This paper provides a critical analysis of the ongoing asylum policy of the United States, as the largest receptor of asylum claims in the industrialized world, to explain how it violates the principle of Non- Refoulement established in Article 33 of the 1951 Convention of Relating to the Status of Refugees and the1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees. The study will focus on the context of the treatment the United States gives to asylum seekers who arrive by sea or other means, expedited removal proceedings, the anti-terrorism measures as exception to the Principle of Non-Refoulement, and the restrictive interpretation of the Refugee concept.

Este artículo busca mostrar un análisis crítico de la actual política de asilo de los Estados Unidos, como el más grande receptor de peticiones de asilo en el mundo industrializado, para explicar cómo viola el principio de no-devolución establecido en el artículo 33 de la Convención de 1951 sobre el Estatuto de los Refugiados. El estudio se centrará en el contexto del trato que los Estados Unidos le da a solicitantes de asilo que arriban a través de vías marítimas u otros medios, procedimientos expeditos de expulsión, medidas anti-terroristas como excepción al principio de no-devolución, y la interpretación restrictiva del concepto de refugiado.

Cet article prétend montrer une analyse critique de l’actuelle politique d’asile des États-Unis comme le plus grand récepteur des demandes dans le monde industrialisé, pour exprimer comment il enfreint le principe de non-refoulement établit dans l’article 33 de la Convention de 1951 relative au statut des réfugiés. L’étude va se centrer dans le contexte du traitement que les États-Unis donne aux demandeurs d’asile qui arrivent à travers des voies maritimes ou par d’autres moyens, démarches administratives rapides d’expulsion, mesures contre terroristes comme une exception au principe de non-refoulement et l’interprétation restrictive du concept de réfugié.

Through the history of mankind, for several reasons, the World has always suffered the displacement of persons from one country to another. After World War II, the amount of people facing persecution, lead to the signing of the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (the 1951 Convention).1 In the beginning, the 1951 Convention only protected European refugees, victims of the Great War, but this figure was extended to Non- European refugees as well, with the signing of the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees.2

The 1951 Convention establishes in article 33 the so-called Principle of Non-Refoulement. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), this principle is “the cornerstone of asylum and of international refugee law” and it is considered part of the customary international law.3

This Principle teaches that “No Contracting State shall expel or return (“refouler”) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion”.4

It would be plausible to think that, redacted in those terms, the Principle of Non-Refoulement does not possess any discussion; however, several issues arise from its interpretation when confronted with the asylum policy of the United States. The first problem is related to the interpretation of the concept of refugee. This is very important because a person who is qualified as a refugee has the right to seek asylum and therefore cannot be returned to his or her country of origin. About this, the United States tends to make narrow interpretations of the concept of refugee, limiting in that way the right of asylum and, consequently, the right to not being subject to Refoulement, as we will discuss further in part 3.1 of this paper.

The second concern is about the effects of the Principle of Non-Refoulement in spite of the fact that the UNCHR has explained its extraterritorial effects. As a direct consequence, nations are not allowed to “catch” individuals who are trying to enter their borders, and return them to their countries where there exists the possibility they will face persecution. However, the asylum policy of the United States is set up to prevent potential asylum seekers to arrive in their jurisdictions, so they cannot request asylum legitimately; and thus to be able to return them to the countries where they came from, without an analysis of whether or not their life or personal integrity will face any danger.

Finally, because Article 33(2) of the 1951 Convention brings some exceptions to the application of the Principle of Non-Refoulement,5 difficulties with its interpretation arise. We will argue that the United States asylum policies are designed to make narrow interpretations of the concepts involved in the exceptions, bringing as a consequence the expulsion of refugees, who otherwise would not be expected to fall under Article 33(2) of the 1951 Convention.

We will focus on the study of the asylum policy of the United States, as the main receptor of asylum claims in the industrialized world,6 to determine that, in several aspects and for different reasons, their policy is not consequent with the Principle of Non-Refoulement as explained above, especially, in cases related to the treatment the United States give to asylum seekers who arrive by sea or other means, expedited removal proceedings, the anti-terrorism measures as an exception to the Principle of Non-Refoulement, and the restrictive interpretation of the Refugee concept.

II. The Principle of Non-Refoulement in International LawAs described above, the Principle of Non-Refoulement is mainly established by article 33 of the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol.7 The obligatory nature of the Principle of Non-Refoulement is not only found in international instruments which contain it, but also, in the character of norm of customary international law that has been attributed to the Principle, which means it is mandatory for every nation in the international community.8 The UNCHR has said that because Art. 33 of the 1951 Convention do not permit reservations, “the principle of Non-Refoulement is a norm of customary international law based “on a consistent practice combined with recognition on the part of nations that the principle has a normative character”.9

In the same line, Fernandez has established that the Principle of Non-Refoulement became an obligation of customary International Law, created by the practice of individual nations and crystalized through the Declaration on Territorial Asylum G.A. res. 2312 (XXII) and the Geneva Convention.10

Even more, we can say that the Principle of Non-Refoulement is evolving to become a norm of Jus cogens, as it is not subject to derogation.11 According to Mariño Menéndez, the obligation of Non-Refoulement is a peremptory norm of general international law or Jus Cogens, and it forms part of the hard core of the “public order” of the international community.12 Now, a nation may be considered to be in violation of this obligation when it includes in its asylum policy measures that amount directly or indirectly to the expulsion or deportation of refugees; their return to countries of origin or unsafe third countries; the establishment of instruments to prevent their entry (such as electrified fences or walls); the rejection of stowaway asylum seekers; the Non recognition of the extraterritorial effects of Non-Refoulement Principle in order to justify interdictions on the high seas; or the extradition13 to countries where the life, freedom, or personal integrity of the refugee or asylum seeker may be threatened.14

As a consequence, the Principle of Non-Refoulement supposes not only that refugees or asylum seekers shall not be returned to a country where they are in danger, but also that refugees or asylum seekers cannot be prevented from being able to request protection, even if they enter unlawfully,15 or if they are on the border.

1. Main Problems Arising from the Anterpretation of the Principle of Non-Refoulement16A. Problems with the Interpretation of the Concept of RefugeeIt is indispensable to clarify the concept of refugee, because nations possess a duty to protect refugees and asylum seekers against their return to places where their lives or freedom may be threatened, until those threats no longer exist.17

This point is even more important for asylum seekers since the status of refugee is a conditio sine qua non to seek asylum in another country. Thus, every refugee may seek asylum, but, although there is a presumption that every asylum seeker has the status of refugee, it can be otherwise disproven in order to deny that protection.18

The 1951 Convention prescribes in its article I that the term “refugee” shall apply to any person, who possessing a:

Well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.

Thus, individuals deemed as refugees under the 1951 Convention need to be outside their country of origin, be unable or unwilling to seek or take advantage of the protection of that country, or to return there due to a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.19

In this regard, the UNHCR has insisted in a broader interpretation of the concept of refugee as it appears in the 1951 Convention. For instance, the UNHCR in its guidelines,20 has urged the parliaments to implement expanded refugee definitions such as those adopted by the Organization of African Unity (OAU) Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa, or the Cartagena Declaration, because these instruments consider refugees to be not only persons who have a well-founded fear of persecution, but also persons who were forced to leave their country on account of serious alterations of the public order, occupation, external aggression, foreign domination, violence, internal conflicts or massive violations of human rights. Consequently, many countries have included those categories of refugees into its municipal law.21

However, the concept of refugee is not of a peaceful discussion within the doctrine. Fernandez affirms that there is not a uniform concept of refugee in international law because every nation regulates it in a different form within its legislation. Furthermore, Mariño Menéndez pointed out that the 1951 Convention has numerous flaws, among which he cited: the lack of clarity of the concept “well-founded fear of being persecuted”, the term “persecution” being inappropriate, and the fact that it does not make reference to questions of first asylum, nor to the establishment of internal procedures to select refugees.22

Also, as the determination of the status of refugee is a discretional matter of each nation, it may involve issues of politics. For instance, China has an agreement with North Korea to return any national of that country found in China without the proper documents. Therefore, it is a policy of China not to examine asylum claims from North Koreans and to return them to their country.23 In cases like that, the concept of refugee is reduced to what it is political convenient for a nation.

