To establish recommendations for the management of psychological problems affecting patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

MethodsA meeting of a group of IBD experts made up of doctors, psychologists, nurses and patient representatives was held. The following were presented: (1) Results of a previous focal group, (2) results of doctor and patient surveys, (3) results of a systematic review of tools for detecting anxiety and depression. A guided discussion was then held about the most important psychological and emotional problems associated with IBD, appropriate referral criteria and situations to be avoided. The validated instrument most applicable to clinical practice was selected. A recommendations document and a Delphi survey were designed. The survey was sent to the group and to a scientific committee of the GETECCU group in order to establish the level of agreement with these recommendations.

ResultsFifteen recommendations were established linked to 3 key processes: (1) What steps should be taken to identify psychological problems at an IBD appointment; (2) what are the criteria for referring patients to a mental health specialist; (3) how to approach psychological problems.

ConclusionsResources should be made available to healthcare professionals so that they can treat these problems during consultations, identify the disorders which could affect the clinical course of the disease and determine their impact on the patient's life in order that these can be treated and followed up by the most suitable professional. These recommendations could serve as a basis for redesigning IBD services or processes and as justification for the training of healthcare personnel.

Establecer recomendaciones para el manejo de los aspectos psicológicos de los pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII).

MétodosSe llevó a cabo una reunión con un grupo de expertos en EII formado por médicos, psicólogos, enfermeras y representantes de pacientes. Se presentaron resultados de: 1) un grupo focal previo, 2) encuestas a médicos y pacientes y 3) una revisión sistemática sobre instrumentos de cribado de ansiedad y depresión. Se realizó una discusión guiada sobre los aspectos psicológicos y emocionales más importantes en EII, los criterios de derivación apropiados y situaciones a evitar. Se seleccionó el instrumento validado más aplicable a la práctica clínica. Se diseñó un documento con recomendaciones, así como una encuesta Delphi. La encuesta fue enviada al grupo y a un comité científico seleccionado del grupo GETECCU, con el objetivo de establecer el grado de apoyo a las recomendaciones establecidas.

ResultadosSe establecieron 15 recomendaciones, pertenecientes a 3 procesos clave: 1) qué pasos dar para identificar problemas psicológicos en consulta de EII, 2) criterios de derivación a profesionales de la salud mental y 3) abordaje de los problemas psicológicos.

ConclusionesSe deben facilitar recursos a los profesionales sanitarios para que puedan tratar estos aspectos en consulta, identificar los trastornos que puedan afectar el curso de la enfermedad o su impacto en la vida del paciente, para ser tratados y seguidos por el profesional más adecuado. Estas recomendaciones pueden servir de base para el rediseño de los servicios o procesos de EII y como justificación para la formación del personal sanitario.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of chronic intestinal disorders that have an impact on patients’ quality of life. Individuals with IBD often have psychological disorders, which may or may not be associated with the disease, including anxiety or depression.1–3 The disease itself can also sometimes flare in response to psychological problems and stress has been described to have a significant impact on the number and intensity of IBD flare-ups.4–6 Patients with uncontrolled psychological disorders have been reported to use healthcare resources (unscheduled visits, phone consultations, emergency department visits) more frequently,7,8 show poor treatment adherence9 and have a poor quality of life,1,10,11 all of which indicates that psychological intervention may be beneficial to them.12

The biopsychosocial model, which is currently the recommended approach for patients with any disorder, recommends detecting and treating patients’ psychological problems and not focusing only on their physical problems.13,14 This is because it has been proven that controlling psychological symptoms, information and adaptation improve the doctor–patient relationship and the course of the underlying organic disease.9,15

An earlier study by the Spanish Working Group on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (GETECCU) showed the importance that both doctors and patients with IBD give to psychological problems. It also demonstrated the system's failure to manage such problems, with a discrepancy between doctor and patient perceptions of the impact of certain aspects, and a lack of training for healthcare professionals who manage the psychological problems of IBD patients.16

This group therefore decided to establish recommendations for the identification and management of psychological problems that can be used as guidelines by professionals who treat IBD patients. These recommendations are based on data from their own earlier studies and have been approved by healthcare professionals and patients.

