. Among the foremost textile companies that introduced colour in textiles for male clothing, Brummel of Turin stands out, launching in 1937 the colour of blue Mediterranean and in 1938 Siena earth, a delicate brown shade (Terra di Siena, 1940).

But if male fashion in this period became an interesting field of experimentation and innovation, the Italian figure contributing to the renewal of female fashion occurred particularly in the accessory sector, where the experimentation and use of innovative materials were linked to the design of products aimed at mass production.

5Female accessories open the way to Made in ItalyIt has been said that women's haute-couture in the inter-war period did not reach a level of originality to compete with the French. Artistic memories of past or traditional costumes, dear to the regime, were not as alluring as stylistic proposals by Parisian designers. It was mainly in accessories, experimentation items for new materials, shapes and polychrome, that Italian fashion was able to express its talent and creativity and gain the first Made in Italy successes during the years of autarchy.

An original contribution in the accessory field came from designer Uberto Bonetti, part of the second wave of Futurism: the Aero-futurism, which influenced his work both in colours and graphic symbols in the materials designed for clothes, but especially ties, cravats and scarves, which evoked different shades of sky blue enlivened by multicoloured flashes (Giorgetti, 1998). With Bonetti the study of fashion accessories led to a definite design which became a prototype, created to be mass-produced. Proofs of this are sketches made for Villa of Milan and Corsi of Florence during the Twenties and Thirties (Bonetti, 2014). In line with the reassessment of self-sufficient materials for female accessories he used not only raw plastic and synthetic resin derived from casein and bakelite produced in three laboratories situated in Turin, Milan and Ferrania (Confederazione Generale Fascista dell’Industria Italiana, 1929, p. 288), but also aluminium, which was still rare and costly but present in Tuscany following the nascent aeronautic industry (Giorgetti, 2012). With plastic or bakelite materials Bonetti created jewellery and original necklaces-breastplates which embellished his evening house-dresses (Giorgetti, 1998). Also, in accordance with the regime's self-sufficient line aiming at a fashion inspired by traditional regional costumes (Gnoli, 2000; Paulicelli, 2004), Bonetti studied traditional clothes and costumes of many Italian regions, particularly cloaks, jewellery and embroidered decoration, taking models and useful elements for mass reproduction and destined for fashion houses (Giorgetti, 1998).

Many Italian craftsmen like Giuliano Fratti, called the “king of crazy jewellery”, dedicated themselves to costume jewellery and other female accessories. At the beginning of the Forties, when the war made it even more difficult to obtain materials to create bijou and other clothing accessories like jewelled buttons, Fratti managed to create original pieces of costume jewellery, as well as buckles, buttons and trimmings, using poor materials like cork, straw and corncobs which were delivered to fashion houses all over Italy (Giordani Aragno, 2004).

The most important accessories for female outfits were however bags and shoes, the latter coming into fashion through shorter skirts in the years following the war. It was especially with these two accessories that the ingenuity and inventiveness of Italian creators captured international fame, putting the feared Paris in the shade. The “dream shoemaker” who innovated women's footwear during the inter-war years was Salvatore Ferragamo. He had studied shoemaking since he was very young in his birthplace of Bonito, near Naples. At only 14 years of age, he joined his emigrant brothers in the USA where, a few years later, his fame began when he opened a shop in Hollywood and became the American star system's shoemaker.

