Although paradoxical virological and immunological response after HAART has been well studied, intestinal lymphangiectasia (IL) in HIV-1 infected patients has not previously described.

MethodsTo describe HIV patients who developed IL.

DesignClinical Case series.

Patients4 patients with HIV and IL diagnosis based on clinical, endoscopic and pathological findings.

ResultsAll four cases had prior mycobacterial infections with abdominal lymph node involvement and a very low CD4 cell count nadir. They developed intestinal lymphangiectasia despite appropriate virological suppression with HAART and repeatedly negative mycobacterial cultures. Two patients were clinically symptomatic with oedemas, ascites, diarrhoea, asthenia, weight loss; but the other two were diagnosed with malabsorption as a result of laboratory findings, with hypoproteinemia and hypoalbuminemia. Three of them were diagnosed by video capsule endoscopy.

ConclusionsIL should be considered in HIV-1 infected patients who present with clinical or biochemical malabsorption parameters when there is no immunological recovery while on HAART.

Aunque las respuestas paradójicas al tratamiento antirretroviral, con ausencia de respuesta inmunológica a pesar de buen control virológico, han sido extensamente estudiadas, no se ha descrito hasta ahora la presencia de linfangiectasia intestinal (LI) como causa de las mismas.

MétodoSerie de pacientes con infección VIH que desarrollaron LI.

DiseñoSeries de casos clínicos.

PacientesIncluye 4 pacientes que desde el año 2002 han sido diagnosticados de LI en función de los datos clínicos y los hallazgos endoscópicos y patológicos.

ResultadosLos cuatro pacientes habían sido diagnósticados previamente de infecciones por micobacterias con afectación de ganglios abdominales y presentaron un recuento de linfocitos CD4 nadir muy bajo. Todos desarrollaron LI a pesar de mantener una supresión virológica mantenida con el tratamiento antirretroviral y cultivos frente a micobacterias repetidamente negativos. Dos pacientes desarrollaron clínica asociada con edemas, ascitis, diarrea, astenia y pérdida de peso, pero en los otros dos se llegó al diagnóstico por presentar parámetros bioquímicos de malabsorción pierde proteínas. En tres de ellos se llegó al diagnóstico mediante videocápsula-endoscópica.

ConclusiónLa LI debe considerarse una causa más de falta de respuesta inmunológica al tratamiento antirretroviral, debiendo considerarse principalmente en pacientes con infección VIH y otras alteraciones clínicas o analíticas sugestivas de malabsorción.

Intestinal lymphangiectasia (IL) is a rare chronic congenital or acquired disorder characterized by exudative enteropathy resulting from morphological abnormalities of the intestinal lymphatics.1 Acquired IL is due to mechanical obstruction of lymphatic drainage which could appear in intestinal tuberculosis and other conditions.2 The functional obstruction of lymph flow leads to lymphopenia, hypoalbuminemia and hypogammaglobulinemia.1 To our knowledge there is only one previous report of IL in an HIV-1 infected patient.3

Patients and methodsWe describe 4 HIV-1 infected patients with IL, seen in the Son Llàtzer and Son Dureta Hospitals, Spain. The final IL diagnosis was based on clinical, endoscopic and pathological findings. Serum immunoglobulins, IgG, IgA and IgM were measured by nephelometry. Percentages and absolute values of CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes were determined using a four-colour panel of monoclonal antibodies against CD45, CD4, CD8 and CD3 (Cyto-STAT tetraCHROME, Beckman Coulter) and flow-count fluorospheres (Beckman Coulter), respectively. Mature and activation markers were determined by using combinations of anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD45RA, anti-CD45RO, anti-CD62L, anti-HLA-DR and anti-CD25 monoclonal antibodies (all from Beckman Coulter). The analysis was carried out in an Epics FC flow cytometer (Coulter Immunotech).

