The solitary fibrous tumour (SFT) was first described as a pleural neoplasm in 1931 by Klemperer and Rabin.1 Since then, approximately 800 cases of SFT have been reported, with 85–90% of these reports relating to SFT of the visceral pleura.2

A case of a rare subepithelial lesion in the gastro-oesophageal junction is described below:

50-year-old man, smoker, who went to the A&E for haematemesis, preceded by melaena. Haemodynamically stable. Physical examination normal. Blood tests normal.

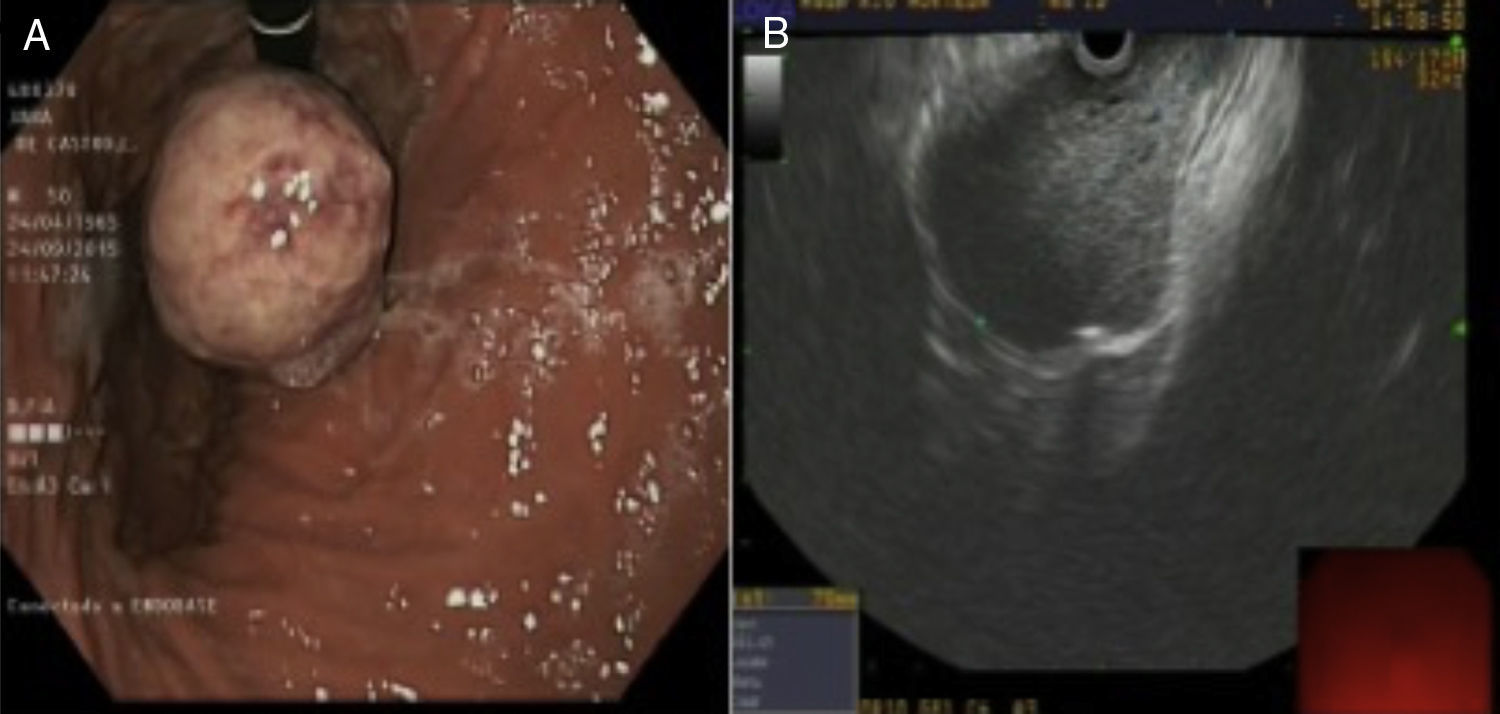

The gastroscopy revealed a non-ulcerated, pendulous lesion measuring 5–6cm, with a probable underlying introduction in the cardia. Suggestive of subepithelial lesion (Fig. 1A).

