The rise in consultations for asthma or wheezing in primary and hospital care in recent years suggests a progressive increase in the prevalence of this disease, causing morbidity and considerable medical expenses. However, in Honduras no information about the prevalence of asthma and its trends is available. The aim was to determine the prevalence of asthma in the school-aged and adolescent population in several coastal communities in Honduras.

MethodsWe performed a multi-centre, observational, cross-sectional study, for which we took a random sample of 805 school-aged children and adolescents between the ages of 6 and 17 years residing in the coastal communities of Coxen Hole, French Harbour, Los Fuertes, Sandy Bay, Punta Gorda, Travesía and Bajamar. The prevalence and severity of asthma were determined using the validated International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) questionnaire answered by the child's parents. Point and cumulative prevalence were estimated, stratified by ethnic group, community, sex, and family history of asthma.

ResultsWe found an overall prevalence of wheezing in the past of 40.5% (95% CI 37.1, 43.9); of wheezing in the last 12 months of 28.0% (95% CI 24.9, 31.1); and have or have had asthma of 31.7% (95% CI 28.5, 34.9). The community with the highest prevalence was Bajamar with 51.0% (95% CI 44.0, 58.0), and in general, the Garifuna ethnic group with 36.5% (95% CI 31.0, 41.9).

ConclusionThe prevalence of asthma was higher than in other Latin American regions, with the most cases in participants of African descent, and those with a family history of asthma. The results will provide important data on asthma in Honduras and will contribute to the identification of risk groups.

El aumento de consultas por asma o sibilancias en atención primaria y hospitalaria en los últimos años sugiere un aumento progresivo de la prevalencia de esta enfermedad, causando morbilidad y gastos sanitarios considerables. Sin embargo, en Honduras no hay información acerca de la prevalencia de asma y su tendencia. El objetivo fue determinar la prevalencia de asma en la población escolar y adolescente en diversas comunidades costeras de Honduras.

MétodosRealizamos un estudio multicéntrico, observacional, transversal, para lo cual tomamos una muestra aleatoria de 805 menores escolares y adolescentes entre las edades de 6 a 17 años en las comunidades costeras de Coxen Hole, French Harbour, Los Fuertes, Sandy Bay, Punta Gorda, Travesía y Bajamar. Se determinaron la prevalencia y severidad de asma mediante el cuestionario validado Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) contestado por los padres del niño. Se estimaron prevalencia puntual y acumulada estratificando por grupo étnico, área, sexo e historia familiar de asma.

ResultadosEncontramos una prevalencia global de sibilancias en el pasado de 40.5% (IC95% 37.1, 43.9); de sibilancias en los últimos 12 meses de 28.0% (IC95% 24.9, 31.1); y de tener o haber tenido asma de 31.7% (IC95% 28.5, 34.9). La comunidad con mayor prevalencia fue Bajamar con 51.0% (IC95% 44.0, 58.0), y en general, la etnia Garífuna con 36.5% (IC95% 31.0, 41.9).

ConclusiónLa prevalencia de asma fue considerablemente más alta que en otras regiones de Latinoamérica, encontrándose la mayoría de casos en participantes de etnias afrodescendientes y con el antecedente familiar de asma. Los resultados proporcionarán datos importantes del asma en Honduras y contribuirá a la identificación de grupos en riesgo.

Asthma is a heterogeneous and multifactorial disease, generally characterised by chronic inflammation of the respiratory tract, which is defined by a history of respiratory symptoms such as wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and cough, which vary over time and in intensity, along with a varying limitation in the expiratory air flow.1 It is present in all countries worldwide regardless of their degree of development, although more than 80% of asthma deaths take place in low and mid-low income countries.2 The prevalence varies according to geographic region, climate, lifestyle, and the economic development of each region. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that it affects 300 million people and that it is still a cause of death worldwide.3

Due to the increase in the prevalence of asthma, treatment costs at the public health level have increased, reflecting an increased use of economic resources while at the same time having a social impact by being an important cause of school absenteeism.4,5 This is why several epidemiological studies have been conducted in Latin America and around the world, the most important being the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC), which revealed a prevalence of between 5% and 20% of the child population.6 This has awoken an enormous interest in identifying factors influencing the prevalence of this disease which in Honduras largely affects the paediatric population, where there are not enough up-to-date studies that allow the impact it has on the healthcare system and its socioeconomic impact to be determined.

The main objective of this research study was to compare the prevalence of asthma in the school-aged and adolescent population from 6 to 17 years of age among several communities on Roatán Island, located off the Caribbean coast in Honduras, and two ethnic coastal communities in the city of Puerto Cortés. To do this we used the standardised and validated ISAAC survey that includes questions related to asthma symptomatology and severity as answered by the parents or guardians.

The ethnic composition of the island is diverse, including people of Afro-English, Garifuna, Miskito, Ladino, and mixed-race descent. Some of the communities have a low socioeconomic level in addition to other factors that could be related to asthma, such as a high incidence of medical appointments for respiratory illnesses in the different public health units. To our knowledge, to date there have been no asthma prevalence studies in the coastal communities analysed in this work.

