Family business scholars assume that family business goals represent the nature of the firm's decision making and are driving forces (i.e., antecedents) of family firm behavior, performance, continuity, competitiveness, and sustainability. Without measuring family business goals, family business research—specifically, the family business theorizing process—is floating in the midst of assumptions used to justify observational descriptive data, such as differences between family and non-family firms and differences among various types of family firms. There remains a lack of clarity surrounding the theoretical definition of family business goals and an absence of methodological approaches to make the concept operative. In order to address this gap, this research applies an exploratory step-by-step methodology that combines both a theoretical and an empirical approach. First, following an inductive literature review, I theorize family business goals as a multidimensional concept combining two scales: economic versus non-economic orientation and family versus business orientation. Second, by using a unique Spanish database of family business, I use the partial least squares structural equation modeling method to confirm and extend the proposed theoretical multidimensional concept of family business goals.

One of the main challenges that the family business field had to address was gaining external legitimacy in social science (Pérez Rodríguez and Basco, 2011), but this research stream is still in the adolescent stage (Gedajlovic et al., 2012). External legitimacy is a necessary but insufficient condition for achieving a mature stage of knowledge development, which requires a theory—a family business theory—to explain, describe, and predict the object of study (Basco, 2015). The most common method for achieving legitimacy was to apply mainstream theories and approaches to family business samples in order to understand the object of study (i.e., the borrowed-research strategy). Despite knowledge advancement, the field is still phenomenologically driven because of this strategy. Specifically, the borrowed-research strategy has created a general consensus that the family is responsible for the distinctive behavior of family firms,1 but the observable differences between family and non-family firms and among types of family firms are assumed to be produced by specific family business goals and motivations.

The literature review shows that family business scholars have justified differences in firm goals because of the meaning that family members give to the firm, for instance, emotional ownership (Pieper, 2010). This posture shifts the aim of the firm itself from purely profit maximizer to utility maximizer. This shift changes the traditional profit-maximization model of the firm as an efficient black box to a human institution with different possible meanings. The latter posture leads to a broad variety of goals emerging, making the family firm unique and guiding the way resources are created, organized, and allocated—namely, an idiosyncratic decision-making process arises (Carney, 2005).

Family business goals have been studied since the nascent stage of the family business field (e.g., Astrachan and Jaskiewicz, 2008; Dunn, 1995; Lee and Rogoff, 1996; Tagiuri and Davis, 1992; Westhead and Howorth, 2007). However, there remains a lack of clarity surrounding the theoretical definition of family business goals and an absence of methodological approaches to make the concept operative (Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2014). Consequently, family business research is mainly operating under presumptions regarding the specific goals that families incorporate into the firm—namely, objectives that have hardly been tested but may affect family firm behavior. Even though there are some exceptions (e.g., Kim and Gao, 2013) that attempt to measure family firms goals, these measures are incomplete and only combine proxy items (e.g., see Zellweger et al., 2013) without providing a systematic interpretation of the concept of family business goals.

This article proposes that the theory-building process for family business research needs to increase knowledge on the emerging goal patterns of two different logics—family logic and business logic—by incorporating new conceptual (Pearson and Lumpkin, 2011), relational (Reay and Whetten, 2011), and methodological perspectives (Wilson et al., 2014). In order to address this gap, I approach the phenomenon (i.e., family business goals) as it relates to the interaction between the family and business logics by applying an inductive research method. The aim is to create an exploratory step-by-step methodology combining both a theoretical approach and an empirical approach. This methodology attempts to define concepts, explore data, and determine to what extent theoretical representations are supported by empirical data from real life.

In the first step, using an inductive theoretical interpretation, I theorize family business goals as a multidimensional concept formed by economic and social aspects that combines two scales: economic versus non-economic orientation and family versus business orientation. In the second step, using an inductive empirical approach, I operationalized the proposed multidimensional concept of family business goals. Because the research aim is exploratory in nature, both factor analysis and partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) were used to explore the data (Hair et al., 2012a), which was composed of 25 goals. The empirical exploration confirms and extends the proposed multidimensional concept of family business goals.

This research makes several contributions. Regarding academic contributions, this article has theoretical and methodological implications. First, this article addresses the call made by Miller and Le Breton-Miller (2014) about the current limitation in family business research of putting multiple priorities for family firms under the same umbrella of “socio-emotional wealth.” In this sense, this study is important for the theory-building process because it theorizes about the dimensionality of family business goals by considering for whom goals are important and the specific contexts created by the family-business relationship. Second, this article attempts to address the need for the family business field to develop operative concepts by ensuring the measurement accuracy of constructs/dimensions (Pearson and Lumpkin, 2011), specifically relating to the need to find multifaceted and fine-grained measures of priorities or goals (Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2014). Empirically, this study selects and combines a set of measures and defines specific methods to validate the concept of family business goals. Finally, this article theoretically and empirically answers the question of what makes family firms behave differently by addressing Carney et al.’s (2015) suggestion that studying family firm behavior (e.g., strategic choices) and firm performance requires researchers to analyze firms’ economic and non-economic preferences. Therefore, by focusing on family business goals, this article sheds some light on testing the assumptions of family priorities and objectives in the firm, which may explain differences between family and non-family firms as well as among types of family firms.

This research also has practical implications for family owners, family members working in family firms, practitioners, and non-family minority investors in family firms because it provides a framework to understand the constellation of family business goals along two different scales: economic/non-economic orientation and business/family orientation.

This paper is organized as follows. Next, I briefly explain the importance of family business goals for family business research as a way to position this study. Then, I develop the methodological part of the article by presenting the exploratory theoretical approach for defining family business goals as well as the exploratory empirical approach for operationalizing the concept of family business goals. Finally, the article ends with a discussion and conclusion section, in which I present theoretical and practical implications, limitations, and future research lines.

Family business goalsThe most common definition of family business is the one originally proposed by Chua et al. (1999), which is an extension of the principles derived from the behavioral theory of the firm (Cyert and March, 1963): “the family business is a business governed and/or managed with the intention to shape and pursue the vision of the business held by a dominant coalition controlled by members of the same family or a small number of families in a manner that is potentially sustainable across generations of the family or families.” This definition has some important characteristics that combine demographic perspectives (i.e., by defining the family firm as the explicit materialization of family participation within the firm, such as dominant family coalition) and behavioral perspectives (i.e., by defining the family firm as the intrinsic materialization of family influence on the firm, such as governance, management vision, and sustainability).

The abovementioned definition considers that the family's influences and effects are manifested in governance and management decision making, firm vision, and sustainability. To move the study of family business further, it is necessary to deepen our understanding of the implicit phenomena of family business—namely, the juxtapositions and collisions among family, business, and societal logics that define the organization's focus of attention and goal schema (Thornton et al., 2012). In this context, priorities and goals may determine—to some extent—firm behavior and performance. That is, the priorities that individuals collectively assign to the firm determine the destiny of the family firm. For instance, this is what Miller and Le Breton-Miller (2006) and Miller et al. (2011) mainly argued when they proposed that family firm goals affect resource allocation. A similar thesis was proposed by Gomez-Mejia et al. (2011), who argued that socio-emotional wealth dimensions my affect firm behavior and firm performance. Several other researchers applied this premise to their models, including, for instance, Chrisman et al. (2014) and Zellweger et al. (2013), among others. Consequently, family business goals matter.

Even though family business goals have been studied since the nascent stage of the family business field (Dunn, 1995; Lee and Rogoff, 1996; Tagiuri and Davis, 1992; Westhead and Howorth, 2007), there is a lack of theoretical integration when it comes to defining the concept of family business goals. Therefore, the basic question is as follows: what does “family business goals” mean? This call was raised by Miller and Le Breton-Miller (2014), who argued that the way family business goals are measured and incorporated into theoretical models is still puzzling. Such limitation is challenged by the unobservable nature of goals—namely, they cannot be observed directly in real life, as for example it is the goal “Good reputation in the business community” which is an unobservable aspect. Therefore, the study of family business goals has to deal with unobservable constructs.

In order to address the aforementioned gap, this research approaches family business goals by theoretically considering the juxtaposition of family and business logics and by applying an inductive research method. The methodology was divided in two main steps, which are presented in the next section. In the first step, I explored the existing literature to better understand the current knowledge about family business goals. This literature review leads to the development of a multidimensional concept of family business goals based on the nature of goals themselves (i.e., orientation). In the second step, I use the theoretical concept as a frame to explore empirical data about family business goals using a sample of Spanish family firms. The aim of the latter section is to verify the match of the empirical representation of family business goals with the theoretical proposed discourse.

Theoretical exploratory approachFamily business goals as a multidimensional conceptStakeholder theory has been used to demonstrate that family firms not only serve the interests of multiple parties, such as employees, suppliers, and communities (Freeman, 1984), but also the interests of one important actor: the family (Cennamo et al., 2012; Zellweger and Nason, 2008). In this sense, when stakeholder theory is used in its descriptive form (Donaldson and Preston, 1995), family firm is defined as a set of different stakeholder interests and demands with particular intrinsic values and goals. Therefore, like any other firm, family firms have goals resulting from the influence of owner-managers’ environmental, organizational, and entrepreneurial contexts (Raymond et al., 2013) and the family context.

The family's influence on shaping firm goals is not homogenous. The family is not a monolithic group of people with similar demands. Within the family system, not only are there family members who actually manage and control the family firm but also family members who are de facto owners of the firm but are not involved in everyday decision making. At the individual level, it is possible to express the family's influence on firm goals by considering how different family members—based on their own goals and their own positions in the family and in the business—can alter family business goals (Kotlar and De Massis, 2013). This notion brings us to consider using an institutional logic approach as an umbrella to understand family business goals. Thornton and Ocasio (1999, p. 804) defined institutional logic as “the socially constructed, historical patterns of material practices, assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules by which individuals produce and reproduce their material subsistence, organize time and space, and provide meaning to their social reality.” Indeed, institutional logic frames the means and ends of individual behavior (Friedland and Alford, 1991). Specifically, individuals are embedded in interactions based on collective identities that are formed by cognitive, normative, structural, and emotional connections. When collective identities are institutionalized within a group, they generate a specific institutional logic.

