Behavioural strategy deals with strategic management from a psychologically informed perspective, integrating emotional aspects in strategic management. Strategic situations can be characterised by a high level of uncertainty, based on the unforeseeable nature of the future and the paradoxical nature of underlying seemingly conflicting choices. Both entail human emotional reactions such as fear and anxiety. Therefore, the micro-foundations of dynamic capabilities theory should pay more attention on the study of fear in the strategic decision-making process. Psychoanalysis and psychotherapy have long-term experience in researching these emotions, such that psychodynamic theory can help with understanding their influences on the thoughts and feelings of the manager, the management team, and the organisation in the process of strategy making.

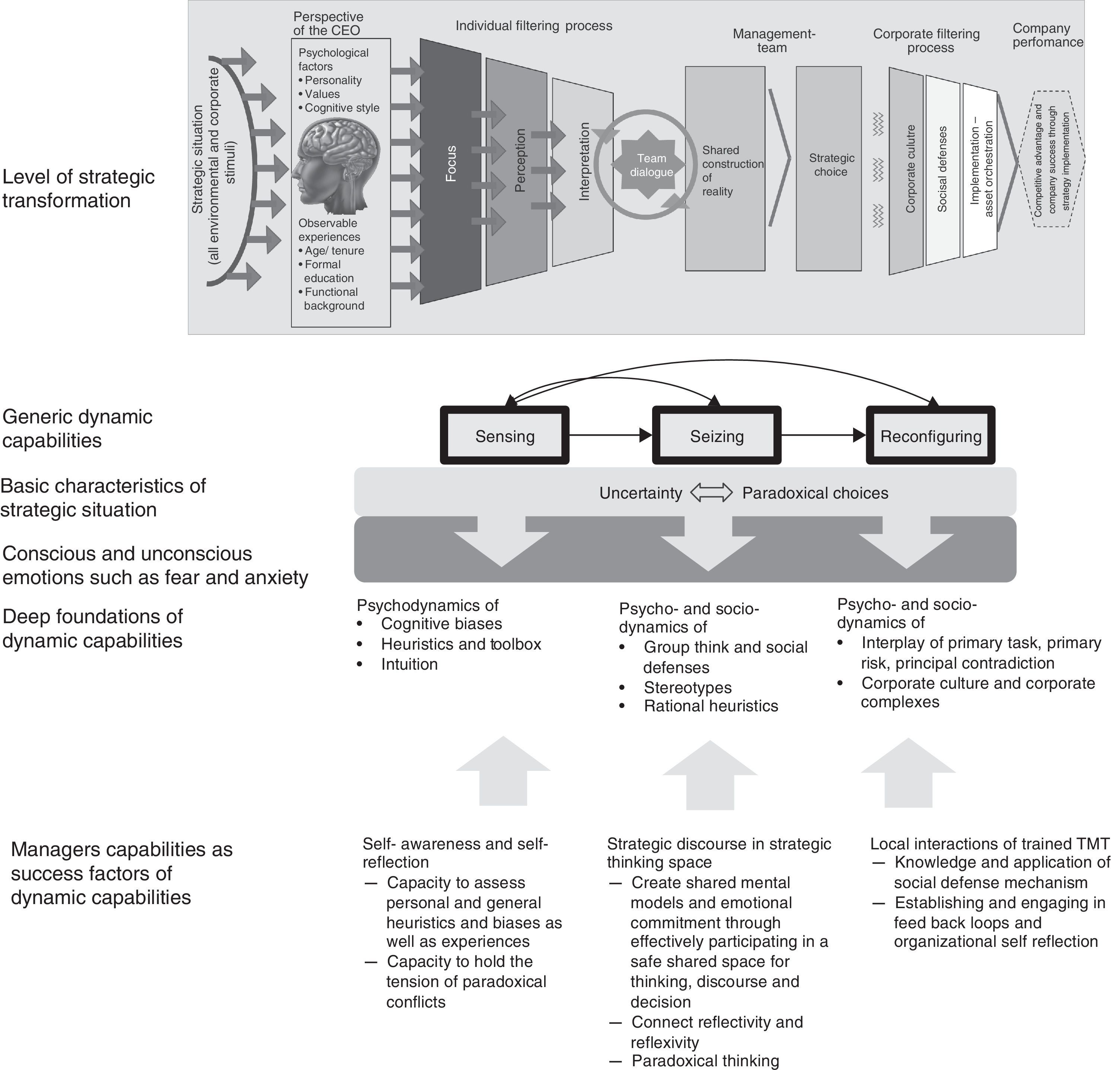

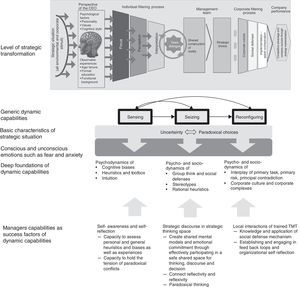

Using the psychodynamic lens in the field of behavioural strategy presents a new and fairly neglected avenue for exploring the more unconscious, ‘deep foundations’ of dynamic capabilities resting on the strategizing manager, the top decision-making team, and the implementing organisation. The three generic dynamic capabilities developed by Teece et al. (1997) and Teece (2007), sensing, seizing and reconfiguring, provide a framework for developing a process-oriented perspective for creating corporate strategy, so that the foundations of dynamic capabilities can be reworked and complemented within this framework. This will also enable the operationalisation of success factors for dynamic capabilities from a psychodynamic perspective and creates opportunities for future research.

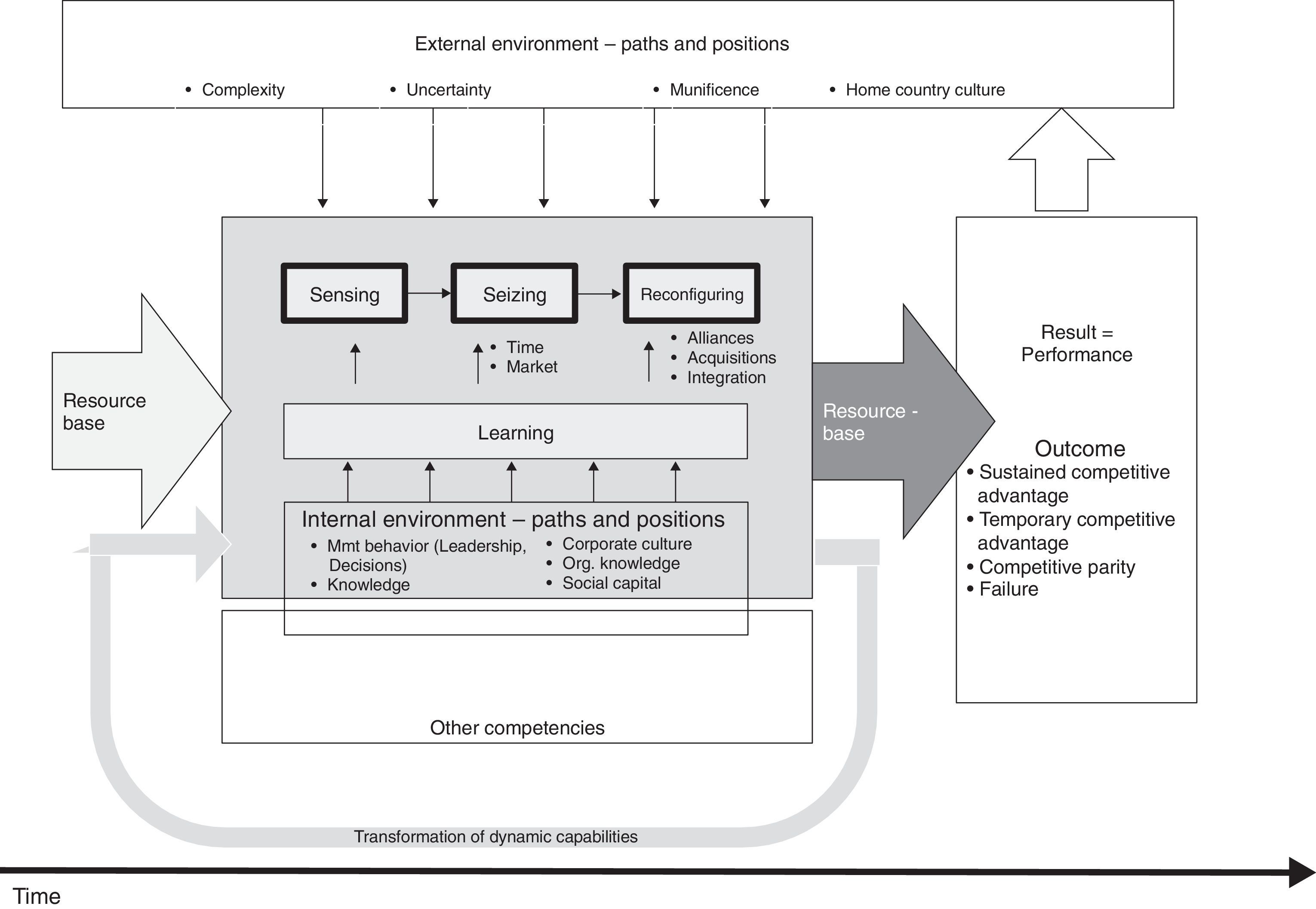

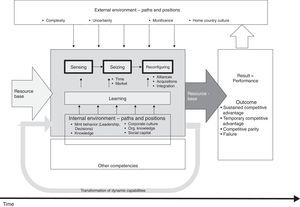

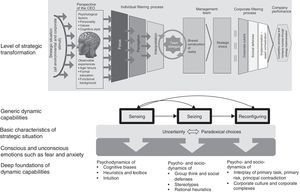

Teece, Pisano, and Shuen's (1997) theory of dynamic capabilities has received increasing attention in the last ten years, and Teece (2007) has continuously developed the original concepts. He identified three generic dynamic capabilities: sensing opportunities and threats, seizing opportunities, and reconfiguring assets and structures (Hodgkinson & Healey, 2011). The external and internal environments represent the factors that influence the sensing and seizing of the opportunities, so that the existing resource base will be re-orchestrated and reconfigured (see Fig. 1). Although the concept of dynamic capabilities is now well integrated into strategic management, two major points of criticism are still prevalent and need further exploration.

Fundamental elements of dynamic capabilities.

The first point of criticism is that a there is a fundamental paradox of continuous change versus a human and technical need for stability and a static point from which to generate the change. This paradox pervades all dynamic capabilities approaches and thus strategic management in general. It stems from the fact that processes and procedures require a fixing or specification in order for action patterns to develop, when at the same time constant change is needed, along with the willingness to create and accept it. This core paradox can be described as ‘stability versus change’ (Schreyögg & Kliesch-Eberl, 2007). Although Schreyögg & Kliesch-Eberl, and other researchers, use the term dilemma in this context, it seems more appropriate to focus on the paradoxical nature of this pair because a paradox is best described by two contradictory elements which are related to each other as the two sides of one coin, they persist and are impervious to solutions, whereas a dilemma has an either/or solution requiring a trade-off (Lewis, 2000; Smith, 2015). Stability and change seem to be contradictory, yet they are obviously both necessary for successful organisations. Stability stems from path-dependency, a certain organisational and structural inertia, as well as the need for strategic investments (Ghemawat, 1991), which are entered into to create a purposeful resource base. Investments in the resource base lead to a certain level of determination, sometimes resulting in rigidity and turning into ‘sticky resources’. Yet, in the organisational context, clients and their changing needs, technological development, changing competitors, and suppliers need change to survive and grow.