MethodsA working group comprising 3 doctors, 2 psychologists, 1 nurse and 1 patient representative (selected based on their experience and interest in this issue) was established. They were presented with the following at a nominal group meeting: the results of a prior patient focus group, which have been described in detail in another publication,17 the results of questionnaires given to doctors from GETECCU and patients from the Association of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis Patients (ACCU) (designed by the working group at an earlier stage),16 and a systematic review of anxiety and depression screening instruments, with the most suitable anxiety and depression screening instrument for clinical practice being selected from all the validated instruments reviewed. Clinical practice guidelines for IBD that included certain recommendations for psychological problems were also reviewed. Based on the above, a guided discussion was conducted on the most important psychological problems and how to manage them.

Based on all the comments noted at the meeting, a matrix document was then drafted to facilitate online discussion. Using this document, a questionnaire was prepared comprising the points or recommendations made by the panel and using a modified Delphi technique. The questionnaire was sent to the panel and to members of a scientific committee selected from GETECCU members (all IBD consultants and potential users of these recommendations) in order to establish the level of consensus for the established recommendations. Members had to vote for each recommendation using a scale from 0 to 10. A blank space was also left after each recommendation for comments. Those recommendations that did not meet consensus (standard deviation greater than 2) were re-evaluated in a second round. Recommendations receiving less than 75% consensus were eliminated from the list of recommendations. Finally, the level of evidence for each recommendation based on supporting studies was appraised and graded using the Oxford Levels of Evidence, 2011.18

