One of the main features of the relationship between health professionals and their patients is that their effects can be measured. To do this, we need instruments that are well built and that have proven their validity and reliability empirically and experimentally. The objective of this study is to analyse the psychometric properties of the Health Professionals Communication Skills Scale (HP-CSS), which evaluates the communication skills that health professionals use to relate to their patients. The sample consisted of 410 health professionals in the region of Murcia, Spain, and 517 in the province of Alicante, Spain. We obtained descriptive statistics and discrimination indices of the items, the internal structure of the scale using both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, the internal consistency, the temporal stability, and the external evidence of validity. The results indicate that the HP-CSS is a valid and reliable instrument and is also useful for the purpose and context in which it will be used.

Una de las principales características de la relación que se produce entre los diferentes profesionales de la salud y los pacientes es que sus efectos pueden ser medidos. Para ello precisamos de instrumentos que estén bien construidos y que demuestren, de forma empírica y experimental, su validez y fiabilidad. El objetivo de este trabajo es analizar las propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Habilidades de Comunicación de Profesionales de la Salud (EHC-PS) que evalúa las habilidades de comunicación que los profesionales de la salud tienen al relacionarse con sus pacientes. La muestra estuvo compuesta por 410 profesionales de la salud de la Región de Murcia (España) y 517 de la Provincia de Alicante (España). Se obtuvieron los estadísticos descriptivos y los índices de discriminación de los ítems, la estructura interna de la escala mediante Análisis Factorial Exploratorio y Confirmatorio, la consistencia interna, la estabilidad temporal y evidencias externas de validez. Los resultados obtenidos indican que la EHC-PS resulta ser un instrumento válido y fiable y, además, útil para el propósito y el contexto en que va a ser utilizado.

In recent decades the model of the relationship between health professionals and the patient has undergone a profound transformation. Healthcare organizations have in recent years experienced a significant change, having gone from being service-providing entities oriented by professionals to following user-centred organizational models and being preoccupied with meeting their expectations (Epstein & Street, 2011; Scholl, Zill, Härter, & Dirmaier, 2014). Today, Western societies have advanced towards democratic social relations directed by the idea of free and informed consent of the citizens. The current customer orientation of public services is the result of this change in mindset. Thus, patients are acquiring a progressively more active role, being more conscious of their rights and responsibilities, which are protected by law, such as the Law on Patient Autonomy (2002), and promoted by international agencies such as the World Health Organization (World Health Organization, 1993).

Empirical and experimental research conducted in different contexts on the relational aspects between health professionals and patients have shown greater satisfaction of both the clinician and the patient, cost containment, adherence to treatment, professional burnout prevention, prevention of medical-legal problems, improvement of quality-of-care indicators, and improvement in health outcomes (Barth & Lannen, 2011; Beach et al., 2005; Bernard, de Roten, Despland, & Stiefel, 2012; Bragard et al., 2010; Capone, 2014; Cebrià, Palma, Segura, Gracia, & Pérez, 2006; Lenzi, Baile, Costantini, Grassi, & Parker, 2011; Rezaei & Askari, 2014; Rider, 2010; Scholl et al., 2014; Stiefel et al., 2010; Uitterhoeve, Bensing, Grol, Demulder, & Van Achterberg, 2010; Vargas, Cañadas, Aguayo, Fernández, & de la Fuente, 2014; Xinchun et al., 2014).

Therefore, when communication is established between the health professional and the patient, it focuses on the needs and perspectives of the latter and presents a number of characteristics and properties that can convert it into a therapeutic instrument (Mead & Bower, 2002). One of the principal features of the clinical relationship that is produced between different health professionals and patients is that their effects can be measured. We need instruments for these measurements that are well constructed and whose psychometric properties can be demonstrated empirically and experimentally, while being feasible to use in practice (Peterson, Calhoun, & Rider, 2014).

The absence of instruments that measure this construct led us to build the Health Professionals Communication Skills Scale (HP-CSS). This paper presents the continuation of the study that created the scale (Leal, Tirado, Rodríguez-Marín, & van-der Hofstadt, in press), which details all aspects relating to the semantic and syntactic definition of the construct, the assessment by the experts of the definition, the process of creating the items presented in tables of the specification of the scale and items, the assessment thereof by the experts, and the pilot study. The aim of this paper is to analyse the psychometric properties of the Health Professionals Communication Skills Scale (HP-CSS) [Escala sobre Habilidades de Comunicación de Profesionales de la Salud (EHC-PS) in Spanish]. To achieve this objective, the psychometric properties of the scale in a first sample were analysed: item analysis, analysis of the internal structure through exploratory factor analysis (EFA), reliability analysis, and external evidence of validity. In a second sample, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to confirm the stability of the internal structure of the scale in a different sample of another health system.