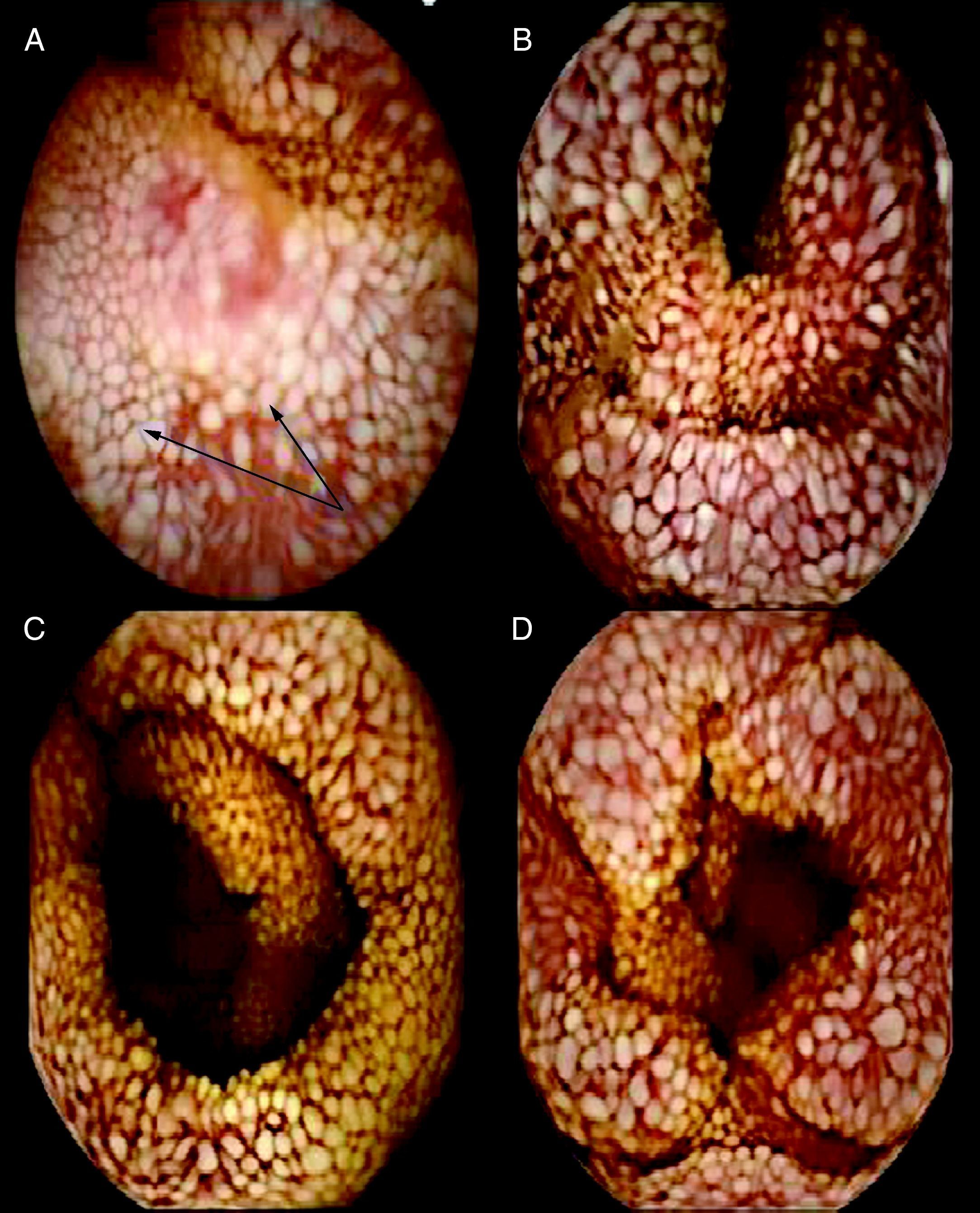

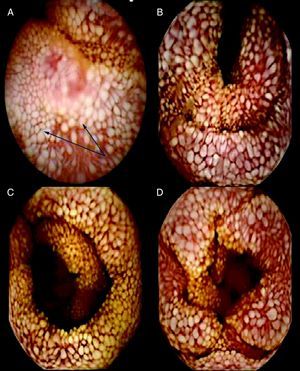

Clinical observationsCase 1In 1987, a 48-year-old woman was diagnosed with HIV-1 infection. She was co-infected with hepatitis C virus and had a disseminated tuberculosis episode in 1998, involving the lung, liver, spleen and abdominal lymph nodes. Treatment was started with isoniazid (INH), rifampin (RIF), pyrazinamide and ethambutol for 2 months, followed by INH and RIF for another 7 months. She began HAART with 2 NRTI and indinavir, which was subsequently simplified to efavirenz. Since then, she has maintained a viral load <50 copies/mL, but the CD4 cell count remained at <100 cells/μL, despite therapy with interleukin-2. From 2004 the patient presented progressive hypoproteinemia and hypoalbuminemia as well as, low levels of iron and vitamin D, with a secondary hyperparathyroidism (Table 1). The liver biopsy demonstrated chronic hepatitis C without fibrosis. The gastroscopy and a video capsule endoscopy showed small creamy-whitish plaques or nodular lesions that were well defined and covered by normal appearing small-bowel mucosa (Fig. 1A) and marked dilation of the lymphatics within the duodenum-jejunum and ileum mucosa. The small bowel biopsy specimen was compatible with IL but Ziehl-Neelsen stains were negative. Dietary treatment with low-fat diet containing medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) and mineral supplements was started, with an improvement of total proteins (5g/dL), albumin (2.5g/dL) and a return to normal of calcium and zinc levels. However, the percentage of CD4 T cells did not reach normal values (last CD4 cell count 129 cell/ μL) and the percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ naive cells (CD45RA+CD62L+) were low. The percentages of activated (DR+) CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes (8% and 14%, respectively) were similar to controls.

