This paper aims to hint at a theory of family business naming. Besides, it puts forward two kinds of practical proposals. The former intends to integrate the patronymic name as an intangible resource for corporate brand management, in addition to family branding and familiness. The latter proposals aim at including the patronymic company name in Spanish as a variable in research methods on family business identification.

Nuestro trabajo realiza apuntes para una teoría del nombre de la empresa familiar. Además, este trabajo formula 2 tipos de proposiciones prácticas. Las primeras, para integrar el nombre patronímico como un recurso intangible para la gestión de la marca corporativa, al servicio también del family branding y familiness. Las segundas proposiciones, para incluir el nombre de empresa patronímico como variable en la metodología, en investigaciones sobre la identificación de la empresa familiar.

Many studies on naming have been carried out from linguistic, morphological or semantic perspectives (Chang & Huang, 2001; González del Río, Ampuero, Jordá, & Magal, 2011; Klink, 2000, 2001). The field of study that deals with proper names is called Anthroponomy or Onomastics. There are also psychological (Lowrey, Shrum, & Dubitsky, 2003) and marketing (Aaker, 1991, 1996, 2004) approaches to naming that pay attention to the brand name of products and services.

The business name can have a direct or indirect effect on businesses’ general and commercial success. Notwithstanding the import of naming for business excellence at all levels, there is little research on business naming in scientific texts. Nowadays, business naming is one of the least researched intangible aspects. With a focus on family business, our work on brand naming brings closer two fields that have hardly been studied in conjunction: corporate naming and family business. It interrelates the contributions on family branding, which have been recurrently analysed from perspectives far from strategic management and corporate governance. This issue is very often found in family business studies, as family branding is commonly regarded as an unimportant, almost insignificant subject.

When reviewing previous studies of corporate branding, we endorse Muzellec's (2006) distinction between two types of references. The most numerous are those studies that stress the commercial function of the firm name: The predominant conception of naming spotlights its nexus with the external public. The focus is on the impact of business relations and of sale of a brand name. This is the line followed by King (1991), Aaker (1991, 2004), Kotler (1992). According to Brown and Dacin (1997) and Dacin and Brown (2002), a corporate name is a means for conveying corporate associations to the clients.

Robertson (1989) addresses the economic dimension and notes that naming is an investment with economic return: the more appropriate, the less advertising expenses for the company. The least numerous are those studies that suggest a corporate and strategic function of the firm name in its global nexus with the organisation or with the promotion of internal values, along with its engagement with the stakeholders or further aspects of corporate identity. This line of research is pursued by Hatch and Schultz (1997, 2003), Ind (1998, 2003), Balmer and Gray (2003), Kollmann and Suckow (2007), Olivares (2011) and Olivares, Benlloch, and Pinillos (2015). Dowling (1996) and Balmer (2001) also point out that if inadequately managed, naming has a negative impact on the whole firm.

Other contributions in this line are those by Balmer and Greyser (2002, 2003) and De Chernatony (2002). Naming also communicates corporate associations with the clients, according to Brown and Dacin (1997) and Dacin and Brown (2002). Swystun (2008) says that brand names are valuable economic assets that their owners must create and protect. Besides, Swystun (2008) considers that naming also embraces corporate identity, the actual essence of the firm, its values and its behaviour.

We accept that the name is part of the distinctive elements of a brand (Aaker, 1991, 1996, 2004; Costa, 2004, 2013; King, 1991). Likewise, we should assume that the name, at least in the same proportion, acts on the overall income account attributable to the corporate brand and that of products and services.

An (in)adequate choice of the firm name – especially of the brand name, in a context of management of intangibles – can affect the companies’ income statement (Olivares, 2011; Olivares et al., 2015). A strategically and morphologically suitable business name has a positive influence on the stakeholders and has a measurable and quantifiable impact on the whole organisation. A suitable firm name is instrumental in initiating, maintaining and enhancing commercial and institutional relations and connections. The name, for instance, does not go unnoticed among its internal public or its current or prospective stakeholders. An unsuitable firm name – beyond linguistic, semantic or cultural reasons – can negatively influence commercial and corporate outputs of the family business and, as a result, its present and future value. On the other hand, a suitable name – strategically aligned with the general interests of the company – can positively affect confidence among investors and the major economic indicators of the company.

In addition to an exhaustive and critical review of the literature, the interest of this work lies in the combination of diverse outlooks, thereby producing a multiplying effect that unveils connections and possibilities, theoretical or methodological, strategic or operational.

Review of literatureMuzellec (2006) studies the specificity of the corporate name. He alludes to certain links between the corporate name and such issues as business economy, market value or financial health of the firm. Muzellec (2006) states that the name is the only valuable asset, and that for firms and corporate brands the name is an element through which each addressee perceives the company.

As we see it, the business name can serve to convey a particular way of being and of doing business, of liaising with employees, of reinforcing a satisfying experience for consumers, or of inspiring confidence and reliability to the financial community.

In their study of 130 US companies, Kashmiri and Mahajan (2010) conclude that family businesses that use the patronymic or family name as their brand name possess higher levels of social responsibility, listen to their customers better and do better than those businesses that do not use the founders’ names.

Following Kashmiri and Mahajan (2010), Pinillos (2014) studies corporate naming in family businesses in Spain. His work includes a quantitative analysis of the naming criteria applied to family business, depending on a number of corporate variables such as size, time in business, turnover, regional origin, economic sector, ownership or the generation that runs the family business.

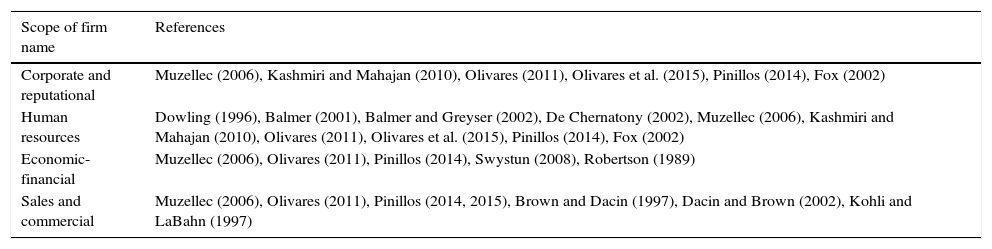

In short, as observed in the literature, the influence and scope of the corporate name is regarded from diverse perspectives (see Table 1).

