Intestinal obstruction development after upper and lower abdominal surgery is part of the daily life of every surgeon. Despite this one, there are very few good quality studies that enable the frequency of intestinal obstruction to be assessed, even though postoperative adhesions are the cause of considerable direct and indirect morbidity and its prevention can be considered a public health problem. And yet, in Mexico, at this time, there is no validated recommendation on the prevention of adhesions, or more particularly, in connection with the use of a variety of anti-adhesion commercial products which have been marketed for at least a decade.

Intraperitoneal adhesions develop between surfaces without peritoneum of the abdominal organs, mesentery, and abdominal wall. The most common site of adhesions is between the greater omentum and anterior abdominal wall. Despite the frequency of adhesions and their direct and indirect consequences, there is only one published recommendation (from gynaecological literature), regarding peritoneal adhesion prevention.

As concerning colorectal surgery, more than 250,000 colorectal resections are performed annually in the United States, and 24% to 35% of them will develop a complication. The clinical and financial burden of these complications is enormous, and colorectal surgery has been specifically highlighted as a potential prevention point of surgical morbidity.

El desarrollo de oclusión intestinal después de la cirugía abdominal superior e inferior es parte de la vida cotidiana de cada cirujano. Existen pocos estudios de calidad que permiten una apreciación de la frecuencia de la oclusión intestinal postoperatoria. Las adherencias postoperatorias son causa de una considerable morbilidad y su prevención se puede considerar un problema de salud pública. En México, no hay ninguna recomendación validada (que en relación al trato gentil a los tejidos, por lo obvio no se menciona) sobre la prevención de las adherencias ni, más en particular, en relación con el uso de una variedad de productos comerciales antiadhesión que han sido comercializados durante al menos una década.

Las adherencias intraperitoneales se desarrollan entre las superficies sin peritoneo de los órganos abdominales, mesenterios, y la pared abdominal; el sitio más común de formación de adherencias es entre el epiplón mayor, y la pared abdominal anterior. A pesar de la frecuencia de adherencias y sus consecuencias directas e indirectas, solo hay una recomendación publicada (a partir de la literatura ginecológica), en relación con la prevención de adherencias peritoneales. Respecto a la cirugía colorrectal se realizan más de 250,000 resecciones colorrectales anualmente en los Estados Unidos, y del 24 a 35% de ellos desarrollarán una complicación. La carga clínica y económica de estas complicaciones es enorme, y las cirugías colorrectales se han puesto de relieve específicamente como un punto de morbilidad quirúrgica potencialmente prevenibles.

Adherences account for 75% of the intestinal obstruction causes, as well as chronic pelvic pain and infertility in women with previous abdominal surgery. According to estimates, in the United States every year more than 300,000 patients are operated on to treat obstruction of the small intestine, induced by adherences. This produces work incapacity and an increase in the number of hospitalisations derived from this problem, in patients receiving medical treatment as a first measure.

Several agents have been used to prevent adherences, including anti-inflammatory agents, antibiotics, biochemical agents and physical barriers; unfortunately, none of these have been efficient in the prevention of postoperative adherences.

Intra-peritoneal adherences are defined as any congenital or post-traumatic scars occurring between two adjacent peritoneal surfaces that are normally separated. After surgical interventions that cause a peritoneal trauma, tissue from the abnormal scar can develop between the normally free peritoneal surfaces, leading to the formation of definite adherences.1

