Aortic dissection occurs when the layers of the aortic wall separate as the result of an entrance of blood through a tear in the intima. The mean frequency reported for primary dissection of the abdominal aorta is less than 2%, compared with the ascending aorta (70%), the descending aorta (20%), and the aortic arch (7%).

Clinical caseA 74-year-old man begins his illness with sudden and intense lumbar and abdominal pain. An angiotomography showed an infrarenal abdominal aortic dissection extending to both primitive iliac arteries just before their bifurcation. An aortobifemoral bypass was performed with a bifurcated Dacron graft with a good postoperative result.

ConclusionPrimary abdominal aortic dissection is a rare pathology that in symptomatic patients can be treated with an open or endovascular repair. If the open technique is decided on, excision plus an aortobifemoral bypass can be carried out with good results as in this case.

Aortic dissection occurs when the layers of the aortic wall separate as the result of an entrance of blood through a tear in the intima. This catastrophic process sometimes involves the thoracic aorta; thus, a limited dissection of the abdominal aorta is rare.1 The mean frequency reported for primary dissection of the abdominal aorta is less than 2%, compared with that of the ascending aorta (70%), the descending aorta (20%), and the aortic arch (7%).2 Causes of dissection may be spontaneous, traumatic or iatrogenic. Its clinical presentation may be either acute with a sudden onset of the symptoms, or chronic (over 14 days). Natural history and treatment options are not well established; its description in the literature is mainly based on case reports and series with a few cases. Strategies for its treatment are conservative for asymptomatic cases with a non-dilated aorta, and for symptomatic patients, repair through the placement of a stent. The latter is the technique of choice for open surgery.3 Hereunder we report a case of primary dissection of the abdominal aorta, its clinical presentation and a review of the literature about this pathology.

