The use of endovascular catheters is a routine practice in secondary and tertiary care level hospitals. The short-term use of peripheral catheters has been found to be associated with the risk of nosocomial bacteraemia, resulting in morbidity and mortality. Staphylococcus aureus is mostly associated with peripheral catheter insertion. This Consensus Document has been prepared by a panel of experts of the Spanish Society of Cardiovascular Infections, in cooperation with experts from the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine, Spanish Society of Chemotherapy, and the Spanish Society of Thoracic-Cardiovascular Surgery, and aims to define and establish guidelines for the management of short duration peripheral vascular catheters. The document addresses the indications for insertion, catheter maintenance, registering, diagnosis and treatment of infection, indications for removal, as well as placing an emphasis on continuous education as a drive toward quality. Implementation of these guidelines will allow uniformity in use, thus minimizing the risk of infections and their complications.

El uso de catéteres vasculares es una práctica muy utilizada en los hospitales. El uso de catéteres venosos periféricos de corta duración se ha asociado con un elevado riesgo de bacteriemia nosocomial, lo que comporta una no despreciable morbilidad y mortalidad. La etiología de estas infecciones suele ser frecuentemente por Staphylococcus aureus, lo que explica su gravedad. En este documento de consenso, elaborado por un panel de expertos de la Sociedad Española de Infecciones Cardiovasculares con la colaboración de expertos de la Sociedad Española de Medicina Interna, la Sociedad Española de Quimioterapia y la Sociedad Española de Cirugía Torácica-Cardiovascular, pretende establecer unes normas para un mejor uso de los catéteres venosos periféricos de corta duración. El Documento revisa las indicaciones para su inserción, mantenimiento, registro, diagnóstico y tratamiento de las infecciones derivadas y las indicaciones para su retirada; haciendo énfasis en la formación continuada del personal sanitario para lograr una mayor calidad asistencial. Seguir las recomendaciones del consenso permitirá utilizar de una manera más homogénea los catéteres venosos periféricos minimizando el riesgo de infección y sus complicaciones.

The use of endovascular catheters is generalized practice in the hospital setting.1 A recent prevalence study showed that 81.9% of patients admitted to Internal Medicine services are inserted with one or more catheters, out of which 95.4% are short duration peripheral lines.2 It has also recently been documented the increasing influence of peripheral catheters as a driver for nosocomial bacteremia with high associated morbidity and mortality.3–5 Several studies have shown that the risk of bacteremia related to a peripheral venous catheter (PVC) is similar to that of central venous lines6 with an estimate of 0–5 bacteremia episodes per 1000 catheter-days in admitted adult patients.4,6 Furthermore, the vast majority of cases of PVC-related bacteremia are S. aureus bacteremia; this is different from central venous lines, being S. epidermidis the most frequent isolated pathogen in the latter setting.3,4 This yields a higher complication rate including nosocomial endocarditis thus making treatment difficult. There are several guidelines and consensus documents on prevention, diagnosis and treatment of central venous catheter-related infections7–10 that have greatly contributed to reduce the infection rate and facilitate its management, especially in Intensive Care Units (ICU). However, there is scanty literature focusing on short duration peripheral catheters which are those mostly used out of the ICU setting.1,11 Several observational studies have shown that there is lack of knowledge on how to use PVC by the attending staff12 and on the opportunities to improve its handling.1,12–14

ObjectiveThe objective of this Consensus Document is to review evidence and make recommendations for management of short duration PVC in adults. This will allow uniformity in usage thus minimizing the risk of infection and its complications.

Participating organizationsThis Consensus Document has been elaborated by a panel of experts of the Spanish Society of Cardiovascular Infections (SEICAV) in cooperation with experts from the following scientific societies: Spanish Society of Internal Medicine (SEMI), Spanish Society of Chemotherapy (SEQ) and Spanish Society of Thoracic-Cardiovascular Surgery (SECTCV).

