Cachexia affects the majority of patients with advanced cancer and no effective treatment is currently available to address this paraneoplastic syndrome. It is characterized by a reduction in body weight due to the loss of white adipose tissue (WAT) and skeletal muscle. The loss of WAT seems to occur at an earlier time point than skeletal muscle proteolysis, with recent evidence suggesting that the browning of WAT may be a major contributor to this process. Several factors seem to modulate WAT browning including pro-inflammatory cytokines; however, the underlying molecular pathways are poorly characterized.

Exercise training is currently recommended for the clinical management of low-grade inflammatory conditions as cancer cachexia. While it seems to counterbalance the impairment of skeletal muscle function and attenuate the loss of muscle mass, little is known regarding its effects in adipose tissue. The browning of WAT is one of the mechanisms through which exercise improves body composition in overweight/obese individuals. While this effect is obviously advantageous in this clinical setting, it remains to be clarified if exercise training could protect or exacerbate the cachexia-related catabolic phenotype occurring in adipose tissue of cancer patients. Herein, we overview the molecular players involved in adipose tissue remodelling in cancer cachexia and in exercise training and hypothesize on the mechanisms modulated by the synergetic effect of these conditions. A better understanding of how physical activity regulates body composition will certainly help in the development of successful multimodal therapeutic strategies for the clinical management of cancer cachexia.

Cancer cachexia (CC) is a syndrome associated with poor prognosis, being responsible for about 20% of deaths in cancer patients.1 This paraneoplastic syndrome is characterized by a hypermetabolic state that leads to the loss of adipose tissue and skeletal muscle.2,3 Hormones, cytokines and other factors secreted by the tumour have been suggested to cause unbalanced energy expenditure, negative protein balance and increased lipolysis.4–6 Deregulation of hypothalamic mechanisms controlling energy wasting, hunger and satiety have also been associated with CC, suggesting that neuroendocrine processes can regulate adipose tissue and skeletal muscle wasting.1,4 Remodelling of adipose tissue seems to occur at an earlier time point than muscle proteolysis in CC. This is characterized by the browning of white adipose tissue (WAT) that leads to lipid mobilization/oxidation and heat production.1,7,8 Whereas increased proteolysis seems to explain muscle wasting, elevated lipolysis has been reported to be the main cause of adipose tissue loss in cancer patients.9 Nevertheless, the molecular pathways behind WAT adaptation to CC are poorly characterized.

Exercise training has been suggested as a preventive and therapeutic strategy for CC mostly because it prevents or counteracts muscle loss.10,11 However, the impact of exercise training on CC-related WAT remodelling is poorly comprehended. In this review we overview the molecular pathways involved in CC-related WAT remodelling and the putative impact of exercise training on this process.

WAT remodelling in cancer and involved molecular playersThe CC-related alterations in the metabolism of adipose tissue include changes in the expression of genes with regulatory roles in the browning of WAT, a process by which WAT is converted into brown adipose tissue (BAT).12 Both WAT and BAT participate in the regulation of energy balance but while WAT is mainly involved in the maintenance of energy homeostasis by storing energy in the form of triglycerides, BAT is responsible for thermogenesis through lipid oxidation.13

Until recently, BAT was believed to be only present in neonatal and childhood periods whereas WAT is distributed all over the body.14 Nowadays, depots of BAT are recognized to persist in adults which correlates with their leanness.15 In CC, the presence of BAT was firstly noted when the use of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scanning was introduced in the routine clinical practice for cancer staging.16,17 This methodological approach works by monitoring glucose uptake and so it is not surprising that some non-tumour tissues utilizing glucose are also labelled. In fact, besides the labelling of brain, heart and bladder, some additional areas of glucose uptake were observed by PET, particularly in the neck and shoulder area. This was later attributed to BAT.18 FDG uptake by BAT in adulthood implies the existence of thermogenically active adipose tissue, suggesting its involvement in energy wasting. So, FDG-PET seems an attractive non-invasive approach to determine BAT activity, supporting routinely employed clinical PET imaging to be extended to the diagnosis of patients at risk of CC.