On the other hand, the concept of refugee may be narrowly interpreted by administrative or judicial authorities of a nation, when referring to the grounds on account of which the “well-founded fear of persecution” is required. For instance, the term “membership of a particular social group” has been interpreted in the United States to add requirements of “social visibility” and “particularity”, we will address this topic in part 3.1. Also, there has been a discussion about whether certain groups of individuals may fit in the “membership of a particular social group” concept, such as women and members of the LGTB community, so individuals in those groups may request asylum without difficulties.24

From this point of view, the narrow or broader interpretation of the concept of refugee is fundamental to provide rights to asylum seekers such as “the right to life, protection from torture and ill-treatment, the right to a nationality, the right to freedom of movement, the right to leave any country, including one's own, and to return to one's country, and the right not to be forcibly returned”. 25

B. Problems with the Interpretation of the Effects of the Principle of Non-RefoulementThere are several discussions about the effects of the principle of Non-Refoulement. One of them, according to the Department of Immigration & Multicultural & Indigenous Affairs of Australia (DIMIA),26 is whether Art. 33(1) “also includes within its ambit the right to be admitted at the frontier”.

DIMIA's paper stated that some commentators have answered this question in a negative form, establishing that the article 33(1) only applies to those “who have gained entry into the territory of the contracting State... but not refugees who seek entrance into this territory”. While other authors, such as Weiss and Goodwin-Gill, affirm the opposite.

Fernandez said that the practice of individual nations and the doctrine agree that the principle of Non-Refoulement also applies to those who are in the borders. Citing Goodwin-Gill, they state that the principle of Non-Refoulement “now encompasses both non-return and non-rejection”.27 In this regard, Lauterpach and Bethlehem, pointed out that even though the 1951 Convention and international law generally do not contain a right to asylum, nations are not free to reject at the frontier, and they must adopt measures to guarantee the principle of Non- Refoulement if they are not prepared to grant asylum, such as the removal to a safe third country or temporary protection or refuge.28

As we noted before, the view of the UNCHR is that the Principle of Non-Refoulement has extraterritorial effects, and therefore to return individuals to their country of origin before they can reach the frontier is considered a violation of Article 33(1) of the 1951 Convention. Thus, the UNCHR has said:

... any interpretation which construes the scope of Article 33(1) of the 1951 Convention as not extending to measures whereby a State, acting outside its territory, returns or otherwise transfers refugees to a country where they are at risk of persecution would be fundamentally inconsistent with the humanitarian object and purpose of the 1951 Convention and its 1967 Protocol.29

Even more, the UNCHR, using the travaux préparatoires of the 1951 Convention, recalls that the representative of the United States argued that:

[w]hether it was a question of closing the frontier to a refugee who asked admittance, or of turning him back after he had crossed the frontier, or even expelling him after he had been admitted to residence in the territory, the problem was more or less the same. Whatever the case might be, whether or not the refugee was in a regular position, he must not be turned back to a country where his life or freedom could be threatened. (Paragraph 30)

In spite of that, many nations tend to create instruments in order to reject individuals at the borders, with the purpose of being relief from the process to determine the status of refugee, and to avail themselves of the opportunity to return the person to his or her country of origin or to a third State.30 The said Instruments may consist of the requirement of visas, allegations of unfounded petitions that allow the rejection at the border without any examination of the claim, and the application of the principle of the country of first asylum.31

This discussion is not futile, if we acknowledge that since the 1980s there has been a mass exodus of people who arrive by sea to countries they consider safer. In the 1990s, the exodus came from Albania, Cuba and Haiti. Nowadays, the movement of people is coming from Somalia and Ethiopia to Australia by boat and from North Africa to Europe in the aftermath of the Libyan crisis. As the UNCHR noted “... irregular maritime movements are a reality in all regions of the world and raise a number of specific protection challenges, notably in the context of rescue at sea, stowaway incidents and maritime interception”.32

C. Problems with the Interpretation of the Scope of the Exceptions of the Non-Refoulement Principle

The 1951 Convention on Article 33 (2) consecrates two exceptions to the principle of Non-Refoulement: (i) in case of threat to the national security of the host country; and (ii) in case their proven criminal nature and record constitute a danger to the community.

The UNCHR has expressed, in the first case that “state practice and the Convention travaux preparations indicate that criminal offenses, without any specific national security implications, are not to be deemed threats to national security, and that national security exceptions to non-refoulement are not appropriate in local or isolated threats to law and order”. In the second case, the UNCHR has interpreted “particularly serious crime” as an exception of ultima ratio. Thus, the crime has to be very grave and “should only be considered when one or several convictions are symptomatic of the basically criminal, incorrigible nature of the person and where other measures, such as detention, assigned residence or resettlement in another country are not practical to prevent him or her from endangering the community”.33

However, these exceptions have been broadly interpreted by national authorities, and will be addressed below; as well as situations when, interpreting the scope of the exceptions, refugees, with a well-founded fear to persecution, have been expelled or returned to the countries where their life, freedom or personal integrity are in danger, under the premise that they are a threat to national security or constitute a danger to the community. Often, these exceptions are not applied as ultima ratio, or within a context that really threatens national security or endangers the community, as we will discuss later. Recently, voices have risen against the interpretation that allows a nation to consider anti-terrorism measures as been included within the exception brought by Article 33(2), so a person who might be deemed as a terrorist or who aided a group considered as a terrorist group by his or her nation (not necessarily affecting the national security of the country of asylum) may be subject to Refoulement.34

It is important, then, to apply a proportionality test between the consequences for the refugee if he or she is returned to his or her country of origin, the seriousness of the crime committed and the threat it will signify for the country of asylum.35

III. Asylum Policy of the United StatesThe UNHCR Asylum Trends 2012, reported the United States as the “largest single recipient of new asylum claims among 44 industrialized countries for the seventh consecutive year”, with 83,400 asylum applications, mainly from asylum seekers coming from China (24%), Mexico (17%) or El Salvador (7%).36

Asylum matters in the United States are regulated by the Immigration and Naturalization Act (INA) amended by several legislations either with the purpose to reduce immigration like the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, 1996, (IIRIRA), or with the purpose to combat terrorism such as the USA PATRIOT Act, EBSVERA,37 the HAS,38 the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 and the REAL ID Act of 2005.39 Administrative authorities and national courts are in charge of applying and interpreting the existing legislation in affirmative or defensive processes.

However, some of the policies and procedures of the United States in the subject of asylum and the application of the concept of Refugee and the principle of Non-Refoulement have been criticized by important international organizations on the subject such as the UNHCR and the ICHR, mainly because such policies and procedures in many instances are inconsistent with the 1951 Convention and its Protocol.40 For instance, the 2013 UNHCR regional operations profile - North America and the Caribbean, noting several flaws in the asylum policy of the United States, stated that:

In the United States of America... the detention of asylum-seekers arriving without papers or with false documents remains mandatory. Meanwhile, the application of membership of a “particular social group” as a ground for granting asylum remains inconsistent across the country, and the Government has not yet issued clarifying regulations...

...

... Significant constraints arise from laws which include broad criminal and terrorism-related bars that inhibit or prevent certain categories of refugees from being resettled in the country and forbid the granting of asylum to some individuals. The exemption process is lengthy and involves many government agencies. Legislation that may resolve these issues is not likely to pass in the present Congress in the near future...

Now, we will focus on the study of (i) the scope and interpretation of the concept of refugee, (ii) the extraterritorial application of the Principle of Non-Refoulement, and (iii) the exceptions to the Principle of Non-Refoulement and its interpretation under the U.S. asylum policy.