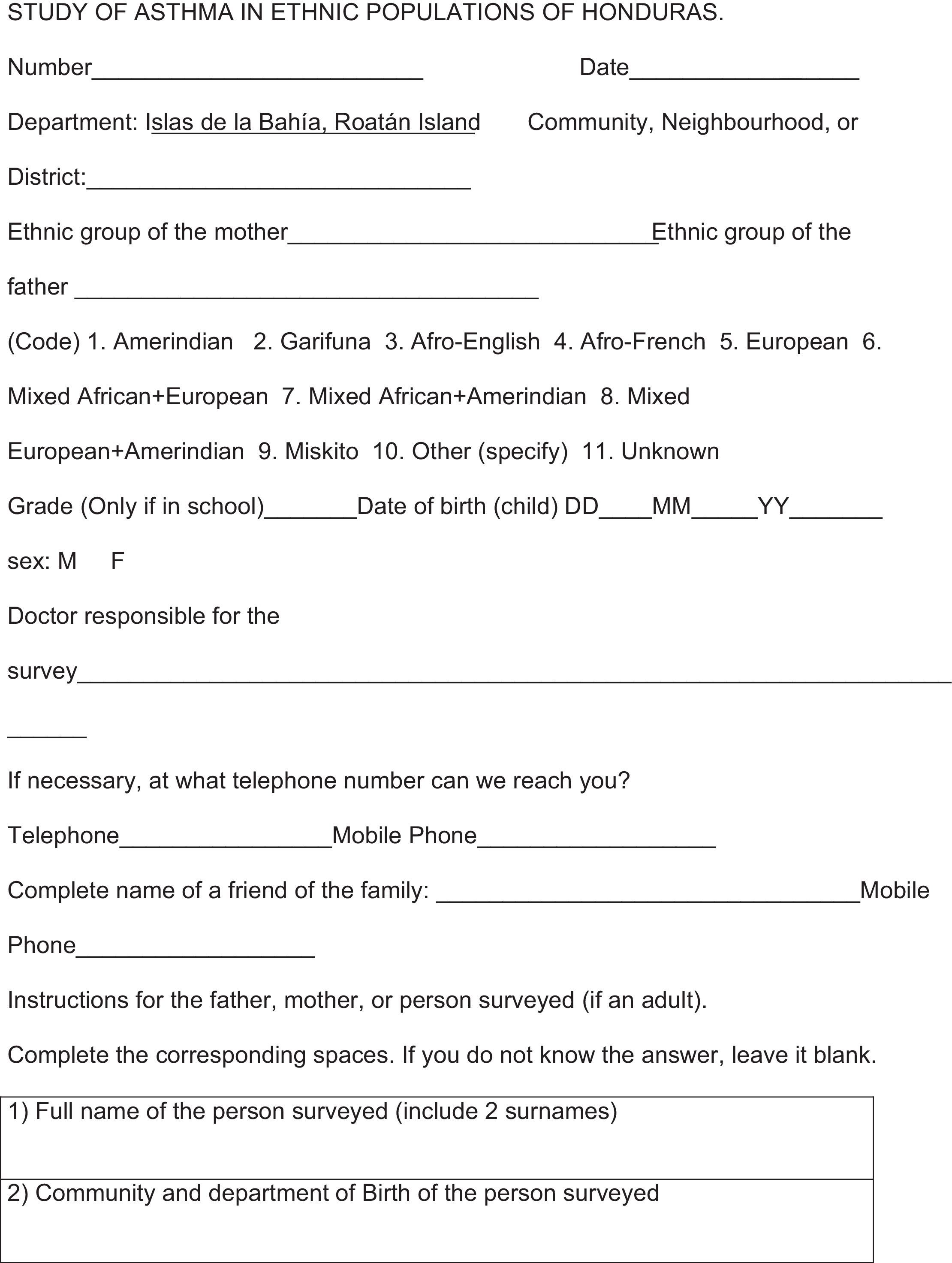

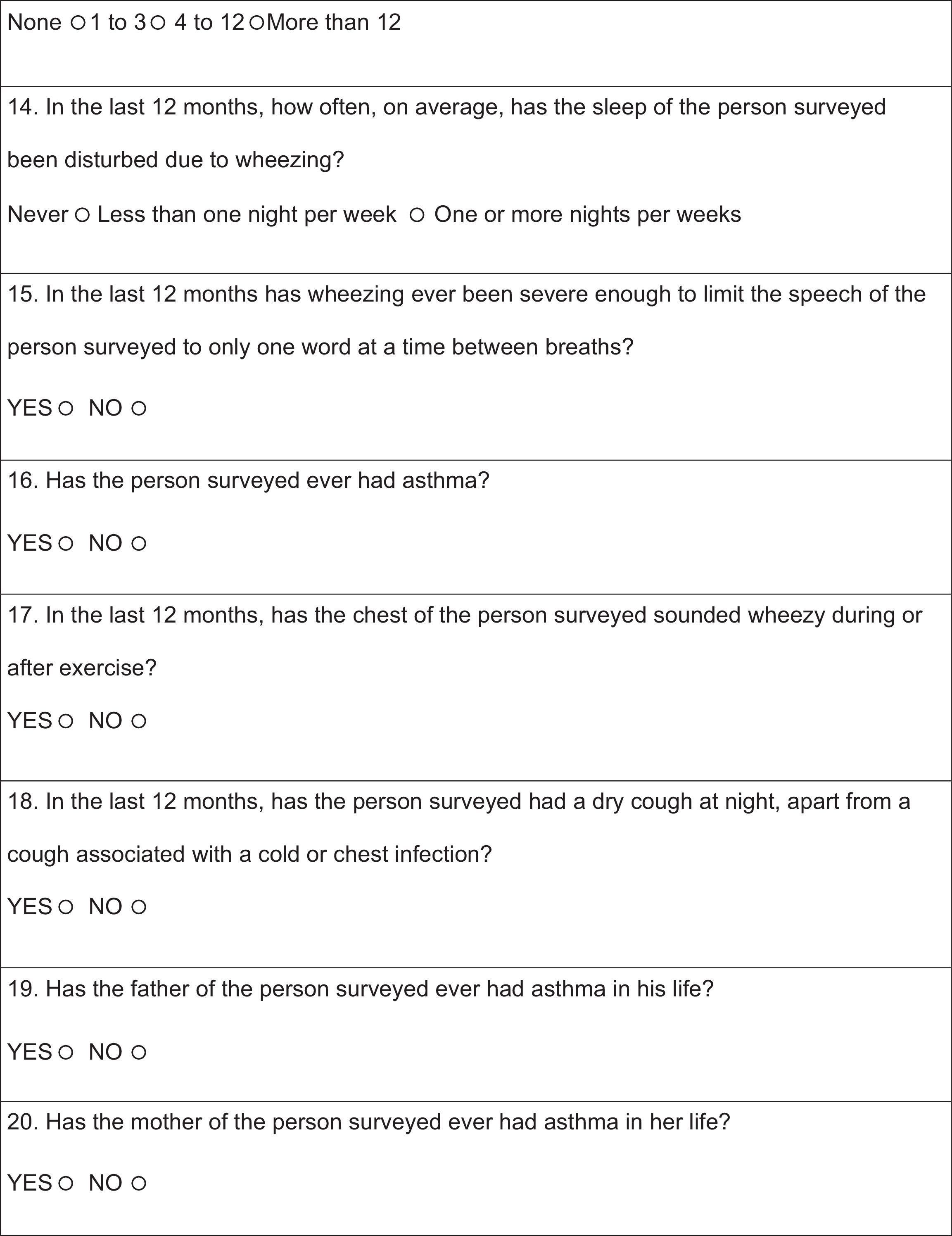

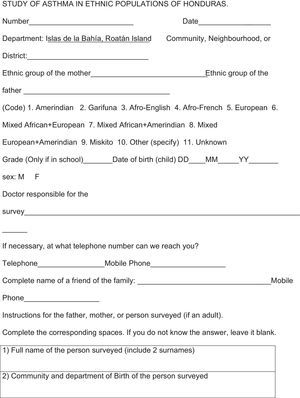

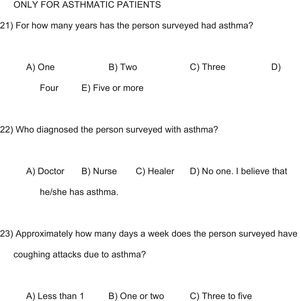

Materials and methodsWe have conducted a multi-centre, observational, cross-sectional study in coastal Caribbean communities of the Republic of Honduras using the validated and standardised ISAAC questionnaire in Spanish (Appendix 1).7

