Intangible resources are widely considered the main source of gaining competitive advantage and sustain superior performance in transition and emerging economies such as China, particularly in SMEs sector. In this paper, we argue theoretically (under resource-based view RBV) and demonstrate empirically that intangible resources (e.g. dynamic managerial capabilities (DMC) and dominant logic (DL)) are indispensable for long-term superior firm performance. We calculate CFA to test the measurement model. With an empirical study of 328 SMEs in China, the results indicate that highly competitive environment facilitates the impact of dominant logic on firm performance. Furthermore, our results also support that there is a significant mediating role of dominant logic between dynamic managerial capabilities and firm performance. In the end, we discussed managerial implications and theoretical contributions.

Dynamic managerial capabilities are valuable intangible resources that enable firms to sustain superior performance over time in the dynamic environment (Wilden, Gudergan, Nielsen, & Lings, 2013; Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009; Li & Liu, 2014). Prahalad and Bettis (1986) argued that organizations can achieve a high level of performance if they have the ability to ‘respond fast’ to the rapidly changing environment and competitors’ moves. Organizations can hardly be successful if they fail to utilize available resources and managerial capabilities to the fullest. The main objective of this research is to investigate the important role of intangible resources in SMEs performance in a transition economy. The motivation behind choosing this research topic is the important role of dynamic managerial capabilities and dominant logic in firms’ performance in highly competitive transition economies such as China. In highly volatile business environments in transition economies where product and business model life cycles are shortened (Stewart & Hamel, 2000), firms need to constantly search for new opportunities and such kind of characteristics can lead firms to improved performance (Prahalad & Krishnan, 2008). Executive level managers play a key role, as the success or failure (i.e. performance) of the organization highly depends on how these managers respond and adapt to the volatile environmental conditions (i.e. to the opportunities and threats) through building, integrating and reconfiguration of organizations resources or simply we can call these as dynamic managerial capabilities (Prahalad, 2004; Teece, 2007).

Adner and Helfat (2003: 1012) define dynamic managerial capabilities as ‘the capabilities with which managers build, integrate, and reconfigure organizational resources and competencies’. Managerial decisions have a profound effect on firm performance, under uncertain market conditions managers must think different regarding the correct course of actions, dynamic managerial capabilities help managers take correct decision and design corporate strategy (Adner & Helfat, 2003). Dominant logic is the second intangible resource discussed in this research. Managers’ dominant logic refers to ‘the way in which managers conceptualize the business and make critical resource allocation decisions—be it in technologies, product development, distribution, advertising, or in human, resource management (Prahalad & Bettis, 1986). Bettis and Prahalad (1995) and Kor and Mesko (2013) discussed how dynamic managerial capabilities of executive level team shape and change dominant logic as changes occur in the highly volatile market to make critical resource allocation decisions in order to achieve superior performance. Research studies e.g. Obloj, Obloy, and Pratt (2010) identified that a firms’ dominant logic with external orientation, pro-activeness, and simple routines significantly influences the performance of the firms in a transition economy. Dominant logic and dynamic managerial capabilities serve as key intangible resources of the firms in emerging/transition economies characterized by resource shortages. Dominant logic provides real and meaningful insight into why companies exist and what leads to differential performance. Companies can win the competition battle when they create customer value better than the competition and will lead them to superior performance (Fawcett & Waller, 2012).