Schreyögg and Kliesch-Eberl (2007) try to solve this paradox by approaching it through the central idea of focusing on the ability of combining and connecting the resources instead of focusing on the resources themselves. They also introduce the notion of a monitoring system which Moldaschl (2006) coined as ‘institutional reflexivity’. Both share the separation of the creation of patterns from the creation of dynamics. As it will be shown later here, the paradox is and must be unsolvable when the human side of the decision maker is taken into account as the root of dynamic capabilities.

The second point of criticism is that the nature and location of dynamic capabilities is unclear. Dynamic capabilities obviously deal with capabilities and competencies, but it is not yet clear where these capabilities are ultimately located: are they structures or processes and thus competencies of the organisation, or are they competencies of individuals? Do they emerge individually or collectively, or are they simple organisational aggregations? The strategizing manager, who would be an intuitive starting point for analysis and the locus of these capabilities, was for a long time not existent in this construct, even though it was assumed to be closely tied to the field of psychology (Helfat et al., 2007). Recently, the human decision maker is receiving more attention (e.g., Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009; Felin, Foss, Heimeriks, & Madsen, 2012; Hodgkinson & Healey, 2011; Tripsas & Gavetti, 2000) and the contemporary literature on microfoundations of dynamic capabilities (e.g., Barney & Felin, 2013; Felin et al., 2012; Foss & Lindenberg, 2013; Foss, Heimeriks, Winter, & Zollo, 2012) and dynamic managerial capabilities (Helfat & Martin, 2015) is now integrating this perspective, still mostly focusing on the purely cognitive side of the manager. Only Hodgkinson (2015) and Hodgkinson and Healey (2011, 2014) take a closer look at the pure psychological and emotional underpinnings of dynamic capabilities.

In the following we analyse how both of the above-described shortcomings can be addressed by the behavioural strategy perspective as a useful complementary and explanatory construct, especially when it focuses on psychodynamics and the underlying emotions of fear and anxiety, because of their deep influences on strategic decision-making and subsequently, the resultant strategies. Thus, the goal of this paper is to explore how behavioural strategy insights can shed new light on the deep foundations of dynamic capabilities and help develop key aspects or key factors that will ensure the success of the corporation. Introducing the term deep foundations serves the purpose of underlining the psychodynamic nature of the influencing factors within and between the human strategizing manager(s) and alludes to the mostly unconscious side of these factors.

Starting with the natural observation that strategic choices are made by human beings on the C-level either individually or in a Management Team, the foundation of dynamic capabilities must be conceived within the individual, such as with the CEO and his/her Top Management Team, its actions, decisions, and interactions, to develop and implement corporate strategy with regard to competitive advantages. Consequently, we focus on psychodynamic concepts as a fairly neglected part of behavioural strategy. It will be argued that this perspective can help explain the cause of the insolvability of the fundamental paradox, depicting a basic human conflict, which will prove especially useful in the specific context of strategy making, characterised by high uncertainty. The reason is that psychodynamic theory deals with the situation of uncertainty in human decision-making and the resulting emotions, providing particular insights into the underlying basic human conflicts. Paradoxes, by nature, consist of seemingly conflicting elements. They provoke cognitive and emotional uncertainty, resulting in fear and anxiety. As a result, we offer specific starting points for the development of dynamic capabilities for management teams operating within strategic decision-making situations, to arrive at better strategic decisions and strategic management, despite the unsettling factors resulting from the paradox.

The next part introduces the connection between dynamic capabilities, microfoundations (Barney & Felin, 2013; Felin et al., 2012; Foss & Lindenberg, 2013; Foss et al., 2012), psychological foundations (Hodgkinson & Healey, 2011), and behavioural strategy (Nagel, 2014; Powell, Lovallo, & Fox, 2011). Subsequently, the psychodynamic perspective is presented, and the functioning of fear and anxiety in strategic situations, characterised by uncertainty and paradoxical choices, is described. By proposing to look at dynamic capabilities as a competency of top managers and top management teams, it narrows – but at the same time deepens – the understanding of dynamic capabilities. The three generic dynamic capabilities developed by Teece (2007) are used as a framework to apply and integrate the psychodynamics knowledge to finally make this construct applicable for practical use. It will also be demonstrated that their generic nature can be filled with psychodynamic insights, linking them differently to a number of constructs already integrated in behavioural strategy; thus, recommendations for the practitioner come within reach. At the end of the paper the conclusion examines the contribution and gives an outlook for future research.

Linking microfoundations of dynamic capabilities with behavioural strategyIn the dynamic capabilities discussion, a new stream is getting more influence: research on microfoundations and psychological foundations of dynamic capabilities. Microfoundations, often connected with dynamic managerial capabilities, explain the roots of competitive advantages. To do so they look at the origins and the nature of dynamic capabilities and how choices and interactions create structure, at the behaviour of individuals within structures, and at the role of individuals in shaping the evolution of structures over time (Barney & Felin, 2013; Chwe, 2001). Although microfoundations have generally focused on the information and expectations of singular actors making decisions on behalf of the organisation, the approach tries to also understand what emerges (Barney & Felin, 2013) from the interaction of individuals in creating competitive advantages and what can then be understood as dynamic capabilities. More cognitively oriented is the approach of dynamic managerial capabilities introduced by Adner and Helfat (2003) ‘as the key mechanism to achieve congruence between the firm's competencies and changing environmental conditions’ (Kor & Mesko, 2013, p. 233). Three core underpinnings, (1) managerial cognition, (2) managerial social capital, and (3) managerial human capital (Helfat & Martin, 2015), are researched in order to capture how the firm's set of managerial capabilities drive and how they are influenced by the unique asset base of the firm. These three managerial capital assets are linked with each other and also link the dominant logic of the firm to the ‘personal decision base’ of the manager who represents the managerial capital. The CEO is attributed a special role, resulting in the ‘CEO effect’ (Helfat & Peteraf, 2014), because s/he leads the (re)configuration of dynamic managerial capabilities within the senior executive team (Kor & Mesko, 2013), focusing on cognitive aspects of the manager as an individual or part of a team. Therefore, Helfat and Peteraf (2014, p. 835) recently introduced the concept of ‘managerial cognitive capability’, which they define as “the capacity of an individual manager to perform one or more of the mental activities that comprise cognition.” As managerial cognitive capabilities for sensing, they propose perception and attention, for seizing they suggest problem-solving and reasoning, whereas reconfiguring is based on language and communication skills as well as on social cognition (Helfat & Peteraf, 2014).

By developing an understanding of the psychological foundations of dynamic managerial capabilities, Hodgkinson and Healey (2011) apply social cognitive neuroscience and neuro-economic research results to dynamic capabilities, to establish an understanding of the cognitive and emotional capacities of the managers who are seen as being responsible for creating enterprise performance. Helfat and Martin (2015) consider psychological foundations as a subgroup of dynamic managerial capabilities, whereas Hodgkinson and Healey (2011) describe them as part of microfoundations. This small disparity demonstrates well that the lines between these different concepts are still rather blurry and seem to depend on the researchers’ perspective (economics versus psychology).

These descriptions of microfoundations or dynamic managerial capabilities remain in the abstract, giving no practical advice about what a corporation or individual needs to do to create and establish superior dynamic capabilities or develop superior competitive advantages. This might be because capabilities are explained by their outcomes, and without any specific quality, such as when Helfat and Peteraf (2014) describe the need for sensing through more generic descriptive definitions from the APA for perception and attention. Similarly, attention to change is abstractly described so as to facilitate the change (Helfat & Martin, 2015). Therefore, managers will find it difficult to implement the concept to improve their dynamic capabilities.

Because behavioural strategy concentrates on the human aspects – the shortcomings and resources of the decision makers within strategic management – it might provide an answer to how dynamic capabilities may be improved. It concerns itself with the psychology of the strategic decision maker and his or her typical reactive or behavioural patterns that affect the quality of the decision-making and thereby influence the short- and long-term success of the firm. According to Powell et al. (2011), behavioural strategy merges cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and social psychology with strategic management theory and practice, so that realistic and concrete assumptions about the interplay of human emotions, cognition, and social behaviour with corporate strategic management result. Behavioural strategy should focus on both conscious and unconscious psychologically relevant aspects of strategic decision-making (Nagel, 2014) to allow for a better understanding of the psychological foundations of dynamic capabilities so that clear directions for practical improvements can be seen.

