Hypothenar hammer syndrome is an uncommon injury of the ulnar artery in its passage through Guyon's canal, and has been associated with repetitive trauma. Its diagnosis requires a high level of suspicion and a careful clinical interview. The appropriate treatment is not well defined in the literature, ranging widely from medical treatment to reconstructive surgery. A clinical case is presented of a 52-year-old healthy male, who presented with numbness of his fourth and fifth fingers after a trauma at the hypothenar eminence. The Allen test highlighted an absence of vascularisation from the ulnar artery, thus suspecting an ulnar artery thrombosis, which was later confirmed by angio-MRI. The thrombosed segment was resected and a by-pass with a forearm vein was performed to reconstruct the distal arterial flow, presenting with a good functional outcome at 6 months follow-up.

El síndrome del martillo hipotenar es una infrecuente lesión de la arteria cubital a su paso por el canal de Guyon relacionada con los traumatismos repetitivos. Su diagnóstico requiere un elevado índice de sospecha y una adecuada historia clínica. Su tratamiento no está bien definido en la literatura, y va desde tratamiento médico hasta cirugía reconstructiva. Presentamos el caso de un varón de 52 años con parestesias de los dedos cuarto y quinto tras un traumatismo en la eminencia hipotenar. En el test de Allen destacó la ausencia de vascularización por parte de la arteria cubital, por lo que se sospechó una trombosis de la arteria que se confirmó mediante angiorresonancia. Se realizó resección del fragmento trombosado y bypass con una vena antebraquial para reconstruir el flujo distal. Presentó una evolución satisfactoria a los 6 meses de seguimiento.

The first description of post-traumatic thrombosis of the ulnar artery at distal level from a blunt trauma was published by von Rosen in 1934, but it was not until 1970 that Conn et al. gave a name to this infrequent lesion as hypothenar hammer syndrome (HHS) because it usually presents in people who use the palm of their hand as a substitute for a hammer, repeatedly beating or contusing the ulnar artery against the uncinate process of the unciform bone.1

This highly infrequent lesion2 which is characterised by pain, cold, changes in colouring, digital ischaemia trophic lesions, paresthesias in the ulnar nerve area and, on occasion, a palpable mass at hypthenar eminence.1

Its diagnosis is essentially clinical and therefore requires of a high level of suspicion, although Doppler ultrasound, angio MRI and arteriogram are useful. Its treatment depends on the intensity and speed of the appearance of symptoms and may vary from an oral medical treatment to a microsurgical reconstruction of the damaged segment.2

We present the clinical case of acute HHS from thrombosis of the ulnar artery treated by resection of the damaged segment and reconstruction using a bypass with the autologous vein.

Clinical caseA male aged 52, right-handed, with no significant medical history and who worked in a car factory. He went to the emergency department, presenting with numbness in his fourth and fifth fingers of the right hand after trauma in his job, in which he impacted with the heel of his hand three days prior to consultation. He had not had any previous traumas or changes in sensitivity.

Clinical examination revealed that he presented with a 2cm superficial contuse wound at hypothenar eminence. There was no deformity in fingers, hand or wrist. Passive and active movement was complete. Mild pain on probing of the hypothenar eminence. Paresthesias at fifth finger level and ulnar edge of fourth finger. Absence of any signs of compression of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel. Absence of any Tinel's sign in the epitrochlear-olecranon tunnel. Separation of the fingers against resistance (dorsal interossei muscles) not limited. No Froment's sign. In the Allen test at wrist level there was no vascularisation of the ulnar artery (which was, however, present on examination of the left wrist).