MethodParticipantsThe first sample, in the region of Murcia, Spain, was used to analyse the psychometric properties of the scale. It was composed of a total of 410 health professionals, obtained by quota sampling of the following hospitals: Virgin of the Arrixaca University General Hospital, Queen Sofia University General Hospital, Los Arcos del Mar Menor Hospital, and the Molina Hospital. This sample comprised 94 physicians (23%), 176 nurses (43%), and 140 nursing assistants (34%), of whom 278 (67,8%) were women and 132 (32,2%) were men. The second sample, collected in the province of Alicante, was used to perform the CFA. It was composed of a total of 517 participants, obtained by quota sampling of the Alicante University General Hospital, Vega Baja Regional, and Torrevieja. The last one was a privately run public centre. This sample comprised 103 physicians (20%), 274 nurses (53%), and 140 nurses (27%), of whom 374 (72,3%) were women and 143 (27,7%) were men. As inclusion criteria, all participants had to 1) be of legal age, 2) perform their healthcare work in the field of primary care or specialized care, 3) be a doctor, nurse, or nursing assistant, and 4) sign the informed consent.

Instruments- -

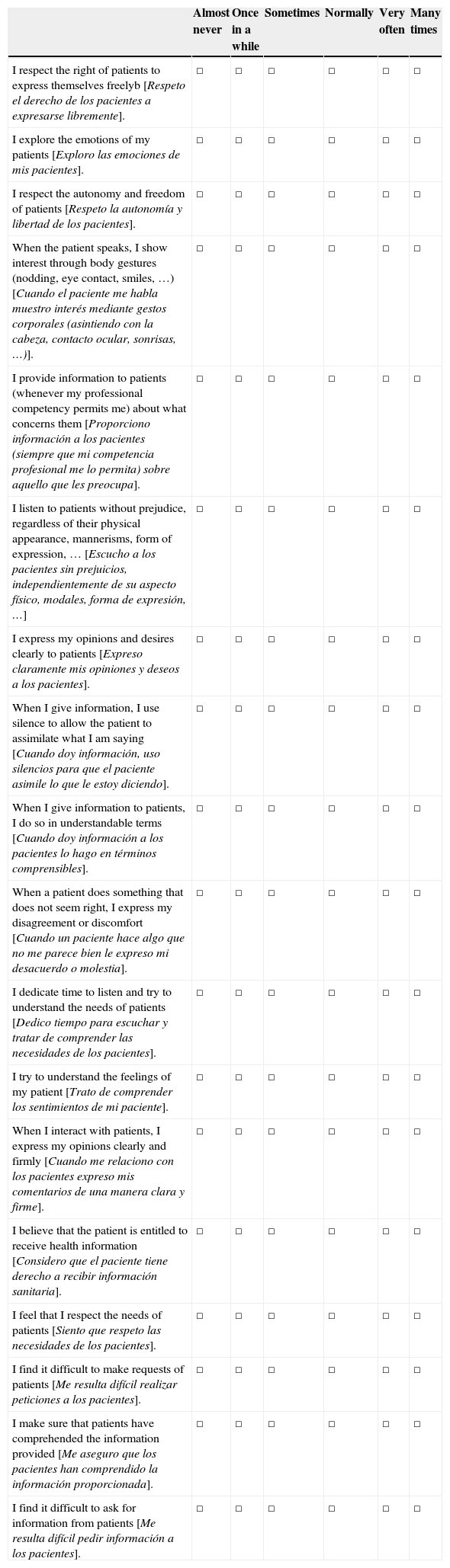

Health Professionals Communication Skills Scale (HP-CSS). Instrument validation object, composed of 42 items, half being worded inversely. The scale of response was graded into six alternatives with linguistic quantifiers of frequency: 1=almost never, 2=once in a while, 3=sometimes, 4=normally, 5=very often and 6=many times, established on the basis of the work of Cañadas and Sánchez-Bruno (1998), and Cañadas and Tirado (2002) concerning response categories in Likert-type scales. It included four dimensions: a) Informative Communication, consisting of 12 items (3, 6, 11, 13, 16, 18, 20, 27, 30, 38, 39 and 42) that reflected the manner by which the health professionals obtain and provide information in the clinical relationship that they establish with the patients; b) Empathy, composed of 13 items (4, 5, 12, 14, 17, 21, 22, 23, 28, 29, 36, 37 and 41) that reflected the capacity of the health professionals to comprehend the feelings of the patients and make their empathy evident in the relationship, as well as the behavioural dimension, the empathic attitude, composed of active listening and empathic response; c) Respect and Authenticity, with 5 items (2, 10, 26, 33 and 34) that evaluated the respect and authenticity, or congruence, that is shown by the health professionals in the clinical relationship they establish with patients; and d) Social Skill, with 12 items (1, 7, 8, 9, 15, 19, 24, 25, 31, 32, 35 and 40) that reflected the ability of the health professionals to be assertive or to exhibit socially skilful behaviours in the clinical relationship they establish with patients. Appendix 1.

- -

Social Skills Scale (SSS; Escala de Habilidades Sociales (EHS) in Spanish; Gismero, 2010). In its definitive version, this scale is composed of 33 items with four alternative answers, of which 28 are worded in an inverse sense and 5 worded in a positive sense. It consists of six factors: I) Self-expression in social situations (8 items); II) Defence of one's rights as a consumer (5 items); III) Expression of anger or disagreement (4 items); IV) Saying no and cutting off interactions (6 items); V) Making requests (5 items); and VI) Initiating positive interactions with the opposite sex (5 items). It is a brief, specific instrument that was built, validated, and typified for a Spanish population and with adequate psychometric properties.

