The aim of our study is to describe the types of dementia found in a series of patients and to estimate the level of agreement between the clinical diagnosis and post-mortem diagnosis.

Material and methodsWe conducted a descriptive analysis of the prevalence of the types of dementia found in our series and we established the level of concordance between the clinical and the post-mortem diagnoses. The diagnosis was made based on current diagnostic criteria.

Results114 cases were included. The most common clinical diagnoses both at a clinical and autopsy level were Alzheimer disease and mixed dementia but the prevalence was quite different. While at a clinical level, prevalence was 39% for Alzheimer disease and 18% for mixed dementia, in the autopsy level, prevalence was 22% and 34%, respectively. The agreement between the clinical and the autopsy diagnoses was 62% (95% CI, 53%-72%).

ConclusionsAlmost a third of our patients were not correctly diagnosed in vivo. The most common mistake was the underdiagnosis of cerebrovascular pathology.

Describir los tipos de demencia en una serie de pacientes valorados en una clínica psicogeriátrica y estimar el grado de acuerdo entre el diagnóstico clínico y el anatomopatológico.

Material y métodosRealizamos un análisis descriptivo de la prevalencia de los tipos de demencia entre los pacientes valorados en nuestro centro y establecemos el grado de concordancia entre el diagnóstico clínico y el anatomopatológico. Los diagnósticos se establecieron en función de los criterios diagnósticos vigentes en cada momento.

ResultadosCiento catorce casos cumplieron los criterios de inclusión. Los diagnósticos más frecuentes tanto a nivel clínico como anatomopatológico fueron enfermedad de Alzheimer y demencia mixta, pero la prevalencia se invirtió pasando de un 39% y 18% a nivel clínico a un 22% y 34% a nivel anatomopatológico respectivamente. La concordancia entre el diagnóstico clínico y el anatomopatológico fue de un 62% (IC 95%: 53-72%).

ConclusionesCasi un tercio de nuestros pacientes no tenía un diagnóstico certero en vida, fundamentalmente a expensas del infradiagnóstico a nivel clínico de la enfermedad cerebrovascular.

Dementia has severe consequences for patients and families in particular, and for a country's healthcare system and economy in general.

Alzheimer disease (AD) has traditionally been considered the most frequent cause of dementia in Western countries. However, recent studies suggest that vascular dementia (VD), either isolated or in combination with AD, may be at least equally frequent.1,2

The diagnosis of dementia in daily practice is based on clinical findings and not on anatomical pathology (AP). Findings in AP are frequently more heterogeneous than might be expected. Almost 46% of the brains in a sample of subjects with a clinical diagnosis of AD displayed several pathological entities, although one clearly predominated.3

This article shows the distribution of types of dementia among patients from our clinic who agreed to donate neurological tissue. We also assess the concordance between clinical and AP diagnoses, and analyse the similarities and differences between our data and those reported in other studies.

Material and methodsStudy population and clinical evaluationWe analysed the brains of 114 patients from our clinic with a diagnosis of dementia or mild cognitive impairment (MCI). They or their families agreed to our request for tissue donation. We duly informed them about the procedure, its aim, and the possible implications, and they signed the applicable informed consent form.

We included the following variables in the database: sex; family history of dementia; age at symptom onset, diagnosis, and death; the baseline, final, and AP diagnoses; and complementary test results (neuropsychological examination [NPE], Mini-Examen Cognoscitivo4 [MEC], cranial computed tomography [CT], brain nuclear magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], single photon emission computed tomography, and electroencephalography).

We included the diagnosis made after the first examination at our clinic or at another centre as the baseline diagnosis; final diagnosis was established after our assessment and follow-up. Dementia was diagnosed according to DSM-IV5 criteria. To determine the type of dementia, we used the NINCDS-ADRA criteria for the diagnosis of possible and probable AD.6 NINDA criteria were also used for the diagnosis of VD and AD with VD. Other dementias were diagnosed according to the commonly-used criteria applicable at each time. Diagnosis of MCI was based on Petersen criteria.7

We established that there was concordance between clinical and AP diagnoses not only when both coincided, but also when, in the case that AP findings pointed to various pathologies, one clearly predominated over the others and clinical diagnosis was correct according to clinical data and the complementary tests available. Diagnoses were considered not to be concordant when final and AP diagnoses did not coincide, or when cerebrovascular comorbidity was not studied or considered in the final clinical diagnosis but was detected in the AP diagnosis.

Regarding MCI, we considered there to be concordance when AP findings were not decisive enough to meet the criteria for any type of dementia, so MCI was considered in the AP diagnosis of those cases.

Inclusion criteria were: diagnosis of dementia or MCI when the patient was alive, consent to tissue donation, no required judicial autopsy, and an available final AP report.

Tissue collection and processingThe neuropathological study protocol included basic techniques and specific procedures, according to the guidelines of the European network BrainNet.8

We included 114 brains: 5 cases were excluded, 3 due to lacking AP results and 2 because patients received no diagnosis of dementia or cognitive impairment when they were alive.