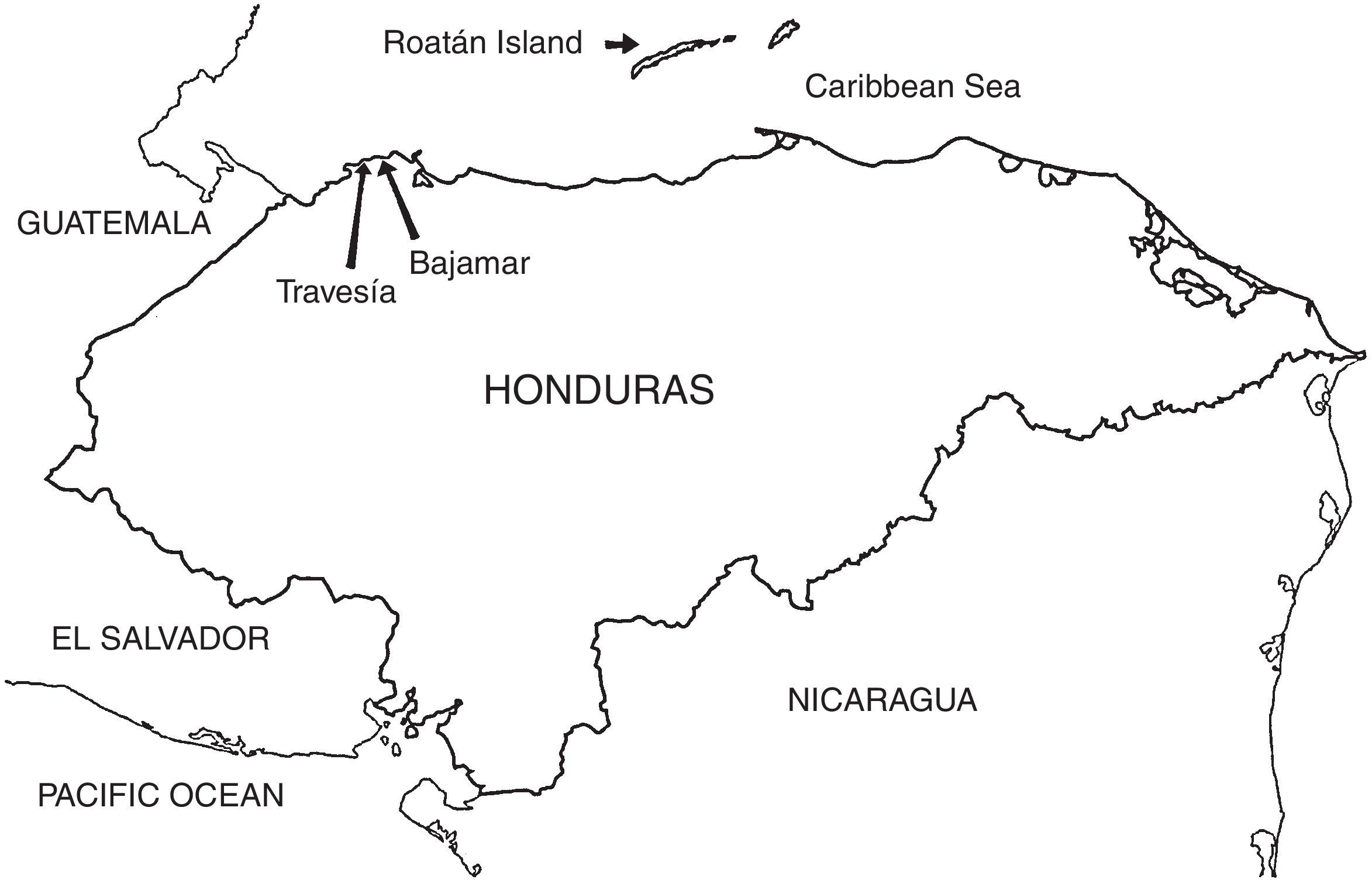

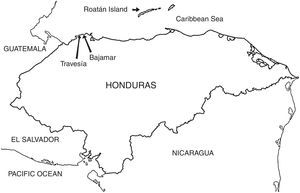

Population and sampleThe communities studied were Coxen Hole, French Harbour, Los Fuertes, Sandy Bay, and Punta Gorda, all included within the municipality of Roatán, Islas de la Bahía; and the communities of Travesía and Bajamar located on the continental coast, in the city of Puerto Cortés (Fig. 1). These communities are mainly comprised of more or less pure ethnic groups, as well as Ladinos. The term Ladino is derived from the word “Latino” and is widely used in Latin America to refer to the mixed-race population with varying and indeterminate degrees of Spanish, Native American, and African contributions.8 Furthermore we use here the term “mixed-race” to refer to any cases in which the father and mother belong to different ethnic groups.

The ethnic groups studied were: (1) Afro-English. They are mainly located in the departments of the Islas de la Bahía (in our study they were mainly found in the communities of French Harbour and Sandy Bay) and Atlántida.9 (2) Garifuna (Garinagu in the plural). This is an ethnic group of African descent and the largest in the Honduran Caribbean with more than 50 communities along the coast.10 The communities of Punta Gorda, Bajamar, and Travesía are predominantly Garifuna. Recent studies with mitochondrial markers show a predominance of African haplogroups (77%) in this ethnic group.11 (3) The Miskitos are an indigenous ethnic group from Central America, currently located in Honduras and Nicaragua.9

Bajamar and Travesía were easily sampled house-by-house in 2009, and for the rest of the communities (Roatán), a representative sample was calculated and the surveys randomly distributed in the schools. The database of the Honduras Ministry of Education for the period from May to July 2015 was taken as a reference for these last samples. In the end, a sample of 805 participants between the ages of 6 and 17 years old was obtained. The questionnaire used corresponded to the first phase of the ISAAC program designed to calculate the prevalence of asthma.12 The research objectives and procedures were explained to those surveyed and their parents or guardians, from whom informed consent was obtained prior to administering the survey.