- -

Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS; Gil-Monte, 2005), in its version adapted to the Spanish population. It is mostly used to assess the frequency and intensity of burnout syndrome for healthcare workers. It consists of 22 items, with three subscales that measure the three dimensions that make up the syndrome: a) Emotional exhaustion (EE), with nine items that describe feelings of being overwhelmed and emotionally exhausted by work; b) Depersonalization (DP), with five items that describe an impersonal response and lack of feelings towards people receiving attention or service; c) Personal accomplishment at work (PA), with eight items that describe feelings of competence and successful achievement in working towards others. These 22 items are measured using a Likert-type frequency scale with seven categories ranging from never (0) to every day (6). The internal consistency (Cronbach's α) was satisfactory for the dimensions of emotional exhaustion (α=0,85) and personal accomplishment at work (α=0,71), and moderate for the depersonalization dimension (α=0,58). The structure of three oblique factors presented a good fit.

To carry out the study, permission of the respective management of the centres and the approval of the ethics committee was obtained. The principal bioethical aspects were settled by ensuring voluntary and informed participation and the confidentiality of the data and information of the study participants. The sample from Murcia was collected from September to December 2011 by students of the School of Nursing at the Catholic University of Murcia and by supervisors/coordinators of selected nursing centres. They recruited health professionals who voluntarily participated in the project without receiving any incentive. After 40 days, all of the professionals completed the scale again. This sample was used to analyse the psychometric properties of the initial version of the scale. In Alicante, the sample was collected from February to April 2012 by nursing supervisors/coordinators in the same way as above and was used to perform the CFA of the final solution obtained in the EFA.

Data analysisA descriptive analysis of the items (mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis) was performed. The item discrimination was calculated with the corrected item-total dimension correlation (Carretero-Dios & Pérez, 2005). The EFA and CFA were used to analyse the extent to which the items and components of the scale conformed to the construct established in the semantic definition (Elosua, 2003). As recommended by numerous studies (Ferrando & Anguiano-Carrasco, 2010; Lloret-Segura, Ferreres-Traver, Hernández-Baeza, & Tomás-Marco, 2014; Schmitt, 2011), we considered the EFA and CFA as the two poles of a continuum, i.e., the EFA imposes minimal restrictions to obtain a factorial solution according to the exposed theory (semantic and syntactic definition), which can be transformed by applying different criteria, and the CFA imposes much stronger restrictions that test the final factor solution. Because the items met the assumptions of multivariate normality, the maximum likelihood (ML) method was used (Byrne, 2013). A combination of fit indices were used to evaluate the model fit: χ2/gl, Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). In general, values less than 3 for χ2/gl; greater than .90 for IFI, TLI and CFI; less than or equal to .06 for the RMSEA; and less than or equal to .08 for the SRMR were considered indicative of good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

For the cleaning of the items, the descriptive statistics of the items, discrimination indices, and factor loadings were used, following the recommendations for the selection of the items (Lloret-Segura et al., 2014) because the semantic content of the dimension would be represented by the final items. The reliability was analysed as internal consistency with Cronbach's α for the dimensions of the scale (Carretero-Dios & Pérez, 2007; Cortina, 1993). The temporal stability of the scores of the items was evaluated with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), interpreted according to the classification established by Landis and Koch (1977). The search for external evidence of validity was based on a) correlations between the scores for each dimension of the HP-CSS with the scores for each dimension and the total of the SSS and should correlate positively; b) correlations of the dimensions of the HP-CSS with the EE, DP, and PA dimensions of the MBI. We hypothesized that HP-CSS would show a negative relationship with EE and DP and a positive relationship with PA. These hypotheses were established in the syntactic definition of the construct (Leal et al., in press). The IBM® SPSS® Statistics 20.0 statistical package with the Amos™ algorithm was used.

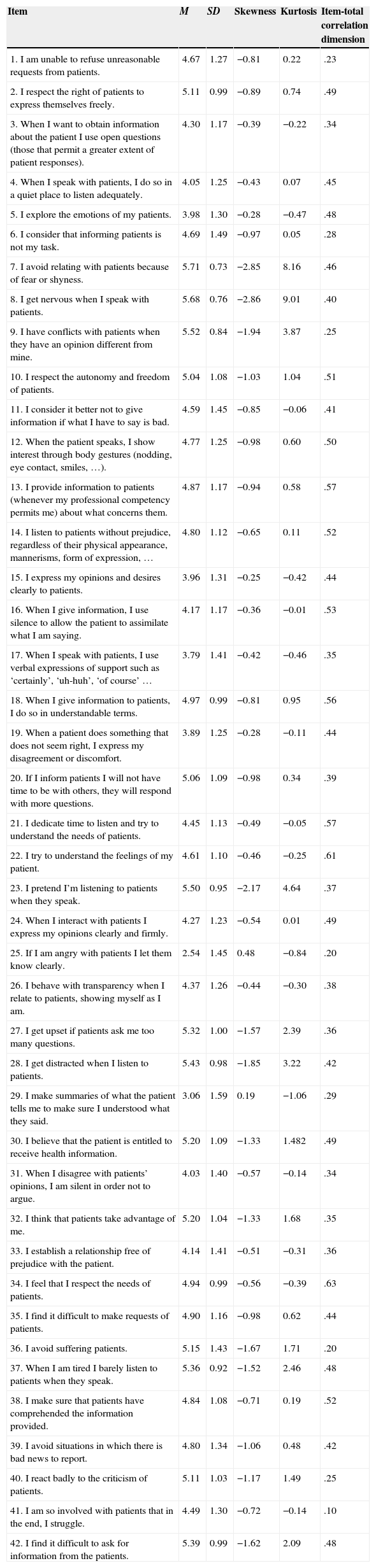

ResultsItem analysisDescriptive statistics of the items (mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis) and discrimination indices, which were greater than .25–.30 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1995) in 90% of cases, were obtained (Table 1).

