There are no systematic data on the rates of antibiotic resistance after the failure of a first eradication treatment. The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of secondary resistance to antibiotics by conducting a systematic review of studies evaluating the secondary resistance of Helicobacter pylori. We identified 31 studies (2787 patients). Resistance was determined in 1764 patients. A percentage of 99.1 of patients received clarithromycin as first-line treatment and 58.7% developed resistance. A percentage of 24.3 received metronidazole and 89.7% developed resistance. Secondary resistance to amoxicillin was extremely rare. Secondary resistance after first-line treatment was very common. These findings support the recommendation not to repeat clarithromycin or metronidazole after the failure of a first eradication treatment.

No hay datos sistemáticos sobre cuáles son las tasas de resistencia a antibióticos tras el fracaso de un primer tratamiento erradicador. El objetivo del estudio es determinar la prevalencia de las resistencias secundarias a los antibióticos mediante una revisión sistemática de estudios que evaluaban las resistencias secundarias de Helicobacter pylori. Se identificaron 31 estudios (2.787 pacientes). Se determinaron resistencias en 1.764 pacientes. El 99,1% de los pacientes recibieron claritromicina como tratamiento de primera línea, y un 58,7% desarrollaron resistencias. El 24,3% de los pacientes recibieron metronidazol, desarrollando resistencias el 89,7%. La resistencia secundaria a amoxicilina fue excepcional. Las resistencias secundarias tras un primer tratamiento son muy elevadas. Estos hallazgos dan soporte a la recomendación de no repetir claritromicina o metronidazol tras el fracaso de un primer tratamiento erradicador.

Helicobacter pylori is one of the most common infections in humans. It is estimated that approximately 50% of the world's population is chronically infected by H. pylori. The infection is associated with a significant number of gastrointestinal diseases, such as peptic ulcer, chronic gastritis, functional dyspepsia, lymphoma of the lymphoid tissue associated with the gastric mucosa and gastric cancer.1,2 Since the discovery of H. pylori infection in 1982,3 multiple treatment options have been described. Until relatively recently, the standard treatment was triple therapy, which included two antibiotics (clarithromycin and amoxicillin or metronidazole) and a proton-pump inhibitor.4 However, the efficacy of this treatment has decreased, primarily because of resistance to clarithromycin and metronidazole; the rate of resistance to clarithromycin has increased to over 20% in many countries.5 In response to the poor results with triple therapy, the current guidelines have changed their recommendations to longer and more complex quadruple therapies.6–9 Although the new treatments achieve better cure rates than the triple therapy, the first-line treatment for H. pylori continues to fail in approximately 10–20% of patients.4

The majority of the consensus documents state that H. pylori resistance to antibiotics is very high after the failure of a first eradication therapy.4,9 However, that conclusion is based on a very small number of studies which analyse primary and secondary resistance together.8,10–12 To our knowledge, there are no systematic reviews which have analysed the secondary resistance rate after the failure of a first-line eradication therapy (proton-pump inhibitor, amoxicillin and clarithromycin). Having accurate figures for these resistance rates could be extremely useful for designing second- and third-line treatments.

In a recent systematic review, our group assessed the effectiveness of the second-line therapies for the eradication of H. pylori.13 The study showed that few treatments achieve cure rates of over 90%. It also showed that no individual treatment consistently obtained excellent results. A number of the studies included in our systematic review reported the resistance to antibiotics after failure of the initial treatment and made it possible to estimate secondary resistance rates for the most commonly used antibiotics.

The objective of this study is therefore to carry out a systematic evaluation to determine the prevalence of resistance to antibiotics after failure of the first-line treatment for H. pylori infection.