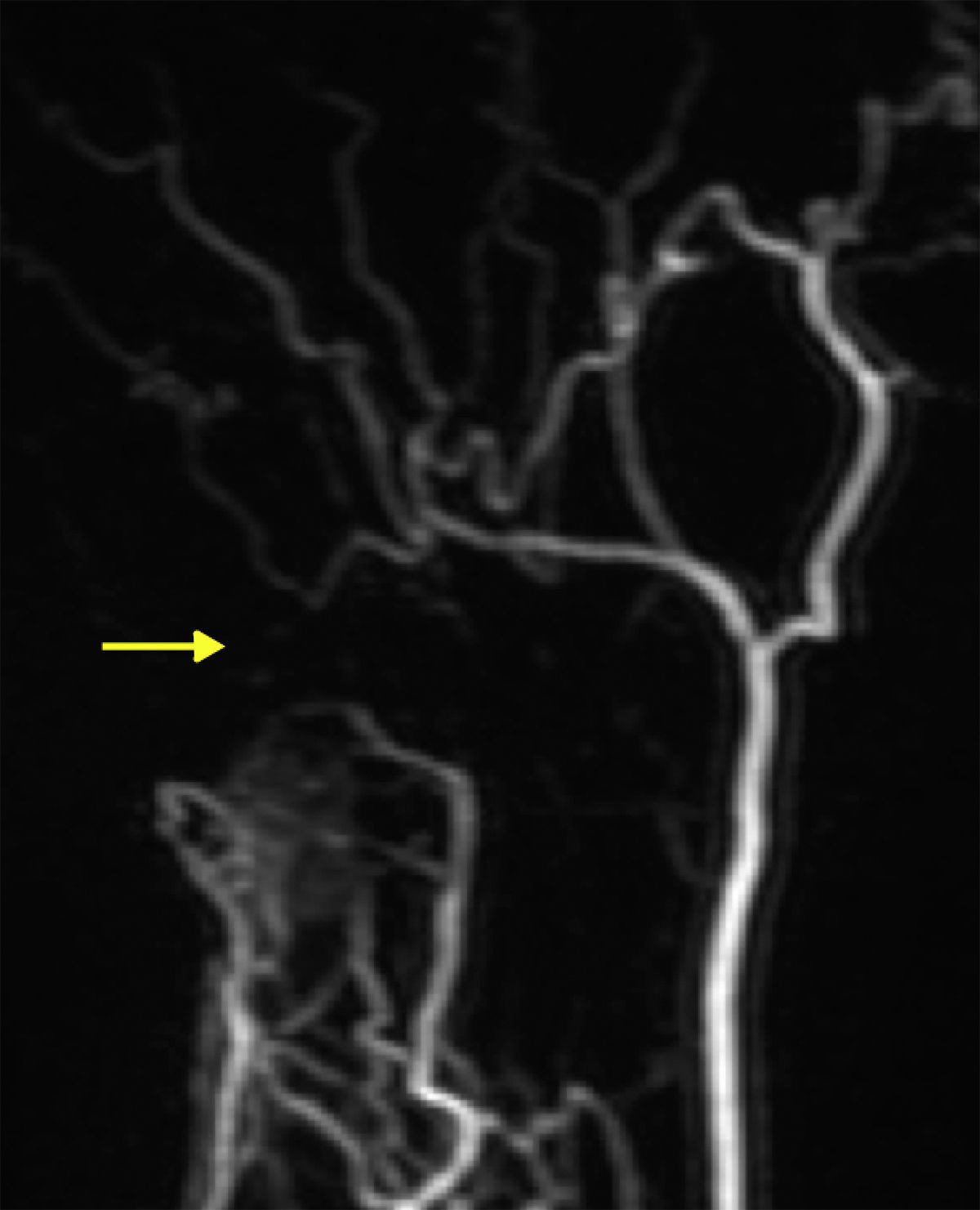

A Doppler ultrasound was requested on suspicion of ulnar artery thrombosis and this showed atheromatose calcifications of the ulnar artery at Guyon canal level with narrowing of over 50% of arterial lumen which led to a reduction in distal blood flow. An angio-MRI confirmed the diagnosis (Fig. 1).

The patient was assessed 7 days later: parethesias continued in the fourth and fifth fingers of the right hand and the pathological situation of the Allen test was maintained. A grip test was performed with the Jamar® dynamometer, Patterson Medical, Warrenville, IL, U.S.A. and the patient had grip strength of 33kg in the right hand and 58kg in the left hand. As a result, the patient was referred for surgical treatment.

