Child abuse is seen as a type of family violence because it is usually exercised by relatives and people close to the children. At the same time a child may experience more than one type of violence and may live in homes exposed to gender-based violence. The aim of this study is to determine the type of abuse suffered by the children seen as victims, by court order, and the co-occurrence of direct and indirect forms of violence, such as exposure to violence between parents and adult members of the family. The relationship of violence with sociodemographic and health variables of the minor, variables of the family, of the parents’ health, and possible victimisation of the mother is analysed.

MethodA descriptive and retrospective study was conducted using data extracted from the forensic clinical records of minors examined in a Forensic Evaluation Unit of Bilbao during the period of 2009–2015. The studied population included 675 minors from 0 to 17 years old, victims of abuse, who were analysed individually at the hands of forensic doctors or psychologists by court order. The study included, among others, physical and psychological violence, sexual violence, being witnesses of violence between adults in the family and multiple victimisation.

ResultsIn the minors analysed, the most prevalent violence was emotional abuse and witnessing violence between adults in the family, followed by physical violence, multiple victimisation and, in the last place of frequency, sexual violence. There is a high co-occurrence between types of abuse. There is a high co-ocurrence among types of violence in minors, and violence towards minors and gender violence are close phenomena. It is children between 5 and 11 years old that most frequently suffer all subtypes of abuse. Most of the complaints come from the family, especially the mother (58%) and the one mainly reported is the father (47%), followed by the mother (N=110). It is interesting to note that 40% of the aggressor mothers are also victims of gender violence. The low frequency of cases of child abuse that are detected by people outside the family is striking.

El maltrato infantil es visto como un tipo de violencia familiar porque es, habitualmente, ejercido por familiares y personas cercanas a los niños. Sobre un mismo niño puede coexistir más de un tipo de violencia y vivir en hogares expuestos a violencia de género. El objetivo de esta investigación es conocer el tipo de maltrato que sufren los menores vistos como víctimas, por orden judicial, y la co-ocurrencia de formas directas e indirectas de violencia, como la exposición a la violencia entre los padres y personas adultas de la familia. Se analizan la relación de la violencia con variables legales, sociodemográficas y de salud del menor, variables de la familia, de salud de los padres y posible victimización de la madre.

MétodoEs un estudio descriptivo y retrospectivo, con datos extraídos de las historias clínico-forenses de menores reconocidos en la UVFI de Bilbao, durante el periodo 2009-2015. La población de estudio es de 675 menores víctimas de maltrato, entre 0-17 años y que fueron explorados de forma individualizada por médicos o psicólogos forenses, por orden judicial. Se ha estudiado, de forma no excluyente, la violencia física, psíquica, violencia sexual, ser testigos de violencia entre adultos de la familia y la polivictimización.

ResultadosDe los menores analizados la violencia más prevalente es el maltrato emocional y ser testigo de violencia entre los adultos de la familia, seguido de la violencia física, la polivictimización y en último lugar de frecuencia sufrir violencia sexual. Hay una elevada co-ocurrencia entre tipos de maltrato, y la violencia hacia los menores y la violencia de género son fenómenos cercanos. Son los niños entre 5 y 11 años los que sufren una mayor victimización. La mayor parte de las denuncias parten de las familias, especialmente de la madre (58%), y el principal denunciado es el padre (47%) seguido de la madre (16%). Es interesante señalar que un 40% de las madres agresoras sufren, a su vez, violencia de género. Llama la atención la baja frecuencia de casos de maltrato infantil que son detectados por personas ajenas a la familia.

Although the abuse of minors is a priority health problem in Europe, only a small proportion of cases are detected and reported. The cases reported usually involve the most severe types of violence, while less severe cases go unreported even when they correspond to situations of chronic violence.1 The culprit is usually a close individual, above all a member of the family of the children.2

Little is known about the rates of abuse of minors at international, national or regional levels. There is no agreement on the different types of abuse of minors, and different classifications have been developed which, together with different research methodologies, hinder the comparison of data and obtaining results.