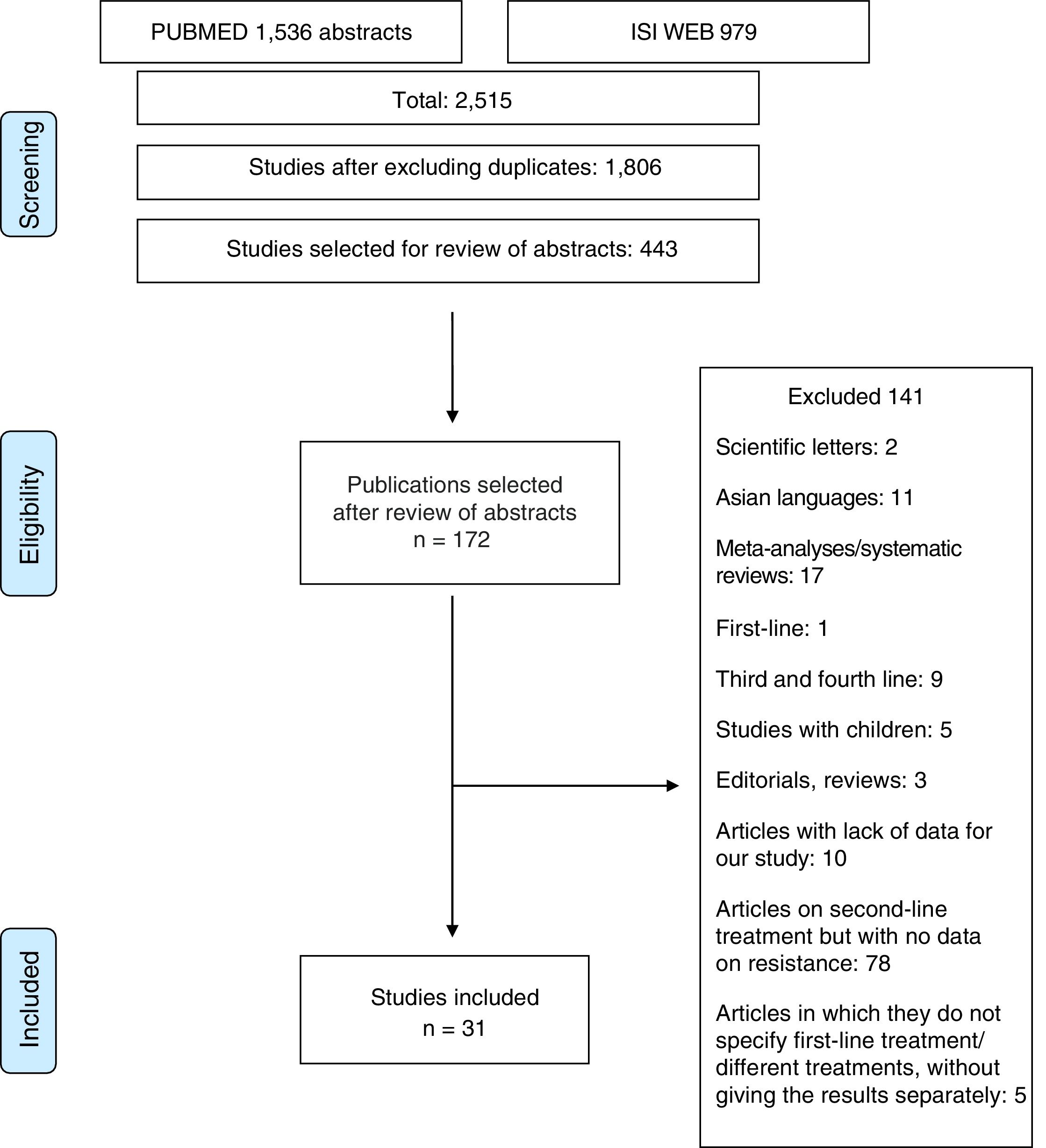

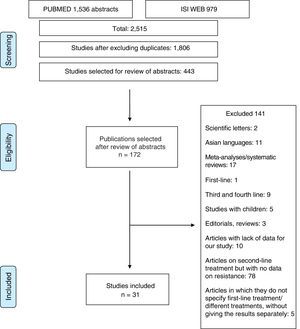

Material and methodsThe study was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA14 and MOOSE15 guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The MOOSE checklist is shown in Appendix 1 and the PRISMA flow chart in Fig. 1.

