Lindsay–Hemenway syndrome, also known as ischaemia of the anterior vestibular artery, was described in 1956 by J.R. Lindsay and W.G. Hemenway, although it was H.F. Schucknecht who discovered its vascular origin. It is a vertiginous syndrome associated with occlusion of the anterior vestibular artery. Ischaemic necrosis causes an acute long-lasting episode of rotatory vertigo. Subsequently, degeneration of the otolithic macula and the accumulation of disperse otoconia in the cupula of the posterior semicircular canal cause benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

Material and methodsA comparative, prospective, multicentre clinical study was conducted from October 2013 to July 2014 at the Ear, Nose and Throat Department of Hospital Regional Dr. Valentín Gómez Farías, Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado, and Hospital General de Zapopan. Patients with Lindsay–Hemenway syndrome were identified and initially treated with vestibular rehabilitation exercises. Patients who did not improve after one month were treated using Semont's liberatory manoeuvre. The clinical outcome of the manoeuvre was classified as total cure, partial cure or no improvement.

ResultsA total of 12 patients were included in the study. Following the first liberatory manoeuvre, 9 patients (75%) presented total cure, 2 patients (16%) presented partial cure and 1 patient (8%) no improvement. Following the second manoeuvre, 2 of the 3 patients with partial cure presented total cure (92%) and one patient still presented no improvement (8%).

DiscussionWe concluded that Semont's liberatory manoeuvre is highly effective in patients presenting Lindsay–Hemenway syndrome.

El síndrome de Lindsay-Hemenway o síndrome de isquemia de la arteria vestibular anterior, fue descrito en 1956 por J.R. Lindsay y W.G. Hemenway, aunque fue H.F. Schuknecht quien descubrió su origen vascular. Consiste en un síndrome vertiginoso asociado a oclusión de la arteria vestibular anterior La necrosis isquémica provoca el gran vértigo rotatorio duradero inicial. Posteriormente, la degeneración de la mácula otolítica y la acumulación de las otoconias dispersas en la cúpula del canal semicircular posterior causan vértigo postural paroxístico benigno.

Material y MétodosSe realizó un estudio clínico, comparativo, prospectivo y multicéntrico durante el periodo comprendido de octubre de 2013 a julio del 2014 en el Servicio de Otorrinolaringología del Hospital Regional Dr. Valentín Gómez Farías del Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado y el Hospital General de Zapopan. Se identificó aquellos pacientes que cursaron con síndrome de Lindsay Hemenway, a los cuales se les otorgó como primer tratamiento, ejercicios de rehabilitación vestibular, aquellos pacientes que después de un mes negaban mejoría, se les aplicó la maniobra liberadora de Semont, El resultado clínico de la maniobra fue catalogado como: curación total, curación parcial y sin mejoría.

ResultadosSe contó con un total de 12 pacientes, en la primera maniobra liberadora, 9 pacientes (75%) presentaron curación total, 2 pacientes (16%) presentaron recuperación parcial y 1 paciente (8%), no presento mejoría en la segunda maniobra liberatoria 2 de los 3 pacientes con curación parcial presentaron curación total (92%), un paciente continuo sin mejoría (8%).

DiscusiónCon nuestros resultados concluimos que la maniobra liberadora de Semont es altamente efectiva en los pacientes que se presentan con síndrome de Lindsay Hemenway.

Lindsay–Hemenway syndrome, or ischaemia of the anterior vestibular artery, is a peripheral vestibular disease caused by ischaemic necrosis of the utricular macula and the superior and horizontal semicircular canals. Ischaemic necrosis initially causes acute, long-lasting rotatory vertigo, degeneration of the otolithic macula and accumulation of disperse otoconia in the cupula of the posterior semicircular canal. When on the decline, this manifests as benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.1

It was described in 1956 by J.R. Lindsay and W.G. Hemenway, although H.F. Schuknecht discovered its vascular origin.2

Particle-liberating or repositioning manoeuvres have been considered the treatment of choice in cases of canalolithiasis or cupulolithiasis, as they aim to move the otoconia out of the posterior semicircular canal to another location in the vestibular labyrinth. They are highly effective in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, in which traces of the macular are deposited in the cupula of the posterior semicircular canal, due to a vascular condition.3