The scope of the business name in the literature.

| Scope of firm name | References |

|---|---|

| Corporate and reputational | Muzellec (2006), Kashmiri and Mahajan (2010), Olivares (2011), Olivares et al. (2015), Pinillos (2014), Fox (2002) |

| Human resources | Dowling (1996), Balmer (2001), Balmer and Greyser (2002), De Chernatony (2002), Muzellec (2006), Kashmiri and Mahajan (2010), Olivares (2011), Olivares et al. (2015), Pinillos (2014), Fox (2002) |

| Economic-financial | Muzellec (2006), Olivares (2011), Pinillos (2014), Swystun (2008), Robertson (1989) |

| Sales and commercial | Muzellec (2006), Olivares (2011), Pinillos (2014, 2015), Brown and Dacin (1997), Dacin and Brown (2002), Kohli and LaBahn (1997) |

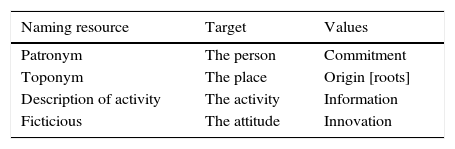

Researchers suggest very similar typologies of product and business naming. Most of them (Fontvila, 2013; Fox, 2002; Kohli & LaBahn, 1997; Kohli & Suri, 2000; Mollerup, 1998; Room, 1987; Swystun, 2008) consider at least: patronymics or personal names, toponyms (place names or demonyms), descriptive (often of the activity or sector), ficticious (or creative, evocative, suggestive, etc.), with some variant (abstract, symbolic, etc.) and acronyms or initials (contracted or abbreviated forms).

In this paper we refer to the patronymic as a naming solution that includes – totally or partially, directly or indirectly – acronyms, the proper name of the founders or of a relevant personality for them, or some family names of the family clan (upwards or downwards) for naming the company. This is done for the corporate name, for the trade name of the corporate brand or the brand name of products and services. The term matronymic is used when the abovementioned refers to a woman. In general terms, we use the patronymics, the founders’ name and family name interchangeably. In this article, we do not follow a strict definition of the patronymic – the surname that children take from their parents – that comes from the father's proper name (see Fig. 1).

The toponym is the naming resource that employs a place name or demonym for naming the firm, often the place of origin or geographical area of natural influence of the company. The description of the activity is the naming solution that makes use of the company's main activity. The ficticious or creative resource builds the company's brand name in an original, arbitrary, invented, suggestive and evocative way. And all the abovementioned are often integrated in the brand name explicitly/directly or implicitly/indirectly (by means of acronyms and initials) (see Table 2).

Kashmiri and Mahajan (2010) point out that family businesses often adopt the founders’ proper name or the family name as their corporate name. Besides, Muzellec (2006), Olivares (2011), Olivares et al. (2015) and Pinillos (2014) state that this is the most frequent naming resource for family businesses. According to these studies, the most frequent naming resource for corporate naming in family businesses is the patronymic, followed by the description of the activity, the toponym and ficticious or creative names, which are scarcely used. Acronyms and initials are used on a relatively regular basis, although there is a growing trend to use fantasy or creative names for the new firms so that the naming physiognomy might change in decades.

Pinillos (2014) points out that corporate naming often resorts to hybrid patronymics combined with other resources or principles: they are often merged with toponyms (founders’ proper name and name of geographic area) or with the activity (founder's proper name and economic sector or category). Naming often involves inverting the order of syllables or vowels (playing or creating with the founders’ proper name or surname). This author suggests that, to a lesser extent, the corporate name is built from open, creative or fantasy criteria. Family businesses set up most recently – more within the new digital economy – are increasingly turning to these less traditional criteria to create their brand names. One of the most common errors when classifying names according to the creative resources employed is to regard them as exclusive categories. In fact, a firm name might have been created from various criteria: for instance, the combination of the patronymic, the toponym and description of activity.

Name and family business: advantages of the patronymic and of the family name as a familiness resourceHabberson and Williams (1999) allude to familiness to refer to a series of specific resources and expertise of the family business that result from the interaction between family and firm. Olivares (2011, 2012a, 2012b) talks about the “family business” brand as one of these resources. The administration of the names, and specifically of the patronymics, where family and firm use a common element – the founders’ proper name of the family name – would be thus linked to familiness in order to obtain differentiation and competitive advantages, in this case via corporate intangibles.

Patronymic and reputation of family businessReputation is an issue of common concern for family business scholars (Craig, Dibrell, & Davis, 2008; Deephouse & Jaskiewicz, 2013; Fombrun & Shanley, 1990; Zellweger, Eddleston, & Kellermanns, 2010).

Other scholars coincide that family firms “are required” to be good corporate citizens, as there is much more at stake than in other companies because of their commitment, due to the reciprocal and explicit association between the founders or their family and the firm (Dyer & Whetten, 2006; Godfrey, 2005; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2005; Miller, Le Breton-Miller, & Scholnick, 2008; Niehm, Swinney, & Miller, 2008; Whetten & Mackey, 2002). The naming coincidence between family and business is one of the motives that would have an effect on social responsibility.

Kashmiri and Mahajan (2010) conduct an investigation on the link between the patronymic of the company and such intangibles as reputation and corporate social responsibility. For Dyer and Whetten (2006), Olivares (2011) and Olivares et al. (2015), the reputation of the family often rests on the central role of the family business name (when derived from the founders’ name or family name).

Sometimes the patronymic is hidden under acronyms and initials and, therefore, not explicit in the firm name. Albeit the naming resource is ultimately the same, its impact on stakeholders would be different. We believe that there are family business names which other scholars label as acronyms or initials that must be regarded as patronymics. Sometimes encrypted in an acronym or initial, the strategic potential of the patronymic is also encrypted or latent, and would be only activated if such connection between the acronym and the founders’ name were made explicit.

As regards reputation, the use of the patronymic as a denominative resource for companies and their products and/or services draws on a bi-directional and direct flux:

- 1.

First, from the founders and their values towards the whole company, and from the latter to its products and/or services.

- 2.

Second, from the company and its products and services towards the family new generations.

On using the founders’ and family name to call a company, a tribute is paid to the entrepreneurs and founders, the shareholders, or their families, by means of the family name, which centralises fame, reputation, credibility and trust.

Relationship of the patronymic with other intangible assets of the family businessResearch conducted by the University of Texas professors Kashmiri and Mahajan (2010) on a sample group of 130 US family businesses, from 2002 to 2006, shows the following relevant results:

- a.