Search strategyWe carried out a systematic search of the literature limited to full-text articles published in PubMed and the Web of Science (formerly ISI Web of Knowledge) from 1996 to June 2015. The references in the selected articles, the systematic reviews and the personal databases of the authors were also reviewed. The search strategies were ((second line OR rescue OR failure) AND pylori)) in PubMed, and Title=(pylori) and Title=(second line or rescue) in the Web of Science.

Inclusion criteriaWe included published full-text articles which met the following criteria: (a) randomised or quasi-randomised clinical trials or observational studies; (b) which evaluated the rescue treatment after failure of a first treatment for H. pylori; and (c) studies that determined resistance levels. Only articles published in Spanish, Italian, French and English were included.

Exclusion criteriaThe exclusion criteria were articles in Asian languages, duplicate publications, letters to the editor, expert opinions and reviews.

Data extraction processThe data were extracted independently by two of the authors (NM and XC). The decision to include or exclude studies was made by the two authors separately. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. The level of agreement between the two authors who selected the relevant articles was above 90%. Data extraction was standardised using a data extraction table and was performed separately for each study by the two authors. In the event of disagreement, the data were reviewed and, if necessary, a consensus was arrived at. The variables compiled for this study were: year of publication; country where the study was conducted; number of patients; number of cultures and method for determining resistance and resistance rates according to the previous treatment administered; and antibiotic resistance after first-line failure.