The inner ear comprises a bone labyrinth and a membranous labyrinth. In turn, the labyrinth is divided into an anterior labyrinth formed by the cochlea, and a posterior labyrinth, formed in bone by the vestibular cavity and semicircular canals.4

Vascularisation of the inner ear basically depends on the vertebrobasilar system; the basilar trunk gives rise to the anteroinferior cerebellar artery, which gives rise to the internal auditory artery, which in turn gives rise to the anterior vestibular artery. This artery irrigates the utricular macula and a small portion of the saccule, the ampullae and the membranous walls of the superior and lateral semicircular canals.5

Where the anteroinferior cerebellar artery generates the internal auditory artery, it forms a loop in the inner auditory canal in approximately 70% of cases, entering the canal and then leaving it again; the auditory artery starts at the end of the loop.6

The internal auditory artery in the bottom of the internal auditory canal divides into two branches: the common cochlear artery and the anterior vestibular artery. The common cochlear artery enters the columella and divides into the main cochlear artery and the cochleovestibular artery, the latter of which divides into the posterior vestibular artery and cochlear branches. The cochlear artery irrigates three quarters of the cochlea, including the modiolus; the cochlear branches irrigate the basal quarter of the cochlea and the adjacent modiolus. The anterior vestibular irrigates the utricular macula and a small part of the saccule and also the ampullary crest of the superior and horizontal semicircular canals, the upper face of the utricular bags and saccule. The posterior vestibular irrigates the macula of the saccule, the inferior face of both utricles, the saccule, the crest and the posterior semicircular canal. All branches are terminal, so an interruption in flow causes a rapid structural decline.7

Ischaemia is likely to produce necrosis of the utricular macula, thus releasing otoconia that are projected to the ampulla of the posterior semicircular canal, causing cupulolithiasis.8

The symptoms are characterised by two phases: the first is an episode of acute, disabling vertigo that can last for days, at which time the doctor administers treatment to reduce the symptoms. Subsequently, however, the second phase is characterised by benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) that lasts for days or weeks, which can reappear often, associated with reduced or no response in caloric tests.

Diagnosis: In the first phase it can be mistaken for vestibular neuronitis or any other condition that involves days of disabling acute vertigo. The symptoms that result from the ischaemia of some portions of the labyrinth are highly sensitive, but specificity is low, due to the large variety of conditions that present similar symptoms but with a different aetiology.

Regarding the second phase of the symptoms, its sensitivity and specificity are greater, as in this case the vertigo is not long-lasting and is associated with head movements, which, together with other specific characteristics, is highly suggestive of BPPV. However, additional studies are required to identify the origin and topography, including diagnostic vestibular manoeuvres such as those described by Dix and Hallpike. When the diagnosis of BPPV is confirmed, caloric testing is required. Hyporeactivity or lack of response is highly suggestive of a labyrinth lesion and could lead to a specialist diagnosis of Lindsay–Hemenway syndrome.9

Pardal Refoyo et al. reported that in 98 patients diagnosed with BPPV, 16% presented ischaemia of the anterior vestibular artery.1

Several manoeuvres have been described for the medical treatment of BPPV and canalolithiasis, with the first described by Semont, Freyss and Vitte in 1988, followed by the Epley repositioning manoeuvre in 1992.10 In 1994, Brandt, Steddin and Daroff completed the treatment by describing repositioning and rehabilitation exercises to be performed at home.14

Many authors have made changes to the original techniques, with reports of success in different institutions. Repositioning manoeuvres are considered the most effective and less costly method for the management of canalolithiasis.11

Material and methodsA case series was performed from October 2013 to July 2014.

It was conducted at the Ear, Nose and Throat and Head and Neck Surgery Department of Hospital Regional Dr. Valentín Gómez Farías, Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado, in Zapopan, Jalisco, Mexico and Hospital General de Zapopan, Jalisco, Mexico.

A full clinical history was taken and patients were invited to participate in the study after granting informed consent.

Patients with Lindsay–Hemenway syndrome were identified based on the following criteria:

- 1.

History of intense, acute vertigo, with a duration of hours, followed by episodes of vertigo associated with head movements, with no cochlear symptoms.

- 2.

Positive Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre.

- 3.

Absence or reduction of caloric response.