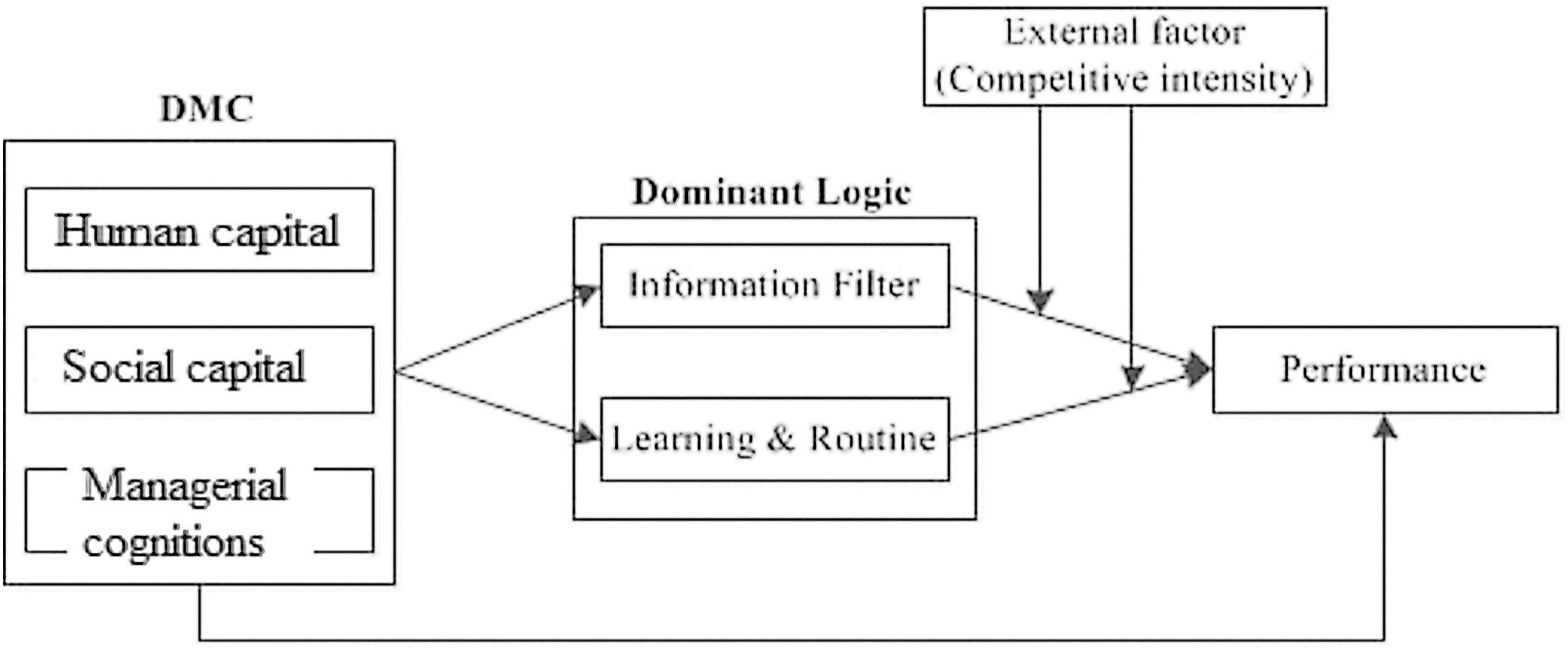

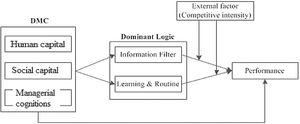

Previous research has different gaps many research studies applied contingent approach such as strategy, nature of firms or industry characteristics to see the positive, negative or curvilinear relationship of dynamic managerial capabilities, dominant logic, and performance and give inconsistent research findings. In this paper, we combine all these contingent approaches to check their relationship. The problem attributed is the lack of research on linking the impact of dynamic managerial capabilities on firm performance and how this relationship is influenced by dominant logic (mediating effect) and competitive intensity (moderating effect). The existing research only discussed and highlighted the relationship between dynamic managerial view, dominant logic, and firm performance and not more than few researchers have addressed how to achieve this performance. To fill this research gap the present paper develops a theoretical framework based on RBV, dominant logic and organizational theory and discusses the largely ignored link and tries to fill the gap among earlier works done by various researchers regarding factors affecting firm performance i.e. DMC (Human capital HC, social capital SC and managerial cognition MC), external factors (competitive intensity), and see the mediating role of DL. Despite the importance of intangible resources, there has been a less empirical investigation on the relationship between a firm's dynamic managerial capabilities, dominant logic, and the firm performance, the main objective of this paper is to contribute and discuss this missing link largely ignored in the literature. The contributions of the paper include addressing questions such as how dynamic managerial capabilities of the firm change and shape dominant logic that influence firm performance? it also addresses how dominant logic effect firm's performance and how dynamic managerial capabilities evolve and change in response to changes in the environment? This paper also develops and tests the moderating effect of external factors (competitive intensity) on how dominant logic influence firm performance. In our research model, we see the mediating effect of dominant logic on dynamic managerial capabilities and performance as changes in dominant logics also influence dynamic managerial capabilities while scanning the internal or external environment for changes which subsequently effect firm's performance. Today every organization in hyper-competitive and innovative environment faces the main challenge of how to achieve and sustain competitive advantage and long-term performance (Finster & Hernke, 2014). Our endeavor in this regard include minimizing this challenge while adding to the existing incomplete research and linking dynamic managerial capabilities (HC, SC and MC) (Kor & Mesko, 2013; Eggers & Kaplan, 2013) to dominant logic (Obloj et al., 2010) and how these factors affect organizations’ performance especially in emerging economies like China. Summing up we can say that the main contribution of this paper is that it adds to the theory that dominant logic, dynamic managerial capabilities are intangible resources (RBV) and play an important role in SMEs performance in transition economies such as China.

The remainder of this paper has the following organization. “Theoretical background and hypothesis development” section presents theoretical background and develops related hypotheses. “Methodology” section then outlines the study methodology, and “Empirical results” section discusses the empirical results. Finally, “Discussion and conclusion” section includes conclusions and managerial implications and limitations of the study along with future research directions.

Theoretical background and hypothesis developmentThe resource-based view (RBV) of the firm seeks to explain the sources of long-term organizational success; scholars e.g. Barney (1991) and Peteraf (1993) explained the cornerstone of competitive advantage through RBV. The role of managers in understanding and describing key resource endowments held and controlled by firms is crucial in order to achieve superior performance and sustained competitive advantage (JBarney, 1991). Under RBV assumption firms are basically heterogeneous in terms of resources and capabilities; the RBV posits that long-term financial success depends on how these firms most efficiently and effectively develop and utilize resource endowments in the marketplace (Peteraf, 1993). Such resources can either be tangible or intangible in nature (Barney, 1991) and can have varied sources of origin (Hooley, Broderick, & Möller, 1998). A resource to contribute to the creation of a sustainable competitive advantage, however, it must be valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (Barney, 1991; Line & Runyan, 2014). Dynamic capabilities and dominant logic of the firm are intangible and valuable resources of the firm and can explain firm competitiveness more effectively than other resources (Zahra, Sapienza, & Davidsson, 2006).

Dynamic managerial capabilities enable business enterprises to create, allocate, and protect the intangible assets that support superior long-run business performance (Helfat & Peteraf, 2009). Managers while utilizing their managerial capabilities scan external environment (external orientation) to identify new threats and opportunities and integrate new ideas and knowledge with existing capabilities to be successful in product and market development (Helfat & Raubitschek, 2000). The resource-based view (Peteraf, 1993; Wernerfelt, 1995) and knowledge management approaches (Grant, 1996) suggested that capabilities and knowledge form the basis for differential firm performance. Creating new competitive advantages are highly desirable and dynamic managerial capabilities make things happen, especially the top-level managers and their contribution in dominant logic both managerial and organizational as a whole. The concept of dynamic managerial capabilities (Helfat & Peteraf, 2009; Li & Liu, 2014) has attracted increasing attention.

Dynamic managerial capabilities and dominant logicBy definition, dynamic capabilities involve adaptation and change, because these capabilities can be regarded as a transformer for converting resources into improved performance while creating competitive advantage. Most of the studies also advanced the notion that firms compete with one another based on their ability to learn (learning orientation-dominant logic) and apply knowledge to foreign and domestic markets (Prange & Verdier, 2011) i.e. on the basis of their dynamic managerial capabilities, in particular, the top management (Zahra et al., 2006).

Different authors have insightfully identified the three attributes underpinning DMC that are managerial human capital, managerial social capital and managerial cognitions (Adner & Helfat, 2003). Managerial human capital comprised of skills, the stock of knowledge, education, and experiences, which can be developed over time (Florin, Lubatkin, & Schulze, 2003; Becker, 1993). Many studies addressed the importance of human capital in enabling firms to adapt successfully to changes in technology and markets. This change in technology and markets create opportunities and threats to which managers respond based on their experiences, knowledge, and skills (Taheri & van Geenhuizen, 2011). This proactive approach of managers helps them acquire new experience, skills, and knowledge (Nour, 2013). Managerial social capital and dominant logic are intertwined such as managers through external orientation scan the environment for information while looking into external environment and utilize their social connections and networks of relationships that include family, friends and casual relationships as suppliers of important resources of knowledge, information and support (Felício, Couto, & Caiado, 2012) based on these information firms perceive their environment either in terms of opportunities or threats. In such kind of situations, managers behave proactively and often make decisions based on advice from friends, colleagues and other acquaintances, which is especially relevant for small businesses (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998).

As stated in behavioral organization theory, cognitions act as a filter between the managers’ understanding of the inter-organizational environments and the intra-organizational context (March, Simon, & Guetzkow, 1963). Researchers (Boisot & Li, 2005; Gavetti, Levinthal, & Rivkin, 2005) argued that the information filter, the second stream of dominant logic focuses more on the content of managerial cognitions and mind-sets. Bettis and Prahalad (1995) treat dominant logic as a knowledge structure that evolves over a substantial period of time as a result of experiences with the core businesses, tasks critical to success, performance measures, and values and norms evolution. This knowledge structure works as a set of perceptual and conceptual filters that “sifts” and transform information from the environment into firms for strategic decision-making (von Krogh, Erat, & Macus, 2000). Based on above discussion we can posit that,

H1a. DMC has a direct and positive effect on information filter (pro-activeness and external orientation) of a managerial team of the firm.