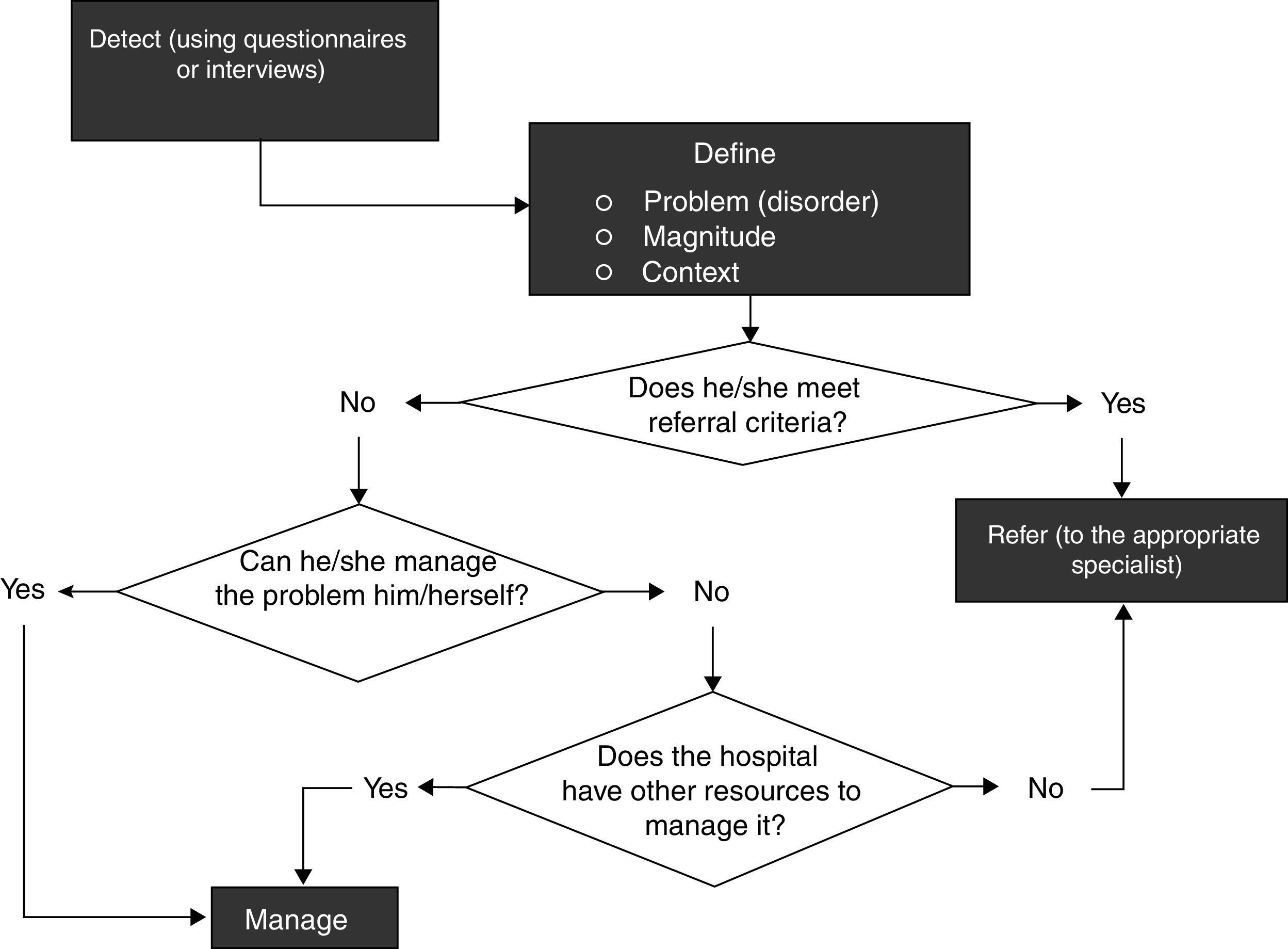

After the first meeting of the panel, it was determined that the document would have 3 parts, a recommendations part for its prevention and identification and for disease management, a part relating to referral criteria, and a part on actions or attitudes that should never be adopted. Finally, based on the discussion, it was possible to establish the complete process for managing these problems, involving (1) detect, (2) define and (3) manage, according to the algorithm in Fig. 1.

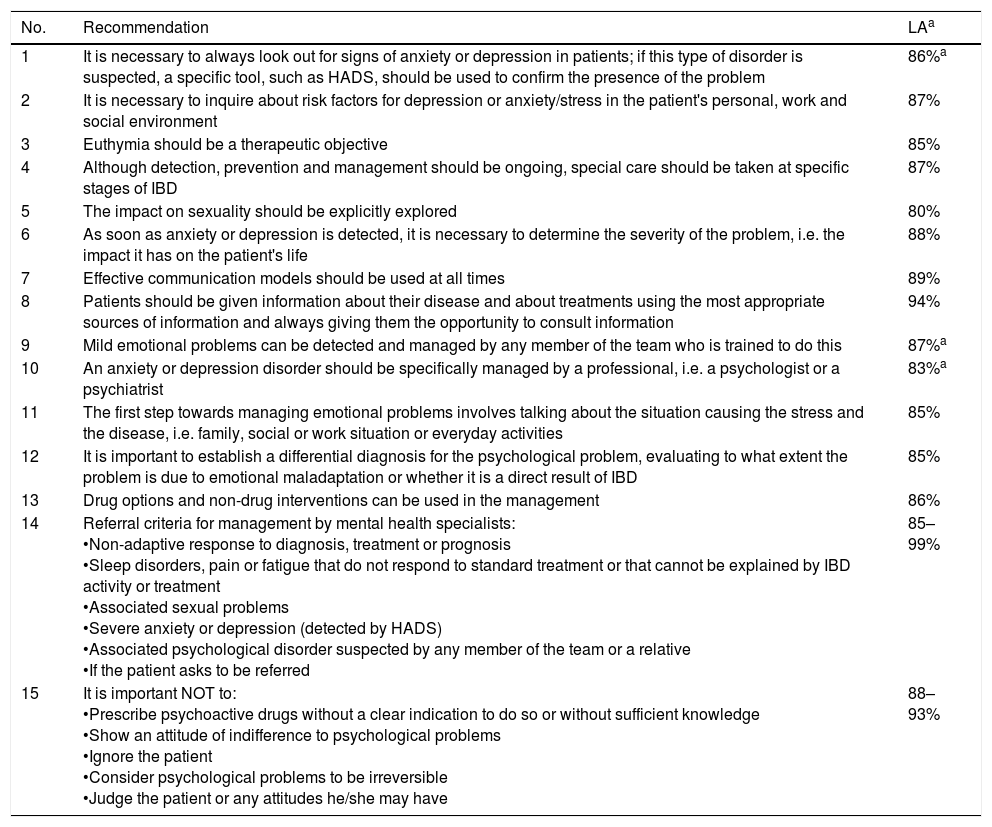

ResultsThe working group drafted 3 levels of recommendations: general management recommendations, referral criteria and actions or situations to be avoided. The recommendations established are outlined below with their level of agreement (LA), mean percentage of expert agreement, level of evidence (LE), strength of recommendation (SR) and a brief explanation (see Table 1 for a list of the recommendations).