Therefore, the dominant institutional logics in which individuals are embedded may act as a force determining family business goals. There are at least three institutions that have different roots: business logic, community logic, and family logic. These logics guide individuals in their actions, and because of the importance of family members within their firms, they transmit the weight of the institutional logic's footprint into the organization by defining types of internal and external relationships and the ways power and status are distributed. These micro-foundation processes (Thornton et al., 2012) imply that individuals’ (e.g., family members’) being embedded in multiple logics activates goals that focus their attention and thus determine organizational decision making. Therefore, the conditions for success and survival as well as change or stability come when the firm is able to legitimize its position in its environment by shaping organizational behavior (Tolbert and Zucker, 1983), thus making family firms different from non-family firms because of the specific logics available to individuals.

The constellation of goals that emerge at the firm level based on different logics is produced by the fuzzy boundaries among the family, the firm, and the external environment. Therefore, not only do goals in family firms combine the traditional discrimination between economic and non-economic aspects (responding to different stakeholder logics), but the nature of this classification is also demarcated by an underlying orientation based on family logic and business logic—that is, business orientation or family orientation. This juxtaposition is rooted in the fact that the family—as an owner and dominant group inside the firm—not only invests economic resources but also social and emotional resources. In this context, family firms are committed to the preservation of economic wealth and socio-emotional wealth (Berrone et al., 2012). The latter is defined as non-financial aspects of the firm that meet the family's affective needs (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). The socio-emotional wealth dimension is important because it is the essence of family business goals (Zellweger et al., 2013).

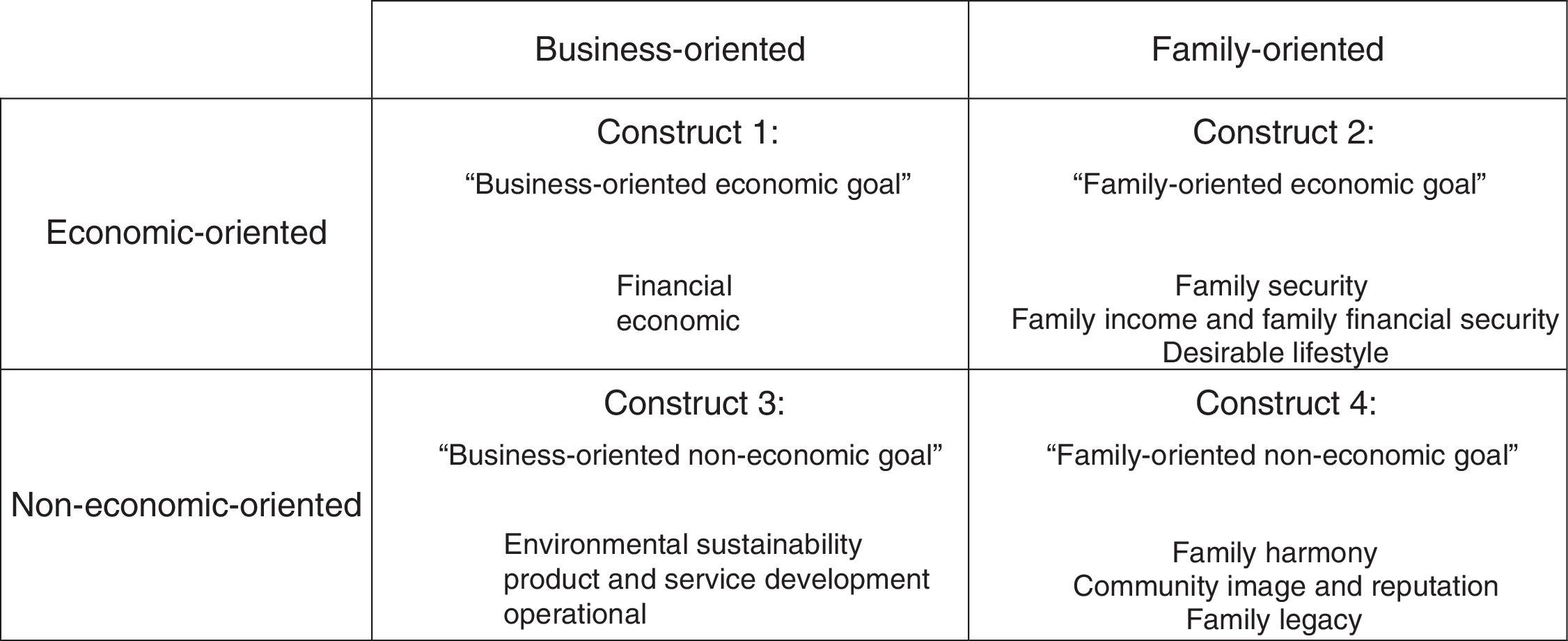

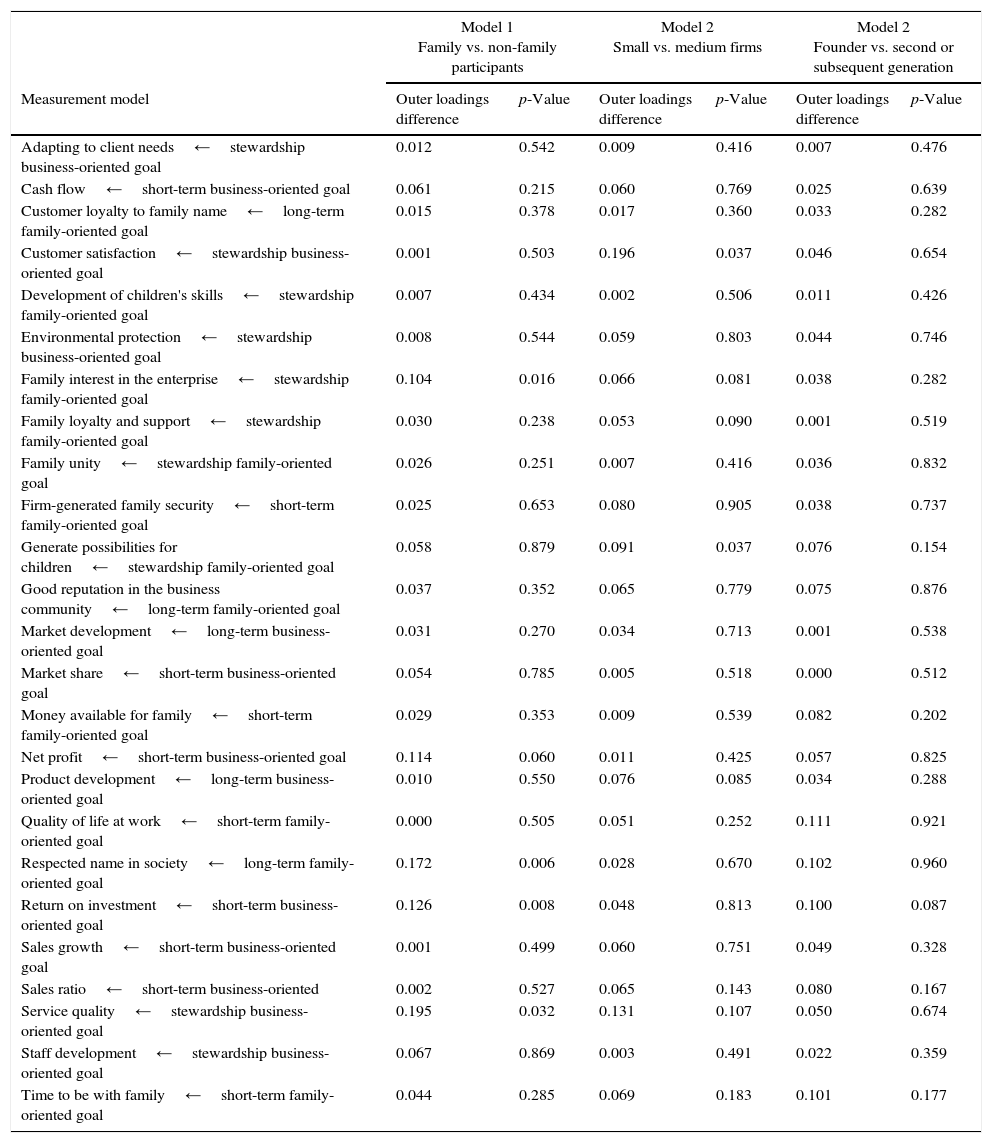

Consequently, it can be argued that in family firms, economic and non-economic goals are combined with specific orientations, such as family and business orientations. Based on this demarcation, a multidimensional concept of family business goals between an economic versus non-economic orientation and a family versus business orientation can be formed. Using this frame, I review the current literature on family business goals to classify them. Fig. 1 shows the results of this process.

The proposed lens based on economic/non-economic and business/family parameters leads to the argument that the concept of family business goals is intrinsically multidimensional and covers a wide range of aspects. Therefore, the first research statement:

Research Statement 1: The underlying structure of family business goals shows that there are four different inter-related constructs at an abstract level combining economic versus non-economic orientation and family versus business orientation.

If the above proposition is empirically tested and corroborated, this would give some clue about the multidimensionality of family business goals as a concept but not enough evidence for construct validity. Therefore, the subsequent step is to strengthen the operational level of the concept by systematically analyzing construct validity. Therefore, the second research statement is as follows:

Research Statement 2: The proposed concept of family business goals has to successfully pass four criteria: reliability, convergent validity, discriminant validity, nomological validity, and content validity.

In this section, the analysis is shifted from an inductive method based on a theoretical exploratory approach to an indicative method based on an empirical exploratory approach. The aim of this second step is to explore empirical data and to see to what extent the data fits the proposed model.

Population and sampleBefore explaining the empirical exploratory approach, I describe the data used in the analysis. The Spanish context was used to test the concept of family business goals. The data for this research came from a unique study on Spanish family firms. Spain is representative of the Latin European culture (Gupta and Levenburg, 2010), for which the family serves as an important social and economic actor (Colli et al., 2003) that affects family firms.

Because there is no directory of family firms in Spain, the family firms had to be identified in an ex-post analysis (Claver et al., 2009) based on specific demographic aspects. To be considered a family business, the firm had to meet one of the two criteria based on the premise of “family participants in business,” which has been used by other studies (see the literature review made by Basco, 2013): (1) at least 51% of firm ownership is in the hands of members of the same family and/or (2) more than one family member works on the board or in management positions. Regarding firm size, firms with 50–500 employees were chosen (other studies consider similar ranges for small- and medium-sized firm, such as Leitner and Güldenberg, 2010).

