The study investigates the different relationships between certain technological and environmental factors and activity-based costing (ABC) diffusion stages. Data were collected through a survey questionnaire sent to Chief Financial Officer of Iranian manufacturing companies. Based on binary logistic regression models, the results show that the relationships between the antecedent factors and ABC diffusion change depending on the diffusion stages. The overall findings suggest that factors that are significantly related to one of ABC diffusion stages (e.g., ABC adoption stage) may not relate to other ABC diffusion stages (e.g., ABC infusion stage). For instance, product diversity and analyzer strategy produce different level of effects on different ABC diffusion stages. The results also reveal that uncertainty-financial and uncertainty-industrial influence two of the ABC diffusion stages, while uncertainty-economical, overheads, and competition influence only one of the ABC diffusion stages.

The main different between ABC and traditional cost accounting system lies in the way manufacturing overhead costs are assigned to products. Under the traditional costing system, the allocation of manufacturing overhead to products is done on the basis of a volume metric such as direct labor hours or production machine hours. However, the direct labor or machine hours are unlikely to be the suitable allocation bases as manufacturing technologies become more sophisticated. Krumwiede (1998) defined ABC as a costing technique that allocates overhead costs to individual activities based on more than one cost allocation base. ABC provides more detailed tracking with different assignment of overhead costs, creates more costs pools, and gives more accurate product costs. ABC is good in managing costs by providing more accurate product cost information (e.g., Ahmadzadeh, Etemadi, & Pifeh, 2011; Englund & Gerdin, 2008; Gilbert, 2007; Kiani & Sangeladji, 2003; Maelah & Ibrahim, 2006; Ríos-Manríquez, Muñoz Colomina, & Rodríguez-Vilariño Pastor, 2014). However, despite its potential use and benefits, the level of adoption of ABC is still low compared to the traditional costing system, such as standard costing system. In fact, Innes and Mitchell (1995) found in their survey that even though ABC is now used by a significant number of large companies, its impact is often restricted in scope and it has also been rejected by a sizeable number of companies. It seems there is a gap exists between the companies that wish to use ABC and the number of companies that have actually adopted and diffused it. ABC literature has shown that understanding the factors that contribute to the success of ABC diffusion is a central concern in the field of management accounting innovation for more than two decades.

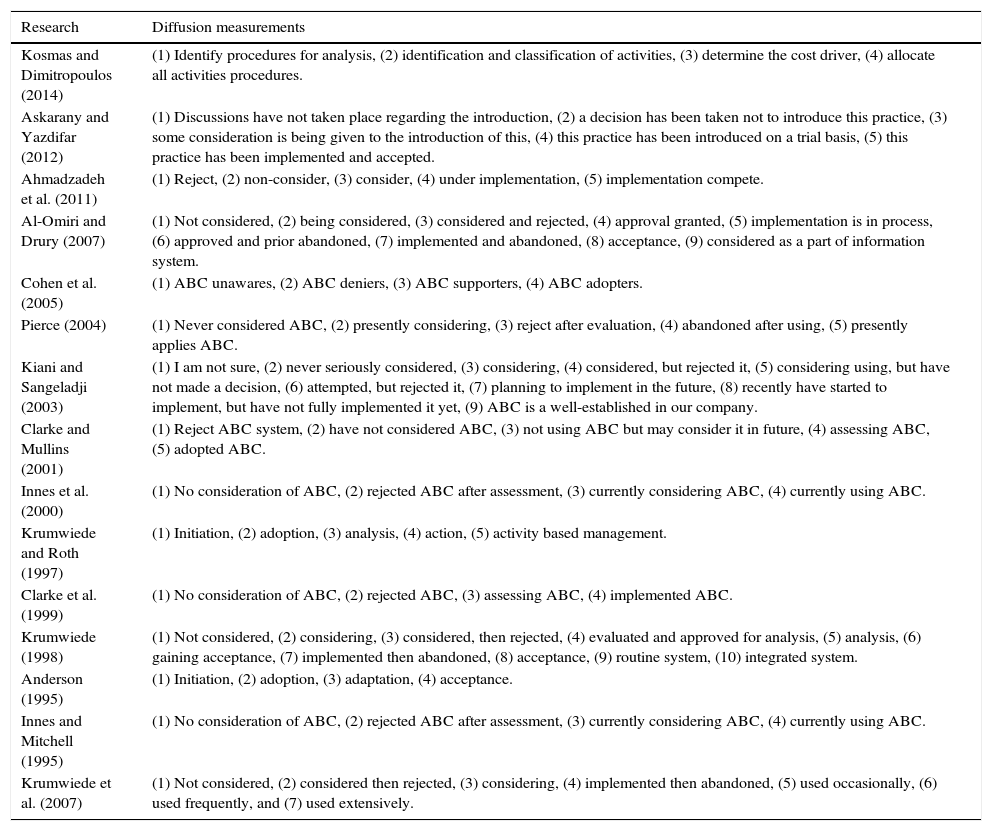

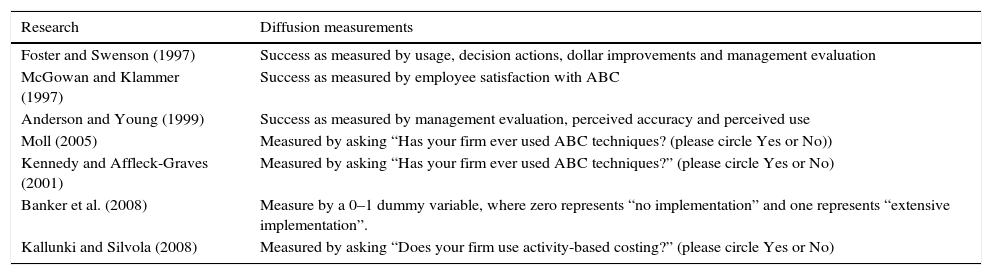

In measuring diffusion of ABC, we can classify ABC researchers into two main groups which apply two types of instruments. The first group explores diffusion of ABC as a process and measures ABC diffusion as multiple diffusion stages (e.g., Ahmadzadeh et al., 2011; Al-Omiri & Drury, 2007; Anderson, 1995; Askarany & Yazdifar, 2012; Kosmas & Dimitropoulos, 2014; Pierce, 2004). The second group looks at ABC diffusion as the changes in the management attitude toward overall ABC success and measures ABC diffusion as a single stage (e.g., Banker, Bardhan, & Chen, 2008; Kallunki & Silvola, 2008; McGowan & Klammer, 1997; Shields, 1995). Under this practice, all firms regardless of their actual diffusion stage are gathered and pooled together in a single stage. In most ABC empirical studies, ABC diffusion is measured using multiple diffusion stages. This practice is seen more meaningful as it better shows the stages where the firms are during their ABC diffusion process.

Considering the diffusion of ABC as a stage model does not look at the diffusion of ABC as a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ option, but makes a distinction between a full diffusion and partial diffusion of ABC by dividing the diffusion process of ABC into a few stages. The main argument is the relationships between some antecedent factors and ABC diffusion may vary by diffusion stages or some factors may be significantly associated with several diffusion stages, but the strength of the association may vary. Therefore, prior studies that pool multiple stages together might find results tend to be biased if such variability exists (Krumwiede, 1998). While ABC studies have received great interest among the accounting researchers, ABC studies looking at different diffusion stages are still lacking within the Iranian context. As such, using the multiple diffusion stages, the current study attempts to empirically examine how certain antecedent factors differently influence each of diffusion stages of ABC of Iranian manufacturing firms. The study identifies two categories of antecedent variables, namely technological and environmental factors. Even though a number of prior ABC studies have examined technological and environmental factors, the dimensions of technological and environmental factors in those studies are different from the current study. In addition, there is no single study that looks at how information technology, product diversity, overheads, perceived environmental uncertainty, competition, and business strategy affect diffusion stages differently. These reasons, together with the Iranian context as well as the use of multiple stages of ABC diffusion, provide some theoretical justifications for conducting this study.

The paper is organized as follows. First, literature review on innovation diffusion theory, ABC diffusion, and factors that influence the diffusion process are discussed, followed by the hypothesis development. After the research method is outlined, the results are reported and followed by the discussion and implications of the findings.

2Literature review and hypothesis development2.1Innovation diffusion theoryAccording to Bjørnenak (1997), innovation is a successful introduction of new ideas among the organizations, even if the idea has previously existed in another area or in a different form. Likewise, Rogers (2003, p. 12) defined an innovation as “an idea, practice, or object that is perceived as new by an individual or other unit of adoption”. Newness is a common measure in the definition of innovation. Rogers characterizes innovation as newness in terms of being either new knowledge or a new decision to adopt. Most studies agree that ABC generally fits the definition of an innovation by Rogers (2003). Bjørnenak and Olson (1999) described ABC as the most popular cost accounting innovation so far. However, Eder and Igbaria (2001) described diffusion as the spread of the usage of an innovation in the organizations. Wolfe (1994) considered innovation diffusion as an approach in which a new idea is accepted (or not accepted) in an organization.