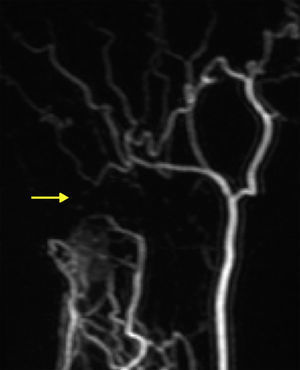

The intervention was performed in the outpatient department, under locoregional (axillary plexus) anaesthesia, with the patient in a supine position and with the arm on a surgical hand table. A preventative effects tourniquet was used at the beginning of the surgical intervention and optical magnification was used. Distal and palmar forearm approach to the ulnar artery was used, the artery was identified proximally to the healthy area and the carpal tunnel and Guyon canal were opened. We identified numerous atheroma plaques, the artery being porous up to the branching out between the deep ulnar artery, which accompanies the main branch of the ulnar nerve and the branch for the superficial palmar vascular arc, where a thrombosed area extending proximally of 2cm (Fig. 2) was detected. Embolectomy was attempted using a Fogarty catheter proximally and distally but this was unsatisfactory and we therefore resected the thrombosed segment. The ischaemic tourniquet was removed and a forearm vein bridge was used, which was conversely positioned, to reconstruct the distal artery blood flow. Skin closure was performed and it was confirmed that local temperature of the fourth and fifth fingers was appropriate. The hand was immobilised with a thermoplastic cast for 2 weeks until the skin suture was removed.

ResultParesthesias of the fourth and fifth fingers immediately disappeared after surgery. During the post-operative period the patient presented with surgical wound maceration which was resolved using local cures. The patient was asymptomatic six months after surgery, had returned to work and had a grip strength (grip test measured with the Jamar® dynometer, Patterson Medical, Warrenville, IL, U.S.A.) of 43kg in the right hand and 51kg in the left hand.