The study was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee (IEC) of the Universidad Católica de Honduras, San Pedro and San Pablo Campus. In preparation for participating in this research project, the investigators took the “Protecting Human Subject Research Participants” course by the National Institutes of Health.13

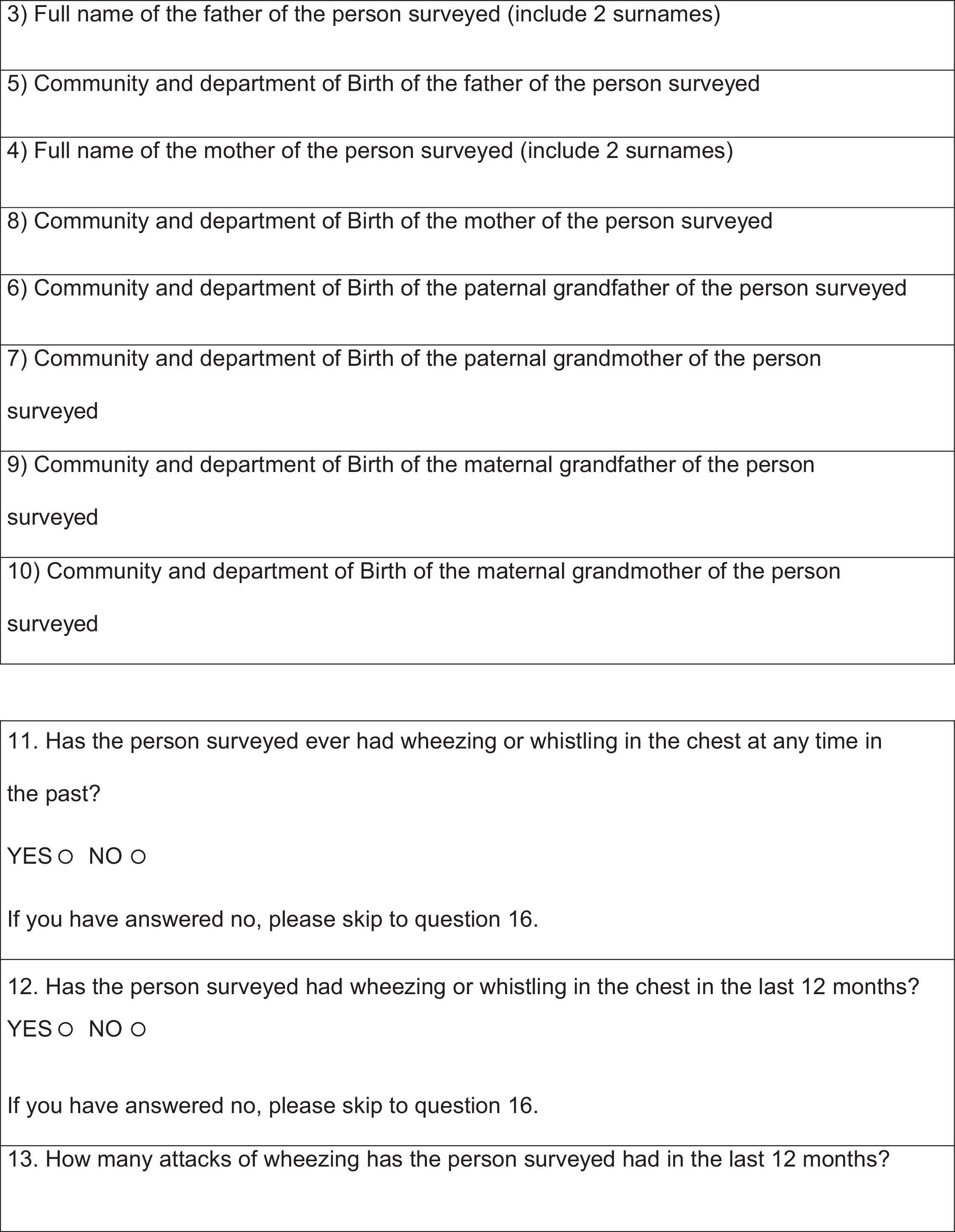

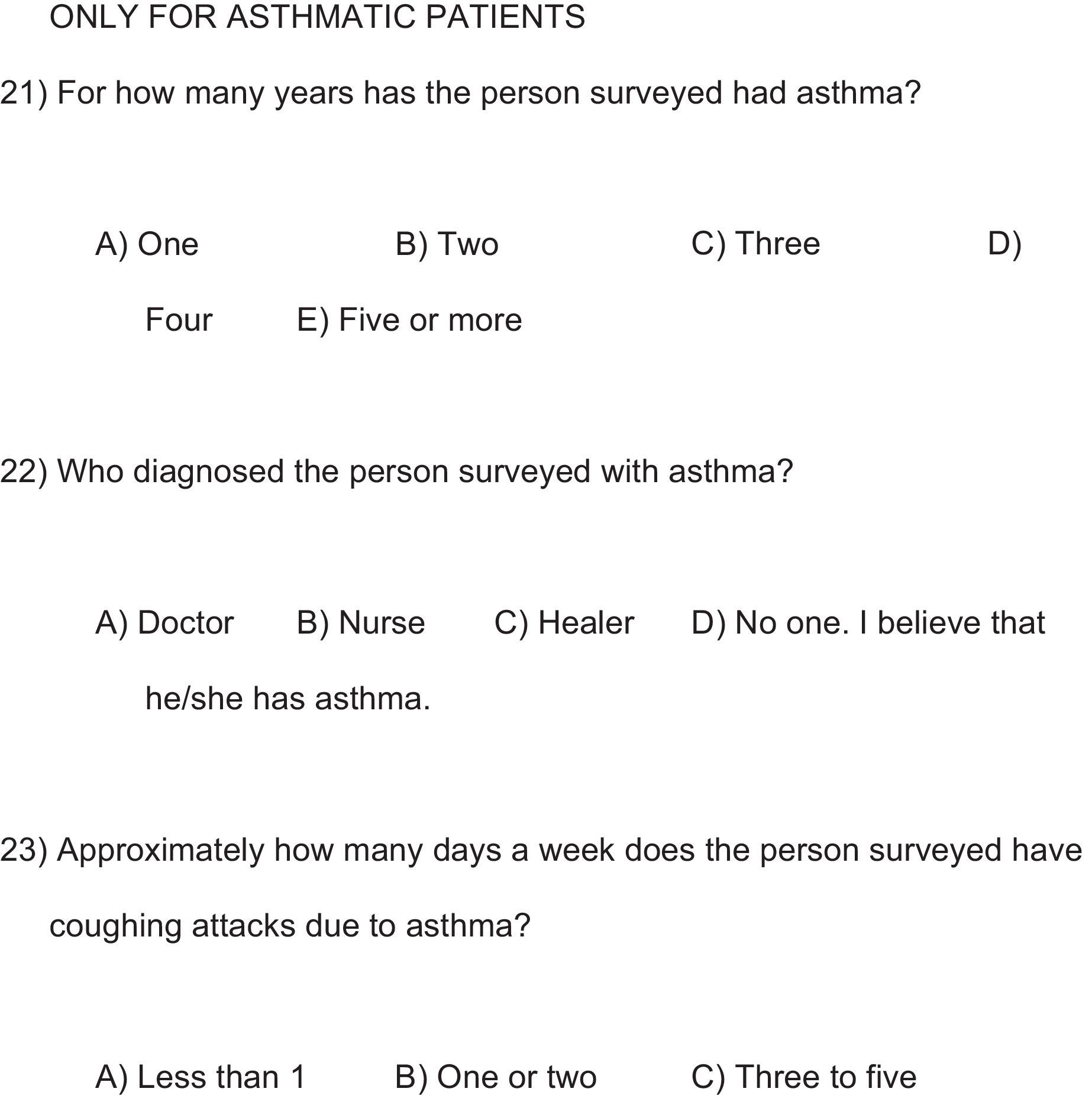

Statistical methodsThe lifelong cumulative prevalence was obtained by dividing the number of cases who had had asthma (ISAAC question 11) or wheezing in the chest at some point in their life (question 16) by the sample total; and the point prevalence was obtained by dividing the number of cases of wheezing in the chest in the last 12 months (question 12) by the total. Asthma severity was determined by the number of episodes of wheezing in one year (question 13), the number of times woken at night by wheezing (question 14), and difficulty speaking due to wheezing (question 15).14,15

The prevalence of asthma between ethnic groups and between communities and the probability of asthma in a child with an asthmatic father or mother were compared using Chi Squared tests (X2) and Fisher's exact test (FET), and the 95% confidence intervals were calculated. An alpha (α) value of 0.05 was used for all comparisons. Microsoft Excel 2010 and the IBM SPSS Statistics package 22 were used to prepare the tables and the statistics calculations.

ResultsSample characteristicsA total of 805 students participated in the study, coastal community residents ranging in age from 6 to 17 years old with a mean age of 9.8 years. The participants were predominantly female (55.9%). In Travesía and Bajamar there was greater asthma prevalence in females, with 60% and 59% respectively; Los Fuertes had similar proportions (50%), and the prevalence was predominantly male in the rest of the communities. However, the differences between communities were not statistically significant.

The participants were in grades 1–12. The participating ethnic groups were Garifuna (37.1%), Ladino (31.2%), mixed-race (25.5%), Afro-English (4.2%), and others (2.0%). The Miskitos were included in others as the sample was small and only 6 participated.

