The financial crisis that started in the USA in 2007 has obliged many small financial entities in southern Europe to undertake mergers in order to comply with the stability and solvency policies established by the European Central Bank. In Spain, this situation has led to a profound restructuring of the financial system, obliging many of these institutions to decide whether or not to maintain their regional brand identity after such a merger. The purpose of this study was twofold: on the one hand, to analyze the importance customers attach to the origin of their usual financial institution and the relative utility they give to the three levels of brand origin presented: regional, national and foreign, and, on the other, to assess whether consumers’ level of ethnocentrism modifies their preference structure and, if so, to identify the profile of the individuals composing each segment. The technique of Conjoint Analysis was applied to a survey of 427 customers. The results showed the bank's to be the attribute with the greater importance in forming customers’ preferences than other characteristics of the institution such as the treatment by employees, the location of offices, the electronic banking services, and the number of social activities the entity carries out in the region. In addition, the respondents prefer regional brand origin over national and foreign. Both the importance and the utility attached to the regional brand origin increase with higher levels of consumer ethnocentrism. The findings of this study will serve to these entities as a guide for their decision-making regarding brand management.

Research on the use of products’ place of origin as a differentiation strategy has gained prominence in the field of marketing with the growth of the globalization and internationalization of markets. The place-of-origin (PO) effect is defined as “a set of strengths and weaknesses related to the place-of-origin that incorporates or subtracts the value supplied by a brand or service to the manufacturer and/or its clients” (Papadopoulos and Heslop, 2003). Although it is now a research topic in a period of maturity (Ahmed and d’Astous, 2008), there have been a steadily increasing number of studies devoted to it. In recent years, authors like Samiee et al. (2005), Usunier (2011) and Usunier and Cestre (2008) have questioned its importance in international marketing research. However, other authors argue for its relevance, affirming that PO continues to generate interest among scholars (Pharr, 2005; Herz and Diamantopoulos, 2013), and that there still remain issues to be investigated in greater depth (Jaffe and Nebenzahl, 2001; Papadopoulos and Heslop, 2003).

Among the main suggestions about the topics that research on origin should address are the need to focus on Brand Origin (BO) rather than Country-of-Origin (CO) (Samiee, 2011; Usunier, 2011), and the need for a better understanding of various CO dimensions and their influence on consumer behaviour (Kim and Park, 2010). The literature review carried out for this study allowed us to identify another gap in research, specifically, the analysis of the PO effect in different levels simultaneously, not only at CO level. In today's globalized market, a great number of products of different origins are available to consumers. In this context, PO could be evaluated in three levels: regional, national and foreign, all of which coexisting at the same time in the same markets.

Most studies have up to now focused on analysing the CO effect and its explanatory variables. For example, one can cite as recent studies in this area those of Godey et al. (2012), Claret et al. (2012), Lee et al. (2013), and Lagerkvist et al. (2014). There are also many studies with a regional focus, with the main reference being that of Van Ittersum et al. (2003) on potatoes and beer in regions of the Netherlands. Indirectly involving this effect, one might also mention agribusiness marketing work that has analyzed the valuations and preferences of consumers for the “protected denominations of origin” specific to certain regions (e.g., Hersleth et al., 2012; Caldas and Rebelo, 2013; Chamorro et al., 2015).

Nevertheless, very few works have combined the analysis of CO and Region-of-Origin (RO) simultaneously. While RO is a part of CO, it has special connotations, since regions are much more homogeneous in terms of human and natural factors than countries. Regional branding thus allows then the possibility of differentiating a product from both foreign and domestic competition (Bruwer and Johnson, 2010), especially in countries in which regions are highly heterogeneous.