General management recommendations, referral criteria and situations to be avoided.

| No. | Recommendation | LAa |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | It is necessary to always look out for signs of anxiety or depression in patients; if this type of disorder is suspected, a specific tool, such as HADS, should be used to confirm the presence of the problem | 86%a |

| 2 | It is necessary to inquire about risk factors for depression or anxiety/stress in the patient's personal, work and social environment | 87% |

| 3 | Euthymia should be a therapeutic objective | 85% |

| 4 | Although detection, prevention and management should be ongoing, special care should be taken at specific stages of IBD | 87% |

| 5 | The impact on sexuality should be explicitly explored | 80% |

| 6 | As soon as anxiety or depression is detected, it is necessary to determine the severity of the problem, i.e. the impact it has on the patient's life | 88% |

| 7 | Effective communication models should be used at all times | 89% |

| 8 | Patients should be given information about their disease and about treatments using the most appropriate sources of information and always giving them the opportunity to consult information | 94% |

| 9 | Mild emotional problems can be detected and managed by any member of the team who is trained to do this | 87%a |

| 10 | An anxiety or depression disorder should be specifically managed by a professional, i.e. a psychologist or a psychiatrist | 83%a |

| 11 | The first step towards managing emotional problems involves talking about the situation causing the stress and the disease, i.e. family, social or work situation or everyday activities | 85% |

| 12 | It is important to establish a differential diagnosis for the psychological problem, evaluating to what extent the problem is due to emotional maladaptation or whether it is a direct result of IBD | 85% |

| 13 | Drug options and non-drug interventions can be used in the management | 86% |

| 14 | Referral criteria for management by mental health specialists: •Non-adaptive response to diagnosis, treatment or prognosis •Sleep disorders, pain or fatigue that do not respond to standard treatment or that cannot be explained by IBD activity or treatment •Associated sexual problems •Severe anxiety or depression (detected by HADS) •Associated psychological disorder suspected by any member of the team or a relative •If the patient asks to be referred | 85–99% |

| 15 | It is important NOT to: •Prescribe psychoactive drugs without a clear indication to do so or without sufficient knowledge •Show an attitude of indifference to psychological problems •Ignore the patient •Consider psychological problems to be irreversible •Judge the patient or any attitudes he/she may have | 88–93% |

HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; LA: level of agreement.

1. It is necessary to always look out for signs of anxiety or depression in patients with IBD; if this type of disorder is suspected, a specific tool, such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), should be used to confirm the presence of the problem. (LA: 86%; LE: 1 a; SR: A)

This recommendation is based on a systematic review of observational studies with a high degree of homogeneity that confirms the high frequency of both disorders (20% anxiety and 15% depression) in patients with IBD.3 With regard to how to identify these disorders, and given that it is not feasible to perform a thorough psychological examination in the limited time available for medical consultations, we have systematically reviewed screening instruments that would have been tested on the clinical population if their use in consultations was feasible. Of all the instruments presented, the panel selected HADS,19 which has 14 questions, as the most useful and applicable questionnaire for medical consultations, which does not imply that other instruments cannot be used. It is important to remember that patients may not only have anxiety or depression, and it is a good idea to ask them about use of antidepressants or anxiolytics, prior diagnosis of any mental disease and substance abuse, including alcohol.

2. It is necessary to inquire about risk factors for depression or anxiety or stress in the patient's personal, work and social environment. (LA: 87%; LE: 3; SR: C)

If the patient expresses the cause of his/her anxiety or stress, this has been observed to actually reduce anxiety.20 Some factors that contribute to stress, which should be inquired about, include: (1) family (dependants, relationship issues, parents–children or health problems or other types of problem affecting a family member), (2) work (type of work and job, experience, work environment, risk of dismissal due to illness, sick leave, unemployment, upcoming retirement), (3) social (isolation, limited social network, insecurity, legal proceedings) and (4) personal (perfectionism, introversion, competitiveness, aggression or insecurity, low income, permanent care for others, menarche or menopause). It is also important to consider clinical aspects, including stage of IBD (flare-up/remission) and procedures (invasive tests, surgery) or progression.