It is estimated that approximately 15% of minors have suffered some form of violence in Spain.3 The official figures for maltreatment in Spain are contained in the Unified Registry of Child Maltreatment Cases, which records 13,818 boys and girls as victims of maltreatment by a family member in 2015. In order of frequency maltreatment by negligence is the most common form, followed by psychological, physical and sexual abuse.4

Although research tends to focus on specific forms of maltreatment, the most common form is for a single minor to suffer several different types of abuse.5

Some children are the victims of multiple forms of violence within and outside the family; this is “polyvictimisation”.6,7 These children are trapped in spirals of violence or “states of victimisation” with severe affects on their development.6–8

Gender violence and the maltreatment of children share many characteristics, and studies show that there is a close relationship between them9,10 as they share social, community and family factors.1 The children of mothers who suffer violence are 15 times more likely to suffer psychological and physical violence at the hands of their father.2 The same aggressor may attack several members of the family,8 or a victimised mother may project her frustration onto her children.11

Witnessing violence may be considered to be a type of psychological maltreatment12 or a specific type of violence, given the consequences for children's health over the short and long terms.

Children have been considered to be the victims of gender violence since the passing of Law 26/2015, of 28 July, which modified the protection system for minors and adolescents. Nevertheless, there are very few specialised resources to attend to these minors, and the measures used are the same as the ones assigned to their mothers.

Integral Forensic Evaluation Units (IFEU) were created by the application of Law 1/2004 on the integrated care for gender violence victims. The Bilbao IFEU examines, completely and following a judicial order, not only gender violence but all forms of intrafamily violence or violence which is linked to stable forms of relationship. Examinations take place after a judicial order, following the reported suspicion of abuse of a child. Direct examinations of children are undertaken by forensic doctors or psychologists who belong to the Basque Legal Medicine Institute.

ObjectivesThe overall objective of this research is the descriptive analysis of the types of violence suffered by the minors who were examined in a forensic unit following a judicial order. We seek to describe the incidence of each type of violence, concurrent types of violence and their relationship with gender violence, as being a witness to violence is studied as a form of maltreatment. The relationship is examined between the violence suffered by minors and sociodemographic and judicial variables (the reporting and reported individuals), family characteristics (type of family and immigration), the vulnerability of minors based on their previous state of health (physical/psychological diseases/intellectual handicap), the state of health of parents (physical/psychological diseases) and the covictimisation of the mother.

Material and methodsThis is a descriptive retrospective study of a sample of patients, minors (<18 years old) seen in the IFEU from 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2015.

All of the minors were subjected to a psychopathological examination, while only those where there was a suspicion of sexual or physical violence were subjected to a physical examination.

This sample includes all of the child abuse cases analysed in which it was concluded that proof of maltreatment was found. The cases without any direct or indirect indication of maltreatment have been eliminated from the study, together with those suggesting a cause other than violence (such as the instrumentalisation of the child or psychiatric disease in a parent).

The sample underestimates slight physical violence or isolated episodes of violence, as these are seen in other forensic departments.

Child mistreatment was classified in 5 non-mutually exclusive categories.

Physical abuse is defined as any non-accidental action by the parents or tutors that causes physical harm or disease in the child, or which places him at severe risk of suffering this.

Psychological violence: this is chronic verbal hostility in the form of insults, contempt, criticism or threats of abandonment and the constant rejection of initiatives for interaction by the child (from avoidance to confinement or reclusion) by any adult member of the family group.

The National Centre on Child Abuse and Neglect proposed the following definition of sexual abuse: contacts and interactions between a child and an adult, when the adult (the abuser) uses the child to stimulate himself, the child or other individuals. Sexual abuse may also be committed by someone younger than 18 years old if they are significantly older than the child (the victim) or when the abuser is in a position of power or control over the other minor.13

Exposure to gender violence is suffered by those who witness chronic violence between their parents or other family members.14

Polyvictimisation is a typical circumstance in violence when there are different violent scenarios (such as intrafamily and at school, or bullying), or an accumulation of violent experiences in a child's lifetime.15

We excluded mistreatment by negligence from this research for two reasons: the difficulty of defining negligence in operational terms, and the lack of judicial cases in which there are only signs of negligence.

There is no universal definition of child maltreatment by negligence, and nor are the minimum requisites for children's wellbeing standardised in terms of diet, housing and other forms of care. Negligence may be closely associated with very precarious socio-economic conditions. On the other hand, except for situations of severe or very severe negligence, or when it coexists with other forms of violence, when negligence of a child is detected it is normally reported as a situation of risk or neglect (under Organic Law 1/96), and the children's department of the Diputación Foral will automatically take on the role of administrative guardianship without the need for a legal procedure.