Our literature review also highlighted a fourth gap in research: the RO effect in the services sector. Studies on PO have focused on industrial products (e.g., Ahmed and d’Astous, 1995; Edwards et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2011), and even more so on consumer goods (Gázquez et al., 2012; Claret et al., 2012; Lagerkvist et al., 2014). There are also studies that have combined PO with services, but all with a CO level focus, setting aside the RO level. Examples are: Kraft and Chung (1992) on B2B export assistance; Shaffer and O’Hara (1995) on legal services; Lascu and Giese (1995), Pecotich et al. (1996), Chaney and Gamble (2008) on retail services; Harrison-Walker (1995) on ophthalmology services; Bruning (1997) on airline preferences; Ahmed et al. (2002) on cruise lines; Bigné and Sánchez (2002) on banks; Lin and Chen (2006) on insurance and catering; Roggeveen et al. (2007) on call service centres; Ferguson et al. (2008) on higher education services; and Gazley et al. (2011) on motion pictures.

The present study addresses three of those gaps: the emphasis on brand origin, RO in the services sector, and the study of different levels of brand origin simultaneously. Also, the role played by consumers’ level of ethnocentrism is analyzed via a descriptive analysis. Specifically, the overall aim of the present study was therefore to analyze the preference structure of customers in choosing their usual financial institution. This allowed us, on the one hand, to assess the importance they assign to its origin and what level of brand origin gives them greater utility, and, on the other, to determine whether customers with different levels of ethnocentrism also have different preferences and, if so, to identify what is the profile of individuals within each customer segment.

To the best of our knowledge, the only previous studies on the origin effect that have considered the banking sector are those of Bigné and Sánchez (2002) and Tumpal (2014). Bigné and Sánchez (2002) found that the consumers of four countries showed a preference for their own country's banks as against foreign banks. Tumpal (2014) analyzed the importance that consumers give to three different aspects of a bank's origin: brand origin, headquarters location and employees nationality. There are other studies that have analyzed the selection criteria for financial entities, but they did not include the brand origin.

In terms of managerial implications, the motivation for this work is the great potential value in the present context of the transfer of the results to the Spanish financial sector. The financial crisis that began in the USA in 2007 with so-called “subprime” mortgages spread to the entire international financial system. It hit particularly hard at southern Europe's financial sector, obliging many small financial entities to undertake mergers in order to comply with the stability and solvency policies established by the European Central Bank.

Indeed, in the case of Spain, the number of financial institutions has been steadily falling. By 2012, the financial system consisted of 277 companies, of which 28.5% were national banks, 31.4% were divisions of foreign banks, and the remaining 40% were entities of the so-called Social Economy, i.e., savings banks and credit unions, which are typically very small in size and have a geographical scope primarily focused on one region of the country.

The restructuring in the Spanish financial sector has mainly affected this third type of institution, savings banks and credit unions, both of which are closely linked to their region-of-origin, and have fewer possibilities for reorganizing their accounts because their legal status limits their capacity to raise capital. In this situation, some institutions have chosen to undertake mergers that have resulted in a new entity, which, in most cases, has lost its link to any particular region. Others, however, have chosen to create the so-called “Institutional Protection Systems” (SIP's in the Spanish acronym). In this case, all the entities that become part of the integration process maintain their legal form, and can therefore either also maintain their regional identity branding or together use a new single brand for the national market.

Consequently, behind the economic and financial decision to integrate with erstwhile competitors, there exists, albeit implicitly, a marketing decision that has to be made: to maintain the brands of origin or to allow them to be lost. The present investigation aims to provide a response to this dilemma, and for its results to serve as useful guidelines for managers of financial institutions with regard to the management of the linkage of their brands with their origin. The population studied was that of financial institutions and their customers in the Region of Extremadura, located in the south-west of the Iberian Peninsula.

The paper is organized as follows. The next section presents the conceptual framework of the place-of-origin effect, then the following sections explain the design and objectives of the research, give the results of the survey, and end with the key findings and implications of the study.

Conceptual frameworkFrom the analysis of the main works devoted to the PO effect, a number of conclusions can be drawn:

- •

There is evidence of the effect on consumers’ perceptions of product quality and reliability.

- •

The effect attenuates as one considers more advanced phases of the purchase decision, being greater for perceptions and attitudes than for purchase intentions.

- •

The effect is not universal, but varies from one product category to another.