The major subject of the diffusion theory is how and why (or why not) some agents diffuse ideas or phenomena (Bjørnenak, 1997; Malmi, 1999). The diffusion and subsequent use of innovations by potential users are the theoretical basis of the diffusion theory. Diffusion theory is a well-accepted theoretical basis for studying the diffusion of information technology (IT) innovations and management accounting systems (MAS) innovations (e.g., Abernethy & Bouwens, 2005; Eder & Igbaria, 2001).

Rogers (2003) traced the current form of diffusion theory back to the earlier concepts introduced by Gabriel Tarde in 1903. However, in the last two decades studies have been based on the new concepts of diffusion theory introduced by Rogers and others (e.g., Bjørnenak, 1997; Malmi, 1997; Wolfe, 1994). Innovation diffusion research initially focused on the diffusion of innovations of individuals. An individual is an employee of an organization and cannot adopt an innovation until her/his organization has previously diffused it, and, thus, diffusion research considers organizations as the unit of analysis. Further, Gosselin (1997) believes that consideration of organizational innovation was first developed by Burns and Stalker (1961). Hence, in the current study, the unit of analysis is the firms.

Furthermore, Kwon and Zmud (1987) argued that the most important aspect of innovation diffusion theory is that it serves as an organizational effort to diffuse innovations in the organization. Diffusion of an innovation in organizations is typically characterized as a process that starts from initial awareness of the innovation by members of the organization and ends with the successful replacement of the traditional method by the innovation (Malmi, 1997).

The development of ABC diffusion research started with a very thorough case study by Anderson (1995) who applied a diffusion stage model from information system (IS) diffusion. She adopted a 4-stage model from Kwon and Zmud's (1987) as a structure for describing the ABC diffusion at General Motors and found evidences for supporting the model. Anderson (1995) established an important fact that the decision processes at each of diffusion stages are different and different antecedent factors influence the result of the decision process at each stage.

2.2ABC diffusionABC diffusion is a process and there will be a time lag between start and end points of the ABC diffusion. It may also be the case that the idea is not completely diffuse at all (Bjørnenak, 1997). Thus, for diffusion researchers, measurement of diffusion, as a variable, is very important and the inaccurate measurement may distort the results. Most diffusion studies apply two types of measurements to determine the innovation diffusion.

The first group is named as a stage research, which measures ABC diffusion as a stage-model and explore the changes in the level of stages. Diffusion, as stage-models, conceptualizes innovation as a series of stages that unfold over time in which later stages cannot be undertaken until earlier stages have been completed. Wolfe (1994) explained that stage models determine the innovation process, involve identifiable stages and their order by highlighting the stage of an occupant. Cooper and Zmud (1990) believe that stage models help better explain the diffusion process. Stage models are considered useful from both research and practical perspectives. Krumwiede (1998) explained that ABC diffusion is a multi-stage process, which starts with an interest to use ABC and ends with the successful replacement of the traditional costing method by the ABC system. Brown, Booth, and Giacobbe (2004) explained that ABC diffusion relates to the process of carrying out ABC adoption decisions and should be considered as stages. Bjørnenak (1997) believes that the stage models are based on an elaborate set of assumptions and that the stages mark the diffusion mechanism.

Stage research identifies the adoption and infusion as two important points representing two snapshots of the diffusion process that require important decisions. ABC adoption puts ABC into operation manner and shows the firm's decisions on the feasibility of ABC, ABC practice team, and the resources investment. The literature considers ABC adoption as a central event in the ABC diffusion process. Infusion is often cited as an important goal of ABC diffusion. ABC infusion is reached when ABC is extensively used, integrated with the primary financial system, and applied to its full potential (e.g., Ahmadzadeh et al., 2011; Cooper & Zmud, 1990; Krumwiede, 1998). Table 1 summarizes various ABC diffusion stage models as adopted by prior ABC studies.

Some ABC diffusion stages models.

| Research | Diffusion measurements |

|---|---|

| Kosmas and Dimitropoulos (2014) | (1) Identify procedures for analysis, (2) identification and classification of activities, (3) determine the cost driver, (4) allocate all activities procedures. |

| Askarany and Yazdifar (2012) | (1) Discussions have not taken place regarding the introduction, (2) a decision has been taken not to introduce this practice, (3) some consideration is being given to the introduction of this, (4) this practice has been introduced on a trial basis, (5) this practice has been implemented and accepted. |

| Ahmadzadeh et al. (2011) | (1) Reject, (2) non-consider, (3) consider, (4) under implementation, (5) implementation compete. |

| Al-Omiri and Drury (2007) | (1) Not considered, (2) being considered, (3) considered and rejected, (4) approval granted, (5) implementation is in process, (6) approved and prior abandoned, (7) implemented and abandoned, (8) acceptance, (9) considered as a part of information system. |

| Cohen et al. (2005) | (1) ABC unawares, (2) ABC deniers, (3) ABC supporters, (4) ABC adopters. |

| Pierce (2004) | (1) Never considered ABC, (2) presently considering, (3) reject after evaluation, (4) abandoned after using, (5) presently applies ABC. |

| Kiani and Sangeladji (2003) | (1) I am not sure, (2) never seriously considered, (3) considering, (4) considered, but rejected it, (5) considering using, but have not made a decision, (6) attempted, but rejected it, (7) planning to implement in the future, (8) recently have started to implement, but have not fully implemented it yet, (9) ABC is a well-established in our company. |

| Clarke and Mullins (2001) | (1) Reject ABC system, (2) have not considered ABC, (3) not using ABC but may consider it in future, (4) assessing ABC, (5) adopted ABC. |

| Innes et al. (2000) | (1) No consideration of ABC, (2) rejected ABC after assessment, (3) currently considering ABC, (4) currently using ABC. |

| Krumwiede and Roth (1997) | (1) Initiation, (2) adoption, (3) analysis, (4) action, (5) activity based management. |

| Clarke et al. (1999) | (1) No consideration of ABC, (2) rejected ABC, (3) assessing ABC, (4) implemented ABC. |

| Krumwiede (1998) | (1) Not considered, (2) considering, (3) considered, then rejected, (4) evaluated and approved for analysis, (5) analysis, (6) gaining acceptance, (7) implemented then abandoned, (8) acceptance, (9) routine system, (10) integrated system. |

| Anderson (1995) | (1) Initiation, (2) adoption, (3) adaptation, (4) acceptance. |

| Innes and Mitchell (1995) | (1) No consideration of ABC, (2) rejected ABC after assessment, (3) currently considering ABC, (4) currently using ABC. |

| Krumwiede et al. (2007) | (1) Not considered, (2) considered then rejected, (3) considering, (4) implemented then abandoned, (5) used occasionally, (6) used frequently, and (7) used extensively. |

The second group, named as a process research, measures ABC diffusion as the changes in the management attitude toward overall ABC success. Process research includes two main approaches. First approach uses management evaluations of overall changes (Banker et al., 2008; Kallunki & Silvola, 2008; Moll, 2005). This approach usually relies on just one question which is related to overall changes. For example, Kallunki and Silvola (2008) measure ABC diffusion directly from the respondents by asking one question: “Does your firm use activity-based costing?” (please circle Yes or No).

The second approach of process researches measures ABC diffusion by looking at the attributes of success which can be measured by either single or multiple attributes (see Anderson & Young, 1999; Foster & Swenson, 1997; McGowan & Klammer, 1997). For example, McGowan and Klammer (1997) determined success by asking a question relating to managers’ satisfaction with activity management. Further, Foster and Swenson (1997), in their study of the determinants of ABC success, used a multiple attributes which include: usage, decision, actions, dollar improvements, and management evaluation. The main limitation of process research is that it does not distinguish between different levels of ABC usage and does not show the start and end point of diffusion process clearly. As a result, it examines only certain stages or a combination of several stages of ABC diffusion into one single stage. Examining certain factors in one single stage may distort the results as the relationships between the factors and ABC diffusion could vary by diffusion stages. Table 2 summarizes various ABC process models as used by some ABC studies.