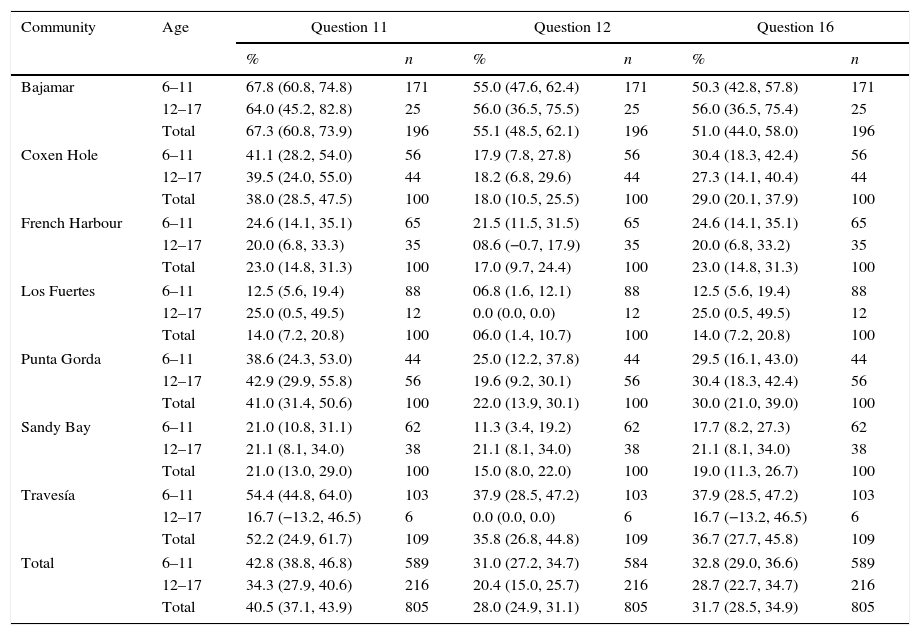

Prevalence of wheezing and asthmaThe overall cumulative lifelong prevalence of wheezing (including all the age groups from all the communities studied) measured by question 11 was 40.5%, with the highest value recorded in Bajamar (67.3%) and the lowest in Los Fuertes (14.0%). The overall point prevalence of wheezing (in the last 12 months) was 28.0%, the highest in Bajamar (55.1%) and the lowest in Los Fuertes (6.0%). The overall prevalence of having or having had asthma was 31.7%, highest in the community of Bajamar (51.0%) and lowest in the community of Los Fuertes (14.0%). A significant difference was found in the asthma prevalence between the community of Bajamar and the rest of the communities (p<0.05, X2 and FET); as well as in Travesía, except when comparing it with Punta Gorda and Coxen Hole (p>0.05, X2 and FET); however, in Punta Gorda and Coxen Hole a higher prevalence was observed in comparison with Los Fuertes (p<0.05, X2 and FET). The prevalence in the different communities divided into age groups and the totals is shown in Table 1.

Prevalence of asthma by community.

| Community | Age | Question 11 | Question 12 | Question 16 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | % | n | ||

| Bajamar | 6–11 | 67.8 (60.8, 74.8) | 171 | 55.0 (47.6, 62.4) | 171 | 50.3 (42.8, 57.8) | 171 |

| 12–17 | 64.0 (45.2, 82.8) | 25 | 56.0 (36.5, 75.5) | 25 | 56.0 (36.5, 75.4) | 25 | |

| Total | 67.3 (60.8, 73.9) | 196 | 55.1 (48.5, 62.1) | 196 | 51.0 (44.0, 58.0) | 196 | |

| Coxen Hole | 6–11 | 41.1 (28.2, 54.0) | 56 | 17.9 (7.8, 27.8) | 56 | 30.4 (18.3, 42.4) | 56 |

| 12–17 | 39.5 (24.0, 55.0) | 44 | 18.2 (6.8, 29.6) | 44 | 27.3 (14.1, 40.4) | 44 | |

| Total | 38.0 (28.5, 47.5) | 100 | 18.0 (10.5, 25.5) | 100 | 29.0 (20.1, 37.9) | 100 | |

| French Harbour | 6–11 | 24.6 (14.1, 35.1) | 65 | 21.5 (11.5, 31.5) | 65 | 24.6 (14.1, 35.1) | 65 |

| 12–17 | 20.0 (6.8, 33.3) | 35 | 08.6 (−0.7, 17.9) | 35 | 20.0 (6.8, 33.2) | 35 | |