Study variablesThe following data were extracted from medical-forensic records for use as variables in analysis.

- 1.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the minor: age and sex.

- 2.

The variable of the vulnerability of the child as defined by their previous state of health: physical or psychological diseases, mental handicap or combination of the same.

- 3.

Legal variables:

- -

The source of the report/reporter: biological father, biological mother, stepfather, stepmother or similar, other family members, school, social services, council, healthcare services or others.

- -

Aggressor/reported individual: biological father, biological mother, stepfather, stepmother or similar, siblings or step-siblings, other family members, more than one aggressor in the family, partner, aggressors within and outside the family.

- -

- 4.

Type of violence: physical violence, psychological violence, sexual violence, witness of violence and multiple victimisations.

- -

The types of violence are not mutually exclusive.

- -

- 5.

Family variables:

- -

Family type: traditional, single parent father, single parent mother, shared custody, reconstructed families, institutionalised children, adopted children.

- -

Immigrants: yes/no.

- -

- 6.

Characteristics of the father: physical diseases, mental diseases.

- 7.

Characteristics of the mother: physical diseases, mental diseases and covictimisation in the violence.

The victims were grouped in 3 age bands: 0–4 years old, 5–11 years old and 12–17 years old.

Data gathering and analysisStatistical analysisThe extracted data were statistically processed using version 18.0 of the SPSS program. Basic descriptive techniques are used for qualitative and quantitative data. Absolute and relative frequencies (percentages) are used in the descriptive study.

For qualitative variables analysis of association used the Chi-squared test, with a 95% level of confidence. Relative risk was used to gauge the strength of associations.

ResultsA total of 675 minors under 18 years old were examined in the Bilbao IFEU, 7 of them incompletely (as they only attended their first appointment).

Examinations of minors per year: 2009 N=102 (23% of cases), 2010 N=93 (25%), 2011 N=96 (23%), 2012 N=88 (18%), 2013 N=73 (19%), 2014 N=132 (29%) and 2015 N=91 (24%).

Three hundred and ninety four were girls (58%) while 281 were boys (42%). The average age of the boys was 10.3±4.3 years old, while for the girls it was 9.6±4 years old (Student's t-test=2.091 (668); P=.037).

Types of violence (not mutually exclusive): physical violence N=313 cases (46%), psychological violence N=430 (63.3%), sexual violence N=184 (27%), witnesses of violence N=428 (63%) and multiple forms of violence N=295 (43.4%).

Source of the report or the reporter: biological mother N=394 (58%), biological father N=127 (18.7%), stepfather/stepmother N=6 (0.9%), school N=24 (3.5%), other family member N=23 (3.4%), social system-council N=21 (3.1%), healthcare system N=7 (1%), and others N=5 (0.74%).

Reported individuals (Table 2): biological father N=319 (47.3%), biological mother N=110 (16.3%) stepfather/stepmother N=86 (12.7%), other family members N=93 (13%), sibling N=9 (1.3%), partner N=22 (3.3%), more than one aggressor in the family N=11 (1.6%).

Immigrant family: N=231 (34%). Immigration is significantly associated with multiple violence (Chi-squared=14.981 [1]; P=.000).

When the mother is the aggressor (N=110) in 43 cases (40%) she in turn is the victim of gender violence. She used physical violence against a minor in N=32 (19% of cases), psychological violence in N=38 (88.4%) and multiple forms of violence in N=23 (13.5%).

The age variable was recorded in 3 clusters: from 0 to 4 years old N=77 (11.4%), from 5 to 11 years old N=321 (47%) and from 12 to 17 years old N=271 (40%), with a Chi-squared significance (for a non-parametric test) of =148.9 (2), P=.000. Table 3 shows the frequency and significance of each type of violence in each age group.