1. Scope and Interpretation of the Concept of Refugee under the Policy of the United StatesThe Immigration and Naturalization Act (INA) establishes the concept of refugee in the following terms:

(A) any person who is outside any country of such person's nationality or, in the case of a person having no nationality, is outside any country in which such person last habitually resided, and who is unable or unwilling to return to, and is unable or unwilling to avail himself or herself of the protection of, that country because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion...41

This concept of refugee was adopted from Article I of the 1951 Convention, which, as was referred earlier, must be interpreted in a broad fashion; otherwise such interpretation will be deemed a violation of international refugee law. Now, concerns about the approach taken by the United States policy have been an issue in study for several decades.42 Under the United States Asylum Law, the burden of proof is on asylum seekers, therefore he or she must prove his or her condition of refugee, with direct or circumstantial evidence that he or she has being persecuted on account of one of the statutory grounds established by INA (race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion). To sustain the burden of proof, the asylum seeker must show that the persecutor's motives were on account of one of the statutory grounds, which is very difficult because those motives are only in the mind of the persecutor.

An example of the narrow interpretation of the concept of refugee can be found in the case of Bueso-Avila v. Holder, 10-2760 (7th Cir. 2011)43 where the Court reasoned that to establish eligibility for asylum, an alien must have shown with direct or circumstantial evidence that the persecutor was motivated by one of the statutory grounds.44 However, it is important to point out that the Court recognized that “an individual may qualify for asylum if his or her persecutors have more than one motive as long as one of the motives is specified in the Immigration and Nationality Act”.

The interpretation of the Court in the above mentioned case is against the 1951 Convention, whose object and purpose is the protection of refugees and the guarantee of their fundamental rights and freedoms,45 considering it would deny protection to an individual, who proved he or she possesses a well-founded fear of persecution on one or more grounds of the 1951 Convention, under the premise that he or she also has to prove the motives behind the persecutor's actions.

Precisely, the UNCHR in an amicus curiae46 for the Bueso- Avila case, established that the analysis of the causal link between the fear of persecution and the convention ground must be done taking into account the object and purpose of the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol, decreeing that otherwise the United States may be in violation of its obligations under Article 33(1) of the 1951 Convention because of the denial of protection to refugees who are entitled to it.

From the point of view of the UNHCR, the fear of persecution can be caused by several Convention grounds or even for Convention grounds in conjunction with non-Convention grounds and those grounds do not have to be “the sole or even dominant cause”.47 This analysis must be done, according to the UNHCR, focusing on the reasons for the applicant's predicament; and even though the persecutor's motives are an important factor under United States law, the proof of those motives is difficult and therefore it should be enough to show circumstantial evidence.

This discussion, however, is not new. In 1984, the Stevic case showed how the United States court added requirements to the Convention Refugee definition. In that case, “the Court held that, in order to have deportation withheld, an alien must show that there is a ‘clear probability’ that such a threat exists”, that is, “whether it is more likely than not that the alien would be subject to persecution”.48 As in the cases shown above, the UNHCR at that moment also “submitted an amicus curiae brief to the US Supreme Court... arguing against the balance of probability or clear probability test as the criterion for the grant of asylum”.49 At the end, the Supreme Court rejected the clear probability standard to grant asylum.

Another example of this issue is shown by the UNHCR in its amicus curiae dated August 18 of 2010 in support of the petitioner Minta Del Carmen Rivera-Barrientos. In that document, the UNHCR pointed out that the BIA misinterpreted the meaning of “membership of a particular social group” when it imposed, as a requirement to identify a social group, that this last one has to have “social visibility” and “particularity”. According to the UNHCR, those requirements are inconsistent with the context, object and purpose of the 1951 Convention and its Protocol and with the UNHCR guidelines. In fact, “Significantly, the Board's imposition of the requirements of “social visibility” and “particularity” may result in refugees being erroneously denied international protection and subjected to Refoulement—return to a country where their “life or freedom would be threatened”—in violation of a fundamental obligation under the 1951 Convention”.50

These cases show that the immigration judges and authorities, who execute the migratory policy of the United States, usually make a narrow interpretation of the Convention Refugee definition and, with that, they overlook the risk that the applicants may face if returned to their countries of origin.

According to Aleinikoff, the authorities in the United States “tend to focus on whether the persecution feared is based on one of the five grounds in the refugee definition, despite the fact that no forms of persecution were intentionally excluded from the 1951 Convention at the drafting stage”. In practice, the United States is putting too much weight on the motivations of the persecutor, when the focus must be on the meaning of persecution, which requires that the harm in question be of a serious nature.51

On the other hand, the Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act for Defense, the Global War on Terror and Tsunami Relief, (Public Law 109 – 13) known as the Real ID Act of 2005, passed with the purpose to protect the United States against terrorists preventing they pose as refugees or asylum seekers to enter in the United States, amended section 208 (b) (1) of the INA to place new requirements to sustain the burden of proof on asylum applicants to establish they are in fact, refugees.52 Those new requirements imposed by the Real Id Act may be a serious issue for asylum seekers to assert their claims.

First, the Real ID Act requires the applicant to show “that race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion was or will be at least one central reason for persecuting the applicant”.

“At least one central reason” is a new standard created by the Real ID Act, stringent than the concept of “mixed motives” 53 for the persecution of an alien used in precedent case law.54 The concept of “mixed motives” allowed judges to grant asylum when one of the motives for the persecution is one of the grounds established by INA. The new standard of “central reason” only allows judges to grant asylum if one of the grounds established by INA is a central motive for the persecution.55 Therefore, asylum seekers, who have been subject to persecution on statutory grounds and non-statutory grounds, may be deported because the statutory ground was not the central reason of the persecutor.56

Second, the Real ID Act requires, when evidence is based only in the testimony of the applicant without further corroboration, that the applicant “satisfies the trier of fact that the applicant's testimony is credible, is persuasive, and refers to specific facts sufficient to demonstrate that the applicant is a refugee”. This means that Real ID Act did not create a presumption of credibility, (even though there is a rebuttable presumption on appeal, if there is no express adverse credibility determination), therefore a court, when analyzing the claim, would weight all relevant factors around the testimonies and may be able to deny the petition if he or she finds “any inaccuracies or falsehoods in such statements, without regard to whether an inconsistency, inaccuracy or falsehood goes to the heart of an applicant's claim”.57

The issue here is that inaccuracies or falsehoods in an applicant's testimony may be due to cultural differences or fear,58 and not all of them might be regarding the applicant's status of refugee, but, for instance, to the applicant's life in the United States. Nonetheless, according to the Real ID Act, even the latest inconsistencies are enough to prevent a legitimate refugee to seek protection in the United States.59

Third, if the testimony of the applicant does not satisfy the trier of fact, then additional evidence “that corroborates otherwise credible testimony” must be provided.60 Thus, the Real ID Act created a burden of corroboration beyond the applicant's own testimony that may be too hard, as the constant in asylum applications cases is the lack of evidence. Asylum application must be seen in the light of the circumstances in which refugees left their countries of origin or residence, since asylum seekers may have a valid justification for not being able to produce the evidence as require by law, for instance because they left in such a hurry that they did not have opportunity to collect evidence or they lost the one they have, or they had to use false documentation in order to abandon their countries. Also, asylum seekers, who have no representation, or who have been detained by U.S. authorities, stand few chances to produce the evidence necessary to support their claims.61

As a consequence, an individual with a well-founded fear of persecution on account race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion, may be subject to refoulement if he or she is not able to show that (i) the central reason the persecutor had for threaten applicant's life or integrity was one of the statutory grounds, (ii) his or her testimony is credible, persuasive, and refers to specific facts sufficient to demonstrate that the applicant is a refugee, (iii) evidence, in case the adjudicator consider his or her testimony is not enough.

Each of those requirements implies a burden, in many cases, hard to comply for asylum seekers, as explained before, and reduces the scope of the concept of refugee, which must be interpreted in the widest possible manner, resulting in a violation of the 1951 Convention and the principle of Non-Refoulement.

