Early-onset neonatal sepsis (EONS) is caused by microorganisms that colonise the birth canal.1 Using prenatal antibiotics has been found to alter the vaginal microbiota2,3 and promote neonatal infections caused by Gram-negative bacilli.4,5 We present a prospective cohort study intended to determine the aetiological agents of EONS depending on the use of prenatal antibiotics and their association with resistance to first-line antimicrobial agents.

The study was conducted between January 2016 and August 2017. All newborns at Hospital Civil de Guadalajara Dr. Juan I. Menchaca in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico, were enrolled. The unit had no programme for prenatal maternal diagnosis of group B Streptococcus (GBS) infection. Prenatal antibiotics were prescribed in the obstetrics and gynaecology department in cases of urinary infection, premature membrane rupture, chorioamnionitis and maternal fever and as prophylaxis in births by Caesarian section.

EONS was diagnosed when newborns showed clinical signs of sepsis and microbial growth in cultures of blood and/or CSF before 72h of age.6 Information was gathered on administration of prenatal antibiotics by interviewing the mother and reviewing the clinical files. Administration was classified as pre-partum (in the 72h before labour) or intra-partum.

During the study, 13,899 births were recorded; 39.3% of which were by Caesarian section. This high frequency was probably due to the study hospital being a specialist facility. Newborns had a gestational age <37 weeks in 13.6% of cases, and in 3.3% of cases there were maternal risk factors for infection: unexplained fever (n=6), chorioamnionitis (n=11), urinary tract infection (n=109) and premature membrane rupture (n=333).

Prenatal antibiotics were received in 24.2% of cases (n=3370). The most commonly prescribed antimicrobial agents were cefalotin (70.4%), ampicillin (20.3%) and clindamycin (4%). Administration was more common in births by Caesarian section (53.8% vs 5.1%; p<0.001), multiple births (60.5% vs 23.1%; p<0.001), premature births (40.7% vs 21.7%; p<0.001), newborns with a weight ≤2500g (38% vs 21.6%; p<0.001) and children of mothers with risk factors for infection (59.5% vs 23%; p<0.001).