Managers learn from their own experiences and from others. Managerial human capital contributes in shaping managerial learning and routines i.e. the second stream of dominant logic, in a sense that manager's previous experiences and specialized knowledge regarding strategic decisions and resource allocations, combinations and acquisitions and all related skills assist managers schemas (cognitions) that managers use to perceive, interpret and evaluate a particular environment (internal and external), as a result this process yields strategic choices and priorities for the firms growth and competitive positioning. In emerging economies, firms transform learning (Van de Ven & Poole, 1995) into actions (routines) with a proactive orientation to the environment better perform than those firms reacting to the threats (Lyles & Salk, 2007). Organizations with less standardization and formalizations can better transform learning into routines through their human and social capital lead to superior performance (Obloj et al., 2010). Human capital is a set of characteristics that provide individuals with more skills, namely, cognition, experience and knowledge, organizations are better able, using human capital, to adapt continuously to changing circumstances in the external environment, to perceive new opportunities and threats, and to gain competitive edge (Becker, 1993). Managers, in order to gain access to skills and knowledge, use their social connections and networks in a variety of ways. These strong social bonds help SMEs shape general attitudes toward innovation and market change and enhance organizations capacity to survive external shocks (changes) or adapt to sudden changes in the external environment (Field & Spence, 2000). Following (Porac, Ventresca, & Mishina, 2002) we can identify four conceptual levels of managerial cognition related to the material aspects of the business model of the organizations: industry recipe, reputational rankings, boundary beliefs, and product ontologies. These managerial beliefs or cognitions are related to the logic of the economic, competitive and institutional environment and their effects on the focal organization (Spender, 1989). In the information-rich competitive environment, many organizations find it hard to change but Prahalad suggested that the dominant logic serves as an information filter helps the firms to focus on relevant data that assist managers in strategy development with the help of dynamic managerial capabilities. Firms learn through managerial actions (successes and failures), from internal and external environment which as a result transform and becomes codified in firms via rules and routines (Miller, 1996)

Thus we can argue that,

H1b. DMC has a positive relation with flexible routines and learning orientation of the firm.

Dynamic managerial capabilities and SMEs performancePast literature shows that firms benefit from having dynamic managerial capabilities in crafting new business and corporate strategies, entering new market arenas, completing successful mergers; learning new skills, overcoming inertia, increase their other resources, introducing innovative programs that stimulate strategic change, and successfully commercializing new technologies generated within their R&D units, these activities increase organizational agility, market responsiveness and superior performance (Bowman & Ambrosini, 2003; Marsh & Stock, 2003). The three elements and attributes of dynamic managerial capabilities i.e. human capital social capital and managerial cognitions positively influence SMEs performance. Dynamic managerial capabilities positively influence firm performance in several ways (Protogerou, Caloghirou, & Lioukas, 2012); such as they match the resource base of the firm with changing environments in which the firm competes (Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997); create market change in terms of opportunities (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000); they support both the resource-picking capability and building rent-generating mechanisms; and improve inter-firm performance for details see (Gudergan, Devinney, Richter, & Ellis, 2012). Dynamic managerial capabilities improve the effectiveness, efficiency, and speed of firm's responses to environmental changes (Hitt, Bierman, Shimizu, & Kochhar, 2001) which ultimately improve performance. They allow and enable the firm to exploit any opportunity that can enhance revenue and adjust its operations to reduce costs (Drnevich & Kriauciunas, 2011). Therefore we can posit that,

H1c. Dynamic managerial capabilities positively influence SMEs performance.

Dominant logic and SMEs performanceFawcett and Waller (2012) summarized and argued that dominant logic can provide real and meaningful insight into why companies exist and what leads to differential performance. Prahalad and Bettis (1986) stated that dominant logic is the process and the way in which managers conceptualize the business and make critical resource allocation decisions. Prahalad and Bettis (1986) argued that firms can achieve a high level of performance if they have the ability to ‘respond fast’ to the rapidly changing environment and competitors moves. Prahalad (2010) warned, “Companies should stop looking at threats and opportunities through the lens of the dominant logic. Instead, the moment they spot signs of change, executives must decide what they can preserve—and what they must discard—in the dominant logic as they prepare to transform the organization” (p. 36). Firms are dependent upon their environment and Smith and Cao (2007) argued that choices and actions can be undertaken, not only as a direct response to environmental pressures, but also, more proactively, as a part of the search, exploration, and opportunity. Pro-activeness or proactivity is an attribute of the strategic orientation of the company reflecting an opportunity-seeking feature of a firm implying that firms anticipate acting ahead of future demands by taking full advantage (exploration and exploitation) of fleeting opportunities in the market (Lumpkin & Dess, 2001; Talke & Hultink, 2010).

Many authors for example Talke (2007) suggested that proactive orientation helps firms with opportunity seeking, the anticipation of future demand but also enable to exploit emerging opportunities. In transition economies resources are limited; SMEs through proactive behavior can discover, evaluate and acquire such scarce resources. This proactive approach of firms not only leads to more experimentation that forms effective and expert cognitive maps of the firms but also helps firms to enact to their environment (Dane & Pratt, 2007). Therefore we can predict the following:

H2a. SMEs high level of pro-activeness (information filter) positively influences SMEs superior performance.

Firms learn from experimentations and transform knowledge and experience into actions is important to perform better in emerging economies like China (Lyles & Salk, 1996). Firms’ ability to learn from their business failures is important. Many research studies stressed the importance of organizational learning from their experiences (dramatic failures). Organizations better able to learn from their failures become expert with their complex strategic orientations and more effective actions (Dane & Pratt, 2007). This learning orientation (from failures) helps managers transform their learning into SMEs via structural or procedural changes that assist managers’ effective decision-making. Firms through learning develop routines and standard procedures. These routines help firms’ allocations of physical and non-physical resources, formulating and execution of business strategies and setting and monitoring of performance targets (Grant, 1988). Over time organizational learning transformed into well-structured actions with well-developed dynamic or flexible routines appropriate for internal and external contingencies lead to firms superior performance. In emerging economies, successful organizations need to create flexible routines where formalization and standardization are limited (Obloj et al., 2010). Based on above discussion, we propose that:

H2b. SMEs learning orientation and low level of routines will lead to superior firm performance.

Dynamic managerial capabilities and firm performance; a mediation modelThe resource-based view (Peteraf, 1993; Wernerfelt, 1995) and knowledge management approach Grant (1996) suggest that managerial capabilities and knowledge form the basis for differential firm performance. Many research studies e.g. Brush, Greene, and Hart (2001) and Shane and Venkataraman (2000) mentioned that because of their higher levels of self-confidence and decreased concerns over risk individuals with higher levels of human capital have a higher tendency for entrepreneurial activity. It refers to those individuals possessing greater levels of knowledge, skills, and abilities acquired through education, training, and experience called human capital (Becker, 1993). Another element of dynamic managerial capabilities i.e. social capital focuses on the fitness of the players and their personal relationships (Lin & Wu, 2014). Social capital includes networks of relationships and assets located in these networks (Coleman, 1988) and it has been found that social capital positively influences firm performance (Baker, 1990), organization resource exchange and product innovation. Coleman (1988) argued that social capital serves as a facilitator of social structure for certain actions of individuals, which benefit both the individuals and the firms and that lead to varieties of firm performance (Batjargal, 2003).