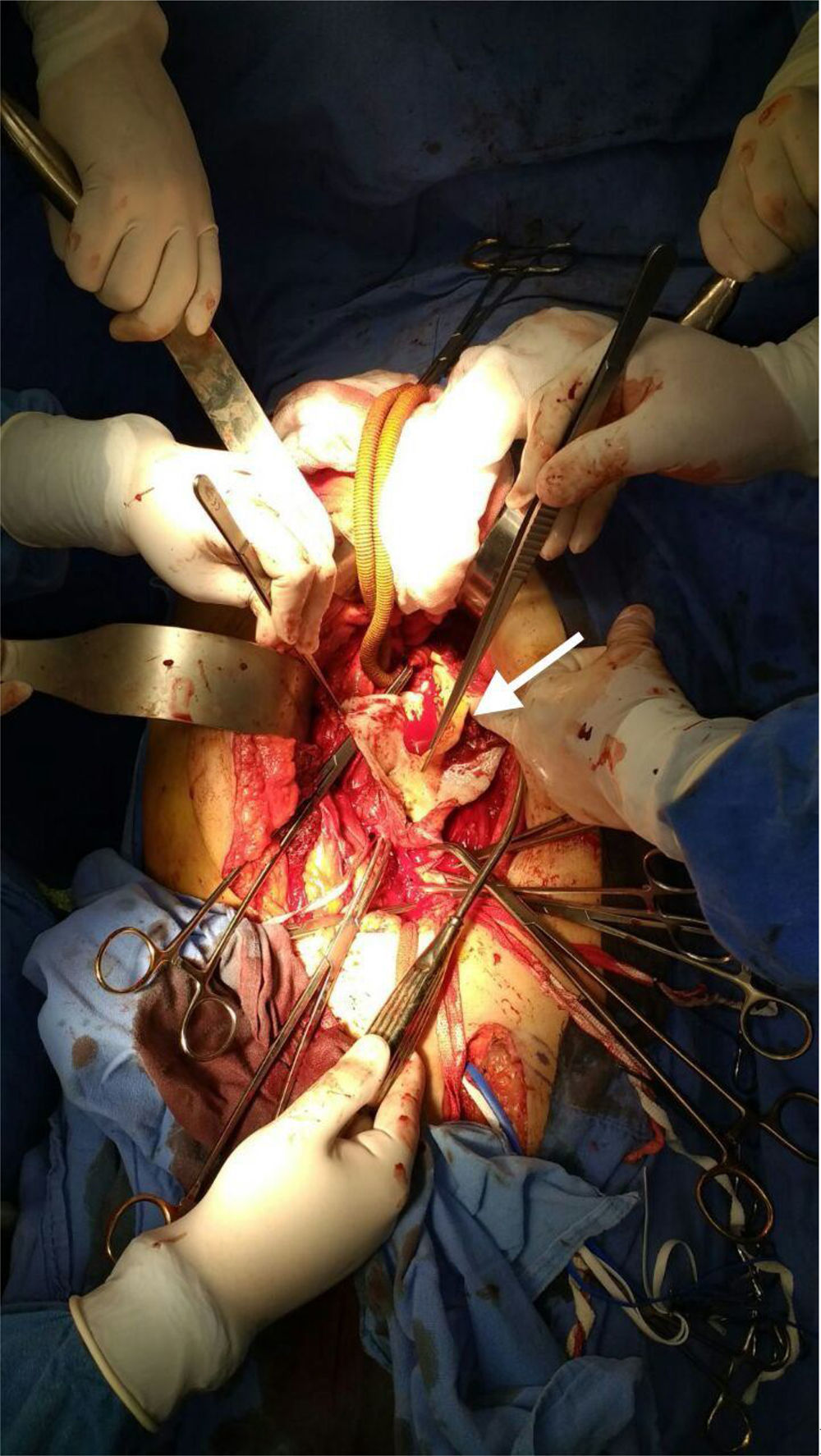

Clinical caseA 74-year-old man with a history of systemic high blood pressure and benign prostatic hyperplasia in treatment begins his illness 24h prior to his hospital admission with sudden and intense lumbar and abdominal pain. Hence, he attends a private clinic where he gets an abdominal CT scan showing a dilation of the infrarenal abdominal aorta. Therefore he is taken to a public third level hospital in order to continue tests. At the moment of admittance, his vital signs were: blood pressure 130/80mmHg, heart rate of 92, respiratory rate of 12, body temperature of 36.6°C. During physical examination, the abdomen was tender and depressible, painless to palpation, with a pulsatile mass of about 5cm, poorly defined, with a negative deBakey maneuver and with no data of acute abdomen. Lower limbs were euthermic, with preserved mobility and sensitivity, with distal arterial integrity, with biphasic flows audible with a Doppler probe, with a capillary refill of 2–3s, without any data of hypoperfusion. Lab work data reported hemoglobin 13.3g/dL, hematocrit 43%, leukocytes 7100/mm3, glucose 100mg/dL, urea nitrogen 16mg/dL, creatinine 0.9mg/dL, phosphokinase creatine 63UI/L, and MB fraction of phosphokinase creatine 9UI/L. The patient underwent a thoracoabdominal angiography of the iliac vessels, where an infrarenal abdominal aortic dissection is evident, going from the intimal flap and extending to both primitive iliac arteries just before their bifurcation. Also an aortic dilation of up to 56mm at an infrarenal level with the output of the inferior mesenteric artery of true vessel lumen (Figs. 1 and 2). Given the angiographic findings and the patient's clinical picture, he is admittedto complete pre-surgical protocol and definitive therapeutic planning.