2. Extraterritorial application of the Principle of Non-Refoulement and the Policy of the United States: Interception at SeaSince the 1980's, the United States has had a policy of interception at sea to prevent irregular immigration, especially for Haitians and Cubans:62 that is the ongoing policy today.63 The issue of concern here is that interception at sea is managed so it may include returning people with a valid claim of “well-founded fear of persecution,” back to countries where their life or freedom are in danger.64 The UNCHR has said in regard to this issue that the principle of Non-Refoulement has extraterritorial application, which is clear from the text of the provision itself [article 33], which states a simple prohibition: “No Contracting State shall expel or return (“refouler”) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his [or her] life or freedom would be threatened...”.65 Therefore, to return refugees intercepted at sea is against the object and purpose of the 1951 Convention.66

However, in the well-known case Sale v. Haitian Centers Council 509 U.S. 155(1993), the U.S. Supreme Court held that the principle of Non-Refoulement did not have an extraterritorial application. It was deemed to be applied only within the territory of the Contracting nations, which means interception at sea does not amount to a violation of Article 33 of the 1951 Convention or INA itself.67

Under that precedent, the United States maintains the policy of interdicting individuals at sea and returning them to their country of origin unless they can claim they are refugees.68 “The Coast Guard transfers those it finds to have a credible fear of return to the U.S. naval base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where the Department of Homeland Security officers interview them”.69 In spite of that, as pointed out by Bill Frelick, “in the case of the Haitians, only a tiny number of Haitians interdicted on the high seas have ever had asylum claims heard. Upon interdiction, U.S. officials provide no information to the people taken aboard U.S. Coast Guard cutters about their right to seek protection”.70

This Policy of the United States is now contained in the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, 1996, (IIRIRA), which modified the Immigration and Naturalization Act. The IIRIRA established a process for the expedited removal71 of aliens entering the country by fraudulent means, misrepresentation, or without proper travel documents, which includes aliens interdicted at sea and stowaways. Section 302 of the IIRIRA established it when explaining the concept of an alien treated as an applicant for admission:

... An alien present in the United States who has not been admitted or who arrives in the United States (whether or not at a designated port of arrival and including an alien who is brought to the United States after having been interdicted in international or United States waters) shall be deemed for purposes of this Act an applicant for admission. (The underline is mine)

(2) STOWAWAYS.-An arriving alien who is a stowaway is not eligible to apply for admission or to be admitted and shall be ordered removed upon inspection by an immigration officer. Upon such inspection if the alien indicates an intention to apply for asylum under section 208 or a fear of persecution, the officer shall refer the alien for an interview under subsection (b)(1)(B). A stowaway may apply for asylum only if the stowaway is found to have a credible fear of persecution under subsection (b)(1)(B). In no case may a stowaway be considered an applicant for admission or eligible for a hearing under section 240.72

On the other hand, the IIRIRA, amending INA section 235 (b) (1) (B) (iii) (I), mandates that an alien who is requesting asylum may be removed without further review if the officer determines that he or she does not have a credible fear of persecution. The officer should determine such credible fear of persecution only with the statements made by the alien and the facts that are known to the officer.73

The decision of the officer, supported by a written record, is subject to review under the following conditions:74

- 1)

The alien must request the review.

- 2)

The alien must be heard by the immigration judge (the hearing may be conducted personally, by telephone or video).

- 3)

The review shall be concluded within 24hours and no later than 7 days.

Finally, the IIRIRA orders mandatory detention75 for asylum seekers pending a final determination of credible fear of persecution and, if found not to have such a fear, until removal.76

The analysis of these provisions of the IIRIRA leads to the belief that, under the circumstances of interception at sea or even in cases where refugees arrive at the borders, the principle of Non-Refoulement might be easily violated. Asylum seekers, who were caught at sea, may be too scared and too confused to exercise their rights; they probably do not know they are entitled to make asylum claims before the Officer of the Coast Guard who made the interception, and even less likely to request a review under United States Law, adding that they are detained while the procedures are carried out by the authorities.77

Also, to make an informed decision about a credible claim of fear of persecution based only on the statements of the asylum seekers, and one's own knowledge about the topic, may lead to erroneous decisions. It is necessary to take into account the circumstances in which the individuals left their countries, as we stated before. In many cases, they do not have proof of their claims, for example, because they lost their documents on their way out of the country. Furthermore, the time allocated for the review is too short, and due process concerns may arise at this stage.78

As a consequence, the expedited removal proceeding created by the IIRIRA increases the chances of refoulement for bona fide asylum seekers, in contradiction with the 1951 Convention. The situation gets worse if we notice that the IIRIRA, amending section 212(a) (8 U.S.C. 1182 (a), declares as “inadmissible” aliens, who previously were removed, for a period of 5 years since the date of their removal. This means that any alien subjected to expedited removal (including those with a well-founded fear to persecution who was mistakenly remove under these provision of the IIRIRA) will be barred to re-enter the United States for a period of 5 years. Additionally, the IIRIRA impose a one year deadline for filing applications for asylum protection which affects the opportunities for refugees to request asylum and expose them to refoulement even if they have a legitimate asylum claim.79

The impact of the IIRIRA is shown in the number of refugee arrivals and asylum applications in the United States. The Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2011, of the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Office of Immigration Statistics, reveals that between 1980 and 1996 the number of refugees arrivals ranged between 207,116 in 1980 (hightest peak) and 61,218 in 1983 (lowest peak) with an average of 101, 486 refugees arriving to the United States. Those numbers started to drop after 1996 (year in which IIRIRA was passed) and after 2001 the situation got worse, with refugee arrivals reaching its lowest point in 2002 with 26,788. Still, its highest peak was in 2009 with 74,602, far away from the highest peak in 1980.

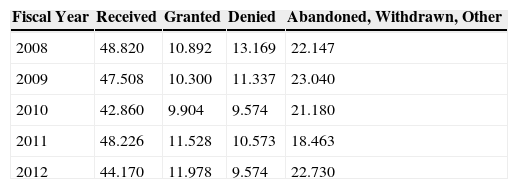

In his analysis of the IIRIRA, Frelick said that while from 1992 thorugh 1996 the yearly average of asylum applicants to the INS was 106,200; between 1997 thorugh 2001, the yearly average number of asylum applicants dropped 56 percent, to 46,900 applications. After September 11, 2001, the asylum applications dropped from 100,270 in 2002 to 73,780 in 2003. By 2005 the number was 48,770. More recently, as shown in Table 1, between 2008 and 2012, the yearly average number of asylum applicants is 46,316, keeping the tendency showed since 1997.

United States Asylum Statistics.

| Fiscal Year | Received | Granted | Denied | Abandoned, Withdrawn, Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 48.820 | 10.892 | 13.169 | 22.147 |

| 2009 | 47.508 | 10.300 | 11.337 | 23.040 |

| 2010 | 42.860 | 9.904 | 9.574 | 21.180 |

| 2011 | 48.226 | 11.528 | 10.573 | 18.463 |

| 2012 | 44.170 | 11.978 | 9.574 | 22.730 |

Source: Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR),U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), FY 2012 Statistical Year Book.

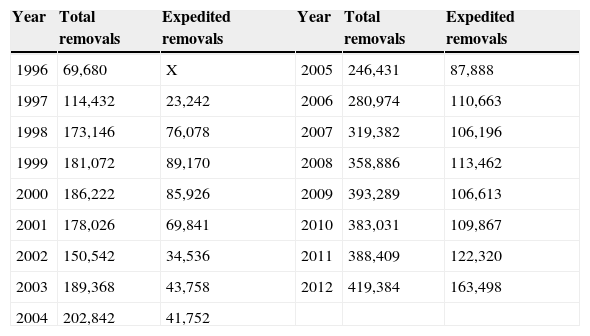

Another impact of the IIRIRA is shown in expedited removal process that has brought as a consequence the deportation of thousands of aliens each year, including asylum seekers.80 According to the report of the DHS on immigration enforcement actions (2004), the number of expedited removals in 1997 was of 23,242. Those numbers increased between 1998 and 2001. After 2002, the numbers decreased. The report attributed this reduction of expedited removals to the “tightened border security” implemented after the September 11 attacks. However, expedited removals increased again after 2005, reaching its highest peak since 1999, in 2012 with 163,498, as shown in Table 2.

