The literature reports a set of variables associated with depression, anxiety and stress in health career students. The only one of these that could have a constant input is the structure of personality organisation. The present study aims to determine the relationship between the dimensions of personality organisation and depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms reported by first-year university health career students.

MethodsUnder a non-experimental ex-post-facto design, the personality organisation was evaluated in 235 1st year university, medical, nursing, and kinesiology from three universities of La Serena and Coquimbo (Chile). Inventory of personality organisation and scale of depression, anxiety and stress to sift participants was used. The relationship of personality with depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms was determined by multiple regression analysis.

ResultsIt was found that the primary and overall personality dimensions explained 28% of the variance of depression (p<0.01), 20% of anxiety, and stress 22%, with the use of primitive defenses and identity diffusion dimensions that largely contribute to the explanatory model.

ConclusionsThe dimensions of personality organisation could have a significant relationship with the emergence of depression, anxiety and stress, as the explanatory burden dimension provides the primitive defenses and identity diffusion. These results may be useful for early recognition of aspects of personality of applicants, and to perform actions that strengthen them in order to improve efficiency.

La literatura informa de un conjunto de variables asociadas a la depresión, la ansiedad y el estrés en estudiantes de salud. La única de ellas que tendría un influjo constante es la organización estructural de la personalidad. El presente trabajo ha determinado la relación de las dimensiones de organización de la personalidad con los síntomas depresivos, ansiosos y de estrés reportados por estudiantes universitarios de primer año de carreras de salud.

Material y métodoCon un diseño no experimental ex-post-facto, se evaluó la organización de personalidad de 235 universitarios de primer año de Medicina, Enfermería y Kinesiología de tres universidades de La Serena y Coquimbo (Chile). Se utilizó el inventario de organización de la personalidad y la escala de depresión, ansiedad y estrés para tamizar a los participantes. La relación de la personalidad con los síntomas depresivos, ansiosos y de estrés se determinó mediante análisis de regresión múltiple.

ResultadosSe encontró que las dimensiones primarias y generales de la personalidad explican un 28% de la varianza de la depresión (p<0,01), un 20% de la de ansiedad y un 22% de la de estrés, y el uso de defensas primitivas y difusión de identidad son las dimensiones que aportan mayormente al modelo explicativo.

ConclusionesLas dimensiones de la organización de la personalidad tendrían relación significativa en la emergencia de depresión, ansiedad y estrés; la dimensión defensas primitivas y difusión de identidad aporta la mayor carga explicativa. Estos resultados pueden ser útiles para reconocer tempranamente los aspectos de personalidad de los postulantes y realizar acciones que la fortalezcan para mejorar la eficacia adaptativa.

Studies on depression, anxiety and stress in healthcare science students have attracted more attention and acquired greater relevance in recent years.1–5 According to the literature, the emergence of such symptoms in this student group has a negative effect not only on their mental and physical well-being,5–7 but also on their social8 and academic environment.6 This results in poor academic achievements and can even influence their effectiveness as professionals in the future.4

Studies carried out in Chile8–10 have shown that the prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress in first-year healthcare science students and in their peers in the general population is higher than previously thought, which suggests a deterioration in the mental, social, academic and physical planes mentioned above.

A number of studies have explored the emergence of anxiety, stress and depression in these groups of university students, showing that these symptoms are related with a wide range of environmental variables such as infectious diseases12 and academic,5,6,14 sociodemographic and social6,13,14 and individual8,9,16–18 factors.

With regard to individual variables, although there are several that influence these symptoms, possibly one of the most relevant is personality,19,20 since personality organisation is the only variable that would, in theory, exert a continuous influence. This becomes more important when we consider that these students are in their late adolescence – one of the last stages of the process of identity consolidation21,22 – that will define largely unchangeable personal attributes that will provide different degrees of emotional stability and a sense of identity.23

According to Kernberg,24 dimensions of personality organisation explain the genetic and inborn disposition to intensity, rate and threshold of affect activation. These impact the individual, modulating their relationships with others and the way they conduct themselves and act in the world. When these dimensions describe inappropriate functioning, there is a greater tendency towards the appearance of intense negative effects, which generate emotional distress, a characteristic feature of borderline personality structures.23 Thus, it is established that personality dimensions, being attributes that exert a relatively permanent effect, have a more stable influence on different levels of emotional well-being,8 and become largely unchangeable. This is why it is important to understand their influence and real impact in terms of the emergence of these highly prevalent symptoms among healthcare science undergraduates.5,12

Given the above, insight into the effect of personality on depression, anxiety and stress in Chilean healthcare science students would allow healthcare professionals to focus their interventional and preventive efforts on early assessment of personality organisation. This would lead to the development of strategies aimed at identifying and effectively treating students who, due to their structural make-up, are at greater risk of suffering from these symptoms that undermine the mental health of university students15–17 and increase the risk of academic failure or delay.5,6,13

In this context, the main objective of this study is to determine the relationship between dimensions of personality organisation and symptoms of anxiety, depression and stress in first-year healthcare science undergraduates. This will in turn establish the magnitude of the influence of this structural disorder, and thus determine the degree to which the prevalence of these symptoms in the study group can be modified.

