This research aims to analyze the transition to the role of family caregiver (FC). The purpose of this study was: to identify factors leading the dependent person of family caregivers to the hospital urgent care (UC); to identify constraints associated with the ability to perform the FC role and difficulties experienced by FC in their ability to perform this role.

This was an exploratory, transversal, and descriptive study conducted in two stages with convenience samples. The first stage involved variables related to the dependent person and to the FC, namely to the caretaking process, in the dimensions: cognition, knowledge, perception of support, relationship with the family member, motivation, perception of physical health, perception of self-efficacy, identification of warning signs and management of the therapeutic regimen, underlying the Nursing Outcomes Classification. The study was conducted using a questionnaire delivered to each participant, 43 dependent persons and their FC. The second stage comprised a sample of 6 FC. A semi-structured thematic interview was conducted and submitted to content analysis, using the Transitions Model. Data were analyzed through descriptive and inferential statistics. The difficulties associated with the FC ability to perform were: knowledge, perception of support, motivation, perception of physical health, perception of self-efficacy, coping with the illness, coping with the suffering of the family member and fear.

Nurses must take special consideration to admissions of dependent persons cared at home by their FC. This will help to determine if the worsening of the patient's condition is due to the onset of symptoms disease related or is the result of the FC inability to deal with the dependency changes and constant demands.

Advances in medicine and the improvement of life conditions have contributed to the increase in life expectancy, and to the prevalence of chronic illnesses.1 Because people are living longer, they are also more likely to become dependent. Dependency represents a major challenge for modern societies in general and for nursing in particular, with special focus on the promotion of autonomy, self-care, and the role of the carer.

Currently, home care provision to the dependent person is considered ‘as a strategy for the promotion of autonomy and dignity’.2 This underlying assumption places the FC3 at the centre of nurses’ interventions in the promotion of quality of care.4 In addition, FC are often not prepared with the necessary knowledge and skills to meet the specific needs of the dependent person.5 The changes arising from this new role are often associated to transition experiences,6 and require the adoption of a set of adaptive strategies to better cope with these changes and the demands of the role.2

Much of the research on self-care has been informed by the theoretical perspective on transitions, with an emphasis on nursing.7 Throughout their lives, clients experience situations of commitment to self-care, which challenge their caregivers to adopt different strategies aiming to better deal with transitions.6 In the context of nursing, the concept of transition refers to a change of the health status, in the clients’ role plays, in life expectations, in skills or in the ability to manage health conditions.6 Transitions challenge people to incorporate new knowledge and new skills, influencing the person self-perception as an individual and on the health condition.6

Transitions are both predictors of change and the result of changes in the life and health status of people. They are viewed as a shift from one stage to another, from a specific condition or status to a different one.7 As a human science domain, nursing focused on the experiences and responses of individuals to health and disease, should be able to address these transitions, and identify the factors influencing change, thus helping people to experience healthier transitions.

Caregivers often refer to the imbalances experienced and which ultimately are expressed in the inability to take care for their significant relatives. The inability to overcome these constraints will likely determine ‘non-adaptive’ response patterns, feelings of loss of control and ‘displacement’. Hence, nursing professionals should focus on helping people to develop response patterns targeted at improving the health status. The inherent factors or ‘constraints’ can be categorized in three dimensions: (a) personal; (b) community; (c) society. The personal constraints can involve aspects such as cultural beliefs and attitudes or the financial situation. This category can also include previous background and acquired knowledge.7 Constraints related to transitions associated with community factors often refer to family processes or the level of support that clients are able to deliver.

In Portugal, the hospital urgent care nurses are frequently faced with situations of dependent persons on self-care, relying on the carer assistance and support, which can sometimes mean replacing the dependent person in the daily tasks. They are also aware of the complexity of the FC role and potential constraints. Thus, the urgent care nurses can work as key elements in these transition processes, as they are able to identify causes for hospital admissions, which in many cases might be closely related to FC's lack of knowledge and preparedness. As such, for a better transition process, it is important that nurses, during the patient stay in the urgent care service, also address the needs of the FC, and provide this information to nurses working in the community. This will facilitate guidance of the FC for nursing community support and consequently for a healthier transition process. By providing sufficient information, nurses will be helping the FCs to find specific support in the communities that will likely empower them with knowledge and skills and contribute to safer and effective interventions to the dependent person. Professionals should address the FC's needs, praise their efforts and provide them with information on available nursing community resources, making this transition a less stressful event.4 Thus, nurses are often the main responsible for preparing the FC to their new role and for an effective diagnostic process and autonomous decision-making, likely to determine a more adequate response to the needs of the dependent person and the FC.