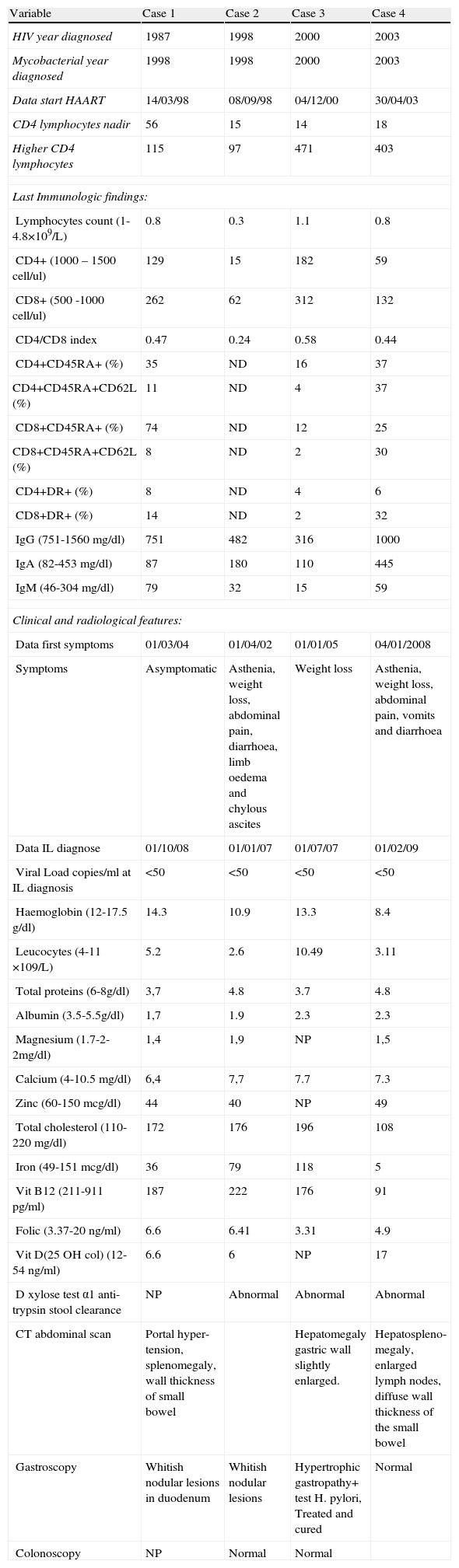

Clinical, laboratory data with phenotype of peripheral (circulating) cells and radiological findings in patients with HIV-1 and intestinal lymphangiectasia.

| Variable | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 |

| HIV year diagnosed | 1987 | 1998 | 2000 | 2003 |

| Mycobacterial year diagnosed | 1998 | 1998 | 2000 | 2003 |

| Data start HAART | 14/03/98 | 08/09/98 | 04/12/00 | 30/04/03 |

| CD4 lymphocytes nadir | 56 | 15 | 14 | 18 |

| Higher CD4 lymphocytes | 115 | 97 | 471 | 403 |

| Last Immunologic findings: | ||||

| Lymphocytes count (1-4.8×109/L) | 0.8 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| CD4+ (1000 – 1500 cell/ul) | 129 | 15 | 182 | 59 |

| CD8+ (500 -1000 cell/ul) | 262 | 62 | 312 | 132 |

| CD4/CD8 index | 0.47 | 0.24 | 0.58 | 0.44 |

| CD4+CD45RA+ (%) | 35 | ND | 16 | 37 |

| CD4+CD45RA+CD62L (%) | 11 | ND | 4 | 37 |

| CD8+CD45RA+ (%) | 74 | ND | 12 | 25 |

| CD8+CD45RA+CD62L (%) | 8 | ND | 2 | 30 |

| CD4+DR+ (%) | 8 | ND | 4 | 6 |

| CD8+DR+ (%) | 14 | ND | 2 | 32 |

| IgG (751-1560mg/dl) | 751 | 482 | 316 | 1000 |

| IgA (82-453 mg/dl) | 87 | 180 | 110 | 445 |

| IgM (46-304mg/dl) | 79 | 32 | 15 | 59 |