- •

The effect is greater when only information about the product's country-of-origin is presented (single-attribute studies) than in multi-attribute studies.

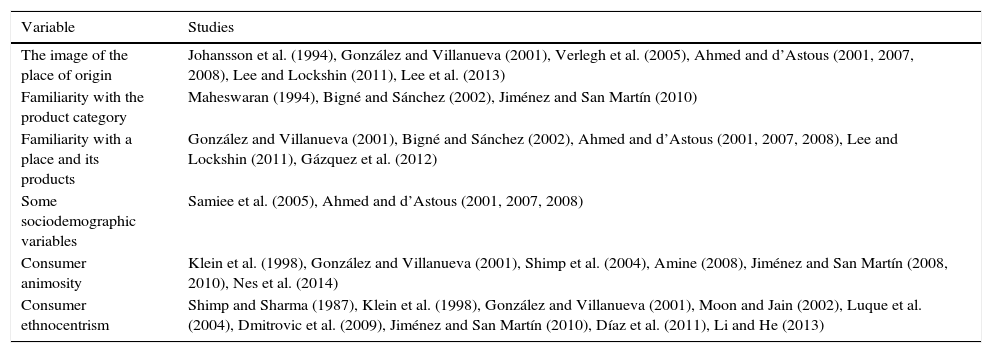

The general conclusion in the literature is that the place of origin does indeed influence the consumer in their perceptions of product quality (Ahmed and d’Astous, 2007; Verlegh et al., 2005; Veale and Quester, 2009), in their preferences (Van Ittersum et al., 2003; Font et al., 2011), or in their purchase intentions (González and Villanueva, 2001; Auger et al., 2010; Godey et al., 2012). The main explanatory variables of the place-of-origin effect that have been discussed in the literature are presented in Table 1.

Main explanatory variables of the place-of-origin effect discussed in the literature.

The product place-of-origin effect is influenced by a number of emotional and normative variables belonging to the disciplines of psychology and sociology, such as consumer animosity and consumer ethnocentrism (Jiménez and San Martín, 2008). Consumer ethnocentrism can be defined as “the belief that a product of one's own ethnic or cultural group is inherently superior to similar products from other cultural or ethnic groups” (Myers, 1995).

The first work devoted to this topic in the field of marketing appeared in the late 1980s (Shimp and Sharma, 1987). Those authors used the term “consumer ethnocentrism” to represent the beliefs that American consumers hold about the appropriateness, or even morality, of buying foreign goods. From the perspective of the most ethnocentric consumers, it is wrong to purchase imported goods because they feel it hurts the domestic economy, causes a loss of jobs, and is simply unpatriotic. For non-ethnocentric consumers, however, foreign products are to be evaluated on their own merits, without considering where they were made.

In a similar vein, the studies of Klein et al. (1998), González and Villanueva (2001), and Moon and Jain (2002) show an inverse relationship of level of ethnocentrism with purchasing behaviour towards foreign products. Other studies (Luque et al., 2004; Dmitrovic et al., 2009) have confirmed that the relationship is direct and positive with respect to purchasing behaviour towards local products. These findings are complemented by those of other studies such as Díaz et al. (2011), which show that, in the absence of high levels of ethnocentrism in a society, individuals’ valuations of products of different origins are more objective, with their giving a relatively low weight to the origin attribute in forming their preferences, and even preferring foreign over local products.

One of the most significant works in identifying a profile of an ethnocentric consumer is that of Sharma et al. (1995). The conclusions they drew about the relationship of this variable with a set of socio-psychological and demographic variables were:

- •

There is a negative relationship between consumer ethnocentrism and openness to other cultures.

- •

There is a positive relationship between consumer ethnocentrism and patriotism.

- •

There is a positive relationship between consumer ethnocentrism and conservatism.

- •

There is a positive relationship between consumer ethnocentrism and the collectivism of the society in which they live.

- •

Women show greater ethnocentric tendencies than men.

- •

There is a negative relationship between consumer ethnocentrism and educational level.

- •

There is a negative relationship between consumer ethnocentrism and income.