DMC positively influence firm performance in several ways; for example they match the resource base of the organization with changing environments in which the firms compete (Teece et al., 1997); create market change in terms of opportunities (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000); support both the resource-picking and capability-building rent-generating mechanisms; and improve inter-firm performance (for details see Gudergan et al., 2012). Here a question arises of how all these can happen? We try in this paper to answer this question while empirically testing that dominant logic helps SMEs achieve superior performance through managerial capabilities. Fawcett and Waller (2012) summarized and argued that dominant logic can provide real and meaningful insight into why companies exist and what leads to differential performance. Dynamic capabilities, through scanning opportunities and reconfiguration, provide the organization with a new set of decision options, which have the potential to increase firm performance (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Teece, 2007). Firms are highly dependent upon their environment and Smith and Cao (2007) stated that choices and actions can be undertaken, not only as a direct response to environmental pressures but also, more proactively, as a part of the search and exploration. Talke (2007) suggested that proactive orientation of managerial team helps firms with opportunity seeking, the anticipation of future demand as well as enable to exploit emerging opportunities. Transition economies are characterized by scarce resources; firms through proactive behavior can discover, evaluate and acquire such scarce resources. This proactive approach of firms not only leads to more experimentations that form effective and expert cognitive maps (i.e. managerial cognitions) of the organizations but also helps organizations to enact to their environment (Dane & Pratt, 2007). Firms learn from these experimentations and transform knowledge and experience into actions (information filter) is important to perform better in emerging economies like China (Lyles & Salk, 1996). We posit the following,

H3a. The effect of DMC on firm performance improves with the external and proactive orientation of SMEs.

Past literature shows that firms benefit from having dynamic managerial capabilities in crafting new business and corporate strategies, entering new market arenas, learning new skills, overcoming inertia, increase their other resources, introducing innovative programs that stimulate strategic change, and successfully commercializing new technologies generated within their R&D units, these activities increase firms agility and market responsiveness and superior performance (Bowman & Ambrosini, 2003; Marsh & Stock, 2003). Organizations better able to learn from their failures become expert with their complex strategic orientations and more effective actions (Dane & Pratt, 2007). This learning orientation from failures helps managers transform their learning into organizations via structural or procedural changes that assist managers’ effective decision making. Firms through learning develop routines and standard procedures. These routines help organizations allocations of physical and non-physical resources, formulating and execution of business strategies and setting and monitoring of performance targets (Grant, 1988). DMC improve the effectiveness, efficiency, and speed of organizational responses to environmental changes (Hitt et al., 2001) which ultimately improve firm performance. They allow and enable “the firm to exploit any opportunity that can enhance revenue and adjust its operations to reduce costs (Drnevich & Kriauciunas, 2011). Dynamic capabilities, through scanning opportunities and reconfiguration, provide the organization with a new set of decision options, which have the potential to increase firm performance (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). Therefore, we can hypothesize the following:

H3b. The effect of DMC on firm performance improves with learning and simple routines of the firm.

The moderating role of competitive intensityFirms compete in highly volatile business environments characterized by global competition. This environmental dynamic and volatile conditions influence the effect of dominant logic and managerial capabilities on firm performance, in particular, the competition. In his research study (Prahalad & Bettis, 1986) summarized “that industry structure in which the firm competes and competitive position of the firm's businesses within these industries is the key determinants of performance”. Competitive intensity is an important factor contributing to the environment hostility (Zahra & Covin, 1995). Firm's external orientation and behavior are heavily influenced by the actions and contingencies undertaken by the competitors, with increased uncertainty and less predictability (Auh & Menguc, 2005). Zahra (1993, p. 324) stated: When rivalry is fierce, companies must innovate in both products and processes, explore new markets, find novel ways to compete and examine how they will differentiate themselves from competitors. To this end, Auh and Menguc (2005) have discussed how firms can respond to counter competitors’ behaviors in short and long-term while utilizing their capabilities either through exploration or exploitation. Two major schools of thought have developed describing how competitive advantage and performance might be achieved. The competitive positioning view (CPV) particularly associated with works of (Porter, 1980, 1985), adopts a so-called ‘outside-in’ process by which factors in external environment, including the industry and the market in which the firm operates and competes, are analyzed before an internal analysis of the organization is carried out, it suggests ‘Five Forces’ model of how to achieve superior performance and competitive advantage (Peters, Siller, & Matzler, 2011). According to this view, a firm is successful when it successfully implements a range of strategies required by the external environment (known through external orientation) (Hanson, Dowling, Hitt, Duane Ireland, & Hoskisson, 2011). RBV is the second school of thought advocates an ‘inside-out’ process (Lockett, Thompson, & Morgenstern, 2009), RBV process focuses primarily on internal analysis such as firm's ownership of different types of resources and capabilities which enable firms to develop different strategies (dominant logic) keeping in view the competitors move in the external environment (Javidan, 1998). Organization competitive advantage and performance depends on the ownership of specific resources with specific characteristics such as (‘VRIN’) valuable; rare; inimitable, and non-substitutable (Barney, 1991). Dominant logic is an intangible rare, valuable inimitable and non-substitutable resource of the firm and to this end (Prahalad, Hamel, & June, 1990) suggested that these resources can be configured to achieve superior performance through the exploitation of core competencies. In a nutshell (Lockett et al., 2009) concluded that industry characteristics are important and that the internal focus of RBV and the external focus of CPV should be viewed as complementary, Mintzberg and Quinn (1996) argue that a firm's resource endowment i.e. managerial capabilities [the focus of RBV] determines the activities (through scanning) that the firm can perform at any point in time. These activities are important because it is only with reference to them that competitive advantage relative to the market and competitors i.e. competitive intensity can be evaluated (Fig. 1). Taken together, we posit that:

H4a. Greater competitive intensity has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between dominant logic (information filter) and firm performance.

H4b. Greater competitive intensity has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between dominant logic (learning and routines) and firm performance.

MethodologySample and data collectionWe obtained our data through a questionnaire sent to SMEs in Anhui province, China. We chose China as a research laboratory because it is one of the world's fastest, largest and emerging economies that possess many important institutional attributes quite similar to other emerging markets which features resources (intangible in particular) constraints that is key to achieve superior performance and gain a competitive advantage in particular by SMEs. Second, we mainly focused on manufacturing firms, as these manufacturing firms represent the core of the value-added activities in the Chinese economy. Finally, the Anhui province especially Hefei is one the fastest economically growing and internationalized regions in China. We derived questions from literature and in-depth interviews with top managers from different SMEs. The questionnaire was designed originally in English and subsequently translated into Chinese by two Chinese professors at the school of public affairs USTC. In order to ensure validity and avoid cultural bias, the Chinese version of the questionnaire was retranslated into English with special attention to avoid significant misunderstanding because of translation. Our respondents include top managers responsible for decision-making in their SMEs because prior research has found that top managers provide valid and reliable data (Zhang, Li, Li, & Zhou, 2010).