Some ABC diffusion process models.

| Research | Diffusion measurements |

|---|---|

| Foster and Swenson (1997) | Success as measured by usage, decision actions, dollar improvements and management evaluation |

| McGowan and Klammer (1997) | Success as measured by employee satisfaction with ABC |

| Anderson and Young (1999) | Success as measured by management evaluation, perceived accuracy and perceived use |

| Moll (2005) | Measured by asking “Has your firm ever used ABC techniques? (please circle Yes or No)) |

| Kennedy and Affleck-Graves (2001) | Measured by asking “Has your firm ever used ABC techniques?” (please circle Yes or No) |

| Banker et al. (2008) | Measure by a 0–1 dummy variable, where zero represents “no implementation” and one represents “extensive implementation”. |

| Kallunki and Silvola (2008) | Measured by asking “Does your firm use activity-based costing?” (please circle Yes or No) |

Diffusion studies have identified a large number of possible factors that are likely to influence innovation diffusion. Kwon and Zmud (1987) categorized these factors into five categories: individual (e.g., job tenure and education); organizational (e.g., size and top management support); technological (e.g., product diversity and dominance of overheads); task (e.g., autonomy and training), and environmental (e.g., uncertainty and competition) factors.

There is a common belief among the innovation diffusion researchers that the impact of certain factors on the innovation diffusion is varying by diffusion stages. Wolfe (1994) argued that the direction of the relationships between antecedent factors and innovation diffusion is related to the stage being considered. In a similar vein, Cooper and Zmud (1990) investigated the diffusion of material requirements planning systems and provided empirical evidence that certain factors influence diffusion stages differently. In the ABC context, Anderson (1995) was the first researcher who found evidences that certain factors differ in their impacts on the various ABC diffusion stages. Following Anderson's (1995) study, several other ABC researchers have found the same evidence (e.g., Brown et al., 2004; Gosselin, 1997; Krumwiede, 1998).

Drawing from this argument, using the Iranian context, the present study attempts to investigate how three technological factors (level of information technology quality, degree of overheads, and diversity), and three environmental factors (environmental uncertainty, competition, and business strategy) influence each stage of the ABC diffusion processes.

2.3.1ABC diffusion and technological factorsChanges in technology, including the growth of automation in the industry, have increased the rate of technological changes. Due to increased support of installing equipment, the influences of technological factors on the innovation diffusion like ABC are increased. Therefore, technological factors are the most important set of factors that have been investigated in ABC diffusion research to date (Al-Omiri & Drury, 2007; Maelah & Ibrahim, 2006). Brown et al. (2004) believe that technological factors are those that relate to the problems that the ABC diffusion is supposed to resolve. The three technological factors that have been identified from the ABC literature are: level of information technology quality, degree of overheads, and diversity.

Information technology (IT) is considered as the ability of existing information systems to influence ABC diffusion (Krumwiede, 1998). Several ABC researchers found evidences that indicate the important role of IT in ABC diffusion. Cooper (1988) described that ABC requires higher levels of IT for providing detailed historical data than the traditional costing method. Cagwin and Bouwman (2002) argued that high IT quality resolves the difficulty in identifying an accurate cost driver within the ABC diffusion stages. In this line, Ebrahimi (1998) found that the quality of IT is likely to influence ABC diffusion among Iranian organizations. Krumwiede (1998) further investigated relationships between IT and ABC adoption or infusion. He found that the quality of IT is positively related to ABC infusion but not to ABC adoption.

Overheads refer to the collection of expenses relating to scheduling, programming, special tooling, engineering, etc. Maelah and Ibrahim (2007) mentioned that due to the increased level of automation, the overhead costs have risen in relative size and importance while direct labor has shrunk accordingly. Krumwiede (1998) argued that in the traditional cost accounting systems the potential for cost distortions which are related to high level of overheads appears to be an important factor that motivate firms to diffuse ABC. Further, Brent (1992) found that the increasing proportion of overhead is one of the important reasons for companies’ initial interest in the ABC system. Some researchers found that degree of overheads is significantly related to ABC infusion (Al-Omiri & Drury, 2007; Krumwiede, 1998). However, Khalid (2005) and Cohen, Venieris, and Kaimenaki (2005) did not find evidence for a relationship between the level of overhead and ABC diffusion. On the whole, enough evidences indicate the different influences of overhead on different ABC diffusion stages.

Product diversity is defined as the variety of products that are manufactured by a firm (Khalid, 2005). It seems that the pace of technological change is rapidly affecting the dimensions of diversity. Cooper (1988) explains that growing product diversity represents another problem associated with traditional cost accounting systems (TCA). Diverse products may include simple or complex products. When products are simple, they may have more direct labor content and limited overheads. In contrast, a complex product may require more overheads. In such cases, using TCA causes cost distortion (Brown et al., 2004; Clarke, Hill, & Stevens, 1999). As a result, firms with diverse production may be motivated to change the traditional cost accounting systems to ABC. Brown et al. (2004), in their mailed survey on Australian firms, found that diversity has a significant and positive association with the interest in ABC, but they did not find a significant association between product diversity and ABC adoption. In another similar study, based on a sample of Ireland firms, Cagwin and Bouwman (2002) found a positive relationship between the level of product diversity and ABC infusion. These evidences show that the relationships between diversity and different ABC diffusion stages change.

2.3.2ABC diffusion and environmental factorsKrumwiede (1998) defined environmental factors as phenomena external to the organization that may influence its management accounting systems. Duncan (1972) described the external environment as relevant physical and social factors outside the organization that are taken directly into consideration. The three environmental factors that have been identified in the current study are: level of competition, business strategy, and perceived environmental uncertainty.

The level of competition refers to the degree of competition that a firm faces in a particular market (Khalid, 2005). Cooper (1988) argued that as the level of competition increases, more reliable cost information is needed. Thus, the competition level has long been recognized as an important factor influencing ABC diffusion (e.g., Al-Omiri & Drury, 2007; Bjørnenak, 1997). Johnson and Kaplan (1987) believe that traditional cost accounting systems are obsolete in the new environment described by intensive competition. Anderson (1995) examined competition in both ABC adoption and infusion and found that competition has a positive influence on ABC adoption but not on ABC infusion. She believes that competition is equally important in motivating ABC adoption. In a study related to MAS infusion, Mia and Clarkef (1999) discovered that the level of competition has a positive influence on infusion of MAS. Likewise, Liu and Pan (2007) also found that competition is an important success factor in ABC diffusion in manufacturing companies in China. With these evidences, it can be concluded that the competition has different relations with different ABC diffusion stages.

Changes in external environment including society have always influenced the strategy because strategy is often shaped by the changes in market, customer needs, and competition (Galbreath, 2009). Therefore, it is reasonable to view strategy as part of the environmental factors. Many researchers believe that that the firms will consider the use of accounting techniques depending on which strategy they follow (e.g., Jusoh, Ibrahim, & Zainuddin, 2006). The current study applied the Miles and Snow (1978) typology strategy that identified four strategic types of organizations according to the rate at which they change their products and markets: prospectors; defenders; analyzers; reactors (Snow & Hrebiniak, 1980). The need to innovate is created by the strategic method chosen by the organization, as each type of business strategy has its own characteristics. Several studies have already shown that there is a link between ABC diffusion and the chosen business strategy (Frey & Gordon, 1999; Gosselin, 1997). Al-Omiri and Drury (2007) found that strategy influences ABC infusion where ABC infusion is higher for defenders than for prospector firms. Meanwhile, Collins, Holzmann, and Mendoza (1997) conducted a survey to determine the influence of Miles and Snow's typology on budgetary adoption (a form of management accounting system). They found that the only significant relationship is between prospector and budgetary adoption. Furthermore, Gosselin (1997) separated ABC diffusion into two main stages, adoption and implementation. He found evidence that ABC adoption is associated with a “prospector” strategy but that implementation is not associated with a specific strategy. In this respect, some issues still need to be addressed in Iranian context such as how a deployment of a particular strategy influences ABC diffusion process because so far none of Iranian studies has mentioned any particular types of innovation belonging to a specific business strategy.

Perceived environmental uncertainty (PEU) is the attribute of the environment that causes uncertainty in decision making (Duncan, 1972; Jusoh, 2008). Bstieler (2005) argued that in a highly uncertain environment, manager's lack of confidence will be more likely generated. This will likely be viewed as situations in which erroneous decisions could be harmful delaying appropriate decision making. The literature has found the importance of PEU in the design of accounting innovation systems (e.g., Ax, Greve, & Nilsson, 2008; Fisher, 1996; Gul, 1991; Jusoh, 2008; Lat & Hassel, 1998). Although there are limited studies specifically examining the relationship between environmental uncertainty and ABC adoption, evidence from other innovation studies can lend some support to such relationship. Anderson (1995) in her case study used a 4 stage model for measuring ABC diffusion and found PEU had a negative influence on the two first diffusion stages of ABC. Chenhall and Morris (1986) found a positive relationship between uncertainty and MAS adoption. Dekker and Smidt (2003) found that the adoption of target costing among Dutch listed manufacturing companies is positively related to the level of uncertainty. In contrast, Kwon and Zmud (1987) argued that environmental uncertainty may have a negative influence on IT infusion because uncertainty may cause firms to ration resources in a manner that constrains innovation. Similarly, Charles and Susanne (1995) found environmental uncertainty negatively related to relationships infusion of strategic/operational planning in small firms.