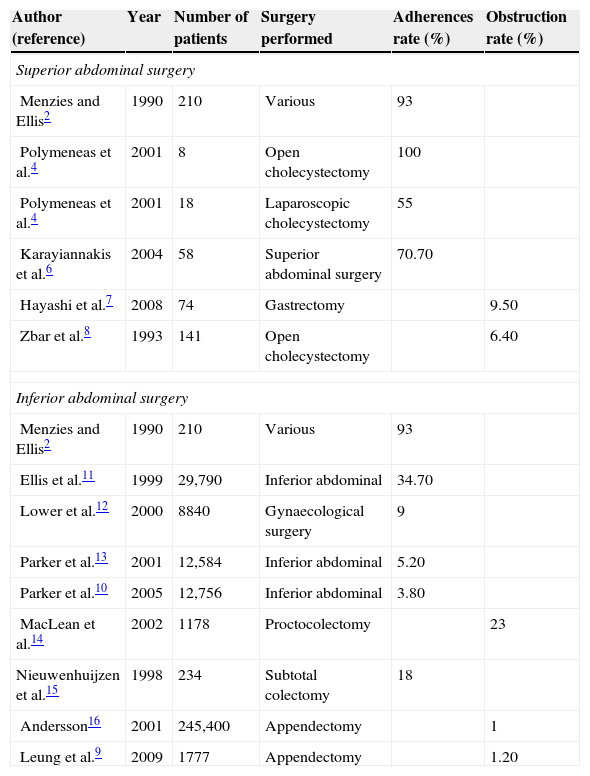

Incidence of postoperative adherencesThe frequency of adherences formation after the peritoneal abdominal surgery is difficult to assess, due to the lack of high-level evidence studies in this area.

Frequency of postoperative adherences after superior abdominal surgeryBased on the available data, peritoneal adherences develop in 93–100% of the cases after a laparotomy for superior abdominal surgery in adults.2,3 The laparoscopic approach seems to diminish risk in 45%.4 The frequency of surgical re-intervention for symptoms related to adhesion varies based on the initial procedure time, but in all cases remains below 10% in adult patients between 6.4 and 10%.5–8

The greater omentum is the most commonly involved organ in the formation of adherences.2

Frequency of postoperative adherences after inferior abdominal surgeryAfter the open inferior abdominal surgery, 67–93% of the patients developed adherences,9 but only 5–18% of these cases were symptomatic (intestinal obstruction). The complication rate varies based on the type of surgery and the duration of postoperative follow-up.

The complication rate is directly related to the adherences, leading to one or more hospitalisations, and the average is 3.8% (Table 1).2,4,6–16

Incidence of adhesions and abdominal obstruction after abdominal surgery.

| Author (reference) | Year | Number of patients | Surgery performed | Adherences rate (%) | Obstruction rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superior abdominal surgery | |||||

| Menzies and Ellis2 | 1990 | 210 | Various | 93 | |

| Polymeneas et al.4 | 2001 | 8 | Open cholecystectomy | 100 | |

| Polymeneas et al.4 | 2001 | 18 | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 55 | |

| Karayiannakis et al.6 | 2004 | 58 | Superior abdominal surgery | 70.70 | |

| Hayashi et al.7 | 2008 | 74 | Gastrectomy | 9.50 | |

| Zbar et al.8 | 1993 | 141 | Open cholecystectomy | 6.40 | |

| Inferior abdominal surgery | |||||

| Menzies and Ellis2 | 1990 | 210 | Various | 93 | |

| Ellis et al.11 | 1999 | 29,790 | Inferior abdominal | 34.70 | |

| Lower et al.12 | 2000 | 8840 | Gynaecological surgery | 9 | |

| Parker et al.13 | 2001 | 12,584 | Inferior abdominal | 5.20 | |

| Parker et al.10 | 2005 | 12,756 | Inferior abdominal | 3.80 | |

| MacLean et al.14 | 2002 | 1178 | Proctocolectomy | 23 | |

| Nieuwenhuijzen et al.15 | 1998 | 234 | Subtotal colectomy | 18 | |

| Andersson16 | 2001 | 245,400 | Appendectomy | 1 | |

| Leung et al.9 | 2009 | 1777 | Appendectomy | 1.20 | |

The most common site for adherence development is between the greater omentum and the closure of the mid-line, but these adherence points rarely cause intestinal obstruction.1 Risk factors for adherence development include the number of interventions, history of peritonitis and age lower than 60 years old.15