MethodsThe recommendations for insertion, handling and removal of PVCs and also what to do when suspecting infection (diagnosis) and its treatment are issued based on the best scientific available evidence or, when not available, on expert opinion. Therefore, PubMed (www.PubMed.org) literature search between 1986 and 2015 has been performed. This is a well-known free access resource established and maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) of the National Library of Medicine (NLM) of the USA, which provides free access to MEDLINE, the database of citations and abstracts of the NLM. It currently stores over 24 million citations from over 5600 biomedical journals.

In our PubMed search using the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms “management of peripheral venous catheter” (N=363) and “peripheral catheter-related bacteremia” (N=260), studies related to newborns or pediatric patients and studies on peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC) were discarded. MeSH terms is the NLM controlled vocabulary thesaurus used for indexing articles for PubMed (www.pubmed.org). Guidelines on prevention, diagnosis and treatment of catheter infection were reviewed.7–10

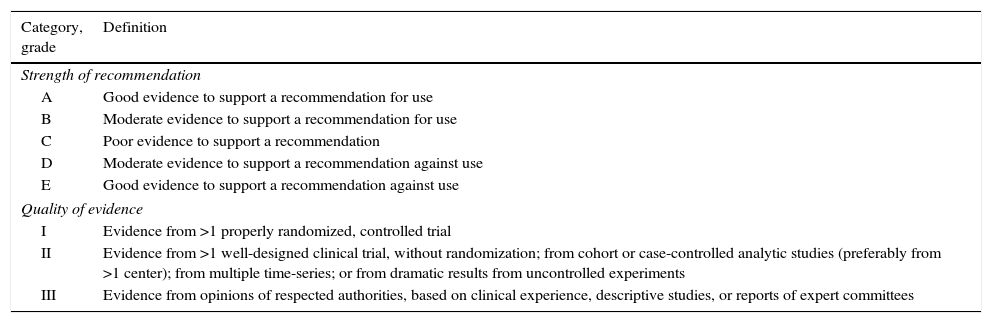

The levels of evidence and strength of recommendations according to the below definitions will be shown in bold within brackets when a recommendation is made in the text.

DefinitionsTable 1 describes the levels of evidence and the strength of recommendations according to the criteria of the Infectious Disease Society of America (ISDA).15

Infectious Disease Society of America – United States Public Health Service Grading System for ranking recommendations in clinical guidelines.15

| Category, grade | Definition |

|---|---|

| Strength of recommendation | |

| A | Good evidence to support a recommendation for use |

| B | Moderate evidence to support a recommendation for use |

| C | Poor evidence to support a recommendation |

| D | Moderate evidence to support a recommendation against use |

| E | Good evidence to support a recommendation against use |

| Quality of evidence | |

| I | Evidence from >1 properly randomized, controlled trial |

| II | Evidence from >1 well-designed clinical trial, without randomization; from cohort or case-controlled analytic studies (preferably from >1 center); from multiple time-series; or from dramatic results from uncontrolled experiments |

| III | Evidence from opinions of respected authorities, based on clinical experience, descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees |

PVC is a catheter shorter than 7.62cm (3in.).

Sepsis is a systemic inflammatory response syndrome secondary to an infection.16 The term phlebitis is used if one of the following criteria was fulfilled: swelling and erythema >4mm, tenderness, palpable venous cord, pain or fever with local symptoms. Isolated swelling is not defined as phlebitis.

InsertionWhen?PVC will be inserted when the duration of a given endovenous therapy is expected to be shorter than 6 days and the PVC will not be used for major procedures as hemodialysis, plasmapheresis, chemotherapy, parenteral nutrition, monitoring or administration of fluid large volumes. When any of these circumstances is to be expected, it is preferable to insert a single-, double- or triple-lumen central venous line (peripherally inserted or not) as the risk of chemical phlebitis, the need for high-speed volume infusion or frequent manipulations do not support a short catheter (I-A).17,18 An isolated transfusion does not need a central venous line insertion. Before placing any venous line, even peripheral, it is mandatory the evaluation of the actual need. Venous lines are often placed as routine; this meant to be an act reflecting the provision of care. It is also frequently shown that to treat the patient a “prophylactic” line was not mandatory. A study showed that up to 35% of peripheral venous lines place in the emergency department are unnecessary.19

Where?A PVC can be inserted in every accessible vein. However, upper extremity veins are preferable for patient comfort and lesser risk of contamination. Some studies reported a higher risk of phlebitis after lines were placed at the cubital crease, thus becoming preferable avoiding this site in benefit of arm, forearm or dorsal aspect of the hand/wrist20,21 (II-A).