Trends in Total and Expedited Removals: 1994 to 2012.

| Year | Total removals | Expedited removals | Year | Total removals | Expedited removals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 69,680 | X | 2005 | 246,431 | 87,888 |

| 1997 | 114,432 | 23,242 | 2006 | 280,974 | 110,663 |

| 1998 | 173,146 | 76,078 | 2007 | 319,382 | 106,196 |

| 1999 | 181,072 | 89,170 | 2008 | 358,886 | 113,462 |

| 2000 | 186,222 | 85,926 | 2009 | 393,289 | 106,613 |

| 2001 | 178,026 | 69,841 | 2010 | 383,031 | 109,867 |

| 2002 | 150,542 | 34,536 | 2011 | 388,409 | 122,320 |

| 2003 | 189,368 | 43,758 | 2012 | 419,384 | 163,498 |

| 2004 | 202,842 | 41,752 |

Source: Reports of the DHS on immigration enforcerment actions,FY 2004, 2009 and 2012.

Regarding to asylum seekers in expedited removal process, the US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) found that “there was frequent failure on the part of CBP officers to provide required information to aliens during Secondary Inspection interview and occasional failures to refer eligible aliens for Credible Fear interviews when they expressed a fear of returning to their home countries”. They also found “number of inconsistencies between their observations and the official records prepared by the investigating officers”, and “attempts by CBP officers to coerce aliens to retract their fear claim and withdraw their applications for admission”.81 According to Donald Kerwin, the USCIRF reported “that one of every six migrants subject to this process who expressed a fear of return was summarily removed in contravention of the law”.

3. Exceptions to the Principle of Non-Refoulement and its InterpretationAnother issue on this topic is the interpretation and application of the exceptions to the obligation of Non-Refoulement under article 33(2) of the 1951 Convention, which establishes that:

The benefit of the present provision may not, however, be claimed by a refugee whom there are reasonable grounds for regarding as a danger to the security of the country in which he is, or who, having been convicted by a final judgment of a particularly serious crime, constitutes a danger to the community of that country.

These exceptions have been reproduced under INA § 208 (b)(2), which establishes that an alien cannot apply for asylum if, (i) the alien ordered, incited, assisted, or otherwise participated in the persecution of any person on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion; (ii) the alien, having been convicted by a final judgment of a particularly serious crime, constitutes a danger to the community of the United States; (iii) there are serious reasons for believing that the alien has committed a serious non - political crime outside the United States prior to the arrival of the alien in the United States; (iv) there are reasonable grounds for regarding the alien as a danger to the security of the United States; (v) the alien is engaged in terrorist activity within the meaning of INA § 212(a)(3)(B)(i) or § 237(a)(4)(B); and finally, (vi) the alien was firmly resettled in another country prior to arriving in the United States.

The courts in the United States use these provisions to bar the applicants from their asylum claims, sometimes making a broad interpretation of it. For instance, what constitutes “a particular serious crime” is today subject of an expanded definition and the list of crimes that qualify as aggravated felonies for purposes of deportation includes what are in fact misdemeanors under criminal law. In addition, if a refugee adjusts his or her status to that of permanent resident, he or she loses his or her protection as refugee and can be deported for even minor crimes.82

In N-A-M v. Holder, Nos. 07-9580 and 08-9527 (10th Cir, 2009), N-A-M, a “preoperative transsexual (male-to-female) from El Salvador was subjected to multiple instances of persecution due to her transgendered status, and fled to the United States in 2004, entering without inspection. In June 2005, N-A-M was convicted of felony menacing”. (p. 2). The Immigration Judge found that although N-A-M had a valid asylum claim, the U.S.C. § 1231(b)(3)(b)(ii) provides an exception to withholding of removal the conviction of the alien for a particularly serious crime and therefore she must be subject to removal. This decision was affirmed by the BIA and the Court of Appeals. The Court reasoned that section 1231 says that the exception to withholding of removal is effective if “the alien, having been convicted by a final judgment of a particularly serious crime is a danger to the community of the United States;. .” however, that section does not require a separate “danger to the community” assessment. Once it is determined that the alien committed a serious crime, the authorities do not have the obligation to study if the alien is a danger to the community.

According to the UNHCR, the interpretation given by the court in this case was erroneous. First, because the exceptions to the obligation of non-Refoulement “must be constructed in the most restrictive fashion”; and second, because Article 33(2) requires two findings: the conviction of the person seeking refugee protection by a final judgment of a “particularly serious crime” and “an individualized assessment of whether the refugee does, in fact, constitute a future “danger to the community.” It is this second prong—whether the refugee poses a future danger to the community—that is the essential inquiry in this analysis”.

In this particular case, the court did not determine if the defendant was a danger to the community or not. The court, based on the precedent set out in the case Al-Salehi v. INS, limited its analysis to determine if the applicant was or was not convicted of a serious crime. From the point of view of the UNHCR this interpretation is “contrary to United States obligations under international law” and “contrary to the spirit, purpose and requirements of Article 33(2)”.

On the other hand, after the event of September 11, 2001, new legislation was enacted as well, limiting the rights of asylum seekers, in particular, the USA PATRIOT Act and the REAL ID Act of 2005.83

The USA PATRIOT Act or “The Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act” was signed into law by President Bush on October 26, 2001, with the purpose to combat terrorism in the United States. This Act amended several laws, among them, immigration laws, particularly, INA § 212, establishing that aliens involved in terrorist activities are ineligible to receive visas and to be admitted to the United States.

Under the Patriot Act, “the term ‘terrorist activity’ means any activity which is unlawful under the laws of the place where it is committed (or which, if it had been committed in the United States, would be unlawful under the laws of the United States or any State)…” and it considers that a person is engaged in terrorism activities, among others, if he or she commits “an act that the actor knows, or reasonably should know, affords material support, including a safe house, transportation, communications, funds, transfer of funds or other material financial benefit, false documentation or identification, weapons (including chemical, biological, or radiological), explosives, or training” for the commission of a terrorist activity, or to an individual or terrorist organization.

These provisions of the Patriot Act are the most controversial in relation to the rights of asylum seekers because the meaning of “terrorism activities” and “terrorism organization” 84 is so broad that any activity or any organization might be consider as terrorism.85 Likewise, the interpretation of “material support” in the sentence “engaged in terrorism activities” is subject to criticism because whether the support is material enough to be consider as a sponsor of terrorism activities, individual or terrorism organization, would be determined under a subjective and broad manner. For instance, In Matter of S-K, a case involving a Baptist woman form the Chin minority of Burma (Myanmar), the immigration judge and the BIA accepted that S-K had a credible fear of persecution and even though she provided modest material support to the Chin National From, a group engaged in armed resistance to a government the United States did not support, that support did not represent a threat to the security of the United States. However, the Court reasoned that because the U.S. Patriot Act of 2001 and the Real ID Act of 2005 define “terrorism organization” so broadly, the petitioner fell into the scope of engaged in terrorism activities and therefore the asylum should be deny.86

About the term “material support”, the UNCHR has said that it must be interpreted in accordance to the international obligations the United States acquired with the ratification of the 1967 Protocol. For the UNCHR, denial of withholding of removal purports a violation of the principle of non-refoulement, if a person, who provided support to a terrorist organization under the terms of INA, does not constitute a danger for the security of the United States, or at least there are no reasonable grounds to consider that person a danger.