WAT adipocytes are bigger than BAT adipocytes and have an unilocular morphology while BAT adipocytes present a multilocular morphology.19,20 BAT has a large density of mitochondria and is among the most vascularized tissues of the body, which confer its characteristic brown colour.19 Another type of adipocytes named brite (or beige) adipose cells were recently reported. These cells are located in WAT tissue in both subcutaneous and trunk compartments, and have the same thermogenic function of BAT cells. While brite adipocytes could be perceived as the result of ‘transdifferentiation’ of WAT to BAT in response to certain stimuli, there is also the suggestion that beige adipocytes are a new type of adipocytes derived from progenitors distinct from WAT and BAT.21,22

Browning of WAT in CC can be triggered by several factors, including sympathetic nervous system (SNS) signals that activate β3 adrenoceptors.13,23,24 Consequently, there is an overexpression of zinc-α2-glycoprotein (ZAG), which activates a G-coupled receptor with the consequent activation of hormone sensitive lipase (HSL) and the release of glycerol and free fatty acids (FFAs) from adipocytes.23 ZAG is one of the best described adipokines involved in CC-related WAT browning.4,24 Other adipokines are secreted by BAT such as leptin, adiponectin and resistin.25 The role of leptin in CC is not clear. In most studies the levels of this adipokine are positively correlated with body mass index (BMI), suggesting that low levels simply reflect diminished fat mass.26 However, these low leptin levels did not seem to result in increased appetite and decreased energy expenditure as expected. Thus, hypothalamic insensitivity to the low circulating levels of leptin have been speculated to occur in CC.27 Circulating adiponectin concentrations were inversely correlated with both free and total leptin concentrations in cancer patients suggesting that adiponectin antagonizes the effect of leptin after weight loss.28 Indeed, adiponectin concentration was reported to be significantly higher in cachectic patients when compared with stable weight patients.29 Higher production of adiponectin in CC seems to contribute to the wasting process, as adiponectin administration in experimental animal models was shown to increase energy expenditure.30 However, some authors have suggested that catabolic reactions and uncontrolled energy consumption in CC may contribute to adipose tissue degradation and to the reduction of adiponectin expression.31 Resistin is an adipose tissue derived hormone, also termed “adipocyte secreted factor” (ADSF) or “found in inflammatory zone” (FIZZ3).32 Despite its association to a variety of inflammatory and autoimmune processes, and to increased cancer risk, the association of resistin with body weight, appetite and insulin resistance is not clear.27 Indeed, the majority of the studies on CC did not report a correlation between resistin and fat mass.33,34

BAT also produces other substances as a result of its endocrine activity, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).25 By promoting a dense vascular network, VEGF, particularly VEGF-A, indirectly supports the high-energy consumption of BAT.35,36 Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 21, a protein originally known to be expressed by the liver in response to fasting, is secreted by BAT, especially during thermogenic activation.25 Parathyroid-hormone related protein (PTHrP) was also involved in WAT browning.37 Indeed, higher serum levels of this protein were associated with weight loss in cancer patients.38 Fat-specific knockout of PTHrP was reported to prevent adipose browning and also to preserve muscle mass and improve muscle strength.39

