The application and monitoring of quality criteria in information and therapeutic patient education can identify areas to improve care. The objectives of this study were: (1) To analyze the characteristics of patient information materials, educational activities, and self-management programs, and (2) to determine health care provider (HCP) proposals on therapeutic patient education.

Materials and methodsUsing a cross-sectional study, an online questionnaire was sent to hospital departments in a high complexity reference hospital from September to December 2013 to record: (a) information materials, (b) patient educational activities, and self-management program characteristics, (c) HCP proposals. The materials were analyzed using Health Promoting Hospitals (HPH) recommendations.

Results(1) An analysis was performed on 258 materials (leaflets [54%]) for chronic patients (86%), acute patients (7%), and the general population (7%). More than half (55%) lacked the authors, and 43% the year issued, and 69% followed HPH recommendations. (2) An evaluation was made of 70 educational activities and 37 self-management programs addressed to patients/relatives with diabetes/obesity, musculoskeletal disorders, COPD/asthma, pelvic-floor disorders, transplantation, bowel-inflammation/liver disease, hypertension, cancer, heart failure, acquired immune deficiency syndrome, chronic renal insufficiency, splenectomy, anticoagulation and older-patient dependence. The structure, process and outcome evaluation varied. (3) HCP proposals included: standardization of materials criteria, web accessibility, list of accredited websites, cross-sectional use, and HCP training in self-management education.

ConclusionsThe online questionnaire showed the weaknesses and strengths of patient information and education, and can be used to monitor their quantity and quality. These results help in the definition of a useful model to improve patient information and education policies.

La aplicación y el seguimiento de criterios de calidad en la información y educación terapéutica (ET) permite identificar oportunidades de mejora asistencial. Los objetivos fueron: (1) Analizar materiales informativos, actividades educativas y programas educativos estructurados y (2) Determinar las propuestas de los profesionales de la salud (PS) sobre información y ET.

Materiales y métodosEstudio transversal en hospital de alta complejidad y de referencia. Se envió cuestionario online a los departamentos del hospital (septiembre-diciembre 2013) registrando: (a) Materiales informativos, (b) Actividades educativas y características de los programas educativos estructurados, y (c) Propuestas de los PS. Los materiales se analizaron utilizando recomendaciones de Hospitales Promotores de la Salud (HPS).

Resultados(1) Se analizaron 258 materiales (folletos [54%]) para pacientes crónicos (86%), pacientes agudos (7%) y población general (7%); el 55% carecía de autores y el 43% de año de edición; el 69% siguió las recomendaciones de los HPS; (2) Se identificaron 70 actividades educativas y 37 programas estructurados dirigidos a pacientes/familiares con diabetes/obesidad, trastornos musculoesqueléticos, EPOC/asma, trastornos del suelo pélvico, trasplante, inflamación intestinal/enfermedad hepática, hipertensión, cáncer, insuficiencia cardíaca, SIDA, insuficiencia renal crónica, esplenectomía, anticoagulación y dependencia en pacientes mayores. Estructura, proceso y evaluación de resultados variaron, y (3) Las propuestas de PS fueron: criterios para unificar materiales, accesibilidad vía web, lista webs acreditadas, utilización transversal y, formación de los PS en ET.

ConclusionesEl cuestionario online mostró fortalezas y debilidades de la información y educación del paciente, y puede utilizarse para monitorizar su cantidad y calidad. Estos resultados permiten definir un modelo para mejorar la información y la educación terapéutica.

One common approach of different Health Organization Policies to improve the management of non communicable diseases (NCDs) emphasizes patient-centered care.1 A key element of this approach is the active role of patients and caregivers which requires an adequate level of health literacy.2 Assessment of health literacy can be used to not only measure the efficacy of communication between health care providers (HCP) and their patients in a hospital setting but also as a tool for quality improvement.3 Moreover, the level of health literacy in NCDs has a positive impact on health outcomes.4

Some examples of health literacy improvement strategies include the identification of patients with low literacy,5 self-management education,6 support to decision making processes,7 and expert patients.8 However, successful improvement of health literacy is mainly achieved with a combination of several strategies, and structured education and information are essential for shared decision making between patients and HCP.