Collecting data through questionnaire survey in China for research purpose is difficult as compared to other regions in the world (Liu, Ke, Wei, Gu, & Chen, 2010). In order to make our survey easier and feasible, we worked with a Chinese local service center well-known for its excellent services in SMEs. From the institution, we obtained a sampling pool that included 200 firms (SMEs). Then, from each of these firms, we identified two senior executives who as the key informants. We distributed 400 questionnaires through E-mail to SMEs in different sectors. To encourage response we made follow-up calls and sent reminder emails. After the questionnaires distributed for three weeks, we received 382 completed questionnaires representing a response rate of 95.5% such a high response rate represent the high reputation and efficiency of the SMEs local service center, 54 out of 382 questionnaires collected in total were subsequently eliminated as invalid and incomplete. The number of questionnaires usable for data analysis showing an effective response rate of 85.8%. Respondents in our survey include CEOs and the general managers who are responsible for devising and executing various strategies as well as critical resource allocation decision in their firms. We found no significant difference between responding and non-responding SMEs in terms of size and age of the firms.

MeasuresDependent variableSMEs performance is our dependent variable measured by eight items of efficiency, growth and profit Adapted from prior work Li, Huang, and Tsai (2009). We used a seven-point Likert scale to measure the importance of each item of our questionnaire and model. Respondents were asked to compare their firm's performance to their major competitors in the same industry. Research studies Venkatraman and Ramanujam (1987), Steensma, Barden, Dhanaraj, Lyles, and Tihanyi (2008) mentioned that using subjective measures is a valid alternative when objective measures are not obtainable and they are often used while studying transitioning economies like China. In order to so, we used subjective evaluations of firms’ revenues (Profit), quality of offering (Efficiency), and market share (Growth) (during the last 3 years) compared with major competitors. High (low) scores on the Likert scale indicated firm's performance from “smaller than competitors” to “higher than competitors”. We used mean of the scores on these eight items to evaluate the performance.

Independent variablesDominant logicFollowing Bettis, we regard information filter (pro-activeness and external orientation) and routines (learning and routines) as two distinct dimensions of dominant logic, rather than as two ends of a one-dimensional scale. For information filter, we assessed Pro-activeness using six factors proposed by Obloj et al. (2010). Respondents were asked about these items include: “our firm tries to influence direction of changes in our environment, we often start new initiatives, we do not accept high risk of our new ventures, and our employees often experiment in order to find new, innovative ways of action, implementation of new products has been a priority in our firm for many years now. We used five factors to assess External Orientation these items include ‘Environment of our firm is very complex and difficult to analyze, “Environment of our firm has mainly been the source of opportunities’, ‘The future vision of our firm is very optimistic’, ‘Our competitors are mainly the source of challenges and new initiatives’, ‘Our competitors sometimes act in a dishonest way that limits our development possibilities”. Learning and Routine were also assessed using four factors for learning and four factors for routine also proposed by Obloj et al. (2010). Sample items used for routine are as follows: “we have simple and flat organizational structures, the main process in our firm are well defined and responsibilities are well allocated, our motivational system is developed in a way to force people to act according to instructions, main decisions in our firm are centralized at level of executive board”. Whereas for learning we used sample items include, “Our failures were more a source of frustration than interesting experiences used for firm's improvement, ‘Communication in our firm was always fast, frequent, but sometimes chaotic, ‘We always quickly exit from wrong strategic decisions, ‘Our successes are an important source of information and experience for us, ‘Since the beginning we develop and improve our business model incrementally”

Dynamic managerial capabilitiesHelfat and Peteraf (2003) insightfully identified the three attributes underpinning dynamic managerial capabilities as managerial human capital, managerial social capital, and managerial cognition. Managerial Human capital was assessed using five factors proposed by (Felício et al., 2012). Respondents were asked to assess the knowledge, experience, professional proficiency, cognitive ability and proactivity of top-level managers. Managerial Social capital has been widely acknowledged in the literature that firms are likely to develop relations with an outsider. Followed the Felício et al. (2012) we assessed the social capital using five items as follows: “status (economic, political, cultural, interlinking (family, work political and sporting), complicity, personal relations (with financial, government and business entities), and social relations (informal relations).” Managerial Cognitions was assessed using four items proposed by Vanharanta and Easton (2010). A sample item is as follows: “Assembling an action sequence of the past and specifying parameters regarding the future, Ability to identify and evaluate internal problem areas, Ability to inspect and evaluate risk, evaluate the outcomes.”

1.1.1.1Competitive intensityWe adopted six items from Desarbo, Di Benedetto, Song, and Sinha (2005) measurement scale on environmental turbulence that specifically relates to competitive intensity. The same instrument was also adapted by others management Wilden et al. (2013), business Auh and Menguc (2005) and marketing researchers Murray, Gao, and Kotabe (2011) to study the moderating role of competitive intensity. The target audience was asked to assess the competitive situation of the market, including price competition, the existence of promotion wars and competitors moves (strategies). These items were coded on a seven-point scale anchored at 1=‘strongly disagree’ to 7=‘strongly agree’.

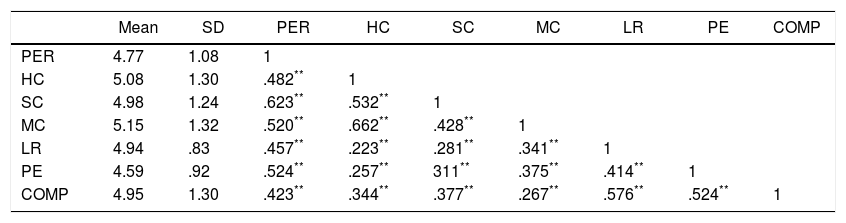

Empirical resultsAssessment of the measuresTable 1 shows the means, standard deviations and correlations among the variables examined and tested in our study. SMEs performance is positively correlated with dynamic managerial capabilities, dominant logic and competitive intensity.

Mean, standard deviation and correlations.

| Mean | SD | PER | HC | SC | MC | LR | PE | COMP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PER | 4.77 | 1.08 | 1 | ||||||

| HC | 5.08 | 1.30 | .482** | 1 | |||||

| SC | 4.98 | 1.24 | .623** | .532** | 1 | ||||

| MC | 5.15 | 1.32 | .520** | .662** | .428** | 1 | |||

| LR | 4.94 | .83 | .457** | .223** | .281** | .341** | 1 | ||

| PE | 4.59 | .92 | .524** | .257** | 311** | .375** | .414** | 1 | |

| COMP | 4.95 | 1.30 | .423** | .344** | .377** | .267** | .576** | .524** | 1 |

N=328.