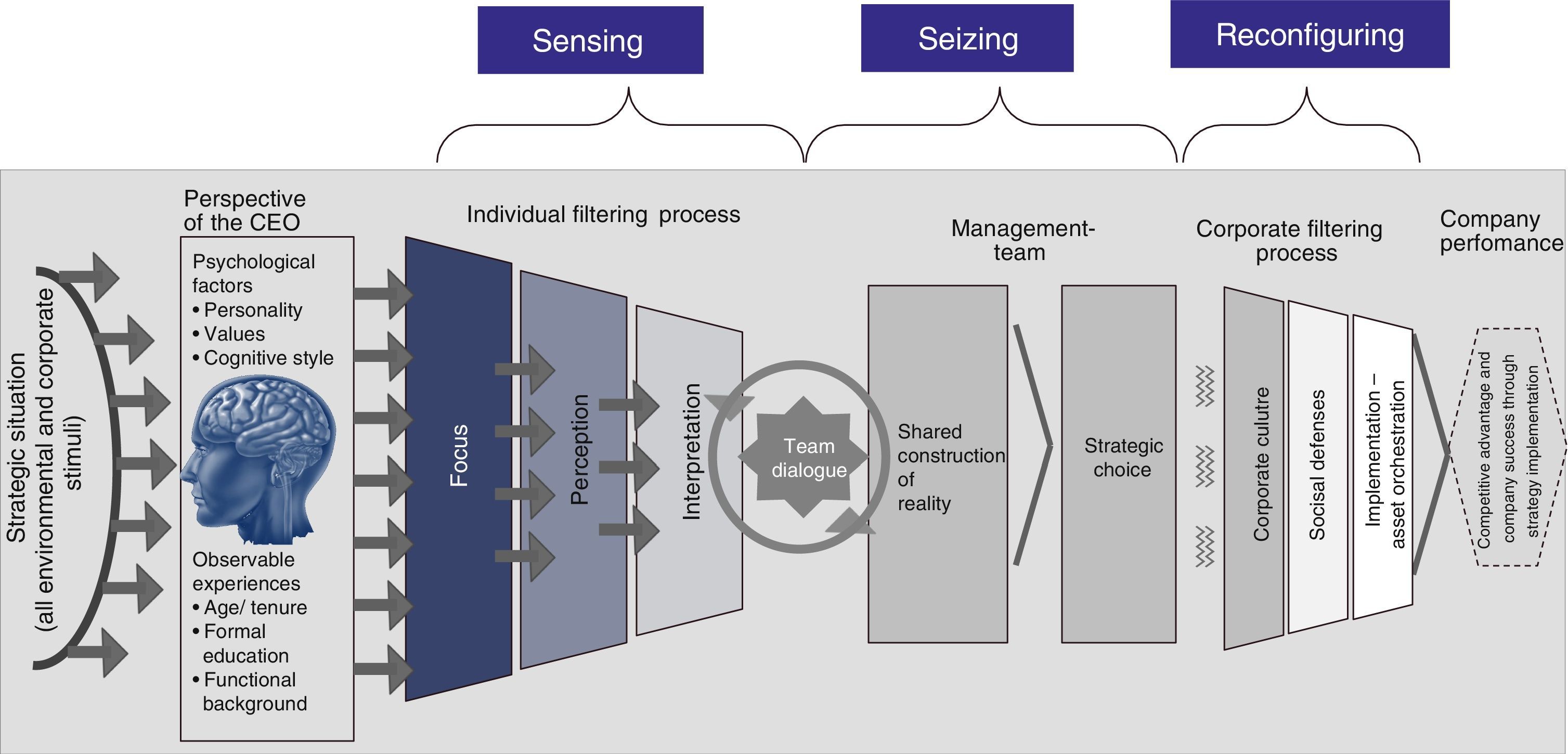

Integration of behavioural strategy with the psychological foundations of dynamic capabilitiesWhen describing strategic behaviour, three conceptual elements are needed: strategic situation, strategic choice, and the results of these. Finkelstein, Hambrick, and Cannella (2009) provide a first realistic model of ‘strategic choice under bounded rationality’ (p. 45) while integrating these conceptual elements and executives’ psychological boundaries. Linking strategic situation with strategic choice and organisational performance provides the basic steps of a strategic (transformation) process, which starts with perception of the strategic situation and shall lead to achieving competitive advantage and organisational performance, after a strategic choice and implementing that choice. Each of these steps corresponds with a generic dynamic capability in Teece's (2007) model, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

The psychology of the strategic transformation process.

In an ideal world, the strategy process starts (1) with a CEO who reacts in his/her individual way to the strategic situation of the corporation and to the actual set of strategically relevant stimuli. His/her perceptions are processed for assessment through a personal filter system as s/he senses them, and the perceptions result in a subjective interpretation of the company's strategic world. This sensing (capability and process) ideally leads to (2) a dialogue in the top management team,1 where each of that team's members will have constructed her/his own view of the strategic world. Thus, in an intense dialogue, the management team should come to a shared perception and construction of the assumed strategic reality. This prepares the ground for developing strategic alternatives and for together, seizing one of them. After choosing the strategic option and a strategy, implementation should take place (3) through a process of asset orchestration by creating, extending, upgrading and protecting the enterprise's unique asset base (Teece, 2007, p. 1319) This asset orchestration – according to Teece (2007) management functions as an orchestra conductor, whilst the assets/instruments are not only newly combined, but are themselves constantly being created, renovated, and/or replaced – also undergoes a filtering process on the corporate level, influenced by corporate culture and social defence mechanisms. At the end, a competitive advantage is created, leading to corporate performance.

Each of the generic capabilities of sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring is at the same time also a procedural piece of the larger process of strategy creation, influenced by psychological aspects on the individual, team, and organisational levels among those implementing the developed strategy. Behavioural strategy provides the psychological foundations for this strategy making. Focusing on psychodynamics allows for understanding how dealing with an uncertain future generates specific (mostly unconscious) emotional and behavioural reactions. Consequently, here we talk about what is coined as the deep foundations of dynamic capabilities.

Integration of psychodynamic behavioural strategy findings and dynamic capabilities, or deep foundations, shall be carried out in two steps in the next sections. Following Teece's capabilities model (Teece, 2007) and the link with the proposed strategic transformation process model, it will be firstly shown that on each process step, or for each generic dynamic capability (here in the proposed sense) specific insights of behavioural strategy can be successfully applied and integrated to gain a deeper understanding of them. If knowledge of these deep foundations does not become an active part of dynamic capabilities in the form of management competencies and insight, strategic decisions will risk obstructive distractions resulting in inadequate decision-making. Secondly, corresponding success factors can be derived from this in-depth exploration, which are the founding aspects of dynamic capabilities and which help make this construct more approachable and applicable in practical strategic management.

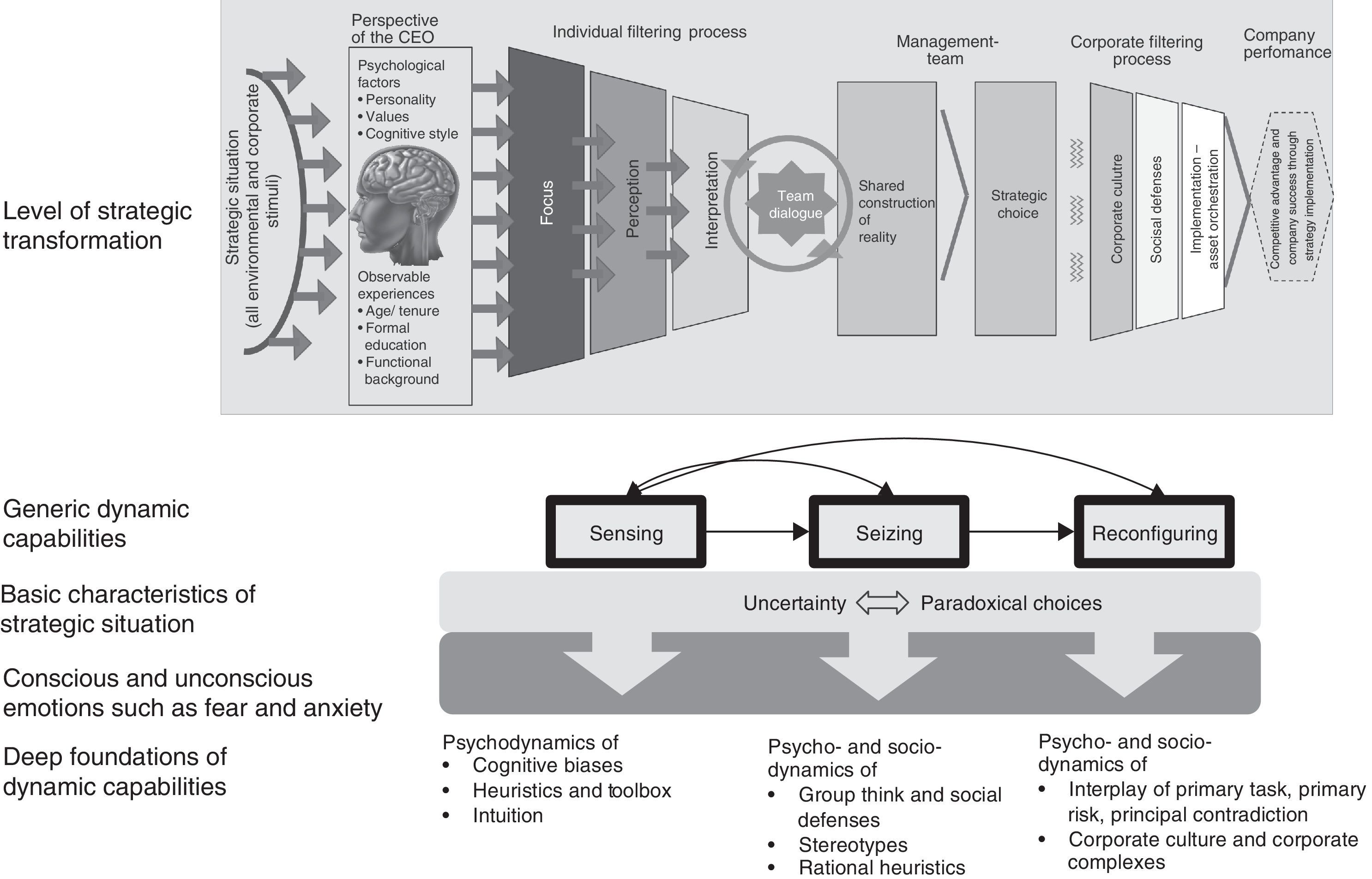

The rest of the article takes a closer look at each of the three process-steps (sensing, seizing, reconfiguring) to demonstrate how behavioural strategy insights can enhance their understanding. A first overview of these influencing factors is given in Fig. 3. It connects the generic dynamic capabilities with the strategic transformation process (see Fig. 2) and the underlying psychodynamic relevant factors – these deep foundations – that influence each step and each generic dynamic capability.

The process perspective starts with the sensing individual, continues with the seizing on top management team level and ends with reconfiguring on the organisational level. This implies that factors influencing the individual also affect the next two strategy-making levels and process steps. In addition, factors influencing the top team process also exert their impact in work groups and on the corporate level. So the model comprises a time horizon as well as levels from individual to corporate, together with the notion of generic dynamic capabilities. Although these elements, levels, and steps are closely intertwined, it is shown that influencing psychodynamic factors can be specifically attributed to each of them.

Deep foundations – the basic role of fear and anxiety in strategic decision-makingIt is common sense that emotions play a significant role in human decision-making, yet in strategic decision-making the influence of emotions, especially negative emotions such as fear and anxiety, is still taboo. Hitherto, there has been strong evidence from psychoanalytic research that situations characterised by uncertainty and paradoxical conflicts give rise to a very specific set of emotional and behavioural human reactions surrounding fear and anxiety. As uncertainty and paradox are characteristics of strategic problems, the assumption that fear and anxiety play significant roles in strategic decision-making is not far-fetched.

The influencing factors on the decision-making individual can be approached from two sides: from the outside as characteristics of a strategic situation and from the inside as a human being's specific reaction to a specific situation. The advantage of using psychodynamic concepts is to provide a link between the outer and the inner worlds of the individual (and the group), allowing for psychological explanations, helping to understand the deep foundations of dynamic capabilities.

Starting with the outside world, the sum of the complex characteristics of strategic decisions (differentiated from other types such as economic) can be best described by a very high level of uncertainty. Uncertainty may consist of not knowing: (1) who is or will be the competition and how will they react; (2) how to seize new and partly unknown possibilities; (3) how heterogeneous possibilities compare so a decision can be made; (4) whether or not the strategic path will be successful (predictability of success is usually low), and; (5) because the territory is unknown, the management team may lack of experience specific to the situation at hand (Bingham & Eisenhardt, 2011; Nagel, 2014).

