The availability of new imaging techniques has conditioned an increase in the incidental diagnosis of small nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNET-NF). The best treatment is controversial, some authors advise a conservative approach in selected cases. Our aim is to analyze the evolution of incidental, small size PNET-NF, treated with clinical follow-up without surgery.

MethodsWe performed a retrospective analysis of a prospective database of patients diagnosed incidentally with PNET-NF since November 2007 to September 2015. We include those with PNET-NF ≤2cm and asymptomatic. The diagnosis was performed using imaging tests indicating endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in case of doubts in the diagnosis. The follow-up was performed at our center, registering clinical and/or radiological changes.

ResultsWe included 24 patients with a median age of 70 years, and a similar distribution in terms of sex. The diagnosis was made through computed tomography multidetector or magnetic resonance imaging and octreotide scan. The tumors were located mainly in the head and neck (46%), with a mean size of 11.5±3.55mm at diagnosis (5–19mm). In 2 cases endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspiration was used (8%), confirming the diagnosis of low-grade PNET with Ki67 <5%. The median follow-up was 39 months (7–100). In 19 patients (79%) they remained the same size, 21% (5) increased its size with a mean of 2.6±2mm (1–6). No cases had progression of disease.

ConclusionIn selected patients, non-surgical management of PNET-NF is an option to consider, when they are asymptomatic and ≤2cm. Larger studies with more patients and more time of follow-up are needed to validate this non-operative approach.

La disponibilidad de nuevas técnicas de imagen ha condicionado un incremento en el diagnóstico incidental de pequeños tumores neuroendocrinos pancreáticos no funcionantes (TNP-NF). El mejor tratamiento de estos tumores es controvertido: algunos autores aconsejan una actitud conservadora en casos seleccionados. Nuestro objetivo es analizar la evolución de TNP-NF incidentales de pequeño tamaño, tratados con seguimiento clínico sin cirugía.

MétodosSe realizó un análisis retrospectivo de una base de datos prospectiva de pacientes diagnosticados incidentalmente de TNP-NF desde noviembre de 2007 hasta septiembre de 2015. Incluimos aquellos con TNP-NF ≤2cm y asintomáticos. El diagnóstico se realizó mediante pruebas de imagen, indicando ecoendoscopia-punción en caso de dudas diagnósticas. El seguimiento se hizo en nuestro centro, con registro de cambios clínicos y radiológicos.

ResultadosIncluimos a 24 pacientes con una mediana de edad de 70 años y distribución similar en cuanto al sexo. El diagnóstico se realizó mediante tomografía computarizada multidetector, resonancia nuclear magnética y gammagrafía con octreótide. Los tumores se localizaban principalmente en cabeza y cuello (46%), con un tamaño medio de 11,5±3,55mm al diagnóstico (5–19mm). En 2 casos se asoció ecoendoscopia-punción (8%), confirmando el diagnóstico de TNP de bajo grado con Ki67 <5%. La mediana de seguimiento fue de 39 meses (7–100). El 79% (19) mantuvieron el mismo tamaño. El 21% (5) aumentó su tamaño con una media de 2,6±2mm (1–6). En ningún caso hubo progresión de enfermedad.

ConclusiónEn pacientes seleccionados, el manejo no quirúrgico de TNP-NF, asintomáticos y ≤2cm es una opción a tener en cuenta. Son necesarios estudios con mayor número de pacientes y un seguimiento mayor para validar esta opción conservadora.

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNT) are rare tumors with an incidence of 2.62 cases per million inhabitants,1 which represents 2% of all pancreatic neoplasms.2 PNT are a heterogeneous group of neoplasms that can cause different clinical syndromes according to the type of hormone secretion (functioning), or they may not cause clinical syndromes and manifest clinically by local compression and invasion to adjacent or distant organs (non-functioning). With the widespread use of new and improved diagnostic imaging techniques, the prevalence of non-functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNT-NF) ≤2cm has increased by more than 700% in the past 20 years according to the database of the National Cancer Institute's (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER).3–5 Nearly 90% of PNT are non-functioning.2 They can manifest at any age, with an increased incidence in patients over 45 years and a peak presentation between ages 70–80, with a mild predominance of males.5 Most are sporadic or associated with hereditary syndromes.6

PNT are classified histologically according to the 2010 guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) into 3 grades: G1, G2 and G3. G1 and G2 are well differentiated neoplasms, while G3 are poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas.7

Most incidentally diagnosed PNT-NF are well differentiated and, specifically, only 6% of those ≤2cm are malignant.8 This group of patients has better long-term survival than symptomatic patients.9

The treatment of choice for PNT-NF is surgical resection; it is the only curative treatment in most cases, with a significant impact in terms of survival.10,11 A study at Massachusetts General Hospital reports that even small PNT-NF can sometimes show aggressive behavior and should be resected12; however, the natural history of incidental PNT-NF is unclear. In contrast, another study finds that there is a strict correlation between tumor size and risk of malignancy,8 and the known substantial morbidity and mortality of pancreatectomies could favor a less aggressive treatment, including clinical/radiological follow-up.13

Due to the increased frequency of incidentally found PNT <2cm, the optimal treatment in these patients is controversial. Few studies have focused on management in these cases, and there is no high level of evidence to demonstrate the positive effect of surgery on survival. Some studies propose clinical and radiological observation as an alternative in selected cases with asymptomatic small tumors, due to their low potential for malignancy and progression.8,13–16

The objective of this study is to analyze the evolution of small-sized incidentally diagnosed PNT-NF managed with clinical follow-up without surgery in terms of survival, progression or appearance of metastasis.