Descriptive statistics and item-total correlation dimension.

| Item | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Item-total correlation dimension |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I am unable to refuse unreasonable requests from patients. | 4.67 | 1.27 | −0.81 | 0.22 | .23 |

| 2. I respect the right of patients to express themselves freely. | 5.11 | 0.99 | −0.89 | 0.74 | .49 |

| 3. When I want to obtain information about the patient I use open questions (those that permit a greater extent of patient responses). | 4.30 | 1.17 | −0.39 | −0.22 | .34 |

| 4. When I speak with patients, I do so in a quiet place to listen adequately. | 4.05 | 1.25 | −0.43 | 0.07 | .45 |

| 5. I explore the emotions of my patients. | 3.98 | 1.30 | −0.28 | −0.47 | .48 |

| 6. I consider that informing patients is not my task. | 4.69 | 1.49 | −0.97 | 0.05 | .28 |

| 7. I avoid relating with patients because of fear or shyness. | 5.71 | 0.73 | −2.85 | 8.16 | .46 |

| 8. I get nervous when I speak with patients. | 5.68 | 0.76 | −2.86 | 9.01 | .40 |

| 9. I have conflicts with patients when they have an opinion different from mine. | 5.52 | 0.84 | −1.94 | 3.87 | .25 |

| 10. I respect the autonomy and freedom of patients. | 5.04 | 1.08 | −1.03 | 1.04 | .51 |

| 11. I consider it better not to give information if what I have to say is bad. | 4.59 | 1.45 | −0.85 | −0.06 | .41 |

| 12. When the patient speaks, I show interest through body gestures (nodding, eye contact, smiles, …). | 4.77 | 1.25 | −0.98 | 0.60 | .50 |

| 13. I provide information to patients (whenever my professional competency permits me) about what concerns them. | 4.87 | 1.17 | −0.94 | 0.58 | .57 |

| 14. I listen to patients without prejudice, regardless of their physical appearance, mannerisms, form of expression, … | 4.80 | 1.12 | −0.65 | 0.11 | .52 |

| 15. I express my opinions and desires clearly to patients. | 3.96 | 1.31 | −0.25 | −0.42 | .44 |

| 16. When I give information, I use silence to allow the patient to assimilate what I am saying. | 4.17 | 1.17 | −0.36 | −0.01 | .53 |

| 17. When I speak with patients, I use verbal expressions of support such as ‘certainly’, ‘uh-huh’, ‘of course’ … | 3.79 | 1.41 | −0.42 | −0.46 | .35 |

| 18. When I give information to patients, I do so in understandable terms. | 4.97 | 0.99 | −0.81 | 0.95 | .56 |

| 19. When a patient does something that does not seem right, I express my disagreement or discomfort. | 3.89 | 1.25 | −0.28 | −0.11 | .44 |

| 20. If I inform patients I will not have time to be with others, they will respond with more questions. | 5.06 | 1.09 | −0.98 | 0.34 | .39 |

| 21. I dedicate time to listen and try to understand the needs of patients. | 4.45 | 1.13 | −0.49 | −0.05 | .57 |

| 22. I try to understand the feelings of my patient. | 4.61 | 1.10 | −0.46 | −0.25 | .61 |

| 23. I pretend I’m listening to patients when they speak. | 5.50 | 0.95 | −2.17 | 4.64 | .37 |

| 24. When I interact with patients I express my opinions clearly and firmly. | 4.27 | 1.23 | −0.54 | 0.01 | .49 |

| 25. If I am angry with patients I let them know clearly. | 2.54 | 1.45 | 0.48 | −0.84 | .20 |

| 26. I behave with transparency when I relate to patients, showing myself as I am. | 4.37 | 1.26 | −0.44 | −0.30 | .38 |

| 27. I get upset if patients ask me too many questions. | 5.32 | 1.00 | −1.57 | 2.39 | .36 |

| 28. I get distracted when I listen to patients. | 5.43 | 0.98 | −1.85 | 3.22 | .42 |

| 29. I make summaries of what the patient tells me to make sure I understood what they said. | 3.06 | 1.59 | 0.19 | −1.06 | .29 |

| 30. I believe that the patient is entitled to receive health information. | 5.20 | 1.09 | −1.33 | 1.482 | .49 |

| 31. When I disagree with patients’ opinions, I am silent in order not to argue. | 4.03 | 1.40 | −0.57 | −0.14 | .34 |

| 32. I think that patients take advantage of me. | 5.20 | 1.04 | −1.33 | 1.68 | .35 |

| 33. I establish a relationship free of prejudice with the patient. | 4.14 | 1.41 | −0.51 | −0.31 | .36 |

| 34. I feel that I respect the needs of patients. | 4.94 | 0.99 | −0.56 | −0.39 | .63 |