3. Euthymia should be a therapeutic objective. (LA: 85%; LE: 2b; SR: D)

Euthymia is understood to be a normal mood for a given situation and could be considered the ideal mood state. Given that numerous studies demonstrate the effects of anxiety, depression and negative stress on disease prognosis,4–6 keeping these aspects under control should be another therapeutic objective in the follow-up of these patients.

4. Although the detection, prevention and follow-up of psychological disorders should be ongoing, special care should be taken at specific stages of IBD. (LA: 87%; LE: 3; SR: D)

An earlier questionnaire by the group showed the existence of times when there is a greater risk of stress, such as onset to diagnosis and assimilation of the disease, hospital admission or surgery, especially in the case of an ostomy, during flare-ups, when IBD is accompanied by fatigue and limited performance, and in the event of episodes of faecal incontinence in public.16

5. The impact on sexuality should be explicitly explored. (LA: 80%; LE: 3; SR: C)

Sexual problems are very common in IBD, and tend to be accompanied by high levels of stress.21,22 The patient should be encouraged to express his/her concerns or needs regardless of his/her age, thereby normalising the situation and giving suitable advice to improve sexuality.21,22 If severe problems in this area are detected, it is a good idea to refer the patient to experts (psychologists, gynaecologists or urologists, depending on the problem), either directly or through patient associations.

6. As soon as anxiety or depression is detected, it is necessary to determine the severity of the problem, i.e. the impact it has on the patient's life. (LA: 88%; LE: 5; SR: D)

If a patient has anxiety or depression, this may have completely different consequences based on the impact it has on the patient's life or disease. It is important to ask the patient which activities he/she has had to stop and how important this is to him/her as each patient has his/her own value scale. These specific aspects can then be used to monitor progression of the patient's psychological disorder on an individualised basis.

7. Effective communication models should be used at all times. (LA: 89%; LE: 4; SR: D)

It is possible to prevent the development of anxiety, depression or stress disorders by using effective communication.20 This specific type of communication involves: (1) adapting to the patient's knowledge, which can be learned by directly asking “what do you know about…?” using adapted language; (2) adapting to the patient's need for information, which can be learned by directly asking “what are you most interested in learning about…?”; (3) healthcare professional accessibility, in terms of organisational, economic, cultural and emotional barriers; (4) giving clear expectations and alternative therapies; and (5) allowing emotional venting,15,23,24 i.e. allowing the patient to express his/her emotions while actively listening.

8. Patients should be given information about their disease and about treatments using the most appropriate sources of information and always giving them the opportunity to compare information. (LA: 94%; LE: 4; SR: D)

Giving the patients information helps reduce their levels of anxiety.25 There is a lot of information about IBD, and this should be offered in a gradual, individualised manner, using all available resources.26 In addition to explanations given during medical consultations, available sources of information may include leaflets or documentation, websites or internet apps, educational talks, etc. Time should be allowed to answer any queries in a reasonable manner, either at the next visit (if not too far away), during an appointment with the nurse, or by email or over the phone. Providing contact information for a patient association may greatly simplify this task. Patients report feeling great relief after discovering there are additional sources of information – even if they do not use them – even if everything is explained to them in great detail at their medical appointment.16,17 Protocols should be established to outline what information should be provided, on who and how this should be done.

9. Mild emotional problems can be detected and managed by any member of the team treating patients with IBD who is trained to do this. (LA: 87%; LE: 5; SR: D)

Members of the team should be able to tackle purely reactive or endo-reactive disorders of the disease. As already discussed, it is important to identify individuals with a better capacity for effective information and empathy, and the patient should always be asked if he/she prefers to be assessed by a mental health professional (see referral strategies below).

If the patient or given circumstances require such an assessment, other options should be sought, such as psychologists or patient associations. It may be possible to delegate to specific psychological support services provided by patient associations, according to the situation and patient's preferences (see referral criteria).