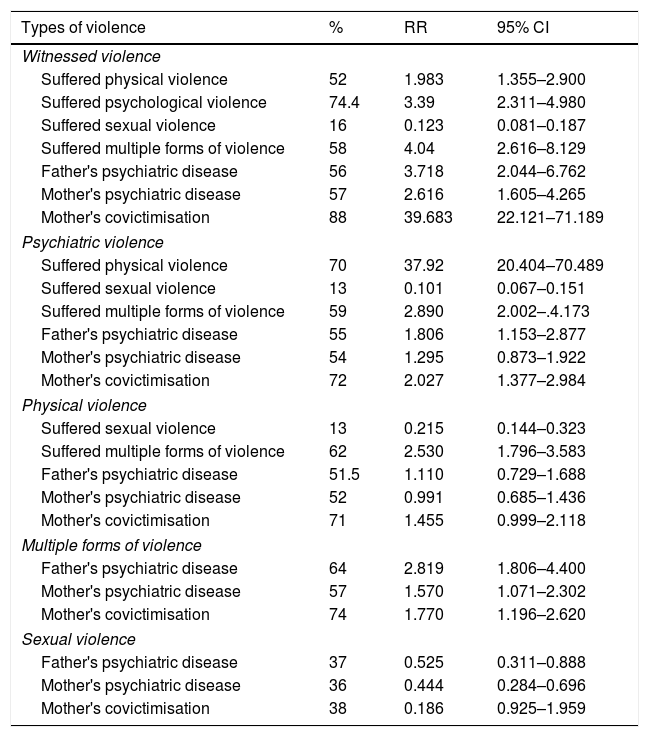

Table 4 shows the probability of several types of violence coexisting and the relationship of this with the factors of the family, the parents or violence between the parents. The first column shows the percentage of cases for each subtype of the main form of violence and the concurrence with other types of violence, the presence of disease in the parents and the covictimisation of the mother. The second column shows the relative risk of each type of violence or parental characteristic, using the subtype of the main type of violence as the reference for comparison in each case. The third column shows the confidence interval in each case at 95%.

DiscussionThis is a forensic sample of minors who were evaluated due to reports of all types of mistreatment.

Bilbao IFEU evaluates family violence. Minors account for 20% of the total number of examinations, with a minimum of 18% in 2012 and a maximum of 25% in the year 2010. Referring a minor or family member for examination is a judicial decision which also sets the terms of the examination. Only a proportion of children are referred for examination, when their mother (or another adult) reports the habitual presence of a minor in a violent context or when they directly suffer adult violence.Analysing child mistreatment in judicial contexts is highly complex, especially less severe psychological or physical violence. Young children are often unaware of the mistreatment and are highly dependent on adults, who use their influence to ensure they report or hide what has happened. The reports of mistreatment of young children are made by a parent, carer or external institution such as a school or medical service. Complementary information is important in cases involving children. If a parent is suspected of causing harm to his child then the information he provides may be partial, biased or contradictory. He may allege that the reports are false or are interpreted erroneously, or an instrumentalisation of the child during highly conflictive processes of separation, with crossed accusations between the parents.

The low percentage of cases in which reports are made by individuals who do not belong to the family is striking, especially those by the health services who see the child at first hand. Higher figures were expected, as shown in the unified Registry of cases of suspected child mistreatment. It is calculated that up to 75% of cases of physical mistreatment may go unnoticed by healthcare professionals, or they may be confused with accidents that are common at this age.16 Professionals may not communicate their suspicion of abuse due to fear of how the parents will react, a reluctance to initiate judicial processes and lack of knowledge of the protocol for action, among other reasons.17

Immigrant families are overrepresented, as in the Basque Autonomous Community they made up 6.08% of the population in the year 2011 (INE). These findings have been repeated in other studies,18 and they may be due to punishment customs and the way children are brought up.

Six of every 10 minors suffer psychological mistreatment (insults, threats or silence, for example), and they witness violence within their family, especially between their parents. These subtypes of violence have been analysed apart.

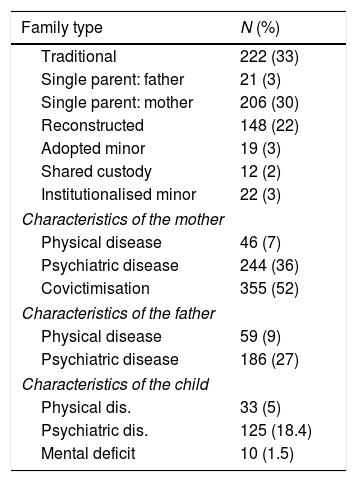

In half of the sample the mother too suffers gender violence (Table 1). This supports the hypothesis that gender violence and child abuse are phenomena that coexist.19

