Protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) is characterised by an excessive loss of serum proteins through the gastrointestinal tract, primarily causing hypoproteinaemia with hypoalbuminaemia and oedema. When a patient has hypoalbuminaemia with oedema, other causes of decreased serum protein levels, such as malnutrition, kidney disease with proteinuria or liver impairment with alteration in protein synthesis, should first be ruled out.1

There are different causes of PLE, including metabolic, intestinal, inflammatory and infectious disorders, and alterations in lymphatic drainage, such as occurs in intestinal lymphangiectasia.1

We report the case of a 57-year-old woman who had two episodes of idiopathic acute pancreatitis in less than a year. In that year, the patient developed palpebral and lower extremity oedema with persistent hypoalbuminaemia, with serum albumin levels <2g/dl (normal 3.30–5.20), a decrease in the concentration of γ-globulins and short half-life proteins, without diarrhoea. In the investigations performed at that time, faecal elastase and faecal fat tests were normal. Alpha-1-antitrypsin clearance was 797ml/24h (normal 0.00–12.50) and the bacterial overgrowth test, stool cultures and stool analysis for parasites were negative. Nephrotic syndrome was also ruled out as a cause of hypoalbuminaemia.

The patient subsequently had a further episode of acute pancreatitis with splenic vein thrombosis for which she was started on anticoagulation; treatment was also started with corticosteroids, as autoimmune pancreatitis was suspected despite normal IgG4. She showed no improvement but instead had another exacerbation of pancreatitis. A hypercoagulability study was performed with factor V Leiden, proteins C and S, antithrombin III, homocysteinaemia and prothrombin 20210, which were all within normal limits. A month later, positron emission tomography scan showed an increase in uptake in the tail of the pancreas, suspected to be of malignant origin. In the end, a distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy was performed via laparotomy; pathology was compatible with chronic pancreatitis (inflammation and fibrosis associated with areas of necrosis).