Many educational approaches have been evaluated especially in diabetes,9 chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases10 and musculoskeletal disorders.11 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Health Technology Appraisal on patient education for diabetes defines a structured self-management education program as “a planned and graded program that is comprehensive in scope, flexible in content, responsive to an individual's clinical and psychological needs, and adaptable to his or her educational and cultural background.”12

Information and patient education activities are undertaken by both hospital and primary health care services, but they are not homogeneous, and priorities are not always based on population needs. The quality of information materials also varies greatly.13

Many scientific societies consider that it is also necessary to implement quality standards related to self-management education programs in clinical practice. Thus, the first evaluation of quality standards of educational activities for patients/relatives in our hospital was made in 2007.14 The results of this evaluation showed that the application of quality standards to educational programs was useful and suggested that standard-based software can provide information on trends in patient education. In 2014 the interdisciplinary Working Group of Information and Therapeutic Education (GTIET) was created with the aim of improving patient education and materials.

Therefore, the main objective of this study was to describe the current patient education activities performed in our hospital and compare this with was reported in the 2007 study.14 Furthermore, we analyzed the informative materials used in the hospital and HCP proposals.

Material and methodStudy design and settingA cross-sectional study was carried out in the highly specialized, 850-adult bed high complexity reference hospital, university Hospital Clínic of Barcelona with a reference population of 520,000 inhabitants.

Data was collected from September to December 2013 using an online survey sent to HCPs, registering information about informative materials, educational activities, self-management programs and HCP proposals related to these areas.

The objectives and methodology used were explained to the Nursing and Medical Directors of each department, who then sent the survey to HCPs involved in patient education.