Frequency table: parent characteristics and family type.

| Family type | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Traditional | 222 (33) |

| Single parent: father | 21 (3) |

| Single parent: mother | 206 (30) |

| Reconstructed | 148 (22) |

| Adopted minor | 19 (3) |

| Shared custody | 12 (2) |

| Institutionalised minor | 22 (3) |

| Characteristics of the mother | |

| Physical disease | 46 (7) |

| Psychiatric disease | 244 (36) |

| Covictimisation | 355 (52) |

| Characteristics of the father | |

| Physical disease | 59 (9) |

| Psychiatric disease | 186 (27) |

| Characteristics of the child | |

| Physical dis. | 33 (5) |

| Psychiatric dis. | 125 (18.4) |

| Mental deficit | 10 (1.5) |

Traditional families predominate, followed in incidence by single-parent families (Table 1). It is a complicated matter to analyse this variable, as breakdown of the family does not seem to halt the mistreatment of the children. In judicial contexts when one parent reports the other this may take the form of crossed accusations in highly conflictive separations. In contexts of gender violence a father may attack a child as a means of harming the mother, although in single-parent or reconstructed families it is, in itself, a risk factor for mistreatment of the children.18

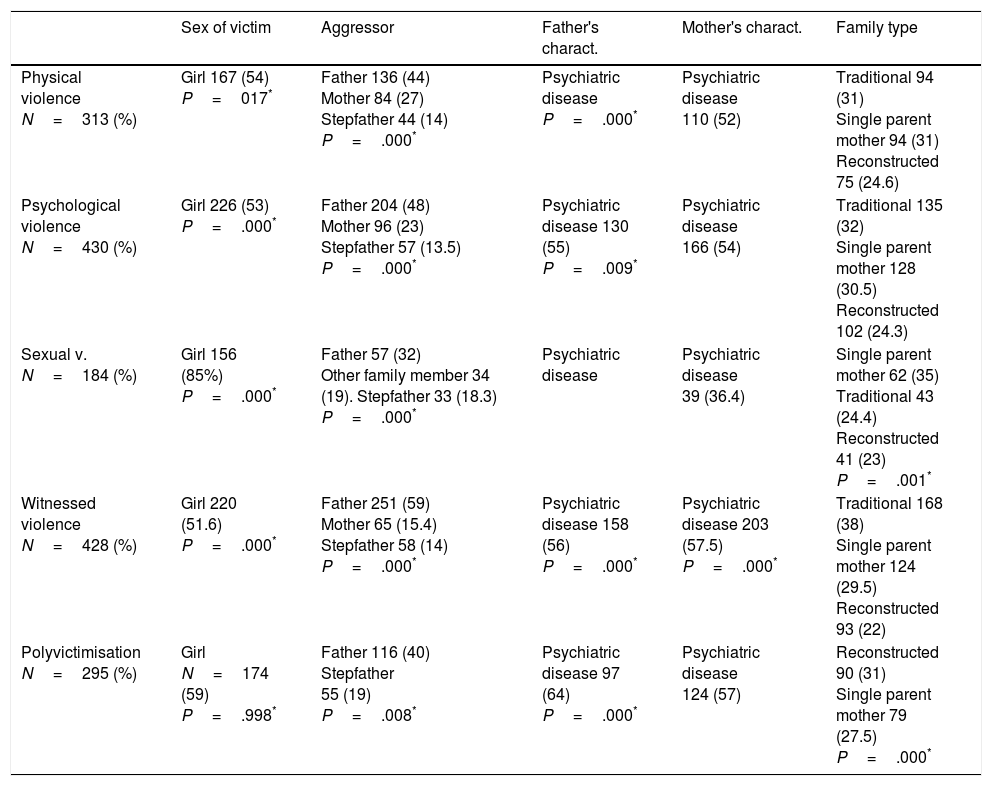

We found a slightly higher proportion of girls among the victims of all forms of violence (Table 2), at a slightly younger average age than the boys. Studies are contradictory about the gender of child victims. Some studies find a higher proportion of girls among the victims of family violence, together with greater emotional impact.20 Other studies identify a higher risk of suffering physical violence in boys, while girls are at greater risk of suffering negligence and sexual violence.21

