Zika virus is mainly transmitted through the bites of infected Aedes mosquitoes, although mother-to-child and sexual transmission have also been described. The presence of Zika virus in semen after infection seems to be not uncommon, but the duration of viral persistence has not been well-determined.

MethodsMolecular, serological and cell culture methods were used for the diagnosis and follow up of a case of Zika virus infection imported from Venezuela. Serial samples of serum, urine and semen were analyzed to investigate the persistence of the Zika virus.

ResultsZika virus was detected in semen samples up to 93 days after the onset of symptoms.

ConclusionsOur results confirm the persistence of Zika virus in semen samples for long periods after infection.

El virus Zika se transmite fundamentalmente por la picadura de mosquitos Aedes infectados, aunque también es posible la transmisión de madre a hijo y la transmisión sexual. La presencia del virus Zika en semen tras la infección parece ser algo relativamente frecuente, pero la duración de la persistencia viral no es bien conocida.

MétodosMediante técnicas moleculares, serológicas y cultivo celular se diagnosticó un caso de Zika importado de Venezuela y se tomaron muestra seriadas de suero, orina y semen para investigar la persistencia del virus.

ResultadosEl virus Zika fue detectado en muestras de semen recogidas 93días después del inicio de los síntomas.

ConclusionesNuestros resultados confirman la persistencia del virus Zika en semen por períodos prolongados de tiempo después de la infección.

In January 2016 a man in his 30s, previously diagnosed with prostatitis in December 2015 and in treatment with ciprofloxacin, presented to the Tropical Medicine Department at Hospital Clinic (Barcelona) two days after his return from a 15-day holiday trip to Venezuela. During his stay he reported self-limited hematospermia and ceftibuten was added by a local urologist to his previous ciprofloxacin regime. In the trip back to Europe he started with malaise, fever (≥39°C), myalgias, arthralgias and retro-orbital pain. One day after, he developed a total itchy body macular rash, followed by conjunctivitis. He had not been vaccinated for this trip. He had received yellow fever vaccination in the past and referred dengue fever infection during his childhood. Medical examination revealed bilateral enlarged latero cervical lymph nodes, non purulent conjuntivitis and an intense itchy maculopapular rash diffused on the face, trunk, arms and legs. He had mild transaminitis (alanine aminotransferase 195UI/L, aspartate aminotransferase 79UI/L) and elevated C-reactive protein (1.69mg/dl). A complete blood count, blood levels of electrolytes, as well as coagulation and renal-function tests were normal. Chest radiograph results were unremarkable. The fever and the cutaneous rash resolved in 3 days while malaise, weakness, and myalgia lasted for 1 week after presentation.