Family businesses using the family name pay more attention to the consumers’ opinions than those that do not use the founders’ or family name.

- b.

Family businesses strategically emphasise the creation of added value through advertising, as a result of managing the reputation of the company. Those firms that do not use the family name place more emphasis on R+D.

- c.

Family businesses with family names exert greater social responsibility, as they possess minor social weaknesses and fewer constraints.

- d.

Finally, this piece of research seems to demonstrate that family businesses using the patronymic obtain a higher return on investment than those without the patronymic.

- e.

There is a current debate on whether family firms should keep their traditional name or if they had better replace it with a business name that conveyed a “more professional” corporate image.

- f.

This study corroborates that the name of a family business conveys a crucial form of trustworthiness, and guarantees fame and reputation.

In family businesses it is customary to show certain admiration and veneration – sometimes excessive – for the firm name. For business families and family businesses, the corporate name is a great legacy (Dyer & Whetten, 2006), a heritage, an asset, almost worthy of veneration; something that must be respected and kept, and that is often regarded as a part of the history of the firm and as a non-negotiable piece of the family business project. The family business name often moves the whole family and the whole company to action. It can also be a guarantee and a seal of confidence for all the stakeholders.

Corporate naming is scarcely referred to in non-empirical texts, and they are often mere extrapolations of findings in the field of product naming. However, we view this approach as unsuitable to seriously address corporate naming and to obtain the efficient corporate performance from the prevailing scenario in family businesses. Naming is often regarded as and isolated and single element, when in fact, we argue, it is a plural and articulate resource that combines with other intangible assets.

We foreground the strategic dimension of corporate naming, especially when it involves the use of the name of the original founder, a person related to the founders or the family name (in this article, we refer to this as patronymic). The patronymic corporate name can be managed as an intangible resource for family businesses, at the service of the family brand and brand management – via engagement and alignment with the stakeholders – and as a resource of familiness. The business name is an important pillar in the creation and management of corporate branding, given its numerous interrelations and its yet under-researched effects in the stakeholders. Within the latter, we take heed of the internal stakeholders and the business family.

The nexus between family and company, by means of the patronymic, if managed and integrated as an element of familiness, may enhance the identification, distinctiveness and recognition at all levels. These are precisely the functions assigned to the brand. Be it the founders’ – patronymic – or the family's, the name is the first communicative vehicle of the family business status; it builds trust if the integral behaviour of family and business is excellent. Thus, an unswerving link and association between name and reputation is established.

Our work is also relevant because it paves the way for a theory of corporate naming which has hither to received little attention, with some exceptions. We make a theoretical and methodological contribution to the potential use of the “double corporate name”. We determine that firms often have two names although in practical terms they operate with only one (this is subject to change depending on the country). A comprehensive and simultaneous overview of social or corporate term or business name of the brand or company reveals a myriad of possibilities for management and research that we express as propositions. This time we focus on firm names that refer to one person; the founder or a person of their choice, using their own name; or a family clan, using the family name (see Fig. 2).

Our rationale aims to empower the business patronymic name and to underscore its relevance for excellence-driven firms. Our study also aims to stand as a valuable contribution to the methods of identification of family-owned businesses through a direct and indirect analysis of databases and other regular sources of information.

Propositions to incorporate the patronymic business double name into research on intangible resources and familiness of family businessesIn addition to the abovementioned propositions to include the two names as variables in the methods of identification and classification of family businesses, we believe that it is necessary to investigate further on the company name as an intangible resource at the service of family branding and integrate it as a strategic issue for familiness.

Our line of argument to support these proposals is based on the fact that the double name of a family business might:

- 1.

be related to the founders’ personal or family values;

- 2.

be related to the professional values prevailing in the family business;

- 3.

serve as a sign of proactivity of the company towards internationalisation, innovation or family branding;

- 4.

be of use for other intangibles such as brand image, reputation and social responsibility;

- 5.

be an indicator of the level of professionalisation and excellence in management: when a company manages its names professionally and excellently, it means that it has achieved success at all levels of corporate management.

When a family business uses family names for its double name, this might be directed towards the founders’ values with more or less classic and traditional styles. When the double name is used as corporate name but not as brand name (‘assumed name’, henceforth), this family business has expanded and opened on the basis of the founders’ legacy, and it is more prone to change and professionalisation. Finally, when a family business does not make use of the patronymic either as corporate name or as brand name, it is a firm where more creative, groundbreaking and innovative personal and professional values prevail.

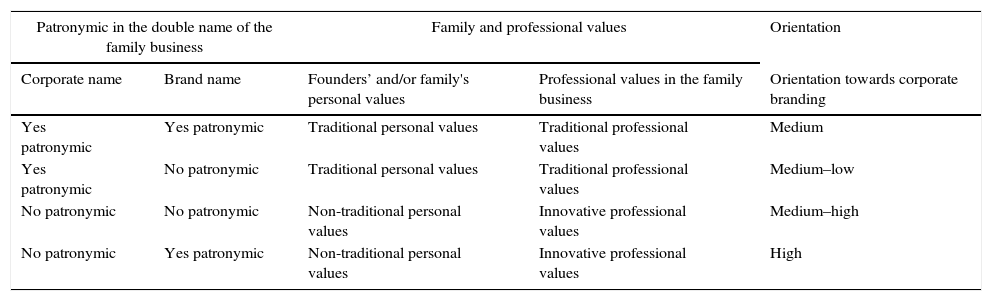

In the following classification (see Table 3), we establish a connection between the double name of the family business, the founders’ and family's values, and the company's professional values.Proposition 3.1 Founders who put their names to the company feel greater attachment to the company and delay its generational change as much as possible.

Family's and company's values and branding orientation, depending on the management of the patronymic in the double name of the family business.

| Patronymic in the double name of the family business | Family and professional values | Orientation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate name | Brand name | Founders’ and/or family's personal values | Professional values in the family business | Orientation towards corporate branding |

| Yes patronymic | Yes patronymic | Traditional personal values | Traditional professional values | Medium |

| Yes patronymic | No patronymic | Traditional personal values | Traditional professional values | Medium–low |

| No patronymic | No patronymic | Non-traditional personal values | Innovative professional values | Medium–high |

| No patronymic | Yes patronymic | Non-traditional personal values | Innovative professional values | High |

The corporate name is regarded as “the work” of the founders and of their personal values (as it is them who, on most occasions, decide the name of the family firm, rather than relying on experts at name creation).