Fear, anxiety and uncertaintyA high level of uncertainty, especially ambiguity, triggers two central reactions in human beings: fear and the desire for control (Gilbert, 2006; Hüther, 2005). In general, fear2 is triggered by outer or inner threats and induces actions such as attack, defence (fight), or retreat (flight). These threats can be real or perceived risks to physical, existential, or emotional intactness. In the context of business, physical attacks do not play a significant role, but existential and emotional intactness are important. Both deal in some ways with self-esteem and thus identity. Existential threats can be money, home, and clothing and might also have a physical impact at the end, whereas emotional threats are more difficult to define. In particular, uncertainty – not knowing what the future brings – can be perceived as a threat. Up until a certain level of difference between the learnt and the new, human beings react with curiosity and wish for exploration. Yet, when that difference increases to a certain point, the first reactions are retreat and abandoning, which can subsequently lead to existential fear, loss of acting capability, and loss of control (Holzkamp-Osterkamp, 1975). Fear, especially existential fear, caused by facing long-term company failure and the need for strategic change, is likely for top managers in the process of strategy making.

Certain cognitive intra-psychic mechanisms exist to reduce fear for the individual: an human can use emotional suppression, redirection of attention, cognitive reinterpretation, and also reappraisal (Hartley & Phelps, 2012). Other conscious cognitive fear-reducing mechanisms are searching for, applying, and verifying already tried-and-tested solutions, and reflection on the conscious emotional level. Fear also has a lot to do with social relationships, such that positive feelings can also be induced through the presence of a close person, which results in fear reduction (Hüther, 2005).

Fear, anxiety and the paradoxical nature of the basic human dilemmaFrom a psychodynamic perspective, fear and anxiety are under specific individual circumstances handled unconsciously and result in the avoidance of the hidden inner conflict through repressing, forgetting (Mentzos, 2009), and other ego defences (Freud, 1936). The psychodynamic theory, mainly based on Sigmund Freud (psychoanalysis) and Carl Gustav Jung (analytical psychology) and their followers over the last one hundred years, focuses on human inner emotional life and tries to understand its conscious and unconscious reactions to the outer and the inner world. It assumes the human being is naturally born into dialectical tensions, especially the basic tension of autonomy versus attachment, which drives and motivates all humans. This bipolar tension seems to be antithetic, consisting of two ostensibly oppositional and contradictory poles – yet integration of these oppositions over the course of individual personality development and life creates renewal, dynamics, and differentiation, as well as progress, which was coined as individuation process by C.G. Jung.

In psychodynamic theory these two poles represent an intra-psychic conflict between self-related tendencies and object-related tendencies. Self-related tendencies are the need for autonomy, identity, independence, and autarky, whereas object-related tendencies are towards attachment, commitment, containment, and solidarity. Intra-psychic conflicts lead to feelings of unpleasant inner tensions because realizing one side of the conflict would induce giving up the other side which itself results in the experience of danger and the subsequent feeling of anxiety. Schad, Lewis, Raisch, and Smith (2016, p. 10) speak in this context of the ‘angst of tensions’. In the intra-psychic world of an individual, anxiety has the same signalling function as external physical threats. Therefore, despite the outmoded Freudian assumption that anxiety is a basic drive, it is now common knowledge that anxiety represents one of the central axes of psychodynamics and psychopathology (Mentzos, 2009).

Normally, this basic human dilemma is continuously resolved, balanced, and integrated over the course of the lifespan in a dynamic process so that progress appears through developing a new, third position in which both former opposing aspects are integrated without giving up one of them. Because of its threatening and pain-causing nature, blockages or rigid, one-sided reactions can happen and might result in psychological disorders because an underlying fear cannot be managed and solved by the individual. Psychodynamic theory assumes that neurotic psychic disorders are based on this unresolved conflict on a specific stage of psychic development linked with a specific fear. So, behind every neurotic development lies a fear connected with a specific form of this basic dilemma or conflict (e.g., Mentzos, 2009).

Instead of naming this basic tension a ‘dilemma’ and following Lewis (2000), one can understand it as a paradox. Jung himself did so when coining the term of the Self (with capital s), integrating the conscious and the unconscious human being, its wholeness and fragmentation, under one basic archetypal roof (Jung, 1944/1995, §20). For him the process of integrating the paradoxical natures of the autonomous unconscious with individual consciousness is a life-long process of a stepwise development and individuation (Jung, 1944/1995, 12, § 59ff). Jung was strongly influenced by eastern tradition and philosophy and used their conception of wholeness and integration as basic underlying principle of his Analytical psychology. So as Schad et al. (2016) summarise similar to Lewis (2000), in following ancient eastern and western philosophical traditions, a paradox is characterised by a tension of opposites and is defined by persistent contradiction of interdependent elements. Scholars thus distinguish paradoxes from dilemmas because paradoxes persist, being impervious to resolution, whereas dilemmas can be resolved with either/or decisions requiring a trade-off (Smith, 2015), yet these concepts overlap, choosing a different time horizon for example (Smith & Lewis, 2011). In management science the paradoxical lens has been applied in the search for explaining organisational phenomena based on contradictory-yet-interdependent elements (Schad et al., 2016).

The core paradox of stability and change, discussed here for dynamic capabilities, is one of the researched paradoxes (others are: e.g., profits vs purpose, exploration vs exploitation, cooperation vs competition, novelty vs usefulness, see Schad et al., 2016) as it is part of this basic psychological ‘paradox-family’. All paradoxes derive from the continuous world formula of ‘stirb und werde’ (die and become) as Goethe described in his poem ‘Blessed Yearning’, being part of the famous west-eastern Divan. Already there his lyrical I tells us that this paradox has to be lived through, worked through, and integrated until life ends. Despite the beautiful lyrical solution, the human being has the tendency to react with the psychic defence mechanism of reducing the alleged emotional pain of conflict and choosing. This impacts the strategy process on all three levels discussed here.

Effects of deep foundations in the process of strategy makingFirst step – the individual level of the decision-making process and the role of uncertainty and paradoxesWhereas behavioural strategy research focuses on the distorting role of cognitive biases and rules of thumb, the underlying psychodynamics are rarely touched upon. Due to the characteristics of the strategic situation consisting of uncertainty and paradoxes, emotions such as fear and inner conflict play a central role in strategic decision-making and influence the perception of the individual strategizing manager.

Anxiety and fear are taboo subjects in management (Nagel, 2014), although they are natural biological reactions to situations of uncertainty. A typical reaction to uncertainty in management is exerting control – which is understood as being part of a manager's role. Yet, in the making of strategy, strategic planning often overruns strategic thinking, which represents a first, common, and institutionalised defensive reaction to pain- and fear-causing uncertainty. Certainly, this occurs because they are closely linked in the brain, as neuroscientific research explains: in the frontal lobe of the brain, the area of perceiving anxiety and fear as a feeling (a conscious process) is connected with the area responsible for planning-competence. The human being needs to have the feeling of being in control, lest helplessness, anxiety and depression result (Gilbert, 2006). Managers are a good example of the need for control when facing uncertainty; their way of dealing with this fear is to implement controlling and planning measures, often linked with a personal tightly clocked schedule, not leaving any space for development or experience of fear and anxiety. These planning and controlling measures create the illusion of being in control of the situation; they reduce the underlying fear, make the manager capable of action (the mantra of the manager is to take action) and seem to help ensure economic success.

Choices, paradoxes and defencesStrategic choices entail by nature a conflict and the emotional necessity of finding a solution for the outer (maybe even inner) conflict. Conflicts are inherent in strategy making because strategic decisions always entail choosing between conflicting alternatives. Integrating the link between strategic decision-making with uncertainty and conflicting choices, emotions such as fear play an important role in strategic decision-making and influence dynamic capabilities. Therefore, it is a necessary ingredient of dynamic capabilities to understand how fear can be read, understood, integrated, or even reduced in a strategic decision-making process.

Paradox is part of strategic choices. With increasing technological change, globalisation and diversity disruptions appear and expose tensions which reveal paradoxes on all levels – individual, team, and organisation – concerning learning and transformation, communication and belonging and organising structures (Lewis, 2000). Because inherent conflicts cause the same psychic pain as uncertainty, or strategic choice, the psychic reactions are also the same.

One way of dealing with fear and paradoxical choices that induce fear are unconscious defence mechanisms. Defence mechanisms are intrapsychic operations that keep unpleasant emotions, affects, and perceptions away from the conscious mind (Mentzos, 2003). Because fear and anxiety are often taboo in the context of management, repressing and forgetting as psychic defences are the second most common reactions, after controlling and planning.

If negatively connoted feelings are suppressed, unfortunately they may not display their signalling function, which is a human feature proven by evolution (Hüther, 2005). Moreover, this has side effects not only on the repressing individual itself but also on his/her respective company. If the feeling of fear is suppressed, not only the individual, but also the company cannot react appropriately to the external threats causing this fear. These external threats can be, for example, changing market conditions caused by a new competitor. Suppressed fear then might induce overestimation of the company's own market position and underestimation of the power and success of the new entrant, leading to delayed innovation efforts. Other defence mechanisms are more complex and need more detailed psychoanalytic knowledge to decipher their existence and their meaning.

According to Mentzos (2009), building on Anna Freud's (1936) seminal work on defence mechanisms, five levels can currently be differentiated. On the first and very immature level, defence mechanisms work around psychotic reactions such as psychotic projections. They are not very common in a normal business environment. Yet, the next level is more prevalent: non-psychotic splitting, where the world is split into good and bad, us and they, e.g., the competitor being seen as ‘the evil enemy to combat’, or projections, where unwanted or repressed shadow aspects are projected on to another entity. Projective identification might appear in the boardroom and pose a problem, when out of fear and anxiety the personal needs for grandiosity of one board member are projected so strongly onto the CEO, for example, that s/he starts to identify with the projection and feels like a corporate hero or grandiose rescuer.

On the third, more mature level, intellectualising, rationalising, and affect isolation are defence mechanisms serving the suppression of emotional aspects to concentrate only on the cognitive and rational aspects – very common defence mechanisms in management. Forgetting, denying, and deferment are also widespread. On the fourth level, mature defence mechanisms such as humour and sublimation (e.g., creating a piece of cultural participation such as art or literature, or engaging in a conversation around that) are part of the active coping with difficult emotional situations, threatening tensions and anxiety and fear. All these defence mechanisms happen to work on an intrapsychic level. However, all of them can also arise on an intersectional level within teams, groups, or larger social systems. They then represent the fifth level of defence mechanisms and are analysed in the next section under the notion of social defence mechanisms.

Typical for the perception stage as the first step of the strategy process and as part of the stability-change paradox, is the basic polarity of old versus new which Lewis (2000) categorises as a paradox of learning. It evolves around sense making, innovation and transformation. According to her research, defences of repression, projection, and regression are very common, resulting in cognitive self-reference, inertial actions, and simplifications of values, structures, and systems.

Paradoxes often develop a vicious dynamic because the more the manager wants to resolve the paradoxical tension by choosing one side of the coin (such as wanting to achieve change), the more the other side of the coin creeps through the back door into the forefront as holding on to the past (Lewis, 2000). This is a typical neurotic reaction to the incapacity of holding the emotional tension and integrating the polarities – the more one side is rejected or suppressed, the more it pops up at unexpected moments.