The relationship between each type of violence and sociodemographic variables, family and parent characteristics.

| Sex of victim | Aggressor | Father's charact. | Mother's charact. | Family type | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical violence N=313 (%) | Girl 167 (54) P=017* | Father 136 (44) Mother 84 (27) Stepfather 44 (14) P=.000* | Psychiatric disease P=.000* | Psychiatric disease 110 (52) | Traditional 94 (31) Single parent mother 94 (31) Reconstructed 75 (24.6) |

| Psychological violence N=430 (%) | Girl 226 (53) P=.000* | Father 204 (48) Mother 96 (23) Stepfather 57 (13.5) P=.000* | Psychiatric disease 130 (55) P=.009* | Psychiatric disease 166 (54) | Traditional 135 (32) Single parent mother 128 (30.5) Reconstructed 102 (24.3) |

| Sexual v. N=184 (%) | Girl 156 (85%) P=.000* | Father 57 (32) Other family member 34 (19). Stepfather 33 (18.3) P=.000* | Psychiatric disease | Psychiatric disease 39 (36.4) | Single parent mother 62 (35) Traditional 43 (24.4) Reconstructed 41 (23) P=.001* |

| Witnessed violence N=428 (%) | Girl 220 (51.6) P=.000* | Father 251 (59) Mother 65 (15.4) Stepfather 58 (14) P=.000* | Psychiatric disease 158 (56) P=.000* | Psychiatric disease 203 (57.5) P=.000* | Traditional 168 (38) Single parent mother 124 (29.5) Reconstructed 93 (22) |

| Polyvictimisation N=295 (%) | Girl N=174 (59) P=.998* | Father 116 (40) Stepfather 55 (19) P=.008* | Psychiatric disease 97 (64) P=.000* | Psychiatric disease 124 (57) | Reconstructed 90 (31) Single parent mother 79 (27.5) P=.000* |

Violence is most often used by fathers, followed by mothers and stepfathers or stepmothers (Table 2), although each type of violence has a specific profile. An important datum is that in a small but significant percentage of cases a mother who suffers abuse mistreats her children in turn, in a displacement of frustration. This phenomenon has been analysed by earlier studies.19

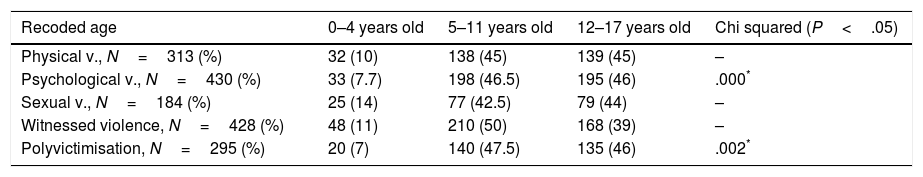

Children aged from 5 to 11 years old suffer a significantly higher percentage of violence (Table 3), and this is similar to the finding of Dutch studies.18 Other studies show that the risk of being a victim of violence increases with age,22 although each kind of violence seems to have a different victim profile.23

Relationship between each type of violence and the recoded age of the minors.

| Recoded age | 0–4 years old | 5–11 years old | 12–17 years old | Chi squared (P<.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical v., N=313 (%) | 32 (10) | 138 (45) | 139 (45) | – |

| Psychological v., N=430 (%) | 33 (7.7) | 198 (46.5) | 195 (46) | .000* |

| Sexual v., N=184 (%) | 25 (14) | 77 (42.5) | 79 (44) | – |

| Witnessed violence, N=428 (%) | 48 (11) | 210 (50) | 168 (39) | – |

| Polyvictimisation, N=295 (%) | 20 (7) | 140 (47.5) | 135 (46) | .002* |

It is clearly difficult to establish pure forms of violence, as there is a significant level of coexistence between different types of abuse, especially physical and psychological violence (Table 4). The children who suffer a form of victimisation were found to be normally exposed to other forms of violence.6–18

Analysis of relative risk for each type of violence and associated factors.

