The specialist in orthopaedic and traumatological surgery, like any other doctor, is subject to the current legal provisions while exercising their profession. Mandatory training in the medical–legal aspects of health care is essential. Claims against doctors are a reality, and orthopaedic and traumatological surgery holds first place in terms of frequency of claims according to the data from the General Council of Official Colleges of Doctors of Catalonia. Professionals must be aware of the fundamental aspects of medical professional liability, as well as specific aspects, such as defensive medicine and clinical safety. The understanding of these medical–legal aspects in the routine clinical practice can help to pave the way towards a satisfactory and safe professional career. The aim of this review is to contribute to this training, for the benefit of professionals and patients.

El especialista de cirugía ortopédica y traumatología, como cualquier facultativo, está sujeto en su ejercicio profesional a la normativa legal vigente y resulta imprescindible su formación en los aspectos médico-legales de obligado cumplimiento en la asistencia. Las reclamaciones contra los médicos son una realidad y la especialidad de cirugía ortopédica y traumatología ocupa el primer lugar en frecuencia de reclamaciones según los datos del Consejo General de Colegios de Médicos de Cataluña. Los profesionales deben conocer los aspectos fundamentales de la responsabilidad profesional médica, así como de la medicina defensiva y la seguridad clínica en su especialidad. La comprensión de estos aspectos médico-legales en la práctica clínica habitual puede ayudar a allanar el camino hacia una carrera profesional satisfactoria y segura. Con este trabajo de revisión queremos contribuir a esta formación en beneficio de profesionales y pacientes.

After the 1999 publication of “To err is human: Building a safer health system”1 by the American Institute of Medicine (USA) patient safety and the risk of claims due to malpractice have become two of the most outstanding concerns worldwide. The report alerted to adverse event rates of between 2.9% and 3.4% in hospital stay cases, of which between 53% and 58% would have been preventable. Extrapolation of results for outpatient care revealed even more alarming figures, reporting on medical care that was less safe than it should have been and arousing general interest from the public on patient safety in practical healthcare.

Clinical safetyThe importance of patient safely, defined as the absence of avoidable errors or complications resulting from the consequence of interaction between the health system and its professionals with the patient in the health care received,1 has received international recognition. In 2002 the World Health Organisation (WHO) pressed for reinforcement of the basic measures in scientific knowledge to improve patient safety and the quality of health care.2 The World Alliance for Patient Safety was founded in 2004, its purpose being to coordinate, disseminate and accelerate patient safely measures worldwide and serve as a vehicle for international collaboration between member states, the WHO, experts, consumers, professionals and the sector.2 In Spain, Act16/2003, on the cohesion and quality of the Spanish National Health service positioned patient safety at the centre of health policies.3 Patient safety, understood as the marker of health quality, seeks to reduce and prevent health service risks, thereby contributing to the excellence of the system and is reflected as such in the National Health Services Quality Management Plan.3

For two years now, scientific associations have equally intensified their actions regarding patient safety. With regards to orthopaedic and trauma surgery, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), the European Federation of National Associations of Orthopaedics and Traumatology (EFORT), the Sociedad Española de Cirugía Ortopédica y Traumatología (SEOTS) and the Sociedad Española de Cirugía de Cadera (SECCA) design jointly agreed instruments of clinical safety such as checklists,4 protocols or medical practice guidelines. The AAOS created a Patient Safety Committee which interacts with private and governmental bodies, such as the Joint Commission (TJC), WHO and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to develop programmes and materials to increase patient safety in OTS.5 EFORT is a member of Health First Europe (HFE), a non-profit making organisation which started out as a result of the non-commercial patient alliance of healthcare workers, health specialists, academics and representatives of the medical care industry. One of HFE's issues, which had already been introduced in 2004, is patient safety and infections associated with health care. Its collaboration with EFORT focused on this issue and in particular around the EU Joint Action on Patient Safety and Quality of Care (PaSQ), a 3-year project financed by the members states of the European Union (EU) which commenced in May 2013. The aim of this project was to consolidate a permanent safety network for EU patients through the Exchange of information and experiences, and the introduction of good clinical practices.6