The criteria mentioned above were applied to two databases: Sistema de Análisis de Balances Ibéricos (SABI) and Dun & Bradstreet (DUN). From an original dataset of 16,000 Spanish firms in the chosen size range, 4450 firms met the family criteria.2 A stratified random sample was used, with stratification variables comprising the sector of economic activity and the autonomous community (i.e., first-level political division of Spain). Before the final questionnaire was sent, academic and family business experts (e.g., managing directors, chief executive officers [CEOs], and directors who helped during the pre-test) were asked for their analysis, reinforcing the validation process. In total, 732 firms responded to the survey between July and October 2004—a rate of 16.45%, which is similar to other studies in the Spanish context (Arosa et al., 2010). A chi-square analysis and student analysis confirmed that there were no significant differences between the sample and the population in relation to firms’ legal format, sector of economic activity, location, or number of employees. The average business was 25 years old and had a staff of 110 employees. Seventeen autonomous regions and 23 sectors of economic activity were included.

Empirical research designIn the theoretical exploratory approach, the meaning of the concept was framed as being multidimensional. This section attempts to analyze the correspondence between the theoretical framework and empirical evidence. To address this aim, I followed a sequence of steps to explore the concept of family business goals.

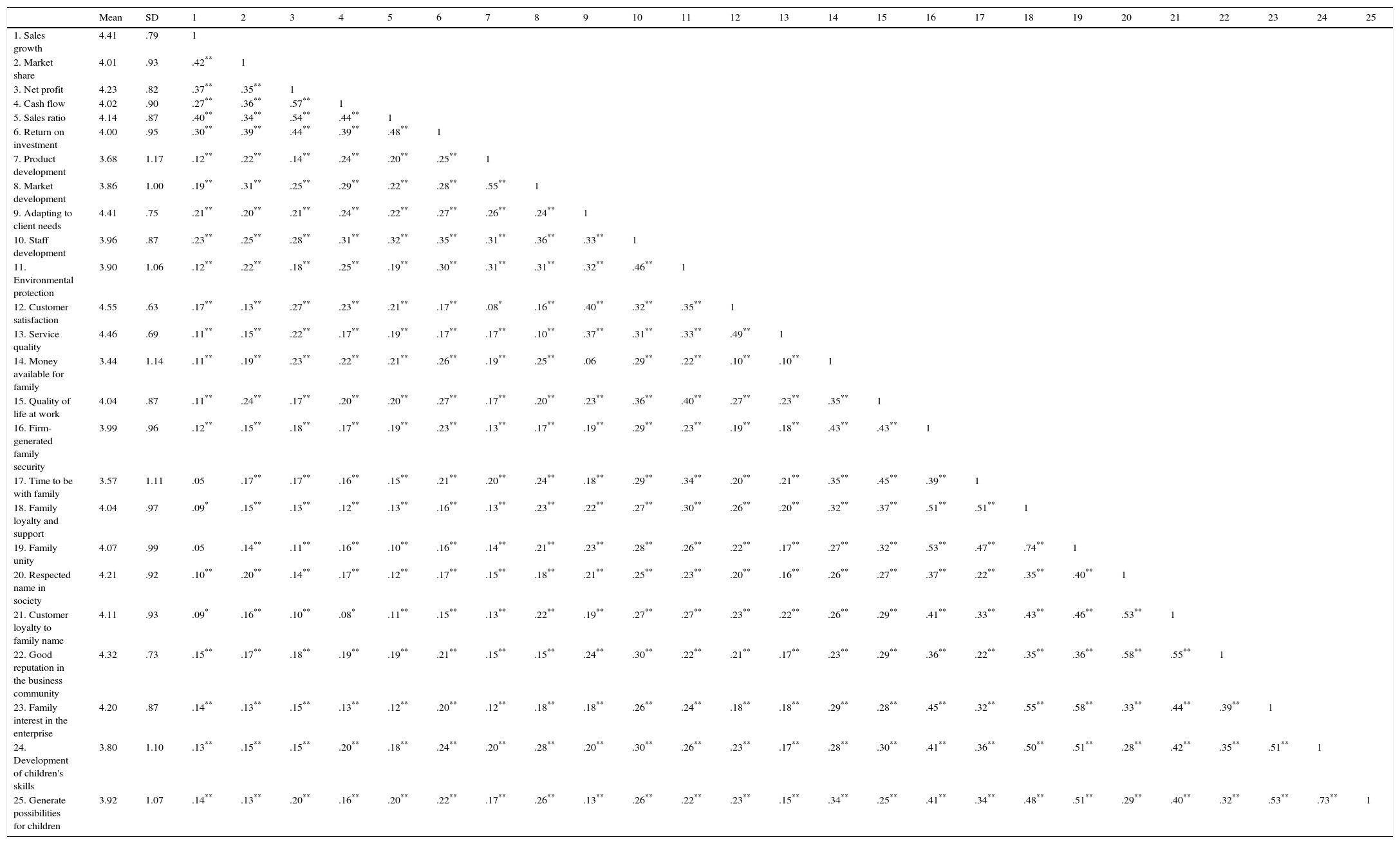

As was explained in the previous section, family business goals are an unobservable concept, but they can be identified by combining an economic versus non-economic orientation and a family versus business orientation. To capture the meaning of the concept, it was necessary to define a set of items (i.e., indicators) (C. C. Miller et al., 2013a)—namely, aspects that capture subjective characteristics of the concept in respondents’ answers to particular questions. In this exploratory section, 25 items (see Table 1) representing potential family firm goals were used. Items were obtained from different sources (e.g., Gupta and Govindarajan, 1984; Hienerth and Kessler, 2006; Lee and Rogoff, 1996; Sorenson, 1999; Venkatraman and Ramanujam, 1987; Westhead and Howorth, 2007). The importance of each goal item was measured on a five-point Likert scale (anchored at 1=very little importance to 5=extremely important).

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix.

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sales growth | 4.41 | .79 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Market share | 4.01 | .93 | .42** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Net profit | 4.23 | .82 | .37** | .35** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Cash flow | 4.02 | .90 | .27** | .36** | .57** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Sales ratio | 4.14 | .87 | .40** | .34** | .54** | .44** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. Return on investment | 4.00 | .95 | .30** | .39** | .44** | .39** | .48** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Product development | 3.68 | 1.17 | .12** | .22** | .14** | .24** | .20** | .25** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 8. Market development | 3.86 | 1.00 | .19** | .31** | .25** | .29** | .22** | .28** | .55** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 9. Adapting to client needs | 4.41 | .75 | .21** | .20** | .21** | .24** | .22** | .27** | .26** | .24** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 10. Staff development | 3.96 | .87 | .23** | .25** | .28** | .31** | .32** | .35** | .31** | .36** | .33** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 11. Environmental protection | 3.90 | 1.06 | .12** | .22** | .18** | .25** | .19** | .30** | .31** | .31** | .32** | .46** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 12. Customer satisfaction | 4.55 | .63 | .17** | .13** | .27** | .23** | .21** | .17** | .08* | .16** | .40** | .32** | .35** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 13. Service quality | 4.46 | .69 | .11** | .15** | .22** | .17** | .19** | .17** | .17** | .10** | .37** | .31** | .33** | .49** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 14. Money available for family | 3.44 | 1.14 | .11** | .19** | .23** | .22** | .21** | .26** | .19** | .25** | .06 | .29** | .22** | .10** | .10** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 15. Quality of life at work | 4.04 | .87 | .11** | .24** | .17** | .20** | .20** | .27** | .17** | .20** | .23** | .36** | .40** | .27** | .23** | .35** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 16. Firm-generated family security | 3.99 | .96 | .12** | .15** | .18** | .17** | .19** | .23** | .13** | .17** | .19** | .29** | .23** | .19** | .18** | .43** | .43** | 1 | |||||||||

| 17. Time to be with family | 3.57 | 1.11 | .05 | .17** | .17** | .16** | .15** | .21** | .20** | .24** | .18** | .29** | .34** | .20** | .21** | .35** | .45** | .39** | 1 | ||||||||

| 18. Family loyalty and support | 4.04 | .97 | .09* | .15** | .13** | .12** | .13** | .16** | .13** | .23** | .22** | .27** | .30** | .26** | .20** | .32** | .37** | .51** | .51** | 1 | |||||||

| 19. Family unity | 4.07 | .99 | .05 | .14** | .11** | .16** | .10** | .16** | .14** | .21** | .23** | .28** | .26** | .22** | .17** | .27** | .32** | .53** | .47** | .74** | 1 | ||||||

| 20. Respected name in society | 4.21 | .92 | .10** | .20** | .14** | .17** | .12** | .17** | .15** | .18** | .21** | .25** | .23** | .20** | .16** | .26** | .27** | .37** | .22** | .35** | .40** | 1 | |||||

| 21. Customer loyalty to family name | 4.11 | .93 | .09* | .16** | .10** | .08* | .11** | .15** | .13** | .22** | .19** | .27** | .27** | .23** | .22** | .26** | .29** | .41** | .33** | .43** | .46** | .53** | 1 | ||||

| 22. Good reputation in the business community | 4.32 | .73 | .15** | .17** | .18** | .19** | .19** | .21** | .15** | .15** | .24** | .30** | .22** | .21** | .17** | .23** | .29** | .36** | .22** | .35** | .36** | .58** | .55** | 1 | |||

| 23. Family interest in the enterprise | 4.20 | .87 | .14** | .13** | .15** | .13** | .12** | .20** | .12** | .18** | .18** | .26** | .24** | .18** | .18** | .29** | .28** | .45** | .32** | .55** | .58** | .33** | .44** | .39** | 1 | ||

| 24. Development of children's skills | 3.80 | 1.10 | .13** | .15** | .15** | .20** | .18** | .24** | .20** | .28** | .20** | .30** | .26** | .23** | .17** | .28** | .30** | .41** | .36** | .50** | .51** | .28** | .42** | .35** | .51** | 1 | |

| 25. Generate possibilities for children | 3.92 | 1.07 | .14** | .13** | .20** | .16** | .20** | .22** | .17** | .26** | .13** | .26** | .22** | .23** | .15** | .34** | .25** | .41** | .34** | .48** | .51** | .29** | .40** | .32** | .53** | .73** | 1 |

The methodological inductive approach comprised two steps. The procedure started by carrying out an exploratory factorial analysis with the aim of examining the underlining relationships of 25 family business goals (i.e., items). This technique helped determine the emerging constructs/dimensions (i.e., item groupings) based on the empirical data. Then, the results from the exploratory factorial analysis were used to evaluate the correspondence between the empirical model and the proposed theoretical model. Therefore, this analysis served to test Research Statement 1.