The exception brought by article 33(2) must be interpreted in the sense that the refugee represents a threat to the national security of the host country; therefore, a breach of Article 33 may be possible when applying this exception considering that “an individual who has provided support to an individual or an organization that has engaged in “terrorist activity” as broadly defined by the INA does not necessarily pose a danger to the security of the United States”.87

Another critic of the “material support” term is that it does not distinguish refugees who provide support under duress. To this regard, The Freedom House has said that:

The immigration provisions of the PATRIOT Act have also affected some refugees seeking asylum from countries associated with terrorism. Under current law, asylum-seeking immigrants may be detained or deported if they have ever provided “material support” to terrorist organizations. However, the law makes no distinction between voluntary and coerced support. Some refugees seeking asylum in the United States —including those from Colombia, Burma, and other nations— have been denied entry because the terrorist groups in their home countries extorted money from them.88

Because immigrations laws have had an unintended effect in refugees and asylum seekers, the Congress of the United States gave the Secretary of Homeland Security and the Secretary of State, in consultation with the attorney general the faculty to grant waivers under its discretion to create a way to except refugees that otherwise will fit in the “material support” bar. However, according to Human Rights First,89 waivers are only granted “after two levels of often duplicative adjudications, first on the merits of the application for asylum or other status, and then on whether or not to grant a waiver”. As a result, the process is long, with almost no information for refugees about their cases and with no opportunity to appeal any decision that may affect them. Other cases, such as victims of terrorism groups, for instance, children recruited by force, are not even being considered for a waiver because the exception was created only for the “material support” bar.

All these provisions of the US PATRIOT ACT have affected refugees and asylum seekers directly. Even though, there are not statistics lead by any entity of the United States government to show how many cases has been denied or delayed due to the “terrorism” related bars,90Human Rights First, a non-governmental organization, stated that the number of affected refugees is around 18,000. Also, it pointed out that “over 7,500 cases pending before the Department of Homeland Security are on indefinite hold based on some actual or perceived issue relating to the immigration law's ‘terrorism’ -related provisions”.91 In relation to this same topic, the Refugee Council USA, in March 2007, estimated that 15,310 cases were on hold due to the “material support” bar, affecting minority groups of refugees.92 On the other hand, the 2011 Yearbook of Statistics from DHS indicates that refugee's admissions dropped after 9/11 attacks and the pass of the US PATRIOT Act. Thus, while the average of refugee's arrivals between 1980 and 2001 was 95,362, the average of refugee's arrivals between 2002 and 2011 was 51,535, which means a decrease of more or less half of refugee's admissions in the United States.

From this perspective, we can conclude that many refugees and asylum seekers, with a legitimate claim of fear of persecution, are declared inadmissible to the United States and therefore expelled to countries where their life or personal integrity is threated due to the broad provisions of the US PATRIOT Act.

IV. International Responsibility of the United StatesThe fundamental principle of the international responsibility of the states is that “every internationally wrongful act of State entails the international responsibility of that State”93 and the source of the international responsibility of a state is a “conduct consisting of an action or omission” that encompass two elements: (i) “is attributable to the State under international law”; and (ii) “constitutes a breach of an international obligation of the State”.94

In this case, without doubt the United States has been, by a conduct consisting of an action attributable to the United States under international law, in violation of the principle of Non-Refoulement, which is a violation of international treaties: the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol, and therefore entails its international responsibility.

With regard to the first element, we affirm the conduct is attributable to the United States under international law because the conduct is represented in the pass of legislation that is against the principle of Non-Refoulement, judgments delivery by courts that limit the interpretation and application of the aforesaid principle, and acts of administrative authorities on the high seas, borders, airports and ports that amount as a violation of the principle of non-refoulement.95

The second element is clearer. The violation of the principle of Non-Refoulement constitutes a breach of the international obligation set up in article 33 of the 1951 convention of not “expel or return (‘refouler’) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion”. International obligation that the United States bound to comply when ratified the 1967 Protocol.

The consequences of the violation of the principle of Non-Refoulement however are less clear. The 1951 Convention, article 38, established that disputes arising from the interpretation or application of the Convention that cannot be settled by other means will be solved by the International Court of Justice (ICJ). The 1967 Protocol has a similar provision in article IV. The United States did not make a reservation of that provision; therefore in theory any country may take the United States to the ICJ to address the issue of the interpretation and application of the Convention. In practice, no State has been willing to do it.

Likewise, there are other international treaties that establish the principle of Non-Refoulement, such as the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).96 The United States is a party in both treaties. Also, both treaties provide for a method to solve disputes relating to their interpretation and application. The CAT resorts to negotiations, arbitration and finally, if those methods do not offer solution, opens the door for the claim to be heard by the ICJ. The ICCPR created the Committee on Human Rights, which has competence to hear claims between nations regarding the breach of the Covenant. Also, the Committee may hear individual claims against nations and report on those claims; however those reports are not binding upon nations.

About the CAT, the United States made several reservations. Particularly, the United States declared “that it does not consider itself bound by Articles 30(1), but reserves the right specifically to agree to follow this or any other procedure for arbitration in a particular case”. That means, that the United States cannot be taken to the ICJ, but it may agree to arbitrate particular cases. Nonetheless, it recognizes the competence of the Committee against torture under the condition of reciprocity, but once again those reports are not binding upon nations.

V. ConclusionsInterpretation of the principle of Non-Refoulement and the fundamental concept of refugee within the U.S. asylum policy is the subject of many concerns. In the United States, administrative authorities and national courts often make narrow or broader interpretations of those concepts that, in many cases, are used to bar an individual with a legitimate claim of fear of persecution from the protection granted by the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol.

The principle of Non-Refoulement, a fundamental key of international refugee law, clearly prohibits nations from returning refugees or asylum seekers to countries where their lives or freedom may be threatened. The United States asylum policy, in many aspects, is not consistent with that principle.

United States case law shows that the term “refugee”, as defined by the 1951 Convention, is interpreted under narrow parameters, adding requirements that the Convention did not foresee, such as the “social visibility” and “particularity” criterion to determine if a person has been persecuted on account of “membership in a particular social group.” As a result, a true refugee under the concept of the 1951 Convention may be object of Refoulement in the United States.

On the other hand, interdiction in the high seas of individuals who may have a well-founded fear of persecution, and the inclusion within the immigration laws of expedited removal procedures without review, legal assistance and detention, put the principle of Non-Refoulement under risk, if considered that refugees and asylum seekers do not really have the opportunity to present their claims within a fair scenario. Also, the broad interpretation of the exceptions to the principle of non-refoulement and the expansion of other bars related to terrorism in order to deny asylum or withholding of removal, make the probability of refoulement more likely.

Even though, the policy behind the immigrations laws is to prevent irregular immigration and to combat terrorism activities, which is very important, it is also important to balance the risk the national security faces against the risk of death or ill treatment a refugee may suffer if returned to the country he or she fled. Thus, the interpretation and application of immigration laws by the U.S. judicial and administrative authorities must be done in accordance with the international obligations and the purpose and object of the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol, in particular, its article 33. Otherwise the humanitarian protection that refugees are entitled of will be reduced dramatically.

VI. BibliographyAleinikoff, Alexander, “The Meaning of “Persecution” in United States Asylum Law. “International Journal of Refugee Law, United Kingdom, volume 3, issue 1 of 1991.

Ardis, Martin W. (ed.), REAL ID Act of 2005 and Its Interpretation, New York, Nova Science Publisher, 2005.

Board Of Immigration Appeals, Matter of S-P-, 21 I&N Dec. 486, 1996.

________, Alexander, Matter of J-B-N- & S-M-, 24 I&N Dec. 208, 2007.

Cohen, Roberta, “Legal Grounds for Protection of North Korean Refugees”, http://www.brookings.edu/research/opinions/2010/09/north-korea-human-rights-cohen.

Department Of Immigration & Multicultural & Indigenous Affairs Of Australia (DIMIA), “The Principle of Non-Refoulement (Article 33) An Australian Perspective”, http://www.immi.gov.au/media/publications/refugee/convention2002/06_refoulement.pdf.

Department Of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Statistics, 2011.

Dzubow, Jason, “The Refugee Protection Act and the “Central Reason” for Persecution”, May 10, 2010, http://www.asylumist.com/2010/05/10/the-refugee-protection-act-and-the-central-reason-for-persecution/.