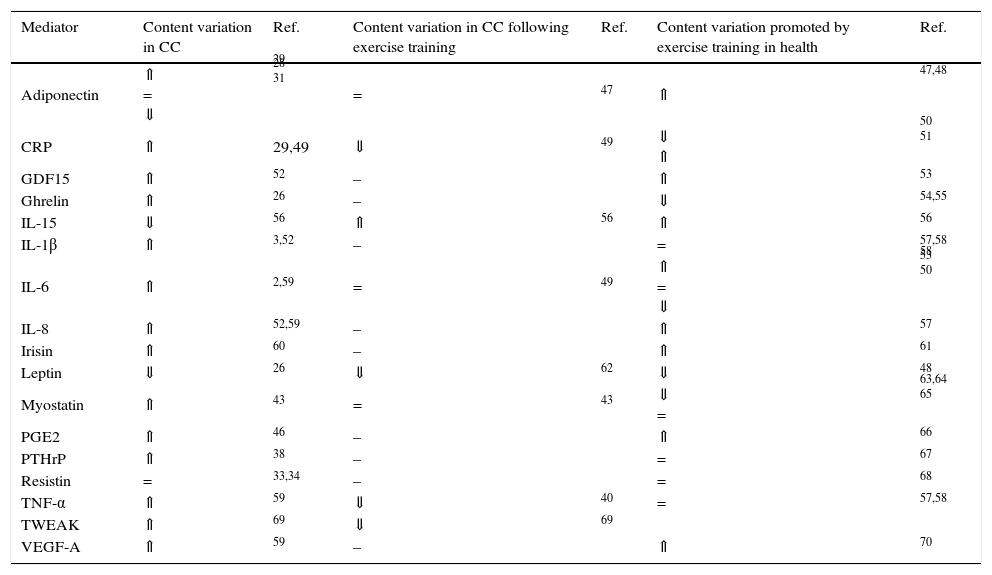

WAT is a contributor to systemic inflammation, as adipocytes and infiltrating inflammatory cells, primarily macrophages, produce inflammatory mediators, initiating a negative set of effects in the adipose tissue function, including the death of adipocytes.40 For instance, TNF-α inhibits lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity, increases HSL mRNA expression and reduces GLUT4 expression, leading to reduced glucose transport and consequently to a decline in glucose availability for lipogenesis.41 TNF-α also increases the expression of chemoattractant protein 1, attracting monocytes to the adipose tissue.42 The resulting inflammatory response leads to the recruitment of macrophages that produce TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β, increasing macrophage recruitment, perpetuating this vicious cycle.42 IL-6 might enhance thermogenesis acting directly on BAT or indirectly through the stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system.2 The cytokine TNF-related weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) secreted by the tumour was also associated to cachexia.43,44 However, inconsistent results have been reported regarding the CC-related levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which might be justified by the transient nature of its secretion, cancer stage or distinct assays sensitivities. Besides cytokines, inflammatory-induced prostaglandins have also been proposed as key mediators of CC. Among prostaglandins, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) seems to be involved in CC once inhibition of the inducible cyclooxygenase (COX-2) prevents body weight loss.45. Indeed, higher levels of PGE2 were reported in cancer patients with cachexia.46. Table 1 overviews the most described circulating mediators involved in CC-related WAT remodelling.

Circulating mediators modulated by cancer cachexia (CC) and/or exercise training.

| Mediator | Content variation in CC | Ref. | Content variation in CC following exercise training | Ref. | Content variation promoted by exercise training in health | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adiponectin | ⇑ = ⇓ | 29 28 31 | = | 47 | ⇑ | 47,48 |

| CRP | ⇑ | 29,49 | ⇓ | 49 | ⇓ ⇑ | 50 51 |

| GDF15 | ⇑ | 52 | – | ⇑ | 53 | |

| Ghrelin | ⇑ | 26 | – | ⇓ | 54,55 | |

| IL-15 | ⇓ | 56 | ⇑ | 56 | ⇑ | 56 |

| IL-1β | ⇑ | 3,52 | – | = | 57,58 | |

| IL-6 | ⇑ | 2,59 | = | 49 | ⇑ = ⇓ | 58 53 50 |

| IL-8 | ⇑ | 52,59 | – | ⇑ | 57 | |

| Irisin | ⇑ | 60 | – | ⇑ | 61 | |

| Leptin | ⇓ | 26 | ⇓ | 62 | ⇓ | 48 |

| Myostatin | ⇑ | 43 | = | 43 | ⇓ = | 63,64 65 |

| PGE2 | ⇑ | 46 | – | ⇑ | 66 | |

| PTHrP | ⇑ | 38 | – | = | 67 | |

| Resistin | = | 33,34 | – | = | 68 | |

| TNF-α | ⇑ | 59 | ⇓ | 40 | = | 57,58 |

| TWEAK | ⇑ | 69 | ⇓ | 69 | ||

| VEGF-A | ⇑ | 59 | – | ⇑ | 70 |

⇑ higher content; ⇓ lower content; = no content alterations; – not known.

The main molecular sign of WAT browning is the overexpression of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1). The brite cells formed in WAT are capable of performing thermogenesis because they contain pockets of UCP1-expressing multilocular cells.25,37 UCP1 is a long chain fatty acid-activated protein, highly selective for brown and beige adipose cells, that sits in the inner membrane of mitochondria.20 The thermogenic effect of this protein is due to the deviation of mitochondria from its function of ATP production by mediating proton leakage across the inner mitochondrial membrane71, not allowing the protons to be used in the process of ATP synthesis.20 Consequently, there is a decrease in energy production and an increase in heat production triggered by increased lipid mobilization, oxidation and energy expenditure.13 Released FFAs are used not only as oxidative substrates to lipogenesis but are also potent activators of UCP1 expression, which is mediated by PKA-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling pathway.25