10. An anxiety or depression disorder should be specifically managed by a professional, i.e. a psychologist or a psychiatrist. (LA: 83%; LE: 5; SR: D)

An endo-reactive disorder, such as getting nervous before an endoscopy, is one thing, but a long-term non-adaptive or disabling reaction is another thing entirely. In this case, there are mental health professionals who are better equipped to manage the patient than gastroenterologists (see referral criteria below).

11. The first step towards managing emotional problems involves talking about the situation causing the stress and the disease, i.e. family, social or work situation or everyday activities. (LA: 85%; LE: 3; SR: C)

Talking about the factors causing the stress is the first step towards effective management.20 Although mental health professionals should manage properly identified mental disorders, the panel wanted to highlight the need to talk about stress-causing factors in the context of previously diagnosed anxiety or depression, where the incidence will be even higher. Although a mental health professional can perform this examination, it is important that someone from the digestive diseases team make a note in the referral of other factors that may be causing stress from a clinical point of view.

12. It is important to establish a differential diagnosis for the psychological problem, evaluating to what extent the problem is due to emotional maladaptation or whether it is a direct result of IBD. (LA: 85%; LE: 5; SR: D)

Anxiety or depression in patients may be a consequence of the disease or may have been present before, contributing to the genesis of symptoms.1,5,27,28 This evaluation should also be performed by the healthcare professional to whom the patient has been referred, but always alongside the information provided by the IBD unit.

13. Drug options and non-drug interventions can be used to manage depression and anxiety. (LA: 86%; LE: 1b; SR: A)

The mental health professional, or properly trained members of the team, may use non-drug or drug options, if required, such as mindfulness, meditation or relaxation techniques, yoga and physical activity for therapeutic purposes (aerobic physical activity at least 3h a week, therapeutic exercises).20,27,29 Offering advice on effective approaches for stressful events has also been shown to be useful.30 The patient should be allowed to express his/her emotions and any type of manifestation should be validated, even if he/she cries, shouts or gets angry, without trying to contain these emotions, but rather expressing that these are normal and common but fleeting.

Referral criteria for management by mental health specialistsThe following criteria are established for referral to either a psychologist or psychiatrist, depending on the specific situation:

- 1.

Non-adaptive response to diagnosis, treatment or prognosis. (LA: 86%)

- 2.

Sleep disorders, pain or fatigue that do not respond to standard treatment or that cannot be explained by IBD activity or treatment. (LA: 87%)

- 3.

Associated sexual problems. (LA: 85%)

- 4.

Severe anxiety or depression (detected by HADS). (LA: 99%)

- 5.

Associated psychological disorders recognised or suspected by any member of the team or a relative. (LA: 84%)

- 6.

If the patient asks to be referred. (LA: 90%)

Panellists recognise that referral to other professionals is not always easy, and they have therefore suggested some strategies to make referral easier, such as arguing the importance of the biopsychosocial (bidirectional) model, ensuring feedback from the psychologist or psychiatrist to whom the patient is referred, establishing action protocols, including a psychologist on the team or providing a specific logbook for patients with IBD, using emotional interview techniques or obtaining advice from other individuals with IBD (expert-patient associations or programmes).

Actions or attitudes to be avoidedThe panel determined that it is important never to adopt the following actions or attitudes:

- 1.

Prescribing psychoactive drugs without a clear indication to do so or without sufficient knowledge. (LA: 91%)

- 2.

Showing an attitude of indifference to psychological problems. (LA: 90%)

- 3.

Ignoring the patient. (LA: 93%)

- 4.

Considering psychological problems to be irreversible. (LA: 90%)

- 5.

Judging the patient or any attitudes he/she may have. (LA: 88%)

The recommendations presented in this article deal with the management of psychological problems in IBD. More specifically, this consensus document offers recommendations about: (a) the steps to be taken to identify psychological problems at IBD appointments; (b) criteria for referral to mental health professionals; and (c) management of these problems by the team treating IBD. The recommendations particularly have an impact on the identification and follow-up of the most common psychological disorders affecting IBD management. The working group established that these disorders are depression and anxiety or stress. It is important to explain to both healthcare professionals and IBD patients, however, that the onset of transient emotional disorders at the time of specific events, such as diagnosis, certain tests or procedures, or when starting new treatments, form part of a normal adaptation process and disappear naturally after a certain time. It is also important to highlight that, although social aspects are also vitally important to disease progression and may affect psychological problems, these recommendations are limited only to psychological problems, regardless of their determinants.