In summary, the literature has shown that there are two obvious gaps that the current study attempts to fill with respect to ABC studies. One is about the use of multiple stage model and another one is about the choice of technological and environmental factors. It can be concluded that prior studies using multiple stage model of ABC diffusion are still lacking and inconclusive. In addition, how the six factors (information technology, overheads, product diversity, competition, perceived environmental uncertainty, and business strategy) affect multiple stages of ABC diffusion is still not clear. Based on the preceding discussion on the ABC diffusion and its antecedent factors, the following hypothesis was developed:Hypothesis The relationships between antecedent factors (IT quality, product diversity, overhead expenses, competition, perceived environmental uncertainty, and strategy) and ABC diffusion vary by diffusion stages.

Data were collected from a mailed questionnaire survey. The respondents were mainly Chief Financial Officers (CFO) of public listed manufacturing companies of Tehran Stock Exchange (TSE). Manufacturing companies were chosen for this study because ABC is commonly related to costing of a product and it was originally developed for manufacturing companies with significant amount of manufacturing overhead. The emergence of advanced manufacturing technologies has also driven manufacturing companies to use ABC. A total of 400 manufacturing companies were selected from the TSE list year 2008. Out of a total of 400 questionnaires sent out, 300 questionnaires were returned. However, only 188 questionnaires were usable for data analysis, yielding a response rate of 47%.

To suit with the Iranian language, the questionnaire which had been first constructed in English was later translated into Persian language. To ensure that the translation of the instrument to local language is equivalent to the original language, the double translation method was applied. The first translator translated the questionnaire from English into the Persian language. Then, the second translator translated the questionnaire back into the English language. Any inconsistencies, mistranslations, meaning differences, or lost words or phrases were rectified.

3.2Variables measurementABC diffusion: The study used the seven diffusion stage model of Krumwiede, Suessmair, and MacDonald (2007) which include: (1) not considered: ABC has not been seriously considered, (2) considered then rejected: ABC has been considered but later rejected as a costing method, (3) considering: ABC implementation is possible in the future but has not been approved, (4) implemented then abandoned: ABC was previously implemented but is not currently being used, (5) used occasionally: ABC is occasionally used by accountants for internal accounting purposes and by non-accounting management or departments for decision making, (6) used frequently: ABC is frequently used for management decision making; considered normal part of information system, and (7) used extensively: ABC used extensively for management decision making; clear benefits of ABC can be identified. A seven-stage model by Krumwiede et al. (2007) was used in this model as it was refined based on the model developed by Kwon and Zmud (1987) and Cooper and Zmud (1990). Kwon and Zmud (1987) first introduced the innovation process with a six-stage model. Cooper and Zmud (1990) applied this six-stage model to study the diffusion of material requirements planning (MRP) methods. Later, Krumwiede et al. (2007) further converted Cooper and Zmud's (1990) model into a seven-stage model. This seven-stage model seems suitable to be used in this study as it captures more specific diffusion stages of ABC systems compared to other models (see Table 1, diffusion stage models).

Information technology (IT): The question relating to IT was adopted from Krumwiede (1998). The instrument consists of five IT dimensions that include: (1) highly integrated with each other, (2) user friendly, (3) availability of detailed information, (4) availability of cost and performance data, and (5) providing updated real time information. To measure the extent of agreement with each of the statements, a five-point Likert scale was used and the average mean of five items was calculated for the IT variable.

Diversity: Diversity was measured by an instrument developed by Khalid (2005) which classifies firms into five continuous groups based on the number of products produced: 1=less than five products, 2=five to ten, 3=11–20, 4=21–50, and 5=more than 50 products.

Overheads: Instrument for measuring overheads was adopted from Krumwiede (1998). Firms are classified into five continuous groups based on the percentage of overhead expenses included in the cost of products: 1=less than 14%, 2=14–19%, 3=20–24%, 4=25–29%, and 5=more than 29%.

Perceived environmental uncertainty (PEU): Questions relating to environmental uncertainty were adopted from Jusoh (2008). Her instrument includes 28 items in seven dimensions which include: suppliers, competitors, customers, financial/capital markets, government regulations, labor unions, and economics/politics/technology. All of the items were measured on a five-point Likert-type scale (varying from “highly predictable” to “highly unpredictable”). The mean score of all the items was used to represent the overall PEU score in the data analysis.

Competition: Competition was assessed based on instrument from Cohen et al. (2005). Firms are classified into five continuous groups based on the number of competitors in a particular market: (1)=no competitors, (2)=one to three, (3)=four to ten, (4)=11–20 and (5)=more than 20 competitors.

Business strategy: The questions regarding business strategy were adopted from Jusoh and Parnell (2008). This instrument includes forty-eight items in twelve questions. Each question consists of four statements which are related to each possible strategy type proposed by Miles and Snow (1978). Respondents were asked to indicate agreement or disagreement with each statement concerning their organization by using a five-point Likert scale. Strategy is operated by taking the mean score across the twelve items in four strategic types. Then, for each firm the degree of the mean value which is classified into four strategic types is compared. The highest value indicates that the firm emphasizes a given strategy.

4Results4.1Validity and factor analysisThe present study applied three important forms of validity – face, content and factorial validity (Sekaran, Cavana, & Delahaye, 2000). For testing face validity and clarity of meaning, a survey to 30 individual financial managers is conducted. Content validity is established through a review of the instrument by ten experts including experienced accountants and academics. Based on the results of these tests a few of the questions were modified. For testing factorial validity, a factor analysis is conducted for all the multi-item measurement except for business strategy. The measurement of strategy is specially designated for each strategic type based on Miles and Snow's typology. The current study considers each type as a whole and it does not attempt to look at the dimensions of each type of business strategy; thus, factor analysis was not employed for the strategy type's items.

Zikmund (2002) believes that the general objective of factor analysis is to summarize information contained in a large number of dimensions into a smaller number of factors. The principal component analysis method and varimax rotation matrix value were used for determining the groups of items. The cut-off point of 0.50 or greater for factor loading was used for identifying significant factor loadings as suggested by Hair, Anderson, Tatham, and Black (1998).

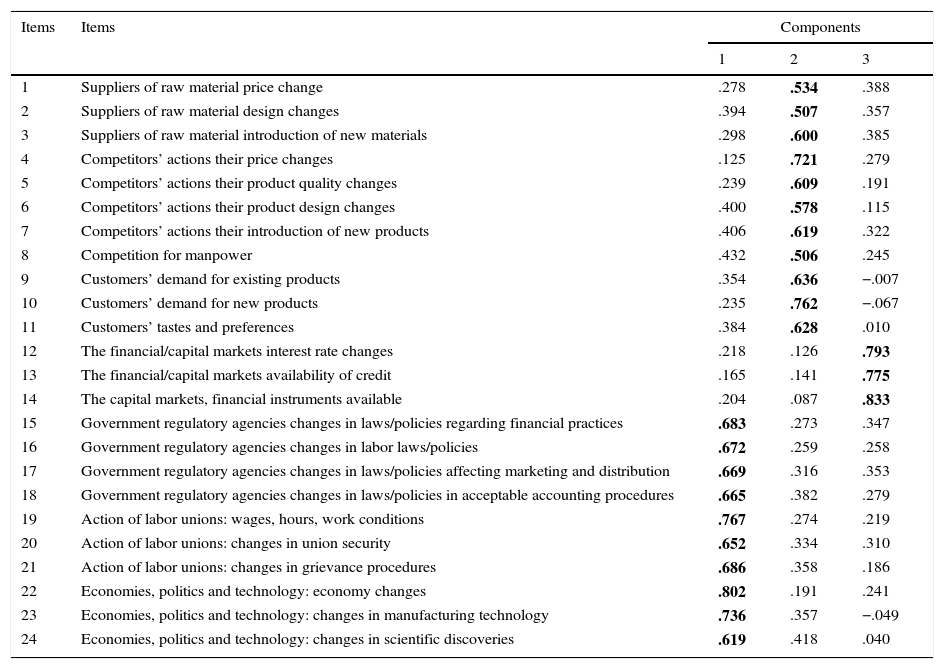

For IT, only one factor was extracted with cumulative percentage of variance of 85%. For PEU, three component factors were extracted with eigenvalues exceeding 1.00 and covering a total of 61.32% of variance (see Table 3). As shown in Table 3, the cut-off point of .50 or greater for factor loading for each item was used (values in bold). This is in consistent with Hair et al. (1998). Factor 1 includes 10 items with 25.89% of variance. These 10 items were combined and named “perceived environmental uncertainty-economical”. Factor 2 was named “perceived environmental uncertainty-industrial as it has 11 items pertaining to the industry and it accounts for 21.79% of the variance. Factor 3 includes 3 items related to finance, which accounts for 13.65% of variance and was named “perceived uncertainty-financial”. Table 3 shows the rotated component matrix rotated, which indicates the factor loadings for each item of PEU.

