The indiscriminate practice of radiographs for foot and ankle injuries is not justified, and numerous studies have corroborated the usefulness of clinical screening tests such as the Ottawa Ankle Rules. The aim of our study is to clinically validate the so-called Shetty test in our area.

Material and methodA cross-sectional observational study by applying the Shetty test to patients seen in the emergency department.

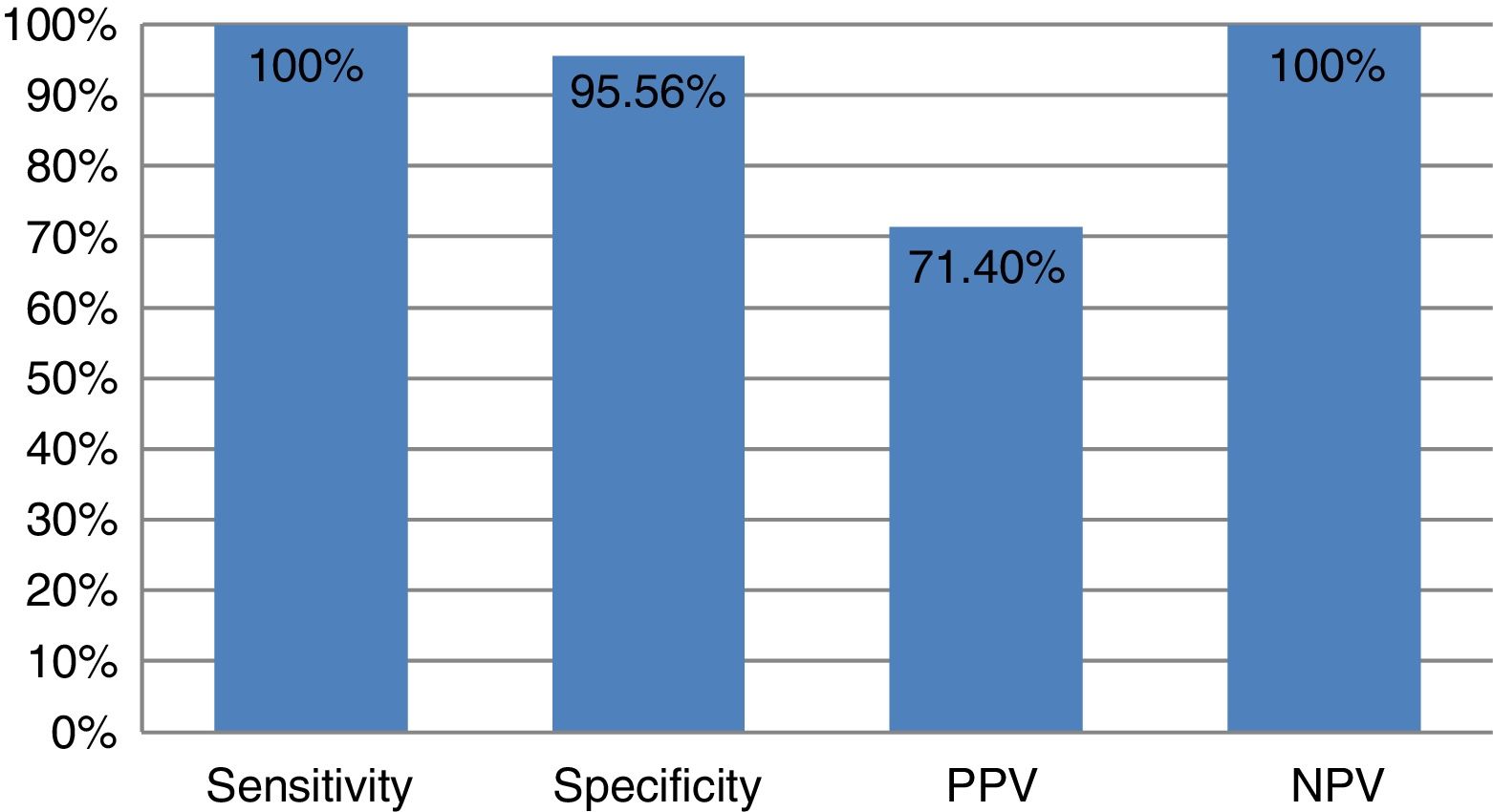

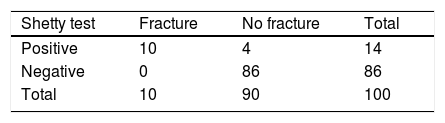

ResultsWe enrolled 100 patients with an average age of 39.25 years (16–86 years). The Shetty test was positive on 14 occasions. Subsequent radiography revealed a fracture in 10 cases: four were false-positives. The test was negative in the remaining 86 patients and radiography confirmed the absence of fracture (with sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 95.56%, positive predictive value of 71.40%, and negative predictive value of 100%).