One of the most original contributions of this document is probably the importance of achieving a therapeutic objective, euthymia, which may be interpreted as “psychological remission”.31 Very different therapeutic objectives are sometimes suggested for patients with IBD; however, there is limited information available on strategies for achieving “psychological remission”. The working group has evaluated a fundamental problem for IBD patients that, in general, has not previously been considered important by doctors or other healthcare staff.29,32 It has demonstrated the importance of properly managing psychological problems associated with IBD, using, for example, effective communication methods, which are not always used at medical appointments.23 In order to be able to prevent, detect, define and control these problems, the professional must adopt a biopsychosocial approach and explore more unusual areas, such as psychological issues or sexuality, in an attempt to understand the patient as a whole and not just the disease. The professional should also give the patient a much more active role in his/her disease. In addition to giving peace-of-mind and controlling psychological symptoms, this new doctor–patient relationship will enhance self-management of the disease, with adequate information provided during appointments and an improved climate of trust.14,23,28 Although patients prefer to receive information from their doctor,21,28 the doctor may not have enough time or may have difficulty building a trusting relationship with the patient; also doctors do not always feel comfortable dealing with personal issues because they have not been trained properly in this area.33 The group discussed the opportunity of assigning the informant role to the most empathetic member of the team for the patient's benefit; however, the final stance was to train all members of the team in effective communication techniques. We must all improve our ability to inform patients and their families.

During the consensus process, some of the panel's initial recommendations were modified to accommodate the majority opinion of those consulted. For example, the first recommendation was drafted as follows during round 1: “We recommend using a strategy, or specific tools such as HADS, to identify anxiety or depression in patients with IBD”. However, the votes and opinions of the panellists revealed that, as a result of this recommendation, they understood the need to use a single method for collecting information. We therefore redrafted the recommendation and clarified in the explanatory text that we do not recommend any single method for inquiring about problems, but that HADS may be used as it was the instrument given the best score by the panel and the instrument that best suits the occasion. Recommendation 9 also had to be redrafted. It initially recommended that “Emotional problems directly associated with IBD can be detected and initially managed by any member of the team if he/she has been trained”. Comments showed problems interpreting the word “training”, which we attempted to correct by stressing that we were referring to mild problems. The psychologists proposed including the term “psychoeducation” in the recommendation, but, given that this is not a concept regularly used by non-psychological staff, we rejected this suggestion. Nevertheless, psychoeducation refers to emotional support and problem solving, which can be done with active listening and information. The last recommendation to cause disagreement was recommendation 10, which initially stated “An anxiety or depression disorder should be specifically managed by a professional, i.e. a psychologist or a psychiatrist”. It was not the panel's intention to establish a fixed recommendation regarding which mental health professional should treat patients with IBD, especially considering that each patient has problems of varying severity and cause and available resources, or better-quality resources, may vary from one scenario to another. Nevertheless, the panel did want to highlight the importance of not medicating patients with non-severe problems, if at all possible. Finally, we decided to delete some referral criteria regarding therapeutic failure and service overuse from the relevant section of the final document, as the necessary level of agreement was not achieved.

There was also some debate among experts on whether a suggestion should be made as to which specific member of the team should be responsible for providing information to patients. Providing adequate information normally requires more time than usual, and, therefore, estimated consultation times should take into account the informing act in order to be effective. It is also important that the person providing information on the disease and its complications is empathetic. The team must decide which of all the members is most appropriate for regularly providing information to patients. It may also sometimes be appropriate for each member of the team to provide part of the information and to reinforce information provided by other professionals. Finally, the panel decided not to include any suggestions in the recommendations regarding making one specific person responsible for providing the information as the aim is to improve and enhance the communication abilities of all members of the team.