Materials and methodsThis is a non-experimental, ex-post-facto, cross-sectional study25,26 in a sample of 235 undergraduate healthcare science students (medicine, kinesiology and nursing) aged between 18 and 34 years (mean 20.7±3.41; median, 18) from three universities in the Coquimbo region of Chile.

Study subjects were selected from among a group of volunteers using non-probabilistic sampling methods.26 All the instruments used in this study were evaluated and approved by the ethics committee of the sponsoring university, and the study was then conducted in coordination with the departmental heads of the different universities involved. In each case (students from different universities), the objectives of the study were explained, and all voluntary participants were assured of the anonymity and confidentiality of the answers before giving their written informed consent to take part in the study.

The dimensions of personality organisation were evaluated using a version of the Inventory of Personality Organisation (IPO) adapted and validated for Chile.27,28 This self-report questionnaire consists of 83, 5-point Likert-type questions ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), organised into five scales: three primary (identity diffusion, primitive defence, reality testing) and two global (aggression and moral values). Of the primary scales, the expected scores are 33.82±8.59 in primitive defences, 44.96±13 in identity diffusion, and 31.95±9.72 in reality testing. Scores in the global scales, meanwhile, are 22.17±6.25 for moral values and 24.31±5.77 for aggression. In this study, the IPO scale achieved a Cronbach's alpha internal consistency score of 0.94. This shows an adequate factorial structure, and is consistent with other Chilean studies using the same instrument.8,27

The presence of symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress was evaluated using a version of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) adapted and validated for Chile.29 This instrument consists of 21, 5-point Likert-type questions ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all over the past week) to 5 (applied to me very much, or most of the time over the past week), organised into three scales: depression, anxiety and stress. Scores were interpreted as follows: ≥10 describes an average degree of depression, ≥8 is considered an average level of anxiety and ≥15 shows average levels of stress. The higher the score in each of the scales, the greater the severity of the symptoms. In the present study, the DASS-21 scale achieved a total consistency of α=0.90. This shows adequate factorial structure, and is consistent with other studies using this scale in the Chilean population.8,29

The results of both questionnaires were processed using the statistical program SPSS 15.30 Following the example of similar studies, we used measures of central tendency for descriptive variables, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test to determine sample distribution, the Pearson correlation coefficient for the correlation analysis, and multiple regression analysis for explanatory variables.8

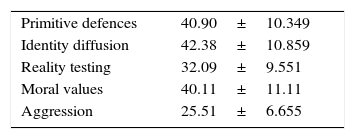

ResultsCharacterisation of personality and levels of depression, anxiety and stressWith regard to personality organisation, 28.93% of the students evaluated presented features of a “neurotic” organisation, while 66.38% presented a “high borderline” personality organisation, and only 4.69% presented a “low borderline” organisation. On average, scores for all dimensions were within Hoffman's normal range, with the exception of moral values28 (Table 1).

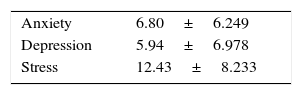

In total, 23%, 39% and 31% of participants presented medium to severe levels of depression, anxiety and stress, respectively. Mean scores for depression, anxiety and stress fell within the normal range, according to the parameters described by Lovibond and Lovibond31 (Table 2).

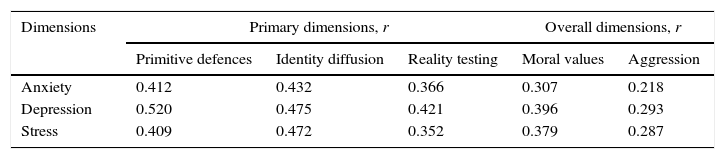

Relationship between personality organisation and levels of depression, anxiety and stressThe results of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test showed that the sample follows a normal distribution (p>0.05) in each of the dimensions that make up the variables. Regarding the correlation of the IPO and DASS-21 scales, all personality organisation dimensions were significantly correlated with anxiety, depression and stress (Table 3).

Correlation between personality dimensions and symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress.

| Dimensions | Primary dimensions, r | Overall dimensions, r | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primitive defences | Identity diffusion | Reality testing | Moral values | Aggression | |

| Anxiety | 0.412 | 0.432 | 0.366 | 0.307 | 0.218 |

| Depression | 0.520 | 0.475 | 0.421 | 0.396 | 0.293 |

| Stress | 0.409 | 0.472 | 0.352 | 0.379 | 0.287 |

Correlations are significant if <0.01.

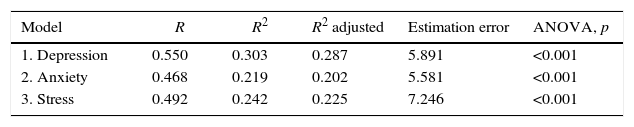

Finally, after verifying that the basic assumptions for linear regression analysis were met, a multiple linear regression analysis was performed to determine the relationship between personality organisation dimensions and depression, anxiety and stress. Predictive variables were: identity diffusion, use of primitive defences, reality testing, moral values and aggression, and dependent variables were depression, anxiety and stress. As shown in Table 4, personality dimensions produced significant changes in the r-squared value. This was also confirmed by the ANOVA of each item in the scale (p<0.01).