The inclusion criteria were: patients who lived in the urban area where the study was conducted, who had not previously been medicated, who had an electronystagmography interpreted by specialist personnel from both hospitals’ audiology department, who had absence or reduction of caloric response in the affected ear and who agreed to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria: Recent cervical vertebral fracture, prolapse of cervical intervertebral disc, rotational compression of cervical vertebral arteries, and failure to provide informed consent in writing.

The medical treatment prescribed to all the patients presenting disabling acute vertigo was diphenidol 40mg tablets, three times a day with dose reduction every third day, followed by a series of vestibular rehabilitation exercises described by Cawthorne and Cooksey.12,13 They start with the patient seated and making eye movements, followed by head movements, and then the same exercises with the patient standing, followed by attempting to pick an object up from the floor and stand. These exercises were to be performed for 20min three times a day for a month. None of the patients was treated for ischaemia. The patients who improved after the vestibular rehabilitation exercises were discharged. The rest underwent the diagnostic Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre as follows:

With the patient seated on the examination table, the patient's head was held in both hands, turned to the right at a 45° angle to the sagittal plane, with the patient looking at a point on the examiner's body. The patient then lay down and was examined for nystagmus. This was followed by the same procedure on the contralateral side. A test was positive if nystagmus was triggered. The affected side was the side towards which the nystagmus began.

Once the suspected diagnosis was confirmed by the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre, caloric tests were performed to confirm the reduction in the vestibular response of the affected side.

In no case were imaging or laboratory tests performed to confirm ischaemia or necrosis of the labyrinth.