ConclusionsThe Shetty test is a valid clinical screening tool to decide whether simple radiography is indicated for foot and ankle injuries. It is a simple, quick and reproducible test.

La práctica indiscriminada de radiografías en los traumatismos de pie y tobillo no está justificada y numerosos estudios han corroborado la utilidad de los tests de despistaje clínicos como las reglas del tobillo de Ottawa. El objetivo de nuestro estudio es validar clínicamente el denominado test de Shetty.

Material y métodoEstudio transversal observacional mediante aplicación del test de Shetty a pacientes atendidos en el Servicio de Urgencias.

ResultadosSeleccionamos a 100 pacientes con una edad media de 39,25 años (16–86). Tras efectuar el test de Shetty, la prueba fue positiva en 14 ocasiones. Realizando la radiografía posterior, se constató que en 10 casos había fractura y que 4 eran falsos positivos. Por otro lado, en los 86 pacientes restantes el test fue negativo y la radiografía confirmó la ausencia de fractura (sensibilidad del 100% y una especificidad del 95,56%, así como un valour predictivo positivo del 71,40% y un valour predictivo negativo del 100%).

ConclusionesEl test de Shetty es una herramienta de despistaje clínico válida a la hora de tomar decisiones sobre la indicación de la radiografía simple en lesiones del pie y tobillo. Además, es una prueba sencilla, rápida y reproducible.

Injuries secondary to direct or indirect trauma to the foot or ankle are very common in emergency departments in our environment, as both inpatients and outpatients, and in primary-care consultations.1–3 They represent almost 15% of total emergencies and up to 60% of trauma emergencies. Sprains to the external lateral ligament of the ankle is the most common acute trauma injury.3 Although in most cases these are banal injuries (ligamentous, capsular injuries or simple contusions) and clinically relevant fractures are only diagnosed in 13% of cases, it is a routine practice to perform indiscriminate radiography, most often without any objective criteria. This phenomenon is explained by various factors: long waiting times in the very overburdened emergency departments, at the request of the patient himself or herself, failing to comply with the established protocols or guidelines or noncompliance with those already in existence and, of course, so-called defensive medicine, for medical–legal reasons.4 These facts are just as clear in daily clinical practice where many hospitals perform simple X-rays before the appropriate physical examination.5

With this in mind, many studies have demonstrated that clinical screening tools can be used to drastically reduce the indication for radiography, with considerable saving of economical resources and time, as well as less ionising radiation to our patients. One such tool is the Ottawa Ankle Rules (OAR), designed by Canadian researchers led by Stiell in 1992,6 established as one of the most used for this purpose, and currently used in many emergency services worldwide.5–9 However, these rules require the collaboration of the patients, because they require them to walk with a probable foot or ankle fracture, and therefore they often cannot be carried out at the time of the acute trauma due to the pain experienced by the patient. In addition, we should not forget that the Rules imply a thorough examination, targeting certain anatomical points: all of which increases the physical examination times for each patient.

In this regard, Shetty et al.10 published a novel and simple test in 2013, seeking to simplify the OAR method: the authors themselves validated this application in fracture screening with a negative predictive value of 100%.

The aim of our paper is to demonstrate the application of the Shetty test as a clinical screening test for fractures of the foot or ankle in patients attended as emergencies in a tertiary level hospital.

MethodsAn observational, cross-sectional study of 100 patients attended in our hospital's emergency department between March 2016 and March 2017.

The criteria for inclusion in this study were:

- -

Direct or indirect trauma to the foot or ankle.

- -

Of less than 6h onset.

- -

Absence of previous assessment.

- -

Collaboration of the patient.

The following exclusion criteria were established that might falsify the results of our test and even make it difficult to perform:

- -

Previous foot or ankle fracture.

- -

Multiple trauma or multiple contusions.

- -

Concomitant fracture in lower limbs or pelvis that would affect performing the test.

- -

Sensitivity or mobility disorders.

- -

Mental disorders.

- -

Aged <16 years.

- -

Pregnant women.

- -

Having taken anti-inflammatories or analgesics before examination.

- -

Frank deformity of the foot or ankle.

- -

Simple X-ray performed before physical examination.