MethodsWe performed a retrospective analysis of a prospective database of patients diagnosed incidentally with PNT-NF from November 2007 to September 2015, in the Hepatobiliary-Pancreatic Surgery Unit at Bellvitge University Hospital. The diagnosis was made by multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Characteristically, these lesions are well circumscribed and show contrast hyperuptake in the arterial or venous phase on MDCT; on MRI, they are hypointense in T1 and hyperintense in T2 sequences with contrast uptake in the arterial or portal phases.17,18 Octreotide scan was conducted for confirmation, and endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration was reserved for cases with uncertain diagnoses.

All patients diagnosed with PNT were evaluated jointly by members of the Hepatobiliary-Pancreatic Surgery and Radiology Units. Finally, all the patients were evaluated by an endocrinologist at our hospital, ruling out functionalism after anamnesis and determination of hormone levels.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) incidental finding of PNT; (2) non-functioning tumors, meaning absence of symptoms due to hormone hypersecretion; (3) tumors <2cm at diagnosis; (4) sporadic; (5) patients who agreed to a conservative approach.

Patients with tumors that had any of the following were excluded: (1) signs of local invasion such as ductal obstruction or invasion of vascular/adjacent structures; (2) presence of distant metastasis; (3) poorly differentiated tumors in cases where endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration was performed; (4) uncertain diagnosis.

All patients were followed up with the same imaging test every 6 months for 2 years, and yearly thereafter.19,20 We recorded changes in symptoms and tumor size as well as signs of local/distant invasion in a database with Microsoft Office Access® and Microsoft Office Excel®. Follow-up data were calculated according to the date of the last imaging test or clinical assessment in the outpatient consultation. Follow-up was closed in April 2016, and a descriptive statistical analysis of the results was conducted.

ResultsIncluded in the study were a total of 24 patients who met the inclusion criteria and accepted conservative clinical/radiological follow-up after receiving information on the risks of surgical resection and malignancy.

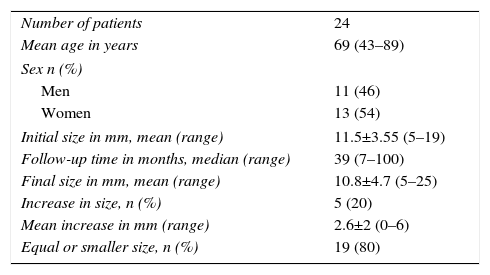

The mean age at diagnosis was 70 years (range 43–89), and 54% (13 patients) were women. Most tumors were located in the head and neck (n=11, 46%). Mean tumor size at diagnosis was 11.5±3.55mm (range: 5–19), and in the majority (87.5%) the tumor size was less than 15mm. In 3 patients (12.5%), the tumor sizes were 17, 18 and 19mm (Table 1).

Patient Characteristics.

| Number of patients | 24 |

| Mean age in years | 69 (43–89) |

| Sex n (%) | |

| Men | 11 (46) |

| Women | 13 (54) |

| Initial size in mm, mean (range) | 11.5±3.55 (5–19) |

| Follow-up time in months, median (range) | 39 (7–100) |

| Final size in mm, mean (range) | 10.8±4.7 (5–25) |

| Increase in size, n (%) | 5 (20) |

| Mean increase in mm (range) | 2.6±2 (0–6) |

| Equal or smaller size, n (%) | 19 (80) |

All tumors had been incidental findings, and the diagnosis had been confirmed by CT scan (Fig. 1), MRI or octreotide scan. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy was done in 2 patients (8%) due to the uncertain diagnosis; in both cases, the diagnosis of PNT was confirmed with a low histological grade and a Ki67 <5%.

Median follow-up was 39 months (7–100). In 5 patients (20%), the tumors increased in size, with an average increase of 2.6±2mm. Mean growth per year was estimated at 0.58mm. In the remaining 80% (19 patients), the tumors did not increase in size.

At the end of follow-up, the mean tumor size was 10.8±4.77mm (range: 5–25); the 25-mm tumor showed the largest increase (Table 1). During follow-up, no patient presented disease progression or local/distant invasion, and all remained asymptomatic. Therefore, surgical resection was not deemed necessary in any of the cases. In the case of the patient with the greatest tumor growth (from 19 to 25mm), the option of surgical treatment was dismissed due to multiple comorbidities.

