A 29-year-old woman, a professional microbiologist with no prior history of note, sought care for a fever which she had had for the past 10 days with night sweats, a feeling of pressure on the sternum, severe asthenia and persistent dry cough with no expectoration, chest pain or dyspnoea. A physical examination revealed only slight splenomegaly. Laboratory testing results were normal except for CRP and ESR, which were high. The patient reported having worked with live cultures of pathogenic microorganisms, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Francisella tularensis, though in these cases she worked in a biosafety level 3 laboratory and in a biological safety laminar flow cabinet.

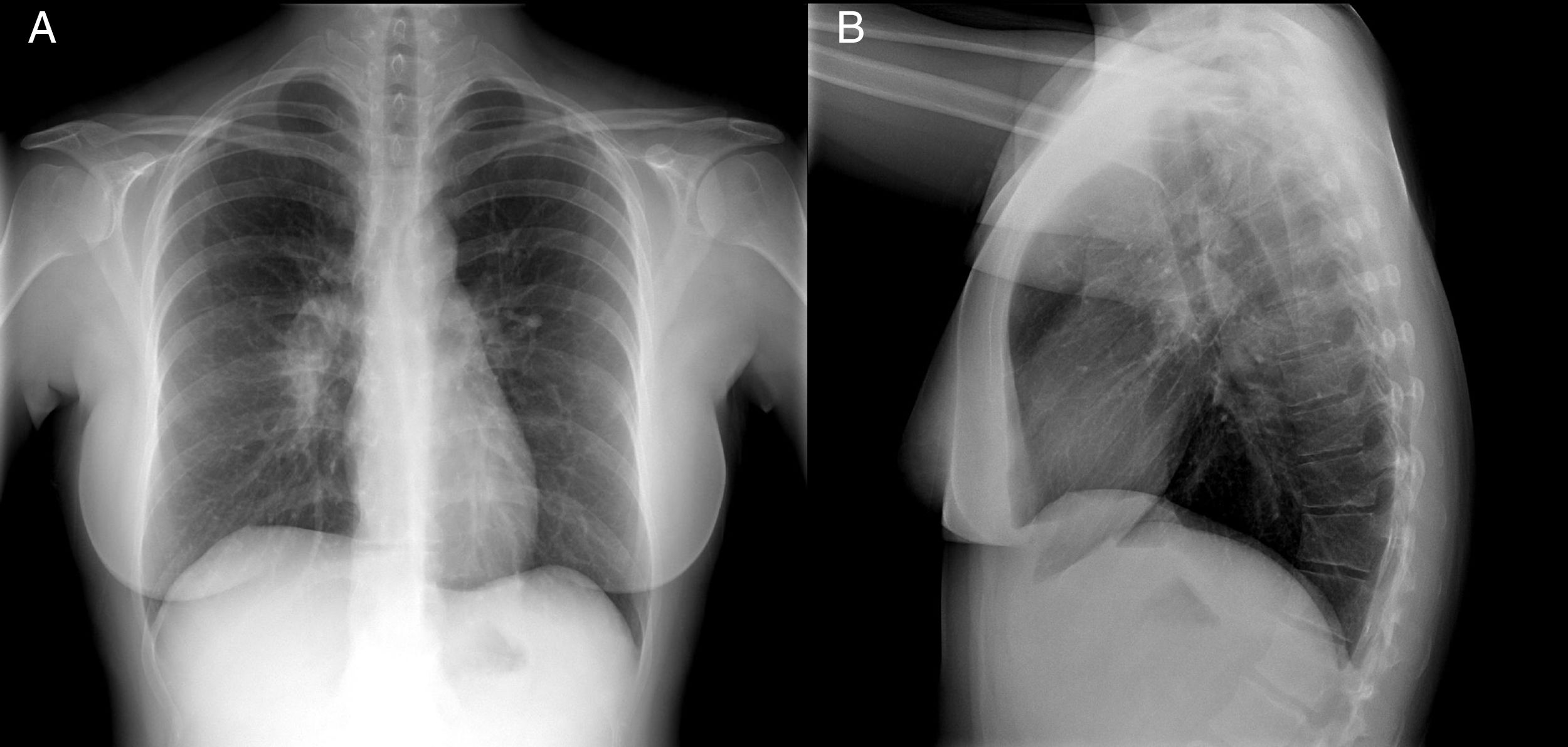

A chest X-ray showed right hilar lymphadenopathy (Fig. 1).