Statistical analysisWe performed a descriptive analysis to determine the mean age at disease onset, at diagnosis, and at the time of death; prevalence of sex; family history of dementia and diagnostic tests performed.

Furthermore, we analysed data on absolute and relative frequencies of every type of dementia at the time of baseline, final, and AP diagnoses.

We finally performed a point estimation and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) estimation of the concordance between clinical and AP diagnosis, as well as a multivariate analysis to determine which of the studied variables may have a role in increasing said concordance.

ResultsOne hundred and fourteen cases met the inclusion criteria. Mean age was 77±8 years at disease onset, 79±8 years at diagnosis, and 84±8 years at the time of death, with an average survival of 7 years. Seventy-five percent of patients were diagnosed within the 3 first years following symptom onset. Most patients were women (60.5%). Family history of dementia was detected in 30% of patients.

Complete NPE was available for 89.5% of the patients. Mean MEC score at diagnosis was 20±6 points. CT scans were available for 79% of patients, but MRI scans only in 19%. Single-photon emission CT and electroencephalography had been performed in 14% and 17% of patients, respectively. Seventy-five percent of patients had undergone a complete NPE and a neuroimaging study (CT or MRI) at the time of final diagnosis.

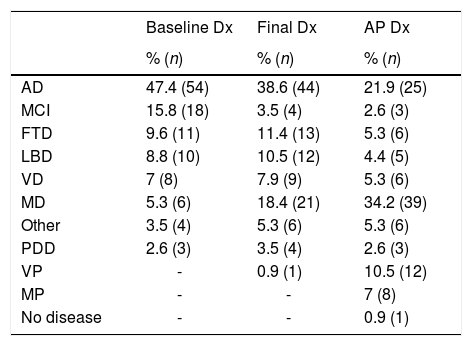

Table 1 includes prevalence by type of dementia at the time of baseline, final, and AP diagnosis. To simplify the analysis of results, it was decided that the category of frontotemporal dementia would include cases both of behavioural variant and of progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration. We used the term “vascular plus” (VP) to include the cases of cerebrovascular disease with non-AD neurodegenerative involvement, and the term “multiproteins” to refer to those cases with deposition of 2 or more proteins.

Diagnostic prevalence at baseline consultation (baseline Dx), at the time of death (final Dx), and at autopsy (AP Dx).

| Baseline Dx | Final Dx | AP Dx | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |

| AD | 47.4 (54) | 38.6 (44) | 21.9 (25) |

| MCI | 15.8 (18) | 3.5 (4) | 2.6 (3) |

| FTD | 9.6 (11) | 11.4 (13) | 5.3 (6) |

| LBD | 8.8 (10) | 10.5 (12) | 4.4 (5) |

| VD | 7 (8) | 7.9 (9) | 5.3 (6) |

| MD | 5.3 (6) | 18.4 (21) | 34.2 (39) |

| Other | 3.5 (4) | 5.3 (6) | 5.3 (6) |

| PDD | 2.6 (3) | 3.5 (4) | 2.6 (3) |

| VP | - | 0.9 (1) | 10.5 (12) |

| MP | - | - | 7 (8) |

| No disease | - | - | 0.9 (1) |

MCI: mild cognitive impairment; VD: vascular dementia; MD: mixed dementia; AD: Alzheimer disease; FTD: frontotemporal dementia; LBD: Lewy body dementia; PDD: Parkinson's disease dementia; VP: vascular plus; MP: multiproteins.

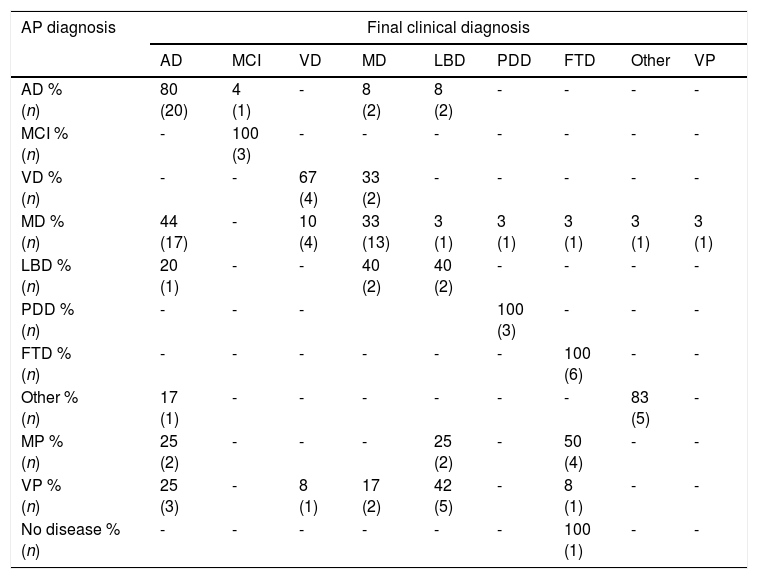

Concordance between final clinical diagnosis and AP diagnosis amounted to 62.3% (95% CI, 53%-72%). Table 2 details the data on diagnosis concordance for each type of dementia, while also attempting to identify the errors in clinical diagnosis, taking into account AP diagnosis.