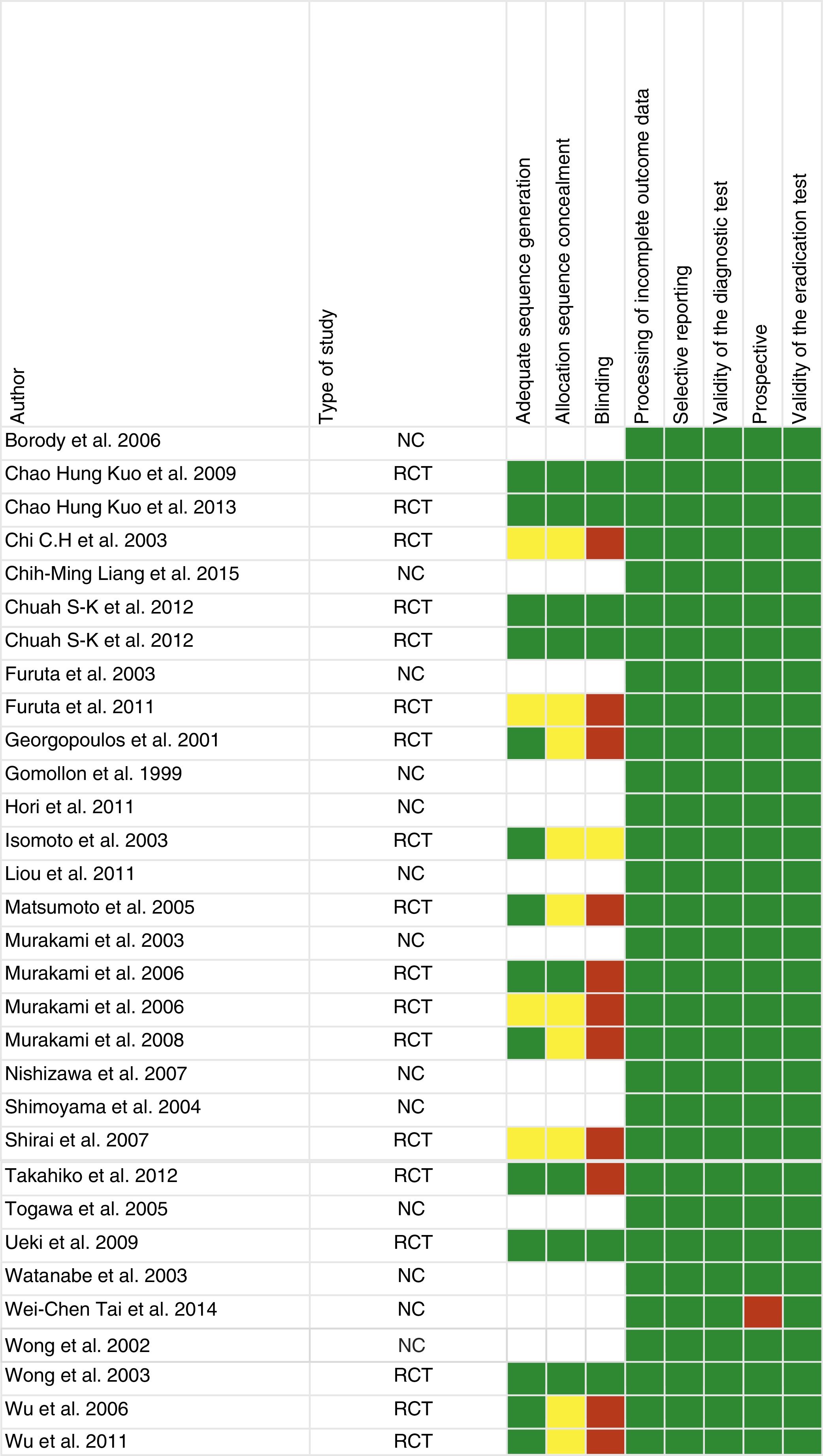

Risk of biasTwo reviewers (NM and JSD) independently assessed the risk of bias according to the current recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration for randomised clinical trials and the suggestions in the Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews for observational studies.16 Any discrepancies in the interpretation were resolved with a third reviewer (XC).

ResultsOver 2000 articles were obtained with the original search. After reviewing the abstracts, 172 full-text articles were assessed to determine their eligibility. Duplicated studies were excluded. After careful assessment, 31 articles17–47 (2787 patients) were selected which made sensitivity determinations and analysed resistance rates.

Studies excludedOne hundred and forty-one studies were finally excluded, for the following reasons: (1) studies that included paediatric patients; (2) articles that only reported results for patients in first-, third- or fourth-line treatment; (3) articles in Asian languages; (4) letters to the editor or editorials or reviews of H. pylori treatment; (5) articles in which the data provided did not allow the evaluation of study eligibility or data extraction; and (6) articles on second-line treatments without data on resistance or without data on first-line treatment (Appendix 2).

Studies includedThirty-one articles describing the rate of resistance after the failure of a first eradication therapy (2787 patients) were included in the systematic review.

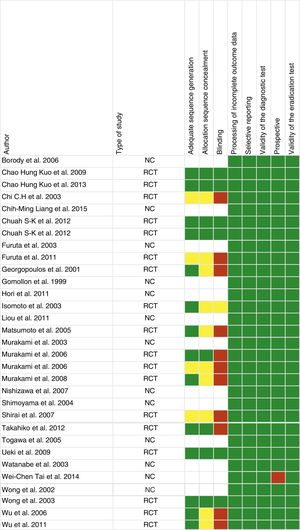

Study qualityFig. 2 shows the risk of bias assessment. Of the 31 articles, 18 were randomised clinical trials, 12 were observational and one was retrospective.