SEOTS has contributed to the creation of protocols, clinical guidelines and informed consent documents (ICD) in this speciality, applying the principle of patient autonomy. ICDs have 3 necessary requisites: voluntariness, information and comprehension – i.e. the patient is freely allowed to accept the treatment offered once the procedure has been explained to them, with information about what could happen and awareness of possible alternatives to the proposed treatment. Their interest is reflected in the fact that, for some time, it has been the most visited section of the SEOTS website.7 Furthermore, both members and non-members download them. This serves as one example of the opportunities and functions scientific associations have as a useful instrument for patients.

Scientific associations also act more specifically in patient safety issues to adverse events of particular relevance and of a general nature. In 2010 the Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios sent out an alert regarding metal hip replacement implants,8 which became possibly one of the most reported OTS alerts in the media. It was estimated that some 93,000 people throughout the world had received an ASR® implant and had potentially suffered adverse local and systemic reactions to prosthesis wear and tear particles.9 The SECCA published a note on its website and in the journal “Revista Española de Cirugía Ortopédica y Traumatología” providing information and advice to the surgeons who had patients with this type of implant.10 Even today, there is a document on their web site with the algorithm for monitoring patients who have this metal-to-metal implant, for advising hip surgeons on the decision-making process.11

Despite that stated above, the major revolution in recent years in terms of clinical safety for the patient and in particular regarding surgical care safety, has been the WHO programme called “Safe Surgery Saves Lives”.12 This programme was created in 2007 for the purpose of improving the safety of surgical procedures throughout the world, thanks to the awareness of the following data: up to 25% of hospitalised surgical patients present with post-operative complications, the gross rate of mortality recorded after major surgery is 0.5–5%. In industrialised countries almost half of adverse events in hospitalised patients are related to surgical care, damage through surgery is considered avoidable in at least half of cases and the recognised principles of surgical safety are applied irregularly, even in the most advanced environment. International experts in clinical safety reviewed the references and experiences of clinical staff throughout the world and together stressed 4 areas in which major progress could be made: prevention of surgical wound infections, safety in anaesthesia, safety of surgical equipment and the measurement of surgical services.

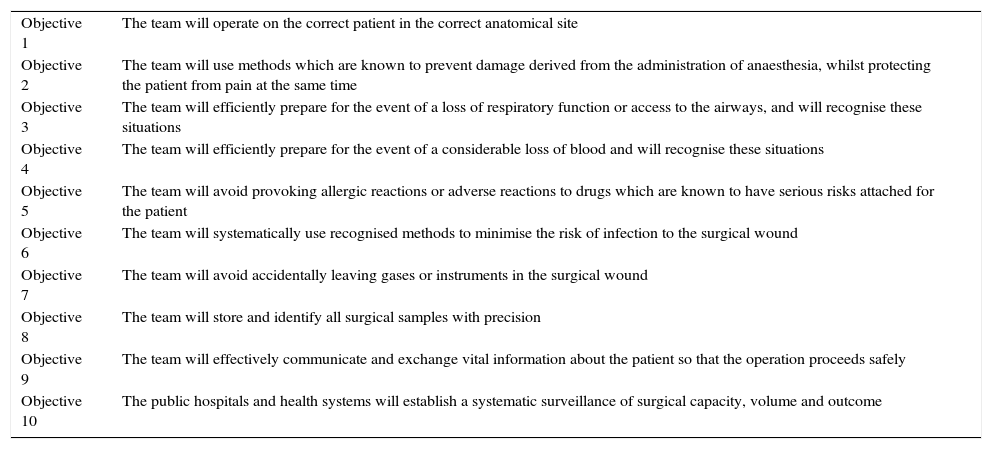

The first major measure introduced was the creation of Surgical Safety Checklist (SSC) with its 10 essential aims for surgical safety (Table 1).12 The SSC which should be completed in each surgical procedure is a simple and practical tool any surgical team in the world may use to guarantee efficient and fast observation of pre-intra-and-post-operative measures, which provide demonstrable benefits to the patient. The creation of this list, which contains 19 points applied to 3 critical moments in the surgical procedure (prior to anaesthesia, prior to cutaneous incision and prior to the patient leaving the operating theatre), entails 3 principles: simplicity, scope of application and measurability. The SSC is easy to use, useful in all environments and lends itself to measuring impact. Since its creation, it has been implemented in daily practice in over 4000 hospitals throughout the world, which have created their own SSC in keeping with their needs, but always using the same general format.