Rotated component matrix-PEU 24 items of 28 items.

| Items | Items | Components | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 1 | Suppliers of raw material price change | .278 | .534 | .388 |

| 2 | Suppliers of raw material design changes | .394 | .507 | .357 |

| 3 | Suppliers of raw material introduction of new materials | .298 | .600 | .385 |

| 4 | Competitors’ actions their price changes | .125 | .721 | .279 |

| 5 | Competitors’ actions their product quality changes | .239 | .609 | .191 |

| 6 | Competitors’ actions their product design changes | .400 | .578 | .115 |

| 7 | Competitors’ actions their introduction of new products | .406 | .619 | .322 |

| 8 | Competition for manpower | .432 | .506 | .245 |

| 9 | Customers’ demand for existing products | .354 | .636 | −.007 |

| 10 | Customers’ demand for new products | .235 | .762 | −.067 |

| 11 | Customers’ tastes and preferences | .384 | .628 | .010 |

| 12 | The financial/capital markets interest rate changes | .218 | .126 | .793 |

| 13 | The financial/capital markets availability of credit | .165 | .141 | .775 |

| 14 | The capital markets, financial instruments available | .204 | .087 | .833 |

| 15 | Government regulatory agencies changes in laws/policies regarding financial practices | .683 | .273 | .347 |

| 16 | Government regulatory agencies changes in labor laws/policies | .672 | .259 | .258 |

| 17 | Government regulatory agencies changes in laws/policies affecting marketing and distribution | .669 | .316 | .353 |

| 18 | Government regulatory agencies changes in laws/policies in acceptable accounting procedures | .665 | .382 | .279 |

| 19 | Action of labor unions: wages, hours, work conditions | .767 | .274 | .219 |

| 20 | Action of labor unions: changes in union security | .652 | .334 | .310 |

| 21 | Action of labor unions: changes in grievance procedures | .686 | .358 | .186 |

| 22 | Economies, politics and technology: economy changes | .802 | .191 | .241 |

| 23 | Economies, politics and technology: changes in manufacturing technology | .736 | .357 | −.049 |

| 24 | Economies, politics and technology: changes in scientific discoveries | .619 | .418 | .040 |

| Rotation sums of squared loadings | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Components | Total | % of variance | Cumulative % of variance |

| 1 | 6.212 | 25.885 | 25.885 |

| 2 | 5.230 | 21.790 | 47.674 |

| 3 | 3.275 | 13.647 | 61.321 |

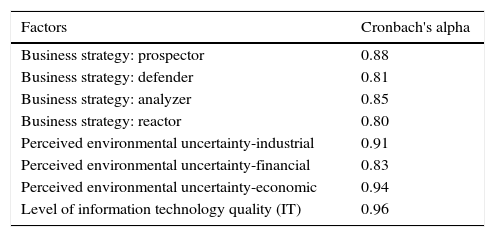

Reliability of the multi-item measurement scale in the questionnaire was estimated by using Cronbach's alpha, the degree of internal consistency among the multipoint-scaled items in the questionnaire (Sekaran et al., 2000). The coefficient alpha varies from 0 to 1 and the value of 0.60 or above indicates satisfactory internal consistency (Malhotra, Hall, Shaw, & Oppenheim, 2004). Table 4 presents Cronbach's alpha coefficients of each of the dimensions and shows that the overall reliability of all dimensions exceeds the conventional level of acceptability (0.60 or above).

Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the multi-items.

| Factors | Cronbach's alpha |

|---|---|

| Business strategy: prospector | 0.88 |

| Business strategy: defender | 0.81 |

| Business strategy: analyzer | 0.85 |

| Business strategy: reactor | 0.80 |

| Perceived environmental uncertainty-industrial | 0.91 |

| Perceived environmental uncertainty-financial | 0.83 |

| Perceived environmental uncertainty-economic | 0.94 |

| Level of information technology quality (IT) | 0.96 |

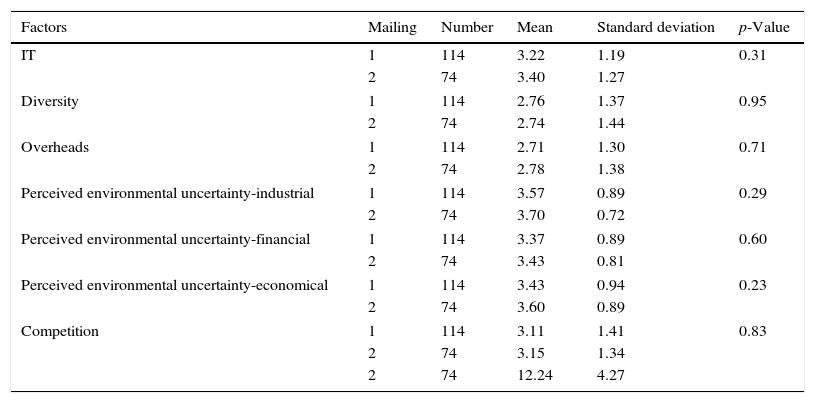

Previous researchers (e.g. Fullerton & McWatters, 2002; Guerreiro, Rodrigues, & Craig, 2012) asserted that the non-response bias is a potential problem when a mail survey is employed to collect data. To test for possible existence of non-response bias, the validity of the first and second mailing was examined using the t-test that compares the mean-values of each variable in the study. As shown in Table 5, the t-test results for non-response bias indicate that there are no significant differences between the early respondents and late respondents for all variables.

t-Test for non-response bias.

| Factors | Mailing | Number | Mean | Standard deviation | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IT | 1 | 114 | 3.22 | 1.19 | 0.31 |

| 2 | 74 | 3.40 | 1.27 | ||

| Diversity | 1 | 114 | 2.76 | 1.37 | 0.95 |

| 2 | 74 | 2.74 | 1.44 | ||

| Overheads | 1 | 114 | 2.71 | 1.30 | 0.71 |

| 2 | 74 | 2.78 | 1.38 | ||

| Perceived environmental uncertainty-industrial | 1 | 114 | 3.57 | 0.89 | 0.29 |

| 2 | 74 | 3.70 | 0.72 | ||

| Perceived environmental uncertainty-financial | 1 | 114 | 3.37 | 0.89 | 0.60 |

| 2 | 74 | 3.43 | 0.81 | ||

| Perceived environmental uncertainty-economical | 1 | 114 | 3.43 | 0.94 | 0.23 |

| 2 | 74 | 3.60 | 0.89 | ||

| Competition | 1 | 114 | 3.11 | 1.41 | 0.83 |

| 2 | 74 | 3.15 | 1.34 | ||

| 2 | 74 | 12.24 | 4.27 | ||

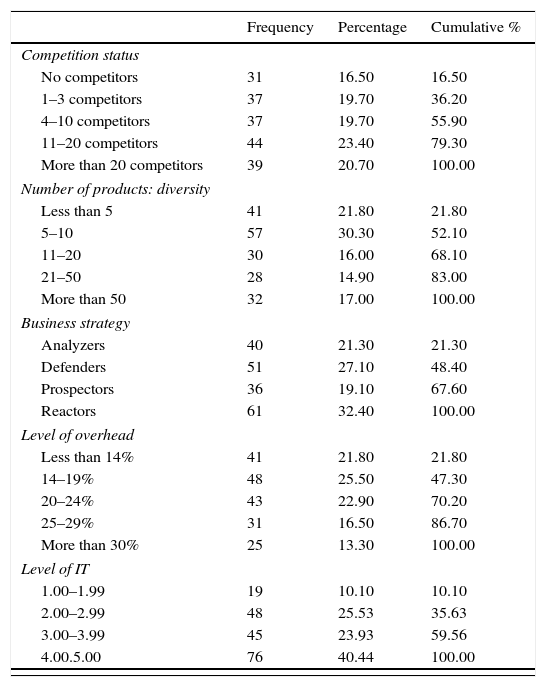

Table 6 presents the descriptive statistics for all the variables. For ABC diffusion stages, Table 6 shows that there is no responding firm in any of these three stages: Stage 2, Stage 4, and Stage 6. No responding firm in Stage 2 and Stage 4 may due to the unwillingness of the respondents to admit that they do not have enough knowledge about ABC system. They may have evaluated or tried to implement ABC, but later rejected or abandoned it. There are only 33 firms considered as ABC adopters (Stage 5=20 firms, Stage 7=13 firms). Due to this relatively small sample size for adopters, the study also failed to capture any respondents in Stage 6. There are 155 firms considered as non-adopters which were captured in Stage 1 (112 firms) and Stage 3 (43 firms). Low rate of ABC adoption is rather common in developing countries such as Iran. This is consistent with some survey evidence which suggest that the overall rates of implementation have been low despite a growing awareness of ABC (Cohen et al., 2005; Innes, Mitchell, & Sinclair, 2000; Pierce & Brown, 2004).

