A solitary fibrous tumour (SFT) is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm of fibroblastic origin, representing less than 2% of all soft tissue tumours.1,2 Originally it was described in the pleura, and was initially considered a serous tumour1; however, in recent years cases have been documented arising in virtually any anatomical location and organ3; currently it is estimated that extrapleural origin is more common.1,4 We present a case of abdominal SFT, dependent on the minor gastric curvature, without any associated symptoms, which was found casually during an abdominal computed tomography (CT) for another reason.

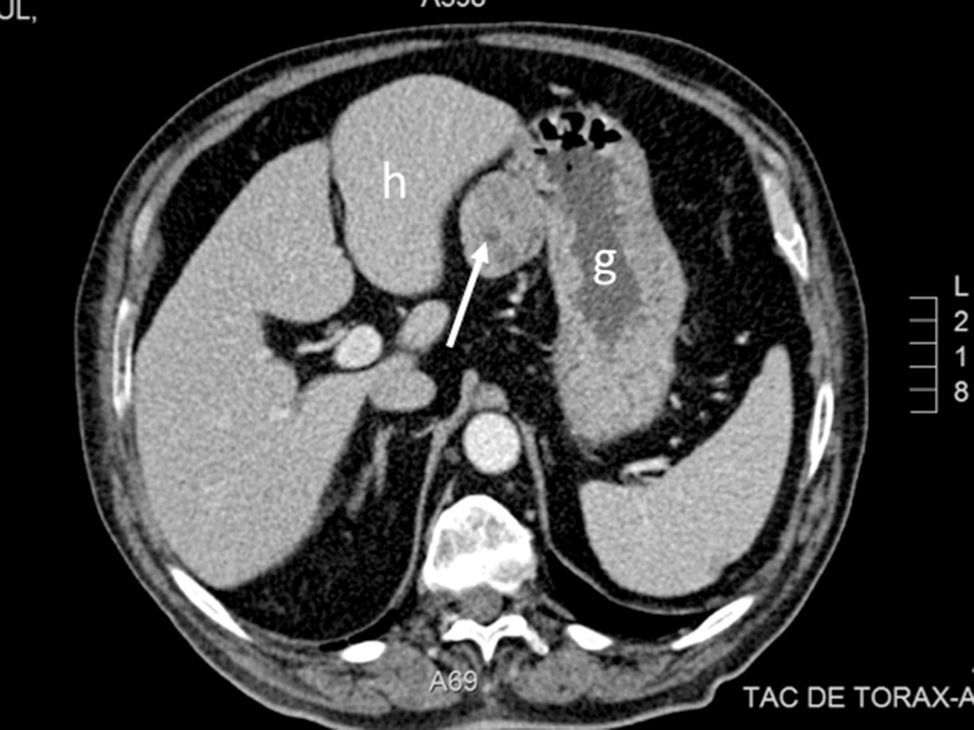

The case is a 69-year-old male with a history of type II diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischaemic cardiomyopathy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and sleep apnoea syndrome, undergoing treatment with metformin, glimepiride, sitagliptin, acetylsalicylic acid, torasemide, eplerenone, bisoprolol, enalapril and valsartan. He reported symptoms which had lasted several months of diarrhoea, asthenia and weight loss. The physical examination showed no significant abnormalities. A gastroscopy and colonoscopy were performed, with no relevant findings. An abdominal CT scan was carried out, in which a solid, homogeneous mass was observed, 4.3cm in its largest diameter, located on the gastrohepatic ligament and related to the minor gastric curvature (Fig. 1). With a suspicion of resectable gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST), surgery was scheduled. During the surgery a tumour was observed in the minor gastric curvature, protruding towards the anterior fold of the lesser omentum. A laparoscopic resection was conducted, including spindle-shaped excision of the full thickness of the gastric wall without notable incidents. The histological study showed a 6×5×4.5cm tumour, well delimited, made up of a homogeneous proliferation of fusiform cells with a whorled pattern, discrete cellular atypia, occasional mitotic figures, as well as a fibrous stroma and abundant vascular structures with perivascular hyalinisation, consistent with SFT. The resection margins were free of tumour infiltration. The mitotic index was less than 2 mitotic figures/10 high power fields and the proliferative index was low (Ki-67 of 1%). The immunohistochemical study was positive for CD34, vimentin and Bcl-2, and negative for CD99, calretinin, c-Kit, DOG-1, D2-40, S-100, desmin and actin. The post-operative period elapsed without complications.

In the current classification of soft tissue tumours, the term ‘SFT’ encompasses haemangiopericytomas, as well as SFTs themselves, previously considered independent conditions.5,6 It is a rare neoplasm, of fibroblastic origin, that affects adults aged 20–70. Histologically, it is characterised by hypo- and hypercellular areas, with fusiform cells surrounded by areas of fibrosis and collagenous stroma and a vascular pattern with branched vessels. The immunohistochemical study tends to be positive for CD34 and, less commonly, for CD99 and Bcl-2.3,5 It has recently been established that SFT is characterised by the fusion of NAB2 and STAT6 genes of chromosome 12, leading to the overexpression of STAT6, its activation and migration into the cell's nucleus. This change probably constitutes the initial pathogenic mechanism that explains the tumour growth. Also, high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity has been observed in the nuclear positivity of STAT6 in the immunohistochemical study.3,6

Although SFT was initially considered a tumour of pleural origin, later reports established that it could take hold in any organ, including the peritoneum, retroperitoneum, liver, lungs, stomach, bladder and prostate, and it can affect head and neck structures such as the parotid, thyroid, orbit and mouth, subcutaneous cellular tissue and, more rarely, skin.3 Currently it is considered that 60–70% of cases have an extrapleural origin.4,7 In the most comprehensive series, abdominal location is notable for its frequency, in 30% of cases4,7; however, a gastric or gastrohepatic ligament origin is exceptional.8,9

SFT is generally a localised and benign tumour, although in 15–20% of cases it exhibits aggressive behaviour leading to local invasion or metastatic disease.1 The factors that have been associated with this evolution are age, tumour size and the presence of a high mitotic index, cellular atypia, necrosis, haemorrhages or an infiltrative tumour border.1,4,5 Recently a risk stratification model has been developed based on age, tumour size and mitotic index.4

The treatment of choice for SFT is surgical removal. The efficacy of radiotherapy and conventional chemotherapy is very limited. The abundant vascular component of these tumours suggests that anti-angiogenic agents could be of use.1 Also, understanding the basis of tumourigenesis (NAB2-STAT6 fusion) opens the door to the possibility of new treatments directed at these molecular targets in cases of non-resectable or advanced disease.3

Please cite this article as: Calvo Zorrilla I, Gutiérrez Macías A, Loureiro González C, López Martínez M. Tumor fibroso solitario gástrico. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:527–529.