All the patients were assessed by two trained examiners (J.O.J. and P.M.V.). In all cases, the mechanism that caused the injury was recorded. Initially all the patients underwent the Shetty test and the clinical result was noted (Table 1). If negative for fracture, a targeted physical examination of painful points was undertaken to confirm the diagnosis according to our routine practice (contusion, sprain, etc.). Then the patients were prescribed analgesia and a plain X-ray was requested (anteroposterior and lateral of the ankle or anteroposterior and oblique of the foot), irrespective of the result of the test. This X-ray was then assessed by the co-author himself (M.H.P.). The result of the X-ray could be negative or positive, although in the case of fractures and as already described by Stiell,6 we considered a fracture to be clinically relevant and therefore a positive result, if it was displaced more than 3mm.

Based on the description by Shetty et al.,10 we undertook the test as he himself describes in his article (Fig. 1). The patient sits on a stretcher barefoot with his/her feet hanging down. Then we place a palm of a hand under the sole of their foot and ask them to press downwards as if attempting to stand. If at that time the patient experiences increased pain we consider the test positive, since this is a test that attempts to simulate load. It is a fast, simple and reproducible test that patients can perform easily even if they are in a great deal of pain.

Statistical analysisFor the statistical analysis, a database was created that included the patients using SPSS 11.0. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value were calculated. The confidence interval was set at 95%.

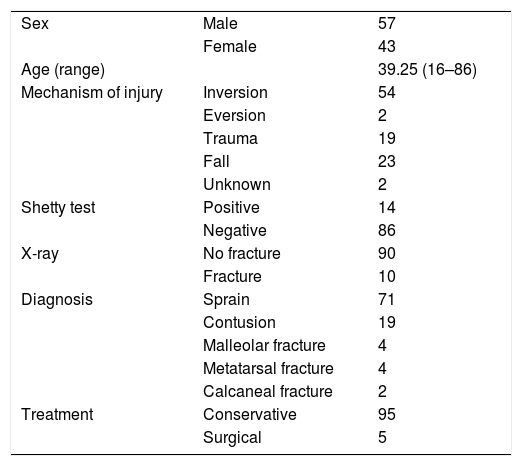

ResultsA total of 100 patients were selected from our centre between March 2016 and March 2017, aged between 16 and 86 years, with a mean age of 39.25 years (16–86 years). The distribution by sex was 57 males and 43 females. The most common mechanism of injury was forced inversion of the ankle (54%), followed by falls (23%), direct trauma (19%), eversion (2%) and unknown (2%).

Ankle sprain of greater or lesser severity was the most common final diagnosis (71%), followed by contusion (19%) and fracture (10%). Treatment was conservative in 95% of cases and surgical in the remaining 5% (four ankle fractures and one calcaneal fracture) (Table 2).

Epidemiology, diagnoses and treatment.

| Sex | Male | 57 |

| Female | 43 | |

| Age (range) | 39.25 (16–86) | |

| Mechanism of injury | Inversion | 54 |

| Eversion | 2 | |

| Trauma | 19 | |

| Fall | 23 | |

| Unknown | 2 | |

| Shetty test | Positive | 14 |

| Negative | 86 | |

| X-ray | No fracture | 90 |

| Fracture | 10 | |

| Diagnosis | Sprain | 71 |

| Contusion | 19 | |

| Malleolar fracture | 4 | |

| Metatarsal fracture | 4 | |

| Calcaneal fracture | 2 | |

| Treatment | Conservative | 95 |

| Surgical | 5 | |

The Shetty test was positive on 14 occasions after it was performed on the 100 patients in our series. When plain radiography was performed, a fracture was confirmed in 10 cases; therefore four of them were false-positives, after showing normal radiodiagnostic test results. Furthermore, the test was negative in the remaining 86 patients and X-ray confirmed the absence of fracture (Table 2).

The area under the curve ROC was 0.98 (95% CI: 0.926–0.997; p<0.001). The test achieved a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 95.56%, and a positive predictive value of 71.40% and negative predictive value of 100% (Fig. 2).

Three of the false-positives were female and aged 27, 42 and 46 years; the remaining case was a 22-year-old man. The diagnosis of three of the cases was sprain, while the 42-year-old woman was diagnosed with contusion: all of them were treated conservatively.

DiscussionInjuries to the foot and ankle are, without doubt, among the most common trauma injuries seen in clinical practice.1–3,11,12 Their conventional management in the emergency department involves thorough clinical examination targeting selective anatomical points for fracture screening. In this regard, the OAR,6 after they were published in 1992, constituted a valuable screening tool and became a part of most emergency departments over the world.