The existing evidence identifies gaps in home care provision, with negative impact on quality of life of the dependent person. Hospital admissions are usually the result of less prepared FC in dealing with the onset of symptoms and change in the health condition of the dependent person, but can also be related to an ineffective formal community support. The Portuguese health care network still fails to provide the necessary support to the FC with responsive strategies to the transition hospital-home,8,9 increasing the FC concerns. Recurrent hospital readmissions are frequently unscreened. This might hinder a clear diagnosis and prevent the identification and potential prevention of causes leading to hospitalization.

Hence, this research study is aimed at mastering the transition process to the FC role by identifying its central concepts: the dependent person and the FC; and by establishing goals: through the identification of constraints on the ability to perform the FC role and the identification of the difficulties experienced by FC in their ability to perform their role.

MethodsThis was an exploratory, transversal and descriptive study, within mixed methods. The purpose was to explore the phenomenon of care provided by a family caregiver to a dependent person, to analyze and describe this process in the population under study and address some relevant issues associated with this role. The study involved variables related to the dependent person [socio-demographic characterization, use of health care services, dependency level and health status (with a 4 point Likert scale; self-care in bathing: e.g. ‘uses the shower’ – (a) the dependent person does not cooperate, 1=the worse; (b) needs help; (c) needs special equipment; (d) totally independent; 4=the best); self-care in dressing/undressing: e.g. ‘dresses the upper part of the body’; self-care in feeding: e.g. ‘takes food to his/her mouth’]. This form is part of an instrument developed by a Nursing School which has been used in different studies related to self-care and care provided to dependent persons. The study also addressed variables related to the FC, such as socio-demographic characterization and the task of caring, characterization of dimensions: cognition (e.g. clear communication process, understands the provided information, memorizes and assimilates this information?’), knowledge [e.g. ‘shows knowledge on the caregiver role (implications, function…)?’], perception of support (e.g. ‘which is the perception of the support provided by health professionals?’), relationship with the family member (e.g. ‘how do you consider the relationship with your relative?’), motivation (e.g. ‘perceived intention to interact?’), perception of physical health (e.g. ‘feels physically incapable of caring?’), perception of self-efficacy (e.g. ‘feels confident to solve problems care provision related?’), identification of warning signs [e.g. ‘identifies changes in the health condition of the family member (worsening condition signs?’)] and management of the therapeutic regimen (e.g. ‘complies to/assures commitment to the therapeutic regimen of the family member?’). All these variables are likely to influence the family caregiver's role and are informed by the Nursing Outcomes Classification.10 A questionnaire was applied to each participant using a 4 point Likert scale (1=the worse; 4=the best). A pre-test was conducted with 6 dependent persons and their respective FC (6) recruited from the Hospital Urgent Care, to establish the content validity of the questionnaire. This research was carried out in two moments, from 15/05/2012 to 30/04/2013. The first moment, which lasted six months, occurred at the Hospital Urgent Care of a central hospital in the northern region of Portugal and 43 family caregivers and 43 respective dependent persons were recruited. Additionally, nine other groups were also approached (family caregiver and dependent person), who refused to participate. During this study, all the dependent persons and respective family caregivers were approached at the time of admission to the Hospital Urgent Care. Due to the availability of the researchers, a form was applied to a convenience and non-probabilistic sample. A Cronbach's alpha value of 0.90 is described in the dependent person form, demonstrating reliability of results. The Cronbach's alpha values for the form applied to the FC varied between 0.68 and 0.92, allowing a valid analysis of the results, albeit with some constraints regarding the perception of support, with a non-statistically significant value of 0.68.