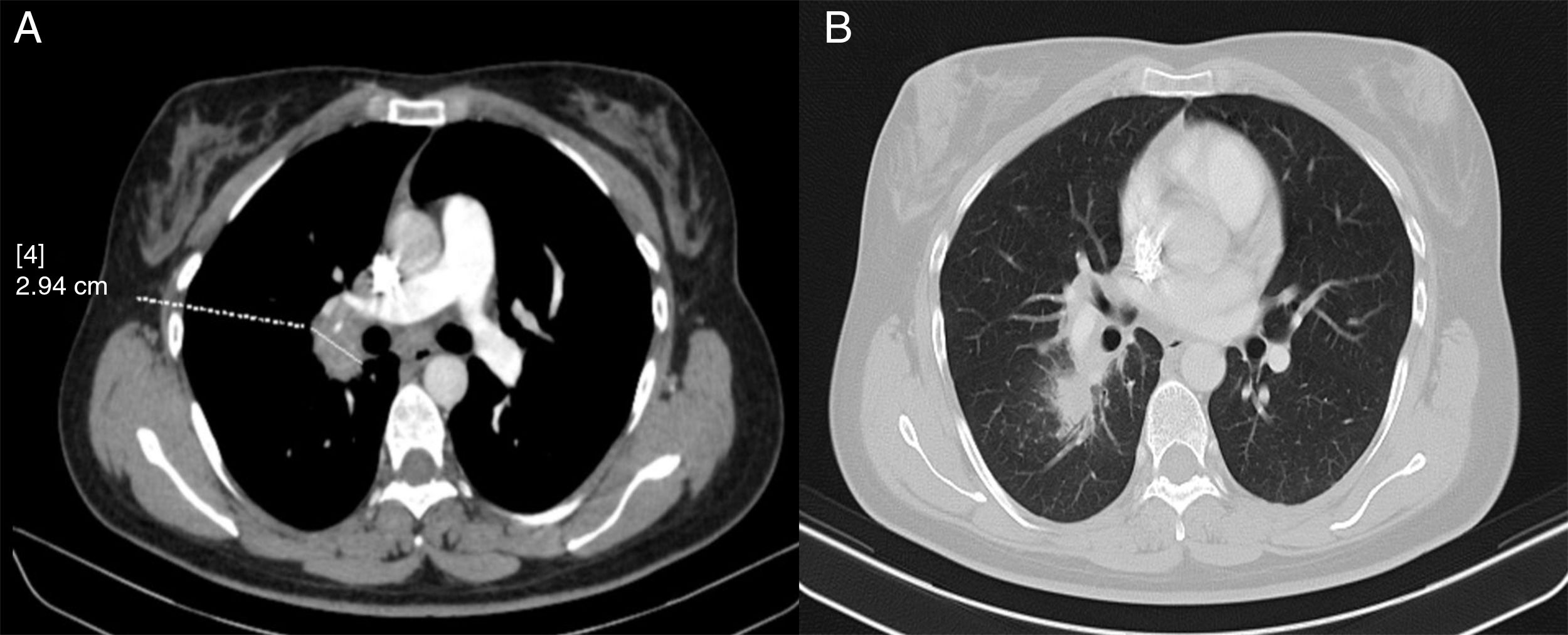

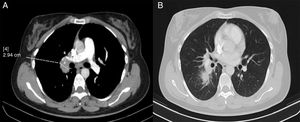

In view of these findings, a computed tomography (CT) scan was performed. This showed paratracheal, hilar, intrapulmonary and subcarinal right lymphadenopathy of a pathological size, measuring up to 2.9cm (Fig. 2).

Given the patient's occupational history and the fact that her condition was probably infectious in origin, a Mantoux test, an interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) and a QuantiFERON® test as well as serologies against Brucella, Francisella, CMV and EBV were performed as complementary tests.

Clinical courseThe tuberculin test showed no induration after 48h and the QuantiFERON® test was negative. The serologies against Brucella and CMV were negative. The serology against anti-EBNA EBV was positive; immunochromatography against F. tularensis was weakly positive and microagglutination was negative.

Given the patient's clinical condition and occupational history, the radiological and serological results obtained and the possibility of pulmonary tularaemia in its initial phase, a new serology against F. tularensis was ordered. In addition, ciprofloxacin 500mg was prescribed for 14 days. The patient's fever remitted in the first few days and all other symptoms remitted on completion of treatment. The serology performed with the second serum obtained after 15 days showed seroconversion of microagglutination with a titre of 1/160.

Final commentsTularaemia, an endemic zoonosis in the Spanish region of Castile and León, is mainly acquired following contact with multiple infected animal species, including hares, rodents and river crabs, or arthropods which act as vectors.1,2 The infectious dose of F. tularensis is the lowest of all known pathogenic bacteria (10–50 bacteria)3; therefore, contamination with contaminated dust or droplets is relatively common. This means that the infectious capacity of the microorganism represents a high risk of infection for laboratory workers, despite their adoption of safety measures required for handling this type of microorganism.4

As a result of this occupational accident, measures were taken which consisted of retraining staff who worked with highly infectious microorganisms and revising laboratory safety protocols.

F. tularensis subspecies holarctica, the subspecies involved in this case, causes less serious clinical conditions than F. tularensis subspecies tularensis.3,4 Transmission through tick bites and contact with animals usually results in glandular or ulceroglandular forms, with lymphadenopathy usually being the most significant symptom. When the route of acquisition is inhalation, it may present in the form of pneumonia, or more rarely typhoid (which may result from any form of acquisition) or follow a clinical course with fever and asthenia but no respiratory symptoms. In these cases, radiological findings are not always detected. When they do appear, they may vary and include hilar thickening indistinguishable from tuberculosis or lymphoma.4,5 In routine practice, diagnostic tests for F. tularensis are based on serology testing, since culture is difficult and dangerous to handle and PCR techniques, despite offering faster and safer detection, are not available in all laboratories.

Anti-F. tularensis antibodies may be demonstrated through tube agglutination, haemagglutination, enzyme immunoassay, immunochromatography or microagglutination. Agglutination titres are usually negative during the first phase of the disease and serology must be repeated with a new serum sample to demonstrate seroconversion. This usually appears 2 weeks after onset of symptoms and shows a peak titre after 4–5 weeks. Titres greater than or equal to 1/160 are considered positive.6 Antibodies may show cross-reaction with Brucella spp., Yersinia enterocolitica O:3 and O:9 and Proteus OX19; however, in these cases, titres against F. tularensis are almost always higher.7

Please cite this article as: López Ramos I, Galván Fernández J, Orduña Domingo A. Fiebre de origen desconocido en una trabajadora de laboratorio. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2018;36:527–528.