One of the limitations of the document is the poor level of scientific evidence for many of the recommendations. It must be understood that it is very difficult to put forward studies that provide evidence for recommendations, as these imply healthcare service and research structure strategies with little economic support or support from research structures in general. Therefore, studies have partly been based on earlier qualitative studies conducted by the same group, EnMente. We have also tried to overcome this lack of evidence with the experience of both gastroenterologists interested in the matter and psychologists as patient representatives.

In addition, these recommendations are of no value if they are not actually applied in clinical practice. The difficulty of adapting some of the proposals to the busy hospital departments and logistical appointment, professional accessibility or multidisciplinary care framework is something that has already been highlighted in the literature34 and that was widely discussed by the panel. The panel preferred to allow the professionals at each centre to decide how to manage such issues, including working groups, online professionals35 or the support of patient associations. Nevertheless, minor changes in the doctor–patient relationship will have the greatest impact.8 We believe it is especially important to improve training on psychological problems for professionals who treat patients with IBD since it has been shown that better communication, including integration of psychological problems into the doctor–patient relationship,26 has a positive effect on adherence and prognosis.9 It is also a skill that can be taught and that does not necessarily imply increased consultation time, as many tend to believe.8,24,36

This document is based on a review of clinical practice guidelines for IBD regarding psychological problems, a focus group involving Spanish patients with IBD, a patient and doctor questionnaire and a systematic review of the usefulness of anxiety and depression screening instruments in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. The working group has multiple perspectives, and patients have played a leading role. We therefore believe that these perspectives are particularly valid, despite the poor level of scientific evidence for many of them. This document includes practical recommendations for the management of psychosocial problems in IBD that may be useful for redesigning IBD services or processes and as justification for training healthcare staff.

FundingMSD provided economic and logistics support for the meetings and studies without playing a role in any scientific aspects.

Authors’ contributionMBA, IMJ, AP, JG, MC, MGM and YM were involved in designing and conducting the study that has resulted in this article.

GA, MMBW, XC, FC, MCH, LFS, RFI, DG, MI, NM, MM, OM, MR, OR, LS, PV, YZ, MM, PN and JPG were involved in reaching consensus using the Delphi questionnaire.

All authors were involved in drafting the text and approving the final version.

Conflicts of interestMBA has been a consultant, speaker or has received research grants from MSD, AbbVie, Hospira, Takeda, Khern, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Chiesi, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Tillotts Pharma.

IM-J has been a consultant, speaker or has received research grants from MSD, AbbVie, Hospira, Takeda, Janssen, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Chiesi, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca and Tillotts Pharma.

JG has been a consultant, speaker or has received research grants from MSD, AbbVie, Ferring, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Gebro Pharma, AstraZeneca, General Electric, Kern and Tillotts Pharma.

MMBW has been a consultant, speaker or has received research grants from MSD, AbbVie, Takeda, Ferring, and Shire Pharmaceuticals.

FC has been a consultant, speaker or has received research grants from AbbVie, MSD, Shire, Ferring, Zambon and Gebro.

MCh has provided scientific consultancy, research support and/or training activities to MSD, AbbVie, Hospira, Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen, Ferring, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma and Tillotts Pharma.

RF has provided scientific consultancy, research support and/or training activities to Tillotts, AbbVie, Falk and Shire.

PVV has been a speaker for MSD, AbbVie, Ferring, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Kern Pharma, Faes Farma and Takeda.

YZ has been a consultant, speaker or has received research grants from MSD, AbbVie, Hospira, Takeda, Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Tillotts Pharma.

M. Mínguez has been a consultant, speaker or has received research grants from MSD, AbbVie, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Almirall, Takeda and Allergan.

PNM has been a consultant, speaker or has received research grants from MSD, AbbVie, Hospira, Takeda, Janssen, Khern, Ferring, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Chiesi, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Tillotts Pharma.

JPG has provided scientific consultancy, research support and/or training activities to MSD, AbbVie, Hospira, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Biogen, Takeda, Janssen, Roche, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi, Casen Fleet, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Vifor Pharma.

All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Barreiro-de Acosta M, Marín-Jiménez I, Panadero A, Guardiola J, Cañas M, Gobbo Montoya M, et al. Recomendaciones del Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) y de la Confederación de Asociaciones de Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (ACCU) para el manejo de los aspectos psicológicos en la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:118–127.