Those scholars also demonstrated that the relationships between consumers’ ethnocentrism and attitudes towards imported products are moderated by their perception of both a need for the imported product and the threat of foreign competition. In particular, the effect of consumers’ ethnocentrism on their attitudes should be greater in the case of products that are perceived as being unnecessary or a threat to the individual or domestic economy.

Jiménez and San Martín (2008) show that consumers’ animosity towards a country increases their ethnocentric tendencies, so that such animosity could be regarded as an antecedent of ethnocentrism. Such animosity is defined as: “The remnants of antipathy to a country related to previous or continuing events of a military, political, or economic nature, and which will be reflected in the purchasing behaviour of consumers in international markets” (Klein et al., 1998).

Watson and Wright (2000) state that the profile of the most ethnocentric consumers responds primarily to women consumers who are older, with lower education and income levels than consumers who show little ethnocentrism. Del Río et al. (2003) find that age, education level, concern about the economic situation, and patriotism influence ethnocentric tendencies. Luque et al. (2004) also identify certain antecedents of ethnocentrism, finding that women, older consumers, the less educated, those of higher professional levels, those working in the private sector, the unemployed, and those employed in housework showed more pronounced ethnocentric tendencies.

Objectives and hypotheses developmentAs was noted in the introduction, the objective of this study was to analyze the preference structure of customers so as to determine which criteria or attributes they consider in choosing their usual financial institution, with the brand origin being presented in three levels: regional, national and foreign. This overall aim was formalized as three specific objectives: firstly, to try to determine the relative importance customers attach to the origin of the financial institution with respect to others of its characteristics (the treatment by employees, location of offices, social investment activities, and electronic banking services); secondly, to determine the estimated utilities of each of a financial institution's options for its origin branding – regional, national, or foreign; and thirdly, to determine whether this preference structure is modified by the customer's level of ethnocentrism and, if so, to identify the profile of individuals within each customer segment.

Prior to the design of a final questionnaire with which to collect data for the study, we proceeded to select the attributes to consider. This selection was based on a literature review of the selection criteria used by financial entities’ clients. As Sayani and Miniaoui (2013) observe, many studies have been performed on the process of selecting a bank in many countries around the world, but, as mentioned above, to the best of our knowledge none of them have taken the origin attribute into account. For example, Martenson (1985) studied 558 bank customers in Sweden and found that bank location, availability of loans, and payment of salary through a certain bank were reasons for the choice. Laroche et al. (1986) analyzed a sample of 400 individuals in Montreal. They found that location convenience, speed of service, and factors relating to the competence and friendliness of bank personnel were considered to be the most important factors. Denton and Chan (1991), in a study carried out in Hong Kong, found the professionalism and friendliness of bank personnel, convenience, and risk (social and financial) reduction to be the primary reasons for using multiple banks. Kaynak et al. (1991) found that frequent banking customers in Turkey preferred friendly bank employees, convenient location of bank branches, fast and efficient service, availability of credit and financial services advice. Kaynak and Kucukemiroglu (1992) studied the importance of selected patronage factors in choosing domestic and/or foreign banks in Hong Kong, and the customers’ perceived usefulness of various banking services. They found fast and efficient service, the friendliness of bank personnel, and convenience to be important motives for the choices made.