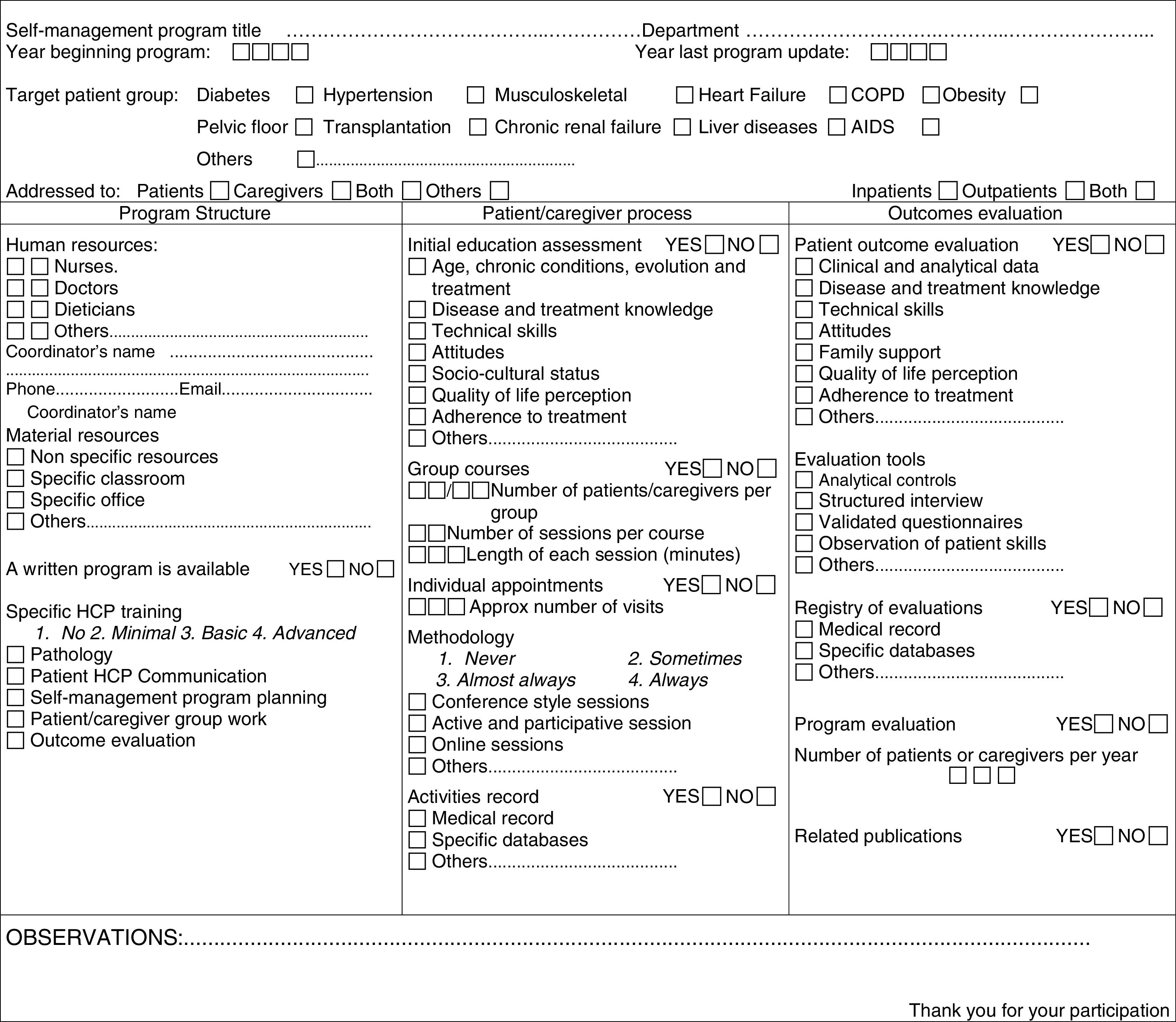

The online surveyThe online survey used (Lime Survey®) was similar to the previous survey made in 2007.14 Given the lack of validated questionnaires, we used a non-validated questionnaire based on the translation and generic adaptation of Quality Standards for Diabetes Self-management Education.15,16 This adhoc survey has 4 fields: (a) informative materials, (b) educational activities in specific situations, (c) structured self-management education programs, and (d) HCP proposals.

- a.

Informative materials refer to materials in any written or audiovisual format. Diagnostic test requests or informed consents were not considered as patient information documents. A copy of the materials was sent to the Communication Department. The items recorded were: department identification, title, group of patients and/or relatives, material type, authors, edition year and promoters.An interdisciplinary working group composed by experts on patient education, communication, epidemiology and quality, nursing care, information systems and a patient analyzed the quality of the materials.The Catalan Network of Health Promoting Hospitals recommendations17 on linguistic and typographic legibility were used as the gold standard.

- b.

Educational activities in specific situations refer to all structured educational activities focused on self-care education technical skills, diet, exercises and other self-care activities related to disease and/or treatment. The items included: department identification, title, group of patients and/or relatives, location of the activity (inpatient, outpatient, home hospital, day hospitalization, emergency, classroom education, other), educational approach (individual, group, online, other), brief description of the activity, written procedure available or not and observations.

- c.

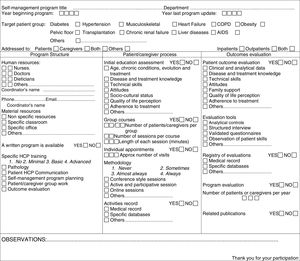

Structured patient education self-management programs refer to structured programs available with a written definition of structure, the process that follows patients/caregivers and evaluation of results. Fig. 1 shows the items recorded.

- d.

Health care provider proposals were collected using the following open questions:

- •

What other informative materials (in any format) do you think would be useful?

- •

What other groups of patients should follow educational activities or a structured self-management program?

- •

What suggestions would you make to improve therapeutic patient education?

Descriptive statistical analyses of information materials, educational activities, structured self-management programs and the HCP proposals were made. We used the Lime survey database and exported data to Microsoft Excel.