| Total | 23.0 (14.8, 31.3) | 100 | 17.0 (9.7, 24.4) | 100 | 23.0 (14.8, 31.3) | 100 | |

| Los Fuertes | 6–11 | 12.5 (5.6, 19.4) | 88 | 06.8 (1.6, 12.1) | 88 | 12.5 (5.6, 19.4) | 88 |

| 12–17 | 25.0 (0.5, 49.5) | 12 | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 12 | 25.0 (0.5, 49.5) | 12 | |

| Total | 14.0 (7.2, 20.8) | 100 | 06.0 (1.4, 10.7) | 100 | 14.0 (7.2, 20.8) | 100 | |

| Punta Gorda | 6–11 | 38.6 (24.3, 53.0) | 44 | 25.0 (12.2, 37.8) | 44 | 29.5 (16.1, 43.0) | 44 |

| 12–17 | 42.9 (29.9, 55.8) | 56 | 19.6 (9.2, 30.1) | 56 | 30.4 (18.3, 42.4) | 56 | |

| Total | 41.0 (31.4, 50.6) | 100 | 22.0 (13.9, 30.1) | 100 | 30.0 (21.0, 39.0) | 100 | |

| Sandy Bay | 6–11 | 21.0 (10.8, 31.1) | 62 | 11.3 (3.4, 19.2) | 62 | 17.7 (8.2, 27.3) | 62 |

| 12–17 | 21.1 (8.1, 34.0) | 38 | 21.1 (8.1, 34.0) | 38 | 21.1 (8.1, 34.0) | 38 | |

| Total | 21.0 (13.0, 29.0) | 100 | 15.0 (8.0, 22.0) | 100 | 19.0 (11.3, 26.7) | 100 | |

| Travesía | 6–11 | 54.4 (44.8, 64.0) | 103 | 37.9 (28.5, 47.2) | 103 | 37.9 (28.5, 47.2) | 103 |

| 12–17 | 16.7 (−13.2, 46.5) | 6 | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 6 | 16.7 (−13.2, 46.5) | 6 | |

| Total | 52.2 (24.9, 61.7) | 109 | 35.8 (26.8, 44.8) | 109 | 36.7 (27.7, 45.8) | 109 | |

| Total | 6–11 | 42.8 (38.8, 46.8) | 589 | 31.0 (27.2, 34.7) | 584 | 32.8 (29.0, 36.6) | 589 |

| 12–17 | 34.3 (27.9, 40.6) | 216 | 20.4 (15.0, 25.7) | 216 | 28.7 (22.7, 34.7) | 216 | |

| Total | 40.5 (37.1, 43.9) | 805 | 28.0 (24.9, 31.1) | 805 | 31.7 (28.5, 34.9) | 805 | |

Question 11: Has the person surveyed ever had wheezing or whistling in the chest at any time in the past?; Question 12: Has the person surveyed had wheezing or whistling in the chest in the last 12 months?; Question 16: Has the person surveyed ever had asthma?; n: total number surveyed who answered the respective questions. Percentages and 95% confidence intervals are shown.

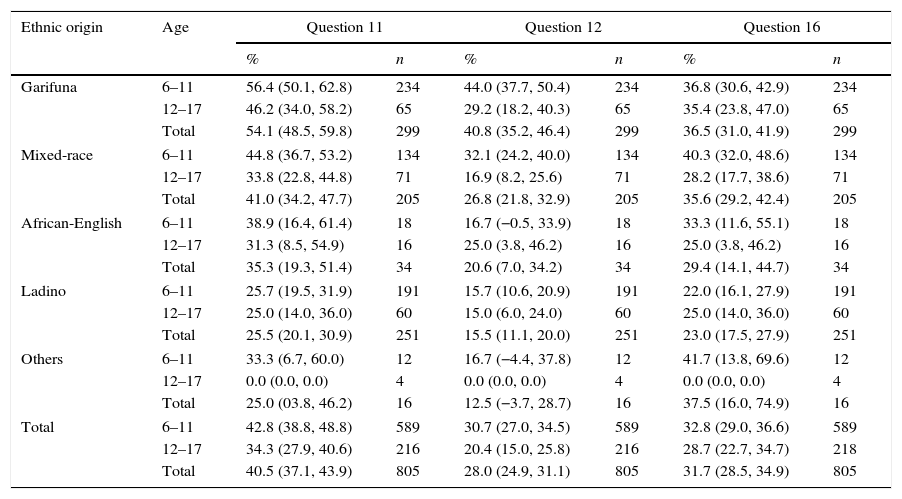

Given the ethnic diversity, the prevalence in each ethnic group (both parents with the same ethnicity) was determined. Table 2 shows the prevalence values by ethnic group separated into two age groups and the totals. Taking both age groups together, the higher lifelong cumulative prevalence value for wheezing (measured by question 11) was found in the Garifuna with 54.1% and the lowest in “others” with 25.0%. The point prevalence of wheezing (in the last 12 months) was highest in the Garifuna with 40.8% and lowest in “others” with 12.5%, while the highest cumulative prevalence of having or having had asthma was also found in the Garifuna with 36.5% and the lowest in “others” with 16.6%. No significant differences were observed in the prevalence between the Garifuna, mixed-race, and African-English ethnic groups; however significant differences were observed between the Garifuna and Ladinos (p=0.0004, X2; 0.0005, FET), and between mixed-race and Ladinos (p=0.0021, X2;=0.0025, FET); and in general, there was a higher prevalence in those with African descent in comparison with the Ladinos (p=0.0006, X2; 0.0007, FET).

Prevalence of asthma by ethnic group.

| Ethnic origin | Age | Question 11 | Question 12 | Question 16 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | % | n | ||

| Garifuna | 6–11 | 56.4 (50.1, 62.8) | 234 | 44.0 (37.7, 50.4) | 234 | 36.8 (30.6, 42.9) | 234 |

| 12–17 | 46.2 (34.0, 58.2) | 65 | 29.2 (18.2, 40.3) | 65 | 35.4 (23.8, 47.0) | 65 | |

| Total | 54.1 (48.5, 59.8) | 299 | 40.8 (35.2, 46.4) | 299 | 36.5 (31.0, 41.9) | 299 | |

| Mixed-race | 6–11 | 44.8 (36.7, 53.2) | 134 | 32.1 (24.2, 40.0) | 134 | 40.3 (32.0, 48.6) | 134 |

| 12–17 | 33.8 (22.8, 44.8) | 71 | 16.9 (8.2, 25.6) | 71 | 28.2 (17.7, 38.6) | 71 | |

| Total | 41.0 (34.2, 47.7) | 205 | 26.8 (21.8, 32.9) | 205 | 35.6 (29.2, 42.4) | 205 | |