DiscussionIn one of the first series on this type of tumors, Bettini et al.8 demonstrated a strict correlation between tumor size and malignancy in patients with resected PNT-NF. In a series of 177 resected patients, they found that among the 51 patients with incidentally diagnosed tumors <2cm in diameter, only 6% were malignant and none of the patients died from the disease. The authors estimated that the tumor-related risk of death is comparable to the risk of mortality from pancreatic resection. The surgical indication should be weighed against the postoperative and long-term complications of pancreatic resections. Even at Centers of Excellence, pancreatic resections are associated with high postoperative morbidity and mortality, ranging from 0% to 5%.14,16,21,22 Endocrine and exocrine insufficiency secondary to resection and other long-term complications (hepaticojejunostomy stenosis, incisional hernias, diarrhea, etc.) have an impact on the quality of life of these patients.21,22

Different studies have demonstrated that PNT are usually slow growing, which entails a better prognosis.10,23,24 Treatment with surgical resection has been the standard treatment10; however, treatment is controversial in incidentally diagnosed small-sized PNT-NF.4,8,25 Watch-and-wait management in PNT-NF has been the recommended treatment in patients with hereditary syndromes such as MEN-1, von Hippel-Lindau and neurofibromatosis. Experience has shown low rates of progression or metastasis in several series of patients with MEN-1 and pancreatic tumors <2cm in diameter and with von Hippel–Lindau syndrome and pancreatic tumors <3cm in diameter.7,26,27

Recent studies in sporadic PNT-NF also support a conservative approach in selected cases, although the size threshold to indicate resection is the subject of debate.8,16,19,28–31 Some studies have shown that, in patients with resected PNT-NF, tumor size <2cm is associated with a very low probability of lymph node metastases and G3 neuroendocrine carcinomas.8,14,24,25 In a recent series, Lee et al.14 of the Mayo Clinic retrospectively analyzed 77 patients diagnosed with PNT-NF smaller than 4cm in diameter that were sporadic, asymptomatic, and had no radiological signs of local invasion or metastasis, in whom a watch-and-wait, non-surgical management was followed. With a median tumor diameter of 1.0cm (0.3–3.2) and a mean follow-up of 45 months (3–153), the authors observed no significant change in tumor size, progression of the disease or related mortality. In another observational study on the natural history of sporadic and asymptomatic PNT-NF <2cm with a median follow-up of 34 months (24–52), Gaujoux et al.16did not observe lymphatic metastasis or distant disease in any of the 46 patients monitored. Only 6 patients (13%) showed a growth of 20% from their initial size. In the end, 8 patients (17%) were treated surgically after a median follow-up of 41 months. The resected tumors were ENETS7 grade 1, stages T1 (7 patients) and T2 (one patient), with no evidence of lymph node metastasis, vascular invasion or peripancreatic involvement in any case. The present study likewise shows that, out of the 24 patients with asymptomatic PNT-NF <2cm, none presented significant progression of the disease or tumor-related mortality during a median follow-up of 39 months.

In contrast, different studies have shown aggressive behavior and nodular metastases associated with PNT-NF <2cm in 5% of cases.3,28 Although the presence or absence of symptoms is not reported in these studies, this continues to be an important prognostic factor.4 In addition to size, tumor grade and differentiation are other variables that are associated with the biological behavior of PNT and survival. Therefore, endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy provides a cytological evaluation of the cellular differentiation and the Ki67 index of the tumor that assists in the selection of candidates.32

Our study has several limitations. The sample of 24 patients is small, and the prospective follow-up is short and conducted without a comparison group. Another of the limitations is the lack of histological confirmation, which, although not mandatory in all patients, could help select patients who would benefit from clinical follow-up without surgery. Multicenter studies with more patients and longer follow-up periods are necessary to validate this conservative option.

In conclusion, our study shows that, in select cases, the non-surgical management of asymptomatic PNT-NF <2cm is a safe option to evaluate as a therapeutic strategy. The natural history of these lesions has not been extensively studied and, if non-aggressive behavior can be demonstrated in the long term, the risk-benefit balance of non-surgical management should be considered.29 Several recently updated consensus clinical guidelines (NCCN, ENETS, Canadian National Expert Group)27,33,34 incorporate in their therapeutic algorithm the possibility of a watch-and-wait approach in asymptomatic PNT-NF <2cm. Other important factors to assess include patient age, opinion and comorbidities, as well as tumor location. Some groups recommend indicating surgical intervention during follow-up when the increase in tumor size is relevant (>20% or >5mm).16,20 Initial follow-up using imaging techniques is recommended every 6 months to assess the stability of the lesion and, once confirmed, annual follow-up scans should be conducted.35

Conflict of InterestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Uribe Galeano C, Fabregat Prous J, Busquets Barenys J, Pelaez Serra N, Secanella Medayo L, Ramos Rubio E, et al. Tumores neuroendocrinos no funcionantes de páncreas incidentales de pequeño tamaño: Resultados de una serie con manejo no quirúrgico. Cir Esp. 2017;95:83–88.

This study was presented as an oral presentation at the 10th Surgery Conference of Catalonia, held October 15 and 16, 2015 in Barcelona, Spain (reference VPV184905838128) and in poster form at the 25th Conference of the Catalonian Society of Gastroenterology, held January 28–30, 2016 in Reus, Spain.