The act of naming a business is the outcome of a process that ‘X-rays’ the personality of who decides how to do it and of who creates it. There are corporate names and ‘designators’: more or less classic, traditional or conservative, moderate, open, creative, innovative and transgressive. The name best communicates the personality and values of those who select it, keep it or change it.

Sometimes the name of the previous family owners is maintained when the firm is acquired by other family, as in the case of La Farga Lacambra, founded in Barcelona in 1808. The Lacambra family lost control of the property in 1981. Today, despite keeping the name of the founder, Lacambra, the company is a holding company owned by LFG.

Double name and social responsibility and family business reputationWhen the status of family business is not conveyed through the corporate name, it is more costly to activate and promote family brand and familiness. The US family companies whose name corresponds to the family's have a greater reputation than those which employ other naming conventions, among other things because they are more pro-active towards social responsibility (Kashmiri & Mahajan, 2010).Proposition 3.2.1 When the corporate name uses the patronymic or the family name – and this is also the trade name in the family business – the company is more likely to be perceived as a family business and to play a more proactive role in exercising its social responsibility within its sphere of influence. When the corporate name uses the patronymic or the family name – and this is also the trade name in the family business – it is more likely that the company has a positive and global impact on the engagement of the company with its stakeholders.

The degree of orientation and proactivity towards branding – and, ultimately, towards change in general – correlates with the degree of coincidence or intervention – total or partial – between the two names.Proposition 3.3.1 The relationship of the variable “corporate name” with the variable “trade name” of the company and of its products and/or services may serve as indicators of the proactivity of the company towards brand issues, and of the presence of the values of the founders of the company and the personal values of their successors.

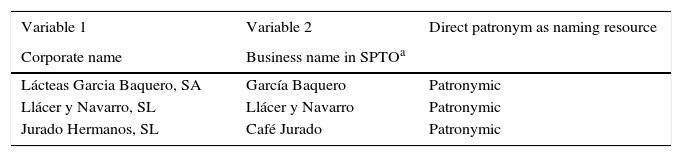

The gap between corporate and brand name may also serve as an indicator of the company's predisposition towards branding issues: the wider the gap, the greater the family firm's predisposition to boost its corporate brand and work on branding.Proposition 3.3.2 The degree of coincidence between corporate name and the brand name with which the business operates may serve as an indicator of the awareness of managers and executives and investments in brand management (seeTables 4 and 5). Continuation of the patronymic in the brand name of the family business. Continuity of the indirect patronymic in brand name of the family business. Family businesses whose trade name is an assumed name have more trademarks of products, which might indicate greater proactivity towards branding. As the family business grows and becomes more professional, there is more probability of working on the trade name or brand name of the family business (either to maintain it or modify it, with the assistance of corporate naming professionals).Variable 1

Variable 2

Direct patronym as naming resource

Corporate name

Business name in SPTOa

Lácteas Garcia Baquero, SA

García Baquero

Patronymic

Llácer y Navarro, SL

Llácer y Navarro

Patronymic

Jurado Hermanos, SL

Café Jurado

Patronymic

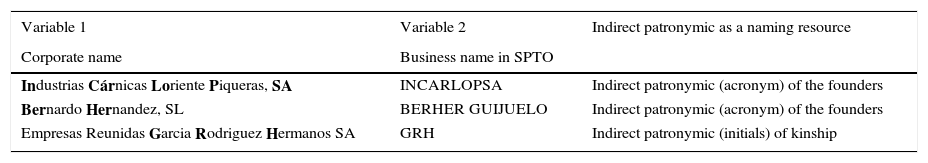

Variable 1

Variable 2

Indirect patronymic as a naming resource

Corporate name

Business name in SPTO

Industrias Cárnicas Loriente Piqueras, SA

INCARLOPSA

Indirect patronymic (acronym) of the founders

Bernardo Hernandez, SL

BERHER GUIJUELO

Indirect patronymic (acronym) of the founders

Empresas Reunidas Garcia Rodriguez Hermanos SA

GRH

Indirect patronymic (initials) of kinship

We may check this by establishing a connection between the variables “number of employees” and “operating revenues” with the difference between “corporate name” and “trade name” of the company, bearing in mind the date when the trade name of the family business is registered.Proposition 3.3.5 Family businesses whose trade name is created from the acronym or initials of the patronymic in the corporate name partly renounce to convey its family business condition.

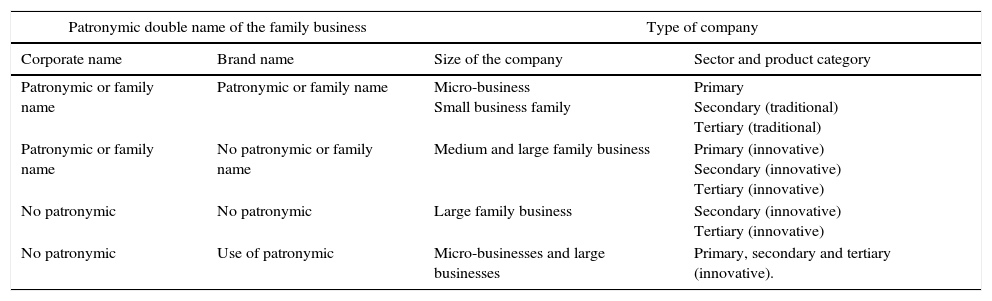

The use of the patronymic and the family names might be connected with the size of the family business. As the firm becomes more professional and increases its size and turnover, it is more likely that the family firm modifies its naming formula in its trade name (see Table 6). One further issue to be considered is the year of foundation of the family firm. If the company has a long history, then it is more probable that the company uses the patronymic.Proposition 3.4.1 The smallest the family business, the more likely it is that it uses the patronymic or family names in its corporate and brand names. The smallest the family business, the more likely it is that its corporate and brand names coincide. The largest the family business, the more likely it is that it does not use the patronymic as corporate or brand name. The largest the family business, the more likely it is that its corporate and brand names do not coincide.