| African-English | 6–11 | 38.9 (16.4, 61.4) | 18 | 16.7 (−0.5, 33.9) | 18 | 33.3 (11.6, 55.1) | 18 |

| 12–17 | 31.3 (8.5, 54.9) | 16 | 25.0 (3.8, 46.2) | 16 | 25.0 (3.8, 46.2) | 16 | |

| Total | 35.3 (19.3, 51.4) | 34 | 20.6 (7.0, 34.2) | 34 | 29.4 (14.1, 44.7) | 34 | |

| Ladino | 6–11 | 25.7 (19.5, 31.9) | 191 | 15.7 (10.6, 20.9) | 191 | 22.0 (16.1, 27.9) | 191 |

| 12–17 | 25.0 (14.0, 36.0) | 60 | 15.0 (6.0, 24.0) | 60 | 25.0 (14.0, 36.0) | 60 | |

| Total | 25.5 (20.1, 30.9) | 251 | 15.5 (11.1, 20.0) | 251 | 23.0 (17.5, 27.9) | 251 | |

| Others | 6–11 | 33.3 (6.7, 60.0) | 12 | 16.7 (−4.4, 37.8) | 12 | 41.7 (13.8, 69.6) | 12 |

| 12–17 | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 4 | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 4 | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 4 | |

| Total | 25.0 (03.8, 46.2) | 16 | 12.5 (−3.7, 28.7) | 16 | 37.5 (16.0, 74.9) | 16 | |

| Total | 6–11 | 42.8 (38.8, 48.8) | 589 | 30.7 (27.0, 34.5) | 589 | 32.8 (29.0, 36.6) | 589 |

| 12–17 | 34.3 (27.9, 40.6) | 216 | 20.4 (15.0, 25.8) | 216 | 28.7 (22.7, 34.7) | 218 | |

| Total | 40.5 (37.1, 43.9) | 805 | 28.0 (24.9, 31.1) | 805 | 31.7 (28.5, 34.9) | 805 | |

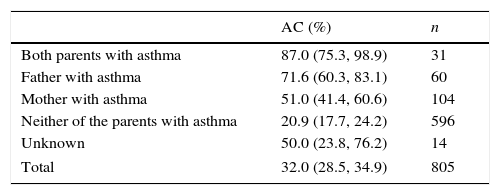

Table 3 shows the proportion of children with asthma when neither of the parents had asthma; and when only the mother, only the father, or both had it. A higher proportion of asthmatic children was found when both parents were asthmatic (87%) in comparison with when neither of the parents were (20.9%) (p=0.0001, X2; 0.0001, FET). The proportion of asthmatic children was similar when comparing when only the father was asthmatic with when both parents were (p>0.05, X2 and FET). A high proportion of asthmatic children was obtained when only the father was asthmatic than when only the mother was (p=0.0095, X2; 0.0133, FET). The predominance effect on the probability of an asthmatic child when only the father is asthmatic is mainly seen in the communities where the Garifuna ethnic group predominates. Similarly, in the cases where only the father was asthmatic, as in those where only the mother was asthmatic, a higher proportion of asthmatic children were seen versus when neither of the parents had had asthma (p<0.05, X2 and FET).

Correlation of parents and children with or without asthma.

| AC (%) | n | |

|---|---|---|

| Both parents with asthma | 87.0 (75.3, 98.9) | 31 |

| Father with asthma | 71.6 (60.3, 83.1) | 60 |

| Mother with asthma | 51.0 (41.4, 60.6) | 104 |

| Neither of the parents with asthma | 20.9 (17.7, 24.2) | 596 |

| Unknown | 50.0 (23.8, 76.2) | 14 |

| Total | 32.0 (28.5, 34.9) | 805 |

AC: asthmatic child; n: total number surveyed.

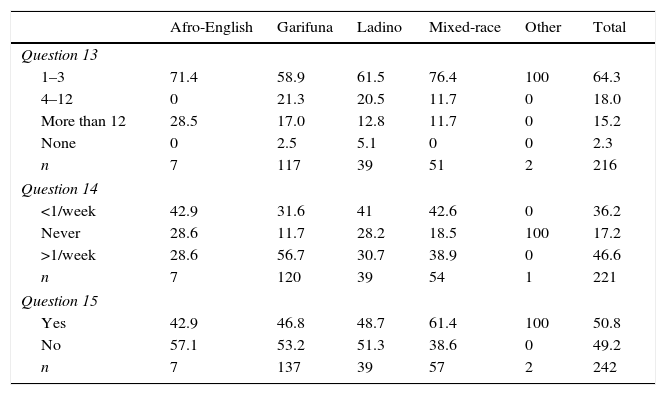

We studied the severity of the symptoms based on three questions: the number of wheezing episodes in the last 12 months, interruption of sleep due to wheezing, and difficulty speaking during an attack (Table 4). The highest asthma attack values were seen in the African-English, with more than 12 episodes in 28.5%. In contrast, mixed-race subjects had the fewest attacks, with 1–3 episodes in the last 12 months in 76.4% of the cases. The majority of the Garifuna reported having awoken more than one night per week due to wheezing, with a proportion of 56.7%, while in the rest of the groups the presences of night-time symptoms were mostly less than once per week. Regarding difficulty speaking during an attack, it was found that in most of the mixed-race subjects (61.4%) wheezing had been so strong that it prevented them from saying two words in a row without having to stop to breath. In the other groups, most of the responses were negative.

Severity of symptoms.

| Afro-English | Garifuna | Ladino | Mixed-race | Other | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question 13 | ||||||

| 1–3 | 71.4 | 58.9 | 61.5 | 76.4 | 100 | 64.3 |

| 4–12 | 0 | 21.3 | 20.5 | 11.7 | 0 | 18.0 |

| More than 12 | 28.5 | 17.0 | 12.8 | 11.7 | 0 | 15.2 |

| None | 0 | 2.5 | 5.1 | 0 | 0 | 2.3 |

| n | 7 | 117 | 39 | 51 | 2 | 216 |

| Question 14 | ||||||

| <1/week | 42.9 | 31.6 | 41 | 42.6 | 0 | 36.2 |

| Never | 28.6 | 11.7 | 28.2 | 18.5 | 100 | 17.2 |

| >1/week | 28.6 | 56.7 | 30.7 | 38.9 | 0 | 46.6 |

| n | 7 | 120 | 39 | 54 | 1 | 221 |

| Question 15 | ||||||

| Yes | 42.9 | 46.8 | 48.7 | 61.4 | 100 | 50.8 |

| No | 57.1 | 53.2 | 51.3 | 38.6 | 0 | 49.2 |

| n | 7 | 137 | 39 | 57 | 2 | 242 |

All the values are expressed as percentages except for n. Question 13: How many attacks of wheezing has the person surveyed had in the last 12 months?; Question 14: In the last 12 months, how often, on average, has the sleep of the person surveyed been disturbed due to wheezing?; Question 15: In the last 12 months has wheezing ever been severe enough to limit the speech of the person surveyed to only one word at a time between breaths?; n: total number surveyed who answered the corresponding question.