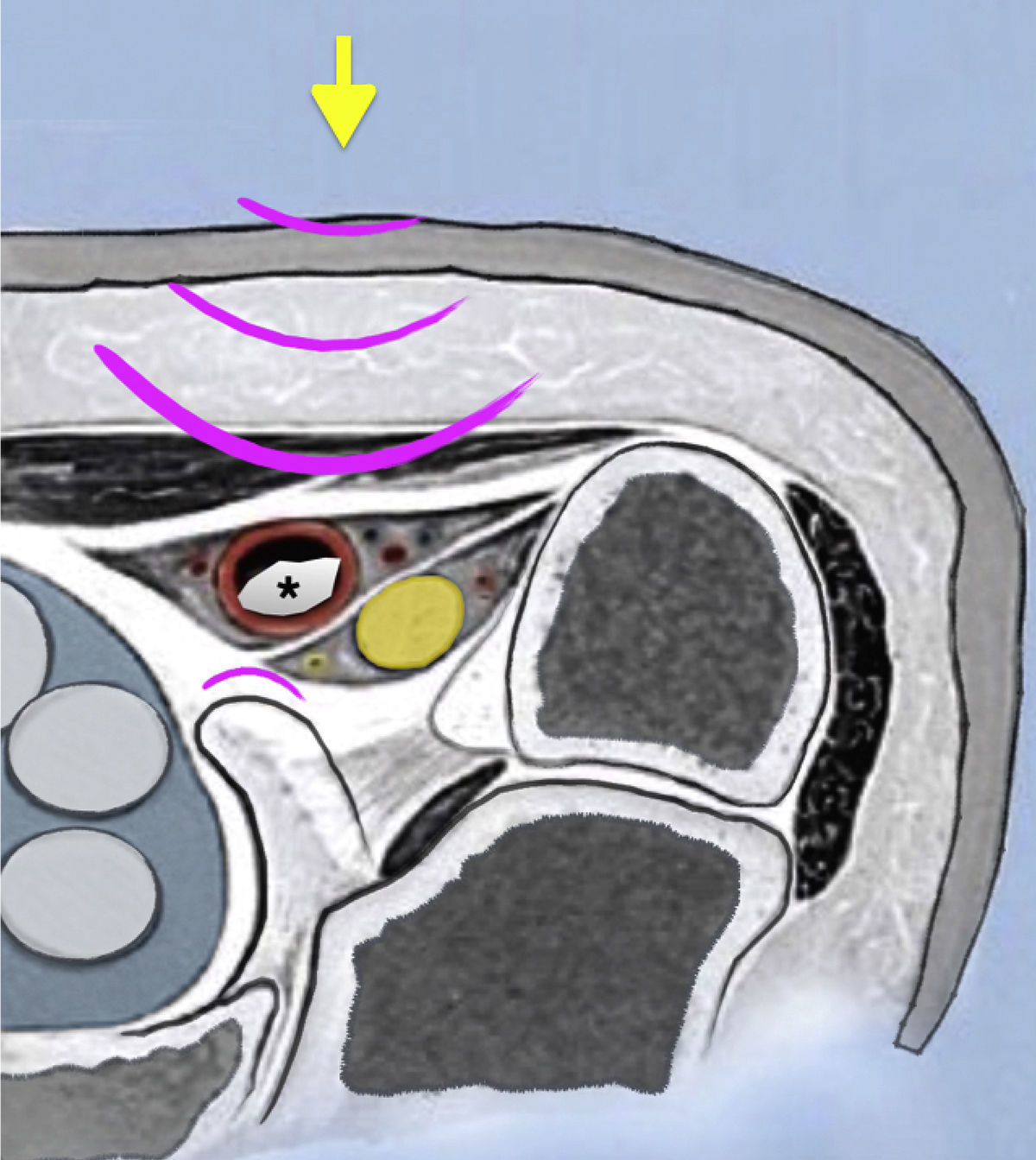

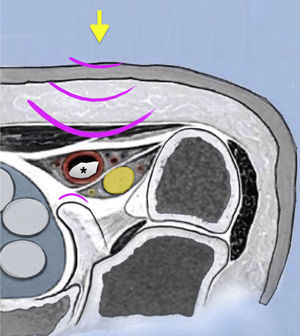

DiscussionThe vulnerability of the ulnar artery in the Guyon canal is due to the fact that at this level, the artery and the ulnar nerve are only covered by a thin layer of fibres from the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon, the palmaris brevis muscle, subcutaneous fat and skin. During trauma, the artery is trapped between the dorsal unciform and external volar pressure1,2 (Fig. 3) with a possible lesion of the inner vascular layer that triggers platelet aggregation and posterior arterial segmentary thrombosis (60% of cases according to Marie et al.3). We may also find aneurysmal swelling of the artery when the lesion reaches the mid layer (40%), which is associated with distal digital embolism in up to 45% of cases.2–4

HHS is an infrequent cause of digital ischaemia which represents under 2% of over 1300 cases who present at a vascular surgical centre with symptoms relating to the hand.2 Many patients with an ulnar artery occlusion which has become chronic are also asymptomatic and do not consult a physician. The real incidence rate is therefore not well defined.5

Precise aetiology remains unknown, although it is thought that a genetic predisposition exists,4 with trauma as the initial cause.

It typically affects the dominant hand in the fifth decade of life in a man during work or recreational activities where the heel of the hand is repeatedly used as a hammer. It therefore usually appears insidiously although may rarely appear after a single trauma, as occurred in this clinical case.1,4,6 It has also been described in sports people and in connection with the applause of fans who are perhaps over enthusiastic.6

The clinical signs of HHS depend on the extension of the arterial occlusion, the speed of its appearance and whether collateral circulation may occur or not.

Patients frequently consult over pain, intolerance to cold or changes in colouring. Paresthesias, numbness or weakness appear after the occlusion of the ulnar artery within the limits of the Guyon canal6 as represented by our case. The most notable signs are the presence of a mass in the cases of aneurysmal swelling, which may be throbbing (in under 10%)6 or not, lowering of sensitivity, reduction in speed of capillary refill in the nail bed, alternation of the ulnar flow in the Allen test at wrist level and in more severe cases, digital ulcers may appear and even gangrene which may lead to digital amputation. Fortunately the latter is infrequent.2,6

Clinical diagnosis requires a high degree of suspicion. Correct anamnesis and detailed physical examination are essential and must include the Allen test. This is a fast, simple, greatly useful test which can guide us towards the diagnosis of vascular impairment.