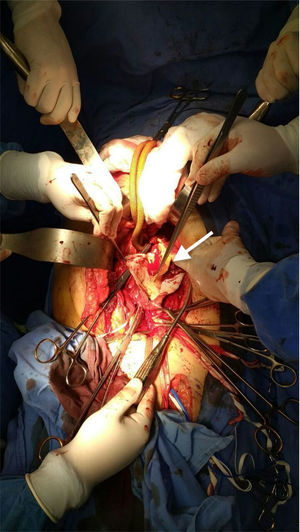

An aortobifemoral bypass with a bifurcated Dacron graft was performed. As a transoperative finding, we discovered an infrarenal aortic dilation of 5.5cm with an extension of the dissection from 1cm under the left renal artery up to just before the bifurcation of both primitive iliac arteries (Fig. 3). The dissection flap involved the left hypogastric artery to 1cm after its emergence, both ectatic common iliac arteries and thin walls without atherosclerotic plaque. The surgery was performed without complications. After surgery, the patient was taken to the postsurgical care unit for monitoring and, 72h later, was transferred to a room where he was monitored for 48h. An ankle-brachial index test was conducted, the results of which were 0.9 on the right side and 1.0 on the left side, proving that there was a good distal arterial perfusion. Moreover, in the control lab work, results did not show elevation of urea nitrogen, hepatic enzymes or lactate. Hence we considered a proper visceral perfusion. With clinical improvement and a positive evolution, the patient was sent home.

DiscussionThere are less than 100 reported cases of primary aortic dissection in the literature.4 In less than half of the cases, dissection extends to the common iliac artery, and in rare cases, it extends to the visceral arteries. Over a third of primary abdominal aorta dissections are accompanied by abdominal aortic aneurysms. Between 51% and 78% of patients have systemic arterial hypertension, and most present acute abdominal aortic symptoms. These symptoms include abdominal pain (47%), lumbar pain (23%), claudication or critical ischemia of lower limbs (17%), paraplegia (3%) and are asymptomatic in only 17%.5

Graham et al. found that 70% of these dissections are spontaneous, followed by trauma and iatrogenic causes, each one with a 15% rate of occurrence. The real prevalence of this pathology is unknown due to the fact that many patients are asymptomatic. Most of the time, it is diagnosed using a CT scan or an MRI, and it is commonly associated with the presence of an aortic aneurysm, aortic ulcer or intramural hematoma. Most of these dissections occur in the infrarenal aorta, with damage to the ilio-femoral axis.