The second moment of the study involved semi-structured thematic interview conducted with a convenience sample. Participants were recruited outside the hospital context, involving 6 out of the 43 FC, with the inclusion criteria: using the Urgent Care more than two times over the previous year, as a result of the worsening of the dependent person health condition. The time and place to conduct the interview, that lasted approximately 60min, was agreed between researcher and participant and included questions such as, ‘what skills did you have when you first started caring for your family member?’; ‘did you feel prepared to provide care?’; ‘what were the difficulties found when you started providing care?’; ‘what kind of support did you sought/use?’; ‘how did you develop the ability to provide care’; ‘who is helping you?’; ‘what are the implications of caring for a family member on your personal life?’. The purpose of these interviews was to enhance this research. This convenience sample included the FC who agreed to participate in the research and not those that were considered by the researcher as potential contributors to provide better information inputs. Data processing and analysis was guided by the researchers and carried out using SPSS 21 software, through descriptive and inferential statistics and the calculation of Spearman's correlation (non-parametric statistics). The interviews were recorded and latter submitted to content analysis, using the Meleis Theory of Transitions Model.6 The study was approved by the research hospital's ethics committee prior to data collection, protocol no. 064/12(042-DEFI/062-CES), and all participants were given information on the study and signed a written consent.

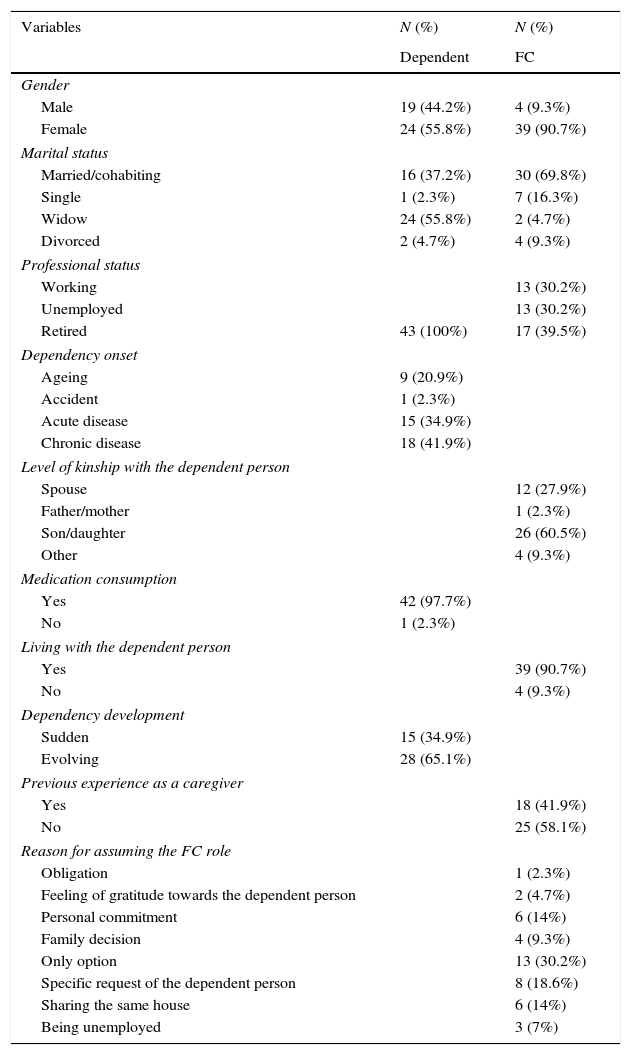

ResultsDescription of the study sampleThis research included dependent persons with a mean length of dependency of 47.95 months and a high level of dependency in self-care, with more autonomy regarding food intake and more dependent on self-care, use of wheelchair and on taking medication. The majority took prescribed medication (97.7%), with an average of 7.7% (SD=±4.24). Among other characteristics, the dependent persons showed an average age of 81.51 years (SD=±7.82) (Table 1). Reported inpatient admissions over the previous year, were on average of 1.77 times (SD=±1.54).