To strengthen the analysis, the exploratory factorial analysis was complemented with a second-generation multidimensional analysis. PLS-SEM was used to analyze the construct validity of the dimensions that emerged from the factorial analysis because its strength as an exploratory technique (Hair et al., 2012a,b; Wold et al., 1984) suited the research aim (i.e., to discover the dimensionality of the family business goal concept). The traditional process of construct validation was performed by evaluating four aspects (Hair et al., 2010; Hamann et al., 2013): reliability, convergent validity, discriminant validity, nomological validity. Additionally, content validity was also analyzed.

ResultsTable 1 shows the descriptive information and correlation of family business goal items. The exploratory analysis based on visual inspection shows that there are two pairs of items that are highly correlated: (1) family loyalty and support and family unity and (2) development of children's skills and possibilities for children. These results highlight potential problems for construct validity because they indicate that items are capturing the same information—namely, the items overlap in capturing specific aspects of the concept of family business goals. Therefore, to a certain extent, there is redundant information.

Exploratory factorial analysisAs was explained in the research design section, the next step was to carry out a principal components analysis to explore the underlying structure of the set of items and to determine the types of constructs/dimensions that emerge from the empirical data. I used Varimax rotation to identify constructs because it more clearly separates the constructs, thereby simplifying the interpretation (Hair et al., 2010). In the first analysis, there was one item (i.e., cost-reduction goal) with a commonality of less than .30. This means that very little of this item is taken into account in the final factor solution (Hair et al., 2010). Therefore, this item was eliminated, and the exploratory factorial analysis was performed again. In the subsequent analysis, without the cost-reduction goal item, all items had commonality values higher than .47, which is considered acceptable for an exploratory study (Hair et al., 2010).

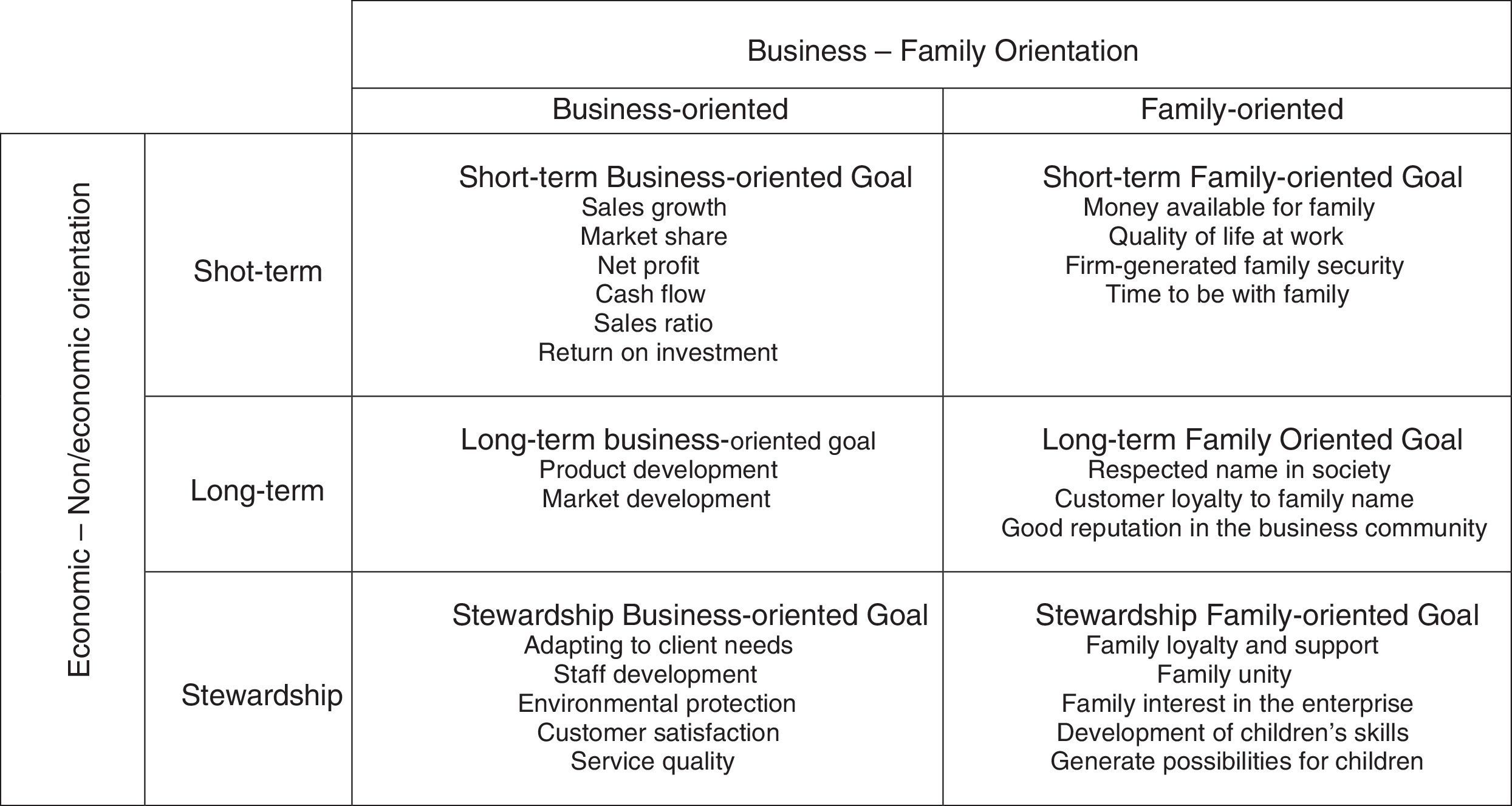

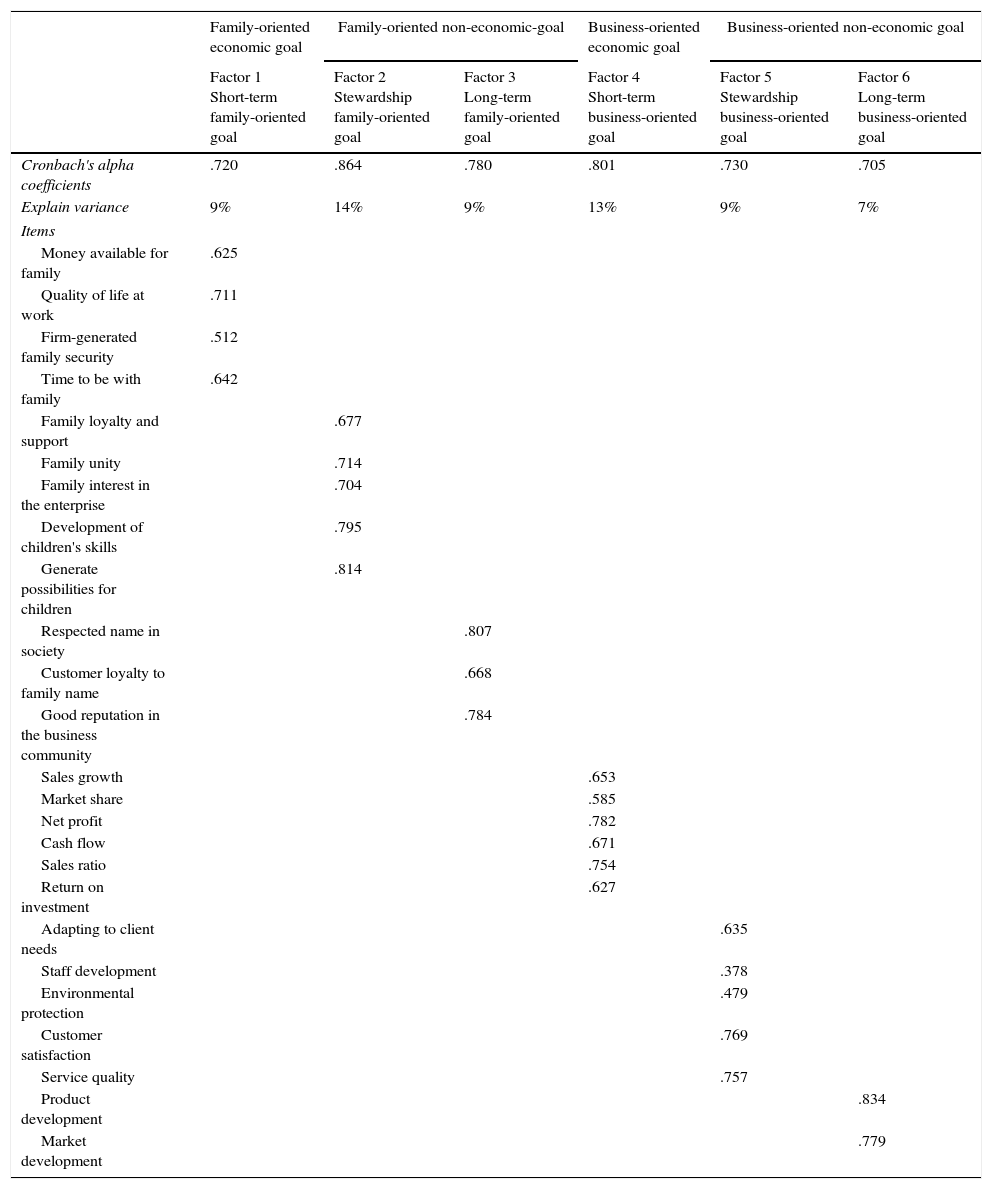

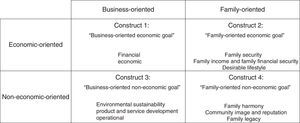

To interpret the constructs/dimensions that emerged, I used the factor loading value—that is, those items with a factor loading of around .50 or above were analyzed for reliability. Table 2 shows that six constructs/dimensions emerged from the analysis. Based on the theoretical model and considering the items that fell in each construct (taking into consideration factor loading), dimensions were labeled as follows: Factor 1=short-term family-oriented, Factor 2=stewardship family-oriented, Factor 3=long-term family-oriented, Factor 4=short-term business-oriented, Factor 5=stewardship business-oriented, and Factor 6: long-term business-oriented. The naming process was based on current theory considering the items included in each dimension. The family and business orientation was kept in each category because it clearly emerged from the test, but the economic versus non-economic nature was modified by including two references captured by the way items were integrated: (1) temporal perception by considering long-term versus short-term orientation and (2) the focus of attention on a diverse group of stakeholder by considering stewardship family orientation or stewardship business orientation. Fig. 2 shows a visual classification that emerged from the analysis.