| 35. I find it difficult to make requests of patients. | 4.90 | 1.16 | −0.98 | 0.62 | .44 |

| 36. I avoid suffering patients. | 5.15 | 1.43 | −1.67 | 1.71 | .20 |

| 37. When I am tired I barely listen to patients when they speak. | 5.36 | 0.92 | −1.52 | 2.46 | .48 |

| 38. I make sure that patients have comprehended the information provided. | 4.84 | 1.08 | −0.71 | 0.19 | .52 |

| 39. I avoid situations in which there is bad news to report. | 4.80 | 1.34 | −1.06 | 0.48 | .42 |

| 40. I react badly to the criticism of patients. | 5.11 | 1.03 | −1.17 | 1.49 | .25 |

| 41. I am so involved with patients that in the end, I struggle. | 4.49 | 1.30 | −0.72 | −0.14 | .10 |

| 42. I find it difficult to ask for information from the patients. | 5.39 | 0.99 | −1.62 | 2.09 | .48 |

Note. M: Mean; SD: Standard deviation

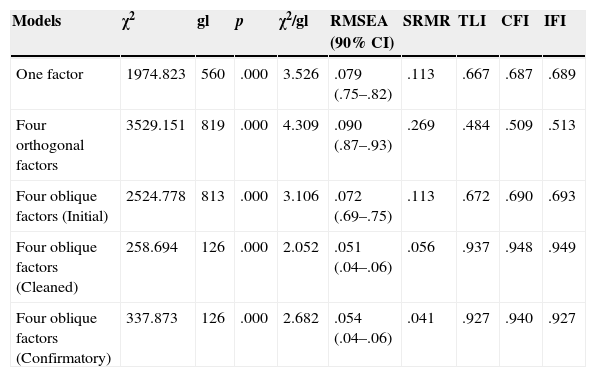

An EFA with ML was performed using structural equation models (Mardia's coefficient=332.64). Three theoretical models were tested: a one-factor model, a four-orthogonal-factor model, and a four-oblique-factor model. All of the models had an insufficient fit that needed to be improved (Table 2).

Goodness of fit indices of the one-factor model, four-orthogonal-factor model, and four-oblique-factor model.

| Models | χ2 | gl | p | χ2/gl | RMSEA (90% CI) | SRMR | TLI | CFI | IFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One factor | 1974.823 | 560 | .000 | 3.526 | .079 (.75–.82) | .113 | .667 | .687 | .689 |

| Four orthogonal factors | 3529.151 | 819 | .000 | 4.309 | .090 (.87–.93) | .269 | .484 | .509 | .513 |

| Four oblique factors (Initial) | 2524.778 | 813 | .000 | 3.106 | .072 (.69–.75) | .113 | .672 | .690 | .693 |

| Four oblique factors (Cleaned) | 258.694 | 126 | .000 | 2.052 | .051 (.04–.06) | .056 | .937 | .948 | .949 |

| Four oblique factors (Confirmatory) | 337.873 | 126 | .000 | 2.682 | .054 (.04–.06) | .041 | .927 | .940 | .927 |