| Clinical and radiological features: | ||||

| Data first symptoms | 01/03/04 | 01/04/02 | 01/01/05 | 04/01/2008 |

| Symptoms | Asymptomatic | Asthenia, weight loss, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, limb oedema and chylous ascites | Weight loss | Asthenia, weight loss, abdominal pain, vomits and diarrhoea |

| Data IL diagnose | 01/10/08 | 01/01/07 | 01/07/07 | 01/02/09 |

| Viral Load copies/ml at IL diagnosis | <50 | <50 | <50 | <50 |

| Haemoglobin (12-17.5 g/dl) | 14.3 | 10.9 | 13.3 | 8.4 |

| Leucocytes (4-11 ×109/L) | 5.2 | 2.6 | 10.49 | 3.11 |

| Total proteins (6-8g/dl) | 3,7 | 4.8 | 3.7 | 4.8 |

| Albumin (3.5-5.5g/dl) | 1,7 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Magnesium (1.7-2-2mg/dl) | 1,4 | 1,9 | NP | 1,5 |

| Calcium (4-10.5 mg/dl) | 6,4 | 7,7 | 7.7 | 7.3 |

| Zinc (60-150 mcg/dl) | 44 | 40 | NP | 49 |

| Total cholesterol (110-220 mg/dl) | 172 | 176 | 196 | 108 |

| Iron (49-151 mcg/dl) | 36 | 79 | 118 | 5 |

| Vit B12 (211-911 pg/ml) | 187 | 222 | 176 | 91 |

| Folic (3.37-20 ng/ml) | 6.6 | 6.41 | 3.31 | 4.9 |

| Vit D(25 OH col) (12-54 ng/ml) | 6.6 | 6 | NP | 17 |

| D xylose test α1 anti-trypsin stool clearance | NP | Abnormal | Abnormal | Abnormal |