The first validity study of the OAR was performed by the authors themselves,13 who published a sensitivity of 100% in fracture diagnosis. Subsequently, in France, Auleley14 described a sensitivity of 99%. A United States meta-analysis published by Market et al.15 in 1998 achieved a sensitivity of 97% and a negative predictive value of 99%. The OAR have even achieved similar results in children,16 although the authors themselves advise more extensive studies for this group of the population.

Other papers, however, have achieved lower sensitivities,17–19 and even Tay et al.,20 with a sensitivity of 90%, consider them not applicable in their environment.

With a view to reducing the number of X-rays and consequent financial saving, Bachman et al.21 completed a systematic review of 27 studies that evaluated the implementation of the OAR, with a sensitivity close to 100%, and an average reduction in X-rays of 30–40%. In 2006,5 our group published a potential reduction of X-rays of around 80%, very much above that of other series, at around 30%, and also above that performed by Garcés et al.4 in our country.

For all the above reasons, the efficacy and feasibility of applying the OAR seem clear and proved in assessing foot and ankle injuries, to such an extent that recent studies recommend that it should be included as a task of the triage nurse in emergency departments.8 The recent article by Jonkheer et al.7 is of interest; they performed a systematic review to demonstrate whether the OAR remain valid more than 20 years since their publication. The results of their study find that they remain very reliable, although they state that other methods to avoid X-ray might also be useful and even complement the OAR, such as musculoskeletal ultrasound, which is currently very much in vogue.

Despite these published data of high reliability as initial fracture screening, the use of these rules in emergency departments over the world is not uniform. They are very highly used in English-speaking countries (Canada, the United Kingdom and Australia), but hardly used in the United States, France or Spain. The main criticisms against them are the loss of autonomy for the doctor in their physical examination and the reticence to use a rigid protocol in this examination. But, from our point of view, the main disadvantage of the OAR is that it is essential that the patient cooperates, they even have to take a few steps after the trauma, which is often impossible due to the pain they experience. Furthermore, the OAR require some experience in palpating certain anatomical points in looking for a fracture: the fifth metatarsal base, malleolus fibulae, etc., which require the examiner to have received prior training.

In this regard, from a practical point of view, based on our results and the results described by the Shetty group10 themselves, the Shetty test is faster, easy to perform even by inexperienced doctors, easy to record and, above all, less painful for the patient than the OAR. Its implementation in emergency departments could reduce waiting times, reduce costs (from 75 to 120 euros per X-ray is the current cost in our environment), avoid referrals to specialists and prevent ionising radiation to the patient (up to 0.6mSv per X-ray).

With regard to comparison with other diagnostic tests, our own group published the results of using the OAR in our environment in 2005.5 This study also included 100 patients with the same inclusion criteria and obtained 17% false-positives (in 17 patients the OAR were positive, but the X-ray was eventually negative), although we also managed to diagnose all the fractures (no false-negatives). Comparing both tests, although we acknowledge that these are not exactly the same group of patients, the ability to confirm that a patient does not have a fracture (negative predictive value) is maximal (100%). Therefore, both tests are very useful for fracture screening before an X-ray is indicated, but the Shetty test is clearly superior to the OAR in the percentage of false-positives (4 in our study and 17 in the previous study).

This study has a series of limitations which should be noted. Firstly, we highlight the interobserver variability in interpreting the Shetty test, although the two examiners were trained by one of the co-authors (M.H.P.) to perform the test in the same way. Secondly, the Shetty test is based on the presence or absence of pain on simulating load to the limb and it is well known that pain is a subjective symptom that varies widely among patients. Nevertheless, in our experience, patients tolerate the Shetty test well, and we can examine for the presence or absence of pain more easily.

In conclusion, the Shetty test in our environment has proved an easy, fast and reliable tool for screening for clinically relevant fractures in injuries to the foot or ankle, which has the potential to reduce the amount of X-rays performed in emergency departments.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We thank the family and community medicine residents who made it possible to perform this study during their orthopaedics and trauma shifts. We thank the Emergency Department of the University Hospital of the Canary Islands. We also thank the 6th year medical students, D. Sergio González Hernández and D. Luis A. Rojas Machin.

Please cite this article as: Ojeda-Jiménez J, Méndez-Ojeda MM, Martín-Vélez P, Tejero-García S, Pais-Brito JL, Herrera-Pérez M. Experiencia con la aplicación del test de Shetty para el despistaje inicial de fracturas del pie y tobillo en el área de Urgencias. Rev Espa Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2018;62:343–347.