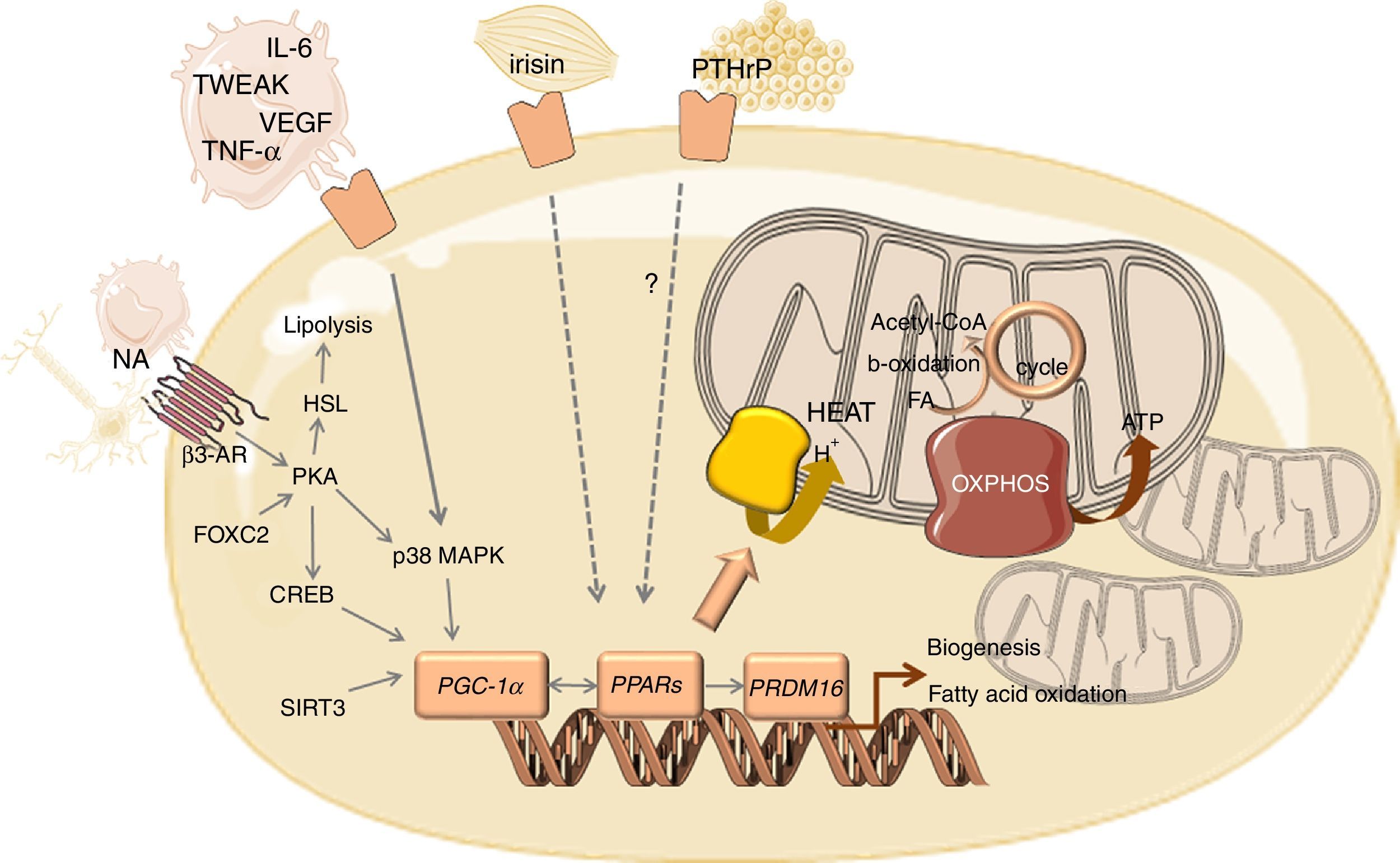

The overexpression of UCP1 that characterizes browning of WAT goes together with mitochondrial biogenesis, which is mediated by the transcriptional coactivator PPARγ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) (Fig. 1). PGC-1α might be activated by the PKA/CREB pathway or by the β-adrenergic/cAMP pathway through p38 MAPK, which counteracts p160-mediated repression and increases PGC-1α stability.72,73 Several other factors positively regulate PGC-1α transcription such as forkhead box protein C2 (FOXC2) and sirtuin 3 (SIRT3).74 SIRT3 is overexpressed in BAT, in contrast to its low expression in WAT, being required for brown adipocytes to respond to PGC1α-related thermogenic activation. Indeed, PGC-1α/SIRT3 axis seems to be important for brown adipocytes, similarly to what has been observed in other cell types with high mitochondrial plasticity.75 In addition, PGC-1α coactivates nuclear respiratory factors 1 and 2 (NRF1 and NRF2), with the consequent overexpression of genes encoding for respiratory chain subunits and other factors important for mitochondrial functionality.72 PGC-1α also increases the expression and activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and other transcriptional factors that regulate the expression of genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation and thermogenesis.76,77 The stimulation of PPARγ was reported to enhance fatty acid transport into the mitochondrial matrix, fatty acid oxidation and oxygen consumption, which occurs in tandem with increased mitochondrial density.78 PPARα seems to act as a key component of brown fat thermogenesis by the induction not only of PGC-1α but also of PR- (PRD1-BF-1-RIZ1 homologous) domain containing protein (PRDM16).76 PRDM16 is a transcriptional regulator that stimulates brown adipogenesis by activating a broad program of brown fat differentiation.79,80 Indeed, PRDM16-expressing cells consume very high oxygen amounts due to uncoupled respiration, the classic hallmark of BAT.80 Other regulators of BAT differentiation include p53, pRB and C/EBPβ.81 Whereas pRB and C/EBPβ are required for adipogenesis and regulation of mitochondrial capacity, p53 seems to inhibit adipose conversion.82,83

