To describe the quality of sleep of patients undergoing cardiac surgery during the first two nights following surgery and identify some of the factors conditioning the nightly rest of these patients in the Intensive Care Unit.

MethodObservational descriptive study based on applying the Richards–Campbell Sleep Questionnaire through a consecutive sample of patients undergoing cardiac surgery with Intensive Care Unit admission. Simultaneously, a questionnaire assessing different environmental factors existing in the unit as possible conditioning of the night's rest was applied. The association between consumption of opioid and sleep quality was studied.

ResultsSample of 66 patients with a mean age of 65±11.57 years, of which 73% were men (N=48). The Richards–Campbell Sleep Questionnaire garnered average scores of 50.33mm (1st night) and 53.30mm (2nd night). The main sleep disturbing factors were discomfort with the different devices, 30.91mm and pain, 30.18mm. The problems caused by environmental noise, 27.5mm or through the voices of the professionals, 26.53mm were also elements of nocturnal discomfort. No statistical association was found between sleep and the distance of the patient with respect to the nursing control area or related to opioid analgesics.

ConclusionsThe quality of sleep during the first two nights of Intensive Care Unit admission was “regular”. The environmental factors that conditioned the night-time rest of patients were discomfort, pain and ambient noise.

Describir la calidad del sueño de los pacientes sometidos a cirugía cardiaca durante las dos primeras noches de postoperatorio e identificar algunos de los factores condicionantes del descanso nocturno de estos pacientes en la Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos.

MétodoEstudio descriptivo observacional basado en la aplicación del Cuestionario del Sueño de Richards-Campbell mediante un muestreo consecutivo de pacientes sometidos a cirugía cardiaca con ingreso en Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos. Simultáneamente se aplicó un cuestionario que evaluaba diferentes factores ambientales existentes en la unidad como posibles condicionantes del descanso nocturno. Se estudió la asociación entre el consumo de opiáceos y la calidad del sueño.

ResultadosMuestra de 66 pacientes con edad media de 65±11,57 años, de los cuales el 73% eran hombres (N=48). El Cuestionario del Sueño de Richards-Campbell obtuvo una puntuación media de 50,33mm (1.a noche) y 53,30mm (2.a noche). Los principales factores perturbadores del sueño fueron el malestar con los diferentes dispositivos 30,91mm y el dolor 30,18mm. Los problemas generados por el ruido ambiental 27,5mm o bien a través de las voces de los profesionales 26,53mm también resultaron elementos de molestia nocturna. No se encontró asociación estadística entre el sueño y la distancia del box del paciente respecto al control de enfermería ni en relación con el consumo de analgésicos opiáceos.

ConclusionesLa calidad del sueño durante las dos primeras noches de ingreso en Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos fue «regular». Los factores ambientales que más condicionaron el descanso nocturno de los pacientes fueron el malestar, el dolor y el ruido ambiental.

This study provides the original results of a research carried out on a homogeneous sample of patients (exclusively patients who underwent heart surgery following the same surgical, anesthetic and postoperative protocol) (N=66 patients) and is related to a prevalent problem in polyvalent and postsurgical intensive care units (ICUs): the inadequate duration and quality of the sleep of patients admitted to the ICU during their postoperative period.

Although some studies have already assessed the sleep of patients staying at ICUs, only some specify the results of patients treated exclusively with heart surgery. The available literature states that, after undergoing surgery, patients’ sleep tends to be of poor quality, light and with frequent awakenings, mainly due to the postsurgical pain and the units’ ambient sounds. In addition to assessing patients’ quality of sleep, this study analyzes other environmental and intrinsic factors of the surgical procedure itself, which had already been identified in previous research studies.

Given the scarcity of research studies providing original data assessed through an objective and reliable tool, such as the Sleep Questionnaire that we used for this study, we believe that our study will be of particular interest to our professional group.

Implications of the studyThe results of our study allow for expanding our knowledge on the sleep of conscious patients admitted to intensive care units after undergoing heart surgery. Identifying the main factors that interrupt and difficult patients’ sleep is the first step to attempt to apply corrective measures, which according to our results should be: improve well-being, optimize analgesia and minimize, as far as possible, the ambient noise generated by alarms and monitoring equipment, as well as by the staff working during the night shift.

Sleep is defined as a “necessary and restorative physiological state, normally periodic and reversible, characterized by depressed senses, consciousness and spontaneous motility, in which the individual can awaken with sensory stimuli”.1 It is assigned properties such as the homeostatic restoration of the central nervous system and other tissues, conservation of energy, elimination of irrelevant memories and preservation of perceptive memory. Furthermore, it is involved in the regulation of physiological processes with proven circadian variability, such as body temperature control, hormonal secretion (cortisol), the tone of the smooth muscle of bronchi and arteries, consequently affecting the heart rate, as well as on systemic and coronary perfusion, and on the immune system.2–4