Ten essential objectives for surgical safety.

| Objective 1 | The team will operate on the correct patient in the correct anatomical site |

| Objective 2 | The team will use methods which are known to prevent damage derived from the administration of anaesthesia, whilst protecting the patient from pain at the same time |

| Objective 3 | The team will efficiently prepare for the event of a loss of respiratory function or access to the airways, and will recognise these situations |

| Objective 4 | The team will efficiently prepare for the event of a considerable loss of blood and will recognise these situations |

| Objective 5 | The team will avoid provoking allergic reactions or adverse reactions to drugs which are known to have serious risks attached for the patient |

| Objective 6 | The team will systematically use recognised methods to minimise the risk of infection to the surgical wound |

| Objective 7 | The team will avoid accidentally leaving gases or instruments in the surgical wound |

| Objective 8 | The team will store and identify all surgical samples with precision |

| Objective 9 | The team will effectively communicate and exchange vital information about the patient so that the operation proceeds safely |

| Objective 10 | The public hospitals and health systems will establish a systematic surveillance of surgical capacity, volume and outcome |

The initial outcome of its use may already be found in literature. Haynes et al.13 reached the conclusion that the use of SSC was linked to a reduction in mortality and complication rates among patients over 16 who had non cardiac surgery in any type of hospital. As an example, this study was able to demonstrate that infections of surgical wounds were reduced from 4% to 2% (P<0.001) or complications during hospital stay from 11% to 7% (P<0.001). Despite this favourable outcome, a recent study put forward serious doubts on the use and efficacy of SSC.14 In 2010, in the Canadian province of Ontario, each hospital was ordered to use the SSC. In this observational study, the hospitals were evaluated before and after SSC implementation. The main variable was surgical mortality but morbidity and readmittance rates were also analysed. Results showed that despite general adoption of SSC, there were no significant differences in mortality (0.71% vs. 0.65%; P=0.13) nor surgical complications (3.86% vs. 3.83%; P=0.29). Hospitals therefore need to customise the SSC and adapt it to the needs of their own surgical team and hospital, promoting a feeling of ownership to increase compliance and usefulness. It is unlikely that the SSC would lead to any change in clinical patient outcome without support from all members of staff. At present, the surgical community must regard the SSC as a tool for improving communication and clinical safety and be realistic with regards to its direct impact on patient safety.