Overview of the mediators and signalling pathways underlying WAT browning in cancer cachexia.

Abbreviations: AR, adrenergic receptor; CREB, cAMP response element-binding protein; FA, fatty acid; FOXC2, forkhead box protein C2; HSL, hormone sensitive lipase; IL, interleukin; MAPK, mitogen activated kinase; NA, noradrenaline; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation; PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha; PKA, protein kinase A; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; PRDM16, PR- (PRD1-BF-1-RIZ1 homologous) domain containing protein 16; PTHrP, parathyroid-hormone related protein; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor alpha; TWEAK, tumour necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis; UCP1, uncoupling protein 1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Physical activity has been reported to prevent and even counteract cachexia by improving whole-body metabolic status and modulating the inflammatory response.10 Consequently, skeletal muscle proteolysis is prevented, protein synthesis is stimulated and muscle mass is preserved.10,69 Indeed, adaptations in skeletal muscle are considered central to the anti-CC effect of exercise training. Less characterized are the mechanisms underlying the remodelling of adipose tissue promoted by exercise training in CC. In fact, if exercise training promotes remodelling of WAT in CC by the same mechanisms observed in obesity, exercise training is expected to potentiate CC-related WAT browning with impact on body weight.

Repeated bouts of exercise over a period of days, weeks, or even years, were reported to modulate WAT morphology and biochemical properties, independently of significant changes in weight loss. The adipocyte size and lipid content decreases following exercise training, resulting in reduced adiposity.84 However, these changes promoted by exercise training are dependent on WAT depots’ location, being subcutaneous WAT more responsive to physical activity. Indeed, Stanford et al.85 found that only 11 days of voluntary wheel running increased UCP1 content and resulted in the presence of multilocular cells in the subcutaneous WAT, which is consistent with tissue beiging. The number of blood vessels and the content of markers of vascularization as VEGFA and PGDF also increased in the subcutaneous WAT from exercised animals. This effect was hypothesized to be mediated by increased sympathetic innervation or by the interplay with other tissues responsive to exercise training. Indeed, moderate to high intensity endurance training leads to increased activity of SNS, resulting in higher levels of catecholamines and, consequently, in a marked increase of the thermogenic capacity of adipose tissue.86 Moreover, during exercise training, irisin is released from skeletal muscle by myocytes and leads to thermogenesis by promoting the browning of WAT. Exercise increases irisin by up-regulating PGC-1α expression in skeletal muscle.62 However, the role of irisin is still of great controversy because its precursor, the fibronectin domain containing protein 5 (FNDC5), and circulating irisin have not been consistently increased with endurance exercise in humans. This might be somehow related to a number of drawbacks in the detection of irisin with ELISA kits.87 Myostatin, initially characterized as a potent inhibitor of skeletal muscle growth, seems to regulate the metabolic phenotype of other tissues as adipose tissue.88 Loss of myostatin signalling in white adipocytes promotes the development of a brown adipose tissue-like phenotype through enhancing FNDC5 expression in these cells.89 Likewise, leptin has been shown to negatively regulate irisin-induced WAT browning.90 Musclin, also known as “exercise hormone” is a peptide secreted to bloodstream by skeletal muscle in response to exercise. It has been suggested that musclin activates PPAR¿ and mitochondrial biogenesis, which induces WAT browning.7 Indeed, several reports highlight the impact of exercise training on mitochondria biogenesis and functionality. For instance, 8 weeks of swimming promoted the increase of respiratory chain complex cytochrome c oxidase and of the tricarboxylic acid cycle enzyme malate dehydrogenase in visceral WAT.91 Eleven days of voluntary wheel running was reported to increase basal rates of oxygen consumption rates in subcutaneous WAT.85 Changes in mitochondrial gene expression in subcutaneous WAT occur in response to several modalities of exercise, as well as to various training program durations ranging from as few as 11 days to up to 8 weeks.84