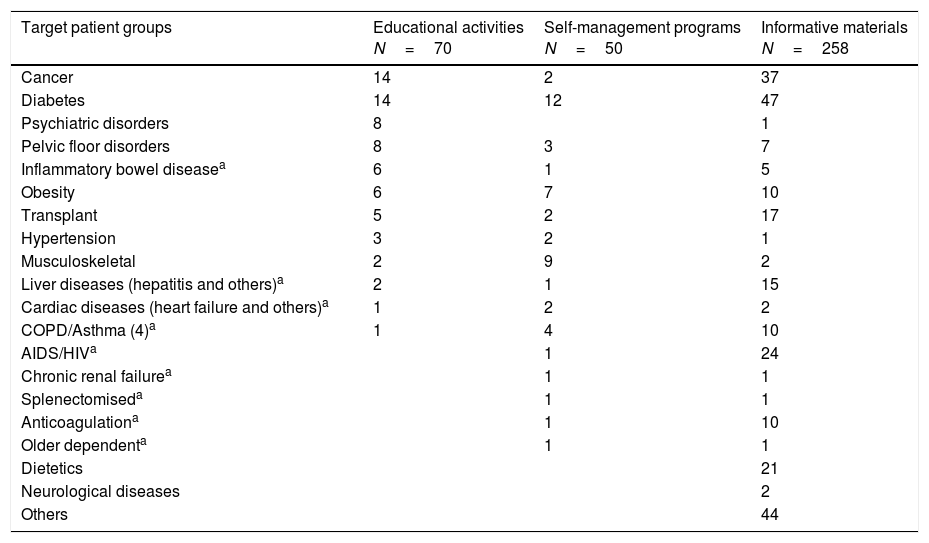

ResultsInformative materialsOf the 325 registries, 258 materials were analyzed. Most were aimed at patients with NCDs and/or their relatives (86%), involving mainly diabetes (18%) and cancer (14%) (Table 1), while 7% were addressed to acute problems and 7% to the general population. The most frequently used format was leaflets (54%), with other materials being classified as books (11%), DVDs or videos (7%), websites (6%) or another format (22%). The promoter was the Hospital Clínic in 60% and the pharmaceutical industry in 10%, while the remaining promoters included scientific societies, patient associations, and the Catalan Health Department among others. Analysis by the interdisciplinary working group showed that 55% of the 258 materials had no author and 43% of the materials analyzed did not include the year of edition. We observed a high variability in fulfilling the content criteria and linguistic and typographic legibility. However, 69% of the materials were classified as acceptable according to The Catalan Network of Health Promoting Hospitals recommendations,17 while the remaining materials required improvement.

Target patient groups. Educational activities, self-management programs and informative materials.

| Target patient groups | Educational activities N=70 | Self-management programs N=50 | Informative materials N=258 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 14 | 2 | 37 |

| Diabetes | 14 | 12 | 47 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 8 | 1 | |

| Pelvic floor disorders | 8 | 3 | 7 |

| Inflammatory bowel diseasea | 6 | 1 | 5 |

| Obesity | 6 | 7 | 10 |

| Transplant | 5 | 2 | 17 |

| Hypertension | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Musculoskeletal | 2 | 9 | 2 |

| Liver diseases (hepatitis and others)a | 2 | 1 | 15 |

| Cardiac diseases (heart failure and others)a | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| COPD/Asthma (4)a | 1 | 4 | 10 |

| AIDS/HIVa | 1 | 24 | |

| Chronic renal failurea | 1 | 1 | |

| Splenectomiseda | 1 | 1 | |

| Anticoagulationa | 1 | 10 | |

| Older dependenta | 1 | 1 | |

| Dietetics | 21 | ||

| Neurological diseases | 2 | ||

| Others | 44 |

We analyzed 70 registered educational activities. The main target groups included cancer and diabetes patients (Table 1).

Educational activities were aimed at patients and families/caregivers (72%), patients alone (24%) and the general population (4%).

Most of these activities were performed in inpatients. The educational activity was performed individually in 70% of cases, in small groups of patients in 19% and with a mixed approach in 11% of cases. The types of educational activities were:

- •

Training about technical skills regarding inhalers, injections, care of ostomies, catheters and drains, etc. and the use of computer tools for telematic visits.

- •

Counseling about lifestyles and cardiovascular risk factors, especially hypertension, dyslipidemia and smoking.

- •

Education about at-home treatment and prevention of acute complications.

- •

Training on topical treatments.

- •

Workshops on behavior modification.

We identified 37 structured self-management education programs. The same program can be used to meet the needs of more than 50 different groups of patients, especially those with diabetes, locomotor system diseases, obesity, COPD and asthma (Table 1). The programs are mainly aimed at outpatients; 76% were addressed to patients and caregivers, 21% only to patients and 3% only to family members/caregivers.

The HCPs involved in the programs were nurses (92%), physicians (49%), dieticians (14%). Other HCPs that were involved less frequently were midwives, social workers, physiotherapists and psychologists, some of whom participated in 24% of the programs. Ninety percent of the programs were written: 89% including objectives, contents and methods; 86% defined the process followed by the patient/family in the program; 86% evaluated results; 80% made periodic reviews of program content. An interdisciplinary approach was used in 77% of the programs.