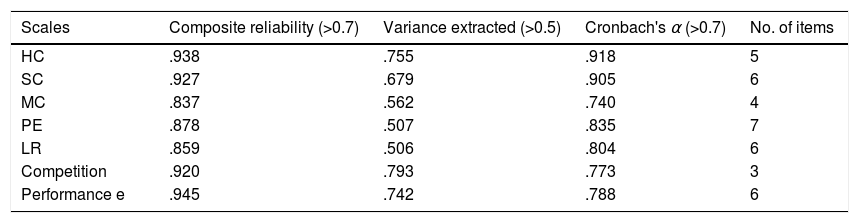

The measurement scales for firm performance, dynamic managerial capabilities, and competitive intensity have been validated in prior studies. To confirm that they maintain the psychometric properties required in our sample, we performed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Hulland (1999) proposes that in order to be valid an indicator must fulfill three necessary conditions: (1) all factor loadings must be significant (t>1.96; p<0.05), (2) the indicators must be greater than 0.5, and (3) each item's value of individual reliability (R2) must be above 0.5. In our model all the items loaded significantly on their corresponding latent construct i.e. DMC (HC, SC, and MC) ranging from .690 to .816, DL (PE and LR) from .663 to .930; competitive intensity from .876 to .869 and firm performance from .795 to .900, thereby providing evidence of convergent validity. Table 3 presents the internal consistency of the scales showing Alpha Cronbach coefficient (α≥0.7), acceptable according to the minimum recommended value of 0.7 (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 2004) (see Table 2). Further, composite reliability of all the constructs is greater than 0.7 and average variance extracted (AVE) greater than 0.5, are also acceptable according to (Hair et al., 2004) (see Table 2). Therefore we concluded that each construct of our study was unique and captured phenomena that other measures did not.

Internal consistency of scales used.

| Scales | Composite reliability (>0.7) | Variance extracted (>0.5) | Cronbach's α (>0.7) | No. of items |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | .938 | .755 | .918 | 5 |

| SC | .927 | .679 | .905 | 6 |

| MC | .837 | .562 | .740 | 4 |

| PE | .878 | .507 | .835 | 7 |

| LR | .859 | .506 | .804 | 6 |

| Competition | .920 | .793 | .773 | 3 |

| Performance e | .945 | .742 | .788 | 6 |

DMC=dynamic managerial capabilities; DL=dominant logic.