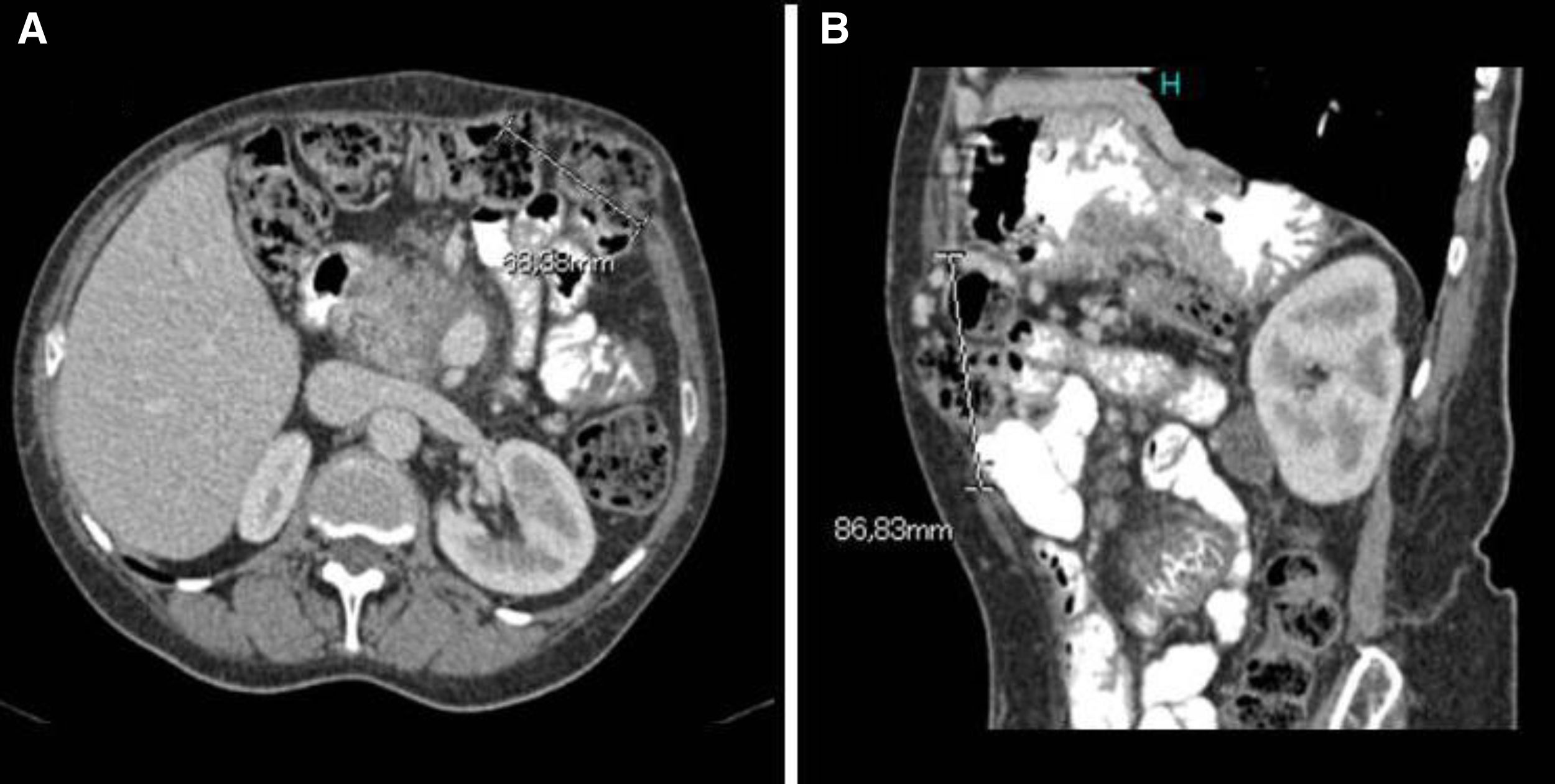

As the hypoalbuminaemia persisted, the patient was started on parenteral nutrition, leading to a slight improvement in blood test parameters (serum albumin 2.6g/dl) and improvement clinically. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy identified duodenal and jejunal lymphangiectasia. Causes of secondary lymphangiectasia were ruled out, except for chronic pancreatitis, which the patient already had. Colonoscopy was also performed, showing mucosa with normal appearance. One year after starting the parenteral nutrition, the patient developed pancreatic pain resistant to first- and second-step analgesics, with no diarrhoea or weight loss. MRI and endoscopic ultrasound showed severe chronic calcifying pancreatitis in the head of pancreas and a cyst measuring 35mm in the wall of the duodenum. She was started on octreotide and FNA confirmed the inflammatory nature of the contents of the cyst. In view of the poor pain control, a coeliac plexus block was performed, which provided pain control for a year. After that same period of time, an abdominal CT detected a subcostal incisional hernia related to the surgical wound (Fig. 1). The hernia was repaired laparoscopically, after which the patient experienced an improvement in her pain. At the same time, her serum albumin levels improved and she was able to stop the parenteral nutrition. Six months after the intervention, serum albumin was 4.21g/dl and alpha-1-antitrypsin clearance was 37.96ml/24h.

Resolution of PLE following laparoscopic hernia repair is not a common event. In our case, intestinal lymphangiectasia was caused by chronic pancreatitis and aggravated by the subcostal hernia. This event, secondary to distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy, caused lymphatic congestion, which led to leakage of lymph with a large amount of proteins into the intestinal lumen. However, following the hernia repair and the consequent decrease in abdominal pressure and lymphatic congestion, the condition resolved both clinically and analytically. The fact that the diagnosis of PLE was previous to the development of the hernia suggests that this was a factor added to the chronic pancreatitis.

Intestinal lymphangiectasia can be primary or secondary; the first affects children and is characterised by ectasia of the intestinal lymph vessels in the mucosa or submucosa, with disorders in the lymphatic system in other parts of the body.2 In secondary intestinal lymphangiectasia, the lymph vessels become dilated either due to obstruction in the lymphatic system or high lymphatic pressure resulting from high venous pressure. The obstruction may be associated with heart disease, which is the most common cause, Budd-Chiari syndrome, liver cirrhosis, enterolymphatic fistulas, cardiac surgery such as the Fontan procedure, inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis, lymphoma or chronic pancreatitis.

The most characteristic symptoms are peripheral oedema, ascites, pleural or pericardial effusion and diarrhoea.3 For the diagnosis of intestinal lymphangiectasia it is important to first confirm the excessive loss of proteins in the gastrointestinal tract, where a useful marker is the clearance of alpha-1-antitrypsin. A clearance >28ml/24h without diarrhoea or >57ml/24h with diarrhoea is abnormal.1 Once the loss of proteins is confirmed, the definitive diagnosis of lymphangiectasia requires endoscopic assessment with duodenum and/or jejunum biopsies.

There are very few cases in the literature discussing any link between abdominal hernia or eventration and PLE.4–6 In 2005, Tainaka et al. described the case of a girl with PLE caused by a paraduodenal hernia whose serum proteins and albumin returned to normal after surgery.4 In our case, it was a subcostal hernia after open abdominal surgery. Hernia is a common complication of abdominal surgery, with an incidence that varies from 2% to 20%.7,8 The incidence in pancreatic debridement is even higher, reaching 42%.9 The signs and symptoms vary from none at all to abdominal pain with complications such as incarceration. As far as treatment is concerned, in most cases, it involves repair of the wall with placement of non-absorbable prosthetic mesh.10

Please cite this article as: Aguilera Castro L, Téllez Villajos L, López San Román A, Botella Carretero JI, García García de Paredes A, Albillos Martínez A. Enteropatía pierde-proteínas resuelta tras la reparación de una eventración abdominal. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:313–315.