More recently, Al Mossawi (2001) studied the banking preferences of university students in Bahrain. The results showed that reputation, friendliness of staff and some factors related to convenience to be significant determinants of that population's bank selection. Lee and Marlowe (2003) analyzed how US families choose a financial institution for their checking accounts. They found convenience to be one of the most important decision-making criteria together with retail fees, range of services offered and, personal relationships. In a study of Swedish students using the Conjoint Analysis technique, Mankila (2004) found that the distribution channel was the attribute with the greatest importance for these clients, with the level of Internet banking having the highest utility. They also found that students preferred their current bank to any other major bank. Kaynak and Harcar (2005) studied the bank selection criteria differences between customers of local and of national US banks. They found that lower service charges on checking accounts, lower interest charges on loans, promptness in correcting errors, accurate billing, courtesy of personnel and higher interest payments on saving accounts were more important for national bank customers, whereas fast and efficient service, available parking space nearby, the bank's external appearance, mass media advertising, and interior comfort were mentioned as the most salient factors for local bank customers. Devlin and Gerrard (2005), in a study throughout Britain, found that closeness to home, a family relationship, the recommendation of others, closeness to the workplace dominated the bank selection criteria. Blankson et al. (2009) carried out exploratory research on students’ selection of retail banks in the United States and Ghana. The objective was to establish if there were any significant differences and/or similarities for students from a developed and from a developing economy. The results identified four key factors – convenience, competence, recommendation by parents, and free banking and/or no bank charges – to be consistent across the two economies, although there were also some factors that were not shared between the two countries.

Based on the attributes identified as important from this literature review about bank selection criteria, we made a brief survey of 40 financial institution clients, using both open and closed questions to inquire into which aspects they valued when choosing their institution. Then, with one exception, we chose for the final study the attributes these 40 respondents valued most highly: brand origin, the treatment by employees, the location of the offices, the online services offered, and the social activities that the entity conducts in the respondent's region (defined as sponsorship and promotion of sporting or cultural events, support for the disabled, support for business projects, etc.). The single exception corresponded to the financial conditions that the entity offered. In the questionnaire, it was specified that the decision for one or another financial institution should be based on equal financial conditions. This was to obviate the loss of invaluable information on other variables that would have been hidden by this clearly determinant attribute. In particular, accepting that the financial conditions are a key factor when choosing any entity, we wished to find answers to such questions as: Is it important for the customer that the entity belongs to their region? Should a regional financial institution maintain its brand and reinforce its communication in this regard?

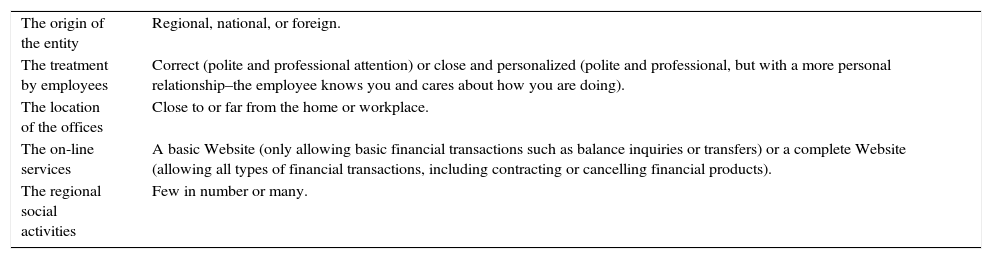

Once the attributes had been selected, the next step was to choose the levels each of them would be divided into (Table 2).

Description of the attributes.

| The origin of the entity | Regional, national, or foreign. |

| The treatment by employees | Correct (polite and professional attention) or close and personalized (polite and professional, but with a more personal relationship–the employee knows you and cares about how you are doing). |

| The location of the offices | Close to or far from the home or workplace. |

| The on-line services | A basic Website (only allowing basic financial transactions such as balance inquiries or transfers) or a complete Website (allowing all types of financial transactions, including contracting or cancelling financial products). |

| The regional social activities | Few in number or many. |

We formed our working hypotheses with respect to the first two objectives on the basis of the literature review on bank the selection criteria and the results of the pilot survey described above, also guided by the findings of some previous studies in other sectors. For instance, Ahmed and d’Astous (1996, 1999) describe CO cues as being more important than brand for customers’ perception of the purchase value and perceived quality of different products. In the same line, Martínez-Carrasco et al. (2006) and Monjardino and Ventura (2001) find that Spanish and Portuguese consumers attach more importance to the origin of agri-food products than to their other attributes, in some cases including price. Although the aforementioned work of Martínez-Carrasco et al. (2006) is an exception, most studies on origin in Spain find consumers to prefer regional over national or international products (Bernabéu and Tendero, 2005; Gil and Sánchez, 1997) or to prefer their region's appellations-of-origin (Fotopoulos and Krystallis, 2003; Tendero and Bernabéu, 2005; Chocarro et al., 2009; Font et al., 2011; Claret et al., 2012; Realini et al., 2013). The aforecited study of Bigné and Sánchez (2002) on banks only reported a preference for domestic versus international entities, since it did not contemplate the RO effect. Furthermore, Javalgi et al. (2001), in a literature review, concluded that the results of studies on CO in services appeared to be similar overall to those for products. Consumers preferred services from their own country, the more economically developed country, or the country with a closer cultural distance. If the results of the studies in services follow the pattern of those for products, then customers would prefer regional over national or foreign services, as it is documented for consumer goods.