Characterization of the dependent and the family caregiver.

| Variables | N (%) | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent | FC | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 19 (44.2%) | 4 (9.3%) |

| Female | 24 (55.8%) | 39 (90.7%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/cohabiting | 16 (37.2%) | 30 (69.8%) |

| Single | 1 (2.3%) | 7 (16.3%) |

| Widow | 24 (55.8%) | 2 (4.7%) |

| Divorced | 2 (4.7%) | 4 (9.3%) |

| Professional status | ||

| Working | 13 (30.2%) | |

| Unemployed | 13 (30.2%) | |

| Retired | 43 (100%) | 17 (39.5%) |

| Dependency onset | ||

| Ageing | 9 (20.9%) | |

| Accident | 1 (2.3%) | |

| Acute disease | 15 (34.9%) | |

| Chronic disease | 18 (41.9%) | |

| Level of kinship with the dependent person | ||

| Spouse | 12 (27.9%) | |

| Father/mother | 1 (2.3%) | |

| Son/daughter | 26 (60.5%) | |

| Other | 4 (9.3%) | |

| Medication consumption | ||

| Yes | 42 (97.7%) | |

| No | 1 (2.3%) | |

| Living with the dependent person | ||

| Yes | 39 (90.7%) | |

| No | 4 (9.3%) | |

| Dependency development | ||

| Sudden | 15 (34.9%) | |

| Evolving | 28 (65.1%) | |

| Previous experience as a caregiver | ||

| Yes | 18 (41.9%) | |

| No | 25 (58.1%) | |

| Reason for assuming the FC role | ||

| Obligation | 1 (2.3%) | |

| Feeling of gratitude towards the dependent person | 2 (4.7%) | |

| Personal commitment | 6 (14%) | |

| Family decision | 4 (9.3%) | |

| Only option | 13 (30.2%) | |

| Specific request of the dependent person | 8 (18.6%) | |

| Sharing the same house | 6 (14%) | |

| Being unemployed | 3 (7%) | |

The FC sample comprised women (90.7%), Table 1, with an average age of 59.07 years (SD=±13.34) and caring for the dependent person, on average, for 47.44 months (SD=±39.26), with approximately 19.33h per day spent in daily tasks. From the total sample, 39.5% were retired and 30.2% were still employed. The children (60.5%) and spouses (27.9%) of the dependent persons were found to be the main caregivers. For 30.2% of the cases there was no other available option and in 18.6% of the cases this followed a direct request of the dependent person. The results also highlighted that 58.1% of FC had no previous experience as carers. Family caregivers included in this sample revealed high perception of self-efficacy (3.16) and low perception of physical health (2.16).