Understanding that the most important aspect of improving women's footwear was to make it more comfortable, he took a foot anatomy course in South California University. Thanks to these studies he understood the importance of strengthening the planetary arch which supports the body's weight. His first innovation in women's shoes was to insert a steel foil (cambrione) in the narrow underfoot part between the heel and the sole, corresponding to the planetary arch, to support the body weight without causing bending (Ferragamo, 1957). The demand from sophisticated American clients increased over the years as well as from department stores like I. Magnin of San Francisco and Saks Fifth Avenue in New York (Ricci, 2007), necessitating an increase in production. But America lacked specialised manpower in handmade shoemaking. So Ferragamo returned to Italy in 1927 to produce handmade shoes for export to the USA. Leather craftsmen tradition led him to open a laboratory in Florence where he gathered a hundred or so specialised staff from all over Italy (Ferragamo, 1957, pp. 110–120). In the Florentine laboratory, Ferragamo combined the American production process in the shoemaking industry with hand work, creating a human assembly chain. He also used the American measuring system, which provided a variety of sizes to correspond not only to different lengths of foot but also different widths (Ricci, 2007). But it was in the years of autarchy, when first class materials disappeared from the market, that Ferragamo's brilliance found a constructive solution and created new fashion trends. Towards the end of 1936 the best steel used for the cambrione was commandeered for the Ethiopian war. The remaining steel was of poor quality and split. So he invented the Orthopaedic shoe with the sole made of Sardinian autarkic cork. Building on this constructive solution he lifted the heel and gave the planetary arch a stable support, resolving in a fantastic and brilliant manner the lack of steel. The cork heel, patented in 1937, was an enormous success and was imitated by shoemakers all over the world, so that in less than 2 years since his invention, 86% of women's shoes made in the USA had wedge heels (Ferragamo, 1957).

The orthopaedic heel was followed by many other types of wedge: a heel, a platform of curved and pressed levels, chiselled and painted, decorated with pieces of glass in imitation of the ancient mosaic technique (Ricci, 2007). Like great modern industrial designers, Ferragamo created the shape of his shoes, starting from their functionality but following them through a continuous aesthetic research which he translated into the use of alternative materials, from the richest, finest and recent to the most traditional. He made heels by sewing together cork bottle stoppers and covering them in leather: patenting special procedures for the production of surrogate leather; he invented transparent bakelite heels and wooden adjustable soles in Galalith or glass which imitated machine wheels or cotton reels. As alternatives to leather uppers, he used plaits made of hat straw, lacework, hemp material or woollen yarn. Even by looking at the paper used to cover chocolates, Ferragamo found another solution for a singular creation of the upper: he took thin twine and plaited it with threads of silver and gold. Among the numerous awards received by him is the Neiman Marcus Award in 1947, won for his invisible sandal with the upper made in nylon thread. The Italian shoemaker was well aware of what was happening in design and the art world, enlisting the creative participation of a contemporary futurist artist, Lucio Venna, who was entrusted with the publicity campaign and printed logo on shoe labels (Ricci, 2007).