Farmer, Alice, “Non-Refoulement and Jus Cogens: Limiting Anti-Terror Measures That Threaten Refugee Protection”, Georgetown Immigration Law Journal, volume 23, issue 1, 2008.

Fernández Arribas, Gloria, Asilo y refugio en la Unión Europea, Granada, Comares, 2007.

Fletcher, Aubra, “The REAL ID Act: Furthering Gender Bias in U.S. Asylum Law”, vol. 21, issue 1, Berkeley, Berkeley Journal of Gender Law & Justice, 2013.

Freedom House, Today's American: How Free? - The civil liberties implications of counterterrorism policies, May 2 2008, http://www.refworld.org/docid/491013161d.html.

Frelick, Bill, “The U.S. Asylum and Refugee Policy. The ‘Culture of No’, in Schultz, William, The Future of Human Rights. U.S. Policy for a New Era, Pennsylvania, University of Press, 2008.

García, Michael et al., “Immigration: Analysis of the Major Provisions of the Real ID Act of 2005”, Report for Congress, 2005

Goodwin-Gill, Guy and Macadam, Jane, The Refugee in International Law, 3rd edition, New York, Oxford, 2007.

Hathaway, James, The Rights of Refugees under International Law, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2005.

Human Rights First, “The impact of the Immigration Law's ‘Terrorism Bars’ on Asylum Seekers and Refugees in the United States”, 2009.

Human Rights Watch, “Human Rights Watch World Report 2002-United States”, 17 January 2002, http://www.refworld.org/docid/3c4c3b144.html.

Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, 1996.

Insignares, Silvana and Llain, Shirley, “Migración internacional y conflicto: Un análisis desde la política norteamericana y colombiana”, Revista de Derecho, Universidad del Norte, Edición Especial, 2012.

Kerwin, Donald, “US Refugee Protection Policy Ten Years after 9/11”, in Shoba Sivaprasad Wadhia (ed.), The 9/11 Effect and Its Legacy on US Immigration Laws, State College, Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania State University, 2011.

Kjærum, Morten, “Refugee Protection between State Interests and Human Rights: Where Is Europe Heading?”, Human Rights Quarterly, vol. 24, no. 2, may 2002.

Lauterpacht, Elihu and Bethlehem, Daniel, The Scope and Content of the Principle of Non-Refoulement: Opinion, June 2003, Cambridge University Press http://www.refworld.org/docid/470a33af0.html.

Legomsky, Stephen, Immigration and Refugee Law and Policy, 4th edition, New York, Foundation Press, 2005.

Mariño Menéndez, Fernando, “La Singularidad del Asilo Territorial en el Ordenamiento Internacional y su Desarrollo Regional en el Derecho Europeo”, in Mariño Menéndez, Fernando (ed.), El derecho internacional en los albores del siglo XXI. Homenaje al profesor Juan Manuel Castro-Rial Canosa, Madrid, Trotta, 2002.

Newmark, Robert, “Non-Refoulement Run Afoul: The Questionable Legality of Extraterritorial Repatriation Programs”, Washington University Law Review, vol. 71, issue 3, 1993.

Pistone, Michele And Schrag, Philip, “The New Asylum Rule: Improved but Still Unfair”, Georgetown Immigration Law Journal, Washington D. C, vol 16, issue 1, 2001.

Sautman, Barry, “The Meaning of “Well-Founded Fear of persecution in the United States Asylum Law and in international Law”, Fordham International Law Journal, Berkeley, volume 9, issue 3, 1985.

Silenzi Cianciarulo, Marisa, “Terrorism and Asylum Seekers: why the real ID Act is a False Promise”, Harvard Journal on Legislation, vol. 43, 2006.

Sridharan, Swetha, “Material Support to Terrorism — Consequences for Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the United States”, Migration Information Source Online Journal, January, 2008, http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/material-support-terrorism-%E2%80%94-consequences-refugees-and-asylum-seekers-united-states.

Stoyanova, Vladislava, “The Principle of Non-Refoulement and the Right of Asylum Seekers to Enter State Territory”, Interdisciplinary Journal of Human Rights Law, vol 3, issue 1, 2008-2009.

The Real ID Act, the United States, 2005.

The Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act (USA PATRIOT Act), the United States, 2001.

The Redress Trust (Redress) And The Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association (ILPA), “The Seminar “Non-Refoulement Under Threat”, Matrix Chambers, London, 16 May 2006, http://www.redress.org/downloads/country-reports/Non-refoulementUnderThreat.pdf.

Trevisanut, Seline, “The Principle of Non-Refoulement at Sea and the Effectiveness of Asylum Protection”, Max Planck Yearbook of United Nations Law, Leiden, volume 12, 2008.

UN General Assembly, Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, 28 July 1951, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 189.

Trevisanut, Seline, Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, 31 January 1967, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 606.

UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “Fact Sheet No. 20, Human Rights and Refugees”, July 1993, http://www.refworld.org/docid/4794773f0.html.

United Nations, “A/RES/51/75”, 12 February 1997, para. 3, http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/51/ares51-75.htm.

United Nations, “A/RES/52/132” 12 December 1997, para 12, http://www.unhchr.ch/Huridocda/Huridoca.nsf/%28Symbol%29/A.RES.52.132. En?Opendocument.

United Nations High Commissioner For Refugees, “UNHCR Note on the Principle of Non-Refoulement”, november 1997, http://www.refworld.org/docid/438c6d972.html.

United Nations High Commissioner For Refugees, “Amicus Curiae in Support of the Petitioner, NO. 09-2878 (A098-962-408), case Bueso-Avila v. Holder”. 9 of November 2010, http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/4cdbbd052.html.

United Nations High Commissioner For Refugees, UNHCR intervention before the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in the case of Thawng Vung Thang v. Gonzales, Attorney General, 9 February 2007, Case No. 06-60646, http://www.refworld.org/docid/4891cb312.html.

United Nations High Commissioner For Refugees, “Advisory Opinion on the Extraterritorial Application of Non-Refoulement Obligations under the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol”, 26 January 2007, Paragraph 29, http://www.refworld.org/docid/45f17a1a4.html.

United Nations High Commissioner For Refugees, “Rescue at Sea, Stowaways and Maritime Interception: Selected Reference Materials”, 2nd Edition, December 2011, http://www.refworld.org/docid/4ee087492.html.

United Nations High Commissioner For Refugees, “Refugee Protection: A Guide to International Refugee Law”, 1 December 2001, http://www.refworld.org/docid/3cd6a8444.html.

United Nations High Commissioner For Refugees, “Guidelines on International Protection No. 2: “Membership of a Particular Social Group” Within the Context of Article 1A(2) of the 1951 Convention and/or its 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees”, 7 May 2002, HCR/GIP/02/02, http://www.refworld.org/docid/3d36f23f4.html.

United Nations High Commissioner For Refugees, “UNHCR Asylum Trends 2012: Levels and Trends in Industrialized Countries”, 21 March 2013, http://www.refworld.org/docid/514ad4e02.html.

United States Committee For Refugees And Immigrants, “World Refugee Survey 2009 - United States”, 17 June 2009, http://www.refworld.org/docid/4a40d2b580.html.

United States Commission On International Religious Freedom, Annual Report, May 1, 2006, at 69 http://www.uscirf.gov/images/AR2006/2006annualrpt.pdf.

United States Court of Appeal, Fourth Circuit, Quinteros-Mendoza v. Holder, 556 F.3d 159, 2009.

United States Court of Appeal, Tenth Circuit, N-A-M V. Holder, Nos. 07-9580 and 08-9527, 2009.

United States Court of Appeal, Second Circuit, Xiu Xia Lin v. Mukasey, 534 F.3d 162, 2008.

United States Court of Appeal, Seventh Circuit, Mohideen v. Gonzales, 416 F. 3d 567, 570, 2005.

United States Court of Appeal, Seventh Circuit, Shaikh v. Holder, 702 F. 3d 897, 2012.