Furthermore, other patient-related factors like accessibility to the venous system or comfort after insertion have to be taken into account. It does not make much sense to insert a PVC onto a central vein (III-A).

How?The insertion of PVC must be performed under maximal aseptic techniques. It is not necessary to prep a surgical field as it is the when inserting a central venous line. The skin must be disinfected with 2% alcoholic chlorhexidine solution or, if not available, with a 70% iodine or alcohol solution9,22,23 (I-A).

The insertion site should not be touched after disinfection. The catheter must be handled from its proximal end when inserted. The caregiver inserting the PVC must previously perform hand hygiene with water and soap and/or wash hands with alcohol solution. Single-use clean gloves must be used. An enhanced asepsis is not required if the endovenous segment of the PVC is not manipulated9 (III-B). As it is the case when inserting central venous lines, the use of additional protection measures like facemask is not recommended. However, this is a topic for consideration and analysis if in a given institution higher than expected rates of PVC-related bacteremia are observed.

Sterile gauze dressing or semi permeable transparent sterile dressing to cover the insertion site will be used23,24 (II-A). Sterile gauze dressing will be inspected and replaced every other day and transparent dressing should not stay in place over 7 days.9 If there is humidity, sweating or blood it is more appropriate to use non-occlusive gauze dressing24,25 (III-B). Revision or replacement of dressing must be performed with single-use clean gloves.9

PVCs placed on urgent basis or without considering minimal hygiene rules must be removed and replaced before 48h to avoid the risk of infection17,26,27 (II-A).

The use of techniques facilitating identification of veins as laser or ultrasound28,29 in patients with poor venous flow are also recommended for insertion. However, these techniques do not reduce the risk of infection. A meta-analysis on this topic showed that its routine use is not justified30 (I-A).

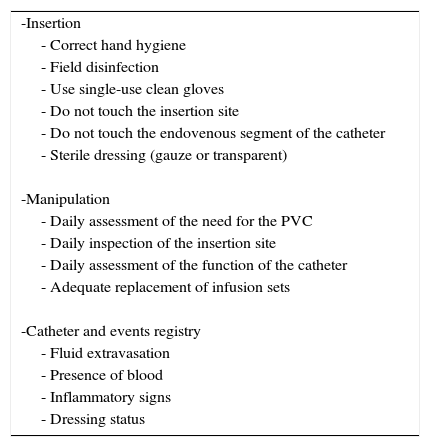

ChecklistThe adhesion to recommendations in the form of checklist is associated to better results in prevention of post-insertion complications after insertion of central venous lines and PVCs10,31 (I-A). This is reflected in Table 2.

Checklist for an appropriate manipulation of peripheral catheters. If these are not fulfilled, the prompt removal of the catheter is advised (Evidence A).

| -Insertion |

| - Correct hand hygiene |

| - Field disinfection |

| - Use single-use clean gloves |

| - Do not touch the insertion site |

| - Do not touch the endovenous segment of the catheter |

| - Sterile dressing (gauze or transparent) |

| -Manipulation |

| - Daily assessment of the need for the PVC |

| - Daily inspection of the insertion site |

| - Daily assessment of the function of the catheter |

| - Adequate replacement of infusion sets |

| -Catheter and events registry |

| - Fluid extravasation |

| - Presence of blood |

| - Inflammatory signs |

| - Dressing status |

The catheter and the need for usage have to be assessed daily. It is advisable to remove the PVC if it is not necessary as the risk of infection or phlebitis gradually increases as PVC days go by18,32,33 (II-A). It is advisable to insert new PVC, if required, than keeping in place an inactive line that might be useful at later stage.