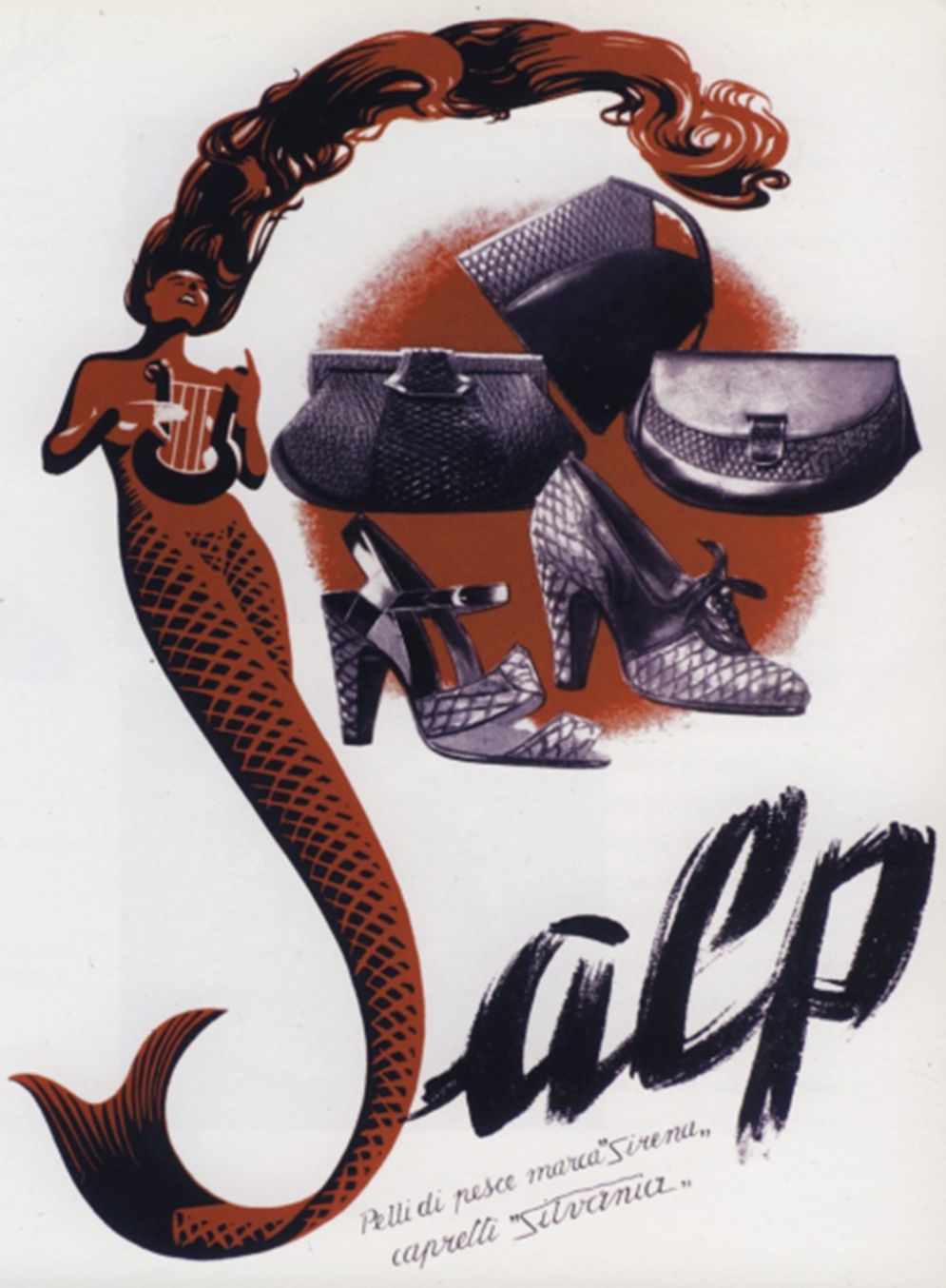

Apart from Ferragamo's brilliance, which was an exceptional example of Italian “making a virtue of scarcity”, the Thirties were very important for the experimentation of new materials and shape in handmade shoemaking. Since 1935, and especially during the war, experiments on shark, sea bream and centrophorus skin offered interesting and economic solutions to shoemakers (Ricci, 2005) (Fig. 2). Sardinian cork, pressed, curved and glued, became a basic material for heels and soles. But also vegetable fibres and straw became part of luxury shoe production. Uppers were worked with crochet, by loom or hand-plaited, which received great acclaim, especially for seaside or cruise shoes (Ricci, 2005). Thayaht also worked on seaside shoes creating prototypes for comfortable but at the same time sought-after footwear called “Florence sandals” and “Forte dei Marmi sandals”, a seaside resort frequented by artists of the time (Toto, 2014).

In the summer of 1939, due to restriction of materials in view of the looming war, Italian fashion magazines recommended sandals with the high sole of cork or twine with an orthopaedic heel which “although not the epitome of beauty is very comfortable and less tiring than wearing sandals without heels or clogs with wooden heels”, while for less wealthy women, designs and patterns were published showing how to make their own string shoes (Domani sarà di moda, 1939).