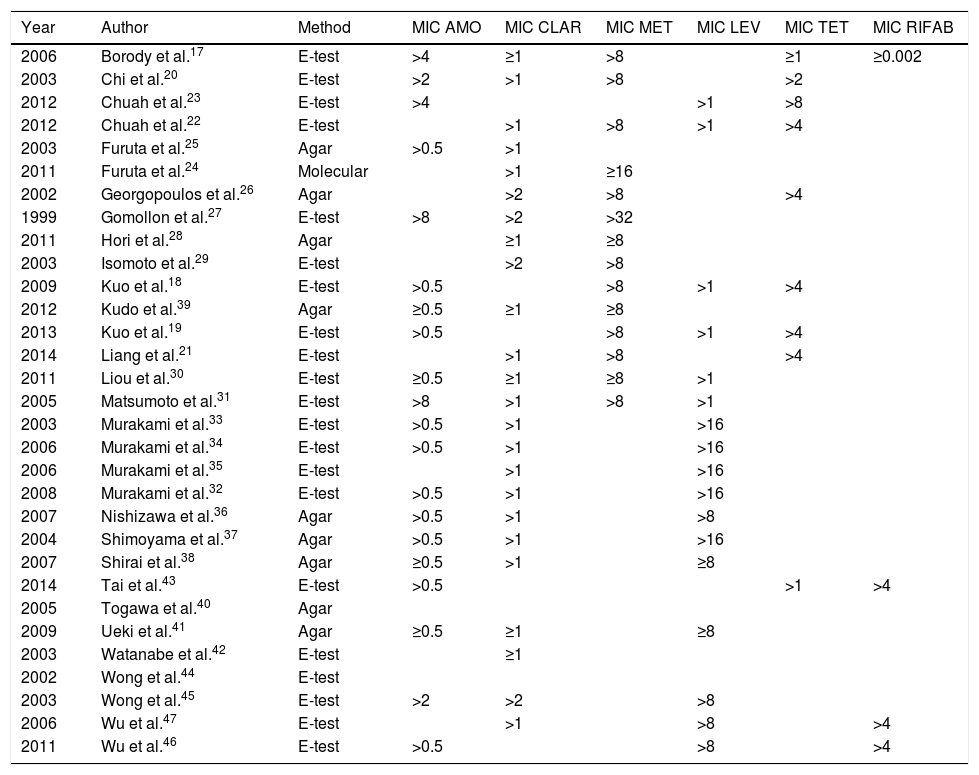

Resistance rates to antibiotics used in first-lineIn total, 2787 patients were analysed in our review; of these, resistance was determined before the second treatment in 1764 (63.3%). Additional details on the method for determining resistance and the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) are shown in Table 1.

Review articles. Methods for determining resistance.

| Year | Author | Method | MIC AMO | MIC CLAR | MIC MET | MIC LEV | MIC TET | MIC RIFAB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | Borody et al.17 | E-test | >4 | ≥1 | >8 | ≥1 | ≥0.002 | |

| 2003 | Chi et al.20 | E-test | >2 | >1 | >8 | >2 | ||

| 2012 | Chuah et al.23 | E-test | >4 | >1 | >8 | |||

| 2012 | Chuah et al.22 | E-test | >1 | >8 | >1 | >4 | ||

| 2003 | Furuta et al.25 | Agar | >0.5 | >1 | ||||

| 2011 | Furuta et al.24 | Molecular | >1 | ≥16 | ||||

| 2002 | Georgopoulos et al.26 | Agar | >2 | >8 | >4 | |||

| 1999 | Gomollon et al.27 | E-test | >8 | >2 | >32 | |||

| 2011 | Hori et al.28 | Agar | ≥1 | ≥8 | ||||

| 2003 | Isomoto et al.29 | E-test | >2 | >8 | ||||

| 2009 | Kuo et al.18 | E-test | >0.5 | >8 | >1 | >4 | ||

| 2012 | Kudo et al.39 | Agar | ≥0.5 | ≥1 | ≥8 | |||

| 2013 | Kuo et al.19 | E-test | >0.5 | >8 | >1 | >4 | ||

| 2014 | Liang et al.21 | E-test | >1 | >8 | >4 | |||

| 2011 | Liou et al.30 | E-test | ≥0.5 | ≥1 | ≥8 | >1 | ||

| 2005 | Matsumoto et al.31 | E-test | >8 | >1 | >8 | >1 | ||

| 2003 | Murakami et al.33 | E-test | >0.5 | >1 | >16 | |||

| 2006 | Murakami et al.34 | E-test | >0.5 | >1 | >16 | |||

| 2006 | Murakami et al.35 | E-test | >1 | >16 | ||||

| 2008 | Murakami et al.32 | E-test | >0.5 | >1 | >16 | |||

| 2007 | Nishizawa et al.36 | Agar | >0.5 | >1 | >8 | |||

| 2004 | Shimoyama et al.37 | Agar | >0.5 | >1 | >16 | |||

| 2007 | Shirai et al.38 | Agar | ≥0.5 | >1 | ≥8 | |||

| 2014 | Tai et al.43 | E-test | >0.5 | >1 | >4 | |||

| 2005 | Togawa et al.40 | Agar | ||||||

| 2009 | Ueki et al.41 | Agar | ≥0.5 | ≥1 | ≥8 | |||

| 2003 | Watanabe et al.42 | E-test | ≥1 | |||||

| 2002 | Wong et al.44 | E-test | ||||||

| 2003 | Wong et al.45 | E-test | >2 | >2 | >8 | |||

| 2006 | Wu et al.47 | E-test | >1 | >8 | >4 | |||

| 2011 | Wu et al.46 | E-test | >0.5 | >8 | >4 |

AMO: amoxicillin; CLAR: clarithromycin; LEV: levofloxacin; MET: metronidazole; MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration; RIFAB: rifabutin.