Given this context, we posited the following two hypotheses:H1 The origin of the financial institution is an attribute that has a greater importance in the formation of customer preferences than other attributes directly related to the service they are provided, namely, the treatment by employees, location of offices, social investment activities, and electronic banking services. A regional origin of the financial institution will be preferred to a national or foreign origin.

The third objective was to determine whether customer segments with different levels of ethnocentrism have different preference structures, and, if so, to describe the profiles of the individuals composing each segment. As was mentioned in the previous section, research since the late 1980s has provided solid insight into the connection between consumers’ ethnocentricity and their purchasing behaviour. One example was that most ethnocentric American consumers felt buying imported goods was wrong because it could lead to job losses and was unpatriotic, whereas their non-ethnocentric compatriots would judge overseas products simply on their own merits (Shimp and Sharma, 1987). Another was the less ethnocentric the consumer, the more inclined they would be to buy foreign products (Klein et al., 1998; González and Villanueva, 2001; Moon and Jain, 2002), with consumers in very non-ethnocentric societies even giving preference to foreign over local products (Díaz et al., 2011). This direct, positive relationship between ethnocentrism and consumers’ purchasing attitudes in favour of local products relationship finds further confirmation in the work of Luque et al. (2004) and Dmitrovic et al. (2009). On the basis of these findings, we posited two additional hypotheses:H3 The relative importance of the region-of-origin attribute increases with the individual's increasing level of ethnocentrism. Individuals’ estimated utility for a regional financial institution is greater the greater is their level of ethnocentrism.

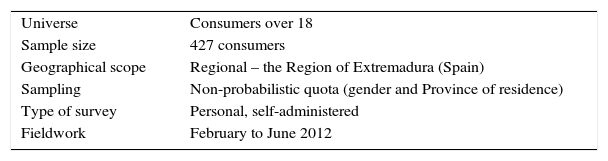

The methodological approach taken was to apply the technique of Conjoint Analysis to the responses in a survey of 427 financial institution clients resident in the region of Extremadura (Table 3). In compositional methods such as that of our pilot survey, direct questions are put in order to evaluate each attribute's relevance. Conjoint analysis, however, uses a decompositional method to determine the customers’ preference structure. In particular, it comprises a set of market research techniques that together measure the value that the market places on each feature of the product, and predicts the value of any combination of features. In essence, it is all about features and trade-offs. The researcher simulates a real market by presenting the consumer with a set of different financial entities to evaluate. By analysing the preferences they express, one can evaluate the importance they attach to the different attributes of those entities, and the utilities they give to the various levels of each attribute. For this reason, the technique was particularly well-suited to our objectives.

The study's technical data sheet.

| Universe | Consumers over 18 |

| Sample size | 427 consumers |

| Geographical scope | Regional – the Region of Extremadura (Spain) |

| Sampling | Non-probabilistic quota (gender and Province of residence) |

| Type of survey | Personal, self-administered |

| Fieldwork | February to June 2012 |

This technique was first used in the field of marketing in the mid-1970s (Green and Wind, 1975). Since then, it has been extensively applied to agri-food marketing to evaluate the importance of origin (Schnettler et al., 2008; Mesías et al., 2009; Font et al., 2011) and preferences for functional (Ares et al., 2010; Hailu et al., 2009; Johansen et al., 2010) and genetically modified foods (O’Connor et al., 2006; Cox et al., 2008). In financial marketing, it has been used to assess preferences for different types of credit cards and other financial products (Kara et al., 1996; Clark-Murphy and Soutar, 2005; Baheri et al., 2011; Mishra and Bisht, 2013), but not for the selection of financial entities.