Size of the company and orientation towards branding, depending on the management of the patronymic in the family business “double name”.

| Patronymic double name of the family business | Type of company | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate name | Brand name | Size of the company | Sector and product category |

| Patronymic or family name | Patronymic or family name | Micro-business Small business family | Primary Secondary (traditional) Tertiary (traditional) |

| Patronymic or family name | No patronymic or family name | Medium and large family business | Primary (innovative) Secondary (innovative) Tertiary (innovative) |

| No patronymic | No patronymic | Large family business | Secondary (innovative) Tertiary (innovative) |

| No patronymic | Use of patronymic | Micro-businesses and large businesses | Primary, secondary and tertiary (innovative). |

A recurring problem when doing research on family business is that most countries do not have specific classifications of family enterprises (Diéguez-Soto, López-Delgado, & Rojo-Ramírez, 2014; Rojo Ramírez, Diéguez Soto, & López Delgado, 2011). We must therefore turn to indirect filters of variables to find out the family nature of the companies.

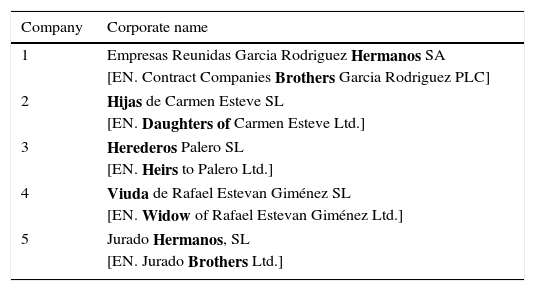

The double name and direct identification of the family nature of the companyProposition 4.1 To include the variable “corporate name” in the family business identification methods, as it can straightforwardly convey the family nature of the company and even information about the generational state. It does so by means of phrases denoting kinship (e.g. sons of, widow of, brothers, heirs, among others) in the construction of the corporate and trade names.

In English, business names ending in “-bro” (clipped from “brothers”) often denote a family enterprise (e.g. Hasbro, Umbro or Warner Bros). Some Spanish companies include the syllable “her” (as a clipped form of hermanos [EN. ‘brothers’]). Despite being a valid option to determine family condition, the truth is that relatively few companies use phrases of kinship, either directly or in the form of an acronym (see Table 7).

Corporate name as a variable in the identification and classification of the family nature of the company.

| Company | Corporate name |

|---|---|

| 1 | Empresas Reunidas Garcia Rodriguez Hermanos SA [EN. Contract Companies Brothers Garcia Rodriguez PLC] |

| 2 | Hijas de Carmen Esteve SL [EN. Daughters of Carmen Esteve Ltd.] |

| 3 | Herederos Palero SL [EN. Heirs to Palero Ltd.] |

| 4 | Viuda de Rafael Estevan Giménez SL [EN. Widow of Rafael Estevan Giménez Ltd.] |

| 5 | Jurado Hermanos, SL [EN. Jurado Brothers Ltd.] |

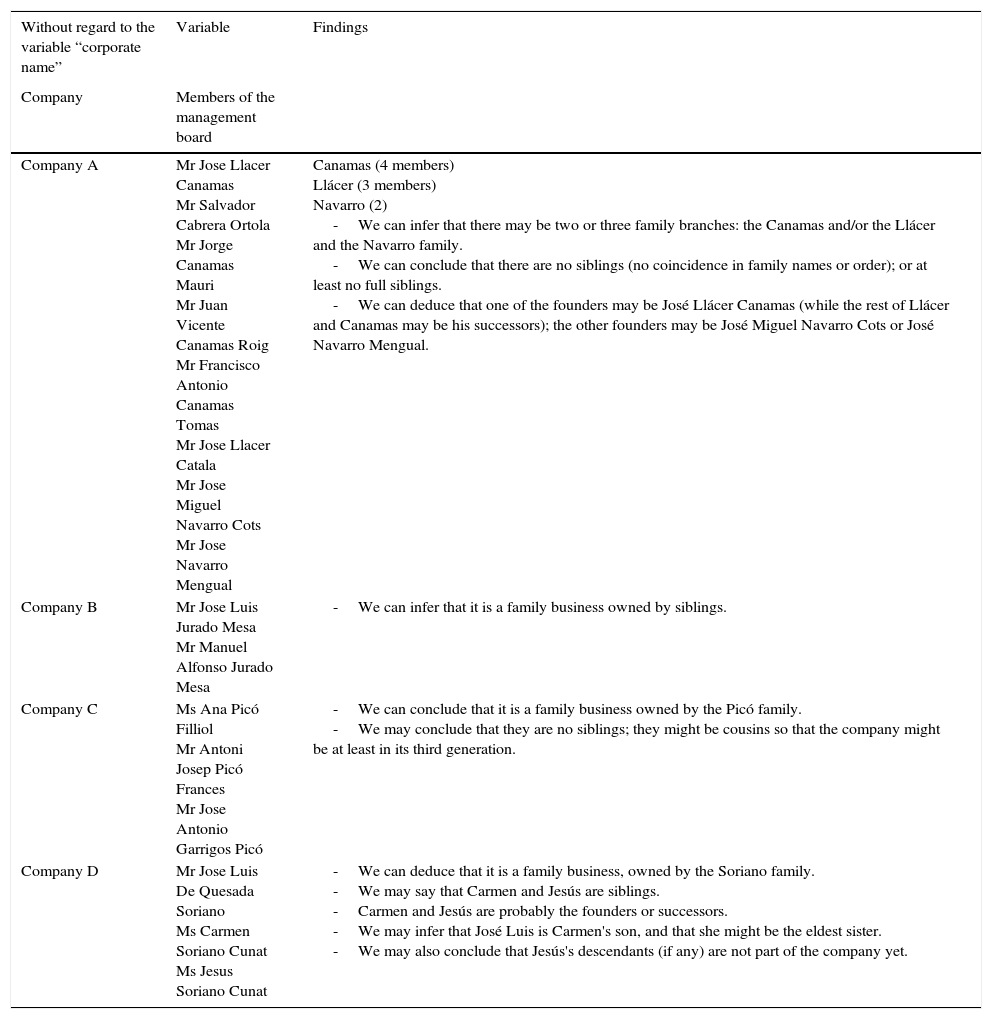

With a view to identifying and operationally classifying family businesses, some studies investigate kinship in the family names of the members of the companies’ governing bodies (in Spain, it is customary to find two [father's and mother's] surname, often in this order). In this regard, it is worth pointing out the contribution of Diéguez-Soto et al. (2014), whose work gathers some previous progress by López-Gracia and Sánchez-Andújar (2007), Gomez-Mejia, Haynes, Nunez-Nickel, Jacobson, and Moyano-Fuentes (2007) and Pérez-González (2006). Based on these contributions, Diéguez-Soto et al. (2014) distinguish 8 types of company, according to the presence of kinship and other members – through the analysis of their family names – in the management board or their role in the company (shareholder, manager and CEO). Kinship ties – and, therefore, the family nature of the enterprise – can be deduced from the coincidence, repetition and order of the family names of the members of the management board. If more than a half of the members of the management body or the shareholders share family names, it is highly probable that the company is family-owned. When there is a sole business administrator and only one name in the management board, doubt remains as to whether it is a family business or not. We must therefore consider in conjunction the stockholder structure and the senior management (see Table 8).