We analysed the prevalence of secondary resistance to the different antibiotics:

- (a)

Amoxicillin: 1729 patients were analysed. Only 10 (0.36%) developed secondary resistance.

- (b)

Clarithromycin: 1747 cultures were obtained for resistance, 1026 (58.72%) of which showed resistance.

- (c)

Metronidazole: of 68 patients assessed, 61 (89.7%) had secondary resistance to the drug.

- (d)

Lastly, of 35 patients who received the combination clarithromycin and metronidazole as first-line treatment, 18 (40.9%) were resistant to both antibiotics (Table 2).

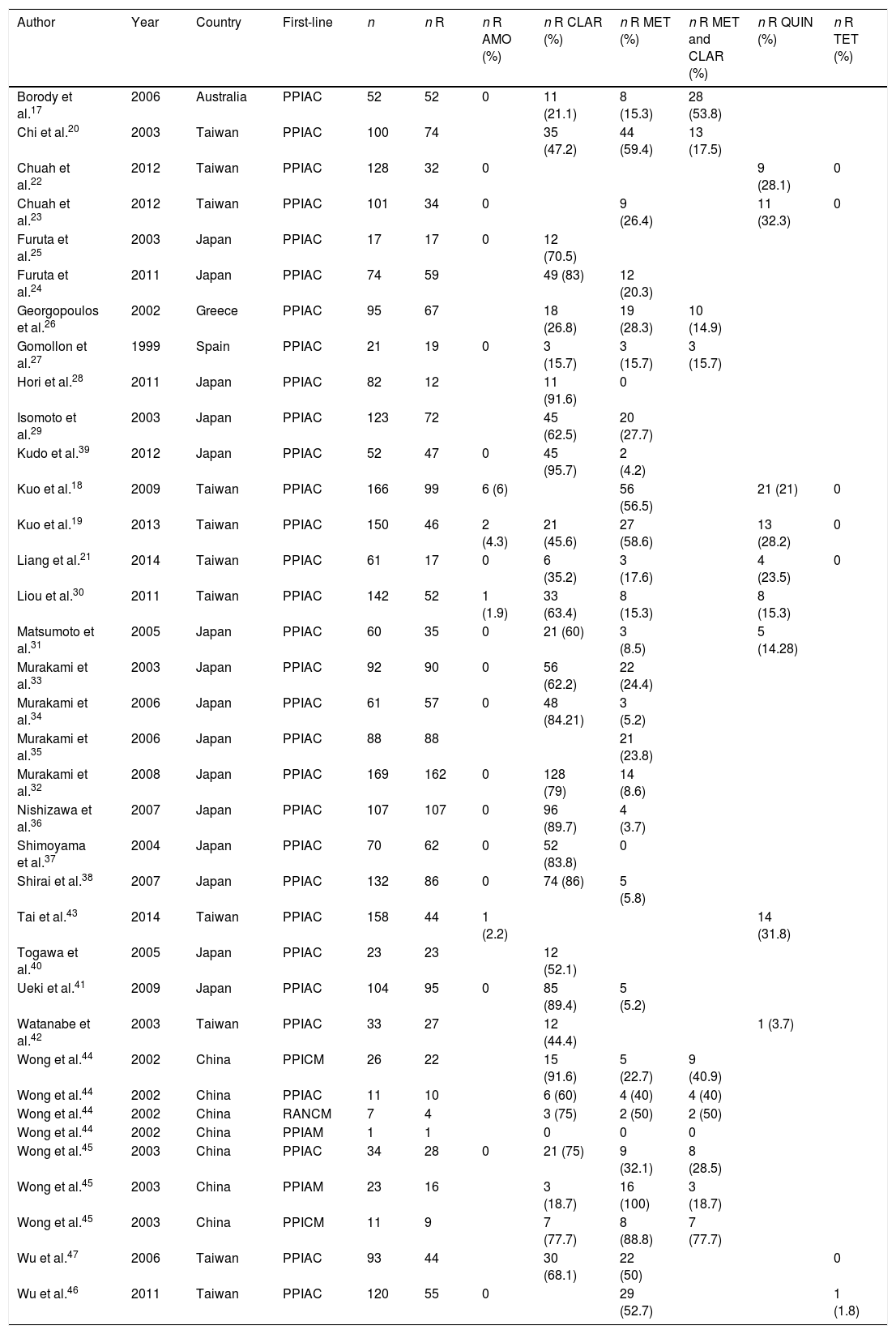

Table 2.Articles included in the review. First-line treatments received and prevalence of secondary resistance.

Author Year Country First-line n n R n R AMO (%) n R CLAR (%) n R MET (%) n R MET and CLAR (%) n R QUIN (%) n R TET (%) Borody et al.17 2006 Australia PPIAC 52 52 0 11 (21.1) 8 (15.3) 28 (53.8) Chi et al.20 2003 Taiwan PPIAC 100 74 35 (47.2) 44 (59.4) 13 (17.5) Chuah et al.22 2012 Taiwan PPIAC 128 32 0 9 (28.1) 0 Chuah et al.23 2012 Taiwan PPIAC 101 34 0 9 (26.4) 11 (32.3) 0 Furuta et al.25 2003 Japan PPIAC 17 17 0 12 (70.5) Furuta et al.24 2011 Japan PPIAC 74 59 49 (83) 12 (20.3) Georgopoulos et al.26 2002 Greece PPIAC 95 67 18 (26.8) 19 (28.3) 10 (14.9) Gomollon et al.27 1999 Spain PPIAC 21 19 0 3 (15.7) 3 (15.7) 3 (15.7) Hori et al.28 2011 Japan PPIAC 82 12 11 (91.6) 0 Isomoto et al.29 2003 Japan PPIAC 123 72 45 (62.5) 20 (27.7) Kudo et al.39 2012 Japan PPIAC 52 47 0 45 (95.7) 2 (4.2) Kuo et al.18 2009 Taiwan PPIAC 166 99 6 (6) 56 (56.5) 21 (21) 0 Kuo et al.19 2013 Taiwan PPIAC 150 46 2 (4.3) 21 (45.6) 27 (58.6) 13 (28.2) 0 Liang et al.21 2014 Taiwan PPIAC 61 