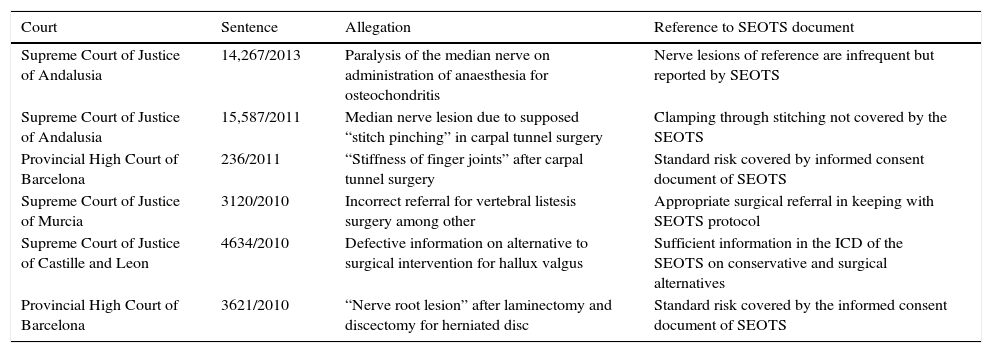

Lastly, clinical safety efforts have also been incorporated into professional medical liability insurance management through claim analysis. When faced with an adverse event in health care, doctors may be required to accept liability in the different legal spheres:15 criminal (be this serious or minor negligence according to the current Penal Code and serious or less serious according to the new Penal Code pending approval, quite aside from wilful misconduct); civil (whether contractual which is essentially in the private field, in tort, due to guilt or negligence, or of a criminal origin, derived from a crime or misdemeanour) or contentious administrative (through a claim against the Health Service or against contracted or subsidised centres). The existence of professional medical liability will be calculated in the case of damages to the patient and the concurrence of medical malpractice with proof of the causal connection between the two.16 Malpractice will be declared if medical care does not adhere to what is legally known as lex artis ad hoc in Latin and standard of care in English.16 The medical practice guidelines, protocols and DCI designed by the scientific associations are both a tool for clinical security and a potential legal guarantee that all health care and information provided will adhere to lex artis.15,16 These documents, such as the SEOTS in OTS for example, are frequently quoted in rulings on medical practice as suitable practice references (Table 2 includes examples of legislation in this regard from year 2010).

Case law reflecting informed consent documents and protocols of the Sociedad Española de Cirugía Ortopédica y Traumatología.

| Court | Sentence | Allegation | Reference to SEOTS document |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supreme Court of Justice of Andalusia | 14,267/2013 | Paralysis of the median nerve on administration of anaesthesia for osteochondritis | Nerve lesions of reference are infrequent but reported by SEOTS |

| Supreme Court of Justice of Andalusia | 15,587/2011 | Median nerve lesion due to supposed “stitch pinching” in carpal tunnel surgery | Clamping through stitching not covered by the SEOTS |

| Provincial High Court of Barcelona | 236/2011 | “Stiffness of finger joints” after carpal tunnel surgery | Standard risk covered by informed consent document of SEOTS |

| Supreme Court of Justice of Murcia | 3120/2010 | Incorrect referral for vertebral listesis surgery among other | Appropriate surgical referral in keeping with SEOTS protocol |

| Supreme Court of Justice of Castille and Leon | 4634/2010 | Defective information on alternative to surgical intervention for hallux valgus | Sufficient information in the ICD of the SEOTS on conservative and surgical alternatives |

| Provincial High Court of Barcelona | 3621/2010 | “Nerve root lesion” after laminectomy and discectomy for herniated disc | Standard risk covered by the informed consent document of SEOTS |

The National Health Service (NHS) has estimated that there are 850,000 medical errors in the United Kingdom derived from approximately 6000 claims per year to the National Health Service Litigation Authority (NHSLA).17 Greenberg et al.18 reported that 3.7 out of every 10 adverse events leads to a claim and they show that attempts at clinical safety would potentially lower them. Furthermore, in Spain it has been reported that in only 17.2% of claims is there a compensable medical error. Although not all adverse events are followed up by a claim, nor are all claims based on a genuine medical error, their analysis has shown that it is a useful clinical tool which may identify both medical care errors as points on which to develop improvements to avoid negative outcomes. Patient safety measures taken in the area of medical professional liability (MPL) insurance which deals with claims for supposed malpractice, incorporates the analysis of claims in insurance management and develops recommendations that help to increase clinical safety of patients and legal protection for professionals.19,20

Claims from medical liabilityRegardless of the above-mentioned efforts made during the last few decades regarding patient safety issues, there has been an internationally recorded increase in claims relating to MPL. Countries like USA are immersed in the malpractice crisis with continued legislative reforms in this area.15,16,21 These reforms, among others, have established limits to compensatory amounts and proper restrictions to bringing cases to court: it has been proven that compensatory amounts have been reduced but there has been little and controversial description of the possible multiple and varied consequences, with limited effect on the existing crisis.21 The health care context of the USA is, however, clearly different from the Spanish one, with its different doctor/patient relationship in its predominantly private network and, its MPL policy premiums and much higher doctors’ fees: several comparisons have been published underlining the differences and similarities in this respect.22–24 The number of claims in Spain appears to have stabilised in the last few years and the compensatory amounts are very much lower than those of USA.22 Published data, however, remains scarce.19