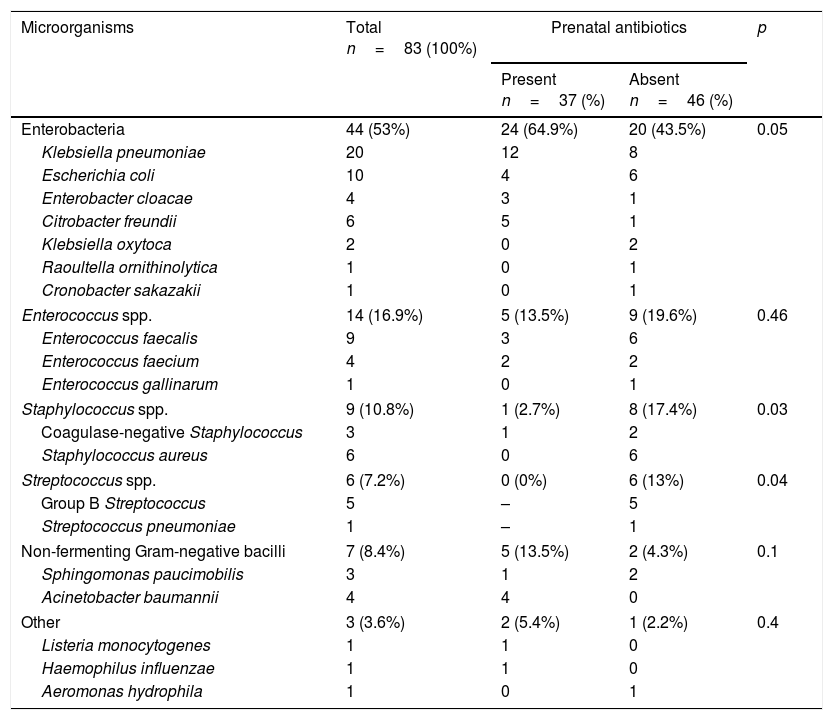

Of the 72 EONS events diagnosed (incidence 5.18 per 1000 live newborns), 11 were polymicrobial (Table 1). The most common cause of EONS was enterobacteria (53%). Overall, there was resistance to ampicillin in 88.2% of cases, to sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim in 20.5%, to ceftriaxone in 15.9%, to piperacillin-tazobactam in 15.8%, to gentamicin in 13.6%, to meropenem in 9.1% and to amikacin in 2.3%. The most commonly isolated microorganism was Klebsiella pneumoniae (24.1%). This was consistent with patterns of resistance to antimicrobial agents in recent years on our unit.7

Microorganisms isolated in patients with early-onset neonatal sepsis in patients with or without prenatal antibiotics.

| Microorganisms | Total n=83 (100%) | Prenatal antibiotics | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present n=37 (%) | Absent n=46 (%) | |||

| Enterobacteria | 44 (53%) | 24 (64.9%) | 20 (43.5%) | 0.05 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 20 | 12 | 8 | |

| Escherichia coli | 10 | 4 | 6 | |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| Citrobacter freundii | 6 | 5 | 1 | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Raoultella ornithinolytica | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Cronobacter sakazakii | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Enterococcus spp. | 14 (16.9%) | 5 (13.5%) | 9 (19.6%) | 0.46 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 9 | 3 | 6 | |

| Enterococcus faecium | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| Enterococcus gallinarum | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Staphylococcus spp. | 9 (10.8%) | 1 (2.7%) | 8 (17.4%) | 0.03 |

| Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 6 | 0 | 6 | |

| Streptococcus spp. | 6 (7.2%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (13%) | 0.04 |

| Group B Streptococcus | 5 | – | 5 | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 1 | – | 1 | |

| Non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli | 7 (8.4%) | 5 (13.5%) | 2 (4.3%) | 0.1 |

| Sphingomonas paucimobilis | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 4 | 4 | 0 | |

| Other | 3 (3.6%) | 2 (5.4%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0.4 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

Similar to that seen by Mayor-Lynn et al.,8 patients infected with Gram-negative bacilli had a lower gestational age (mean 34.3 weeks, p=0.03) and a lower birth weight (mean 2048g, p=0.03); use of intra-partum antibiotics (85.7% vs 54.5%; p<0.05) was also more common in these patients.

When the link between EONS and use of prenatal antibiotics was examined, adjusting for gestational age and weight, no significant association was found (OR 1.4; 95% CI: 0.9–2.4). However, when the relationship between intra-partum antibiotics and EONS due to Gram-negative bacilli was evaluated, it was believed to be significant (OR 4; 95% CI: 1.1–14.2) regardless of age and weight.

When antimicrobial resistance was compared depending on exposure to prenatal antibiotics, resistance rates in enterobacteria were found to be no different. Infections with Enterococcus species featured higher rates of resistance to ampicillin (40% vs 0%, p=0.07) and vancomycin (20% vs 0%; p=0.3), but the relationships were not significant. All strains of Streptococcus spp. (n=6) were isolated in patients with no prenatal antibiotics (p=0.04), all were sensitive to penicillin and, as reported by Capanna et al.,9 there was a high prevalence of resistance to clindamycin in GBS.

Similar to that reported by Stoll et al.,5 a stronger likelihood of infection with Gram-negative bacilli was seen in newborns exposed to antibiotics during labour. Schrag et al.10 found a stable frequency of EONS due to E. coli in premature births with exposure to prenatal antibiotics.

In regions where the primary aetiology of EONS is GBS, prenatal antibiotics have been shown to have a protective effect.4 However, in places were the primary cause is enterobacteria, this effect is uncertain.

Please cite this article as: Lona-Reyes JC, Pérez-Ramírez RO, Benítez-Vázquez EA, Rodríguez-Patiño V, González-Sánchez AR, Montero de Anda AK, et al. Asociación de antibióticos prenatales y etiología de la sepsis neonatal temprana en una unidad de cuidados neonatales. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2018;36:460–461.