Several treatments have been described for this syndrome. Conservative treatment (stop smoking, medical treatment with vasodilators and thrombolytics) is usually stated in the literature as being initial treatment.2,6 Medical or surgical sympathectomy also has its indications and, finally, surgical treatment with resection of the wounded segment or its reconstruction. There is no easy choice between one or another treatment nor how much time to wait before initiating medical treatment and the literature is not of great help since published series are scarce and scientific quality is not high due to the non existence of random prospective studies which compare one or the other option.

We believe that treatment choice should depend on the speed of appearance of clinical symptoms. A progressive arterial occlusion will lead to the development of collateral circulation, with the patient asymptomatic or with low intensity symptoms which we may treat conservatively, at least initially but, on the other hand, an acute thrombosis allows for no vascular adaptation, and my lead to digital ischaemia and a local inflammatory response that could compress the ulnar nerve in the Guyon canal. In these cases, we consider a surgical treatment approach to be of choice to reconstruct the arterial flow whenever possible.

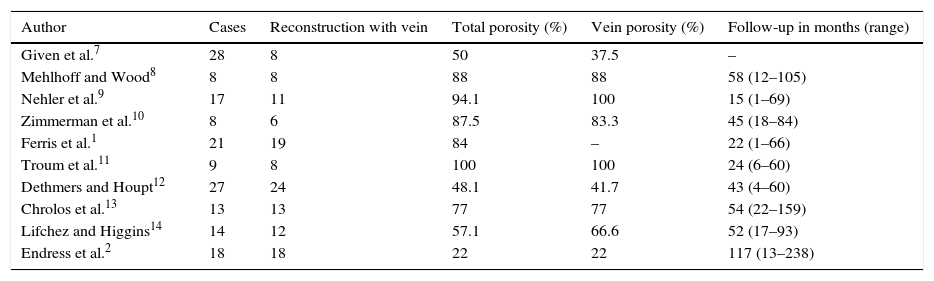

The porosity of the graft long term when the bypass with a vein is used is not satisfactory, although few studies have been conducted with a prolonged follow-up (Table 1). These results improve when the graft is arterial2,15,16 although the occlusion rate is not related to the clinical result, since patients are satisfied and present minimal functional repercussion.2

Most relevant series published in the literature.

| Author | Cases | Reconstruction with vein | Total porosity (%) | Vein porosity (%) | Follow-up in months (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Given et al.7 | 28 | 8 | 50 | 37.5 | – |

| Mehlhoff and Wood8 | 8 | 8 | 88 | 88 | 58 (12–105) |

| Nehler et al.9 | 17 | 11 | 94.1 | 100 | 15 (1–69) |

| Zimmerman et al.10 | 8 | 6 | 87.5 | 83.3 | 45 (18–84) |

| Ferris et al.1 | 21 | 19 | 84 | – | 22 (1–66) |

| Troum et al.11 | 9 | 8 | 100 | 100 | 24 (6–60) |

| Dethmers and Houpt12 | 27 | 24 | 48.1 | 41.7 | 43 (4–60) |

| Chrolos et al.13 | 13 | 13 | 77 | 77 | 54 (22–159) |

| Lifchez and Higgins14 | 14 | 12 | 57.1 | 66.6 | 52 (17–93) |

| Endress et al.2 | 18 | 18 | 22 | 22 | 117 (13–238) |

HHS is a lesion of very low incidence where a detailed anamnesis, high degree of clinical suspicion and appropriate clinical examination (that must include the Allen test) are essential to diagnosis. Treatment will depend on speed of lesion appearance, so that when this is acute, we believe the ideal treatment is the reconstruction of the arterial flow. Although our graft may thrombose in the long term, sufficient time is gained to develop an appropriate collateral circulation leading to a good clinical outcome.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence V.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of humans and animal subjectsThe authors declare no experiments have been performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare they have adhered to the protocol of their centre of work on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Jiménez I, Manguila F, Dury M. Síndrome del martillo hipotenar. A propósito de un caso. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2017;61:354–358.