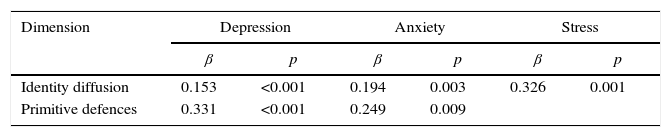

Within each scale, the variables “primitive defences” and “identity diffusion” obtained the highest beta coefficients in all three cases (Table 5).

DiscussionThe aim of this study is to determine the relationship between the dimensions of personality organisation and the development of symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress reported by first-year undergraduate healthcare science students. This is highly relevant, since personality is the only variable that, theoretically, exerts a permanent influence when compared with other variables reported in the literature as contributing to the emergence1,2,11,14 and higher prevalence3,5,10 of these symptoms in healthcare science students.

The results of this study confirm that a certain percentage of participants reported levels of depression, anxiety and stress ranging from moderate to severe. This is consistent with other studies carried out in Chile in healthcare science undergraduates,8,10–12 which report results similar to ours. However, this comparison should be interpreted with caution, given the diversity of measurement instruments used in these studies. Despite this, it is interesting to note that different methods of evaluating this phenomenon in Chilean healthcare science students show qualitatively similar results, suggesting the existence of a certain trend that merits investigation.8

As far as personality characterisation is concerned, it is interesting to note that a high percentage of study subjects are classified as high-level borderline personality organisation, a finding that contrasts with that of another study conducted in Colombia on university students.30,32 Although, according to the criteria proposed by Kernberg,22 this corresponds to pathological personality levels, it should be noted that the majority of the students included in the sample are 18 years of age, a time of transition from late adolescence to early adulthood,21 and a certain degree of identity instability characteristic of adolescence is to be expected in this population.22

The correlations found are consistent with those reported in another study done in Chile in the same population using the same variables,8 which strongly suggests the existence of a relationship between the symptoms studied and Kernberg's personality dimensions. Our findings confirm this hypothesis by showing a significant correlation between the dimensions of personality organisation and the presence of depression, anxiety and stress. This explains 28% of the depression variance, 20% of anxiety variance, and 22% of stress variance, mostly caused by primitive defences and identity diffusion.

This is a novel finding, since so far very few studies have evaluated the relationship between personality organisation and depression, anxiety and stress in university students. Our results support Kernberg's theory23,24 on personality, namely, that expressing identity diffusion with a preponderance of negative affect and an inconsistent sense of self and others is bound to cause emotional instability and conflicting interpersonal relationships, which in turn cause intense distress.

With respect to primitive defences, Hartmann33 indicates that they act by distorting reality to a greater extent. This in turn increases the burden of anxiety and the deterioration of ego functions, and the loss of adaptive efficiency, flexibility and autonomy, all of which is compatible with the symptomatic manifestation of depression, anxiety and stress.34-37 The latter may be of relevance if we consider that members of the study group were at a stage in their lives that requires adaptive efficiency,37 since this involves tasks typical of the transition from adolescence to adulthood that will ultimately consolidate the individual's identity.21,22

Finally, the study design may be a limitation in itself, because solid assumptions regarding the influence of personality on other study variables cannot be made in cross-sectional studies. In view of this, a longitudinal design would be advisable for future studies, as this would allow researchers to use other techniques, such as structural interviews, to observe the appearance of symptoms in individuals with an established personality structure.

In addition, further cross-sectional studies on this topic could include sociodemographic and psychological variables that would permit statistical modelling of the occurrence of depression, anxiety and stress in a more widely representative and varied group of university students.

ConclusionsOur results confirm the correlation between personality dimensions and depression, anxiety and stress reported in a previous study conducted in Chile8 in healthcare science students, and shows that these symptoms depend to a certain extent on personality organisation.

The results are promising, in light of the fact that the majority of our students were in late adolescence, a period of life in which identity is not yet completely consolidated,21,22 and certain aspects of the personality structure of healthcare science students can still be diagnosed at an early stage, as recommended by other authors.37 Early diagnosis would allow action to be taken to strengthen the basic aspects of the personality of undergraduate students8 at a stage of life that requires adaptive efficiency. Such remedies would ultimately be expected to consolidate more robust emotional functioning and identity construction.

On the other hand, if we accept the premise that personality is a condition that exerts a relatively permanent influence, a proportion of the variance remains unexplained, and could be attributed to other environmental and individual factors1,2,11,14 that have a more contingent influence. These could be investigated in future studies in order to establish a more accurate statistical model of the combined relationship of these factors and personality in respect of depression, anxiety and stress in healthcare science undergraduates.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: RB López, NM Navarro, AC Astorga. Relación entre organización de personalidad y prevalencia de síntomas de depresión, ansiedad y estrés entre universitarios de carreras de la salud en la Región de Coquimbo, Chile. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2017;46:203–208.