The status of the insertion site must also be assessed daily, seeking for eventual discomfort/symptoms at the endovascular segment suggesting early stages of phlebitis and checking its functional status. Phlebitis should be suspected if any of the following signs develop: warmth, tenderness, erythema or palpable cord. In an abnormality at the insertion site is detected, dressing must be removed and the site inspected34,35 (III-A). The catheter must then be removed and its tip sent for Microbiology according to the criterion of the attending physician17 (III-A).

No antiseptic cream shall be used at the insertion point36 (III-C).

Every manipulation of the catheter must be performed with single-use clean gloves. There is no consensus on the type of connectors to be used. It is preferable a three-way stopcock than caps requiring connection-disconnection after every use. Closed connectors for catheter access can be used as long as they are disinfected with alcohol-impregnated wipes at every attempt to access the catheter37 (II-A).

A meta-analysis revealed that there are no advantages of replacing the infusion system earlier than 96h38,39 (I-A) other when they are used for blood transfusion or infusion of lipid emulsions (should this be the case, they have to be replaced every time). There is no evidence that neither antibiotic prophylaxis at insertion nor the antibiotic-lock are cost-efficient to keep PVC free from infection.

RegistryIt is mandatory to keep daily record of characteristics and conditions of the catheter. In this registry the type of catheter, insertion date, anatomic location, daily inspection of dressing, removal date and cause of removal (malfunction, infection, not required, …) must be recorded (III-A). The lack of a registry is synonymous of lack of knowledge on how to use catheters, their complications and the inability to establish corrective measurements should an event occur.40 These registries should ideally be electronically supported to facilitated data collection and analysis.

RemovalWhen?As there is a causal relationship between the duration of PVC and the risk of phlebitis, the need for systematic replacement of PVC at a given time interval to avoid local and systemic complications has been proposed.18,41,42 However, this strategy may render expensive the provision of care by increasing in over 25% the cost and number of catheters to use and make the catheter resite more difficult.42,43 This, on the other side, has not avoided the complications of the use of the new catheter regardless of the inconveniences of replacing a line for the patient and caregiver.

More recently, prospective and randomized studies comparing systematic replacement at 72h versus clinically indicated replacement of PVC did not found statistically significant differences in the incidence of phlebitis/local infection/bacteremia and the number of malfunctioning catheters both in hospitalized patients and in patients on home therapy.18,41–51 These observations support the replacement of PVC only when indicated (I-A).

Systematic removal of PVC after 3–4 days is not supported, although it is not advised to keep PVC in place beyond 5 days (III-B).

Although keeping in place an unused catheter increases the risk of phlebitis,51 it is not clear if they must be rinsed with normal saline or heparin. It seems that the risk of phlebitis is reduced with heparin but it continues to be at 45%,52 thus being removal advisable if unused. Therefore, unused catheters should not be kept in place as the risk of inflammation and infection increases10,53–55 (I-A).

PVC must be removed if the following circumstances apply: end of therapy, signs of chemical phlebitis, malfunction, suspicion of infection or suspicion of inappropriate insertion or manipulation as in cases of vital emergency56,57 (II-A).

How?Simple removal will be performed with single-use clean gloves and gauze dressing applied thereafter. Removal for suspected infection implies sending the tip of the catheter (2–3mm of distal end) in a sterile container for Microbiology. In the latter case, single-use sterile gloves and sterile instrument to cut the tip of the PVC must be used. Only catheters with suspected infection must be sent for Microbiology (III-A). There will be suspected infection if fever or signs of sepsis without evident focus and/or suppurated phlebitis appeared. Chemical phlebitis alone is not enough to submit the catheter for Microbiology. It has to be reminded that catheter-related bacteremia may develop without any suspicion that the catheter may be the cause.8,58

DiagnosisPVC infection shall be suspected when a patient with one or more PVC develops fever and/or signs of sepsis without additional clinical focus. Under this circumstance, past history of inappropriate manipulation and prolonged duration support a PVC-suspected origin of infection. Septic phlebitis or suppuration at the insertion site support this hypothesis58,59; however simple chemical phlebitis may cause low-grade fever.