Regarding laparoscopic surgery, there is no high-level evidence available in this context. The frequency of adherences requiring re-intervention after the inferior abdominal laparoscopic surgery has been assessed in 2% of the patients after benign colorectal surgery, in 2.8% of the patients after rectal surgery with a malign process, and in 0.76% of the patients after an appendectomy.17–21 Long-term incidence of adhesion related to postoperative obstruction has been measured in two prospective, randomised studies to compare laparoscopy vs. laparotomy for colorectal surgery. These studies showed a statistically significant difference in the postoperative obstruction rate: 5.1 vs. 6.5% in Schölin et al.’s21 study, 2.5 vs. 3.1% in Taylor et al.’s study.22 The highest postoperative obstruction rate was observed in the group of patients that required conversion from laparoscopy to laparotomy (6%).

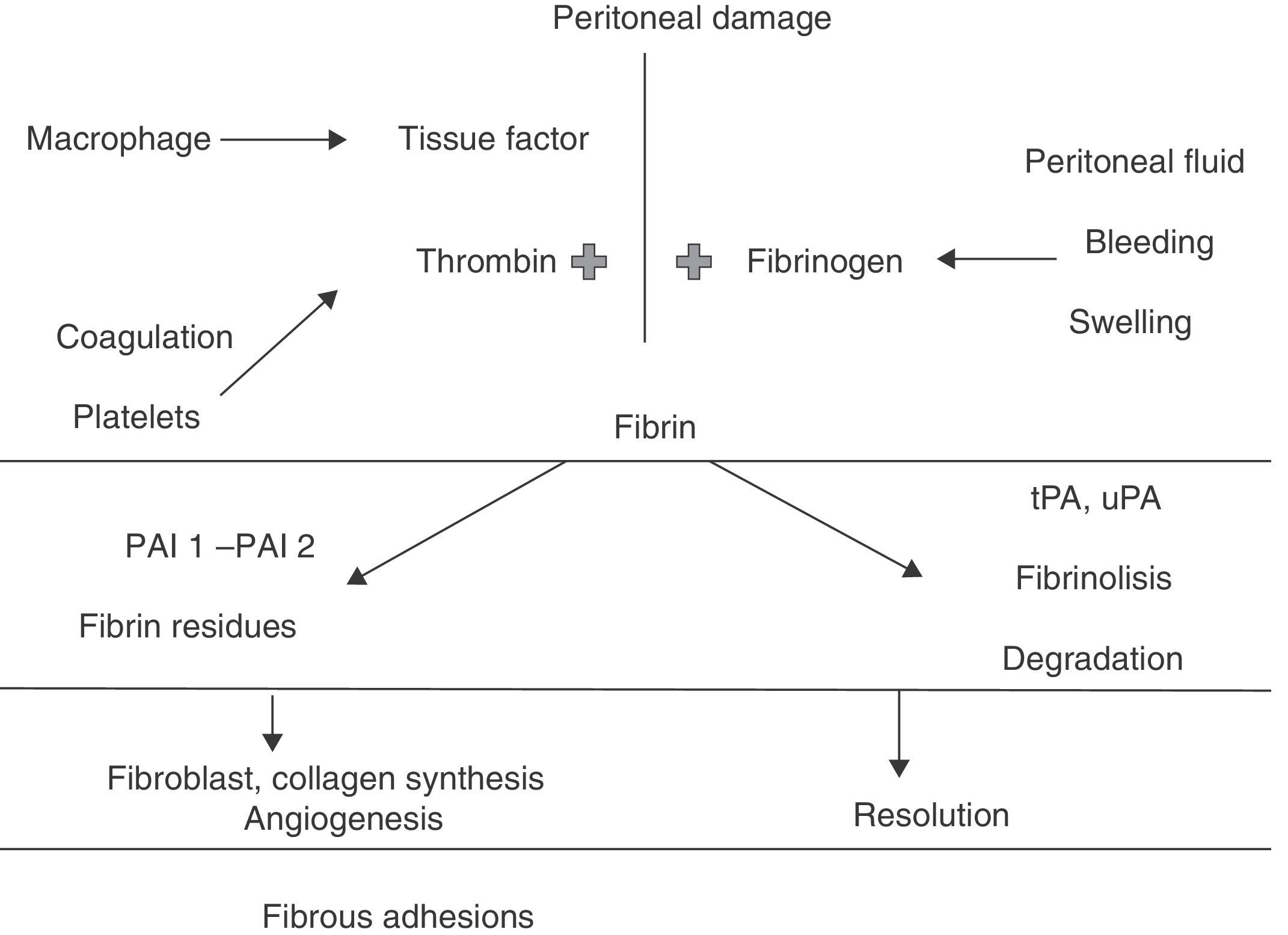

PathophysiologyRepair of the peritoneal tissue is a complex process that involves different types of cells, cytokines, coagulation factors and proteases, all acting together to restore tissue integrity.23 A complex interaction of biochemical events involved in tissue repair, such as inflammation and angiogenesis, control the adherence formation process, as well as other factors such as loss of the existing surfactant in the abdominal cavity between the intestinal loops.24

It is highly accepted that the fibrinolitic system plays a key role in the postoperative peritoneal healing. Immediately after a surgical injury in the peritoneum, bleeding occurs and an increase in the vascular permeability with extravasation of liquid rich in fibrinogen develops.24,25 Almost simultaneously, an inflammatory response appears, with the migration of inflammatory cells, release of cytokines and activation of the coagulation cascade. The activation of the coagulation system results in the formation of thrombine, which is necessary for the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin.23,26

Inflammatory mediators can also play a central role in the formation of adherences. There is experimental evidence showing that certain mediators, such as the transforming growth factor B and interleukins, decrease the fibrinolitic capacity of the peritoneum and increase adhesion formation.27

