Behçet disease (BD) is a multisystemic inflammatory disease of unknown aetiology characterised by aphthous ulcers in the mouth and genitals, ocular inflammation, skin lesions including erythema nodosum, and acneiform eruptions.1 Patients may also show neurological, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal involvement.2 Although BD has historically been considered more prevalent in men,3 recent studies point to a more balanced sex ratio.4 However, most patients with neurological involvement are men.5 BD affects young adults; age at onset is a predictive factor of clinical severity.6 Diagnosis is based on the presence of systemic and ocular clinical manifestations, since the disease has no pathognomonic signs. Ocular involvement in patients with BD usually includes bouts of inflammation occurring in the context of an underlying chronic retinal vascular inflammation. Bouts may affect the anterior pole, in the form of acute uveitis, or the posterior pole, with severe vitritis, retinal haemorrhages and exudates, cystoid macular oedema, or optic neuritis.7 BD may involve the nervous system in the form of recurrent meningoencephalitis typically affecting the brainstem, idiopathic intracranial hypertension (ICH) with or without sinus thrombosis, cranial mononeuropathies, cerebellar ataxia, myelitis, seizures, and even cognitive impairment.8 There are 2 clearly defined forms of BD: parenchymal and non-parenchymal. The most frequent manifestation of the latter is venous sinus thrombosis.9

We present the exceptional case of a patient diagnosed with neuro-Behçet disease (NBD) and rare attacks of ocular inflammation. He displayed bilateral optic atrophy secondary to chronic papilloedema in the context of ICH due to dural venous sinus thrombosis.