If infection is suspected, 2–3 samples for blood culture must be collected. Sampling from PVC must be performed under aseptic conditions. A cotton swab should be used to take samples from purulent exudate if present. As PVCs should be of short duration and of easy replacement it is not justified to keep a catheter in situ while awaiting results from Microbiology if infection is suspected (III-B). We then believe that conservative diagnostic techniques for diagnosis of infection are not applicable60,61 (III-A). Gram stain of a PVC segment may quickly draw the attention on the possibility of infection.62

TreatmentIn the treatment of PVC infection, the first step is removal of the PVC as it has been mentioned above. Once the PVC is removed and blood samples taken for culture, the need for empirical antibiotic treatment will be related to the clinical condition of the patient (including fever and elevation of biomarkers). Treatment should be directed to PVC bacteremia. Isolated positive tips cultures do not need antibiotic treatment.

If empirical antibiotic treatment is initiated, Gram-positive cocci (including methicillin-resistant S. aureus) and Gram-negative bacilli (including P. aeruginosa) must be addressed according to individual patient risk factors and the institutional flora. Other possible etiologies, albeit infrequent, have to be considered in special subsets of patients as those previously treated with antibiotics, with multiple comorbidities, immune depressed or hospitalized for long periods of time.63S. aureus has become an increasingly impactful etiologic pathogen for bacteremia as it has been shown in several studies.3,4,64–66 For bacteremia related to central venous catheters, the etiology is well diversified.

A reasonable empirical regimen is a combination of daptomycin and a β-lactam active against P. aeruginosa. In patients with β-lactam allergies, aztreonam, an aminoglycoside or a quinolone could be an alternative. In any case, treatment should follow sensitivity patterns at 24–72h after cultures are taken67,68 (I-A).

The duration of antibiotic treatment will be related to the isolated pathogen. S. epidermidis can be treated with removal of PVC if no other inert material that can be colonized and/or infected exists; duration of treatment should not be longer than 7 days. If no antibiotic treatment is given, the patient must be symptom-free and cultures must be negative upon removal of PVC.

A different situation is S. aureus or C. albicans infection as those require a minimum of 14 days of treatment69 and follow-up cultures at 72h. Secondary infectious foci like endocarditis and/or osteomyelitis must be ruled out.70 This is even more important if bacteremia persists after removal of the PVC thus indicating a more prolonged presence of bacteria in the blood stream.70–73 This Consensus Document does not pretend reviewing the treatment of S. aureus or other bacteremias and the reader is referred to specific guidelines.70,71 Gram-negative bacilli infections usually need 7–14 days of treatment after removal of PVC and after the first negative blood culture is confirmed.7