Fibrin restores the injured tissue, and once generated, it is deposited along the peritoneal surfaces. Fibrin is a sticky substance that causes the adherence of organs or injured serous surfaces to become fused.28 Under normal circumstances, the formation of a fibrin matrix during a wound healing process is just temporary, and the degradation of those weak fibrinose adherences by proteases locally released by the fibrinolitic system occurs within 72h after the occurrence of the injury (Fig. 1). Thus, the fibrinolisis process is not confined to the degradation of intravascular thrombi; it also has a central role in tissue remodellation and repair.23 Fibrinolisis allows mesothelial cells to proliferate and peritoneal defect to be restored within 4–5 days, preventing permanent fixation of the adjacent surfaces.29 Adequate blood flow is critical for fibrinolisis and as the peritoneal injury results in ischaemia, this also interferes with fibrinolisis. If it does not occur within 5–7 days after the peritoneal injury, or if local fibrinolitic activity is reduced, the fibrin matrix persists.23 In that case, the temporary fibrin matrix gradually becomes more organised as the collagen-secreting fibroblasts and other repairing cells infiltrate the matrix.28 Organisation based on the fibrin takes time and their transformation into mature fibrous adherences allows them to persist.

PreventionEvery prevention strategy should be safe, effective, practical and profitable. A combination of prevention strategies can be more effective, but the state of knowledge on the subject is fairly limited.

Surgical techniqueFirstly, the laparotomy approach shall be considered compared to laparoscopy. Laparoscopy is believed to diminish the formation of adherences due to the decrease in peritoneum trauma. Two prospective, randomised studies on postoperative obstructions have been carried out, to compare laparoscopy and laparotomy in relation to colorectal surgery.30 Both studies showed no difference in the postoperative obstruction rate. In Taylor et al.22 study where the subjects from the CLASICC trial were followed-up, the highest obstruction rate was observed in those subjects requiring conversion.

Other technical considerations, apart from the surgical approach, refer to soft tissue handling, good haemostasis and peritoneum closure suppression. There are two randomised trials in the gynaecological literature that would support this30 and would avoid the use of surgical gloves with talc.31

HydroflotationThe main idea entailed by hydroflotation is to separate the peritoneal surfaces during the initial healing phase to prevent the formation of adherences. Crystalloid solutions, such as Ringer's lactate, have been introduced in the peritoneal cavity with the hope of obtaining this benefit.