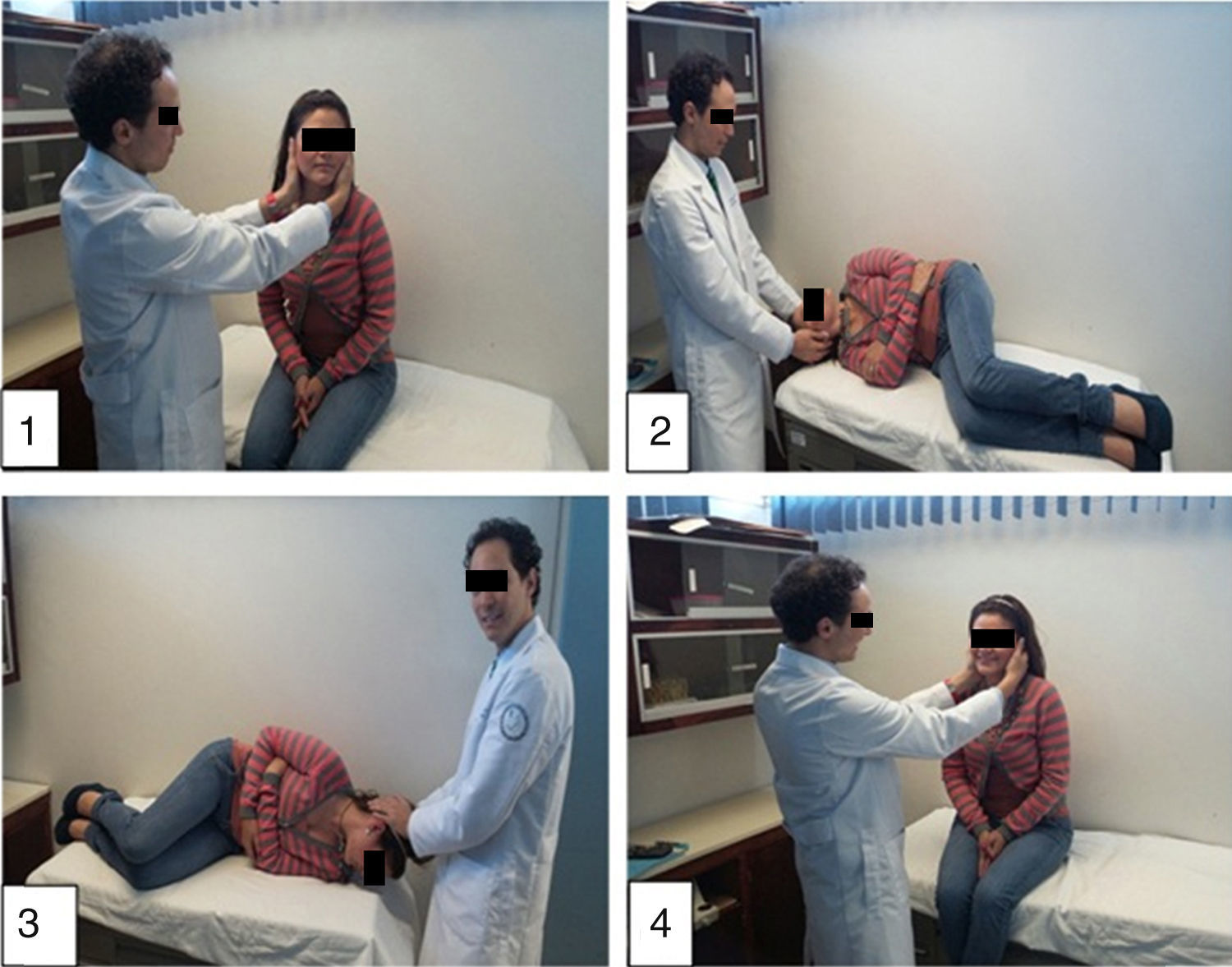

The patients then underwent Semont's liberating manoeuvre.

(See Images 1–4)

- 1.

With the patient seated on the examination table with his/her legs hanging, the head is turned 45° towards the healthy ear.

- 2.

The patient was then asked to lie on his/her side with a neck extension of approximately 105°, towards the affected side, for 3min.

- 3.

The patient was rapidly taken to the same position on the opposite site, turning by 195° face downwards, resting on the contralateral ear for 3min.

- 4.

Initial position.

Image 1. Seat the patient on the examination table with his/her legs hanging and turn the head 45° towards the healthy ear. Image 2. Place the patient in a lateral decubitus position with a neck extension of approx. 105° towards the affected side, for 3min. Image 3. Quickly move the patient to the same position on the opposite site, turning by 195° face downwards, resting on the contralateral ear for 3min. Image 4. Initial position.

The clinical outcome was immediately re-assessed after this manoeuvre with the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre.

The result of the manoeuvre was classified as:

- •

Total cure: Patients who did not present nystagmus after Dix-Hallpike and with improved vertigo.

- •

Partial cure: Patient who continued with vertigo but did not present nystagmus with Dix-Hallpike.

- •

No improvement: Patients who continued with vertigo and nystagmus with the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre.

The patients who presented total cure after the liberating manoeuvre were discharged. Patients with partial cure or no improvement were told to rest without medication and return 7 days after the manoeuvre was applied. Dix-Hallpike-positive patients underwent the liberating manoeuvre for a second time. The results were reported in the same manner. All the data were tabulated and the results analysed with the EPI-Info programme, Version 3.5.4 with the help of the UVM Medical Faculty's biostatistics department on the Zapopan campus.