United States Supreme Court, Sale V. Haitian Centers Council, 509 U.S. 155 (1993).

Worster, William Thomas, “The Evolving Definition of the Refugee in Contemporary International Law”, Berkeley Journal of International Law (BJIL), vol. 30, no. 1, 2012.

This convention has been ratified as November 2013 by 145 countries.

1967 Protocol has been ratified as November 2013 by 146 countries.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “UNHCR Note on the Principle of Non-Refoulement”, November 1997, http://www.refworld.org/docid/438c6d972.html. Cfr. Fernandez Arribas, Gloria, Asilo y refugio en la Unión Europea. Granada, España, Comares, 2007. p. 155.

Goodwin-Gill summarized the principle in the following terms: “no refuge should be returned to any country where he or she is likely to face persecution, other ill-treatment, or torture”. Cfr. Goodwin-gill, Guy and Macadam, Jane, The Refugee in International Law, 3rd edition, New York, Oxford, 2007, p. 600.

Article 33(2) establishes that “The benefit of the present provision may not, however, be claimed by a refugee whom there are reasonable grounds for regarding as a danger to the security of the country in which he is, or who, having been convicted by a final judgment of a particularly serious crime, constitutes a danger to the community of that country”.

According to the UNCHR, “An estimated 479,300 asylum applications were registered in the 44 industrialized countries in 2012, an increase of 8 per cent over 2011. This is the second highest level in the past decade. Only in 2003 were more asylum claims recorded (505,000)”. The first country to receive more asylum claims in 2012 was the United States followed by Germany, France, Sweden, and United Kingdom. Cfr. United Nations High Commissioner For Refugees, “UNHCR Asylum Trends 2012: Levels and Trends in Industrialized Countries”, 21 March 2013, http://www.refworld.org/docid/514ad4e02.html.

However, the obligation of Non-refoulement has also been included in several other human rights instruments, among which we can count the 1984 UN Convention against Torture (Art. 3); the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Art. 7) (It does not say it expressly, but it has been interpreted as an implied prohibition of Non-Refoulement); the 1949 Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Times of War (Art. 45); the 1969 OAU Convention governing the specific aspects of refugee problems in Africa (Art. II(3)); the 1969 American Convention on Human Rights (Art. 22(8)); the 1981 African Charter of Human and Peoples’ rights (Art. 12(3)) and the 1950 European Convention on Human Rights (Art. 3). (The 2004 Qualification Directive prohibits the return to death penalty, execution, torture or inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment in the applicant's country of origin.) Goodwin-Gill, op. cit., pp. 208-211.

See Goodwin-Gill, op. cit., above note 3, p. 345-355; see the content of the Principle of Non-Refoulement in customary international law in Lauterpacht, Elihu and Bethlehem, Daniel. The Scope and Content of the Principle of Non-Refoulement: Opinion, Cambridge University Press, June 2003, p. 93. http://www.refworld.org/docid/470a33af0.html. For an opposite view see: Hathaway, James, The Rights of Refugees under International Law, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2005, p. 363.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees, 1997, op. cit.

Fernandez Arribas, op. cit.

United Nations, “A/RES/51/75”, 12 February 1997, para. 3, http://www.un.org/docu ments/ga/res/51/ares51-75.htm ; and United Nations “A/RES/52/132” 12 December 1997, para 12, http://www.unhchr.ch/Huridocda/Huridoca.nsf/%28Symbol%29/A.RES.52.132.En?Op endocument. The UNCHR, in Conclusion No. 25 (XXXIII) of 1982 para.(b), has also “recognized that the principle is progressively acquiring the character of a peremptory rule of international law”. Cfr. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Rescue at Sea, Stowaways and Maritime Interception: Selected Reference Materials”, 2nd Edition, December 2011, http://www.re fworld.org/docid/4ee087492.html.

Mariño Menéndez, Fernando, “La Singularidad del Asilo Territorial en el Ordenamiento Internacional y su Desarrollo Regional en el Derecho Europeo”, in Mariño Menéndez, Fernando (ed.), El derecho internacional en los albores del siglo XXI. Homenaje al profesor Juan Manuel Castro-Rial Canosa, Madrid, Trotta, 2002, p. 463 (Translation from Spanish).

Lauterpach and Bethlehem find that the Non-Refoulement obligation is extended also to extradition based in Article 3(2) of the 1957 European Convention on Extradition and Article 4(5) of the 1981 Inter- American Convention on Extradition which preclude extradition when the prosecution of a person amounts in persecution on account of race, religion, nationality or political opinion. Lauterpach and Bethlehem, op. cit., p. 93.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees, 1997, op. cit.

According to the Commentary on the Refugee Convention made by the UNHCR in 1997, Article 33 applies to any Convention refugee who is physically present in the territory of a Contracting State, irrespective of whether his presence in that territory is lawful or unlawful, and regardless of whether he is entitled to benefit from the provision of Article 31 or not. UNHCR, 1997, op. cit.

According to Goodwin-Gill, the application of the principle of non-Refoulement faces several problems among we can count “... the question of “risk”; the personal scope of the principle, including its application to certain categories of asylum seekers, such as stowaways or those arriving directly by boat; exceptions to the principle; extraterritorial application; extradition; and the “contingent” application of the principle in situations of mass influx”. Goodwin-Gill, op. cit., p. 201

Nevertheless, nations tend to establish policies to keep refugees outside their jurisdiction, and, consequently, imperil the protection set up by the 1951 Convention. See Stoyanova, Vladislava, “The Principle of Non-Refoulement and the Right of Asylum Seekers to Enter State Territory” Interdisciplinary Journal of Human Rights Law, vol 3:I, 2008-2009 (“Potential countries of asylum are often unwilling to offer protection. In fact, they actually try to prevent asylum seekers from reaching their territory as well as return those who have managed to enter”). See Newmark, Robert L., “Non- Refoulement Run Afoul: The Questionable Legality of Extraterritorial Repatriation Programs”, Washington University Law Review, vol. 71 (3), 1993 (“Nations have avoided a precise definition of the Non-refoulement obligation to circumvent the strict protective requirement of article 33”).

See Insignares, Silvana and Llain, Shirley, “Migración internacional y conflicto: Un análisis desde la política norteamericana y colombiana”, Revista de Derecho, Universidad del Norte, Edición Especial: 214-244, 2012, p. 226.

Goodwin-Gill, op. cit.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Refugee Protection: A Guide to International Refugee Law”, 1 December 2001, http://www.refworld.org/docid/3cd6a8444.html.

See Worster, William Thomas, “The Evolving Definition of the Refugee in Contemporary International Law”, Berkeley Journal of International Law (BJIL), vol. 30, No. 1, 2012 (explaining that countries, such as, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Mexico, Brazil, and Ecuador have adopted into municipal law the expansive definition of refugee brought by the OAU Convention on the Specific aspects of Refugee Problems, the “Bangkok Principles” and the Cartagena Declaration.)

In Fernandez Arribas, op. cit., p. 10 (translation from Spanish).

See Cohen, Roberta. Legal Grounds for Protection of North Korean Refugees. http://www.brookings.edu/research/opinions/2010/09/north-korea-human-rights-cohen.

See UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Guidelines on International Protection No. 2: “Membership of a Particular Social Group” Within the Context of Article 1A(2) of the 1951 Convention and/or its 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, 7 May 2002, HCR/GIP/02/02, http://www.refworld.org/docid/3d36f23f4.html.

UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), “Fact Sheet No. 20, Human Rights and Refugees”, July 1993, No. 20, available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/4794773f0.html.

Department Of Immigration & Multicultural & Indigenous Affairs Of Australia (DIMIA). “The Principle of Non-Refoulement (Article 33) An Australian Perspective”. http://www.immi.gov.au/media/publications/refugee/convention2002/06_refoulement.pdf.

Fernandez, op. cit., p. 20.

Lauterpacht and Bethlehem, op. cit., p. 113.