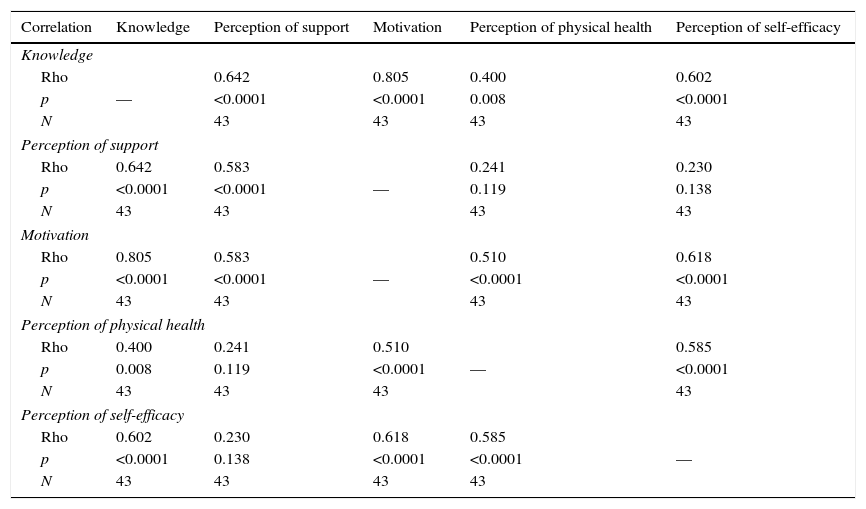

Relationships between variablesFrom the analysis on the relationship between the variables, calculated according to the Spearman correlation coefficient, it was found that the number of hospitalisations over the previous year had been greater for younger dependent persons (rs=−0.316; n=43; p=0.039) and in dependent persons using more drugs (rs=0.327; n=43; p=0.032). It was also observed that a greater level of dependency in self-care meant a greater level of dependency on the remaining variables (p<0.0001). FC caring for older dependent persons were found to have a better perception of physical health (rs=0.407; n=43; p=0.007) and the greater the number of drugs used by the dependent person, the better the level of knowledge (rs=0.395; n=43; p=0.009), perception of support (rs=0.313; N=43; p=0.041) and motivation (rs=0.332; n=43; p=0.029) of FC. Also, as shown in Table 2, the better informed FC were, the better was the perception of support (rs=0.642; n=43; p<0.0001), greater motivation (rs=0.805; n=43; p<0.0001), better perception of physical health (rs=0.400; n=43; p=0.008) and better perception of self-efficacy (rs=0.602; n=43; p<0.0001). Higher motivation levels and knowledge in FC determined better perception of support (rs=0.583; n=43; p<0.0001), better perception of physical health (rs=0.510; n=43; p<0.0001) and better perception of self-efficacy (rs=0.618; n=43; p<0.0001). Moreover, FC with better perception of self-efficacy also showed better perception of their physical health (rs=0.585; n=43; p<0.0001).

Correlation between the dimensions of the Family Caregiver.

| Correlation | Knowledge | Perception of support | Motivation | Perception of physical health | Perception of self-efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | |||||

| Rho | 0.642 | 0.805 | 0.400 | 0.602 | |

| p | — | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.008 | <0.0001 |

| N | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | |

| Perception of support | |||||

| Rho | 0.642 | 0.583 | 0.241 | 0.230 | |

| p | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | — | 0.119 | 0.138 |

| N | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | |

| Motivation | |||||

| Rho | 0.805 | 0.583 | 0.510 | 0.618 | |

| p | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | — | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| N | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | |

| Perception of physical health | |||||

| Rho | 0.400 | 0.241 | 0.510 | 0.585 | |

| p | 0.008 | 0.119 | <0.0001 | — | <0.0001 |

| N | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | |

| Perception of self-efficacy | |||||

| Rho | 0.602 | 0.230 | 0.618 | 0.585 | |

| p | <0.0001 | 0.138 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | — |

| N | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | |

The calculation of the correlation between the FC's dimensions and the level of dependency in self-care was only statistically significant when the variable of perception of self-efficacy was associated with the variable of dependency in self-care: bathing (rs=0.310; n=43; p=0.043), dressing/undressing (rs=0.326; n=43; p=0.033), getting ready (rs=0.303; n=43; p=0.049) and using the bathroom (rs=0.323; n=43; p=0.035). Thus, these findings showed that perception of self-efficacy of the FC positively correlated with the dependent person's autonomy in self-care.

It was also found that the lower the number of pressure ulcers of the dependent person, the higher the level of knowledge (rs=−0.319; n=43; p=0.037), perception of support (rs=−0.304; n=43; p=0.048) and perception of self-efficacy (rs=−0.405; n=43; p=0.007) of the FC. Correlation was also found between the number of pressure ulcers and the dependency level in self-care. As an example, the use of the toilet showed a correlation of (p=0.009). The results show that the number of pressure ulcers is lower for people less dependent on self-care.

Studying the phenomenon of caring for dependent persons by the FCRegarding the transition properties, 3 categories were identified: Awareness: ‘Now I need more help since he cannot move and I can’t do it all by myself’, which set the beginning of the transition process, and was identified after FC perception on the increase of their family member dependency; Involvement, which included two subcategories: observation/explanations of nurses: ‘I was watching the nurses as they took care of her…’ and consultation of the websites: ‘I searched the internet for information’; and the Changes associated with the FC role, with the subcategories: unemployment: ‘I’m unemployed…’, decreased leisure time: ‘there are certain things I had to stop doing…’, hiring paid support: ‘since I decided to care for with my mother I had to hire a person’, decreased free time: ‘I have less available time for myself’, decreased sleep: ‘I’ve no spare time, not even to get some sleep’, neglecting self-health condition: ‘I’ve been neglecting my own health’, and no vacation: ‘since my father got ill I stopped going on vacations’.