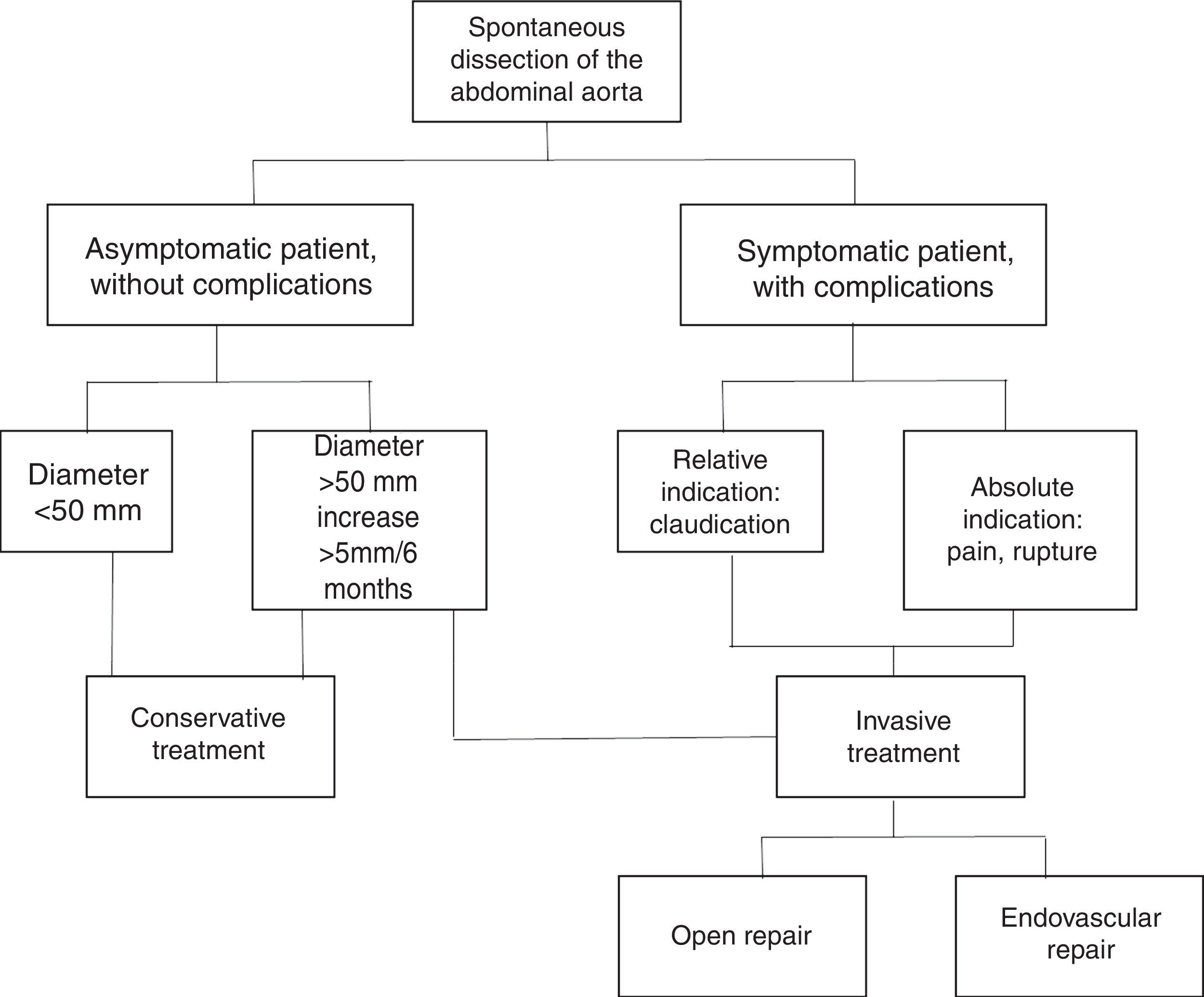

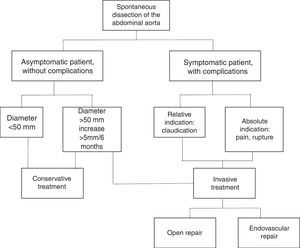

Abdominal aorta dissection management remains a topic of discussion; a review of the literature over the last 50 years, mostly in case reports, results in a treatment algorithm for this vascular pathology6 (Figure 4).

Algorithm for the treatment of spontaneous dissection of the abdominal aorta.

The treatment of choice is endovascular repair; however, due to the lack of material and after assessing the case, the patient was considered as a candidate for open surgical treatment.

Mozes et al. reviewed 41studies done in Great Britain and reported that 14% of patients with a primary dissection of the abdominal aorta presented aortic rupture. They recommended elective repair considering the high mortality rate in case of rupture. Moreover, Jonker et al. in a meta-analysis of 92 patients, including 73 patients with primary dissection of the abdominal aorta, reported an incidence of aortic rupture of 10%, and a higher mortality rate, as well as complications, in patients who received conservative treatment versus patients who underwent open endovascular repair.7 A recently published series found endovascular intervention success rate to be very high (100%). Nevertheless, being high-risk patients within this series, 14% died due to heart complications. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissections suggests that patients with an acute dissection treated with a surgical intervention have a better result compared to those treated only with medical therapy.8

An aortic rupture has a mortality rate of up to 90%, and this occurs in 10% of patients with abdominal aortic dissection. Therefore, these patients ought to be under tight supervision in order to detect morphological changes in the dissection. Indications for an intervention include non-improving symptoms, a rapid expansion of the aneurysm and morphological changes in the dissection.9

ConclusionPrimary abdominal aortic dissection is a rare pathology which may clinically occur in many different forms,10 among some of the main symptoms are abdominal or unspecified lumbar pain and data of critical ischemia of the lower limbs. A significant percentage of said patients may be asymptomatic, since the clinical picture may be chronic and only progress slowly, and dissection is a radiological finding during studies of other pathologies of a non-vascular origin. Patients who are treated surgically or with endovascular procedures have a lower mortality rate versus patients who are treated conservatively, having as a leading cause of said intervention the presence of lower limb hypoperfusion data, aortic dilation progression or rupture of the aneurysmal sac. Even though endovascular therapy is currently considered the gold standard in abdominal aortic dissection treatment, there is the option of open surgery when, for any given reason, there is no possibility to perform an endovascular intervention, with positive results when managed by expert personnel.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.