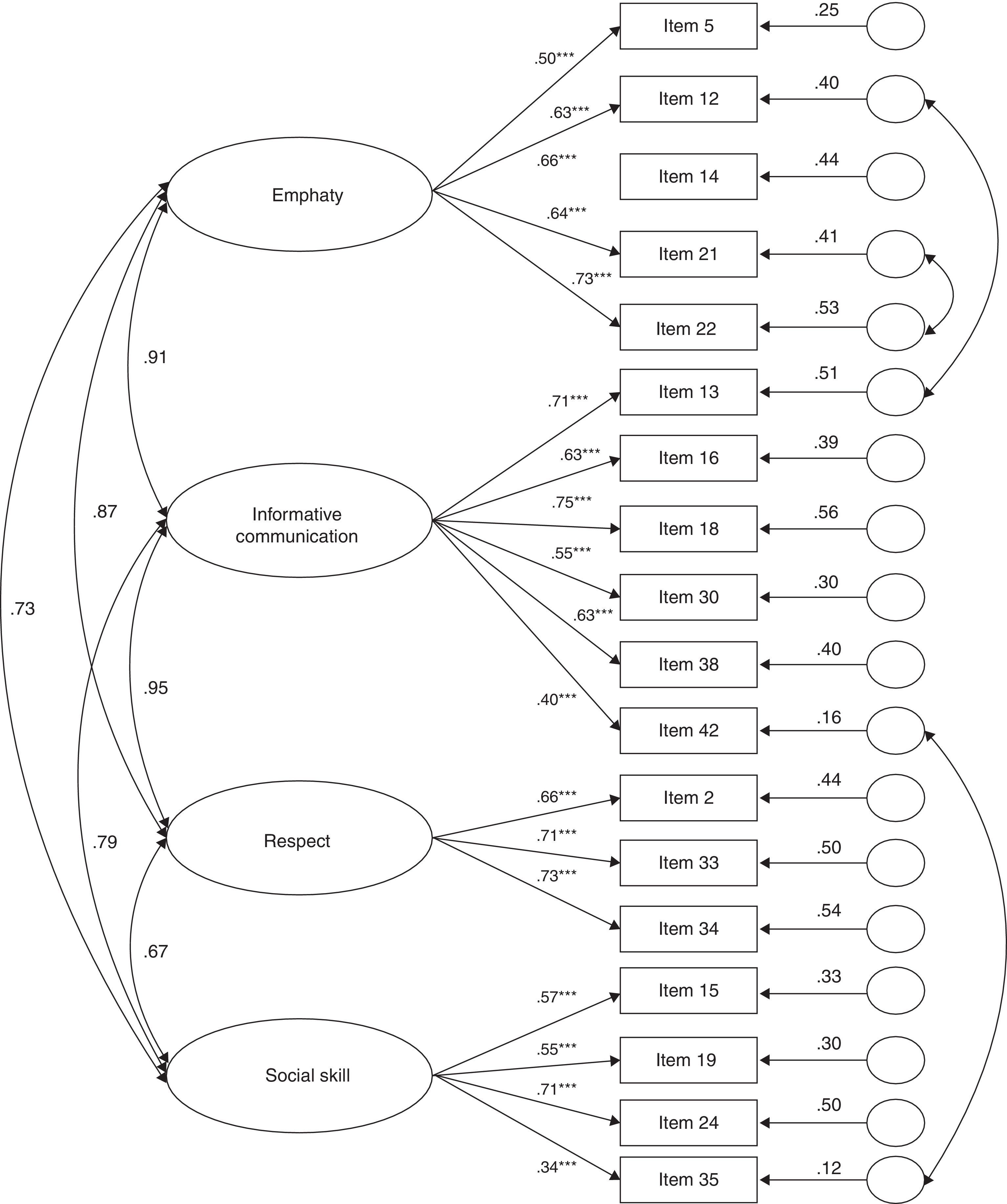

The correction and respecification focused on the oblique factor model, in accordance with the theory underlying the semantic and syntactic definition of the construct. Through an iterative cleaning process in accordance with the item loadings and the model fit, items were eliminated: 4, 17, 23, 28, 29, 36, 37, and 41 of Empathy; 3, 6, 11, 20, 27, and 39 of Information Communication; 26 and 33 of Respect and Authenticity; and 1, 7, 8, 9, 25, 31, 32, and 40 of Social Skill. The final scale was made up of 18 items. The modification indices indicated the relevance of the correlated errors of items 12 and 13, 21 and 22, and 35 and 42. Because their content was similar, modifications were made. The EFA revealed that all items of the corrected oblique factor model had factor loadings above .40, except item 35 of the Social Skill dimension (Figure 1). The indices indicated a good fit (Table 2).