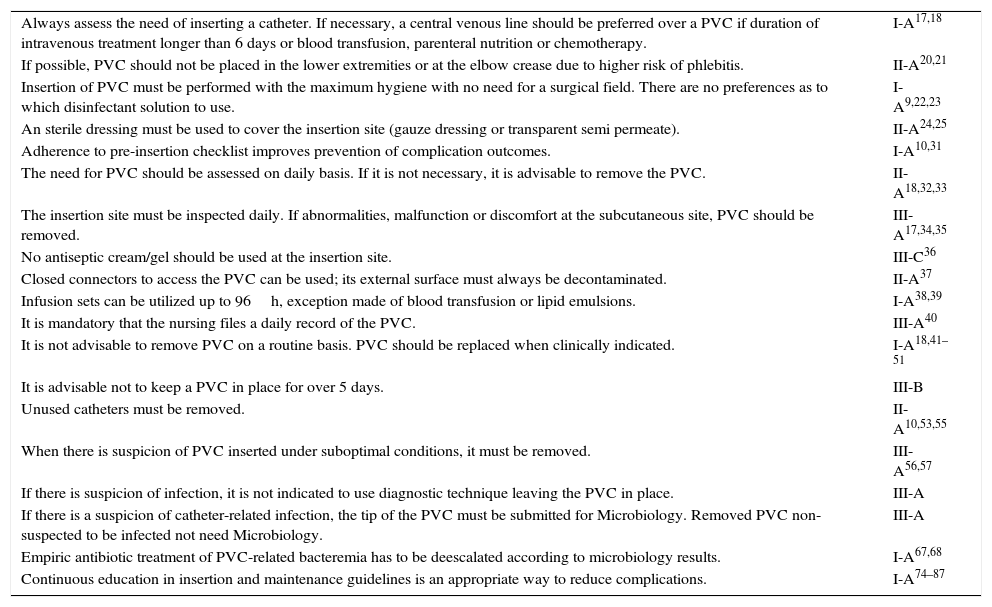

Continuous educationContinuous education of healthcare caregivers on the indications for PVC insertion and the convenience of having PVC inserted is necessary. It is necessary to periodically remind the nursing staff inserting PVC the guidelines for insertion and maintenance74–81 (I-A). Table 3 summarizes the recommendations and degree of evidence and references as produced in this document. The lack of a continuous education program leads to relaxation of the norm, abandonment of good clinical practices and increase in infection and complication rates. On the contrary, specific educational programs help in reducing infection rates.82–87 There are different ways to provide education. Education among peers has shown the best benefits in guideline follow-up as the staff is engaged in education.

Summary of recommendations and degree of evidence and (references) (see - 1).

| Always assess the need of inserting a catheter. If necessary, a central venous line should be preferred over a PVC if duration of intravenous treatment longer than 6 days or blood transfusion, parenteral nutrition or chemotherapy. | I-A17,18 |

| If possible, PVC should not be placed in the lower extremities or at the elbow crease due to higher risk of phlebitis. | II-A20,21 |

| Insertion of PVC must be performed with the maximum hygiene with no need for a surgical field. There are no preferences as to which disinfectant solution to use. | I-A9,22,23 |

| An sterile dressing must be used to cover the insertion site (gauze dressing or transparent semi permeate). | II-A24,25 |

| Adherence to pre-insertion checklist improves prevention of complication outcomes. | I-A10,31 |

| The need for PVC should be assessed on daily basis. If it is not necessary, it is advisable to remove the PVC. | II-A18,32,33 |

| The insertion site must be inspected daily. If abnormalities, malfunction or discomfort at the subcutaneous site, PVC should be removed. | III-A17,34,35 |

| No antiseptic cream/gel should be used at the insertion site. | III-C36 |

| Closed connectors to access the PVC can be used; its external surface must always be decontaminated. | II-A37 |

| Infusion sets can be utilized up to 96h, exception made of blood transfusion or lipid emulsions. | I-A38,39 |

| It is mandatory that the nursing files a daily record of the PVC. | III-A40 |

| It is not advisable to remove PVC on a routine basis. PVC should be replaced when clinically indicated. | I-A18,41–51 |

| It is advisable not to keep a PVC in place for over 5 days. | III-B |

| Unused catheters must be removed. | II-A10,53,55 |

| When there is suspicion of PVC inserted under suboptimal conditions, it must be removed. | III-A56,57 |

| If there is suspicion of infection, it is not indicated to use diagnostic technique leaving the PVC in place. | III-A |

| If there is a suspicion of catheter-related infection, the tip of the PVC must be submitted for Microbiology. Removed PVC non-suspected to be infected not need Microbiology. | III-A |

| Empiric antibiotic treatment of PVC-related bacteremia has to be deescalated according to microbiology results. | I-A67,68 |

| Continuous education in insertion and maintenance guidelines is an appropriate way to reduce complications. | I-A74–87 |

It is advisable that the infection and complication rates are periodically disclosed to the staff in charge of inserting PVCs. This is positive reinforcement on guideline/protocol follow-up and a warning if deviations occur. Furthermore, the adherence to the checklist can be monitored (Table 2).

Source of fundingNo external funding sources.

Conflict of interestNo conflicts of interest declared.

This article has also been published in Rev Esp Quimioter 2016;29(4).