There are two different sleep stages: the rapid eye movements (REM phase or paradoxical sleep) phase and the slow wave sleep (non-REM phase). The non-REM phase is comprised by four stages, according to the depth of sleep. Stages 1 and 2 correspond to light sleep, whereas stages 3 and 4 correspond to deep sleep. Sleep begins with the non-REM phase I and progresses until reaching phase IV, returning to phase III, from there to phase II, finally giving way to the REM phase. This progression from one stage to another constitutes a 90-min cycle, which is repeated twice prior to continuing with cycles in which non-REM phases III and IV disappear progressively while the REM phase increases gradually, so that a full 8-h sleep period may be comprised by 4–6 cycles. When individuals wake up during any of the phases of these cycles, their rest is interrupted and they have to fall asleep once again starting by the first non-REM stage. REM sleep, which accounts for 20–25% of the total sleep period, is linked to individuals’ emotional and psychic rest, whereas non-REM sleep is associated with the organism's physical restoration.3–9

The available literature reports that in severely ill patients, the REM phase accounts for 6% of the total sleep duration, with non-REM phases III and IV being less frequent. Moreover, these patients tend to experience frequent awakenings and sleep fragmentation. Some research groups have tried to explain the close interrelation between sleep processes and overall physical, psychological and behavioral health, concluding that the lack of restorative sleep may delay a disease's recovery process.3–8

However, the sleep of patients admitted to Intensive Care Units (ICU) is one of the least studied dimensions by professionals who work in them, probably owing to the fact that they assume with certain degree of conformity that poor quality sleep and lack of sleep is frequent among conscious patients who are admitted to such units.7,8 To factors resulting from the disease itself, such as pain, immobility, provision of nursing care, etc., we must add both the structural (open units with almost no natural light or privacy in some cases) and the environmental (noise, excessive artificial light, etc.) which characterize most intensive care unit. In their respective research studies, Nicolás et al.,7 Gómez8 and Redeker et al.10 analyzed several factors that interrupted patients’ sleep during their stay at an ICU, identifying noise, lights, discomfort, pain, continuous care administered by the nursing staff and the postsurgical intake of opioids as the main causative factors. In the specific case of patients subjected to heart surgery, the available literature states that over 50% of patients reported having poor quality sleep, with frequent interruptions and irregular sleep cycles during their stay at the ICU.10–13

Motivated by the appeal of this matter, and particularly by the lack of prior research experiences in this field in the unit under study, we set ourselves the following objectives.

Objectives- •

To describe the sleep quality of patients during their first two nights of admission to an ICU after undergoing heart surgery.

- •

To identify and quantify the main conditioning factors of sleep.

- ∘

Individual characteristics.

- ∘

Environmental factors.

- ∘

Use of opioid analgesics.

- ∘

Observational, descriptive and cross-sectional study evaluating the sleep quality of patients who underwent heart surgery with extracorporeal circulation during their first two nights of admission to an ICU. Only the first two nights of admission to the ICU were studied, given that this is the usual length of stay for postoperative patients who do not experience postsurgical complications, and also owing to the fact that this allowed for obtaining the most homogeneous patient sample possible from a medical-surgical point of view.

To carry out this study we obtained the relevant permits from the Directorate and from the hospital's Clinical Research Ethics Committee.

Scope of studyTertiary reference hospital for cardiovascular surgical pathology in the region, with a polyvalent ICU unit with a lineal distribution of 20 available boxes. Patients subjected to heart surgery are admitted to the “small” wing of the unit, between boxes 11 and 18, under the supervision of nursing control unit 2.

Study subjectsInclusion criteriaConsecutive sampling was carried out between February 2008 and January 2009 to enroll patients admitted to an ICU after undergoing heart surgery with an extracorporeal circulation pump (valve replacement, coronary revascularization, or both) who voluntarily agreed to participate in the study by signing the corresponding informed consent.

Exclusion criteria- •

Age less than 18 years.

- •

Refused to participate in the study.

- •

Usual medical prescription of hypnotics or sleep inducers.

- •

Presence of confusional syndrome during the first night of admission to the ICU, based on the results of the Confusion Assessment Method for delirium.

- •

Mental alteration, cognitive and/or sensory deficit hampering the correct application of the questionnaire.

- •

Connection to mechanical ventilation for over 24h, since the first assessable night would be at least 24h after the intervention and the results would vary according to the time elapsed.

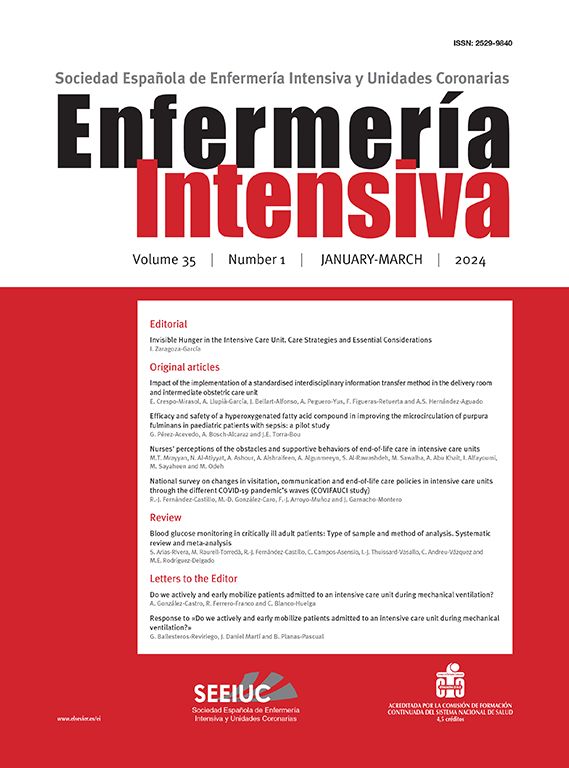

To obtain information related to the sleep quality of these patients, we used a questionnaire divided into two sections. The first section was the Richards–Campbell Sleep Questionnaire (RCSQ),14 in its version translated into Spanish by Nicolás et al.7 (Fig. 1).

This is a brief questionnaire consisting of five items constructed in the form of a visual analogue scale, in which the scores for each item are marked on a 100-mm rule, with 0mm corresponding to poor sleep and 100mm corresponding to optimal sleep. The total score was calculated by dividing the resulting sum of the score of five items by five. Sleep (between 23:00h and 7:00h of the following day) was rated as bad when the patients scored between 0–33mm, poor when the final result ranged from 34 to 66mm and good if they scored between 67 and 100mm. This is a validated test with a high reliability (Cronbach's alpha: 0.91) and internal validity (item-total correlation scores between 0.48 and 0.96), as stated by its authors.14 Its applicability and usefulness have already been proven on the surgical population of intensive care units.7,14

Simultaneously with the RCSQ questionnaire, we applied a second self-elaborated questionnaire and the same rating scale specifically designed for such purpose (its feasibility and validity was not assessed in this study) based on environmental and intrinsic factors to the surgery itself previously identified by other researches as the main causes of sleep disruption4–8: postsurgical pain, malaise secondary to the devices used, ambient noise, staffs’ voices, artificial light, presence of nearby patients and nursing interventions. Reproducing the same system as that of the Richards–Campbell Questionnaire, the patient must assign a numerical value to each item, with 0 being the minimum value, which in this case refers to the fact that this factor did not impact the patients’ sleep in any way, and the maximum value referring to unbearable annoyances.

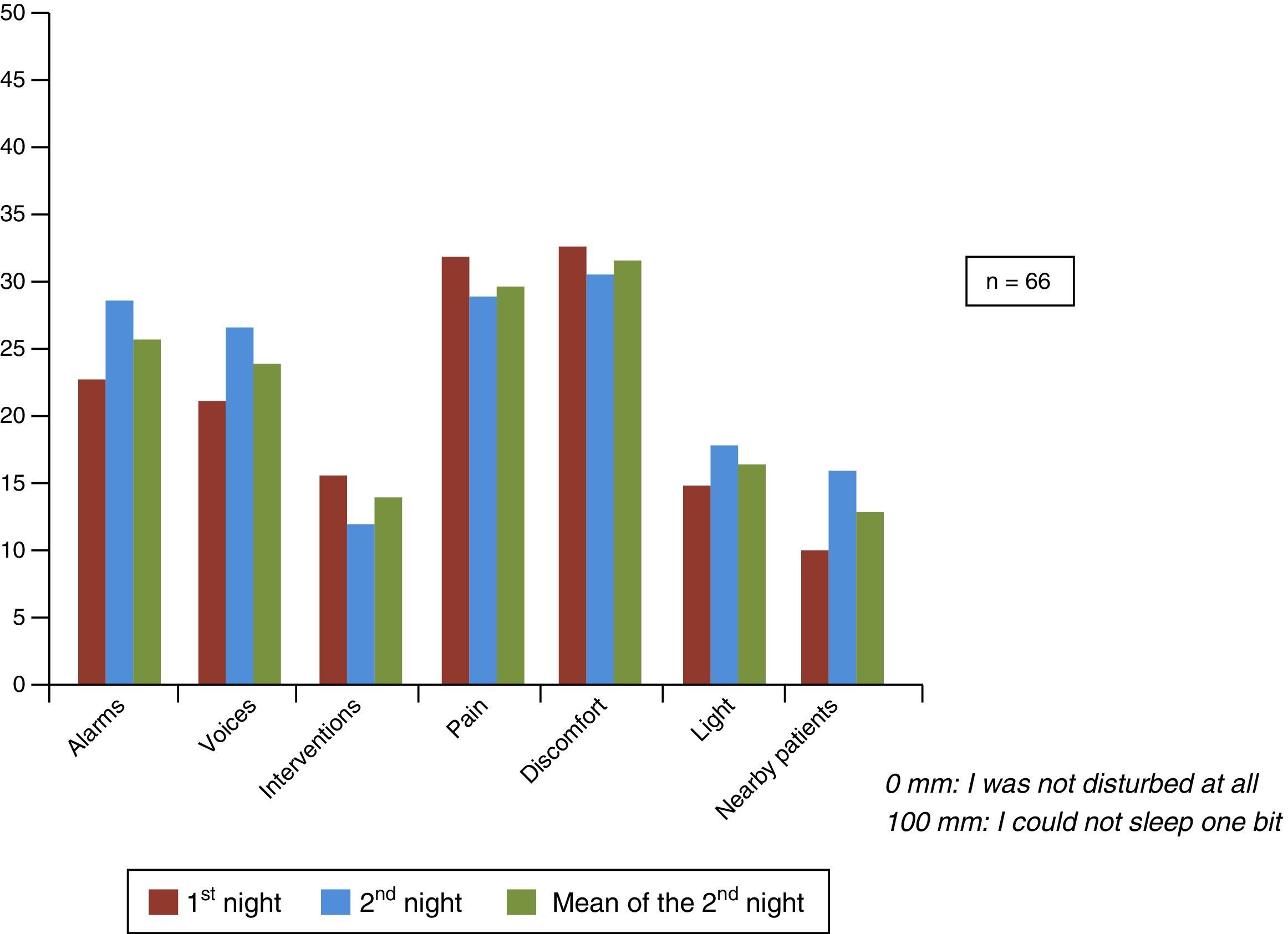

Other variables studied as potential sleep conditioning factors were the distance of the patients’ beds from the nursing control unit and the intake of opioid analgesics after the patient was disconnected from mechanical ventilation. To study the possible relationship between the distance of the patients’ beds from the nursing control unit, three different patient groups were studied according to the distance between their bed and the nursing control unit. The first group included patients whose beds were located a at a distance of less than 5.50m from the nursing control unit, the second group included those whose beds were located at a distance of 5.50–10m from the unit, and the last group included the farthest beds, located at a distance of over 10m from the nursing control unit.

For the intake of opioid analgesics, we took into account the dose of morphine hydrochloride (mg) administered to the patients since the moment they were disconnected from mechanical ventilation (day 0) until 8:00h of day 2 of their stay at the ICU (after the second night assessed).

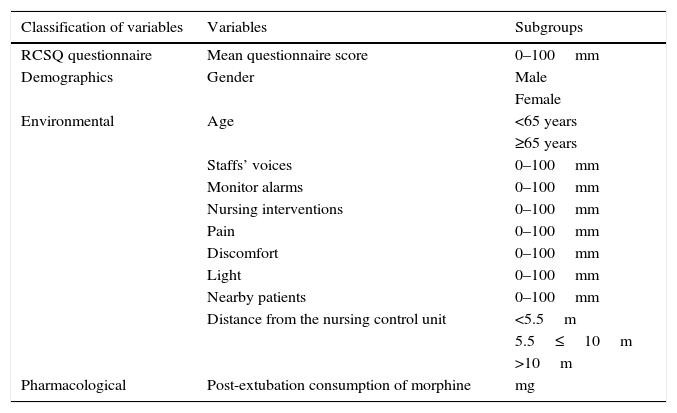

After carrying out an exhaustive bibliographic review, previous scientific publications included in the databases of MEDLINE (Pubmed), The Cochrane Library, CUIDEN and SciELO, as well as in other web platforms such as the Web of Science, the study variables were defined according to the relevant terms (Table 1).

Study variables.

| Classification of variables | Variables | Subgroups |

|---|---|---|

| RCSQ questionnaire | Mean questionnaire score | 0–100mm |

| Demographics | Gender | Male |

| Female | ||

| Environmental | Age | <65 years |

| ≥65 years | ||

| Staffs’ voices | 0–100mm | |

| Monitor alarms | 0–100mm | |

| Nursing interventions | 0–100mm | |

| Pain | 0–100mm | |

| Discomfort | 0–100mm | |

| Light | 0–100mm | |

| Nearby patients | 0–100mm | |

| Distance from the nursing control unit | <5.5m | |

| 5.5≤10m | ||

| >10m | ||

| Pharmacological | Post-extubation consumption of morphine | mg |

Data was collected by means of the application of a structured questionnaire the first morning (at 9:00h) following the patients’ second night of admission to the ICU. Said questionnaire was comprised by two sections: the first section included the aforementioned RCSQ questionnaire which allowed for quantifying the characteristics of the patients’ sleep the previous night by means of a millimetric numerical visual scale ranging from 0 to 100mm, and a second section which, by reproducing the numerical visual scale system, quantified each of the potential sleep disrupting factors identified by the patients.

After digitalizing the results of the questionnaires, the statistical analysis was carried out using the Student-t, ANOVA, U Mann–Whitney or Kruskall–Wallis tests for independent samples, depending on whether or not the data met normality criteria, in the case of quantitative variables. The potential relationship between quantitative variables was studied with linear regression models.

Data of the quantitative variables were represented on the basis of their mean and standard deviation. On the other hand, qualitative variables were represented with an N value and/or their corresponding percentage. The accepted level of statistical significance was p<0.05.

The statistical software package used was SPSS 15.0 for Windows.

ResultsThe number of patients who completed the study over the two nights and who made up our study sample was 66, of which 73% were men (N=48) and 27% women (N=18), with ages ranging from 25 to 83 years (mean 65±11.57 years). The most frequent type of intervention was valve replacement (N=32), followed by coronary bypass in 41% (N=27) of patients and other types of interventions (mixed valve and coronary surgery, myxomectomies, congenital malformations, etc.) in 11% (N=7) of patients.

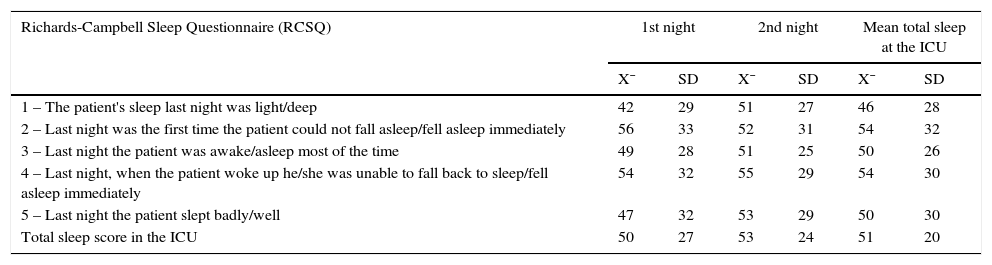

The results of the RCSQ questionnaire concerning patients’ quality of sleep during the first two nights of admission to the ICU revealed a mean score after the first night of 50±27mm and 53±24mm after the second night, with a global mean score of 51±20mm. Table 2 shows the mean scores of each item of the RCSQ over the two nights assessed.

Score of the results obtained in the Richards–Campbell Sleep Questionnaire.

| Richards-Campbell Sleep Questionnaire (RCSQ) | 1st night | 2nd night | Mean total sleep at the ICU | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X¯ | SD | X¯ | SD | X¯ | SD | |

| 1 – The patient's sleep last night was light/deep | 42 | 29 | 51 | 27 | 46 | 28 |

| 2 – Last night was the first time the patient could not fall asleep/fell asleep immediately | 56 | 33 | 52 | 31 | 54 | 32 |

| 3 – Last night the patient was awake/asleep most of the time | 49 | 28 | 51 | 25 | 50 | 26 |

| 4 – Last night, when the patient woke up he/she was unable to fall back to sleep/fell asleep immediately | 54 | 32 | 55 | 29 | 54 | 30 |

| 5 – Last night the patient slept badly/well | 47 | 32 | 53 | 29 | 50 | 30 |

| Total sleep score in the ICU | 50 | 27 | 53 | 24 | 51 | 20 |

During the first night of admission to the ICU, the highest score was recorded for item “initial sleep onset”, and the lowest score corresponded to “depth of sleep”. On the contrary, during the second night of admission, item “time spent awake” of the questionnaire obtained the highest score among all patients. However, the lowest score of that night corresponded once again to item “depth of sleep”, with item “number of awakenings” being scored equally negative.

By studying the mean scores of patients’ overall sleep during their stay at the ICU, we observed that during the two nights of the study, item “depth of sleep” obtained the lowest score. The highest score was assigned to items “initial sleep onset” and “time spent awake”.

According to the total scores obtained, the previous classification defined by the RCSQ indicated that during their first night of admission, 31.8% (N=21) of patients slept badly, 33.3% (N=22) slept poorly and 34.8% (N=23) slept well. During their second night of admission, 19.7% (N=13) of patients slept badly, 43.9% (N=29) slept poorly and 36.4% (N=24) slept well.

After ending the monitoring period comprised by the first two nights of the postoperative period, we saw that 25.75% (N=17) of patients slept badly, 38.6% (N=25) slept poorly and 35.6% (N=24) slept well.

Considering in the first place the score obtained in the RCSQ questionnaire according to the patients’ gender, the mean score obtained during the first night by women was 57±26mm versus 47±28mm in men, and 56±27mm versus 52±24mm in men during the second night. Nevertheless, this difference was not statistically significant. Patients aged 65 years or older reported a higher score in the RCSQ questionnaire only during their first night at the ICU, whereas patients aged under 65 years old reported a better sleep quality during the second night. During the first night at the ICU, the mean score reached by patients aged 65 years or older was 61±24mm, versus 43±27mm in patients younger than 65 years old (p=0.019).

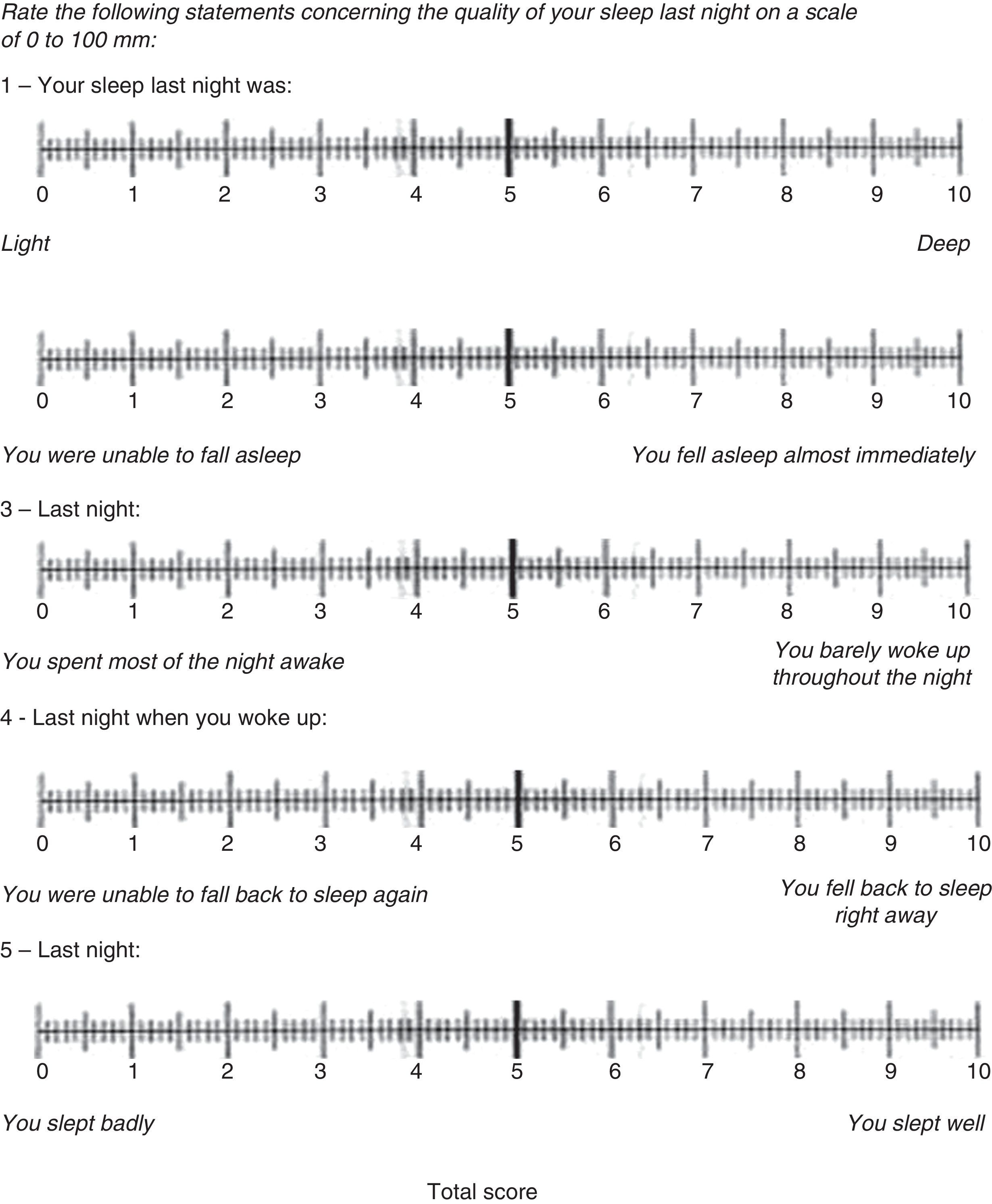

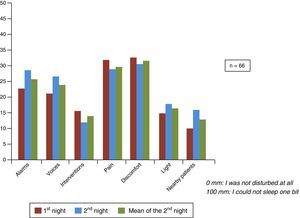

Also, during the first night at the ICU, discomfort 33±31mm and pain 32±33mm were the sleep disrupting factors with the highest scores, followed by monitor alarms 23±27mm and the staffs’ voices 21±29mm. Those factors causing a lesser impact on nighttime sleep were nursing care 16±22mm, ambient light 15±24mm and, lastly, the proximity of other patients 10±20mm. The same pattern was seen to repeat itself during the second night, with discomfort 31±30mm and pain 29±29mm being the most prevalent factors, followed by the noise of monitor alarms 29±27mm, the staff's voices 27±28mm, the presence of permanent ambient light 18±21mm, the proximity of other patients 16±27mm and, lastly, the nursing interventions 12±18mm. Fig. 2 shows the scores obtained for each environmental factor analyzed per night.

The last environmental factor analyzed was the distance between the patients’ beds and the nursing control unit, according to the three different patient groups established. The mean score of the first group in the RCSQ questionnaire (distance between the patients’ beds and the nursing control unit<5.50m) was x¯ 54±25mm, followed by a score of x¯ 50±19mm in the second group (distance between the patients’ beds and the nursing control unit of 5.50≤10m, and x¯ 52±20mm in the third group (distance between the patients’ beds and the nursing control unit>10m). No statistically significant differences were observed between either group of patients based on the distance between their beds and the nursing control unit. After analyzing each sleep conditioning factor in these patients based on the distance between their bed and the nursing control unit, we saw that in patients whose beds were located at a distance of less than 5.50m from the nursing control unit, the factors that most impacted their nighttime sleep were the staffs’ voicesx¯ 25±20mm, their painx¯ 21±27mm and the noise of the monitor alarmsx¯ 18±21mm. Contrarily, the factors that caused the least interruptions in the sleep of the patients of this first group were the proximity of other patientsx¯ 6±13mm and ambient light/temperaturex¯ 12±16mm.

As for the patients’ whose beds were located at a distance of between 5.50 and 10m from the nursing control unit, the main factors that impacted their sleep were discomfortx¯ 40±24mm, noise of the monitor alarmsx¯ 38±22mm, the staffs’ voicesx¯ 36±27mm and, lastly, the nursing interventionsx¯ 21±16mm.

However, according to patients whose beds were located a distance greater than 10m from the nursing control unit, the most annoying factor during their nighttime rest was their painx¯ 41±26mm, followed by discomfortx¯ 31±25mm. In this group of patients, the factors that had the least impact on their rest were the proximity of other patients and x¯ 7±15mm the nursing interventionsx¯ 10±11mm (Fig. 3).

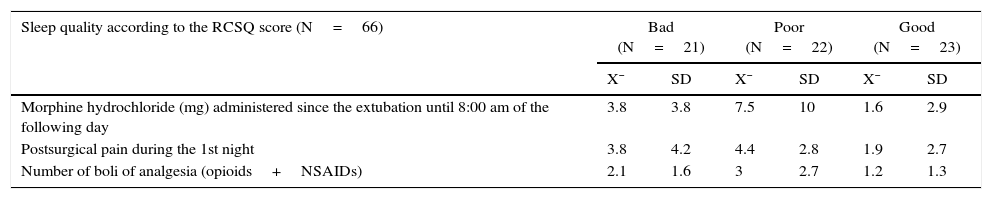

The consumption of morphine as a postoperative analgesic described in Table 3 does not establish any statistical significance between the different groups nor a linear relationship pattern between the consumption of morphine hydrochloride and the quality of the patients’ postsurgical sleep (r=0.087).

Pain, opiates and sleep quality in the ICU.

| Sleep quality according to the RCSQ score (N=66) | Bad (N=21) | Poor (N=22) | Good (N=23) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X¯ | SD | X¯ | SD | X¯ | SD | |

| Morphine hydrochloride (mg) administered since the extubation until 8:00 am of the following day | 3.8 | 3.8 | 7.5 | 10 | 1.6 | 2.9 |

| Postsurgical pain during the 1st night | 3.8 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 2.7 |

| Number of boli of analgesia (opioids+NSAIDs) | 2.1 | 1.6 | 3 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

After analyzing the scores obtained in the RCSQ questionnaire, we can point out that the patients included in our study characterized their sleep as poor, with a quick initial sleep onset, frequent awakenings and a quick sleep onset after these. Our patients claimed that their depth of sleep was the most affected factor, even though they were capable of quickly falling back to sleep again. Also, during their second night at the ICU, they mostly reported having slept lightly, with frequent awakenings, although they were capable of quickly falling back to sleep again after these. The study carried out by Nicolás et al.7 reported similar results to ours, with initial sleep onset and sleep onset after the frequent nighttime awakenings being the most highly rated factors among these patients. In both groups, the lowest score was given to the number of nighttime awakenings.

Similarly, neither the study carried out by Nicolás et al.7 nor ours confirmed that postoperative sleep may be modified by individual variables such as gender and age, as the existence of statistical significance found only during the first night, proving that patients aged 65 years and older had a better quality sleep than patients younger than 65, was a casual finding or was associated with factors related to age which are difficult to determine altogether (pain, anxiety, etc.), considering that the results varied significantly during the second night and no longer had a significant association.

With regard to the factors that impacted the patients’ sleep quality, the pain and discomfort caused by the different monitoring devices, drainages and the foreign bed, among others, were the main factors that, according to the patients, disrupted their nighttime sleep during their first two nights of stay at the ICU. Also, during the second night, the noise of the monitor alarms or devices was given the same impact score as pain. However, during the first night, this factor ranked third among all factors impacting the patients’ sleep. The noise caused by the staffs’ voices also ranked high during both nights, but still falling behind the other abovementioned factors. By grouping these last two factors in ICU noise sources, we can conclude that the third factor that most impacted the patients’ sleep was ambient noise. The least sleep disturbing factors, with the lowest scores arranged in decreasing order, were: ambient light, nursing interventions and proximity of other patients.

Also, the results of our study are similar to those previous investigations reflecting how pain is the main determinant of the quality of postoperative sleep9,12,15 and identifying noise from monitor alarms as the environmental factor causing the most interruptions in patients’ sleep.9 Noise is frequently mentioned as a sleep disrupting factor in the available literature16–20 and its impact on the stress that it can cause patients, resulting in sympathetic stimulation and overarousal, which are not beneficial for the recovery of cardiac patients, should not be underestimated.6 The World Health Organization indicates that noise levels within hospital settings should not exceed 30dB at night in order to avoid sleep disturbances. However, in practice, these levels can reach 50–70dB (comparable to the noise levels of a work office)9,12,21 at certain times and in specific areas (pharmacy, nursing control unit, etc.). In our unit with a linear distribution of patients, the area with the greatest number of unsuitable environmental factors for nighttime rest was seen to be the nursing control unit (central monitoring alarms and staffs’ voices), which is located adjacent to the pharmacy unit (artificial light and noise during the loading of medication). Nevertheless, the fact that patients’ sleep is influenced by multiple extra-environmental factors becomes evident when segregating these patients into groups with similar environmental conditions according to the distance of their beds with respect to the nursing control unit. In our study, we found that patients whose bed was located at a distance of less than 5.50m from the nursing control unit had better quality sleep during their first two nights of stay at the ICU. However, the second group of patients who reported a better quality of sleep were those whose beds were located at more than 10m from the nursing control unit. Patients whose beds were located at an intermediate distance (5.50≤10m) reported a lower score. Therefore, we were unable to establish a proportionality relation of patients’ sleep quality as a function of the distance of their beds from areas with lower environmental levels of noise and artificial light. We did confirm that patients whose beds were located further away from the nursing control units reported pain and discomfort as the main responsible factors for their lack of nighttime rest; parameters that should be similar in all the unit's beds. In fact, pain was the only factor that increased progressively for each group of beds located further away from the nursing control unit. These results could suggest that there is a certain lack of attention on behalf of the night shift staff to alleviate patients’ pain and discomfort with the necessary analgesic and well-being measures. However, although we could not validate this hypothesis due to the lack of sufficient information for its individualization per patient (boli of analgesia administered, number of postural changes throughout the night, etc.), we believe that this result is relevant.

Regarding environmental factors, it seems logical to observe how patients whose bed was located close to the nursing control unit (<5.50m) during their first two nights of stay at the ICU, stated that what most interfered with their nighttime sleep were the voices of the units’ staff. As in our case, several investigators corroborate that patients whose bed was located the nearest to the nursing control unit have the most complaints about the noise caused by the conversations held among nurses.5,7,15,20,21 However, unlike our study in which we did not find significant differences according to the distance of the patients’ bed from the nursing control unit, several other studies state that artificial light also has a significant impact on patients’ nighttime rest, as the exposure to light in the ICU may impact their ability to differentiate between nighttime and daytime, consequently contributing to a loss of the wake-sleep circadian rhythm. As a result, patients sleep a lot during the day, which favors their frequent awakenings throughout the night.6,7 In fact, a study published in 2004 by the Intensive Care Medicine journal revealed that almost half of the hours of sleep in critically ill patients took place during the daytime.5

Patients who were included in the study had been subjected to interventions in which a sternotomy had to be carried out in all cases. Given that this procedure causes intense levels of pain during the immediate postoperative period, patients tend to require opioid analgesics in order to achieve certain degree of pain relief, given their analgesic power and speed of action. However, this beneficial effect contrasts with the results obtained in several studies carried out by different researches, which indicate that the levels of morphine chloride decrease during non-REM phases III and IV, and the REM phase of sleep, potentially causing patients to wake up more frequently and have a lighter sleep.3,5,7 To this end, the current recommendation would be to suspend the use of opioids as soon as possible or to administer them at the lowest dose possible in order to achieve the desired therapeutic results.22

Based on the results of our study, and unlike the abovementioned studies, we were unable to establish a significant association between sleep quality and the intake of opioid analgesics. If it were true that morphine chloride has an impact on sleep phases, our patients should have slept worse with higher doses of the drug. In order to reach accurate conclusions in this regard, we must consider an ideal and apparently impossible scenario in which all patients were subject to the same environmental, analgesic (dose of morphine adjusted per mg/kg) and well-being conditions, in order to subsequently measure the true effects of the opiates on patients’ sleep. In our study, this situation did not take place, as patients with different levels of pain, discomfort, etc., were enrolled in this study.

Although the only method capable of identifying different sleep phases is polysomnography (among the objective sleep assessment methods available), the technical complexity and economical cost of its application has limited its use in the ICU and, therefore, its daily application in patients is not useful. Hence, for our study we made use of the RCSQ questionnaire, which is considered to be a valid and reliable subjective type of registry,7 whose application was simple. After conducting our study, we recommend monitoring patients’ sleep with validated tools, particularly when other authors have evidenced that the perception that nurses have with regard to patients’ sleep quality is significantly greater than that of the patients themselves,14,23,24 which proves the existence of an underestimation of the patients’ sleep patterns and of the need to assess them with tools such as the RCSQ questionnaire, mentioned above. Based on the results obtained in this research study, we emphasize the importance of periodically monitoring the sleep quality of patients admitted to ICUs as a measure of care quality.

Study limitationsThe lack of uniformity due to the different levels of analgesia (postoperative morphine) reached by our patients limited our ability to establish a causal relationship between the intake of opioids and the worse quality of postsurgical sleep. The recent launch of a new ICU with a different environmental structure may impose a temporal limitation for the publishing of these results, given that, although this research improves with our general knowledge about postoperative sleep in patients who underwent heart surgery, it would be advisable to carry out a new study to reevaluate if a structural change has any type of impact on the environmental factors that influence the sleep quality of the patients admitted to it.

ConclusionsGiven the simplicity of its application and the relevance of the information obtained for our study, we recommend monitoring the sleep quality of patients admitted to ICUs through the use of the RCSQ questionnaire. The use of the RCSQ questionnaire during the first two nights of postsurgical admission to the ICU proved that the patients’ sleep quality was poor.

Although we did not find consistent differences explaining the individual variability with respect to the patients’ quality of sleep during the postoperative period, we did find that the environmental factors that most impacted the nighttime rest of our patients were discomfort, pain and environmental noise. In contrast, the factors that least impacted the patients sleep quality were ambient light, nursing care and the proximity of other patients. Although the distance of the patients’ beds from the nursing control unit did not seem to affect their global sleep quality, special interest must be given to optimize the level of analgesia and nocturnal well-being of patients located the farthest from the nursing control unit.

For future research, we recommend segregating the studied patient sample into groups of individuals with comparable levels of postoperative pain and discomfort.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no human or animal experiments were carried out for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they followed the protocols established by their work center regarding the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentAuthors declare that no patient data was included in this paper.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Navarro-García MÁ, de Carlos Alegre V, Martinez-Oroz A, Irigoyen-Aristorena MI, Elizondo-Sotro A, Indurain-Fernández S, et al. Calidad del sueño en pacientes sometidos a cirugía cardiaca durante el postoperatorio en cuidados intensivos. Enferm Intensiva. 2017;28:114–124.