In fact, these solutions are absorbed within 24h, and probably due to this short duration, they have not been proven to reduce adhesions; on the contrary, it has been previously shown that saline solutions initially condition a severe inflammatory process with an increase in polymorphonuclears.22,31

Instillation of chemical compoundsCurrently, icodextrin 4% (Adept) is the only chemical product approved for this indication by the US Food and Drugs Administration (FDA). One litre of the solution is instilled and remains in the abdomen at the conclusion of surgery, aiming at the separation of the damaged peritoneal surfaces from other structures during the initial postoperative period, when the formation of adherences would occur. In a gynaecological literature trial with 402 patients randomly assigned during the laparoscopic surgery, Adept's or Ringer's lactate solution instillation were applied. In a second laparoscopy performed 4–8 weeks later, fewer adherences were detected and fertility was found to be significantly better in the Adept group.

A controlled, randomised trial has been recently carried out in 180 patients who underwent laparotomy due to intestinal obstruction, and they were followed up to determine whether the use of Adept might reduce the incidence, scope and severity of adhesions. Strangely, the small intestine obstruction incidence was lower in the Adept group, but there was no difference regarding the need of a laparotomy caused by small intestine obstruction, with a follow-up mean of 3.5 years. In addition, there was no significant difference in the severity of adherences.32

Another proposed agent was ferrous hyaluronate 0.5% (Intergel). A controlled, randomised trial to examine the colorectal pathology and its evolution was designed and the sample size estimation was 200 cases. Thirty-two patients were later added and the study was discontinued due to postoperative complications related to a higher rate of postoperative ileum and anastomotic leaks in the Intergel group.22 It is currently not available for use in the US market for colorectal procedures.32

GelsSprayGel is a pulverisable gel that persists 5–7 days and is then absorbed. It is a more viscous solution compared to Adept, aiming at providing an improved barrier to adherence formation. A small randomised trial was carried out with loop ileostomy closure. SprayGel was compared with a group lacking any type of anti-adherent barrier. Investigators concluded that adherences and surgical time were significantly reduced with the use of SprayGel. Another randomised trial with 66 subjects was carried out by a group of gynaecologists who compared adherences formation with re-evaluation laparoscopy after the open or laparoscopic uterine myomectomy using SprayGel in the intervention group. This study also found a lower adherence index. Despite these studies, and others showing certain efficacy, SprayGel has been removed from the market due to the late onset of postoperative pain and reactions to a foreign body. There are currently no other gels for the prevention of adherences.33

BarriersThe most commonly used mechanical barriers are the hyaluronic acid films in a carboxymethylcellulose framework (Seprafilm; Genzyme Corporation, Cambridge, MA, USA), oxidised cellulose (Interceed; Ethicon Division by Johnson & Johnson, Arlington, TX, USA), and non-absorbable meshes, which main advantage is the creation of a fixed barrier of known duration, and the disadvantage is that it is only effective when applied. In a laparoscopically treated case, a barrier such as Seprafilm can also be technically difficult to apply, and Seprafilm does not currently have FDA indication for use in laparoscopical procedures.34

In the Oxidative Stress laboratory at Escuela Superior de Medicina, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, a study was carried out with 32 rats to which were applied several of these agents, and were compared with a ClO2 solution, which has been proven to inhibit adherences formation; this substance is a well-known potent antiseptic agent. The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of ClO2 in the reduction, prevention and innocuousness of postoperative adherence formation and to compare it with other anti-adhesion agents approved by the FDA and widely distributed in the market. In the ClO2 group, the adherence index and the number of adherences were lower compared to the control group (p<0.05). Neither Guardix nor Inteceed groups showed any modification in the number or index of adherences compared to the control. The histological analysis showed similar changes in fibroblasts, capillaries, peripheral fibrosis and basophils in all groups. This study demonstrated that ClO2 is a safe substance that in adequate concentrations prevents adherences and, consequently, avoids to some extent the occurrence of symptoms of intestinal obstruction requiring surgery, which when present are less strong and easily detachable.