The study was completed with an endoscopy: a subepithelial lesion was observed in the distal oesophagus, below the muscular layer itself, with well-defined margins and which passed through the cardia into the gastric fundus (Fig. 1B). The findings are suggestive of a potentially malignant mesenchymal tumour. A four-step, 22-g, transgastric fine-needle aspiration (FNA) puncture was performed, recovering little material, the histological study of which showed mesenchymal spindle-cell neoplastic proliferation. The immunohistochemistry test showed CD34 (+), actin (+) and c-KIT (−). The low representation of mesenchymal proliferation described is highly suggestive of gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST), despite not expressing c-KIT.1

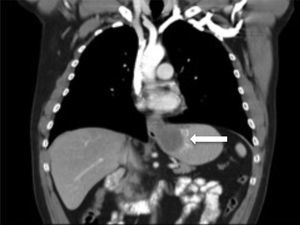

The thoracoabdominal CT scan conducted revealed a submucosal tumour measuring 7.5cm in the distal oesophagus, extending into the cardia, with an endoluminal growth extending into the gastric body, and with no adenopathies (Fig. 2).

Due to a suspected GIST diagnosis, as well as the need for histological confirmation, it was decided that a full surgical resection via upper-pole gastrectomy with distal oesophagectomy be performed, followed by mechanical gastro-oesophageal termino-lateral anastomosis.

The anatomopathological study revealed a mesenchymal neoplastic lesion measuring 7cm, with epithelioid neoplastic spindle cells, combined with plasma cells, and a significant level of eosinophils. No vascular endothelial proliferation, necrosis or mitotic figures were observed. Immunohistochemistry was positive for vimentin, CD34 and CD99, with c-KIT (CD117) and Bcl-2 completely negative. Ki-67 proliferation index of 3%. All of these findings are consistent with benign SFT of the gastro-oesophageal junction, with tumour-free resection margins.

The patient was discharged 11 days after surgery, with no complications. He is currently being monitored.

SFT is a rare neoplasia below the mesothelial surfaces, mainly pleural and peritoneal, although cases have been reported in all anatomical areas.2 It occurs in adults aged between 20 and 70 years and is more common in women.3 It does not usually produce symptoms until it reaches a considerable size. In intra-abdominal cases, it presents as a palpable mass, accompanied by pain and weight loss. Refractory hypoglycaemia or Doege-Potter (paraneoplastic) syndrome induced by the introduction of the type II insulin-like growth factor, present in 5% of pleural SFTs, seems to be a rare symptom in intra-abdominal SFTs.2

The CT scan is the radiological diagnostic method of choice. For gastro-oesophageal SFT, however, endoscopy provides more information than the CT scan, because it enables a histological study to be carried out through the FNA puncture4; this is characterised by areas of spindle-cell proliferation within the collagen-rich stroma.5 SFT would be considered malignant if it presents with mitotic activity markers that are greater than 4 figures per 10 high-power fields, or if there is necrosis, increased cellularity, increased tumour size, nuclear pleomorphism or stromal infiltration beyond the pseudocapsule or vascular invasion.