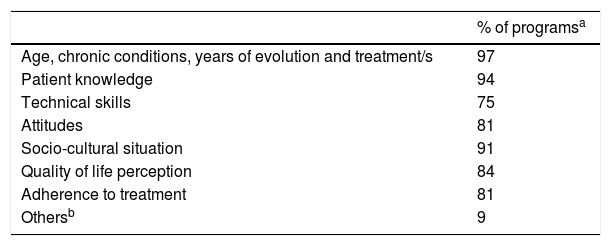

Patient and caregiver process in the programAn initial patient assessment was made in 94% of the programs, showing differences in the items assessed among the different programs (Table 2). An individual approach was used in 95% of the programs (1–10appointments/patient) and group courses in 62% (5[SD: 3.9] average number sessions with an average duration of 100[SD: 19] minutes/session with a maximum of 15 patients and caregivers per group); 30% of the programs involved telematic appointments (57% from 1 to 5 appointments). Most referred active and participative methodology (94%) and provided written material (78%).

These educational activities were recorded in 97% of programs; 86% were recorded in the medical record, and 31% used specific databases.

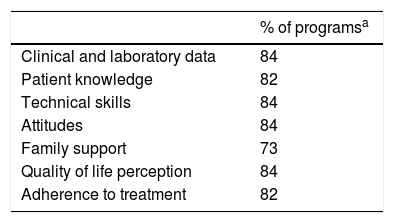

Outcome evaluationEvaluation of patient outcome was made in 89% of the programs (Table 3). Evaluation tools included analytical tests in 60% of the programs, structured interviews in 39% and validated questionnaires in 79%. Technical skills were evaluated by HCP observation.

Final assessment of patient outcomes.

| % of programsa | |

|---|---|

| Clinical and laboratory data | 84 |

| Patient knowledge | 82 |

| Technical skills | 84 |

| Attitudes | 84 |

| Family support | 73 |

| Quality of life perception | 84 |

| Adherence to treatment | 82 |

Patient outcome evaluation of the programs was recorded in the medical record in 84% and in specific databases in 33%. Although most of the programs performed some type of program evaluation (31 programs) only 16 published the outcomes.

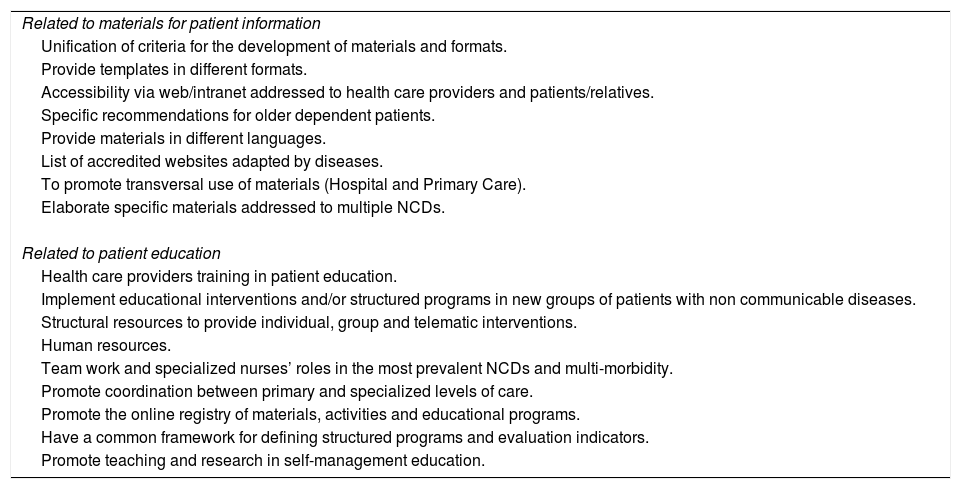

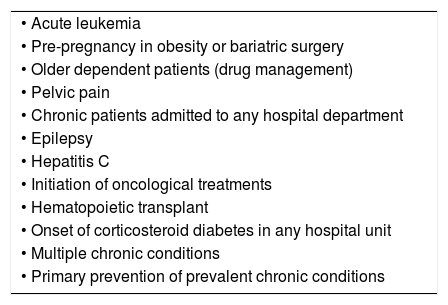

Health care provider proposalsHCP proposals are shown in Table 4. The most frequent proposals on patient information materials regarded the need for standardization of criteria and templates for the development of materials and online accessibility to all existing informative materials. Regarding patient education, the HCPs mainly requested specific training on planning and evaluation of educational programs to improve HCP knowledge and communication skills, questionnaire validation, and face-to-face or group or online patient education approaches. Another frequent proposal was to implement educational interventions and/or structured programs in all groups of patients who, according to the WHO,18 are susceptible to educational intervention highlighting the specific new target groups shown in Table 5.