Factorial analysis of family business goal items.

| Family-oriented economic goal | Family-oriented non-economic-goal | Business-oriented economic goal | Business-oriented non-economic goal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 Short-term family-oriented goal | Factor 2 Stewardship family-oriented goal | Factor 3 Long-term family-oriented goal | Factor 4 Short-term business-oriented goal | Factor 5 Stewardship business-oriented goal | Factor 6 Long-term business-oriented goal | |

| Cronbach's alpha coefficients | .720 | .864 | .780 | .801 | .730 | .705 |

| Explain variance | 9% | 14% | 9% | 13% | 9% | 7% |

| Items | ||||||

| Money available for family | .625 | |||||

| Quality of life at work | .711 | |||||

| Firm-generated family security | .512 | |||||

| Time to be with family | .642 | |||||

| Family loyalty and support | .677 | |||||

| Family unity | .714 | |||||

| Family interest in the enterprise | .704 | |||||

| Development of children's skills | .795 | |||||

| Generate possibilities for children | .814 | |||||

| Respected name in society | .807 | |||||

| Customer loyalty to family name | .668 | |||||

| Good reputation in the business community | .784 | |||||

| Sales growth | .653 | |||||

| Market share | .585 | |||||

| Net profit | .782 | |||||

| Cash flow | .671 | |||||

| Sales ratio | .754 | |||||

| Return on investment | .627 | |||||

| Adapting to client needs | .635 | |||||

| Staff development | .378 | |||||

| Environmental protection | .479 | |||||

| Customer satisfaction | .769 | |||||

| Service quality | .757 | |||||

| Product development | .834 | |||||

| Market development | .779 | |||||

A visual examination of factor loadings shows that there were three items (i.e., staff development, environmental protection, and firm-generated family security) that did not load on any particular construct/dimension or loaded on at least two factors. These items are potential candidates for elimination because they may cause problems when identifying and differentiating constructs/dimensions from each other. Specifically, they may cause problems with discriminate validity, which measures to what extent a construct is unrelated to another construct. Even with this potential issue, these items were not removed prematurely because of the exploratory nature of this step. To continue with the analysis, items were considered part of a construct based on their factor loading. The latter decision also coincides with the theoretical interpretation of the factor. Staff development and environmental protection were included in Factor 5 because its factorial loading load was slightly higher than the rest of the factors and because these concepts have theoretically been considered as non-economic business items related to external stakeholders. Firm-generated family security was included in Factor 1 because its factorial loading was higher than .50. All the factors had Cronbach's alpha coefficients above .70, which is considered good according to generally accepted standards (Hair et al., 2010).

The above analysis demonstrates the multidimensionality of the family business goal concept. Therefore, Research Statement 1 is empirically supported. I can conclude that economic goals are one aspect of overall family business goals but not the only characteristic. In this sense, these results are in line with previous studies showing that family firms pursue business and family goals as well as economic and non-economic goals (Athanassiou et al., 2002; Chrisman et al., 2012; Lee and Rogoff, 1996; Zellweger et al., 2013) by considering different stakeholders. The empirical test reveals, to a certain degree, a match between the theoretical interpretation of family business goals and empirical dimensions that capture the juxtaposition of family logic and business logic at the aggregate level.

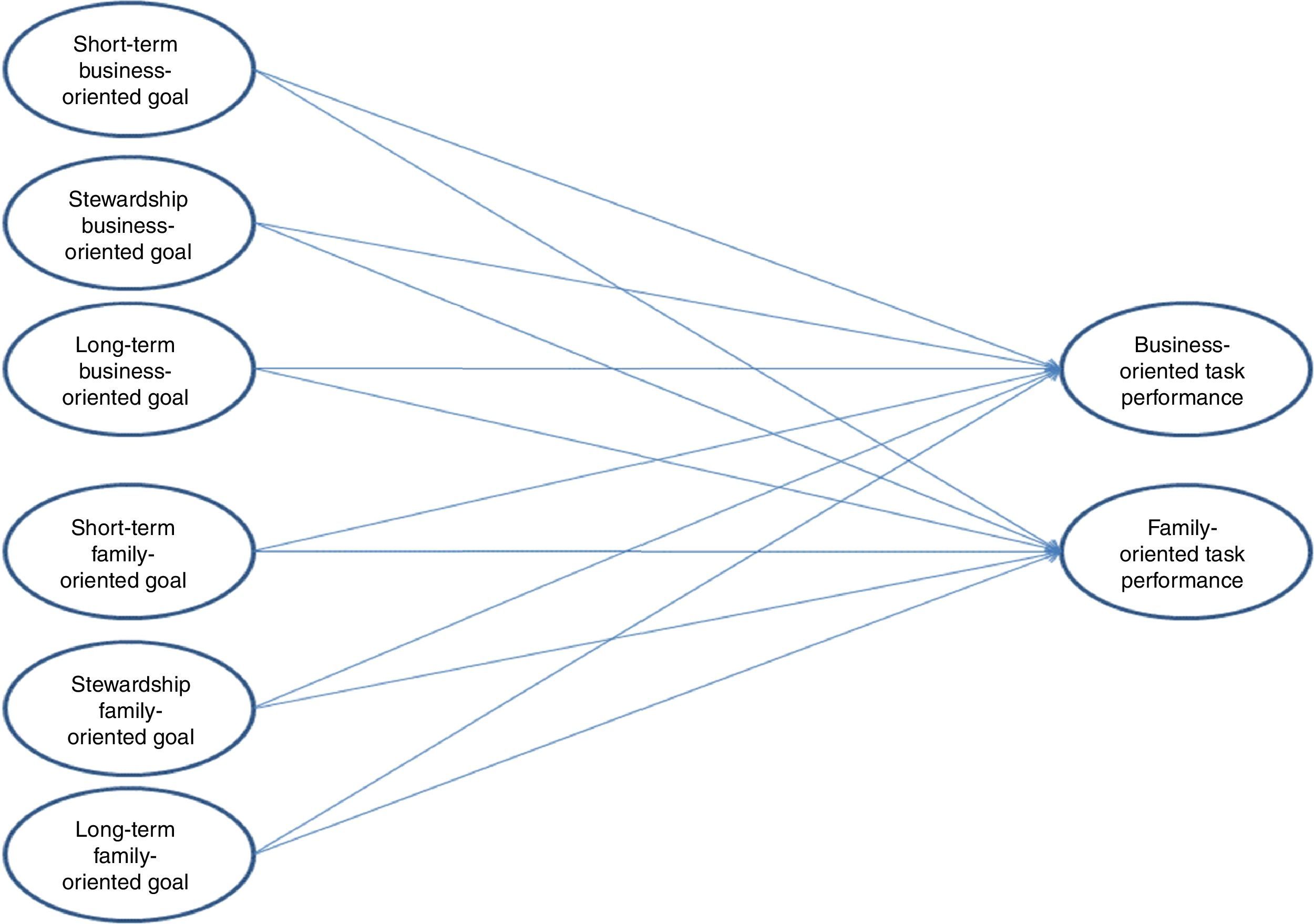

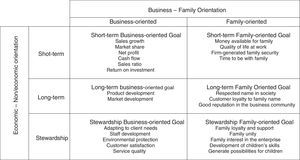

Confirmatory factorial analysisAlthough the above findings are important, the exploratory factorial analysis does not allow us to determine the construct validity of the multidimensional concept of family business goals. In order to validate the concept and its dimensions, I used PLS-SEM. Fig. 3 shows the model under study, which includes all family business goal dimensions as exogenous dimensions (i.e., factors form the exploratory factorial analysis) as well as two new endogenous dimensions. The endogenous dimensions were used to demonstrate the nomological validity of the constructs. The reasoning for these relationships can be traced to the theoretical arguments discussed in the above section—namely, it is expected that goals guide decision making in firms (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011; Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2006). Following this logic, two dimensions were selected at the corporate governance level that capture the family orientation and business orientation of the board of directors (i.e., board task performance). More information about the items used to capture both board task performance dimensions is presented in Appendix A (see Basco and Voordeckers, 2015).

Based on the PLS-SEM technique, the test of the model displayed in Fig. 3 is split into two analyses: a measurement model analysis and a structural model analysis. Both analyses help determine the construct validity of all dimensions of the concept of family business goals. While the measurement model is used to determine reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, the structural model is used to assess nomological validity.