Descriptive statistics.

| Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competition status | |||

| No competitors | 31 | 16.50 | 16.50 |

| 1–3 competitors | 37 | 19.70 | 36.20 |

| 4–10 competitors | 37 | 19.70 | 55.90 |

| 11–20 competitors | 44 | 23.40 | 79.30 |

| More than 20 competitors | 39 | 20.70 | 100.00 |

| Number of products: diversity | |||

| Less than 5 | 41 | 21.80 | 21.80 |

| 5–10 | 57 | 30.30 | 52.10 |

| 11–20 | 30 | 16.00 | 68.10 |

| 21–50 | 28 | 14.90 | 83.00 |

| More than 50 | 32 | 17.00 | 100.00 |

| Business strategy | |||

| Analyzers | 40 | 21.30 | 21.30 |

| Defenders | 51 | 27.10 | 48.40 |

| Prospectors | 36 | 19.10 | 67.60 |

| Reactors | 61 | 32.40 | 100.00 |

| Level of overhead | |||

| Less than 14% | 41 | 21.80 | 21.80 |

| 14–19% | 48 | 25.50 | 47.30 |

| 20–24% | 43 | 22.90 | 70.20 |

| 25–29% | 31 | 16.50 | 86.70 |

| More than 30% | 25 | 13.30 | 100.00 |

| Level of IT | |||

| 1.00–1.99 | 19 | 10.10 | 10.10 |

| 2.00–2.99 | 48 | 25.53 | 35.63 |

| 3.00–3.99 | 45 | 23.93 | 59.56 |

| 4.00.5.00 | 76 | 40.44 | 100.00 |

| Min | Max | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental uncertainty-factors | |||

| Perceived environmental uncertainty-economical | 1 | 5 | 3.51 |

| Perceived environmental uncertainty-industrial | 1 | 5 | 3.63 |

| Perceived environmental uncertainty-financial | 1 | 5 | 3.02 |

| Uncertainty-overall | 1 | 5 | 3.51 |

| Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABC diffusion stages | |||

| Stage 1 – not considered | 112 | 59.58 | 59.58 |

| Stage 2 – considered then rejected | 0 | 0.00 | 59.58 |

| Stage 3 – considering to ABC | 43 | 22.87 | 82.45 |

| Stage 4 – implemented then abandoned | 0 | 0.00 | 82.45 |

| Stage 5 – used occasionally | 20 | 10.64 | 93.09 |

| Stage 6 – used frequently | 0 | 0.00 | 93.09 |

| Stage 7 – used extensively | 13 | 6.91 | 100.00 |

As the data only captures responding firms in four stages (Stage 1, Stage 3, Stage 5, and Stage 7), a 4-stage model was then used in the data analysis. A 4-stage model is also acceptable and considered as a continuous and complete diffusion model where other ABC researchers have also proposed it (e.g., Anderson, 1995; Clarke et al., 1999; Gosselin, 1997; Innes et al., 2000). In the 4-stage model, a company is considered as an ABC adopter if it attains at least Stage 3 (or Stage 5 in the original model) and as ABC infuser if it attains Stage 4 (or Stage 7 in the original model).

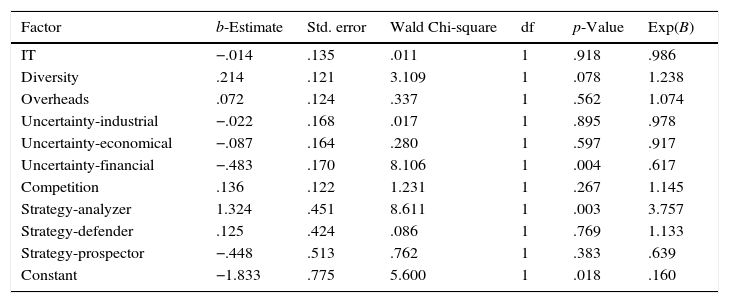

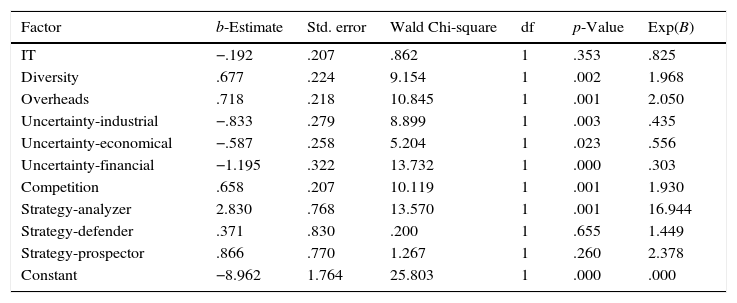

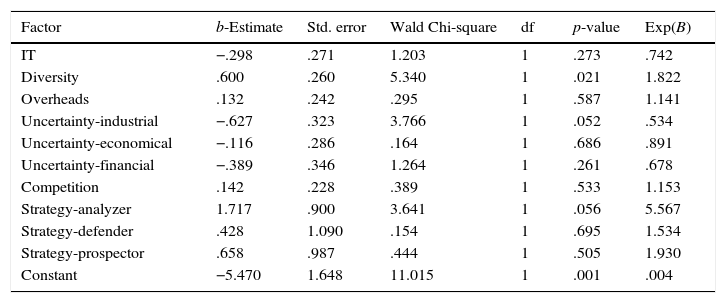

4.4Hypothesis testingThe study hypothesizes that the relationships between antecedent variables vary according to the ABC diffusion stages. To test the hypothesis, three binary logistic regression models were performed as shown in Tables 7–9 to examine how coefficient changes by stage. Panel A tests the influence of antecedent variables as firms move from Stage 1 (not considering ABC) to Stage 3 (considering ABC) through Stage 5 and Stage 7 (adopting ABC). As firms in Stage 5 or Stage 7 must first go through Stage 3, they can be combined together with firms in Stage 3 so long they are in the order of diffusion stage. Panel B tests the influence of antecedent variables as firms move from non-adoption categories (Stage 1 through Stage 3) to adoption categories (Stage 5 through Stage 7). Panel C examines the influence of antecedent variables as firms move from non-adoption or non-infusion categories (Stage 1 through Stage 5) to infusion category (Stage 7). Hence, all the panels represent categories of companies that are in the order of diffusion stage.

Binary logistic result: panel A diffusion stages.

| Factor | b-Estimate | Std. error | Wald Chi-square | df | p-Value | Exp(B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IT | −.014 | .135 | .011 | 1 | .918 | .986 |

| Diversity | .214 | .121 | 3.109 | 1 | .078 | 1.238 |

| Overheads | .072 | .124 | .337 | 1 | .562 | 1.074 |

| Uncertainty-industrial | −.022 | .168 | .017 | 1 | .895 | .978 |

| Uncertainty-economical | −.087 | .164 | .280 | 1 | .597 | .917 |

| Uncertainty-financial | −.483 | .170 | 8.106 | 1 | .004 | .617 |

| Competition | .136 | .122 | 1.231 | 1 | .267 | 1.145 |

| Strategy-analyzer | 1.324 | .451 | 8.611 | 1 | .003 | 3.757 |

| Strategy-defender | .125 | .424 | .086 | 1 | .769 | 1.133 |

| Strategy-prospector | −.448 | .513 | .762 | 1 | .383 | .639 |

| Constant | −1.833 | .775 | 5.600 | 1 | .018 | .160 |

| Test | Wald Chi-square | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Omnibus test of model coefficients | 27.24 | 10 | 0.002 |

| Goodness-of-fit test (Hosmer and Lemeshow) | 9.02 | 8 | 0.341 |

Note: −2 log likelihood=226.44, Cox and Snell R2=0.35, Nagelkerke R2=0.18.

Binary logistic result: panel B diffusion stages.

| Factor | b-Estimate | Std. error | Wald Chi-square | df | p-Value | Exp(B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IT | −.192 | .207 | .862 | 1 | .353 | .825 |

| Diversity | .677 | .224 | 9.154 | 1 | .002 | 1.968 |

| Overheads | .718 | .218 | 10.845 | 1 | .001 | 2.050 |

| Uncertainty-industrial | −.833 | .279 | 8.899 | 1 | .003 | .435 |

| Uncertainty-economical | −.587 | .258 | 5.204 | 1 | .023 | .556 |

| Uncertainty-financial | −1.195 | .322 | 13.732 | 1 | .000 | .303 |

| Competition | .658 | .207 | 10.119 | 1 | .001 | 1.930 |

| Strategy-analyzer | 2.830 | .768 | 13.570 | 1 | .001 | 16.944 |

| Strategy-defender | .371 | .830 | .200 | 1 | .655 | 1.449 |

| Strategy-prospector | .866 | .770 | 1.267 | 1 | .260 | 2.378 |

| Constant | −8.962 | 1.764 | 25.803 | 1 | .000 | .000 |

| Test | Wald Chi-square | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Omnibus test of model coefficients | 72.36 | 10 | 0.001 |

| Goodness-of-fit test (Hosmer and Lemeshow) | 9.96 | 8 | 0.268 |

Note: −2 log likelihood=102.34, Cox and Snell R2=0.32, Nagelkerke R2=0.53.