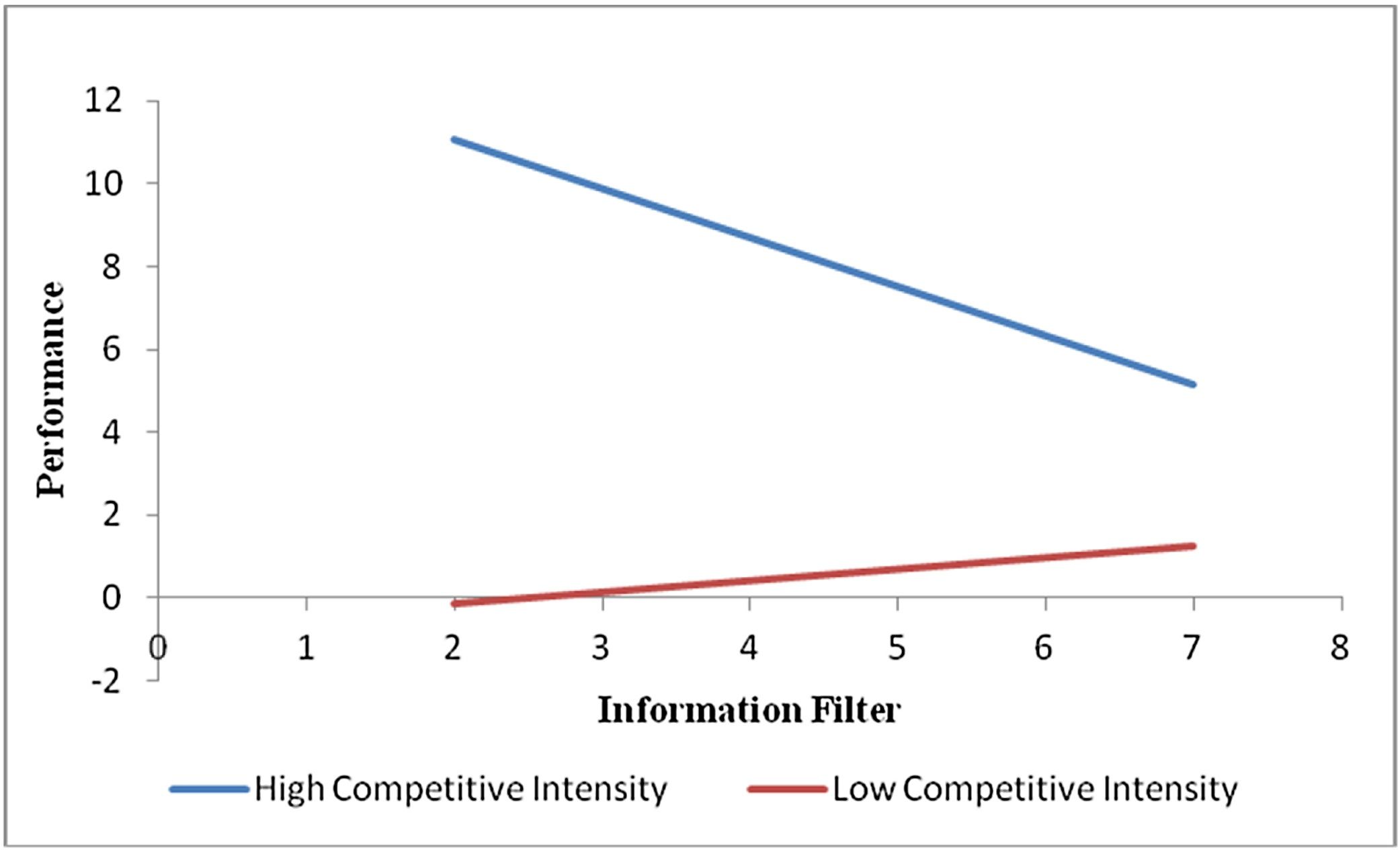

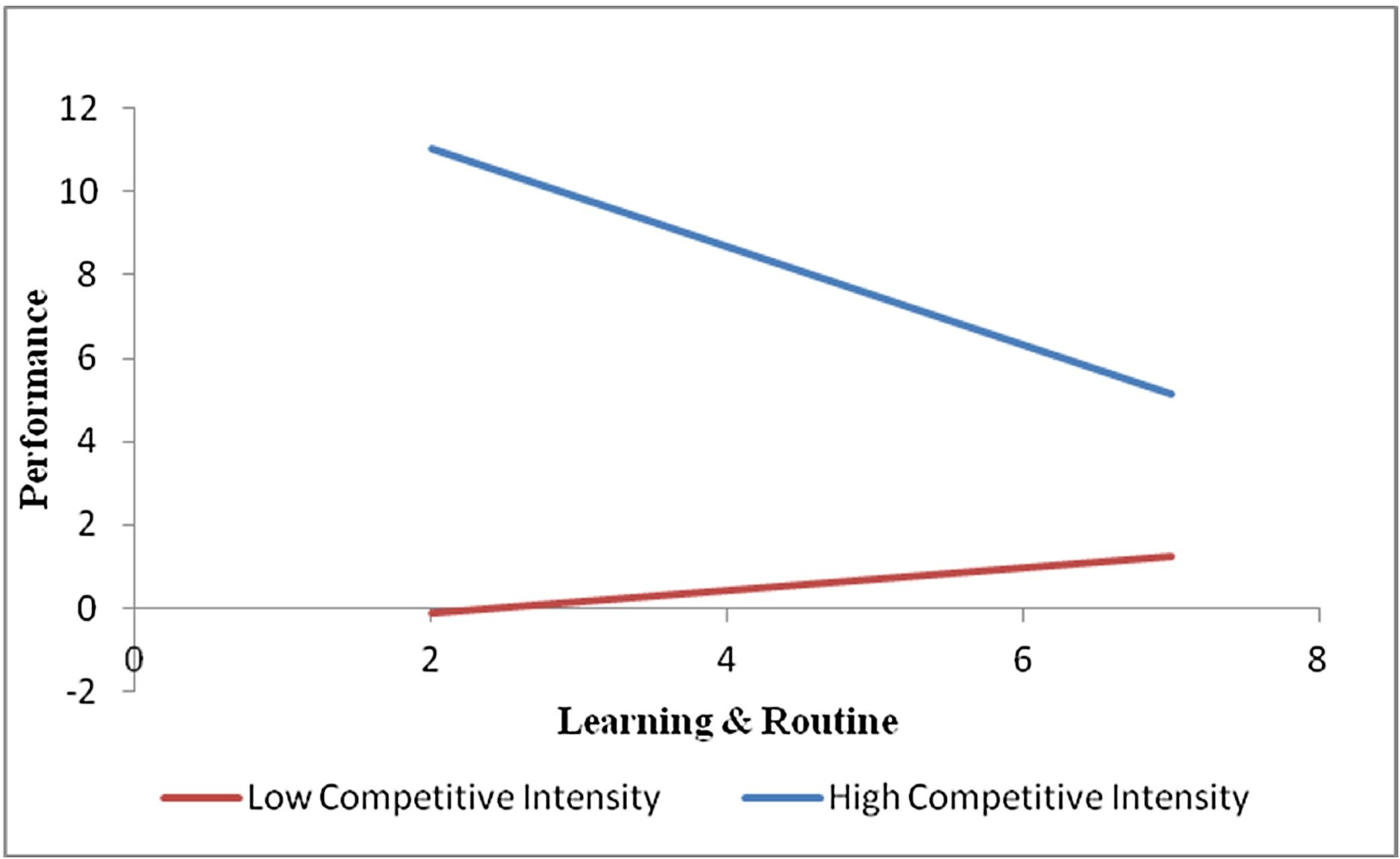

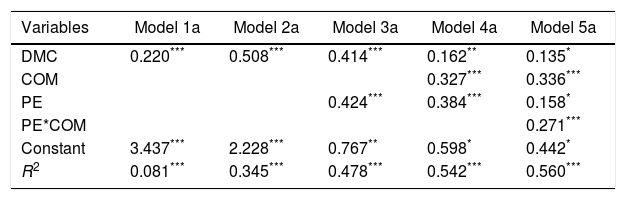

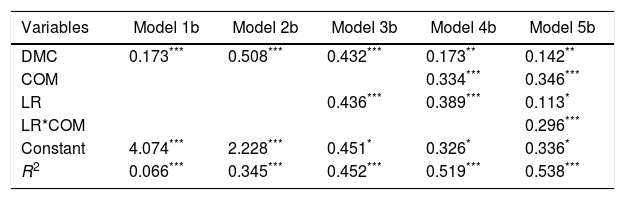

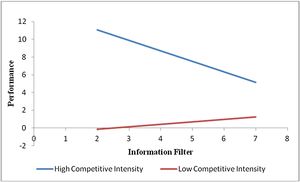

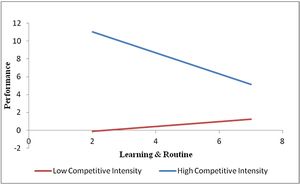

To examine how dominant logic mediates between dynamic managerial capabilities and firm's performance as well as to check the moderating effect of competitive intensity we adopted regression analysis approach. Tables 3 and 4 report the results. The results of Model 1a supports Hypothesis H1a that dynamic managerial capabilities (DMC) have a positive and significant effect on information filter (pro-activeness and external orientation) (βPE=0.652, p<.001) of the top management team of the firm. In Model 2a the coefficient of the interaction between firm performance and dynamic managerial capabilities is (βDMC=0.507, p<.001) meaning that dynamic managerial capabilities (i.e. HC, SC and MC) has a significant and positive effect firm performance and support H1c. Our empirical results i.e. Model 2a and Model 3a also support H3a that dominant logic (information filter) plays a mediating role between firm performance and dynamic managerial capabilities (βPE=0.424, p<.001) the mediating effect of information filter is also presented in Fig. 2. Results of this study also support H4a (see Model 4a and 5a) that competitive intensity moderates the relationship between dominant logic (information filter) and firm performance (βCOM=0.327, p<.001) and (βCOM×PE=0.246, p<.001) meaning that higher the competitive intensity in the market the stronger the relationship between dominant logic (information filter) and firm performance. As in our theoretical framework dominant logic has two dimensions (information filter and learning and routines), we also analyzed data for the second stream of dominant logic and empirical results (Model 1b) supports H1b (βDMC=0.173, p<.001) meaning that dynamic managerial capabilities (HC, SC, and MC) has positive and significant effect on dominant logic (learning and routines) in transition economies such as China. Dominant logic (learning and routines) mediates the positive effect of dynamic managerial capabilities on firm performance i.e. the relationship between DMC and firm performance and results of this study (see Models 2b and 3b) also support our hypothesis H3b (βLR=0.436, p<.001) and (βDMC=0.432, p<.001). Model 4b and Model 5b supports H4b that competitive intensity moderates the relationship between dominant logic (learning and routines) and firm performance (βCOM=0.334, p<.001) and (βCOM×LR=0.262, p<.001) (also see Fig. 3), meaning that the higher the competition (competitive intensity) in highly volatile markets the stronger the relationship between dominant logic (learning and routines) and firm performance. Our results also support H2a and H2b that firms learning and routines and high level of pro-activeness will lead to superior performance. We observe a positive relationship between dominant logic and SMEs performance (βPE=0.88, p<.001) and (βLR=0.72, p<.001). Empirical results of our study support all of our hypotheses.