As to the transition conditions (factors inhibiting and/or facilitating the transition), from the analysis of the recorded interviews, 6 categories and respective subcategories emerged. Prior preparation was one of the categories found, with the subcategories: previous experience in caring: ‘I took care of a person, so it was easier for me to care for my mother’ and access to relevant information in caring/preparation: ‘The hospital nurses taught me what to do’. The motivation to take care included the subcategories: affection, obligation, duty, retribution, feeling of being the only one able to take care; only option and refuse to abandon, e.g.: ‘I feel this is my duty’; ‘no other son offered to help’. The category caretaking referred to: feeling of comfort: ‘It's rewarding to feel I’m doing all I can’, sense of conscience: ‘I feel relieved…’, feeling gratified: ‘despite all, it's truly gratifying’ and feeling rewarded: ‘it's difficult but also rewarding’. In the category of barriers to the FC role, the following subcategories emerged: doubt, low perception of self-efficacy, fear of insufficient financial resources, fear caused by increased responsibility, coping with the clinical diagnosis/illness, coping with stress, fatigue, fear, and roles overlap, e.g. ‘I was completely scared’; ‘the emotional suffering is tremendous and very difficult to cope with’. The categories of financial capacity: ‘it's difficult since I’ve to pay for everything’ and support for care: ‘my sister also helps me’, were also identified.

Concerning the response patterns, 3 categories and respective subcategories were identified, which allowed a better understanding on how FC adapted to their new role. Interaction with nurses was one of the categories that emerged with related subcategories: clarification of doubts: ‘I was constantly asking nurses’ and observation on how the nurses performed their work: ‘and watch them doing it’. The self-perception of efficacy comprised: safety in the provision of care: ‘I feel more confident’, perception of positive performance development: ‘I know that I’m better in what I do’, decreased initial fears: ‘my initial fears have faded’, perception of being prepared to provide care: ‘I feel fully prepared’ and the ability in provision of care related problem-solving: ‘I don’t panic anymore’. And finally, the category development of adaptive strategies, expressed mostly through: the maintenance of leisure activities: ‘I’ve always tried to keep some personal activities’, incorporation of care into daily life: ‘I try to manage time my own way’ and inclusion of the dependent person in the leisure activities: ‘we have all been going on vacations since she's not yet confined to a bed’.

It was not possible to identify reasons for urgent care admissions involving the person dependent on family caregivers, since the relationship established between the variable “number of hospital admissions in the previous year” and the remaining variables under analysis did not show significant statistical correlations.

DiscussionThis study identified a profile of FC similar to other studies conducted in Portugal.11,12

Constrains associated with the ability to perform the FC roleThe constrains associated to the ability to perform the FC role identified throughout this research were related to factors that could act as facilitators or inhibitors. The dependent person's age and level of dependency were two factors that may condition the ability to perform the FC role. Data also revealed that FC caring for older dependent persons showed a better perception of physical health (p<0.01), very likely to have a positive impact on the ability to perform their role. Also, the level of dependency influenced the FC perception of self-efficacy, which increased when higher levels of self-care autonomy were found in the dependent person, like bathing, dressing/undressing, getting ready and using the bathroom (p<0.05). Evidence was also found that demonstrates that a lower level of dependency will be a facilitator to provide care. In a different study, involving Alzheimer patients, no statistical correlation was found when trying to establish relationship between the quality of life of the carer and the level of dependency of the patients.13

This study enabled to identify constrains related to FC: knowledge,14–16 motivation,14 perception of support,14,17,18 perception of self-efficacy,14 caretaking,19 financial capacity14 and difficulties encountered.

The level of knowledge of FC was considered an important constraint to the ability to perform the FC role, since FC with more knowledge had better perception of support, greater motivation, better perception of physical health and better perception of self-efficacy (p<0.01). A Portuguese study conducted on the phenomenon of caring for family members, revealed that, in many readmissions FC showed frailties in terms of knowledge and skills.15 On the other hand, dependent persons whose FC had greater knowledge, suffered from fewer pressure ulcers (p<0.05), suggesting that good knowledge levels of the FC are likely to facilitate and promote an adequate performance.20

This research also found that more motivated FC also perceived better support, better physical health and better self-efficacy (p<0.0001), which might suggest that motivation is a facilitator of the caretaking process. This finding corroborates the results from another study,14 referring to motivation as the driving force of FC. The perception of support by FC was found to be inversely proportional to the number of pressure ulcers of the dependent person (p<0.05). This finding might reveal a considerable constraint to FC, since they reported to be very reliant on the observation and explanations of nurses,17 as well as websites information.