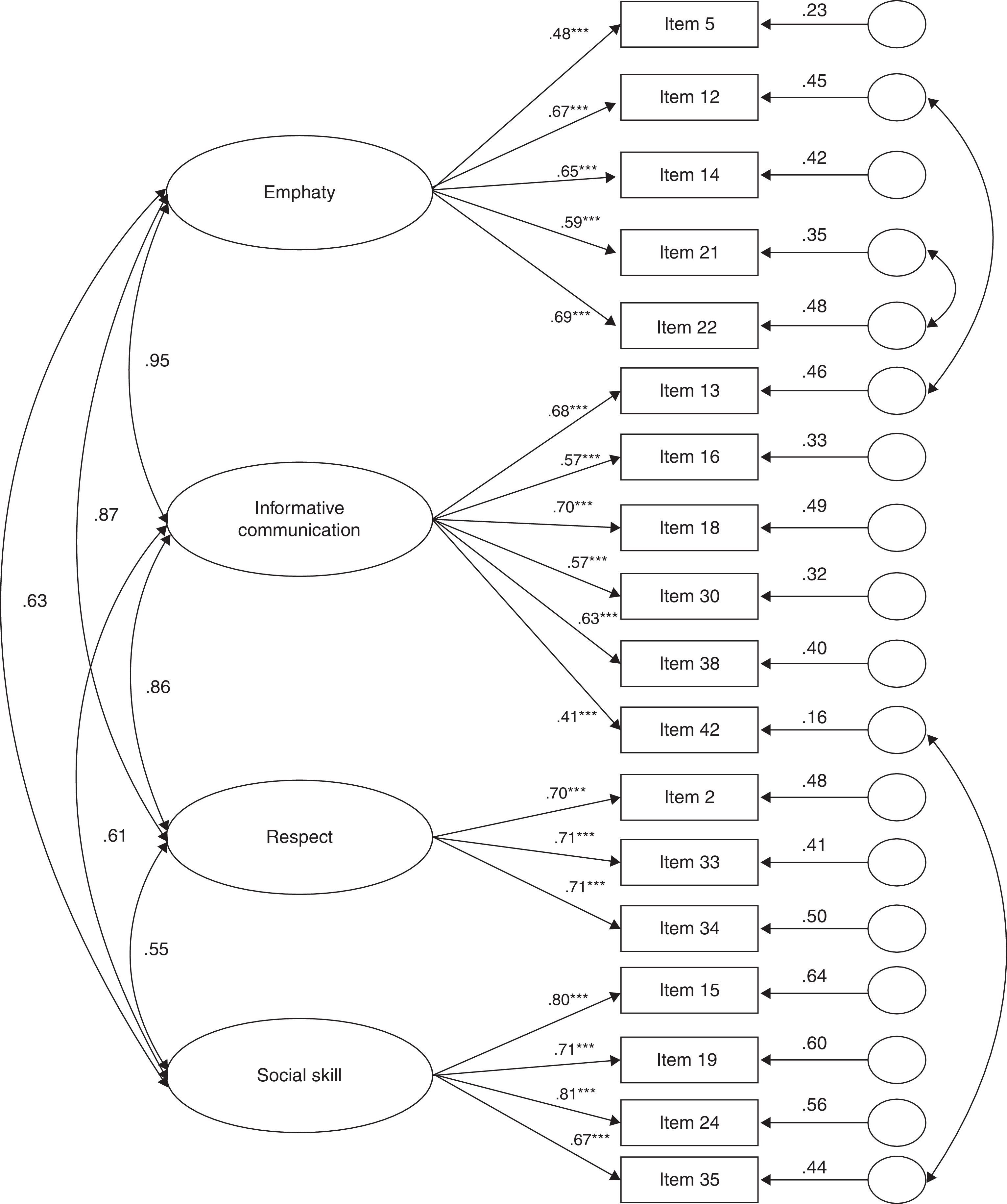

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)The obtained four-oblique-factor model was tested (ML; Mardia's coefficient=82.80). All of the items reached factor loadings greater than .40 (Figure 2). The indices showed a good fit (Table 2).

Reliability AnalysisThe internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of HP-CSS was .77 for Empathy, .78 for Informative Communication, .74 for Respect, and .65 for Social Skill.

The ICC showed a high correlation between the test and re-test scores: Empathy=.87 (p<.000) 95% CI (.85–.88); Informative Communication=.88 (p<.000) 95% CI (.86–.89); Respect=.82 (p<.000) 95% CI (.79–.84); and Social Skill=.84 (p<.000) 95% CI (.81–.86).

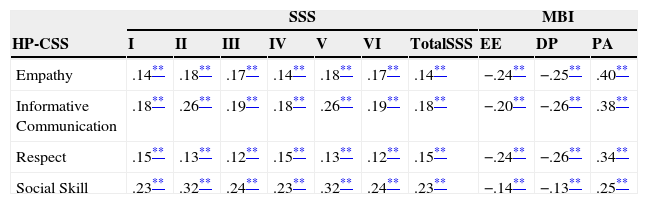

Evidence of validityThe analysis of the correlations between the dimensions of the HP-CSS and the dimensions and the total of the SSS, as expected, were statistically significant (p<.01), although somewhat lower than expected (Table 3). The correlations with the dimensions of the MBI were negative and statistically significant (p<.01) for EE and DP and positive and statistically significant (p<.01) for PA (Table 3).

Bivariate correlations between the dimensions of the HP-CSS and the dimensions of the SSS and the MBI.

| SSS | MBI | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP-CSS | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | TotalSSS | EE | DP | PA |

| Empathy | .14** | .18** | .17** | .14** | .18** | .17** | .14** | −.24** | −.25** | .40** |

| Informative Communication | .18** | .26** | .19** | .18** | .26** | .19** | .18** | −.20** | −.26** | .38** |

| Respect | .15** | .13** | .12** | .15** | .13** | .12** | .15** | −.24** | −.26** | .34** |

| Social Skill | .23** | .32** | .24** | .23** | .32** | .24** | .23** | −.14** | −.13** | .25** |

Note. SSS=Social Skills Scale. I=Self-expression in social situations; II=Defence of one's rights as a consumer; III=Expression of anger or disagreement; IV=Saying no and cutting off interactions; V=Making requests; VI=Initiating positive interactions with the opposite sex. MBI=Maslach Burnout Inventory. HP-CSS=Health Professionals Communication Skills Scale. EE=Emotional exhaustion; DP=Depersonalization; PA=Personal accomplishment at work.

In this study, we evaluated HP-CSS and analysed its psychometric properties in two heterogeneous samples composed of the three types of health professionals that are most numerous in our health system (nursing assistants, nurses, and physicians).

In reference to discrimination indices, as Carretero-Dios and Pérez (2005) noted, when a scale is composed of dimensions or sub-constructs, the discrimination calculations must be performed by facet or dimension. Thus, the corrected item-total dimension correlations, which were greater than .25–.30 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1995), except in items 29, 36, and 41 of Empathy, in item 6 of Informative Communication and in items 1, 9, 25, and 40 of Social Skill, were analysed. Most of the items showed appropriate behaviour in terms of their discrimination with the total score of the dimension to which they belonged. Therefore, we can affirm that proper relationships between the items and the total of the points obtained in the dimension were found. In this sense, it should be noted that the higher these correlations for all items in one dimension are, the greater the reliability of this component calculated through internal consistency will be. Therefore, when the item discrimination is analysed, the calculation of the reliability of that component through Cronbach's α is usually included. However, in this paper, the reliability analysis was performed after the internal structure of the scale was analysed and the final grouping of items was obtained (Carretero-Dios & Pérez, 2007).