Health care provider proposals.

| Related to materials for patient information |

| Unification of criteria for the development of materials and formats. |

| Provide templates in different formats. |

| Accessibility via web/intranet addressed to health care providers and patients/relatives. |

| Specific recommendations for older dependent patients. |

| Provide materials in different languages. |

| List of accredited websites adapted by diseases. |

| To promote transversal use of materials (Hospital and Primary Care). |

| Elaborate specific materials addressed to multiple NCDs. |

| Related to patient education |

| Health care providers training in patient education. |

| Implement educational interventions and/or structured programs in new groups of patients with non communicable diseases. |

| Structural resources to provide individual, group and telematic interventions. |

| Human resources. |

| Team work and specialized nurses’ roles in the most prevalent NCDs and multi-morbidity. |

| Promote coordination between primary and specialized levels of care. |

| Promote the online registry of materials, activities and educational programs. |

| Have a common framework for defining structured programs and evaluation indicators. |

| Promote teaching and research in self-management education. |

NCDs: non communicable diseases.

New target patient groups to self-management programs proposed by health care providers.

| • Acute leukemia |

| • Pre-pregnancy in obesity or bariatric surgery |

| • Older dependent patients (drug management) |

| • Pelvic pain |

| • Chronic patients admitted to any hospital department |

| • Epilepsy |

| • Hepatitis C |

| • Initiation of oncological treatments |

| • Hematopoietic transplant |

| • Onset of corticosteroid diabetes in any hospital unit |

| • Multiple chronic conditions |

| • Primary prevention of prevalent chronic conditions |

This study shows how a register of therapeutic patient education activities and programs, such as those proposed in the 2007 inventory,14 allowed the follow-up and assessment of quality standards of the therapeutic patient education programs carried out in our hospital.

The use of an electronic registry identified the target groups of this kind of activities and assessed the quality standards of the structured programs. Furthermore, this registry identified all the informative materials used in the center as well as HCP proposals. It also demonstrated the relevant role played by a specific interdisciplinary working group (GTIET) which includes patient participation.

We found there was room for improvement in the qualitative aspects of the materials, mainly in relation to legibility and typography. The survey identified many materials for cancer and diabetes; however, based on the characteristics of the hospital reference population and the burden of some of these conditions, the production of materials for highly specialized care, aging populations, people with cognitive disorders or renal diseases or for surgical procedures in general are likely needed.19 Producing clear and evidence-based material is not easy and several local analyses reinforce this view20 and have made recommendations based on commonly accepted criteria.21

The survey identified educational activities mainly devoted to in-patients. The structured self-management education programs identified were largely addressed to prevalent NCDs and were mainly performed in outpatient hospital departments. We observed an increase of the number of structured self-management education programs compared with the previous study in 200714 (37 vs. 27 programs, respectively). Some of the new structured programs originated from sporadic educational activities identified in 2007, increasing awareness of the need for structured educational activities. On comparing the data obtained in these two studies we found that these programs were maintained, and there was a trend to improvement in new target groups, covering the main chronic patients admitted to our hospital.19,22

Diabetes (mainly diabetes Type I) is the leading area of self-management programs in our hospital, followed by musculoskeletal disorders. Coordination between hospital and primary care teams is very clear in the case of diabetes in our health area, with patients and caregivers following the self-management programs according to the type of diabetes and treatment.23 Nevertheless, while in many cases diabetes is a reference model for therapeutic patient education,24 there is room for improvement in people with NCDs other than diabetes. However, as suggested in the information evaluation, there is controversy regarding who should be responsible for these self-management programs. Perhaps, a community approach involving specialists, primary HCPs and community pharmacists,25 could be useful for designing an integral program and avoiding contradictions, duplications or omission of crucial elements. Indeed, the final objective is to design interventions tailored to meet individual needs and improve health outcomes.26

We found that the self-management programs were led by nurses, but in general, the approach is multidisciplinary, including physicians, physical therapists, dieticians and psychologists. Outcome evaluation was done in most of the programs, but it is important to differentiate the evaluation of the program (knowledge, skills) from the impact on health outcomes.

The precise role of the patient in the design of the programs was not identified by the online survey. Nonetheless, the importance of the role of the patient in the evaluation of the materials is of note. In a systematic review of qualitative studies patient involvement was seen as good practice, but sometimes clinicians are skeptical about the day-to-day application of this active participation.27

The proposals of HCP, mainly focused on knowledge and skills training, should be taken into account to improve patient education strategies both in the hospital and in primary care. Indeed, the topics most frequently requested were training regarding planning and evaluation of self-management programs.