Identification of the family nature of the company through the family names of the members of the management board.

| Without regard to the variable “corporate name” | Variable | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Company | Members of the management board | |

| Company A | Mr Jose Llacer Canamas Mr Salvador Cabrera Ortola Mr Jorge Canamas Mauri Mr Juan Vicente Canamas Roig Mr Francisco Antonio Canamas Tomas Mr Jose Llacer Catala Mr Jose Miguel Navarro Cots Mr Jose Navarro Mengual | Canamas (4 members) Llácer (3 members) Navarro (2) -We can infer that there may be two or three family branches: the Canamas and/or the Llácer and the Navarro family. -We can conclude that there are no siblings (no coincidence in family names or order); or at least no full siblings. -We can deduce that one of the founders may be José Llácer Canamas (while the rest of Llácer and Canamas may be his successors); the other founders may be José Miguel Navarro Cots or José Navarro Mengual. |

| Company B | Mr Jose Luis Jurado Mesa Mr Manuel Alfonso Jurado Mesa | -We can infer that it is a family business owned by siblings. |

| Company C | Ms Ana Picó Filliol Mr Antoni Josep Picó Frances Mr Jose Antonio Garrigos Picó | -We can conclude that it is a family business owned by the Picó family. -We may conclude that they are no siblings; they might be cousins so that the company might be at least in its third generation. |

| Company D | Mr Jose Luis De Quesada Soriano Ms Carmen Soriano Cunat Ms Jesus Soriano Cunat | -We can deduce that it is a family business, owned by the Soriano family. -We may say that Carmen and Jesús are siblings. -Carmen and Jesús are probably the founders or successors. -We may infer that José Luis is Carmen's son, and that she might be the eldest sister. -We may also conclude that Jesús's descendants (if any) are not part of the company yet. |

We must nonetheless point to some ideas about “new family forms” to be considered by research on the identification of the family nature, stemming from the search of family ties and from the analysis of family names on the government bodies of enterprises:

- 1.

The “new family forms” are landing up at family business and they pose an added challenge to the identification of family firms through their family names. For instance, it might be the case that the management boards of family business integrate descendants of the founders’ second marriage or descendants of second spouses, among others. Family ties are starting to not being conveyed “orderly” through the family name scheme.

- 2.

The occurrence or repetition of some family names is relatively high in certain countries or regions, which might complicate the recognition of family ties in these. This circumstance might lead to misconstruing family ties (as in Spain: García, Martínez, Fernández, Hernández, López or Rodríguez).

- 3.

In those countries where the order of paternal and maternal surnames changes, the scheme must also be altered. For instance, in Portugal and Brazil descendants are given the mother's first surname. In other countries, women take their husbands’ surname when they marry. In Spain, a recent change in legislation allows now to use maternal surnames first in the descendants.

- 4.

In those countries where descendants only take one surname, the identification of family ties is even more difficult.

- 5.

When there are legal entities in the government bodies the analysis must be redirected towards the individuals that form the intermediary companies.