As the word defences illustrates, there exists a non-defensive way of dealing with fear and anxiety resulting from strategic choices and paradoxical situations. It happens on two levels within the individual: (1) actively dealing with the emotions turning into the personal reasons for the perceived anxiety, and; (2) cognitively understanding and dealing with the conflicting elements of choice.

Dealing with emotions can best be described as holding the tension instead of avoiding it. It demands high emotional maturity and the capacity to undergo a personal quest for the anxiety-provoking aspects of this strategic choice situation, associations accompanying the strategic choice and expected results and outcomes. What exactly it is that provokes these feelings must be explored. The difficulty here is to detect and admit one's own defences. A self-experienced manager can handle this intrapsychic personal process alone, but for most managers it is difficult to deal with the unknown territory of anxiety and fear; the initial support of a third, psychoanalytically trained person can help develop a deeper and clearer picture of the anxiety-causing strategic landscape and paradoxes within it.

On the cognitive level – which must be supported by the emotional capacity of holding the tension, – paradoxical thinking is the ability to juxtapose, explore, and integrate contradictions in actively thinking these opposites or antithetical ideas are equally true. For Rothenberg (1979), this is not only a common trait of creative geniuses but also the basic source for creative innovations (Ingram, Lewis, Barton, & Gartner, 2016). As researchers suggest managing paradoxes can be attained through the interlinked capacities of (1) accepting, (2) accommodating or confronting, (3) differentiating/integrating (Lewis, 2000; Smith, 2015), and (4) transcending (Lewis, 2000).

Accepting paradoxes means ‘learning to live with the paradox’ (Lewis, 2000, p. 764) and working it through. ‘Accommodation involves defining a novel creative synergy that addresses both oppositional elements together’ (Smith, 2015, p. 60). Confronting consists of discussing the tensions, the logic and the concerns, and also using humour (Lewis, 2000). Differentiating includes the separation of distinct elements and the honouring of their differences, whereas integrating involves creating linkages and synergies (Smith & Tushman, 2005 in Smith, 2015). Transcendence represents the capacity to think paradoxically (Lewis, 2000), as paradoxical thinking techniques such as ‘janusian thinking’ consist of creatively and simultaneously formulating antithetical elements so that something new, a real third position, develops creatively, transcending the ordinary logic (Lewis, 2000; Rothenberg, 1979; Schad et al., 2016). For all human beings – in strategy or in ordinary life – the task of life is to continuously progress through balancing, integrating, and creating new possibilities as a possible third position. The dialectical tension and its inherent ambivalence can thus only be experienced consciously so that a creative new way of dealing with the ambivalent situation will appear.

Cognitive biases as defenceStrategic and paradoxical thinking does not take place in a logical or rational way. Yet, rationality still seems to be the basic feature of the human being in decision processes, as the cognitive biases literature suggests. Management research understands cognitive biases as the result of irrational choices (e.g., Kahneman, 2003); therefore, they are intensely discussed in the related fields of behavioural strategy such as behavioural finance and behavioural economics. They even seem to be the major focus of the B(ehavioural)-part in these fields recurring in the rather outdated idea of behaviouristic approaches in psychology. Although Gigerenzer (2007) has demonstrated the effective and helpful role cognitive biases can play and how they develop their own rationality by applying hidden rules to unspecific situations so that faster decisions become possible (Gigerenzer, 2007; Nagel, 2014), cognitive biases are still understood as fallacies, irrationalities, and a result of poor thinking.

As already described, negative emotions in general cause feelings of discomfort, which human beings are mostly prone to avoid. The area in the brain responsible for avoiding unpleasant feelings differs from the area seeking pleasure and lust. The amygdala processes these feelings of discomfort, which are closely tied to feelings of being threatened and in danger (Roth, 2008). So, a feeling of psychic discomfort results from information threatening the individual's concept of the world. Avoiding this threat leads to the so-called ‘ostrich effect’ (Hodgkinson & Healey, 2011; Karlsson, Loewenstein, & Seppi, 2009), where managers do not want to see, for example, a changing market condition challenging the actual business model. The ostrich effect is part of the cognitive biases list and demonstrates that fear and anxiety are linked to biases.

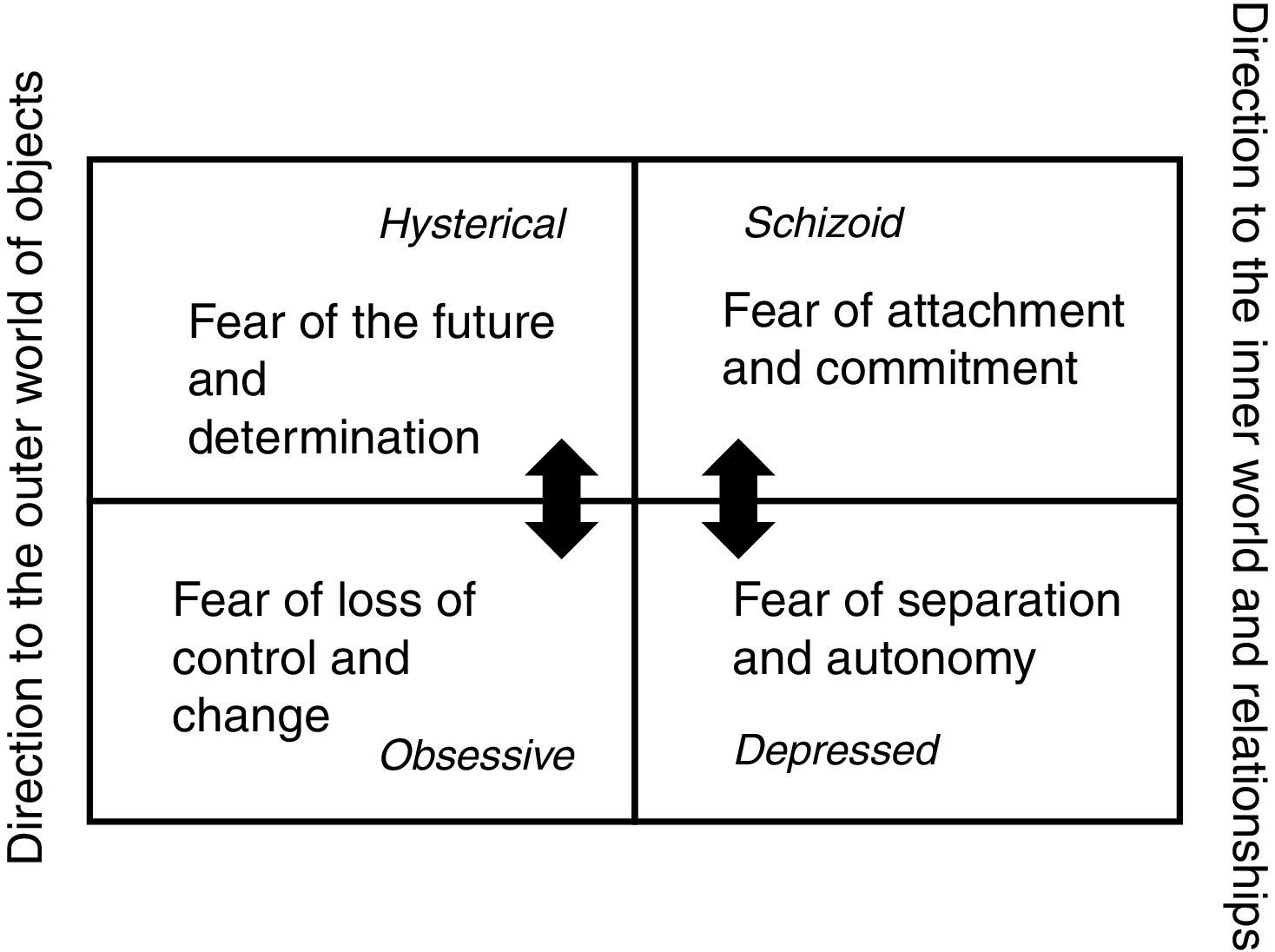

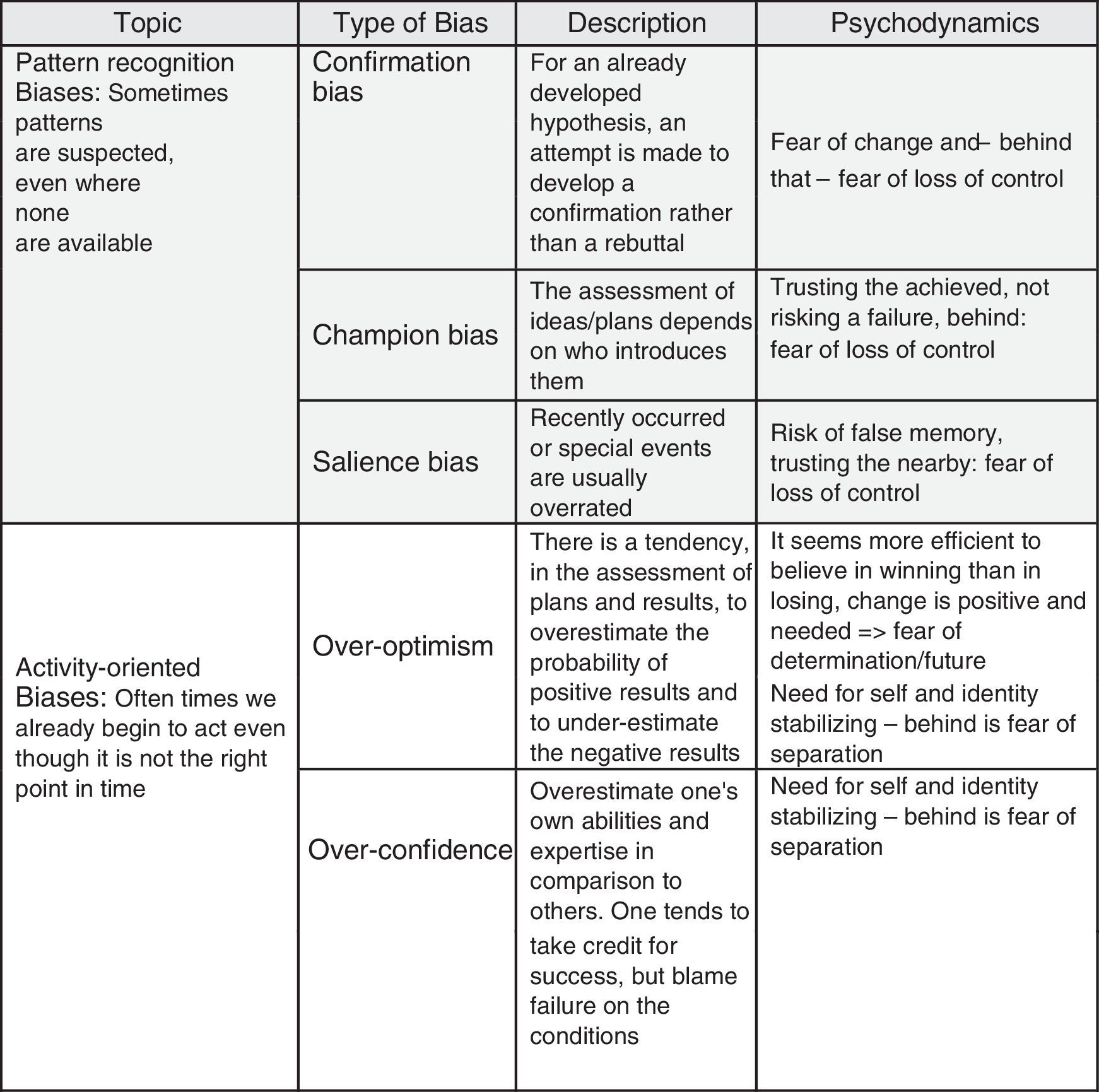

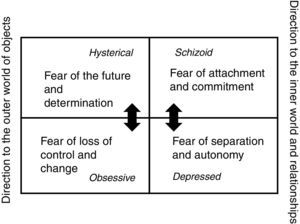

From a psychodynamic perspective it is very obvious that fear and uncertainty play an important, yet previously unresearched, role in the development of cognitive biases that might explain their nature from a different standpoint. In developing a first overview of the most important biases with regard to strategic decision-making, linking them with possible anxiety structures, Riemann's four different types of anxiety (1961) provide a framework for structuring different basic types of anxiety, linking them with personality types (in italics; see Fig. 4).