Binary logistic result: panel C diffusion stages.

| Factor | b-Estimate | Std. error | Wald Chi-square | df | p-value | Exp(B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IT | −.298 | .271 | 1.203 | 1 | .273 | .742 |

| Diversity | .600 | .260 | 5.340 | 1 | .021 | 1.822 |

| Overheads | .132 | .242 | .295 | 1 | .587 | 1.141 |

| Uncertainty-industrial | −.627 | .323 | 3.766 | 1 | .052 | .534 |

| Uncertainty-economical | −.116 | .286 | .164 | 1 | .686 | .891 |

| Uncertainty-financial | −.389 | .346 | 1.264 | 1 | .261 | .678 |

| Competition | .142 | .228 | .389 | 1 | .533 | 1.153 |

| Strategy-analyzer | 1.717 | .900 | 3.641 | 1 | .056 | 5.567 |

| Strategy-defender | .428 | 1.090 | .154 | 1 | .695 | 1.534 |

| Strategy-prospector | .658 | .987 | .444 | 1 | .505 | 1.930 |

| Constant | −5.470 | 1.648 | 11.015 | 1 | .001 | .004 |

| Test | Wald Chi-square | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Omnibus test of model coefficients | 18.60 | 10 | 0.046 |

| Goodness-of-fit test (Hosmer and Lemeshow) | 6.02 | 8 | 0.645 |

Model summary: −2 log likelihood=75.94, Cox and Snell R2=0.094, Nagelkerke R2=0.24.

Panel A in Table 7 shows the association between eight factors (IT, diversity, overheads, uncertainty-industrial, uncertainty-economical, uncertainty-financial, competition, and strategy) and a binary variable. The binary variable has only two values, 0 for firms at Stage 1 and 1 for firms at Stage 3, 5, and 7. As shown in Table 7, under Model Summary, the −2 log likelihood statistics is equal to 226.5 which show a rich value of prediction. The Cox and Snell R2 is equal to 0.135 which is equivalent to R2 in a multiple regression. The Nagelkerke R2 is equal 0.182 which attempts to quantify the proportion of explained variation in the logistic regression model. The omnibus tests of model coefficients indicate that the Chi-square=27.239, df=10, p<0.001. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test was also conducted to ensure the goodness of fit of the model. The finding of this test shows the non-significance p-value (p=0.341). This result indicates that the predicted model is not significantly different from the observed values and the model fits well. The present study reports the results of logistic regression analysis based on Peng et al.’s (2002) suggestion. This format summarizes the results in a table that reports the following information: The b parameter estimated standard error, the degrees of freedom, the Wald statistic, p value level, and the odds ratio Exp(B) for each factor. Exp(B) shown in the final column of Table 7 is an indicator of the change in odds resulting from a unit change in the indicator. Value greater than 1 indicate that as the predictor increases, the odds of the outcome occurring increase; equally, a value less than one indicate that as the predictor increases, the odd of the outcome occurring decrease. This is consistent with the signs of the regression coefficients. As shown, diversity, uncertainty-financial, and strategy-analyzer are significant for panel A. For each significant value the result is explained as follows:

The level of diversity affects the panel A significantly at p<0.10 (p-values=0.078). The b parameter for competition is equal to +0.21. The positive b coefficients indicate that diversity increases the logistic of the panel A. The odds ratio Exp(B) shows that a one-unit increase in the value of diversity increases the probability of panel A from 1 to 1.24. The results suggest that firms that face higher product diversity are more likely to access Stage 3 and higher.

As shown in Table 7, perceived environmental uncertainty-financial is significant at the level of p<0.01 (p-value=0.004, b=−0.48), which means that the influence of uncertainty-financial on panel A is negative and significant. The negative b coefficients indicate that if the uncertainty-financial increases the probability of panel A decreases. The odds ratio Exp(B) shows that a one-unit increase in the value of uncertainty-financial decreases the probability of panel A from 1 to 0.62. The results suggest that firms that face lower uncertainty-financial tend to access Stage 3 and higher.

Further, in the binary logistic model, business strategy types are considered as a dummy variable and 3 (k−1) dummy variables are used for business strategy. In this dummy variable, strategy-reactor is considered as the reference. Table 7 shows that in panel A, only strategy-analyzer is significant at p<0.01 (b=+1.32), which indicates that the strategy-analyzer has a more positive influence on panel A than strategy-reactors. The odds ratio Exp(B) value indicates an expected change in panel A when strategy-analyzer is changed by one unit. The odds ratio Exp(B) for strategy-analyzer is equal to 3.76, which means that the probability of panel A in firms who are using strategy-analyzer is 3.76 times higher than strategy-reactors. These results show that analyzer firms are more motivated to be at Stage 3 and higher.

4.4.2Antecedent factors and non-adoption to adoption categoriesAdoption has traditionally been the central event in innovation studies. The 7-stage model of the study defines adopter firms as firms who attain at least stage 5. Panel B is a binary logistic model which dependent variable has only two values, 0 for firms in Stage 1 or 3 and 1 for firms in Stage 5 or 7. Panel B assess the influence of antecedent factors on ABC adoption as firm move from non-adopting stages to adopting stages. The results in Table 8 reveal that −2 log likelihood statistics=102.314, Cox and Snell R2=0.319, and Nagelkerke R2=0.53. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test shows nonsignificant p-value (p-value=0.268) indicating that the predicted model is not significantly different from observed values and the model fits well. All variables are significant for Panel B except for IT.

Diversity has a positive influence on ABC adoption at p<0.01 level (b=+0.68). The odds ratio Exp(B) is equal to 1.97, indicating that a one-unit increase in the value of diversity increases the probability of adoption from 1 to 1.84. The result suggests that firms with a high diversity of products are more likely to adopt ABC system when they move to Stage 5 and higher. Overheads also show a positive and significant relationship with ABC adoption (p-values=0.001, b=+0.72). This result suggests that firms with high overheads are more likely to adopt the ABC system as they move to Stage 5 and higher. Further, all three dimensions of PEU have negative and significant influences on ABC adoption. The results show that PEU appears to play a major negative role in the adoption of ABC. The results suggest that firms which face lower uncertainty tend to adopt the ABC system when they reach Stage 5 and higher. Moreover, competition is significant at p<0.01 level (b=+0.66). The positive b coefficient indicates that competition increases the probability of the ABC adoption. These results suggest that non-competitive situations such as a monopoly can lead to the use of traditional cost accounting rather than using ABC. In addition, strategy-analyzer also has a positive and significant influence on ABC adoption indicating that the analyzer firms are more motivated to adopt the ABC system when they are in Stage 5 and higher.

4.4.3Antecedent factors and non-adoption or non-infusion categories to infusion categorySome researchers named the infusion of ABC as ABC success, while adoption is a starting point for using ABC. Firms were labeled as infusers if they attain Stage 7. Thus, panel C investigates the influence of antecedent factors on infusion ABC. Panel C is a binary logistic model that dependent variable value is 0 for firms in either Stage 1, 3 or 5 and 1 for firms in Stage 7. The results for panel C were reported in Table 9 showing the −2 log likelihood statistics equals to 75.94, the Cox and Snell R2 equals to 0.094 and the Nagelkerke R2 parameter equals to 0.24. The Hosmer and Lemeshow shows nonsignificant p-value indicating that the predicted model is not significantly different from observed values and model fits well. As shown in Table 9, diversity, uncertainty-industrial, and strategy-analyzer are significant for panel C. The results suggest that firms which face higher diversity and lower uncertainty-industrial tend to be an ABC infuser. Further, the analyzer firms are more motivated to access to Stage 7.

5Discussion and implicationsThis study provides some empirical evidences on the influences of several technological and environmental factors on the ABC diffusion stages. All the panels (A, B, and C) provide the ordered logit coefficients that represent the specific effects of independent variables on the log of the odds ratio for reaching one stage vs. the previous stage. The coefficients show how the effects change by stage.