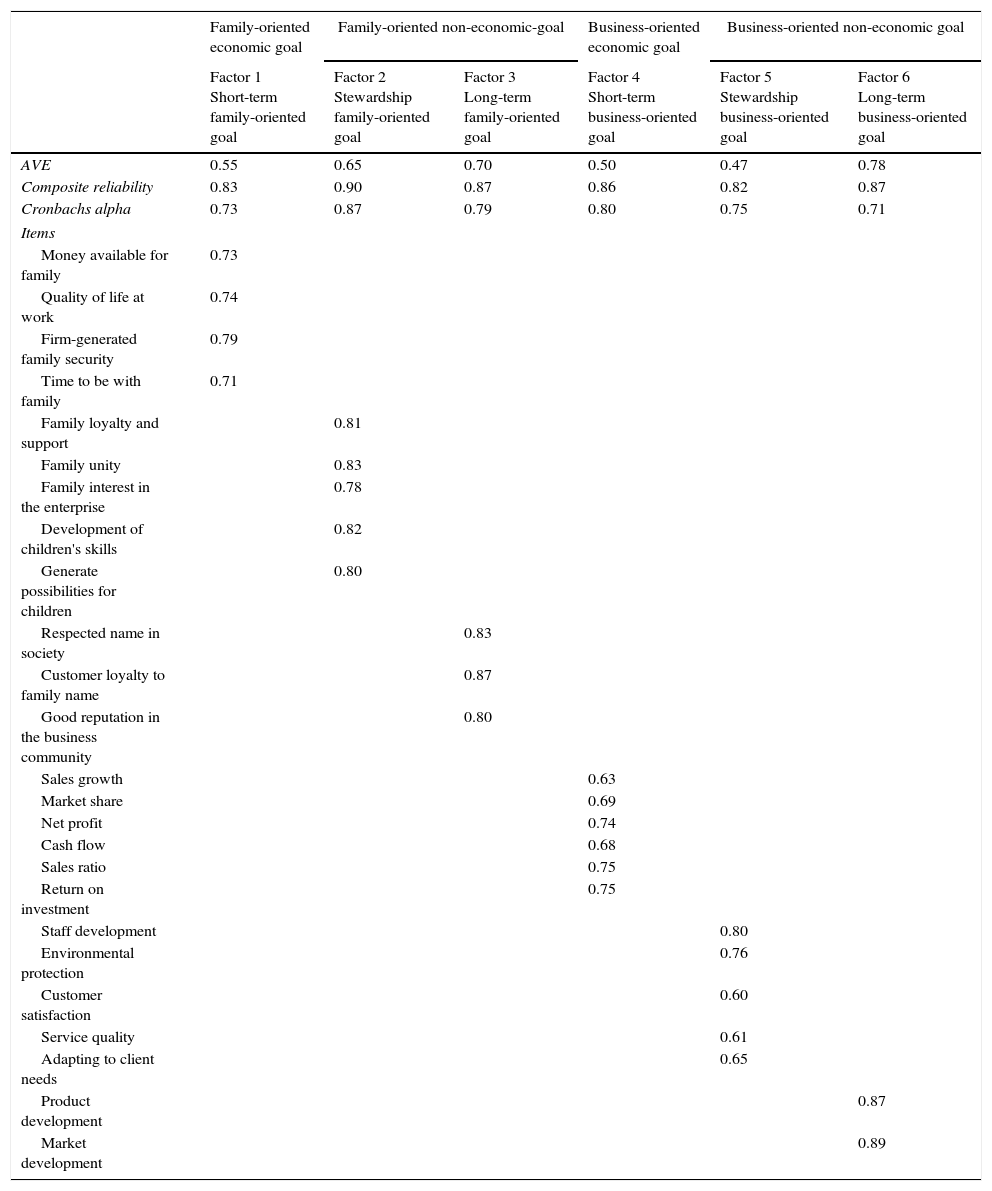

Table 3 shows the main information necessary to assess the construct validity of the proposed constructs. The first analysis consists of assessing reliability, which accounts for item reliability, composite reliability, and average variance extracted (AVE). Item reliability refers to the R2 value associated with each item, with its construct (Hamann et al., 2013) showing the strength between the item and the latent dimension (i.e., construct) (acceptable value should be >.4). All items in the model have an R2 value higher than .4. Regarding composite reliability, which accounts for the reliability and consistency of the measured items representing a latent dimension (Hair et al., 2010), all constructs show composite reliability higher than .60, which is considered an acceptable value. Finally, AVE measures the amount of variance in a set of items that is accounted for through the latent dimension (Fornell and Larcker, 1981) (acceptable value should be >.5). All six dimensions of family business goals have AVE values very close to or higher than .5. With these results, I can conclude that there is enough evidence to support the reliability of the family business goal dimensions.

Results of measurement model.

| Family-oriented economic goal | Family-oriented non-economic-goal | Business-oriented economic goal | Business-oriented non-economic goal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 Short-term family-oriented goal | Factor 2 Stewardship family-oriented goal | Factor 3 Long-term family-oriented goal | Factor 4 Short-term business-oriented goal | Factor 5 Stewardship business-oriented goal | Factor 6 Long-term business-oriented goal | |

| AVE | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.78 |

| Composite reliability | 0.83 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.82 | 0.87 |

| Cronbachs alpha | 0.73 | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.71 |

| Items | ||||||

| Money available for family | 0.73 | |||||

| Quality of life at work | 0.74 | |||||

| Firm-generated family security | 0.79 | |||||

| Time to be with family | 0.71 | |||||

| Family loyalty and support | 0.81 | |||||

| Family unity | 0.83 | |||||

| Family interest in the enterprise | 0.78 | |||||

| Development of children's skills | 0.82 | |||||

| Generate possibilities for children | 0.80 | |||||

| Respected name in society | 0.83 | |||||

| Customer loyalty to family name | 0.87 | |||||

| Good reputation in the business community | 0.80 | |||||

| Sales growth | 0.63 | |||||

| Market share | 0.69 | |||||

| Net profit | 0.74 | |||||

| Cash flow | 0.68 | |||||

| Sales ratio | 0.75 | |||||

| Return on investment | 0.75 | |||||

| Staff development | 0.80 | |||||

| Environmental protection | 0.76 | |||||

| Customer satisfaction | 0.60 | |||||

| Service quality | 0.61 | |||||

| Adapting to client needs | 0.65 | |||||

| Product development | 0.87 | |||||

| Market development | 0.89 | |||||

The second construct validity analysis consists of assessing convergent validity, which refers the extent to which items of a specific construct converge or share a high proportion of variance in common (Hair et al., 2010). The value of standardized factor loadings (acceptable value>.5) and statistical significance are used to assess convergent validity. In the model, all standardized factor loadings are above .50 (see Table 3) and are statistically significant. These results give enough evidence to accept convergent validity for the family business goal dimensions.

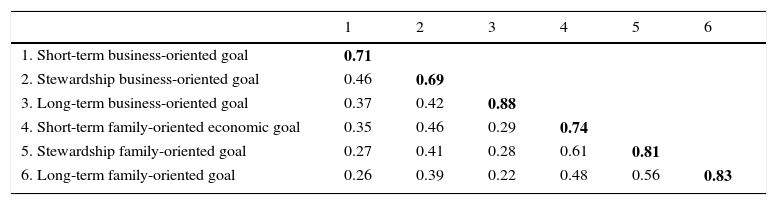

The third step in assessing construct validity is to determine the discriminant validity, which measures to what extent a construct is truly distinct from other constructs (Hair et al., 2010). If the square root of the AVE is greater than all corresponding correlations among dimensions, then one can conclude that there is evidence of discriminate validity. As can be seen in Table 4, the square root of the AVEs is greater than all corresponding correlations.

Discriminant validity of dimensions.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Short-term business-oriented goal | 0.71 | |||||

| 2. Stewardship business-oriented goal | 0.46 | 0.69 | ||||

| 3. Long-term business-oriented goal | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.88 | |||

| 4. Short-term family-oriented economic goal | 0.35 | 0.46 | 0.29 | 0.74 | ||

| 5. Stewardship family-oriented goal | 0.27 | 0.41 | 0.28 | 0.61 | 0.81 | |

| 6. Long-term family-oriented goal | 0.26 | 0.39 | 0.22 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.83 |

Finally, determining nomological validity is the final step in assessing construct validity. Nomological validity refers to determining whether correlations among dimensions (i.e., belonging to the concept) and structural relationships with third dimensions make theoretical sense as well as comparing structural relationships with similar studies that attempt to model similar relationships (Hair et al., 2010; Hamann et al., 2013). The correlations between dimensions in the model are logical from a common-sense perspective. As was expected, the family business goal dimensions are related to each other, but at the same time, the correlations are not big enough to overlap—that is, the constructs do not measure the same unobservable concepts. Moreover, I found that short-term business-oriented and stewardship business-oriented goals are significantly related to business-oriented board task performance, while stewardship family-oriented goal are related to family-oriented board task performance. However, short- and long-term family-oriented goals are not related to the proposed endogenous variables. Because of the exploratory nature of this research, this does not invalidate the nomological validity of the dimensions that form the concept, but these results open new lines of research because it seems that the effects of different family business goal dimensions on decision making are not the same. This forces researchers to theorize on the relationship between goals and decision making by considering the individual relationship as well as the multidimensional relationship.

Content validityIn addition to the aforementioned construct validity, an analysis of content validity is required to provide evidence about the validity of the assessment instrument. Content validity “is the degree to which elements of an assessment instrument are relevant to and representative of the targeted construct for a particular assessment purpose” (Haynes et al., 1995, p. 238). Following Haynes et al.’s (1995) recommendations, I took several steps to guarantee content validity. First, the theoretical part of the article attempted to define the domain and dimensions of the concept as one main requirement to frame the analysis of content validity. Items were collected from an exhaustive literature review, which guaranteed the representation of the items for each dimension. That is, current knowledge guided the process for item selection. Second, the questionnaire was reviewed by academic and family business experts to evaluate consistency and guarantee the ex-ante validation process (Hinkin and Schriesheim, 1989). Third, the questionnaire was then pilot-tested using a small number of family business members who were not resampled in the main study. Finally, to ensure quality, the survey was administered by a professional survey research firm.

Additionally, an ex-post validation procedure was applied in order to analyze whether items represent the domain. There is a high degree of consistency between the theoretical interpretation of the dimensions and the empirical dimensions that emerged from the analysis when considering the underlying structure of the selected items. There is one exception in the dimension named short-term family-oriented goal, which contains four items: money available for the family, firm-generated family security, quality of life at work, and time to be with family. The last two items did not seem to clearly capture the meaning of the dimension. Nevertheless, the final decision was to leave these two items for several reasons. Having two items that are purely economic and short-term oriented, the rest of the items have to be interpreted in similar sense. For instance, quality of life at work has an economic meaning because the more economically solid the firm is, the better the relationship between the family and business systems and the higher the quality of working in the firm are likely to be. In a similar way, when the firm is economically mature and big enough, it will help strengthen the relationships between both systems and increase the time that members share. It looks like participants considered these goals to be related to economic wealth.