17 0 6 (35.2) 3 (17.6) 4 (23.5) 0 Liou et al.30 2011 Taiwan PPIAC 142 52 1 (1.9) 33 (63.4) 8 (15.3) 8 (15.3) Matsumoto et al.31 2005 Japan PPIAC 60 35 0 21 (60) 3 (8.5) 5 (14.28) Murakami et al.33 2003 Japan PPIAC 92 90 0 56 (62.2) 22 (24.4) Murakami et al.34 2006 Japan PPIAC 61 57 0 48 (84.21) 3 (5.2) Murakami et al.35 2006 Japan PPIAC 88 88 21 (23.8) Murakami et al.32 2008 Japan PPIAC 169 162 0 128 (79) 14 (8.6) Nishizawa et al.36 2007 Japan PPIAC 107 107 0 96 (89.7) 4 (3.7) Shimoyama et al.37 2004 Japan PPIAC 70 62 0 52 (83.8) 0 Shirai et al.38 2007 Japan PPIAC 132 86 0 74 (86) 5 (5.8) Tai et al.43 2014 Taiwan PPIAC 158 44 1 (2.2) 14 (31.8) Togawa et al.40 2005 Japan PPIAC 23 23 12 (52.1) Ueki et al.41 2009 Japan PPIAC 104 95 0 85 (89.4) 5 (5.2) Watanabe et al.42 2003 Taiwan PPIAC 33 27 12 (44.4) 1 (3.7) Wong et al.44 2002 China PPICM 26 22 15 (91.6) 5 (22.7) 9 (40.9) Wong et al.44 2002 China PPIAC 11 10 6 (60) 4 (40) 4 (40) Wong et al.44 2002 China RANCM 7 4 3 (75) 2 (50) 2 (50) Wong et al.44 2002 China PPIAM 1 1 0 0 0 Wong et al.45 2003 China PPIAC 34 28 0 21 (75) 9 (32.1) 8 (28.5) Wong et al.45 2003 China PPIAM 23 16 3 (18.7) 16 (100) 3 (18.7) Wong et al.45 2003 China PPICM 11 9 7 (77.7) 8 (88.8) 7 (77.7) Wu et al.47 2006 Taiwan PPIAC 93 44 30 (68.1) 22 (50) 0 Wu et al.46 2011 Taiwan PPIAC 120 55 0 29 (52.7) 1 (1.8) AMO: amoxicillin; CLAR: clarithromycin; MET: metronidazole; PPIAC: proton-pump inhibitor, amoxicillin and clarithromycin; PPIAM: proton-pump inhibitor, amoxicillin and metronidazole; PPICM: proton-pump inhibitor, clarithromycin and metronidazole; QUIN: quinolones; R: resistant; RANCM: ranitidine, clarithromycin and metronidazole; TET: tetracyclines.