Depending on the direction (outer or inner world) and the nature (fear of loss or fear of determination), four different kinds of fear can be categorised into four types, which are each connected with a prevalent personality type. The two fears directed to the outer world and prevalent in the hysteric or obsessive personality type lead to more (hysteric with the fear of determination and the need for constant change) or less (obsessive with the fear of change and the need for constant control) risky decisions. Fear of attachment (and the need for independency of other people) and fear of separation (with the need for closeness to other people), directed to the inner emotional world and relationships, affects the readiness to integrate others into the decision-making process (depressive) or deciding alone (schizoid). In each healthy human being, naturally all four types of anxiety and fear can be found, but depending on the underlying personality structure one type is more dominant than the others. The level of anxiety explains the differences between nonpathological over neurotic to pathological traits.

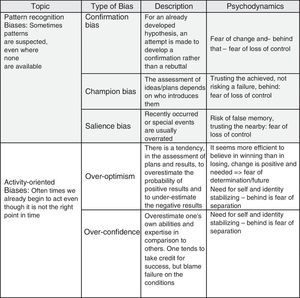

Biases are often understood as shortcuts in thinking, yet from a psychodynamic perspective they can be understood as psychic defence mechanisms against threatening feelings of anxiety and fear. By using now the four basic types of anxiety, I will provide a first attempt to understand the psychodynamic mechanisms, working in the background of the bias. Fig. 5 provides an overview of this attempt, which is supported by existing research results, such as that some of the cognitive biases are openly linked with fear; for example, fear of loss can result in ambiguity aversion or preference for a known versus unknown risk (Ellsberg-Paradox; Frey & Benz, 2001; Loewenstein, Rick, & Cohen, 2008). It was also found out that anxiety increases attention to negative choice options, the likelihood that ambiguous options will be interpreted negatively, and the tendency to avoid potential negative outcomes – even at the cost of missing potential gains (loss aversion and framing effects, see Hartley & Phelps, 2012).

Selective strategically relevant cognitive biases and psychodynamics.

Although some basic patterns regarding the types of anxiety behind the biases become visible, it also becomes clear that some biases are seemingly more complex than others and might be provoked by more than one type of anxiety. The anxiety patterns can be described in these ways: (1) pattern recognition biases and stability biases support stability and are based on the fear of change and the accompanying fear of loss of control, whereas; (2) activity-oriented biases rather strive for change, and their underlying fear is the fear of determination – these are also connected to self-stabilizing needs and the fear of separation, which entails the belonging to a socially relevant group; (3) social biases are by nature also closely connected to relationship-oriented fears, the need for belonging, and the fear of separation, whereas; (4) interest biases can be induced by both fears, fear of attachment and of separation, depending on the decision-maker's personality. These first categorising attempts only provide a new understanding of biases and the anxieties in which they are rooted, but they need more research to be confirmed and refined.

Fear, heuristics and intuitionWhereas cognitive biases are common and prevalent in every decision maker and probably are present most of the time, personal heuristics are individual rules of thumb and are developed over the course of a lifetime. They depend on the biography of the decision maker, his/her personality, personal experiences and their processing, and their task is to enable quick decisions (Gigerenzer, 2007). In the management context, Madique (2011) refers to them as the ‘Leader's toolbox’, which develops over the course of a manager's life and is basically characterised by the manager's need to make decisions quickly and take swift actions (Mintzberg, 2007). Managers therefore develop personal heuristics deriving from their experiences and enabling them to routinely complete recurring tasks and quickly diagnose new ideas and topics. These personal rules are very often unconscious (Madique, 2011) and interfere with long-term strategic decision-making. They can consist of simple rules such as ‘be the best at whatever you do’, or more complex and emotional rules such as ‘if a person is not honest and trustworthy, the rest does not matter’, or practical tactical rules like ‘before expanding into a new country we use trade representatives for two years,’ (Madique, 2011 p. 2). Some rules might be valid for one industry but not for another, so the ability to differentiate between the need for application of personal rules of thumb or the need for a new thinking process is an important element of dynamic capabilities, because personal rules of thumb can be helpful in some moments, but damaging in others. This presupposes the capacity to know one's own rules of thumb and to differentiate between personal rules of thumb and intuition (Madique, 2011).

Intimate rules of thumb that are even more hidden in the unconscious. Although they habitually stay unnoticed, they play an important role in decision-making (Bowlby, 2008). They are based on emotional relationships, especially on attachment relationships. Negative emotions (fear, anxiety) play an important role, not only for the individual development of social-interaction patterns (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991; Grossmann & Grossmann, 2004) by creating internal working models (Bowlby, 2008), but also for the development of different characteristics of openness, readiness and sensibility to negative stress- and anxiety-inducing events (Hüther, 2005). Each adult has thus developed her/his specific decision-making style based on early childhood experience. Personal rules of thumb such as ‘I want to prove my father that I am the better entrepreneur’ or ‘nobody is allowed to deceive me; I will always take revenge’ can develop out of early emotional experiences with attachment figures. This reaction is linked to the creation of somatic markers that connect emotions with experiences and therewith manage perception and thinking (Damasio, 1999). They influence all decision-making processes but remain mostly unconscious because they are deeply engrained in the whole body-mind system. Somatic markers especially have an influence on decisions by the feelings going along with the mental image of the result of a strategic decision. Research proves that these feelings seem to be more important than the expected utility of the result. When mental images connected with a strategic choice entail more negative emotions (e.g., laying off people) than positive ones (because of a beautiful new product), the strategy will be introduced with less engagement and energy because of the prevailing discomfort (Hodgkinson & Healey, 2011).

Very often, when CEOs are asked why they made a particular decision, they respond with ‘gut-feeling’ or ‘intuition’ and rarely allude to rules of thumb. Yet, Madique (2011) found out that behind the so-called intuition there was often a set of rules of thumb. So the question is whether there is a difference between rules of thumb and gut feeling or ‘intuition’.

In management research, intuition has been on the agenda starting with Barnard (1938) as part of the Human Relations School (Freedman, 2013), looking at logical and nonlogical processes, the latter grounded in knowledge and experience (Akinci & Sadler-Smith, 2012). From the psychodynamic side, Jung, a contemporary of Barnard, introduced his psychological types with four basic psychological functions: thinking, feeling, sensing, and intuiting. For him, intuition belongs to the so-called irrational functions (rational in his language means reasonable judgement; judging is the attitude behind, whereas irrational stands for the focus of the individual on perception that is not subject to judgement but just happens to happen by appearance) and is, as opposed to sensing, which represents the experience of the outer world via the four senses, the unconscious perception of outer objects. Is consists not only of gazing at something, but is by nature a creative and active act, leading to conscious insights influencing actions and behaviours (Jung, 1921/1995 § 610f.).

Intuition was then more or less integrated into the heuristics and biases research programme and looked at from the dual-process-theories of cognition. They have in common the notion that there are two contrasting systems or modes of information processing (Akinci & Sadler-Smith, 2012). In all of the reviewed approaches, one part or one process of the brain functioning is responsible for processing large amounts of information beyond consciousness and uses mechanisms of pattern recognition and intuition mostly run beyond the boundaries of consciousness (Gigerenzer, 2007), whereas another part or process is responsible for a more active, deliberative and slower thinking.

Within the behavioural strategy framework, the concept of the c-system (reflective, logical) versus the x-systems (reflexive, affective) developed by Hodgkinson and Healey (2011, 2014) seems to rule the discussion. Dane and Pratt (2007) developed a widely accepted definition of intuition as ‘affectively charged judgments that arise through rapid, nonconscious and holistic associations’. They not only reintroduce affect into the concept of the former cold cognition-based intuition construct, but also define different types of intuition, depending on the nature of associations: problem-solving, creative, and moral intuitions. The nature of the moral intuition is linked to social and cultural influences, eliciting an affective response without conscious awareness (Haidt, 2001). The emerging stream of ‘intuitive-expertise’ research focusses on the expertise and knowledge of the decision maker (for a detailed overview of actual intuition research see Akinci & Sadler-Smith, 2012).

Although intuition is affectively charged and affect and emotions are an integral part of intuition (Dane & Pratt, 2007), it is not emotional and can be negatively impacted by emotions such as fear, anxiety, pride of authorship and wishful thinking (Kathri & Ng, 2000; Ray & Myers, 1989). In preparing for a decision, intuition directs attention to external strategic stimuli, categorised later as opportunities and threats. Charging with affect here means for example also that discomforting information, which is not unlikely to come up in a strategically challenging situation, can then often be rejected because it emotionally threatens self-esteem and self-identity and can be connected with fear and anxiety.

Altogether, intuition influences decision makers, especially in uncertain environments, where they draw on experiences and insights from the past in an emotionally charged manner to either come to a judgement and subsequent decision or to develop a creative new solution. Yet, intuition needs two prerequisites to contribute positively to strategic decision-making – expertise and space.

First and foremost, intuition, because it is experience based, is connected with the past and accumulated expertise over time. A decision that is very far away from the experiences of the strategizing manager should not be based on intuition only – the risk of confusing intuition with invalid rules of thumb or a simplifying judgement due to anxiety constraints, is high. Second, intuition only flourishes when it is valued and receives attention and mental space. Only then, creative solutions get the psychic energy they need to develop (e.g., Vaughan, 1989). Because intuiting is experience based, it is very personal and very different from manager to manager. There is no ‘right’ or ‘correct’ intuition. This implies that complex strategic situations require intuitive judgements of an array of top managers. Therefore, Hodgkinson and Healey (2014) propose ‘discrete innovation teams’.