Therefore, it is possible to conclude that for this exploratory research, ex-ante and ex-post content validity was satisfactorily achieved by defining the content domain of interest, selecting and developing items that represent the domain, assembling the items into the questionnaire instrument, and relying on “appeals to reason” (Nunnally, 1978, p. 93) to interpret the dimensions.

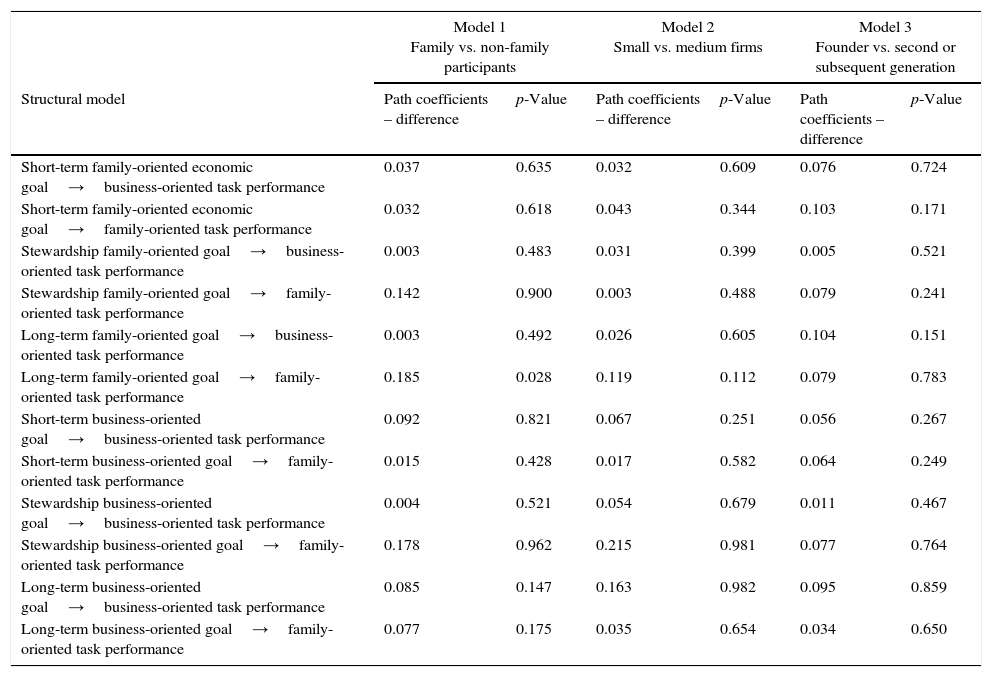

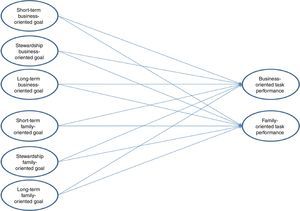

RobustnessAdditional tests were performed to check the consistency of the results. The aim of the robustness tests was to assess the stability of the proposed model in capturing the concept of family business goals. Therefore, the consistency of the model was verified through the use of three control variables: affiliation of respondents, firm size, and generation. For each of these variables, the dataset was split into two groups, and group comparison analyses were performed (PLS-based group comparisons). This approach does not rely on distributional assumptions and produces a bootstrap analysis, which tests group differences. Three multigroup comparison analyses were carried out for each control variable. First, because not all respondent were family members, differences between two groups of participants—family and non-family respondents—were checked. In Model 1 (Tables 5 and 6), of the 25 relationships in the measurement model, only five were different between both groups (see p-values), a marginal number, and the relationships were stronger for the family respondent group. Second, regarding firm size, the sample was divided into two groups: small and medium firms. In Model 2 (Table 6), of the 25 relationships in the measurement model, only five were different between both groups (see p-values), a marginal number, and the relationships were stronger for small firms. Finally, regarding the generation managing the firm, the sample was divided in two groups: founder and second/subsequent generations. In this analysis, only one relationship was significant. Consequently, we can conclude that the proposed model is consistent because the dimensions of the concept of family business goals remain stable within different groups.

Multi-group analysis – structural model.

| Model 1 Family vs. non-family participants | Model 2 Small vs. medium firms | Model 3 Founder vs. second or subsequent generation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural model | Path coefficients – difference | p-Value | Path coefficients – difference | p-Value | Path coefficients – difference | p-Value |

| Short-term family-oriented economic goal→business-oriented task performance | 0.037 | 0.635 | 0.032 | 0.609 | 0.076 | 0.724 |

| Short-term family-oriented economic goal→family-oriented task performance | 0.032 | 0.618 | 0.043 | 0.344 | 0.103 | 0.171 |

| Stewardship family-oriented goal→business-oriented task performance | 0.003 | 0.483 | 0.031 | 0.399 | 0.005 | 0.521 |

| Stewardship family-oriented goal→family-oriented task performance | 0.142 | 0.900 | 0.003 | 0.488 | 0.079 | 0.241 |

| Long-term family-oriented goal→business-oriented task performance | 0.003 | 0.492 | 0.026 | 0.605 | 0.104 | 0.151 |

| Long-term family-oriented goal→family-oriented task performance | 0.185 | 0.028 | 0.119 | 0.112 | 0.079 | 0.783 |

| Short-term business-oriented goal→business-oriented task performance | 0.092 | 0.821 | 0.067 | 0.251 | 0.056 | 0.267 |

| Short-term business-oriented goal→family-oriented task performance | 0.015 | 0.428 | 0.017 | 0.582 | 0.064 | 0.249 |

| Stewardship business-oriented goal→business-oriented task performance | 0.004 | 0.521 | 0.054 | 0.679 | 0.011 | 0.467 |

| Stewardship business-oriented goal→family-oriented task performance | 0.178 | 0.962 | 0.215 | 0.981 | 0.077 | 0.764 |

| Long-term business-oriented goal→business-oriented task performance | 0.085 | 0.147 | 0.163 | 0.982 | 0.095 | 0.859 |

| Long-term business-oriented goal→family-oriented task performance | 0.077 | 0.175 | 0.035 | 0.654 | 0.034 | 0.650 |

Multi-group analysis – measurement model.

| Model 1 Family vs. non-family participants | Model 2 Small vs. medium firms | Model 2 Founder vs. second or subsequent generation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement model | Outer loadings difference | p-Value | Outer loadings difference | p-Value | Outer loadings difference | p-Value |

| Adapting to client needs←stewardship business-oriented goal | 0.012 | 0.542 | 0.009 | 0.416 | 0.007 | 0.476 |

| Cash flow←short-term business-oriented goal | 0.061 | 0.215 | 0.060 | 0.769 | 0.025 | 0.639 |

| Customer loyalty to family name←long-term family-oriented goal | 0.015 | 0.378 | 0.017 | 0.360 | 0.033 | 0.282 |

| Customer satisfaction←stewardship business-oriented goal | 0.001 | 0.503 | 0.196 | 0.037 | 0.046 | 0.654 |

| Development of children's skills←stewardship family-oriented goal | 0.007 | 0.434 | 0.002 | 0.506 | 0.011 | 0.426 |

| Environmental protection←stewardship business-oriented goal | 0.008 | 0.544 | 0.059 | 0.803 | 0.044 | 0.746 |

| Family interest in the enterprise←stewardship family-oriented goal | 0.104 | 0.016 | 0.066 | 0.081 | 0.038 | 0.282 |

| Family loyalty and support←stewardship family-oriented goal | 0.030 | 0.238 | 0.053 | 0.090 | 0.001 | 0.519 |

| Family unity←stewardship family-oriented goal | 0.026 | 0.251 | 0.007 | 0.416 | 0.036 | 0.832 |

| Firm-generated family security←short-term family-oriented goal | 0.025 | 0.653 | 0.080 | 0.905 | 0.038 | 0.737 |

| Generate possibilities for children←stewardship family-oriented goal | 0.058 | 0.879 | 0.091 | 0.037 | 0.076 | 0.154 |

| Good reputation in the business community←long-term family-oriented goal | 0.037 | 0.352 | 0.065 | 0.779 | 0.075 | 0.876 |

| Market development←long-term business-oriented goal | 0.031 | 0.270 | 0.034 | 0.713 | 0.001 | 0.538 |

| Market share←short-term business-oriented goal | 0.054 | 0.785 | 0.005 | 0.518 | 0.000 | 0.512 |

| Money available for family←short-term family-oriented goal | 0.029 | 0.353 | 0.009 | 0.539 | 0.082 | 0.202 |

| Net profit←short-term business-oriented goal | 0.114 | 0.060 | 0.011 | 0.425 | 0.057 | 0.825 |

| Product development←long-term business-oriented goal | 0.010 | 0.550 | 0.076 | 0.085 | 0.034 | 0.288 |

| Quality of life at work←short-term family-oriented goal | 0.000 | 0.505 | 0.051 | 0.252 | 0.111 | 0.921 |

| Respected name in society←long-term family-oriented goal | 0.172 | 0.006 | 0.028 | 0.670 | 0.102 | 0.960 |

| Return on investment←short-term business-oriented goal | 0.126 | 0.008 | 0.048 | 0.813 | 0.100 | 0.087 |

| Sales growth←short-term business-oriented goal | 0.001 | 0.499 | 0.060 | 0.751 | 0.049 | 0.328 |

| Sales ratio←short-term business-oriented | 0.002 | 0.527 | 0.065 | 0.143 | 0.080 | 0.167 |

| Service quality←stewardship business-oriented goal | 0.195 | 0.032 | 0.131 | 0.107 | 0.050 | 0.674 |

| Staff development←stewardship business-oriented goal | 0.067 | 0.869 | 0.003 | 0.491 | 0.022 | 0.359 |

| Time to be with family←short-term family-oriented goal | 0.044 | 0.285 | 0.069 | 0.183 | 0.101 | 0.177 |

The motivation of this investigation was grounded in the fact that the borrowed-research strategy (i.e., the application of theories, measures, and constructs from mainstream fields to family business samples) that has been used extensively in the family business field (Pérez Rodríguez and Basco, 2011) has limitations in explaining the specific behavior of family firms. Even though most research has shown differences between family and non-family firms and among different types of family firms, almost all current studies have theoretically assumed that these differences are produced by family effects on firm goals and priorities. Without measuring what specifically causes differences in firm behavior, family business research—specifically the family business theorizing process—is floating in the midst of assumptions used to justify observational descriptive data. This has happened because despite these assumptions, family business goals have hardly been viewed using an integrated framework to conceptualize the concept or empirically test it.