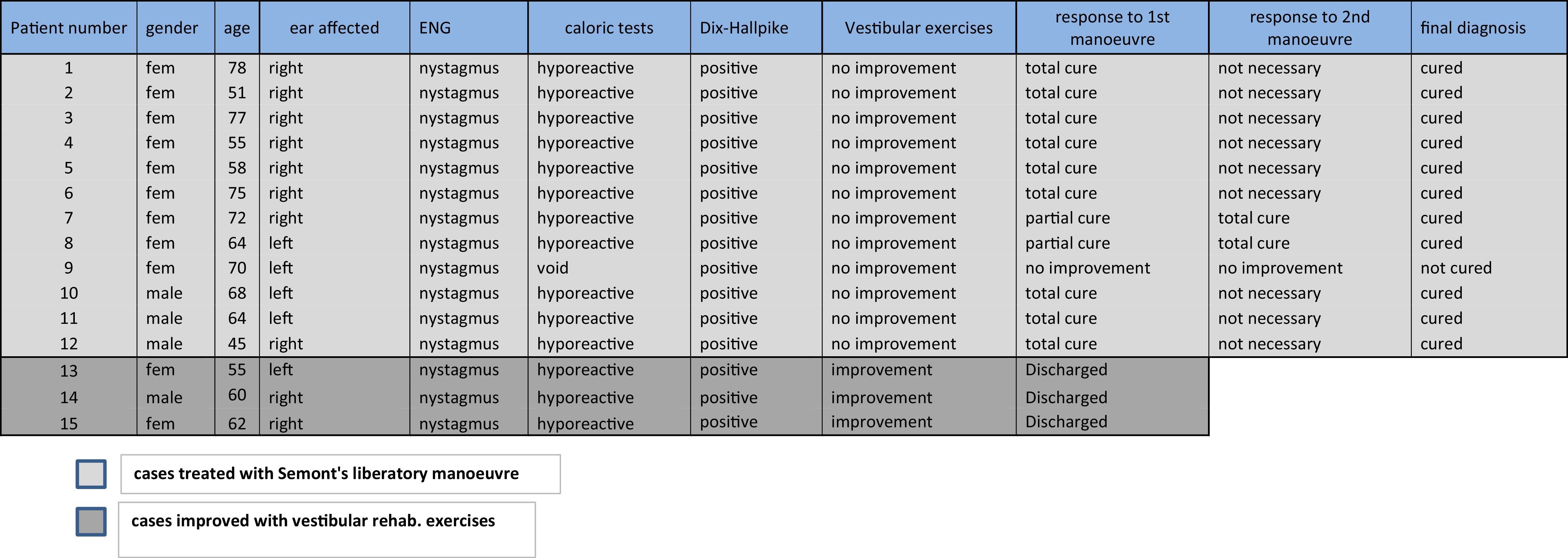

ResultsThe total sample comprised 15 patients. Mean age of onset was 65 years with a range from 45 to 78 years. The right ear was affected in 10 patients (66.6%) and the left in 5 cases (33.3%). 11 patients (73.3%) were female and 4 (26.6%) male.

They received initial treatment with vestibular rehabilitation exercises for one month. 3 patients (20%) referred total cure with negative Dix-Hallpike and were discharged; 12 (80%) persisted with the symptoms and presented unilateral positive Dix-Hallpike. 9 of these 12 patients were women (75%) and 3 men (25%), representing a 3:1 ratio. During the first liberating manoeuvre, 9 patients (75%) presented total cure, 2 (16%) presented partial cure and 1 presented no improvement (8%).

The 3 remaining patients without total cure underwent a second liberating manoeuvre, of which two presented total cure. When added to the 9 patients with total cure after the first manoeuvre, they total 11 patients (91.66%). Only 1 patient continued to present no improvement (8.33%) (See Table 1).

The statistical analysis was based on inferential statistics. To compare the efficacy of Semont's manoeuvre with the vestibular exercises, we used the parametric Mann–Whitney U-test for independent groups, obtaining p=0.001, which is statistically significant in favour of Semont's manoeuvre.

Contingency tables were used to find the difference between right and left ear; it was not statistically significant.

DiscussionThis study showed that cupulolithiasis, caused by ischaemic of the anterior vestibular artery, which generates benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, Lindsay–Hemenway syndrome, could be treated with liberating manoeuvres, an alternative treatment for the condition with an excellent outcome. To prevent variability in the results following application of the proposed treatment by healthcare professionals, the diagnosis must be precise and accurate, ruling out other conditions, and the manoeuvres must be performed exactly as described in this article.

Semont reported 93% effectiveness, with a 4% recurrence rate at 8 years for the treatment of cupulolithiasis. The success rate in our study is 91.66%, very similar to the results obtained by Semont.

In Mexico, due to the low diagnostic rate of this condition, the initial treatment provided is vestibular sedatives, widely known and used by primary and specialist care. The patients will subsequently present a second episode of vertigo related to head movements, for which specialists rarely perform liberating manoeuvres as the only treatment.

Our study was limited by a lack at both hospitals of the technology required to show ischaemia of the vestibular artery. Another limitation when evaluating the efficacy of the vestibular rehabilitation exercises is patient non-compliance and patients’ lack of faith in the success of the exercises.

Cupulolithiasis remains an attractive concept for explaining the physiopathology of BPPV caused by Lindsay–Hemenway syndrome.

Semont's liberating manoeuvre is particularly effective in this case as it is primarily indicated in cases of cupulolithiasis and not canalolithiasis, which is less common in this syndrome. Both conditions, however, cause BPPV. We can find no references directly reporting the effectiveness of Semont's manoeuvre in treating Lindsay–Hemenway syndrome.

The results of the study suggest that Semont's manoeuvre is highly effective in the treatment of Lindsay–Hemenway syndrome.

Ethical disclosureProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.