| CT abdominal scan | Portal hyper-tension, splenomegaly, wall thickness of small bowel | Hepatomegaly gastric wall slightly enlarged. | Hepatospleno-megaly, enlarged lymph nodes, diffuse wall thickness of the small bowel | |

| Gastroscopy | Whitish nodular lesions in duodenum | Whitish nodular lesions | Hypertrophic gastropathy+ test H. pylori, Treated and cured | Normal |

| Colonoscopy | NP | Normal | Normal | |

In 1998, a 41-year-old woman with diarrhoea and weight loss was diagnosed with HIV-1 infection and disseminated Mycobacterium avium-complex (MAC) infection (stool and duodenal biopsy cultures were positive). She began HAART with 2NRTI and 1PI with a good virological response, although the CD4 cell count remained below 50 cells/μL despite the MAC therapy with clarithromycin and ethambutol being maintained and received treatment with interleukin-2. From 2002 she presented with asthenia, weight loss, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, lower limb oedema and chylous ascites. Blood samples showed anaemia, hypoproteinemia, hypoalbuminemia, hypogammaglobulinemia, low levels of iron and vitamin D, with a secondary hyperparathyroidism (Table 1). Stool samples were repeatedly negative for bacteria, mycobacteria and parasites. In January 2007 the gastroscopy showed whitish nodular lesions and a biopsy revealed marked lymphatic dilation. Ziehl-Neelsen stains and Polymerase Chain Reaction for mycobacteria of duodenal biopsy were negative. A low fat diet, vitamin, mineral supplements and diuretics were started, and octreotide was assayed without clinical success. No immunological recovery was observed (last CD4 cell count 15 cells/μL). During follow-up she developed one episode of bacterial peritonitis, as well as a cerebral toxoplasmosis, due to a voluntary interruption of cotrimoxazole, and she died in June 2009.

Case 3In 2000 a 53-year-old man was diagnosed with HIV-1 infection as a result of a disseminated MAC disease. He had abdominal lymph nodes enlargement and stool cultures were positive. With a CD4 cell count of 14 cells/μL, he started treatment with clarithromycin and ethambutol, as well as HAART with 2NRTI and efavirenz with good virological and immunological responses. In June 2002 he stopped MAC prophylaxis, with a CD4 count of 185 cells/μL. In 2005 he was assessed due to a slight weight loss and hypoproteinemia and hypoalbuminemia (Table 1). Parasites and cultures for mycobacteria from blood and stool samples were negative. In July 2007 video capsule endoscopy showed a small-bowel mucosa with a prominent white tipped villous pattern (Fig. 1B). Histological examination revealed marked dilation of the lymphatic channels in the lamina propria with distortion of villi consistent with the diagnosis of lymphangiectasia, but Ziehl-Neelsen stains were negative. Although he started dietary treatment, vitamin and mineral supplements, serum proteins did not improve (total proteins 3.9g/dL, albumin 2.2g/dL). The patient did not achieve immunological recovery, with low CD4 T cells (182 cells /μL) and low percentages of both CD4+ and CD8+ CD45RA+CD62L naïve cells (4% and 2%, respectively). His activated T lymphocytes (CD4+DR+ 4% and CD8+DR+ 2%) did not increase.