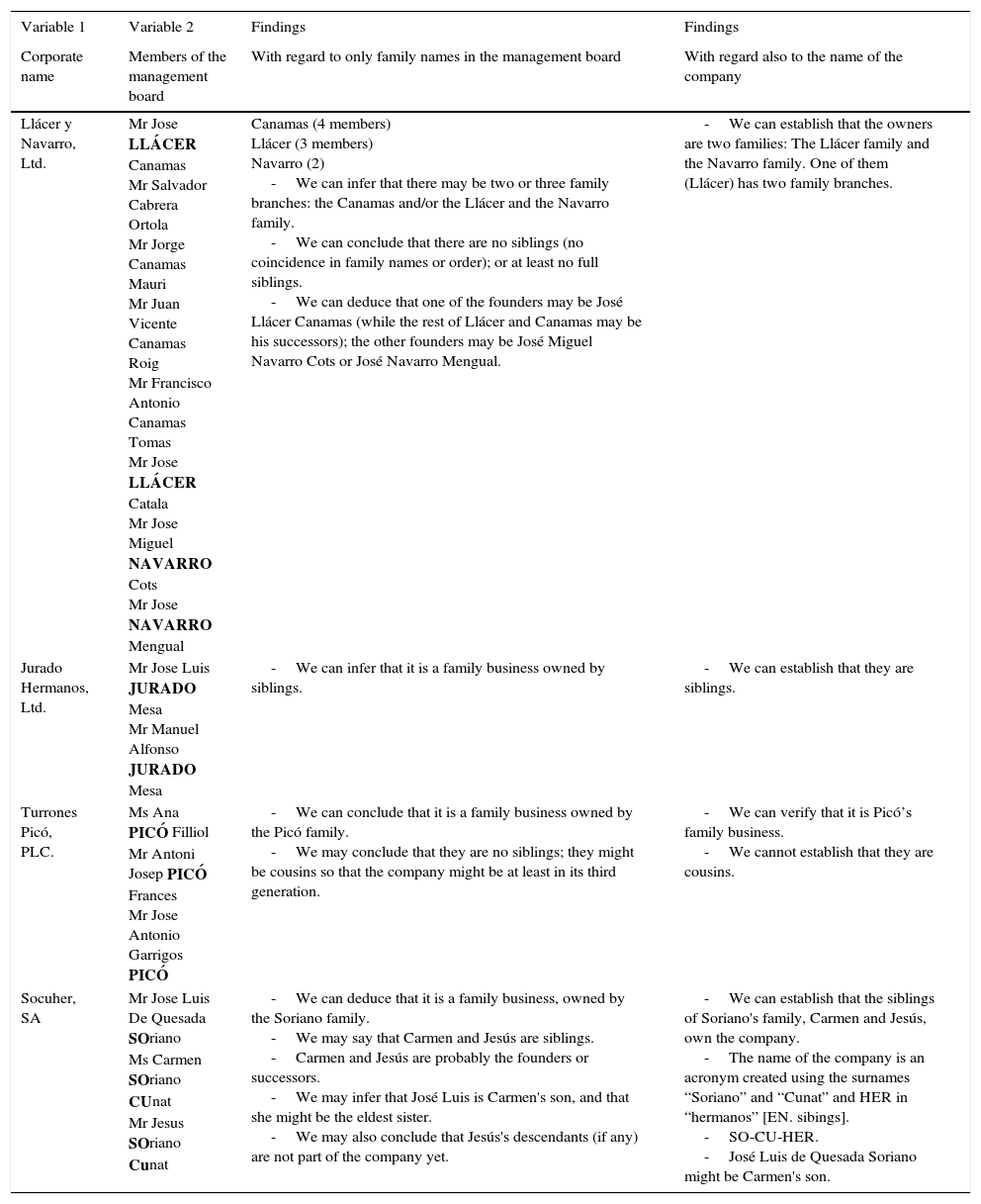

In addition to the analysis of the predominant family names in the government bodies, the examination of their direct or indirect presence (by means of initials or acronyms) in their corporate names and in their trade names increases the probability of successfully identify a family business and kinship among their government bodies (seeTables 9 and 10).

Identification of the family nature of a company through the family names of the members of its management board and through its patronymic corporate name.

| Variable 1 | Variable 2 | Findings | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate name | Members of the management board | With regard to only family names in the management board | With regard also to the name of the company |

| Llácer y Navarro, Ltd. | Mr Jose LLÁCER Canamas Mr Salvador Cabrera Ortola Mr Jorge Canamas Mauri Mr Juan Vicente Canamas Roig Mr Francisco Antonio Canamas Tomas Mr Jose LLÁCER Catala Mr Jose Miguel NAVARRO Cots Mr Jose NAVARRO Mengual | Canamas (4 members) Llácer (3 members) Navarro (2) -We can infer that there may be two or three family branches: the Canamas and/or the Llácer and the Navarro family. -We can conclude that there are no siblings (no coincidence in family names or order); or at least no full siblings. -We can deduce that one of the founders may be José Llácer Canamas (while the rest of Llácer and Canamas may be his successors); the other founders may be José Miguel Navarro Cots or José Navarro Mengual. | -We can establish that the owners are two families: The Llácer family and the Navarro family. One of them (Llácer) has two family branches. |

| Jurado Hermanos, Ltd. | Mr Jose Luis JURADO Mesa Mr Manuel Alfonso JURADO Mesa | -We can infer that it is a family business owned by siblings. | -We can establish that they are siblings. |

| Turrones Picó, PLC. | Ms Ana PICÓ Filliol Mr Antoni Josep PICÓ Frances Mr Jose Antonio Garrigos PICÓ | -We can conclude that it is a family business owned by the Picó family. -We may conclude that they are no siblings; they might be cousins so that the company might be at least in its third generation. | -We can verify that it is Picó’s family business. -We cannot establish that they are cousins. |

| Socuher, SA | Mr Jose Luis De Quesada SOriano Ms Carmen SOriano CUnat Mr Jesus SOriano Cunat | -We can deduce that it is a family business, owned by the Soriano family. -We may say that Carmen and Jesús are siblings. -Carmen and Jesús are probably the founders or successors. -We may infer that José Luis is Carmen's son, and that she might be the eldest sister. -We may also conclude that Jesús's descendants (if any) are not part of the company yet. | -We can establish that the siblings of Soriano's family, Carmen and Jesús, own the company. -The name of the company is an acronym created using the surnames “Soriano” and “Cunat” and HER in “hermanos” [EN. sibings]. -SO-CU-HER. -José Luis de Quesada Soriano might be Carmen's son. |

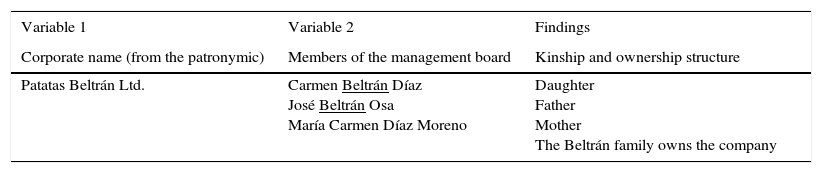

Identification of family ties through the family names of the members of the management board and the patronymic corporate name of the family business.

| Variable 1 | Variable 2 | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Corporate name (from the patronymic) | Members of the management board | Kinship and ownership structure |

| Patatas Beltrán Ltd. | Carmen Beltrán Díaz José Beltrán Osa María Carmen Díaz Moreno | Daughter Father Mother The Beltrán family owns the company |

Besides contributing to the identification of the family nature of the company, an analysis that connects the patronymic business name with the members of the management board allows us to classify the company according to its generational status and to identify its partnership structure:

- -

2nd and 3rd-generation family business: formal and ordering coincidence of family names in more than one member of the management board and of the board of directors or CEO; and use of first surname (in the case of male founder) or second surname (in the case of female founder) in the corporate or trade names (see Table 9).

- -

For the 3rd-generation family business, formal and non-ordering coincidence of family names in more than one member of the management board and in the board of directors or CEO; and direct or indirect use (acronym or initial) of the first surname (in the case of a male founder) or the second surname (in the case of a female founder) in the corporate and/or trade names of the company.

- -

To support these findings, it may be interesting to find out the year of foundation of the company.

When using the patronymic of the founders or the family names, the corporate and trade name of the family business can convey information about the distribution and ownership structure of the company.

From the arrangement – in order and form – of the words or acronyms that shape the corporate and trade names of the companies, we may establish their ownership. When there are two surnames in the corporate or trade name – one from each partner, then the first surname belongs to the main shareholder. Therefore, the order of the family name in the corporate name or in the trade name of the family business is an indication of ownership structure. Main shareholders put their family names in the first place: the order of family names in the double name of the company is therefore related to share distribution.

Sometimes maybe a matter of alphabetical order or how the order of surnames sounds best. It is not always a matter of which investor is more important.

Non-family businesses often show more freedom to choose other naming criteria for their trade name, despite using the proper names or family names of the founders. Hence:Proposition 4.2.3 When the patronymic or family names occur in the trade name, it is more likely that the company is family-owned than when it occurs in the corporate name. When the patronymic or family names occur in the trade name, it is more likely that the company is family-owned than when other naming criteria prevail (fantasy, description of activity, initials or toponym, for instance).

As we have repeatedly expressed, the name is a sign or an indication that encloses a great deal of information and that – as a variable of analysis – can play a key role in identifying family businesses.