In Spain, approximately 1.33% of medical professionals insured under the policy of the Consejo General de Colegios de Médicos de Cataluña (CGCMC) annually receive some sort of claim, although only 0.26% terminate in professional liability (whether this be through legal judgement or out of court settlement).23 Surgery has been identified as an area of medicine with particularly high rates of adverse events and claims. According to CGCMC data, 69.03% of claims made between 1986 and 2012 relate to surgical procedures and those specialties with particularly high damage rates are surgical or medical-surgical.25 The most outstanding are OTS specialties, together with obstetrics and gynaecology or psychiatry which is beginning to be the subject of claim studies in Spain.,26 although this is a clearly infra-researched area.27–32 Studies in Spain itself are particularly necessary in this area, since health and legal systems may be so different country to country that the international results are inapplicable to those of Spain.23

Orthopaedic and trauma surgery: a high risk specialtyAt present, it is essential for orthopaedic and trauma surgeons to be aware of the relevant legal–medical governing health care. In Spain, the few studies which have been published on MPL33 and clinical safety34 in OTS have attempted to establish a reference framework to lend a certain peace of mind for the exercise of professional functions.33 Beyond our borders, Matsen et al.35 underline the need for OTS specialists to become aware of data on claims against specialties and points out that the dissemination of events could improve the quality of patient care. In this regard, Ohrn et al.36 conclude that the study by specialists of claims obtained in independent systems, such as the County Councils’ Mutual Insurance Company, is a very powerful method for the identification of adverse events occurring in the speciality.

General analysis of specialities in the CGCMC positions OTS first in frequency of claim and it accounts for 17.3% of surgical procedures with claims against them: it must be considered a speciality with a high risk of claims.23,25 This is repeated in countries such as England,37 Sweden,36 Italy38 or USA.35 The County Councils’ Mutual Insurance Company which is responsible for claims from Norway, Denmark, Finland and Sweden36 receives 9000 claims per year, of which half receive financial compensation and OTS is the specialty with the highest rate of claims (28%), followed by general surgery (20%), obstetrics and gynaecology (11%), anaesthesiology (6%) and internal medicine (5%). In Rome,38 out of 1925 claims received between 2004 and 2010, 243 (13%) were related to OTS (61% of these claims were secondary to elective surgery and 39% to non elective surgery—traumatology).38

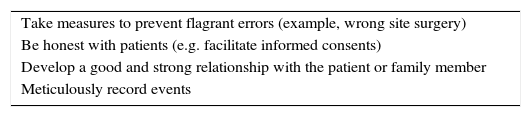

In England between 1995 and 2012 the NHSLA identified a total of 10,273 OTS claims.37 On classifying them by anatomical area it was observed that there are some areas with more claims than others: hip and knee (25.8%), hand and wrist (13.2%), foot and ankle (12.6%), back (9.9%), leg (9.6%), shoulder and elbow (7.9%), arm (1.4%) and non specified area (19.7%). Studies focused on specific locations39 or specific procedures40,41 provide information of particular interest for sub-specialists. In a recent American study on medical malpractice in hand surgery,39 it may be observed that the 2 conditions with the most claims are the treatment of carpal tunnel and wrist fractures, 2 types of highly prevalent conditions. In this same report39 recommendations for prevention are given to hand surgeons to avoid malpractice claims (Table 3). In United Kingdom, Atrey et al.42 found that of the 69 claims regarding the hand and the wrist, 39 were due to lesions of the median nerve during its release. In a specific study40 of 70 claims of distal radius fractures, the most frequent causes for claims were non-union of fractures, deformity and loss of movement. Apart from these complications resulting from an inappropriate follow-up of the patient, the poor relationship between doctor and patient was also cited as the cause for claiming in 51 of the 70 cases. Furthermore, the analysis of 167 claims in England41 after a total hip replacement detected that the most frequent claims were regarding leg-length differences, periprosthetic fracture and poor positioning of the acetabular component, particularly in cemented prostheses.