Case 4In 2003, a 46-year-old man was diagnosed with HIV-1 infection. With a CD4 cell count 18 cells/μL he had Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia and a disseminated M. xenopi infection (lymph nodes and stool cultures were positive). He was started on HAART with 2NRTI and 1PI, with a good virological response. Therapy with clarithromycin and ethambutol was continued despite CD4 >200 cells/μL as he had persistent pancytopenia and splenomegaly. The bone marrow smears were positive for acid-fast bacilli, with repeatedly negative cultures. In January 2008 he was assessed due to, asthenia, weight loss, abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhoea. On physical examination he was shown to have, limbs oedemas, ascites, and splenomegaly. The laboratory tests showed anaemia, lymphopenia, a CD4 cell count of 166 cells/μL, viral load<50 copies/mL, hypoproteinemia and hypoalbuminemia (Table 1). Video capsule endoscopy showed diffuse intestinal lymphangiectasia affecting the duodenum and jejunum (Fig. 1C and D). Biopsy specimens revealed macrophages with foamy cytoplasm, expanding villi and lamina propria. The Ziehl-Neelsen stains were positive, but again mycobacterial cultures from blood, bone marrow and stools were negative. Therapy with ciprofloxacin, amikacin and rifabutin was added, as well as dietary and mineral supplements with an improvement of the diarrhoea, and a disappearance of the oedemas and ascites. No immunological recovery was observed during follow up; total protein: 4.9g/dL, albumin 1.8g/dL and CD4 lymphocytes: 59 cells/μL, with normal CD4 and CD8 percentages of naïve CD45RA+CD62L+ cells (37% and 30%, respectively). We found a higher percentage of activated CD8+DR+ cells (32%) in this patient.

DiscussionWe describe four AIDS patients with previous disseminated mycobacterial infections, good antiretroviral adherence and long term virological suppression who presented with hypoproteinemia, other malabsorption laboratory data and low CD4 lymphocytes, which could only be explained by IL, although only two of them were clinically symptomatic. In three patients, mycobacteria were isolated from the gastrointestinal tract and one was diagnosed of disseminated tuberculosis, due to liver, spleen and lymph nodes enlargement, but only sputum cultures were positive.

IL is associated with an impairment of humoral and cellular immunity, which is present in over 90% of the patients. B-cell defect is characterized by low immunoglobulin levels and poor antibody response, a T-cell defect due to lymphocytopenia, prolonged skin allograft rejection, and impaired in vitro proliferative response to various stimulants. T cell lymphocytopenia is severe in both CD4 and CD8 subsets, and loss of naïve CD45RA+ CD62L+ was noted,4 as we observed in two of the three patients studied. A somewhat selective loss of CD4 T-cells with inversion of the CD4/CD8 ratio similar to HIV infection has been reported.4–6 The main mechanism of lymphopenia in IL is the leakage of lymph fluid into the small-bowel lumen, but an important T-cell activation and apoptosis by an increase in CD95/Fas expression similar to HIV-1 infections has been reported.7 We also found a patient with high levels of activated (DR+) CD8+ T cells. The first two patients had paradoxical virological and immunological responses after HAART, with no response to interleukin-2 treatment, and the other two showed a CD4 decrease on IL diagnosis, despite remaining with an undetectable viral load. In IL, lymphopenia is not always associated with residual T cell dysfunction, and these patients generally do not develop opportunistic infections, although skin bacterial infections have been described.1,7 We did not observe infections during follow-up, with the exception of one episode of bacterial peritonitis attributed to medical manipulation, and toxoplasma encephalitis after stopping prophylaxis.

Sometimes diagnosis can be difficult due to the segmental nature of IL lesions in the small bowel, as reflected in the 37.2 month mean delay in our cases. Three patients were diagnosed by video capsule endoscopy, which allowed us to discover undetected lesions by conventional endoscopy.8,9

Treatment of IL is based on dietary supplements with low-fat and MCT, and mineral supplements,10 but in our experience only partial response was achieved in two cases.

In conclusion, IL should be considered in HIV-1 infected patients with previous mycobacterial infections, who present with malabsorption, hypoproteinemia and with no immunological recovery while on HAART.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Dr. Carmen Garrido (Serv Digestivo Hospital Son Dureta), Dr Carles Dolz (Servicio Digestivo Hospital Son Llatzer), Jonathan McFarland (English correction-editing).