Regarding the analysis of the internal structure of the scale, following the recommendations of Lloret-Segura et al. (2014), an EFA of the full model was performed, including all items. Then, the scale was improved by eliminating elements according to various psychometric and semantic criteria of each item. In addition, several models were proposed to analyse the comparative fit between the items (Table 2), and the relationships that were expected were clearly specified. The model that best fit the indices was the one with four oblique factors. Therefore, for the respecification of the model, and considering the semantic definition of the construct (Leal et al., in press), it was the only model analysed. Once the items were eliminated, as noted by Nunnally and Bernstein (1995), referring specifically to attitude scales, the scale was reduced to 18 items in the definitive instrument (see Appendix 1). Thus, in the corrected model proposed, all items had factor loadings greater than .40 except for item 35 of Social Skill, which we decided to retain because it contributed more semantic information, and the goodness of fit indices were adequate for retention. It is important to note that after eliminating items 26 and 33 of the Respect and Authenticity dimension, the remaining items in this dimension (2, 10, and 34) only referred to respect, so this dimension was renamed Respect.

Once the internal structure of the scale was delimited in the EFA with the definitive items, a content analysis was performed so that the final items adequately represented the dimensions proposed in the semantic definition of the construct, confirming that they adequately represented the content of the proposed dimensions. To verify that the internal structure of the scale was stable, as recommended by some authors (Carretero-Dios & Pérez, 2005; Elosua, 2003), a CFA was performed on a different sample of health professionals, from another health system. Here again, we obtained a good model fit.

The reliability analysis of the scale scores, as mentioned above, was performed with the final scale and not with experimental forms (Carretero-Dios & Pérez, 2007). Thus, the internal consistency was greater than .70 in all of the dimensions except for the Social Skill dimension (.65), although the value was very close and can be considered appropriate if the purpose of the scale is research (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1995). As for the temporal stability in the scores of the items, a high concordance (Landis & Koch, 1977) was obtained in all of the dimensions, indicating a high stability of the scores of the participants in the test and in the retest.

Some time ago, a consensus was reached on the idea of validity as a unitary concept (Carretero-Dios & Pérez, 2005; Evers et al., 2013), speaking at that time about obtaining external evidence of validity. Thus, when obtaining external evidence of validity, we can observe that the expected relationships with other external constructs such as burnout and related constructs such as social skills were found, as was hypothesized in the syntactic definition of the construct (Leal et al., in press). The SSS, although it is validated for the general population (Gismero, 2010), has been used in studies to measure social skills in health professionals (Leal, Luján, Gascón, Ferrer & van-der Hofstadt, 2010; Padés & Ferrer, 2007). The results obtained empirically corroborated the fact that the health professionals consider that communication skills help make them feel safer and more competent and that they foster relationships with patients. Thus, these skills prevent, cushion, and reduce their experiences of chronic job stress and burnout, complementing previous studies (Bragard et al., 2010; Cebrià et al., 2006).

In this way, the results obtained with the HP-CSS show solutions consistent with the theory with which we started (semantic and syntactic definition), both in its composition and in the underlying structure, leading to the final form of the scale, which had some adequate psychometric properties. However, some limitations of this study should be considered. Mainly, we should continue to obtain evidence of the validity of the scale in future studies that relate the communication skills of health professionals to other external constructs.

| Almost never | Once in a while | Sometimes | Normally | Very often | Many times | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I respect the right of patients to express themselves freelyb [Respeto el derecho de los pacientes a expresarse libremente]. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I explore the emotions of my patients [Exploro las emociones de mis pacientes]. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I respect the autonomy and freedom of patients [Respeto la autonomía y libertad de los pacientes]. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| When the patient speaks, I show interest through body gestures (nodding, eye contact, smiles, …) [Cuando el paciente me habla muestro interés mediante gestos corporales (asintiendo con la cabeza, contacto ocular, sonrisas, …)]. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I provide information to patients (whenever my professional competency permits me) about what concerns them [Proporciono información a los pacientes (siempre que mi competencia profesional me lo permita) sobre aquello que les preocupa]. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I listen to patients without prejudice, regardless of their physical appearance, mannerisms, form of expression, … [Escucho a los pacientes sin prejuicios, independientemente de su aspecto físico, modales, forma de expresión, …] | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I express my opinions and desires clearly to patients [Expreso claramente mis opiniones y deseos a los pacientes]. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| When I give information, I use silence to allow the patient to assimilate what I am saying [Cuando doy información, uso silencios para que el paciente asimile lo que le estoy diciendo]. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| When I give information to patients, I do so in understandable terms [Cuando doy información a los pacientes lo hago en términos comprensibles]. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| When a patient does something that does not seem right, I express my disagreement or discomfort [Cuando un paciente hace algo que no me parece bien le expreso mi desacuerdo o molestia]. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I dedicate time to listen and try to understand the needs of patients [Dedico tiempo para escuchar y tratar de comprender las necesidades de los pacientes]. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I try to understand the feelings of my patient [Trato de comprender los sentimientos de mi paciente]. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| When I interact with patients, I express my opinions clearly and firmly [Cuando me relaciono con los pacientes expreso mis comentarios de una manera clara y firme]. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I believe that the patient is entitled to receive health information [Considero que el paciente tiene derecho a recibir información sanitaria]. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I feel that I respect the needs of patients [Siento que respeto las necesidades de los pacientes]. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I find it difficult to make requests of patients [Me resulta difícil realizar peticiones a los pacientes]. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I make sure that patients have comprehended the information provided [Me aseguro que los pacientes han comprendido la información proporcionada]. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I find it difficult to ask for information from patients [Me resulta difícil pedir información a los pacientes]. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |