A 9-day-old newborn consulted in the paediatric emergency department for fever of 38°C which had started two hours previously. He had associated irritability and rejection of support on the left side. He did not present other symptoms. Among the perinatal history, the positive culture of Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus, GBS) in his mother's urine culture stood out, with incomplete intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, with no clinical signs of neonatal infection during their stay in the maternity ward. His 6-year-old brother had normal vaccinations and no symptoms of infection.

The examination showed an erythematous and indurated area in the left malar region, which was hot and painful, and which encompassed the submandibular triangle. No entry points were observed on the surface or in the oral mucosa. Mild left ocular occlusion, with no lateralisation of the corner of the mouth (Figs. 1 and 2). The rest of the physical examination using devices and systems was normal.

Clinical courseGiven the presence of fever, the following were ordered: blood, urine and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tests. Blood culture, urine culture and CSF culture, and mumps serology were collected.

In the lab test results, the following stood out: leukocytosis (24,500μl) with neutrophilia (neutrophils 15,700μl, lymphocytes 4800μl and monocytes 3200μl) with normal red blood cells and platelets. Ionogram, kidney and liver profiles and amylase were normal. The results of the acute phase reactants were: C-reactive protein 11mg/l and procalcitonin 0.11ng/ml. The urine and CSF cytochemicals were normal.

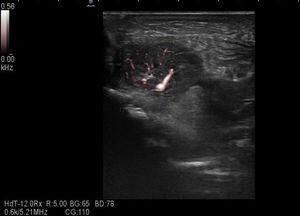

Given the physical finding, soft tissue ultrasound was requested, showing an enlarged left, hypervascularised parotid gland with intra- and extra-parotid lymph nodes, reactive in appearance, with no collections suggesting abscesses or ductal dilatations (Fig. 3).

The patient was admitted with suspected neonatal parotitis with empirical intravenous antibiotic treatment with ampicillin and cefotaxime. At 12h he started to have secretion through the Stensen duct; a sample of the exudate was collected and the antibiotic therapy was replaced by cloxacillin and cefotaxime.

Both in the culture of this exudate, and in the blood culture, the following were identified: methicillin-sensible Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus salivarius so treatment with intravenous cloxacillin was performed for 10 days. The urine and CSF cultures were negative. Good subsequent clinical course, he remained afebrile 48h following admission, with progressive improvement of the induration and mandibular erythema, with the purulent secretion disappearing through the Stensen duct until the 4th day of admission. The control blood culture and the IgM mumps serology were negative.

Final commentBacterial parotitis is an exceptional cause of infection in newborns and infants due to maternal antibodies that protect them during the first six months of life.1

The infection can be caused by retrograde bacterial flow through the Stensen duct, and less frequently by haematogenous seeding.2S. aureus is the most common isolated microorganism (65%). Second, and with greater association with generalised clinical symptoms and meningitis, is GBS infection. Infections by other gram-negative, anaerobic and streptococcal bacilli have also been reported.1,3,4

The diagnosis is based on clinical findings, with swelling of the parotid gland being a universal sign. Unilateral affectation is the most common. Fever is found in less than half of cases, usually associated with bacteraemia. The lab results are usually nonspecific, leukocytosis and elevated neutrophils are the most predominant findings. The serum amylase level rises on rare occasions, due to the immaturity of this activity of the salivary isoenzyme in newborns, which makes it useless to the diagnosis, as in our case.2

The positive culture of the purulent exudate of the ipsilateral Stensen duct or the aspiration of the affected gland is pathognomonic. When this is negative, the bacterial growth of the blood culture in this clinical context highly suggests the diagnosis.5

Prematurity, male sex, need for nasogastric tube and dehydration behave as risk factors.5

The prognosis is good because they usually respond well to intravenous antibiotics. Some authors consider cloxacillin as the treatment of choice given the high frequency of S. aureus as a causative agent; however, when there is the possibility of GBS infection, as in the case we present, the empirical treatment should be broad spectrum, using a third-generation cephalosporin until the results of the cultures are known.1 Complications, in addition to septicaemia and meningitis, include salivary fistulas and abscesses, facial paralysis and mediastinitis, which may require surgery.5

Please cite this article as: Salamanca Zarzuela B, Ortiz Martín N, Morales Luengo F, Diez Monge N. Tumefacción en región malar en un neonato. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2019;37:137–138.