To address this problem—that is, to move research beyond the presumption level—this article argued that it is necessary to better understand the concept of family business goals. More specifically, it was proposed that family business goal concept has to address two issues: (1) the dimensionality of family business goals, which is about the nature of the concept itself, and (2) the operationalization of the concept of family business goals, which is about the selection and combination of measures (i.e., items) and methods to make the concept operative. To deal with these aims, an exploratory step-by-step methodology was developed by combining both a theoretical approach and an empirical approach. With this methodology, the concept was defined, the data were explored, and the theoretical representations through empirical data were tested.

In the first methodological step, based on an inductive theoretical interpretation of family business goals, I theorized that family business goals are formed based on the nature of economic and non-economic goals combined with specific orientations—namely, family and business orientations—because of the juxtaposition of family logic and business logic. This led to family business goals being considered as a multidimensional concept. In the second methodological step, which was based on an inductive empirical approach, the proposed multidimensional concept of family business goals was operationalized. The concept of family business goals was empirically tested, and evidence of the concept's multidisciplinary nature was found. Therefore, this article concludes that family business goals are not a one-dimensional construct nor are they likely to be described with one simple item (i.e., measure).

This article extends the current line of research related to family business goals in two different ways. First, even though several studies have highlighted the importance of different family firms by defining lists of potential family business goals (e.g., Dunn, 1995; Lee and Rogoff, 1996; Tagiuri and Davis, 1992; Westhead and Howorth, 2007) or capturing partial aspects of the concept (e.g., Kim and Gao, 2013; Zellweger et al., 2013), this article adds new light by attempting to capture the underlying structure of the plethora of family business goals. Consequently, this study provides a certain order to interpret the multidimensional aspects of family business goals and to address the recent call made by Priem and Alfano (2016). Second, this study extends previous research, which shows that family members—based on their own objectives and their own positions in the family and in the business—can alter family business goals (Kotlar and De Massis, 2013), by exhaustively identifying the general goals that can emerge from the bargaining process.

Theoretical and practical implicationsThis research makes several contributions to the academic and practical spheres. Regarding academic contributions, this article has theoretical and methodological implications. First, this research addressed the call made by Miller and Le Breton-Miller (2014) about the current limitation in family business research of putting family firms’ multiple priorities under the same umbrella of socioemotional wealth. In this sense, this article contributes to the family business theory-building process because it theorizes about the dimensionality of family business goals by re-assembling fragmented knowledge about goals and conceptualizing it based on the nature of the possible stakeholders for whom the goals are important and on the family-firm context in which the goals are decided upon. Therefore, recognizing the nature of family business goals, this research opens new doors to move family business research forward. One important future research path is to ask why the proposed dimensionality emerges—that is, to better explore the antecedents of different family business goal dimensions as Zellweger et al. (2013) recently did theoretically using identity theory. For instance, in the proposed model, the family's concern for organizational reputation may be related to long-term family-oriented and stewardship business-oriented goals.

Second, this research attempts to address the need for the family business field to make operative concepts by assuring the measurement accuracy of its constructs/dimensions (Pearson and Lumpkin, 2011), specifically the need to find multifaceted and fine-grained measures for family firm priorities (Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2014). Even though researchers have recognized that different goals exist in family firms, there have been no empirical attempts to dismantle the underlying structure of family business goals. Empirically, this study selected and combined a set of measures and defined specific methods to validate the concept of family business goals. Consequently, the scheme for understanding and analyzing family business goals may serve as a reference frame for future research to reduce the current diffusion regarding the interpretation and operationalization of family business goals (e.g., Chrisman et al., 2012; Kim and Gao, 2013). The conclusion that can be drawn from this article is that not all goals are the same, nor do they have the same meaning. Even more, not all family-oriented goals can be grouped in the same category.

Finally, it is expected that the contributions from this article will theoretically and empirically materialize to answer the question of what makes family firms behave differently by addressing the suggestion made by Carney et al. (2015) that studying family firm behavior (e.g., strategic choice) and firm performance requires researchers to analyze firms’ economic and non-economic preferences. So far, researchers have recognized differences in firm behavior without clearly understanding what causes these differences, or they have assumed that different goals may act as driving forces but have not measured them explicitly (with some exceptions; see Chrisman et al., 2013). In this sense, this research sheds some light by identifying different aspects (i.e., dimensions) of family business goals that can affect management and government decision making and strategic posture. Future studies should address these relationships theoretically and empirically. Moreover, the concept of family business goals can also be connected to firm performance. In this sense, this article may explain the firm performance typology proposed by Zellweger and Nason (2008). That is, the overlapping, causal, synergetic, and substitutional characteristics of firm performance are based on family business goals and their effects on firm behavior as a condition to achieve different firm-performance targets. Family business goals could be considered a new research paradigm in the family business field, which may help clarify why differences in family business behavior happen.

This research also has practical implications for family owners, family members working in the firm, practitioners, and non-family minority investors in family firms. Specifically, this research provides a framework to understand the constellation of family business goals moving across different scales. Understanding and measuring goals in a holistic way is essential in allowing stakeholders not only to evaluate firms’ progress and evolution while contemplating diverse stakeholder needs and the family-business context but also to interpret and discern past and future competitive actions.

Limitations and future research linesAside from the abovementioned implications, this study has several limitations, which not only represent the boundaries for its contributions but also provide opportunities for future research aimed at extending knowledge about family business goals.

Even though this research represents a step forward in the effort to conceptualize and operationalize family business goals, how to incorporate family business goals into a family business theory is still puzzling. Future empirical studies have to incorporate family business goals as independent dimensions that precede behavioral dimensions and firm performance following the research line of Miller and Le Breton-Miller (2006) and Gomez-Mejia et al. (2011). Such research efforts may shed some light on questions regarding why family firms behave differently than non-family firms and, even more, why there are behavioral differences among different types of family firms. However, due to the dimensionality of family business goals, it could be necessary to theorize on and empirically prove how dimensions of family business goals affect different aspects of family business behavior—that is, not all dimensions will have the same influence on management and governance decision making. Also, of course, the study of family business goals should be integrated with the concept of family business performance since there is an intrinsic relationship between goals and performance. In this sense, the current concept of family business goals could be combined with the theoretical model of firm performance developed by Zellweger and Nason (2008). These authors posited that the dimensionality of firm performance (based on economic and non-economic aspects) could create different types of relationships among dimensions of firm performance (e.g., overlapping, causal, synergistic, substitutional relationships). However, based on the theoretical proposal, such relationships may be rooted in goals because goals affect behavior, which leads firms to achieve different dimensions of firm performance with varying intensity.

The second limitation of the proposed model is that it does not incorporate the time dimension into the analysis. However, there is a long tradition in family business research suggesting that time could be an important dimension because family members (e.g., different generations) participate differently in family firms, which may alter family business goal dimensions (i.e., Basco and Calabrò, 2015). It could be very useful to recognize and understand how different dimensions of the family business goal concept change over time, specifically by considering the number of family generations involved in the firm. This is an important distinction because even though time and generation could be highly correlated, the strategies families use to deal with the transmission of ownership and management may affect goals. That is, even as time passes, a prune ownership strategy could maintain the family business within a close circle and reduce the number of family members involved, thereby decreasing agency problems (owner-owner) and maintaining some specific family business goals no matter the generation in charge.

Third, based on the inductive theoretical approach, the conceptual model of family business goals is non-contextual, while the inductive empirical approach is focused on a specific context (i.e., Spain). Future studies should replicate this research in different environments. Such a research strategy would bolster the family business theorizing process in two different ways. First, new theoretical and empirical studies extending the current research line would help achieve consensus for a theory of family business goals by supporting or discrediting it (Tsang and Kwan, 1999). Second, using different contexts to replicate this research may help contextualize the concept of family business goals (Whetten, 2009). Beyond this, it could be possible to develop a theory of the context (Whetten, 2009) related to family business goals—namely, to understand how the context could affect dimensions of family business goals. Fourth, the family business goal scale used in this study was adapted from existing research. However, alternative methods can be used to improve the scale, for instance, the Delphi method or hybrid Delphi method (Landeta et al., 2011). The Delphi method is a group of techniques that can be used to form a single opinion from a group of individuals (Rowe and Wright, 1999; Sniezek, 1990). Therefore, this method could be used to validate and refine the current scale.

Finally, future research should investigate microprocesses that exist at the intersection of family, firm, and society logics that create some specific balance within family business goals. That is, future research should address the question of what mechanisms are responsible for the family business goal dimensions. Moreover, future studies should consider the points of view of other important stakeholders in order to capture the various nuances of family business goals. Research using more than one informant could help create a better picture of family business goals by confirming the dimensions of the concept discovered in this article in more than one group of similar stakeholders and by identifying the relative importance of these dimensions in each group of stakeholders. Additionally, this line of research may assist in detecting variations in the dimensions of the family business goal concept for different stakeholders, which may be a promising line of research for better understanding the antecedents of family business behavior when several stakeholders with different balances of these goal dimensions intervene in the firm.

Differences between family and non-family firms and have been demonstrated, for instance, in relation to innovation (Block et al., 2013; Classen et al., 2014), open innovation search strategies (Classen et al., 2012), entrepreneurial orientation (Boling et al., 2015), reputation (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz, 2013), environmental performance (Dekker and Hasso, 2014), and corporate misconduct (Ding and Wu, 2014), among other management and government decision making. Even more, because family firms are not a homogenous group, differences have been observed among types of family firms. More specifically, different degrees of family involvement in ownership, governance, and management affect firm behavior, for instance, regarding internationalization (Mazzola et al., 2013), strategic behaviors (Basco, 2014), and family leadership (D. Miller et al., 2013b).

I conducted an exhaustive review of ownership, board of directors, and management composition based on name and surname. The system of surnames in Spain makes it possible to identify family relationships because women never take their husband's surname, whereas children take both their father's and mother's surnames.