ConclusionsThe business name is a resource of great interest for business management, given its influence and effect on the stakeholders. Naming is one of the major areas that deserve extensive research from the cross-disciplinary perspectives of management and corporate branding.

The patronymic is a highly relevant naming convention in family business. Corporate name should be integrated as an element of brand engagement or internal branding: a company whose name comes from the name of the founder or family names, could develop strategies and affective commitment and more effective internal branding.

The history or background of the corporate name can be conceived and conveyed strategically as an essential element of the corporate and family storytelling. The patronymic corporate name clearly specifies a strong link between family and company. The patronymic openly communicates ownership and commitment, which crucially effects social responsibility, confidence in the family and in the firm and their reputation. The firm name is regarded as an intangible legacy of the founders. A decision to change this name ultimately depends on the personal and professional values prevailing in the family or successors when the new generation takes over.

Besides, we believe that the corporate name is a useful variable for research on family businesses, especially in methods of identification and classification of firms of this type. It also opens new avenues of research for the analysis of the entire denominative scenario of the family business as a variable of family brand and familiness.

We underscore the opportunity cost of disregarding the strategic dimension of the name for family businesses and researchers in this field.

The corporate name can also be viewed as a sign or indicator of some issues regarding the family firm. It may be used to reveal the family nature of the company, its shareholder structure, kinship or family ties. It may also be perceived as a measure of the proactivity of the family firm towards particular strategic affairs.

This exploratory work aims to bridge the existing gap in the literature on corporate naming and family firm naming in particular.

Our research will continue with the empirical testing of the naming criteria that predominate in Spanish family businesses, of naming in family businesses at the service of general policies, of corporate branding, of brand engagement or of brand management as procedures for familiness.

The naming scenario of a family business is a kind of corporate black box that guards important information. A comprehensive study of the double name, couple with other supporting variables, may shed light (indirectly) on central features of family businesses such as the influence of the founders as corporate referents, the prevailing family values, the firm's risk aversion, and its proneness to innovation and internationalisation. Ultimately, when a family business achieves excellence in the management of its names it also reaches success at all levels.

In future research we will use the family business name as an operational variable in the methods of identification and classification in empirical investigations incorporating structural variables.

Limits and future researchAs a result of the research conducted on the links between corporate name and family business – and in particular on patronymics, we have formulated a series of propositions that might serve as a starting point for further study. We aim to turn these propositions into hypotheses and carry out some exploratory work with family businesses in Spain in order to test the validity of the aforementioned propositions.

This empirical research will allow us to reveal the prevailing naming typology in family businesses. In particular, as regards the patronymic, we aim to:

- 1.

discover its presence, typology and frequency, depending on the size of the company (micro-, medium and large family business), economic sector and year of foundation. The latter is a variable that contains information about which generation runs the company.

- 2.

attempt to measure the impact and influence of the patronymic corporate name on the human resources of the family business and on the members of the business family. Our hypothesis is that the patronymic business name, when appropriately managed, favours brand management internally – in the collaborators and family members – and externally – in the consumers and other stakeholders. In this future study, we will continue exploring the link between the corporate name and the proper names of the members of the management board of the family business, which will contribute to highlighting the relevance of the corporate name as an essential intangible resource of familiness and of reputational feedback of the family business.

It might also be interesting to compare family businesses using patronymics with those using other denominative criteria (mainly toponyms, descriptive names, creative names and contracted forms). It might also be relevant to contrast the naming realities of family and non-family businesses. The most obvious and significant differences between these types of companies will be sufficiently accounted for in terms of familiness.

From the perspective of family branding, we might analyse the entire naming scenario of family business corporate or product and service brands, with a view to establishing a relationship with patrimonial arrangement and brand architecture.

A longitudinal analysis of data would disclose the naming tendencies of family businesses over time. This study would also allow us to appraise the perception and effects of particular naming variants on the stakeholders, especially on executives and non-family members, capital markets and clients.

We must also further in the theoretical and empirical consolidation of corporate naming as a field at the service of the brand and of the reputation of the business family and the family firm, and explore its contribution to familiness. We must go deep into the difference between product naming, corporate naming and the specificity of the family business name.

Thus, we believe that it is necessary to provide tests and empirical analyses on:

- –

The economic contribution of the corporate name to the corporate brand values.

- –

The opportunity cost of a patently inappropriate name for semantic or strategic reasons.

- –

The impact of the brand name – of products and services and of the family business – in terms of effectiveness, renown and memory.

- –

The relationship between verbal identity – names – and the visual identity of family businesses.

- –

The connection between corporate naming and the naming of products and/or services.

- –

The psychology and creativity of family entrepreneurs and founders of SMEs and large companies through the name they give to their companies. It might be of great interest to learn about the founders’ rationale as “designators”, their motivations and their possible agreements and pacts for naming the company. Because to date it is business founders to a greater extent who give names to their family firms. Learning about their psychology, motivations, values, commitment to the (social) environment, level of self-esteem, and need for recognition will undoubtedly help us to understand the motivation behind a particular name. Although neurobranding tools would be appropriate for this, the difficulty lies in the access to the entrepreneurs.

- –

The correlation between the naming solutions of family businesses and the strategic impact on business family members, executives, workers and clients.

- –

The conditions and justifications for a change of name in family businesses: What strategic factors have an influence on a potential change of name in a family business?

- –

Test the semantic and operative validity of family surnames with negative associations/connotations (as for instance, in Spain: Matajudíos, Matamoros, Negrero, Hurraca, Daño, Perro, Burro, Matador, Tripas, Guerra, Infierno, Malo, etc.) and establish alternative naming criteria in such cases.

This alternative line of research would provide new ingredients and a new impetus to a type of analysis which has not been much researched in relation to family businesses. Which are the genuine reasons that influence the final decision-making to select the corporate name and brand name in family-owned businesses? Some of the reasons might be the following: to resort to customs, traditions and the sector inertia; to give more prominence to the founders (to the detriment of the stakeholders); to prefer classic naming solutions to more innovative ones, etc.

The theoretical relations we have proposed in this work – in addition to the proposals we have formulated from our inductive evidence – and once established in the form of inferences and contrast of hypotheses, will represent decisive steps towards an awareness of the strategic potential of the corporate name.

Definitely, this future research will bring new and relevant findings for corporate name, family branding and brand management, and will also favour the activation of this intangible issue (i.e. corporate name) as an important strategic element at the service of investigation and management of familiness.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.