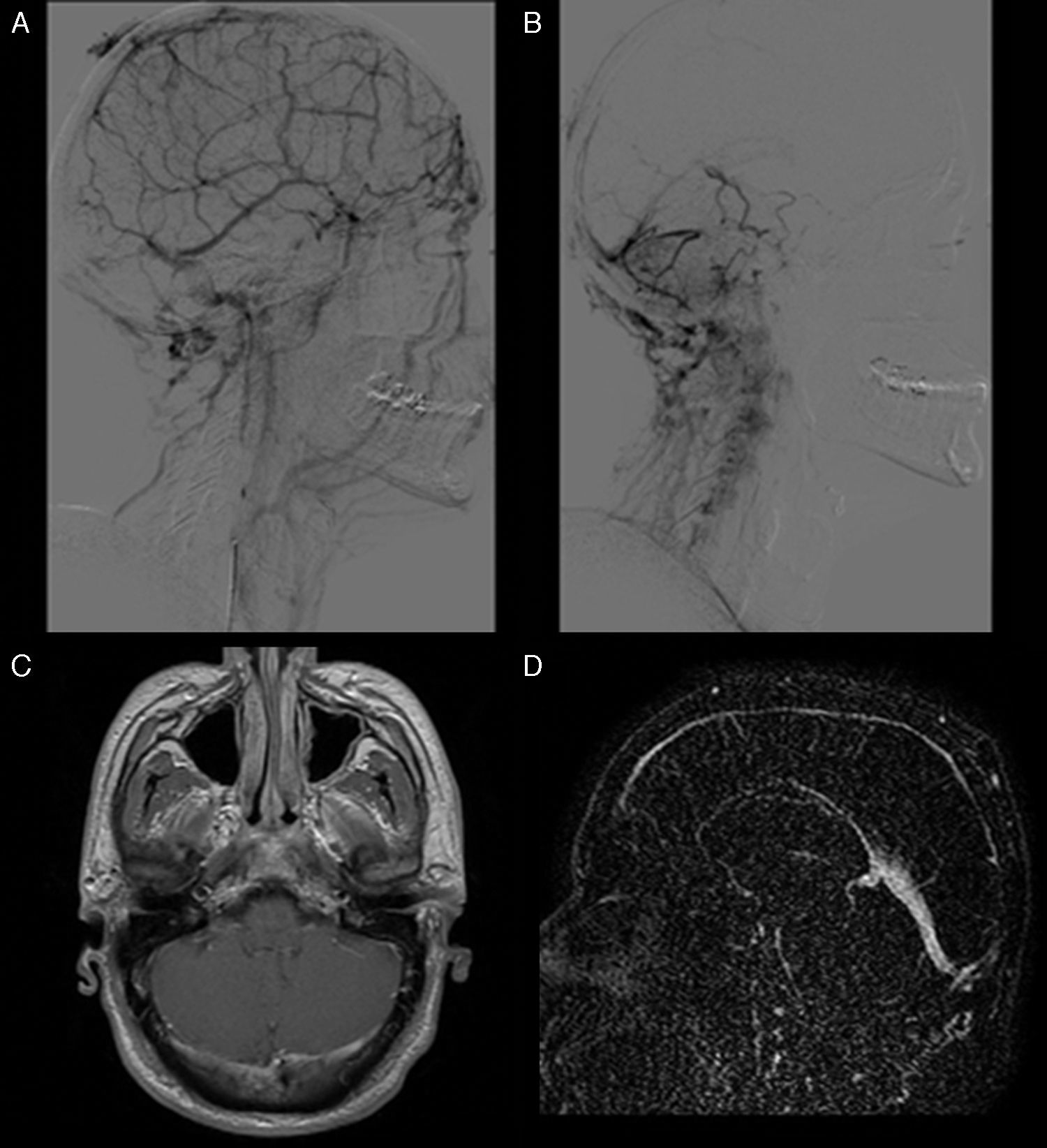

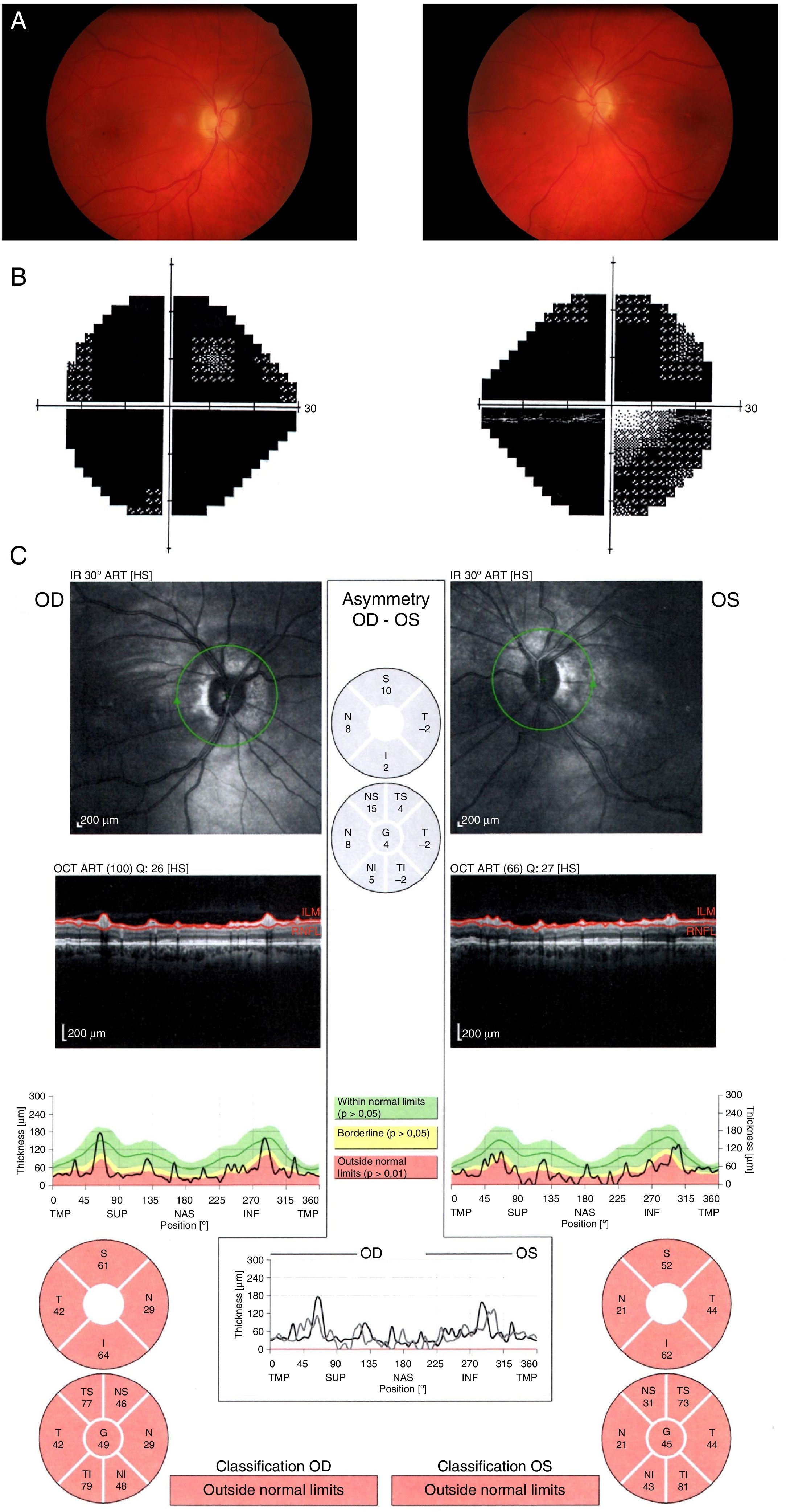

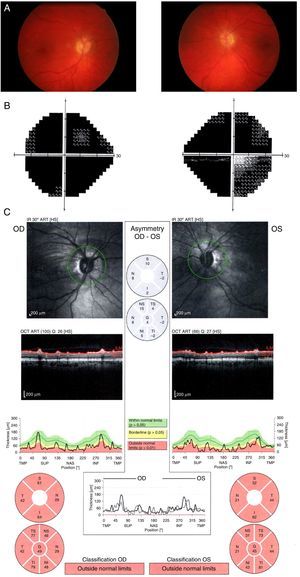

Our patient was a 37-year-old white man who was referred to our hospital's neuro-ophthalmology unit due to progressive and persistent vision loss in both eyes over the previous several months. He had been diagnosed with BD at the age of 18 based on the presence of recurrent mouth ulcers since adolescence, 2 bouts of bilateral anterior uveitis, and facial acneiform eruptions. At the age of 24, he was diagnosed with NBD due to thrombosis of the superior longitudinal, transverse, and sigmoid sinuses (Fig. 1) after consulting for symptoms of headache, intermittent vision loss, and papilloedema. He was treated with oral prednisone, azathioprine, colchicine, ciclosporin, and anticoagulants. In the years previous to our evaluation, our patient reported fluctuations in vision quality that were attributed to papilloedema secondary to ICH caused by dural venous sinus thrombosis. Two lumboperitoneal shunts to manage ICH achieved satisfactory results and decreased papilloedema and vision loss fluctuations. Mild papilloedema persisted one year later; doctors suggested a permanent lumboperitoneal shunt placement but the patient refused surgery. He had no other ophthalmological manifestations or relevant family history. At the time of his visit, he was taking oral acetazolamide, azathioprine, antiplatelet agents, and anticoagulant agents. The ophthalmological examination revealed a visual acuity of 0.1 in both eyes. Biomicroscopy showed pigmented keratic precipitates in both eyes and no active signs of ocular inflammation. Intraocular pressure and intrinsic and extrinsic ocular motility were all within normal limits. Eye fundus examination revealed bilateral papillary pallor and no signs of inflammation. The Humphrey visual field test (SITA-Standard 24-2 programme) revealed diffuse absolute scotoma in both eyes. Optical coherence tomography showed decreased thickness of the nerve fibre layer of both optic nerves (Fig. 2). Further analyses including a biochemical study, a total protein test, and measurements of folic acid and vitamins B1, B6, and B12 yielded normal results. An additional lumbar puncture disclosed an intracranial pressure of 15mmHg. CSF analysis revealed no abnormalities. Visual evoked potentials revealed no response on either side. An MRI scan showed no additional findings. Our patient was diagnosed with bilateral optic atrophy secondary to chronic papilloedema despite successful management of intracranial pressure.

Above: brain angiography. A) Supratentorial cortical venous flow is diverted to the facial and mastoid emissary veins due to chronic occlusion of the superior longitudinal sinus (note that it is irregular and not filled) and partial obliteration of venous flow from the transverse and sigmoid sinuses. These findings were linked to signs of thrombosis. B) Posterior fossa venous blood flow through the mastoid emissary veins. Below: MRI. C) Contrast T1-weighted MRI sequence showing irregular contrast uptake in the transverse sinuses. D) Post-contrast dynamic TRICK sequence acquired during venous phase showing threadlike uptake in the superior longitudinal sinus and marked congestion of the sinus rectus, linked to signs of chronic thrombosis.