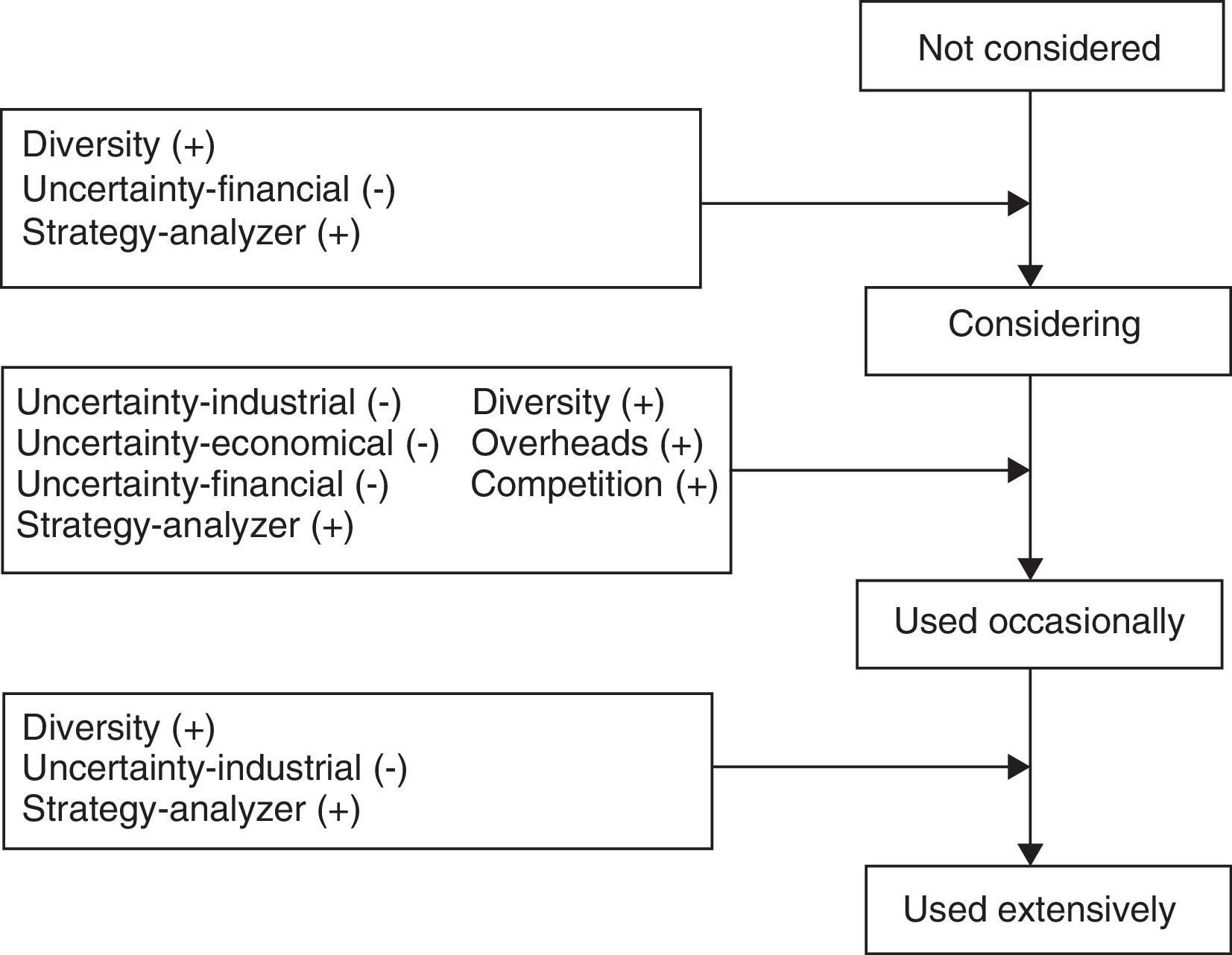

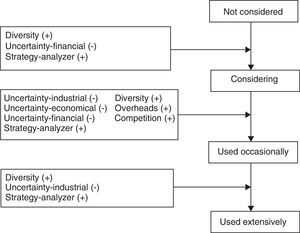

The hypothesis predicts that the influences of antecedent variables will vary according to the ABC diffusion stages. The overall results reasonably explain that the influence of various antecedent variables may vary according to the ABC diffusion stages, thus, the hypothesis is supported. To better understand the overall findings, the antecedent factors which were found significant at each ABC diffusion stage are summarized in Fig. 1. The results show that only diversity, uncertainty-financial and strategy-analyzer are significant for panel A as companies move from Stage 1 (not considered) to Stage 3 (considering). For panel B, as companies progress from Stage 1 and Stage 3 to Stage 5 (used occasionally) and 7 (used extensively), the results reveal that seven antecedent factors have significant influence on the ABC diffusion stages. These factors are diversity, overheads, uncertainty-industrial, uncertainty-economical, uncertainty-financial, competition, and strategy-analyzer. Furthermore, the results also show that diversity, uncertainty-industrial and strategy-analyzer are significant for panel C as companies move to final stage (Stage 7). These results indicate that from seven factors which are significant for all panels, only two factors (product diversity and strategy-analyzer) have positive influences on all the ABC diffusion stages. But the degree of importance of diversity and strategy-analyzer varies by each panel (as shown by the different amounts of b coefficients). This indicates that product diversity (measured by number of products produced) and analyzer strategy have the same influence on all the ABC diffusion stages but with a different strength. As firm increases number of products they produced, the overhead cost allocation becomes more complex. As a result, product diversity becomes an important influencing factor for firms in all stages of ABC diffusion. Product diversity seems most dominant in firms that are in transition point between the non-adoption and adoption stages (panel B). The findings also suggest that the analyzers seem to place great importance on innovation such ABC. This is consistent with a study by Olson and Slater (2002) who found that the high performing analyzers placed greater emphasis on innovation and growth perspectives of balanced scorecard (BSC) performance measures.

The results also reveal that uncertainty-financial (panel A and panel B) and uncertainty-industrial (panel B and panel C) influence two of the ABC diffusion stages, while uncertainty-economical, overheads, and competition (panel B) influence only one of the ABC diffusion stages. Although adoption stage labeled as “used occasionally” (Stage 5) is necessary for infusion to occur (Stage 7), some factors affecting adoption may actually have no effect upon infusion.

Further, as shown in Tables 7–9, each factor affects the progression from panel A to the other two panels differently. Thus, the model is adequate based on the residual regression analysis to support the innovation diffusion theory. Cooper and Zmud (1990) believe that change occurs in stages and the significance influences of factors might vary across the stages. The overall findings of the current study suggest that factors that significantly influence one of the ABC diffusion stages (e.g., ABC adoption) may not influence other ABC diffusion stages (e.g., ABC infusion). The findings are quite consistent with those findings from some prior ABC studies (e.g., Anderson, 1995; Askarany & Yazdifar, 2012; Krumwiede, 1998) even though their studies used a different ABC diffusion stage model and different contextual factors. The findings suggest ABC researchers should define ABC diffusion as stage model instead of combining several stages of ABC diffusion in one stage for the later approach may distort the results.

There are several general implications from the findings. The findings imply that having a good understanding of how the antecedent factors influence the different stages of ABC diffusion is an important knowledge for management or cost accountants to enhance their firms’ ABC implementation. Besides, ABC innovation, the findings also have some implication to studies unrelated to management accounting system innovations in examining whether certain factors affect implementation stages differently. This study also makes some important contributions to ABC and innovation literature, in particular within the Iranian context, by providing additional empirical evidence on the contextual factors that influence the diffusion of ABC. This study employed a different set of contextual and organizational variables which have not been much studied before using the multiple stage of ABC diffusion. The specific findings were noted for the variables ‘product diversity’ and ‘analyzer strategy’ in which they show most significant impact for the transition point between the non-adopting and adopting stages. One plausible explanation for these findings may be because companies that move from the non-adopting to adopting stages of ABC find that they could be more innovative and competitive by adopting analyzer strategy and having more product diversity which can be obtained through the adoption of ABC.

Several limitations of this study must be noted. The present study only covers manufacturing sector companies selected from the Tehran Stock Exchange. Therefore, any generalizations of the results to other sectors (e.g., distribution, retail, services, transportation, and others) should be treated with caution. The relatively small sample size also contributes to another limitation. From 188 companies that responded to the questionnaire, only 33 companies that actually implemented ABC, either occasionally or extensively. Small sample size would lead to difficulty in getting significant results as each stage of ABC diffusion is not well represented and distributed. In this respect, future research should be carried out at a larger scale involving other sectors such as services and non-profit sectors, as well as government organizations in order to get a better understanding of the ABC system and its application. Moreover, the survey approach used in this study contributes several weaknesses. As the data were collected at a single point in time, it is difficult to capture the changes in the association between antecedent factors and the ABC diffusion stages over time. In relation to strategy variable, relying on cross-sectional data does not permit us to say whether such strategic patterns remain stable over time. In addition, in the case of Iran, the use of perceptual data may contribute a limitation in terms of interpretation of the nature of ABC implementation among the respondents where the interpretation may be different from the one used in the US and western countries.