Preventative measures to avoid claims against medical malpractice.

| Take measures to prevent flagrant errors (example, wrong site surgery) |

| Be honest with patients (e.g. facilitate informed consents) |

| Develop a good and strong relationship with the patient or family member |

| Meticulously record events |

Matsen et al.35 unveiled 464 OTS claims between 2008 and 2010 in California, which were classified according to the type of event. In this case, the most frequent cause were errors in protecting structures during surgery (15%), errors in fracture treatment (14%) and errors of prevention, diagnosis or treatment of infection (11%).

However, the most frequent causes for claims against the NHSLA, between 2000 and 2006, was the presence of a post-operative infection.42 In Sweden,36 the most frequent claims were also due to infections acquired in hospital and cases of sepsis (specifically to infections after an initial prosthesis of the knee or hip, which are common and frequent procedures in Spain). In 2013 in Catalonia alone, according to the programme of Vigilancia de las Infecciones Nosocomiales en los Hospitales de Cataluña (VINCat), 255 initial knee and hip prosthesis resulted in infection.43

Articles which use this type of event may be of interest to OTS surgeons and to service management, hospital managers or planners. In USA Medicare created a ranking of hospital according to claims made due to infection after hip prosthesis and detected which hospital had higher than expected infection rates, thereby introducing strategies to reduce that rate of infection as a result.44

Special claims: “surgery in the wrong place” and defective informationThere are 2 types of potentially avoidable OTS claims, which do not depend on surgical activity itself and on adverse effects and if they occur, the risk of claim and financial compensation for the patient is obviously very high. These 2 types of claims are “wrong site surgery” and non-compliance or non usage of the informed consent form.45–47

In the AAOS bulletin it states that “successful legal defence for ‘wrong site surgery’ is almost impossible”. The correct interpretation of wrong site surgery is not “surgery on the wrong side”,48 because the concept covers both surgery performed on the wrong side and that performed at the wrong site (for example, an ankle instead of a foot, although it is on the same side of the body), on the wrong patient and the performing of a procedure which is different to that planned and for which the patient gave their consent (e.g. knee prosthesis instead of an arthroscopy).45,48 In one study made by the NHSLA in England and Wales,45 of claims for “wrong site surgery” between 1995 and 2007, the specialty with the most claims was OTS (29.8%), followed by deontology (16.8%), general surgery (13.7%) and obstetrics and gynaecology (9.2%). Between 2006 and 2007, in England and Wales, out of a total of 845,692 OTS procedures, there were 8 claims for this cause, with a rate of around one claim for every 100,000 procedures performed.45

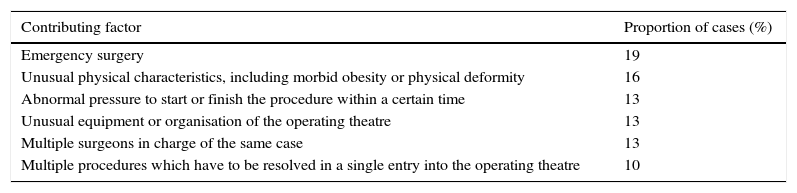

Different studies have examined which factors lead to wrong site surgery and the TJC has identified a series of factors contributing to the increase in the risk of this49 (Table 4). Essentially, many aspects are involved and the majority involve a breakdown in communication between the members of the surgical team and the patient and the family. Other causes contributing to this event are problems with the established protocols (such as that marking an unrequired surgical site), absence of verification in the operating theatre, and verification using the checklists, incomplete pre-operative assessment, problems with staff, distracting factors in the operating theatre, incomplete availability of patient information in the operating theatre and hospital organisational patterns. In one study50 on foot surgery in Spain a protocol was established to mark the side to be operated on with the participation of the whole team involved in the surgical process and the patient or family member as well, as it concluded that there were several different points of risk which could lead to this surgical error being committed, among which the following were outstanding: lack of noting which side was to be operated on was more frequent in OTS clinical history than in anaesthesiological clinical history, there were incongruences of the side noted in the documents on the clinical background and this was most frequent in patients with previous surgery performed on a foot.50 Thus, as with any event in wrong site surgery, it is ultimately unacceptable if the surgeon in charge does not ensure that all the appropriate precautions have been taken to reduce the risk of this type of occurrence to a minimum.45