Wound closureIn the mid-line wounds closure, the layers to consider are fascia, subcutaneous fat and skin. Many studies have been performed considering the optimal fascia closure for laparotomy. Five systemic reviews and 14 trials were assessed in a literature review in 2010.35 Largely based on the results from almost 8000 subjects, the optimal closure is a continuous functioning technique with slow absorption suture material, although results were not conclusive in emergency situations.

An interesting study has challenged the measure of 1cm width for conventional sutures taken at the fascia. Millbourn et al.35 analysed 737 subjects in a group with wound closure and fascia sutures of at least 10mm or a group with suture closures between 5 and 8mm from the fascia border (using PDS suture). The study detected a significantly lower rate of infection in the surgical site (5.2 vs. 10.2%), and the post-incisional herniation rate (5.6 vs. 18%) in the group with the lower number of sutures.36–38

Regarding the subcutaneous layer, closure is generally considered in obese patients. Cardosi et al.39 randomly analysed 225 patients with 3cm or more of vertical adipose tissue in mid line wounds in three groups: Camper fascia approximation suture, closed suction drainage, or no intervention (control group). No difference was found in the wound complications. In another controlled, randomised study developed by Paral et al.40 415 subjects were randomly assigned to the group of subcutaneous cellular tissue suture or the no intervention group. No differences were observed regarding infectious or non-infectious complications. In general, it seems that the additional time spent for subcutaneous fat suture does not lead to better results.

Skin closure with staples, mostly due to a lower infection rate, and faster time for wounds closure, seems to be the best option.41

Tissue adhesives are a relatively new skin closure method that prevents the use of needles and does not require elimination. In 2010, a Cochrane review examined tissue adhesives in the closure of surgical wounds. There was a total number of results from 1152 subjects in 14 randomised trials. Despite the supposed advantages of adhesives, sutures have been found to present a lower dehiscence rate.42,43

ConclusionsThe development of postoperative adherences is an increasingly recognised cause of complications, ranging from pain to intestinal obstruction, which frequently require surgical interventions which, apart from being expensive, risk the patient's life and health. In general, adherences are diagnosed in a “second examination” using laparotomy, which is frequently inadequate and late. The incidence and severity of postoperative adherences vary based on the type of surgery and procedure. Gastrointestinal surgery and myomectomy have the highest rate of postoperative adherence formation, while urologic and caesarian surgeries have the lowest rates. Gastrointestinal laparoscopic surgery is the only surgical modality used to reduce the incidence at the minimum, as well as the adherence severity that can lead to the decrease in complications and improve recovery. In addition, the results of modern surgery bring to light an improvement in the global incidence of adherences compared to surgery 30 years ago; this may reflect improvements in surgical practice and education, apart from the development of minimally invasive surgery.

These results can be even more improved by applying anti-adherence films and pharmacotherapies, such as hyaluronic acid/carboxymethylcellulose, regenerated and expanded oxidised cellulose 0.5% in ferric hyaluronate or the still experimental use of chlorine dioxide. Also, experimental biological research on adhesion can provide a greater comprehension of the molecular mechanisms underlying the formation of adherences; this can lead to new strategies for the prevention and treatment of postoperative adhesions.

The high rate of postoperative adherences justifies the introduction of increasingly innovative strategies for the reduction of adherences, to improve patients’ morbidity and mortality, as well as the cost of abdominal surgery.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Correa-Rovelo JM, Cleva Villanueva-López G, Medina-Santillan R, Carrillo-Esper R, Díaz-Girón-Gidi A. Obstrucción intestinal secundaria a formación de adherencias postoperatorias en cirugía abdominal. Revisión de la literatura. Cir Cir. 2015;83:354–351.