In our review we also analysed the prevalence for other antibiotics not used in first-line treatment: 4.9% resistance to quinolones and 0.05% to tetracyclines. Of the patients who did not receive metronidazole (2719), 405 (14.9%) were resistant.

DiscussionThe WHO (World Health Organisation) has classified H. pylori as high-priority on its priority pathogens list, as an infection with a high degree of resistance to antibiotics and as representing a public health problem.48 In line with other published studies,49–52 the results of our review show a high prevalence of secondary resistance to clarithromycin (>50%). The secondary resistance rates to metronidazole are even higher (89.7%). In contrast, secondary resistance to amoxicillin is rare. One interesting fact is that 40.9% have dual resistance to metronidazole and clarithromycin after treatment failure. These figures are in line with data from previous studies in which secondary resistance ranged from 46.9% to 83.3% for clarithromycin, 16.7% to 43.8% for metronidazole and 16.7% to 50% for quinolones.53

We also analysed the prevalence of resistance to other antibiotics that were not administered as first-line. Interestingly, resistance rates to quinolones were low (4.9%) and to tetracycline, almost non-existent (0.05%). In the case of quinolones, the low resistance rate may reflect both a selection of strains sensitive to the antibiotic and a low underlying prevalence. In the case of metronidazole, the “baseline” rate of resistance was 14.9%, much lower than the 89% found after treatment failure.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically assess secondary resistance rates to antibiotics. One of the limitations of our study was the conspicuous lack of data available in Western countries. Moreover, the small number of studies detected does not allow any subgroup analysis.

Our study confirms that it is advisable to avoid the re-administration of clarithromycin after a first failure of eradication therapy. The data on metronidazole, however, are less conclusive. Although different studies and reviews show that treatment with metronidazole at high doses and for 10 days or more may reverse resistance in vitro,54 a recent multicentre observational study shows that repetition of the antibiotic is associated with very low cure rates in the context of failure of a previous metronidazole treatment.55

Of the articles included in our systematic review, a third did not have adequate allocation sequence concealment and blinding of the investigators (Fig. 2). There is therefore a greater risk of bias and the results of the systematic review, as well as the quality of the results, could be affected. It should also be noted that most of the included studies were conducted in Asian populations, and only three in Mediterranean populations, meaning that they are less applicable in clinical practice in our area.

In conclusion, our study suggests that secondary resistance after an initial treatment with metronidazole and clarithromycin is very high. In contrast, resistance to amoxicillin is extremely rare, even after treatment failure.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Muñoz N, Sánchez-Delgado J, Baylina M, López-Góngora S, Calvet X. Prevalencia de las resistencias de Helicobacter pylori tras el fracaso de una primera línea de tratamiento. Revisión sistemática. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:654–662.