This study reveals an unusually high prevalence of asthma in the participants from the studied communities, especially the Garifuna, and the continental subjects among them. We were especially surprised by the high prevalence found in the communities of Bajamar, followed by Travesía. One possibility is the existence of a sample bias since in these two communities the survey was conducted house-by-house with the help of community healthcare personnel in contrast to completing the survey in the schools in the rest. However, the community of Punta Gorda, also Garifuna, presented a high prevalence, the highest of the communities on Roatán Island. Another factor to consider is the possible ubiquity of intestinal parasites in the Garifuna communities that may lead to the onset of Loeffler's syndrome.16–18

There are a large number of studies supporting the idea that ascariasis modifies that pathogenesis of asthma and other allergic diseases. Based on several factors related to the type of parasites, the host, exposure time, intensity of the infestation, and the environment, roundworms can either cause immunosuppression or increase Th2 responses.19 Lastly, a third source of error could be having cultural roots that cause variation in the percentage of specificity of the questions from one population to another.7,20

The fact of finding differences in the prevalences not only between ethnic groups, which reflects the influence of genetic composition, but also between communities inhabited by the same ethnic groups is interesting as it emphasises the effect of environmental and socioeconomic factors. Thus, in the communities of Bajamar, Travesía, and Punta Gorda, all of Garifuna descent, there may be a strong hereditary factor influencing the prevalence of asthma. Conversely, it is likely that in Coxen Hole environmental factors take precedence. The results agree with different studies conducted in Latin American where significant differences were observed in the prevalence of asthma in different regions, and the data suggest that the striking variability observed between the sites cannot be explained by methodological, linguistic, geographic, racial, or educational differences alone.21

In several studies a large correlation between asthma and belonging to an ethnic minority, especially African ancestry, has been observed.22–24 Our study reveals a higher prevalence in the Garifuna and Afro-English, both ethnic groups of African descent, versus the Ladinos. These results agree with similar findings in Trinidad and Tobago, where the symptoms were most common in the population of African and mixed descent than in the population with Asian roots.25 Similarly, it was observed in Colombia that asthma and high IgE levels are significantly associated with African heritage and a low socioeconomic level.26

It is possible that some presumed cases of asthma are due to the presence of concomitant diseases such as sickle-cell anaemia, a hereditary disorder common in persons with African heritage which is correlated with a higher probability of having asthma.27 It is unknown if airway hyperreactivity appears in sickle-cell anaemia as a distinct, separate, and independent entity from asthma, but it is known that the presence of asthma is a negative prognostic factor since it increases the frequency of acute chest syndrome and the progression of sickle cell chronic lung disease.27,28 Asthma can generally be determined using a questionnaire in the general population, but it is not clear if it is reliable in the population with sickle-cell anaemia.28

According to GINA, being male is a risk factor for having childhood asthma. As children grow, the difference between the sexes becomes smaller with age, and in adults the prevalence is higher in women than in men.1 In our study, the prevalence of asthma between the genders varied between communities. On Roatán Island, the patients were mostly male; however, in the continental coastal communities, most of the cases corresponded to females. Several studies report that the prevalence of asthma is higher in males and the hypothesis to explain this predominance would be the smaller diameter and increased tone of the respiratory tract, with a smaller pulmonary flow during the first year of life, more evident in boys than in girls, a trend which is reversed in adolescence.29–32 In this work, no significant difference in the prevalence of asthma was demonstrated between the two sexes.

Poor psychological well-being and a family history of asthma have been associated with a higher risk of asthma regardless of the ethnic group.33 Moreover, an up to four-fold increase in the risk of having asthma has been observed if there is a family history.32 We observed a higher prevalence in children when both parents were asthmatic, and when only the father is asthmatic, in comparison to when only the mother is, or when neither of the parents had asthma. In Guáimaro, Cuba, it was observed that with more asthmatic relatives, there was an earlier disease onset, and a greater number of attacks and hospital admissions. When the father has a history of the disease, asthma had an earlier onset, but when both parents had the disease, the mean number of attacks and hospital admissions, as well as the severity, were greater.34 Conversely, in Boston, Massachusetts, it was found that the probability of having a child with asthma was three times higher when one of the parents in the family had a history of asthma, and six times higher when both parents had that history. The study reported that the probability of a child having asthma was greater when the mother had a history of it, differing from our results.35 Thus, the hereditary factor is widely demonstrated, since the fact that the children with allergic and/or asthmatic parents have a higher risk of asthma speaks eloquently in favour of a strong genetic component, but the dissimilar results are evidence of a larger heterogeneity and the participation of environmental factors in the condition.

To date, there have been multiple research projects and updates on the genes associated with developing asthma through genomic-wide association studies (GWAS), and more than 100 susceptibility genes have been found.36,37 Regardless, wide-scale genomic studies continue. The Garifuna ethnic group has special characteristics that make it substantially different from the rest of the groups with African heritage in the Americas, including a tri-ethnic mix, two population bottlenecks, and a rapid population expansion along the Honduras coasts in the last two centuries. This makes it ideal for genomic studies to find new susceptibility genes.38,39

By identifying the mentioned risk groups, and since the genetic and hereditary factors are not modifiable, to prevent the incidence and prevalence of the disease, early medical assessment is recommended in that population to diagnose it early and treat it appropriately. Additionally, prioritising activities and programs focused on decreasing the risk factors that are modifiable in these communities would help to decrease the morbimortality and the incidence of this disease.

We should mention that there are currently few studies in Honduras on the prevalence of asthma and no studies have been conducted on the ethnic groups and their correlation with family histories of the disease, therefore this research study is a tool that will contribute to future studies. It will also contribute knowledge about the disease-population relationship and its implications in the development and lifestyle of the ethnic groups in the coastal region of our country.

LimitationsTo classify the severity of asthma in children and adolescents, in addition to the symptoms already described, it is necessary to assess the need for a quick relief bronchodilator and to determine the respiratory function assessment values. In this work, these two parameters were not taken into account due to logistic limitations.

It is important to mention that the dialect of the different ethnic groups (creole English, Miskito, and Garifuna) may have been a source of bias for spoken and written comprehension of certain parameters of the survey given. Pulmonary function tests are suggested to give continuity to this study.

Ethical disclosureProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Source of fundingThe work was funded by the authors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.