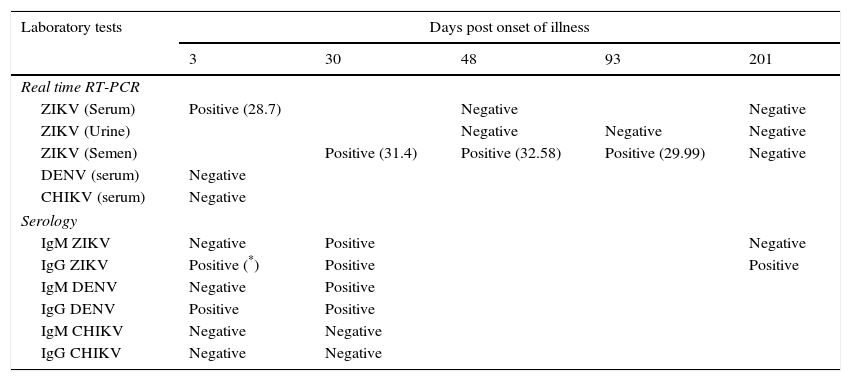

Laboratory investigationsDiagnosis of Zika virus (ZIKV) infection was established by real time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using a commercial kit (RealStar Zika Virus RT-PCR Kit 1.0, Altona Diagnostics, Hamburg, Germany) in a serum sample collected three days post onset of illness (dpi). Dengue and chikungunya RNA were not detected by specific real-time RT-PCR assays and malaria was ruled out by negative blood thick and thin smears. The presence of ZIKV was confirmed by Sanger sequencing analysis of a 270bp amplicon (from a generic flavivirus RT-PCR assay1) of the NS5 gene. The patient agreed to provide follow up samples to investigate the presence of ZIKV in semen, serum and urine samples. A summary of the samples collected and the results obtained is shown in Table 1. No ZIKV RNA was detected in follow up serum or urine samples. The first semen sample was obtained at 30dpi and tested positive by ZIKV real time RT-PCR. Two more semen samples obtained at 51 and 93dpi also contained detectable levels of ZIKV RNA. A fourth semen sample collected 201dpi tested negative for ZIKV. For cell culture, semen samples were kept frozen until inoculated onto Vero cells and monitored for virus growth by visual inspection of the cytopathic effect and by RT-PCR of culture supernatants, but the virus could not be isolated. Serological tests were performed for dengue (Panbio ELISA, Alere, Australia), chikungunya and Zika (Immunofluorescence, Euroimmun, Germany). The patient tested positive for IgG against dengue upon first presentation at the Hospital, in agreement with the dengue virus infection he reported to have suffered during his childhood. This first sample tested positive for IgG against Zika by immunofluorescence but was negative by Anti-Zika Virus ELISA (Euroimmun, Germany), in concordance with the higher specificity reported for the ELISA test.2 IgM against Zika was positive one month after onset of symptoms and was undetectable 2 months later.

Laboratory results obtained at the time of diagnosis and in follow-up samples.

| Laboratory tests | Days post onset of illness | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 30 | 48 | 93 | 201 | |

| Real time RT-PCR | |||||

| ZIKV (Serum) | Positive (28.7) | Negative | Negative | ||

| ZIKV (Urine) | Negative | Negative | Negative | ||

| ZIKV (Semen) | Positive (31.4) | Positive (32.58) | Positive (29.99) | Negative | |

| DENV (serum) | Negative | ||||

| CHIKV (serum) | Negative | ||||

| Serology | |||||

| IgM ZIKV | Negative | Positive | Negative | ||

| IgG ZIKV | Positive (*) | Positive | Positive | ||

| IgM DENV | Negative | Positive | |||

| IgG DENV | Positive | Positive | |||

| IgM CHIKV | Negative | Negative | |||

| IgG CHIKV | Negative | Negative | |||

ZIKV: zika virus; DENV: dengue virus; CHIKV: chikungunya virus.

ZIKV is, to date, the only flavivirus transmitted through sexual contact, and this mode of transmission might be more frequent than previously thought. So far, male to male,3 male to female4,5 and female to male sexual transmission6 have been documented and up to 11 countries have reported ZIKV sexual transmission. While most cases have been originated from men with previous history of ZIKV symptoms, the virus can also be spread through sexual contact before the symptoms develop and even from asymptomatic ZIKV infections.7 ZIKV sexual transmission is of public health concern, particularly for pregnant women given the possibility of ZIKV induced fetal abnormalities.8

The duration of ZIKV persistence in semen is yet poorly understood. Reports of travelers that acquired ZIKV during the present American epidemic showed viral persistence in semen for 47, 62, 76 and 80 days. Recently, a case of Zika Virus persistence for 6 months in semen has been described in a traveler returning from Haiti to Italy.9 In our case, ZIKV infection imported from Venezuela was confirmed during the viremic period 3 days after the onset of symptoms. Results of the follow up samples suggest that viral persistence was restricted to semen and longer shedding in urine was not demonstrated. Although it is possible to isolate ZIKV from semen, our attempts were not successful. Failure to isolate ZIKV from semen samples has been reported in other studies,9 with even higher viral loads (lower Ct) than in our case. The RT-PCR Cycle Threshold (Ct) values obtained in the three positive semen samples remained relatively stable until the last positive sample was tested as long as 93 days after the onset of symptoms. Our results confirm longer periods for ZIKV presence in semen and represent, to our knowledge, the first reported follow up of Zika virus in semen in Spain. Unfortunately, samples between the third and the sixth month after symptomatic illness were not available for testing. We can only suggest that somewhere between 93 and 201dpi ZIKV RNA declined to undetectable levels. Current recommendations include a precautionary period of safer sex/abstinence for 6 months after onset of illness or for 8 weeks in asymptomatic patients who traveled to areas with active ZIKV transmission.10,11 This distinction between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients has, to our knowledge, no scientific basis to support that viral persistence in semen of asymptomatic patients is shorter than in symptomatic ZIKV infections. Further studies are needed to better characterize the frequency and duration of ZIKV persistence in semen. For other emerging viruses such as Ebola, the duration of the virus in semen has been expanding as long as new studies and larger series of patients have been analyzed, moving from 91 days in the Kikwit outbreak12 to 18 months in the West African epidemic.13 Likewise, factors influencing viral persistence in semen should be identified for a better understanding of ZIKV kinetics in humans.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.