| Types of violence | % | RR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Witnessed violence | |||

| Suffered physical violence | 52 | 1.983 | 1.355–2.900 |

| Suffered psychological violence | 74.4 | 3.39 | 2.311–4.980 |

| Suffered sexual violence | 16 | 0.123 | 0.081–0.187 |

| Suffered multiple forms of violence | 58 | 4.04 | 2.616–8.129 |

| Father's psychiatric disease | 56 | 3.718 | 2.044–6.762 |

| Mother's psychiatric disease | 57 | 2.616 | 1.605–4.265 |

| Mother's covictimisation | 88 | 39.683 | 22.121–71.189 |

| Psychiatric violence | |||

| Suffered physical violence | 70 | 37.92 | 20.404–70.489 |

| Suffered sexual violence | 13 | 0.101 | 0.067–0.151 |

| Suffered multiple forms of violence | 59 | 2.890 | 2.002–.4.173 |

| Father's psychiatric disease | 55 | 1.806 | 1.153–2.877 |

| Mother's psychiatric disease | 54 | 1.295 | 0.873–1.922 |

| Mother's covictimisation | 72 | 2.027 | 1.377–2.984 |

| Physical violence | |||

| Suffered sexual violence | 13 | 0.215 | 0.144–0.323 |

| Suffered multiple forms of violence | 62 | 2.530 | 1.796–3.583 |

| Father's psychiatric disease | 51.5 | 1.110 | 0.729–1.688 |

| Mother's psychiatric disease | 52 | 0.991 | 0.685–1.436 |

| Mother's covictimisation | 71 | 1.455 | 0.999–2.118 |

| Multiple forms of violence | |||

| Father's psychiatric disease | 64 | 2.819 | 1.806–4.400 |

| Mother's psychiatric disease | 57 | 1.570 | 1.071–2.302 |

| Mother's covictimisation | 74 | 1.770 | 1.196–2.620 |

| Sexual violence | |||

| Father's psychiatric disease | 37 | 0.525 | 0.311–0.888 |

| Mother's psychiatric disease | 36 | 0.444 | 0.284–0.696 |

| Mother's covictimisation | 38 | 0.186 | 0.925–1.959 |

Violence between parents seems to create conditions that are suitable for the victimisation of their children within and outside the family itself, as has been identified in studies.8–24 Children who grow up in violent families seem to be cared for and supervised less, as well as socially isolated or unprotected, exposed to high risk environments and multiple forms of violence (Table 4).

These children are immersed in complex realities within the constellation of family violence. Sexual violence seems to be less associated with the factors analysed in this study, and this suggests that there is a need for specific analysis.

Regarding the characteristics of the parents, psychiatric disease in the father (Table 4) increases the risk (almost twice) of the child suffering psychological abuse. It multiplies the risk of their being polyvictimised by 3 times and increases the risk of their being a witness to violence within the family by 4 times. The concept of psychiatric disease includes disorders caused by the consumption of alcohol and drugs, and these have been identified as predictors of violence against children.25

Psychiatric disease in the mother is only significant when children witness violence within the family. The causal link between violence and psychiatric disease is understood to be very different in the case of the father (where it seems to be the cause of violence) than when the mother suffers such disease (where it seems to be the result of violence). Abused women, who are in a precarious emotional situation, may be less protective mothers, ignoring the emotional state of their children or supplying them with less emotional support or being negligent.

A weak association was found between the health characteristics of a child and their experience of violence, while in many studies the psychological or intellectual disability of a child were shown to be strong predictors of violence.26,27

ConclusionWitnessing violence within the family and suffering psychological abuse are the most common forms of violence in our sample, followed by physical violence, multiple violence or polyvictimisation and sexual violence. A high degree of concurrence was found between psychological abuse and exposure to violence within the family on the one hand, and suffering physical and psychological violence on the other.

The data show the close link between gender violence and the abuse of minors, although the father is not always responsible for the violence.

The examination of minors is only a small part of the total amount of medical and forensic investigation, even after clear reports of abuse. This study attempts to make the children trapped in violent scenarios visible.

The low rate of detection of violence by individuals or institutions outside the family itself is striking, given that they are in close contact with minors.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank all of our medical and forensic colleagues in the Bilbao Deputy Directorship of the IVML. This is a shared work, as this shows.

Please cite this article as: Abasolo Telleria AE. Estudio descriptivo del tipo de maltrato que sufren menores evaluados en la Unidad de Valoración Forense Integral de Bizkaia. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2019;45:4–11.

This study has been approved by the IVML Teaching Commission and the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Euskadi (CEIC-e).