The immunohistochemistry profile includes a combination of positive markers for vimentin, CD34, Bcl-2 and CD99 and immunonegative markers for actin, desmin, S100 protein and other epithelial markers. These markers allow us to distinguish SFTs from other stromal tumours,5 such as GISTs and leiomyoma, which are very common in the stomach and oesophagus, respectively, and with which we perform a differential diagnosis. GISTs express the CD117 antigen, whereas leiomyoma and other spindle-cell tumours in the gastrointestinal tract are typically CD117 negative. Likewise, approximately 90% of the GISTs express the KIT gene which is negative for SFT.5

Recently, a molecular pathognomonic marker for SFTs was identified that involves the genetic fusion of NAB2-STAT6 by reverse transcription in chromosome 12q13. This fusion causes the NAB2 to be converted from a transcriptional inhibitor to a potent EGR1 transcriptional activator, which would give rise to neoplastic progression. These findings are very important for establishing new lines of study on future treatments.3,6

The final treatment involves the complete removal of the tumour, which is the only way to fully confirm the diagnosis. Despite being indolent, with survival rates of 73–100%, SFTs should always be treated as potentially recurrent and metastatic tumours. Recurrence rates of 1.4–12% have been observed in the case of benign tumours and of up to 55% in the case of malignant tumours.2,7

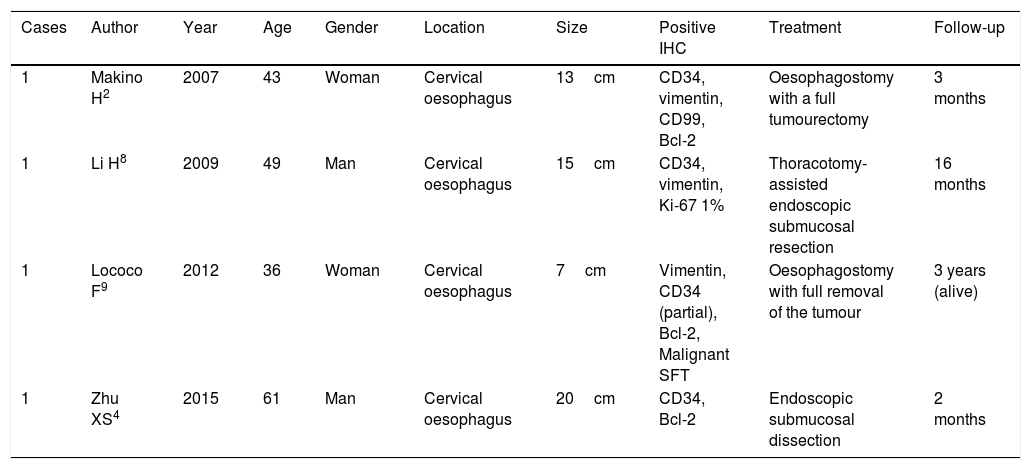

To conclude, SFT is a rare, low-incident neoplasm that should be considered as a differential diagnosis for other subepithelial lesions of the oesophagus and the rest of the gastrointestinal tract. According to the revised bibliography, until 2015 there were only four cases of oesophageal SFT (Table 1), with this being the first report of SFT in the gastro-oesophageal junction.2,4,8,9

Cases published on solitary fibrous oesophageal tumours in the last 10 years.

| Cases | Author | Year | Age | Gender | Location | Size | Positive IHC | Treatment | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Makino H2 | 2007 | 43 | Woman | Cervical oesophagus | 13cm | CD34, vimentin, CD99, Bcl-2 | Oesophagostomy with a full tumourectomy | 3 months |

| 1 | Li H8 | 2009 | 49 | Man | Cervical oesophagus | 15cm | CD34, vimentin, Ki-67 1% | Thoracotomy-assisted endoscopic submucosal resection | 16 months |

| 1 | Lococo F9 | 2012 | 36 | Woman | Cervical oesophagus | 7cm | Vimentin, CD34 (partial), Bcl-2, Malignant SFT | Oesophagostomy with full removal of the tumour | 3 years (alive) |

| 1 | Zhu XS4 | 2015 | 61 | Man | Cervical oesophagus | 20cm | CD34, Bcl-2 | Endoscopic submucosal dissection | 2 months |

Please cite this article as: Plúa Muñiz KT, Otero Russel R, Velasco López R, Rodríguez López M, García-Abril Alonso JM. Tumor fibroso solitario de la unión gastroesofágica. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:33–35.