Again in Florence, in the field of women's accessories, la maison Gucci was born, another important Italian fashion name, founded in 1921 by Guccio Gucci (Pinchera 2009; Gucci, 2006). Son of a straw-maker, Guccio Gucci first worked in Paris and then London as a liftboy at the Savoy Hotel: this experience gave him his refined taste for travel accessories used by the English nobility Returning to Florence after an apprenticeship with the Franzi company, Gucci opened a shop selling travel goods imported from Germany and a laboratory where he produced horse riding leather accessories, from which came the house emblem of bridle and stirrups Pinchera (2013, pp 13–16). His success led him to open a custom manufacturing plant in Florence in the Thirties, bolstering his activities and extending production to women's bags and cases Gucci also received international recognition during the years of autarchy when the lack of leathers obliged the Florentine craftsman to search for “alternative” materials, triggering the originality of the designer label with jute, hemp and bamboo, which in 1947 he used for the handle of the famous woman's bamboo bag His success was enhanced by opening a shop in Via Condotti, Rome in 1938 In the following years, Gucci opened shops all over the world and continued to update his products through continual research for innovative materials never before used for women's bags, cases and small leather goods, like the duffle bag called GG canvas because of its printed ornamental double G, the logo of the Maison.

6ConclusionsThe inter-war years were a fundamentally important period for Italian fashion. The birth of capital intensive endeavours, like that of artificial fibres, indispensable for the textile industry, intertwined with small and medium craftsmen enterprises which provided new materials for constructive experimentation and innovation. Crafts and fashion houses showed how the inherent standard of the Italian highest quality expression was – and would be in the future – its particular vocation in coupling creativity and technology, innovation and research for the elegant and well made, resulting in an excellent product recognised internationally. In particular the autarkic climate of the Thirties, the search for an Italian style and a national identity under the fascist regime, which concentrated its interest on fashion, effected the revitalisation of Italian stylists, the use of national raw materials, and the creation of products able to uphold the new political, social and economic image. In those years, artisans and fashion put themselves at the service of a Utopia which art, particularly the futuristic movement, supported and coloured, contributing to reinforce a national cultural climate. The futurists anticipated the figure of industrial designers of the Fifties, giving a fundamental contribution to the birth and international success of the Made in Italy industry, not only in fashion.

However, the first basic steps in creating an Italian style did not occur in women's fashion but in men's. Even if the regime, by setting up the Ente Nazionale della Moda “coordination and positioning of various productive specialities” (Autarchia, 1941, p. 31) attempted to free Italian style from Paris, and many fashion houses tried to create their own style, a style capable of competing with the French did not succeed.

Italian male sartorial demonstrated it was more receptive towards improvements in the technique of constructing a garment linked to the cut and body measurement and showed itself more receptive towards solutions to improve the comfort of men's clothing (Davanzo Poli, 2003, p. 552). During the 20 years of fascism this inclination towards technical improvement was joined by a desire to free men's fashion from English supremacy, offering a less rigid and more comfortable style, revolutionising the most important male garment: the jacket. But it was in women's accessories and shoes that the taste, creativity and inventiveness of fashion designers showed innovative capacity, and launched the first successful brands of Made in Italy like Ferragamo and Gucci.

Mariano Fortuny, of Spanish origin (Granada 1871 – Venice 1949), in 1873 moved with his family to Rome, where his father, Mariano Fortuny y Marsal, a successful painter, opened an atelier. When his father died in 1874, he was hosted in Paris by a paternal uncle, a fashionable portrait painter, who introduced him to painting. At age 18, he returned to Italy and settled permanently in Venice but continued to travel regularly to Paris. It was in Venice, with its artistic heritage, combined with the age-old traditions of decorators, weavers and goldsmiths, where Fortuny found a rich and steady source of creative inspiration. In Venice, in the district of Giudecca, in 1919 he founded a factory for the industrial production of its fabrics in cotton, opening boutiques in major European capitals (Di Castro, 1997).

For example, in 1924 the magazine La Rivista Illustrata del Popolo d’Italia published an article on a fashion show at The Fashion Walk of Spring in Boston (Orlandini, 1924).

Conquiste dell’abbigliamento italiano. Il Piccolo, 1938 June 16. In: Bollettino di Informazioni dell’Ente Nazionale della Moda. (12), 1938 July. (Grandi and Vaccari, 2004, p. 211).