The FC perception of self-efficacy may also condition the ability to perform the FC role,14 since an FC with a better perception of self-efficacy has improved perception of physical health (p<0.0001) and the dependent person has fewer pressure ulcers (p<0.01). All of the interviewed FC gave a positive meaning to caring for a family member, which seems to constitute a facilitator, thus promoting the role performance.19 The barriers faced by FC during the course of the caretaking process may also be seen as restrictions to the ability to perform the FC role and may have a considerable negative impact.

The financial capacity can also be an additional burden to FC while caring for the dependent person.14 FC professional occupation is often very demanding and it is very likely to interfere with the caring process, also because of the increased fear caused by potential unemployment.17 Lower financial capacities will then hinder FC leisure opportunities that could likely provide relief to the FC while caring for the dependent person. A low income, associated with increased care costs, might increase the financial burden, and diminish the possibility of hiring paid support.17

Difficulties experienced by FCRegarding the difficulties experienced by FC in their caretaking process, the ones showing higher percentage (over 50% of the sample between scores 1 and 2) were identified, which were based on the data analysis from the participating FC and from the additional information extracted from the interviews. Thus, the following items were identified: knowledge,14,16 perception of support,14,18 motivations,14 perception of physical health,16,21 perception of self-efficacy,19,22 dealing with the clinical diagnosis/illness, coping with the suffering of the family member and fear.

In what concerns knowledge, the difficulties found were mainly focused on: actions in urgent care situations (53.7%); knowing the community available resources (58.1%) and knowing how to make use of them (62.8%);14 knowing the equipment necessary to the family members (67.5%) and doubts2 concerning aspects related to care.

As for the perception of support, the difficulties included: the support of family members, friends and neighbours (81.4%)14; financial resources (79.1%)14; sharing the responsibility of caring between family members (76.8%)14; access to support equipment (53.5%); fear of the responsibility and roles overlapping. FC considered extremely important the support (paid or unpaid) provided in the caring process, paid or unpaid, since caretaking is often a both physically and emotionally exhausting task.14,17 However, results suggested that it is not easy to access this support, which is why the care is often provided by a single person.

Concerning motivation, the greatest difficulty identified was related to making plans for the future, including planning vacations, commonly referred by the majority of participants (97.7%).14 The caretaking process of a dependent person implies the reorganization of the FC daily living and often leads to reduced availability of time for oneself, for leisure and for vacations.17,23 Guilt was also found to undermine time availability, since FC find themselves incapable of leaving the dependent person: “ever since my father became sick, I’ve never went on vacation. I can’t go, we can’t get around this question” (E4). When accessing the perception of physical health, FC reported several difficulties: the physical limitation to provide care (69.7%); the functional ability to provide care (60.5%); and the strengths to provide care (81.4%).14,24

Concerning the self-perception on efficacy, the problem-solving related to the provision of care (58.1% of the sample), and the low perception of self-efficacy were the most highlighted difficulties.19,22 Other difficulties included coping with the illness and the suffering of the dependent person and also the fear associated with the task of caring. Facing the disease was considered a critical event, essentially due to the fear of its progression and consequences in the family member's autonomy, often associated to the difficulty to manage signs and symptoms. The perception of the dependent person's suffering was referred as a considerable burden, causing fatigue to the FC, as well as the initial fear of being unprepared for this new role.

ConclusionsThis study results suggest that nurses working in the hospital Urgent Care are constantly faced with situations of families caring for a dependent person, a task for which many FC are still poorly prepared. Becoming a FC triggers a transition process that needs monitoring and supervision and nurses play an important role in helping the FC to feel empowered and encouraged to better care for the dependent person. Promoting nurses’ awareness is a major issue and should be included in the dependent persons’ care planning process.

This study highlights the importance of increased knowledge and skills, as crucial aspects interfering in nurses’ practice. This study results also give noteworthy contribution to promote a closer relationship between FC and nurses, enabling a better and healthier transition to the new FC role.

Authorship statementThe authors confirm that they meet the authorship criteria and are all in agreement with the content of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.