Self-reflection as core dynamic capabilityIn summary, the psychodynamics of anxiety and fear influence individual strategic thinking as they result from cognitive and emotional uncertainty due to unforeseeable future and the nature of paradoxical choices. Through cognitive biases, heuristics, and intuitive reasoning, they invade our thinking and decision-making – mostly in a limiting inability to see the whole strategic situation. Therefore, it is essential for the manager to be capable of knowing about and assessing these influences.

The emotional tensions of the uncertainty of the strategic situation and paradoxical choices can be made fruitful for the organisation when the strategizing manager is self-reflective, emotionally and cognitively capable of managing this tension, and receptive to intuitive judgments based on extensive expertise and experience, and when he/she comes up with creative new solutions for strategic choices.

Questioning one's individual perspective and the outcome of the perception and thinking process through self-critical self-awareness and self-reflection, therefore, lies at the core of dynamic capabilities. From the psychodynamic perspective, integrating a third position through an ‘objective observer’, who relays his perceptions, represents a solution to overcome individual blindness, one-sidedness, or emotional distraction. Being able to listen to third-party observations and perceptions enables the requested self-awareness and self-reflection over time. Psychotherapists, psychoanalysts and psychotherapeutically trained coaches can provide this third position in a training phase or as supervision, because they are especially trained not to confuse their own emotional reactions with the emotional reactions of the manager as client. This competency is key because negative emotions and defensive reactions are not easy to uncover and might initially provoke a denying and rejecting reaction of the manager before the new perspective can be accepted and integrated. Over time, the manager detects his/her individual pattern in emotional reactions to strategic decisions in times of high uncertainty.

Hence, for strategic decision makers, it not only makes sense but should be mandatory to be able to integrate the influence of emotions and the connected aspects into the strategic process through self-awareness and self-reflection, in order to keep from being unconsciously influenced by them and to make better strategic decisions. Without this reflection-and-integration process, there is no possibility of actively managing through times of uncertainty.

The second step – influences of fear and anxiety on the team level of the decision-making processThe generic dynamic capability in this second phase of strategy making is summarised with ‘seizing opportunities’. It represents the crucial moment of choosing a single strategy or a set of strategies to shape the future of the organisation. Because strategic decision-making processes in large and globally operating enterprises are no longer managed by single managers, but instead by a top management team and/or management board, this team needs to find a format or framework for strategic choice and necessary team dialogue for strategic discussion and decisions about future strategic directions and their implications. A team or a group being confronted with a difficult choice meets the emotions of fear and anxiety on an individual level as already described, but in addition, specific group mechanisms will add to the emotional complexity of the situation.

Uncertainty and anxiety within the top management teamOn the top team level, uncertainty has a dual role; not only has the top management to deal with uncertainty of the future as well as every other member of the organisation, but each top team member must deal with his/her individual feelings of uncertainty regarding the judgement and possible rejection of other group members when communicating his/her insights about the future. This holds especially true at the top of the organisation where the fear of losing face and reputation is especially high. The individual and group identities are hugely threatened when sharing perceptions, assumptions, and conclusions about the future of the organisation. On an individual level, this results in an emotional imbalance. Feelings of anxiety or fear can arise and result in the outlined individual emotional defence.

On a team level, the feeling of the group as an entity and as belonging together is also under threat. Since the human being as a social being demands from early childhood on to belong to a group, the threat of being expelled from a group creates an existential anxiety on the level of the individual. On the group level the belonging is created by group mechanisms on a sociological level as well as on a psychodynamic and sociodynamic levels. Whereas the sociological perspective looks at group dynamics regarding interactions, structures, roles, socialisation and physical space (territory), the psychological perspective focuses on emotional exchanges, identification, creation of a centre, in-group-out-group mechanisms and emotional space (Battegay, 1973). The group itself and its self-sustaining mechanism create a specific system of defences; as social defence mechanisms they happen between the team's members and its leaders.

Paradoxical choices also induce anxiety on the level of the management team. Whereas learning paradoxes evolve around individual processes of sense-making and development, paradoxes surrounding belonging turn around the tension between self and others and are concerned with individuality, group boundaries, and globalisation. Striving for self-expression and collective affiliation lays at the heart of this paradox, whereas blurring hierarchical boundaries and distinctions enforces it (Lewis, 2000). Although disrupting group decisions are needed in an increasingly digitised world, they foster fear and anxiety and are experienced as emotionally and cognitively threatening. By unconsciously applying individual and social defence mechanisms, managers are trying to avoid and manage away these unpleasant feelings. Lewis (2000) describes that projective and splitting mechanisms are likely to happen. Complemented by regression and projective identification, these are the basic psychodynamic mechanisms behind the depicted social defences here.

Groupthink and social defencesBest known in the context of management even by managers is the phenomenon of groupthink, although it only provides a cursory glimpse into the diversity of social defence mechanisms and comes into play under very specific circumstances. Janis (1972) analysed a number of specific political decision-making situation in the United States (Pearl Harbor, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Watergate affair). The responsible committees made bad or at least unrealistic decisions because every member of the group was subject to a supposed group opinion and held back her/his own opinion so as not to upset the ostensible harmony amongst the members. Factors that support development of groupthink are: (a) cohesion: the members of the group know each other well and value their opinions and therefore want to retain their harmonious state; (b) isolation: touchy subjects that cannot be discussed with others outside of the group – because of reasons of confidentiality – are debated; (c) high stress level: the significance and the complexity of a decision that must be quickly made place the group members under high pressure; (d) strong leadership: the highest-ranking decision maker has a clear, explicit opinion that he/she articulates in a dominant fashion. A specific set of behaviours is the result of groupthink: (a) self-censorship: group members do not articulate what they are thinking because they are afraid that they will open themselves up to criticism, make fools of themselves, or waste time; (b) peer pressure: those who deviate in their thinking believe that the group is requesting them to subscribe to the majority view; (c) illusion of invulnerability: collective feeling of overestimation of the group's own resources; (d) false reduction: influencing factors outside of the group are too easily simplified and stereotyped. In sum, it results in the group not looking at enough alternatives, which leads to decisions made that are far removed from reality.

Groupthink as well as other social defence mechanisms point, on the individual as well as on the organisational level, to the concept of social or organisational identity. And similar to individuals, organisations defend their already-existing identity, which in turn leads to a reduced willingness to learn and grow (Brown & Starkey, 2000). Social defences and complexes are psychic mechanisms on work group level, which help the individual and the group deal with anxiety, provoked by this necessary change into an unforeseeable future. These mostly unconscious mechanisms can either support or prohibit the fulfilment of the work group task. These social defences can have a double effect; while they help the individual and the group function as a work group, to deal with the negative feelings resulting from uncertainty, if they take over they may hinder work on the primary task (Hirschhorn, 1988). This may impede exploration of primary risks – when the task is to choose a task (Hirschhorn, 1999) – leading to a principal contradiction, and thus to an unresolved strategic dilemma (Sullivan & Langdon, 2008).

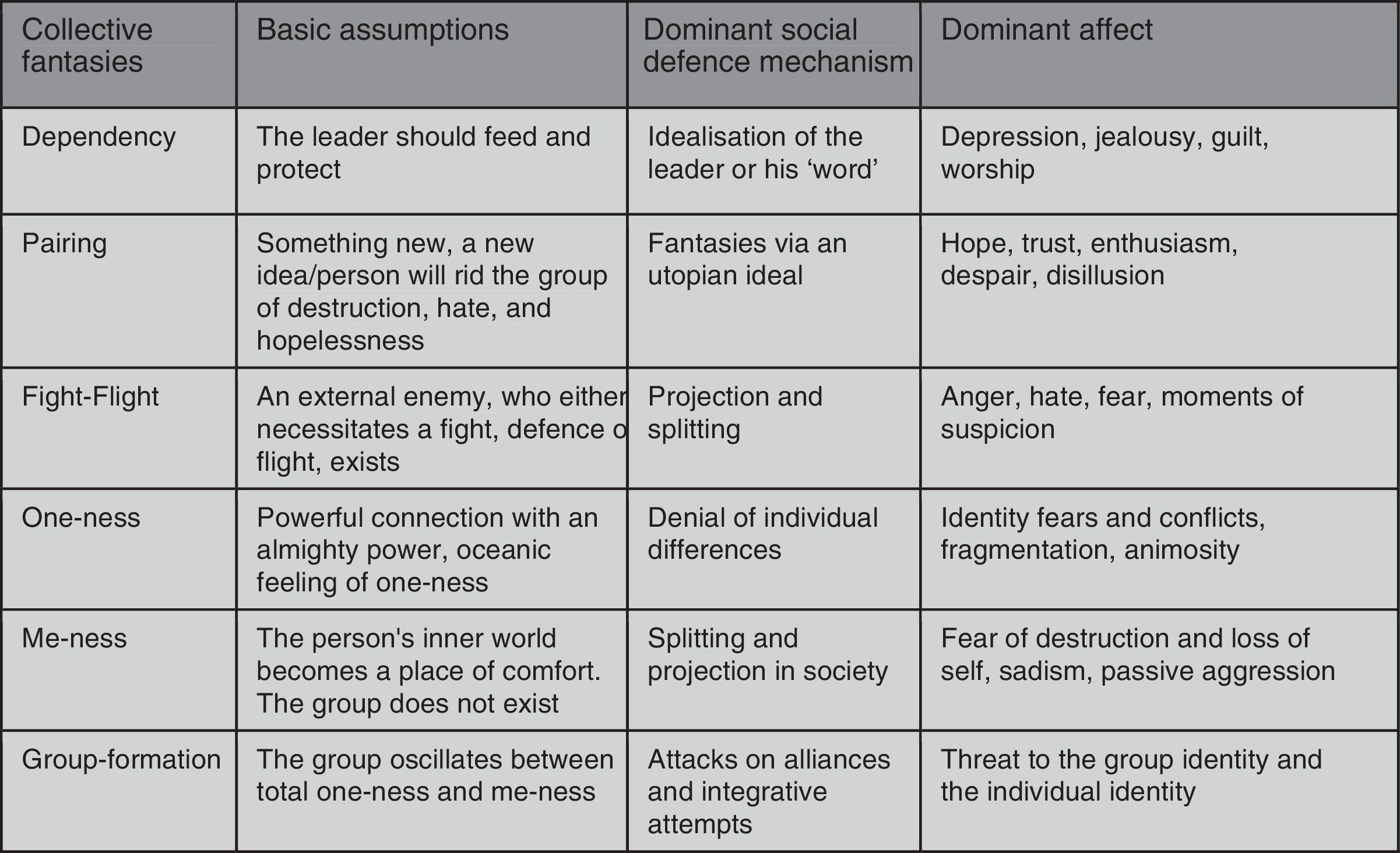

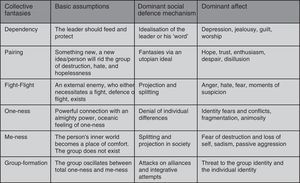

Social defence are well researched in form of “‘basic assumptions”’ (Bion, 1961). The basic assumption patterns are a specific mixture of affects and fantasies, so that symbolic realities and specific priorities for the perceptions and actions as well as for patterns of action arise (Bion, 1961; Kinzel, 2002). Six different basic assumption modes are discussed for work groups. They differ from their unconscious collective fantasies, the unspoken and unconscious basic assumption of the group for that fantasy which represents a kind of hope or solution for the group, the way the social defence works and the feelings of the work group, which the group members do not want to feel (unconsciously). They are depicted in Fig. 5.