The interplay between cancer cachexia and exercise trainingIn the set of cancer cachexia, the therapeutic effect of exercise training has been mostly associated to its anti-inflammatory role.11,92 Substantial evidences collectively demonstrate the positive effects of exercise training on chronic inflammation through a reduction in circulating pro-inflammatory biomarkers. The anti-inflammatory ratio IL-10/TNF-α was reported to increase following exercise training in tumour-bearing animals, favouring an anti-inflammatory environment in adipose tissue.47,56 The levels of IL-15 also increased in these animals following 6-weeks of treadmill exercise training with consequent anabolic effects.56 Lifelong moderate intensity exercise training was shown to reduce C-reactive protein (CRP) in a preclinical model of mammary tumourigenesis, though without substantial evidences of modulation of other pro-inflammatory markers, including IL-6 and TNF-α (Table 1).49 The circulating levels of IL-6 are expected to increase following exercise and the magnitude of change on its levels is related to exercise intensity, duration and endurance capacity.58 The major contributor to this IL-6 increase after exercise are not monocytes93 but contracting skeletal muscle and, in smaller amounts, adipose tissue and brain.58,94,95 Nevertheless, IL-6 responsive to exercise training has an anti-inflammatory effect once inhibits TNF-α and IL-1 production96 and increases IL-1ra and IL-10.97 Chronic exercise training was also reported to prevent the mammary tumourigenesis-related increase of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TWEAK, with impact in body wasting.69 This positive effect of exercise training was associated to decreased tumour weight98 and less malignant lesions in rats.49 So, the enhancement of immune system in tumour-bearing animals seems to be among the mechanisms regulated by exercise training with impact on tumour growth and malignancy.

The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise training might also counteract or prevent anorexia that accompanies cachexia syndrome, improving body composition. This effect is reflected in the circulating levels of appetite-regulating hormones such as ghrelin. Ghrelin is an orexigenic hormone mostly synthesized in the stomach and activated by acylation through the addition of an octanoyl group in the stomach and small intestine.55 Exercise training reduces or circumvents the cachexia-related ghrelin resistance by promoting positive changes in the intracellular signalling pathways, especially in the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. So, ghrelin becomes more effective in enhancing growth hormone release and stimulating central appetite drive.55,99 Ghrelin also inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines expression in endothelial cells.100 It has been hypothesized that the combination of pharmacological ghrelin with exercise training might exert an anabolic role or, at least, arrest cachexia-related catabolism.99 Exercise training also increased the circulating levels of anorexigenic hormones such as the gut hormone peptide tyrosine tyrosine (PYY3–36), in an intensity-dependent manner.55 Nevertheless, the mechanisms underlying the effect of exercise training on these appetite-regulating hormones are not well understood and even less in the set of cancer cachexia.

ConclusionsThere is a general awareness of the health benefits of physical activity, evidenced by ongoing clinical trials that include exercise programs in multimodal management of cachexia along with pharmacological approaches. Despite the protective effect of exercise training against low-grade chronic inflammatory conditions as cancer cachexia, the synergy between these two conditions in the modulation of adipose tissue remodelling and, consequently, in the regulation of body composition remains elusive. Indeed, both conditions promote WAT browning but distinct mechanisms are probably involved. Whereas cancer cachexia-related beiging occurs in an inflammatory milieu, exercise-induced browning is associated with lower circulating levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. So, one might suspect on the activation of distinct signalling pathways in adipocytes. Future studies should address this issue by starting to characterize and compare the signalling pathways involved in adipose tissue remodelling in cancer setting and cancer plus exercise training. A better understanding of how exercise intensity and workload regulate body composition across sexes, life stages and disease grades will certainly help in the development of more successful therapeutic strategies for the clinical management of this paraneoplasic syndrome.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This work was supported by Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), European Union, QREN, FEDER and COMPETE for funding the QOPNA (UID/QUI/00062/2013), CIAFEL (UID/DTP/00617/2013), UnIC (UID/IC/00051/2013) research units, R.V. (IF/00286/2015), R.N.F (SFRH/BD/91067/2012) and D.M.G (SFRH/BPD/90010/2012).