Information regarding the Joint Commission on factors which increase the risk of “wrong site surgery”.

| Contributing factor | Proportion of cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Emergency surgery | 19 |

| Unusual physical characteristics, including morbid obesity or physical deformity | 16 |

| Abnormal pressure to start or finish the procedure within a certain time | 13 |

| Unusual equipment or organisation of the operating theatre | 13 |

| Multiple surgeons in charge of the same case | 13 |

| Multiple procedures which have to be resolved in a single entry into the operating theatre | 10 |

With regards to insufficient compliance or absence of the ICD, we must view claims in this respect within the context exercising medicine which is essentially influenced by major sociocultural changes.15,16 The enactment of Law 41/2002, the basic regulator of patient autonomy and of the rights and publications regarding clinical information and documentation, did away with the paternalistic physician–patient relationship and developed the predominance of information and autonomy. Legislation, both autonomous and state, obliges the physician to inform the patient of the benefits, risks and alternatives of proposed surgery.51 Article 8.2 establishes that consent will generally be verbal but will be written in the case of “surgical intervention, diagnostic procedures and invasive therapies, and in general application of procedures which will lead to notable risk or inconveniences and foreseeable negative repercussions for the patient's health”.52 Professionals must appropriately communicate the current complexity of treatment to those patients they are treating, presenting any possible adverse effects of the increasingly sophisticated techniques to combat high expectations, in compliance with prevailing legislation regarding patient autonomy and respect of patient rights. As a result the risks governing professional liability are lowered.15,16 We must not forget that correct compliance of medical and legal precepts in clinical practice is obligatory for medical practice to be considered in keeping with la lex artis.

These supposed MPL from defective information where it is not proven that the physician had informed the patient of the ensuing complication, are particularly significant in elective and scheduled surgery. The ICD is the essential proof that this information procedure was carried out with the patient and its absence, when obligatory, is a compensable civil wrong from defective information. The physician failed in his duty to inform the patient (informed consent). This lack of information leads to the situation of a patient who undergoes surgery without being correctly informed of possible risks. If a complication unfortunately arises the patient has not had the opportunity previously to avoid it by refusing to undergo surgery. Legal compensation is derived from the patient's missed opportunity to refuse surgery and thus avoid the subsequent complication.51

On the contrary, several rulings may be observed from those listed in Table 2 where the physician is exonerated from any guilt from the constancy of documented information on the ICD regarding the ensuing complication as a typical risk. Furthermore, in a Swedish study36 with 6029 OTS claims, 3336 (55%) were assessed as an adverse event and consequently were compensated for financially, whilst the remaining 2668 (45%) did not receive financial compensation. The most common cause for rejecting the claim was that the lesion assessed was an “inevitable consequence” of the appropriately described treatment (27%) or that the “lesion was not treatment related” (24%).

Defensive medicine in trauma and orthopaedic surgeryThere has been an international alert on the increase in defensive medicine from the increase in claims for presumed MPL, and also in the OTS specialty.15,16,21,53,54 Defensive medicine include medical practices which exonerate physicians from MPL with no clinical benefit for patients.53 The damage involved for the patients is undeniable and has even been described as reaching limitations in healthcare access in certain areas of medicine.21 The most prevalent practices of defensive medicine are the referral for unnecessary tests, avoiding high risk procedures, not treating complex patients and referring patients to other specialists.53