A decision-making committee can oscillate between several basic assumptions and the work group mode (which means working on the primary task) so that it is not easily recognisable which mode is currently predominant (Kinzel, 2002). If the unconscious inner fantasy gains the upper hand and is then mistaken for reality, the external reality cannot be perceived in the correct way. Strategic decisions that are determined in this mode can be detrimental to a company in the long term, or the company can fail due to internal resistance that is not in line with the external reality (Fig. 6).

Stereotyping and rational heuristics as defenceEmotional imbalances on top team level lead to a number of major psychological challenges in the process of seizing a new strategic opportunity. First, new opportunities must be evaluated and selected. Second, fixations with existing strategies must be unlocked (Hodgkinson & Healey, 2011) and third, already-existing decision heuristics on a corporate level must be overcome (Bingham & Eisenhardt, 2011). Fourth, social stereotypes must be surmounted.

Shared rational heuristics develop over time when a company enters into new strategic situations, and slowly the managers become experts in this new strategy arena. To come to a shared good decision, it is important to detect company-specific heuristics and discuss their applicability. These heuristics are, as well as individual heuristics, based on experience and develop through application and learning (Bingham & Eisenhardt, 2011). They are rules the management establishes for itself during the development of a new strategy theme, to take the most important influencing factors into consideration during complex situations, to learn from experience, to communicate the experiences in a compact, easy-to-remember format. Thereby, a type of rulebook that is specific to the culture of the company for a certain type of strategic decisions is created. Of course, these self-imposed rules must (and this poses a problem) always be validated and modified, because they only work in a specific environment similar to that of when they were developed. So at any time, it must be checked if a specific heuristic suits a specific decision-making situation or if a new, shared thinking process has to be run through.

Stereotypes do have a similar effect on decision-making processes as heuristics; they shorten the time to come to a conclusion or decision since they create a shortcut for judgement. Stereotypes also have a specific task in human groups and society: they support individuals in improving their self-esteem through their identification as members of a particular group and, to the extent that their group is viewed more favourably than other groups; their self-esteem will be further enhanced (Tajfel, 1978). Most of the stereotypes function on an unconscious level. The effectiveness of these implicit stereotypes and prejudices can be verified by using the Implicit Association Test (Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998), which opens the eye to stereotypes one thinks one does not have. There are implicit stereotypes not only pertaining to race and gender, but they can be found in all areas of individual and corporate life (markets, nations, languages) and therefore play a nonobjective, influencing role in decision-making. Detecting influencing stereotypes in evaluating and selecting opportunities is a key task of the top team, and the capacity to allow for this process of uncovering probably mostly unwanted insights is a dynamic psychological work group capability.

Strategic discourse using a reflective space and paradoxial thinkingHealey, Vuori, and Hodgkinson (2015) argue that team performance depends on team coordination, which itself is influenced by different social cognitions, stemming either from the reflective or the reflexive system. The reflective and reflexive systems not only work on the individual level but are also understood to be influential on a team level. The reflective system of a team produces shared mental models about task and team, whereas the reflexive system uses implicit attitudes, subconscious goals, heuristics, and implicit stereotypes. Similarity of the mental models and representations of the x-system eases intra-team coordination whereas dissimilarity hinders it. Problematic for team coordination and thus therefore team performance is discordance between the reflective and the reflexive system representations. Intra-psychic conflicts add another layer to this matrix, which means that time pressure, cognitive (over)load and less team interaction make system x-representations of the individual gain more importance in their effect on individualistic behaviour and the pursuit of implicit individual goals.

When considering that the task of a top management team in this second step of developing a strategy is to pursue a strategic discourse with the goal of achieving a shared decision at the end, this also implies that shared cognitions or shared mental models need to be achieved as well as shared representations of the future organisation and its context on the reflexive or implicit level. The latter might be understood as a shared map of the future of the organisation and its context (strategy map). This leads to specific demands for the creation of a strategic discourse, not only acknowledging but also making use of the different representations on the reflective and the reflexive level, to stimulate a debate on the future of the organisation.

The strategic discourse has to develop over: (1) the individually different perceptions of strategically relevant facts; (2) their individual and group interpretation, and; (3) the underlying assumptions [see also the theory of social construction of reality developed by Berger and Luckmann (1966)], which then led to; (4) shared conclusions about how the actual reality and future developments are seen and evaluated, and ideally at the end, a; (5) shared conviction leading to; (6) a strategic choice and a shared strategy map resulting from this process.

The key competencies in leading this strategic discourse are what Healey et al. (2015) call ‘cross-understanding’ (understanding another person's mental models) on the c-system but also on the x-system level. From a psychodynamic perspective this requires three basic human features: (1) the basic capacity for introspection and self-reflection; (2) the willingness to communicate the insights from introspection and self-reflection, and; (3) the capacity for empathy as basal capacity for cross-understanding on implicit and explicit levels of thinking and feeling. Subsequently, they are needed to reflect in a shared thinking process on real arguments and their difference to assumptions and conclusions about the future of the corporation.

Whereas Hodgkinson and Healey (2011) restrict their focus on emotional constraints of choice on an individual level, it is shown here that it is promising when looking at the seizing capability to focus on emotional team dynamics during choice processes. When new strategic alternatives such as new technologies or entering new markets, can be positively associated with strong supporting emotions, emotional and cognitive commitment can be built. To establish a positive commitment on both levels a specific emotional set-up for the top team is needed, where group members can dare to share new and different views of rising opportunities. Psychologically speaking, a safe container (Bion, 1962) is needed, where every team member can allow himself to share his emotions, interpretations, and assumptions regarding the future and the respective interpretations.

Because paradoxes are an important aspect of strategic choice situations – on the level of the team as paradoxes of belonging as well as the basic strategic paradox regarding stability versus change – dealing with paradoxes has to become part of the reflective space. The strategic discourse can be a way of paradoxical thinking by addressing conflicts and critically examining assumptions on opposites (Schad et al., 2016). The tension of the opposites, which is often difficult to be held on an individual level can be moved out of the individual mindset to become debatable between the team members. Differentiating and integrating as well as transcending are practices that can be effectuated on the team level even better then on the level of the individual.

On top team level the most important dynamic capabilities of the group are first to be able to dynamically process ideas, fantasies, perceptions of opportunities; secondly to think jointly paradoxically; and thirdly to come to a shared decision on where to invest and commit resources as a corporation. Processing and deciding have to result in positive emotional and cognitive commitment and happen during a strategic discourse or in a shared thinking space. Creating this psychologically safe space for thinking is a foundational element of dynamic capabilities. This could result in a special ‘thinking space for the future’, which can be created to ensure that the core of dynamic capabilities, adaptability and agility, will come into being. The quality of thinking in this space is based on the aforementioned self-awareness and self-reflection of each individual member and must also allow for a joint strategic reflexivity (x-system) and reflectivity (c-system), resulting at least partially in a process of shared paradoxical thinking moving away from trade-off perceptions towards a paradox mindset (Schad et al., 2016). To come to a joint strategic decision, this reflective space allows for deep reflection and reflexion in order to come to a joint discourse in which assumptions, associated feelings, and their respective backgrounds, the underlying rational heuristics and implicit stereotypes, and also their conclusions, are uncovered. They are turned into topics that can be discussed so that their influence on the strategic thought process steps out of the unconscious and can be consciously understood and integrated into the decision.

The third step – the implementation of the decision-making process and its factors of influencesImplementing a strategy is a demanding process and involves reconfiguring the base of both tangible and intangible assets. Implementation and reconfiguring assets are also coined as ‘change’. There is already an extended literature on change management and its success factors (e.g., Burke, Lake, & Paine, 2008; Pettigrew & Whipp, 1991; Tichy, 1983). Their fundamentals include theories regarding organisational behaviour, organisational development, action research, group dynamics, systems, complexity, and other fields. Often missing in this change and strategy implementation literature is the role of the unconscious and the respective social defence mechanism based on psychodynamics and explicitly analysing the effects of fear, anxiety, and uncertainty on systems.

The best way to describe people's behaviour within an organisation on an organisational level is the concept of organisational culture. It is one of the most researched fields in organisational behaviour and has over the years become a field of his own (Schein, 1987). In Schein's framework, organisational culture as a pattern of shared basic assumptions learned through experiences represents the organisational way to perceive, think, and feel. Therefore, it influences all decision-making processes and the implementation of the decisions taken. Because this phenomenon is so well worked through, it is more relevant here to focus on the emotional level behind the basic underlying assumptions, which only come up under stress and uncertainty. A helpful concept in this regard is the corporate complex.

Corporate complexes are the organisational response to psychological complexes on the individual level. The notion of complexes was introduced by Jung (1924/1995). He used the term to describe a form of more or less unconscious psychic contents held together by an identical emotion and a common core of meaning. As an unconscious focal point of psychic processes, it is charged with a high degree of negative or positive emotional energy and is linked with an archetypal image. Having a complex means that the emotional and cognitive tension between the two conflicting poles of a complex is – similar to a paradox – not managed by the respective individual. Unconscious anxiety and fear hinder the active coping with the conflicting demands of the situation so that the individual either reacts one-sidedly neurotic or one of the already-described individual defence mechanisms is acted out, depending on the emotional level of maturity.

The notion of corporate cultural complexes (Kimbles & Singer, 2004) is connected with the basic idea of the collective unconscious, also introduced by Jung (1927/1995). They come into being on an organisational level and belong to corporate culture. Because they function on the level of the whole organisation, they are based on common historical experiences and are repeated and anchored in the unconscious of the group. These complexes can be stirred up in the corporate cultural unconscious at any time and can engross the group's collective psyche, whereby the corporate unconscious captures the perceptions, behavioural patterns, and feelings so that the irrational effects are created in terms of their own logic.

Corporate cultural complexes often are the result of traumatising experiences (investment or product failures, mergers, take-over, fraud) or discrimination, and develop through feelings of suppression and inferiority in connection with an oppressed group. Cultural complexes are experienced at group level, but they are internalised on an individual level. They provoke the same psychic defence mechanism on group or corporate level as on the individual level, therefore all described individual defences account for the group level. Both the cultural and the individual complexes are bipolar. One aspect is acted out within the group, while the other aspect is projected onto another foreign group. Similar to an individual complex, the cultural complex conveys a simplistic safety in an otherwise ambivalent, conflictual uncertainty (Kimbles & Singer, 2004; Nagel, 2014). Corporate cultural complexes can thus destroy or hinder, if not acknowledged and integrated, the implementation of a chosen strategy and impede, or even make asset reconfiguration impossible.