Optic disc atrophy is an ophthalmological sequela that results in permanent interruption of axoplasmic transport in the optic nerve head. In the context of BD, it is usually unilateral or asymmetrical and occurs after repeated bouts of posterior uveitis (vitritis, vasculitis, neuroretinitis, optic neuritis). Early loss of visual acuity and neuroretinal rim pallor are essential clinical signs for distinguishing optic disc atrophy from glaucomatous optic neuropathy. As in our case, NBD may contribute to damaging the optic nerve in the form of either optic neuritis or papilloedema secondary to ICH.9,10 In these cases, involvement is usually bilateral and symmetrical. The most frequent cause of ICH in NBD is dural venous sinus thrombosis.10 Our patient had experienced only 2 episodes of uveitis previously, but ICH had been present for several years. Despite good management of intracranial pressure, ICH had caused papilloedema; although medical and surgical treatment had achieved partial resolution of papilloedema, it persisted over time, leading to atrophy of the optic nerve head.

Prevalence of NBD varies greatly among studies (5% to 49% of the cases). Parenchymal involvement includes a wide range of clinical findings compatible with sensory-motor ictal symptoms.11 Corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, colchicine, and biological products seem to provide good treatment options, although scientific evidence is insufficient to support using them.12 Non-parenchymal involvement is frequently associated with signs and symptoms of ICH and mainly caused by dural venous sinus thrombosis. These patients have a better prognosis than do those with parenchymal involvement, which suggests that these 2 forms possess different aetiopathogenic mechanisms.8 Recent studies have shown that anticoagulant treatment is decisive for improving prognosis.13 Refractory patients and those with precisely located thrombi may benefit from mechanical thrombectomy with or without thrombolytic treatment.14

ConclusionPapilloedema secondary to ICH is a rare finding in patients with NBD. Prognosis is usually favourable, although the condition may cause optic atrophy and even vision loss regardless of the level of previous ocular inflammation.

FundingThis study has received no public or private funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors would like to publicly thank neuroradiologist Santiago Darío Rosati for his assistance in selecting and commenting on the brain MR and angiography images published in this article.

Please cite this article as: Pérez-Bartolomé F, Sanz-Pozo C, Darío Rosati S, Santos-Bueso E, Porta-Etessam J. Pérdida visual debido a trombosis de senos venosos en neuro-Behçet. Neurología. 2017;32:413–416.