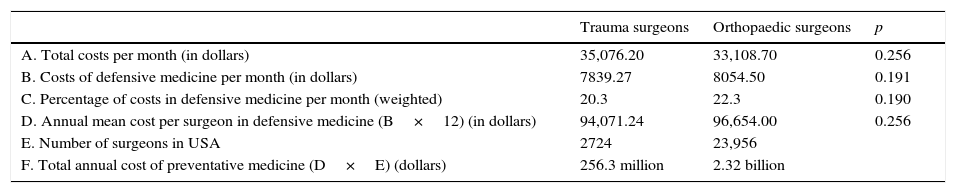

Sathiyakumar et al.53 reported that, although in 2012 data on defensive medical practice existed in OTS, no study would have specifically researched its prevalence among orthopaedic surgeons. The authors53 found that, despite studies existing to affirm that the trauma surgeons were subject potentially to a higher risk of legal procedures due to malpractice than orthopaedic surgeons, findings revealed that trauma surgeons did not practice more defensive medicine than orthopaedic surgeons in terms of the extra number of image tests requested, laboratory tests, biopsies, referrals to specialists or hospital admission. Furthermore, in this report53 the monthly and annual costs of trauma and orthopaedic surgeons on defensive medicine were also calculated separately in USA (Table 5). One recent study54 which made a forward-looking analysis of defensive medicine in the imaging tests requested by orthopaedic and trauma surgeons in Pennsylvania, concluded 2 major facts: the proportion of defensive imaging tests ordered by a specialist who had been accused of medical malpractice during the 5 years prior to the study was significantly higher than the proposition of defensive imaging tests ordered by specialists who had not been accused during the same period of time (24.6% compared with 15.1%; P<0.001), and that the proportion of defensive imaging tests requested by a specialist with over 15 years experience was considerably higher than the proportion of those ordered by those with less experience (20.8% compared with 17.1%%; P=0.03). It would therefore appear that the specialists who were accused and those with the most experience tend to use defensive medicine to a much greater extent. For this reason, Meinberg et al.,55 in their study named Medicolegal information for the young traumatologist: Better safe than sorry, concludes that the comprehension of the different aspects of the medical and legal problems in clinical practice may prevent a significant amount of fear and incomprehension of a young trauma surgeon and help to smooth the path to a satisfactory professional career.

Monthly and annual costs of defensive medicine of the trauma surgeons and orthopaedic surgeons in United States.

| Trauma surgeons | Orthopaedic surgeons | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Total costs per month (in dollars) | 35,076.20 | 33,108.70 | 0.256 |

| B. Costs of defensive medicine per month (in dollars) | 7839.27 | 8054.50 | 0.191 |

| C. Percentage of costs in defensive medicine per month (weighted) | 20.3 | 22.3 | 0.190 |

| D. Annual mean cost per surgeon in defensive medicine (B×12) (in dollars) | 94,071.24 | 96,654.00 | 0.256 |

| E. Number of surgeons in USA | 2724 | 23,956 | |

| F. Total annual cost of preventative medicine (D×E) (dollars) | 256.3 million | 2.32 billion |

The OTS specialist, like any other specialist, must comply with the prevailing legislation in the exercise of his or her profession and training is essential in legal–medical aspects of obligatory fulfilment in healthcare. Claims made against doctors are a reality and on the majority of occasions they are a consequence of a poor outcome or an unexpected or unavoidable complication in a disease, diagnostic procedure used or treatment, rather than medical negligence. The exercise of medicine has an effect on the most valuable human assets: health and life. It is therefore understandable that patients and family members make claims to the courts or outside of them when events which negatively affect health occur and the responsibility for which they rightly, or wrongly, attach to the doctor. We consider it essential to analyse the causes of claims according to specialty and analyse which the procedures with the most claims are made against them. Reports of this nature may promote training and be beneficial to both professionals and patients.

Level of evidenceLevel V.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FinancingThis study received support from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI 10/00598).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare they have no conflicts of interest relating to this article.

Please cite this article as: Bori G, Gómez-Durán EL, Combalia A, Trilla A, Prat A, Bruguera M, et al. Seguridad clínica y reclamaciones por responsabilidad profesional en Cirugía Ortopédica y Traumatología. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2016;60:89–98.