Results of regression analysis.

| Variables | Model 1a | Model 2a | Model 3a | Model 4a | Model 5a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMC | 0.220*** | 0.508*** | 0.414*** | 0.162** | 0.135* |

| COM | 0.327*** | 0.336*** | |||

| PE | 0.424*** | 0.384*** | 0.158* | ||

| PE*COM | 0.271*** | ||||

| Constant | 3.437*** | 2.228*** | 0.767** | 0.598* | 0.442* |

| R2 | 0.081*** | 0.345*** | 0.478*** | 0.542*** | 0.560*** |

N=328.

Results of regression analysis.

| Variables | Model 1b | Model 2b | Model 3b | Model 4b | Model 5b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMC | 0.173*** | 0.508*** | 0.432*** | 0.173** | 0.142** |

| COM | 0.334*** | 0.346*** | |||

| LR | 0.436*** | 0.389*** | 0.113* | ||

| LR*COM | 0.296*** | ||||

| Constant | 4.074*** | 2.228*** | 0.451* | 0.326* | 0.336* |

| R2 | 0.066*** | 0.345*** | 0.452*** | 0.519*** | 0.538*** |

N=328.

This study contributes to the existing literature in the following ways. The first is the empirical contribution that dynamic managerial capabilities and dominant logic are relevant for SMEs in emerging economies like China. Existing literature suggests that theories generated and applied in western and developed countries may not be fully applicable to societies with different socioeconomic conditions (Lin & Germain, 2003). China is an emerging market economy with socialist characteristics and has many features in common with other emerging market economies. An empirical examination of applicability of theory and necessary adjustment in China is a meaningful endeavor. Being one of the largest and fastest growing economies in the world empirical findings in Chinese context provide important implications for SMEs operating in other emerging economies of the world (Zhou & Li, 2010). Our empirical findings show that dynamic managerial capabilities and dominant logic have a significant impact on firm performance in a highly competitive environment of emerging economies. Therefore firms (SMEs) should confidently nurture and invest into the development of dynamic managerial capabilities and dominant logic of top management to better address environmental changes and avoid capability traps.

Previous empirical studies of RBV and dynamic managerial capabilities view (DMCV) verify and treat different subjects separately. This study uses a single group of items i.e. dynamic managerial capabilities, dominant logic, competitive intensity and firm performance and applies step by step empirical process to examine the applicability of the RBV, dominant logic and DMCV especially in highly volatile environments in transition economies like China. We examined 328 SMEs in China (Anhui province) and found that SMEs can better perform and achieve competitive advantage possessing greater intangible resources (dynamic managerial capabilities and dominant logic) as compared to their counterparts in highly competitive and volatile markets (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). Our study findings indicate that accumulation of intangible resources (VRIN) increases firm performance. However different studies Barney and Arikan (2001) and Newbert (2007) discussed that the strength of RBV depends on the volatility of market environment if it is low or medium firms can achieve superior performance and competitive advantage through VRIN resources. Findings of our study indicate that dynamic managerial capabilities (i.e. HC, SC, and MC) and dominant logic (information filter and learning and routines) are the intangible resources and the main source of competitive advantage and SMEs performance. SMEs that can rapidly and effectively integrate, learn and reconfigure their resources (both internal and external) can easily adapt to the ever-changing and competitive environment and enhance performance. Dominant logic through information filter and learning and routines sense not only the internal but also the external environment for opportunities and threats and help SMEs nurture their dynamic managerial capabilities of the top management team in order to achieve superior performance. In a nutshell, we can say that RBV is still somewhat effective and SMEs with VRIN resources can achieve superior performance, however, these study findings show that the DMCV and dominant logic together with RBV can better explain firm performance. Despite the importance of intangible resources, there has been a less empirical investigation on the relationship between a firm's dynamic managerial capabilities, dominant logic, and the firm's performance, the main purpose of this paper is to contribute and discuss this missing link largely ignored in the literature. Today every organization in hyper-competitive and innovative environment faces the main challenge of how to achieve and sustain competitive advantage and long-term performance (Finster & Hernke, 2014). Our endeavor in this regard include to bridge the gap while adding to the existing incomplete research and linking dynamic managerial capabilities (HC, SC and MC) (Eggers & Kaplan, 2013; Kor & Mesko, 2013) to dominant logic and how these factors affect firm performance, especially in emerging economies like China and our study findings, support all these with empirical results. Another significant contribution is the role of competitive intensity as a moderator between firm performance and dominant logic (information filter and learning and routines). The results of this study support its moderating role. The main reason may be that as there is severe competition in the market environment become more turbulent and firms become more sensitive and need to cultivate and invest in intangible resources in particular higher level of dynamic managerial capabilities and dominant logic to cope with (Schindehutte & Morris, 2001). Our empirical results confirm the positive effect of dynamic managerial capabilities and dominant logic on firm performance in highly competitive and volatile environments. This is an original contribution particularly in the context of Chinese SMEs as previous research studies stress the lack of research analyzing how dynamic managerial capabilities and other intangible resources influence the firms’ performance (Barbero, Casillas, & Feldman, 2011).

Limitations and future researchDespite the interesting results of our study, the current research study has some limitations related to the research design and data availability. First, though the study has focused on three dynamic managerial capabilities, some others may not be included, for example, sensing and seizing capability (Teece, 2007), adaptive capability (Wang & Ahmed, 2007) or absorptive capacity and learning capability or others not identified. In future, these capabilities may be investigated in more details especially in emerging economies. Future research could address some important research questions not addressed here; such as how intangible VIRN resources like dynamic managerial capabilities and dominant logic affect innovation in SMEs, how SMEs resources (intangible) serve as the foundation of dynamic managerial capabilities and dominant logic affect the formation of dynamic managerial capabilities and dominant logic and subsequently innovation and how firm's characteristics (e.g. culture, top management team, and structure) affect innovation process in SMEs especially in the context of China. This study is limited in that the analysis is based on perceptual data that could be somewhat subjective (Nakayama & Sutcliffe, 2005). This perceptual approach creates difficulties for managers of SMEs in applying the research results to practical problems involving specific businesses of SMEs. Data in the study were collected from SMEs in China by questionnaires, we are still cautious in inferring the direction of causality among the key constructs due to the cross-sectional nature of our data and research design. A longitudinal design (interviews), cross-validation of findings, and additional data sources (e.g. panel data) would be more effective in future to assess the causality of the hypothesized relationships. Gender diversity in the top management team of firms provides different work styles, values, capabilities, experience, and points of view that can further strengthen the influence of dynamic managerial capabilities and dominant logic on firm performance. Existing research that analyzed demographic diversity in top management teams has largely ignored the effect of gender (Carpenter, Geletkancz, & Sanders, 2004). It would be interesting to address this factor in future research. Finally, although the use of dynamic managerial capabilities and dominant logic and firm performance may be globally relevant to less developed SMEs, the findings of this study are for Chinese SMEs only because of its fast changing nature these intangible resources are more prominent for firms operating in China, this presents a potential limitation of the results to be generalized to other emerging economies of the world, a more detailed research is needed in other developing economies of the world in future.