The voluntariness of the information collected was a limitation of the study. Despite sending the study presentation, aims, links and a guide to answer the online survey to all medical and nursing staff directors, we obtained a high commitment and participation. However, some materials or activities may not have been included in the final report.

Another limitation of the study was the use of a non-validated questionnaire, although this questionnaire is based on Quality Standards for Self-management Education15,16 and its usefulness has been previously demonstrated.14

One of the strengths of this study is the consistency with previous data from the same hospital.14 This study helped to develop a model of patient information education based on collaborative work of an interdisciplinary working group with patient participation. On the other hand, evaluation of HCP proposals identified some unmet needs. The results obtained demonstrate that the main clinical problems are covered. In addition, priorities related to unmet needs were identified and it is clear that there is an imperative need to involve patients in the production of informative materials.

In relation to recommendations for elaborating informative written materials, there are many consensus references with similar proposals.21 We used the European Health Promoting Hospitals recommendations adapted by the Catalan Health Promoting Hospitals17 project in our analyses of all the information materials. One of these recommendations refers to letter size. This is of relevance as shown in the study by Jansa et al.28 analyzing treatment adherence in patients with multiple NCDs. It was found that 20% of chronic inpatients were unable to read the written information addressed to disease/treatment information due to the small letter size, with the same being found in relation to medical appointments and other information. This study also demonstrated good patient information perception, although only 7% of chronic patients received some type of patient education before discharge. These data underline the need to better organize survival/safety/education during inpatient care and the basic or advanced self-management programs in outpatient and primary care depending on patient needs. In relation to the analysis of materials, a similar study by the Catalan Society of Family and Community Medicine (CAMFIC)29 analyzed the informative materials used at a primary care level in Catalonia and made consensuses editing rules and redesigning the materials available.

Access to updated and understandable health information is a growing citizen demand, as well as an ethical duty and legal obligation. Written information reinforces orally transmitted information during visits or patient education sessions and improves recall capacity and health literacy.

For all these reasons this type of study should be periodically carried out to better monitor the quality of patient information and education and to determine updated HCP needs.

Ours results, unquestionably support what Taylor et al. stated in their review30: “Supporting self-management is inseparable from the high-quality care for long-term conditions. Commissioners and health-care providers should promote a culture of actively supporting self-management as a normal, expected, monitored and rewarded aspect of care.” In this sense, our study shows a useful way to monitor patient information and education in a high complexity reference hospital.

Based on the results of this study we can conclude that the use of educational activities and self-management programs is increasing in our hospital and covers a great variety of NCDs, especially the most prevalent. Nonetheless, the informative materials are not homogeneous and do not cover many unmet needs, making it necessary to improve the quality of patient information materials in our institution.

Online surveys are effective methods to identify and periodically analyze the weaknesses and strengths of patient information materials, educational activities, self-management programs and HCP proposals by different hospital departments and can identify trends and opportunities for improvement.

The practice implications of this analysis led to the definition of hospital policies within the context of an interdisciplinary working group (GTIET) and the development of a patient information and education model.

The need for standardization observed in this analysis promoted the elaboration of three Work Proceedings (WP): WP1-Security education interventions during inpatient hospitalization, WP2-Structured self-management education programs addressed to patients and caregivers in outpatient settings and WP3-Informative material design. Moreover, a specific online informative materials registry (INFOTECA) was created to facilitate accessibility to all HCPs in hospital and primary care. Furthermore, in 2014 an annual course was developed on the methodology of patient information and education addressed to hospital and primary care HCP.

Further studies are needed to evaluate the impact of the improvements in the HCP training and the standardization of information materials and education activities implemented based on the results of this study.

ContributorsMJ, JE, had the original idea for the study and wrote the survey protocol, MJB and MJ evaluated the methodology of the study protocol, and performed the statistical and data analysis. FG, MJ and JV made the online survey. MJ, MJB, JE coordinated the research team and wrote the first draft of the paper reviewed by GTIET members. MJ, MJB, JE wrote the final version of paper and were the guarantors.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agencies.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

We would like to thank the members of GTIET (Roser Cadena, Montse Nuñez, Imma Grau and Mercè Vidal), the departments’ medical and nursing directors and all the health care providers of the Hospital Clinic who develop educational activities for their assistance in data collection. We also thank Serafin Murillo who participated in the interdisciplinary focus group evaluation of informative materials and Donna Pringle for language revision.