Correspondence between anatomical pathology diagnosis and clinical diagnosis.

| AP diagnosis | Final clinical diagnosis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | MCI | VD | MD | LBD | PDD | FTD | Other | VP | |

| AD % (n) | 80 (20) | 4 (1) | - | 8 (2) | 8 (2) | - | - | - | - |

| MCI % (n) | - | 100 (3) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| VD % (n) | - | - | 67 (4) | 33 (2) | - | - | - | - | - |

| MD % (n) | 44 (17) | - | 10 (4) | 33 (13) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) |

| LBD % (n) | 20 (1) | - | - | 40 (2) | 40 (2) | - | - | - | - |

| PDD % (n) | - | - | - | 100 (3) | - | - | - | ||

| FTD % (n) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 100 (6) | - | - |

| Other % (n) | 17 (1) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 83 (5) | - |

| MP % (n) | 25 (2) | - | - | - | 25 (2) | - | 50 (4) | - | - |

| VP % (n) | 25 (3) | - | 8 (1) | 17 (2) | 42 (5) | - | 8 (1) | - | - |

| No disease % (n) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 100 (1) | - | - |

MCI: mild cognitive impairment; VD: vascular dementia; MD: mixed dementia; AD: Alzheimer disease; FTD: frontotemporal dementia; LBD: Lewy body dementia; PDD: Parkinson's disease dementia; VP: vascular plus; MP: multiproteins.

Availability of more complementary tests, the patient's sex, a lesser degree of cognitive impairment at diagnosis (based on the MEC score), and earlier diagnosis were not found to improve diagnostic concordance.

DiscussionWe found significant differences with regards to similar studies when we analysed AP prevalence of the different types of dementia.9 An interesting result was the higher prevalence of mixed dementia (MD) (34% vs 4%-21%) and the lower prevalence of AD in our study (22% vs 42%-65%).9 These differences may be exacerbated by the high mean age of our sample, which was associated with increased cerebral comorbidity.3

The main comorbidities we found were cerebrovascular diseases. In up to 53% of cases, the AP study confirmed the presence of vascular lesions, either in isolation or associated with the deposition of several proteins. Previous studies have found vascular lesions in 29%-41% of autopsy studies of patients with dementia.10

In 11% of the cases, deposition of Lewy bodies was found, whether in association with vascular lesions or with other proteins (cases included in the VP or MP categories, respectively). Furthermore, we observed deposition of at least 2 proteins (MP) in up to 7% of cases and 2 proteins and vascular lesions (included in the VP category) in 3%. Presence of Lewy bodies has previously been observed in 10%-20% of brains of patients with dementia.11

Advances in immunohistochemistry have enabled neurodegenerative diseases to be classified according to the deposition in the brain of a protein, which would be responsible for activating different pathogenic mechanisms and for differing symptoms. Nevertheless, both our study and previous studies have shown that the presence of an isolated type of lesion is an infrequent occurrence.11

The concordance we obtained was far from the 97% reported by other studies12; this value did not increase with more complementary tests, as observed in the multivariate analysis. The comparison was made between final clinical diagnosis and AP diagnosis. We did not analyse the reasons for differing baseline and final diagnoses, but progression of MCI to dementia and the possibility of sudden cerebrovascular events are well-known phenomena. Furthermore, the appearance of new symptoms or the performance of new complementary tests frequently lead to changes in diagnosis.

Our results are more in line with classic studies reporting that between 10% and 20% of patients clinically diagnosed with AD lack AP findings of the disease, and that up to 40% show AP findings of AD with no clinical diagnosis.13

The use of CT scans mainly for neuroimaging may have contributed to an underestimation of the cerebrovascular component.14 Other studies have revealed that having a structural neuroimaging study as part of the diagnostic process increased sensitivity and specificity for certain types of dementia.14

Our low levels of concordance may also be explained by the fact that donations of neurological tissue were frequently requested from patients with atypical clinical manifestations; also, this was a case series from clinical practice, where the examinations and assessments were frequently incomplete. Furthermore, we should note that our setting is a psychogeriatric clinic; therefore, our patients are very elderly and severe behavioural disorders constitute the most frequent reason for admission or consultation.

ConclusionNearly one third of our patients were not accurately diagnosed when alive, despite our efforts and experience, the use of clinical practice guidelines, and the complementary tests performed.

Although none of the drugs available have a significant impact on the course of the disease, we are convinced that correct therapeutic management of dementia helps slow disease progression. In addition to an improvement in patients’ quality of life, this has significant economic consequences.15

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors wish to thank all the staff of the Clínica Josefina Arregui for their commitment to excellence, and especially the patients and families for their trust in our clinic and their uninterested collaboration in this study.

Please cite this article as: Grandal Leiros B, Pérez Méndez LI, Zelaya Huerta MV, Moreno Eguinoa L, García-Bragado F, Tuñón Álvarez T, et al. Prevalencia y concordancia entre diagnóstico clínico y anatomopatológico de demencia en una clínica psicogeriátrica. Neurología. 2018;33:13–17.