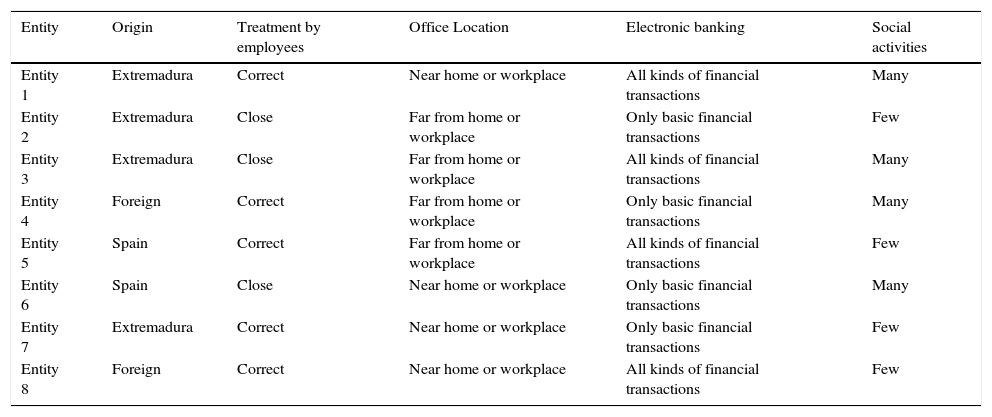

For the Conjoint Analysis, we used the full-profile method. In this, the respondent is presented with a single set of stimuli to evaluate. In the present case, each stimulus consisted of information about all 5 of the attributes included in the study. The number of stimuli used in the full-profile method depends on the number of attributes and their levels. There were 48 possible stimuli in the present case. Since such an overload of information would have adversely affected the quality of the responses, we carried out an orthogonal design to reduce the combinations to a subset of just 8 (Table 4). The respondents evaluated these 8 financial institutions by scoring them on a 9-point Likert scale (1=certainly would not choose; 9=certainly would choose). The parameters of the model were estimated by ordinary least squares multiple regression using the SPSS statistics computer programme package.

Stimuli presented to consumersa.

| Entity | Origin | Treatment by employees | Office Location | Electronic banking | Social activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entity 1 | Extremadura | Correct | Near home or workplace | All kinds of financial transactions | Many |

| Entity 2 | Extremadura | Close | Far from home or workplace | Only basic financial transactions | Few |

| Entity 3 | Extremadura | Close | Far from home or workplace | All kinds of financial transactions | Many |

| Entity 4 | Foreign | Correct | Far from home or workplace | Only basic financial transactions | Many |

| Entity 5 | Spain | Correct | Far from home or workplace | All kinds of financial transactions | Few |

| Entity 6 | Spain | Close | Near home or workplace | Only basic financial transactions | Many |

| Entity 7 | Extremadura | Correct | Near home or workplace | Only basic financial transactions | Few |

| Entity 8 | Foreign | Correct | Near home or workplace | All kinds of financial transactions | Few |

The questionnaire also included questions on variables that the literature has identified as antecedents or moderators of the place-of-origin effect. In particular, these were familiarity with the product category (financial products), familiarity with the products of the place (financial institutions in the region), the level of ethnocentrism, and sociodemographic variables. To measure the level of ethnocentrism, we used the 17-item CETSCALE, which has been validated in many contexts and situations (Klein et al., 1998; Samiee et al., 2005; Moon and Jain, 2002; Dmitrovic et al., 2009; among many others).

The questionnaire's content and measurement validity was confirmed based on expert judgement. In particular, a panel of seven academic specialists in marketing gave their favourable opinion on the construction of the questionnaire and the measurement of the variables. In addition, a small pilot test of 12 customers was carried out before launching the final study.

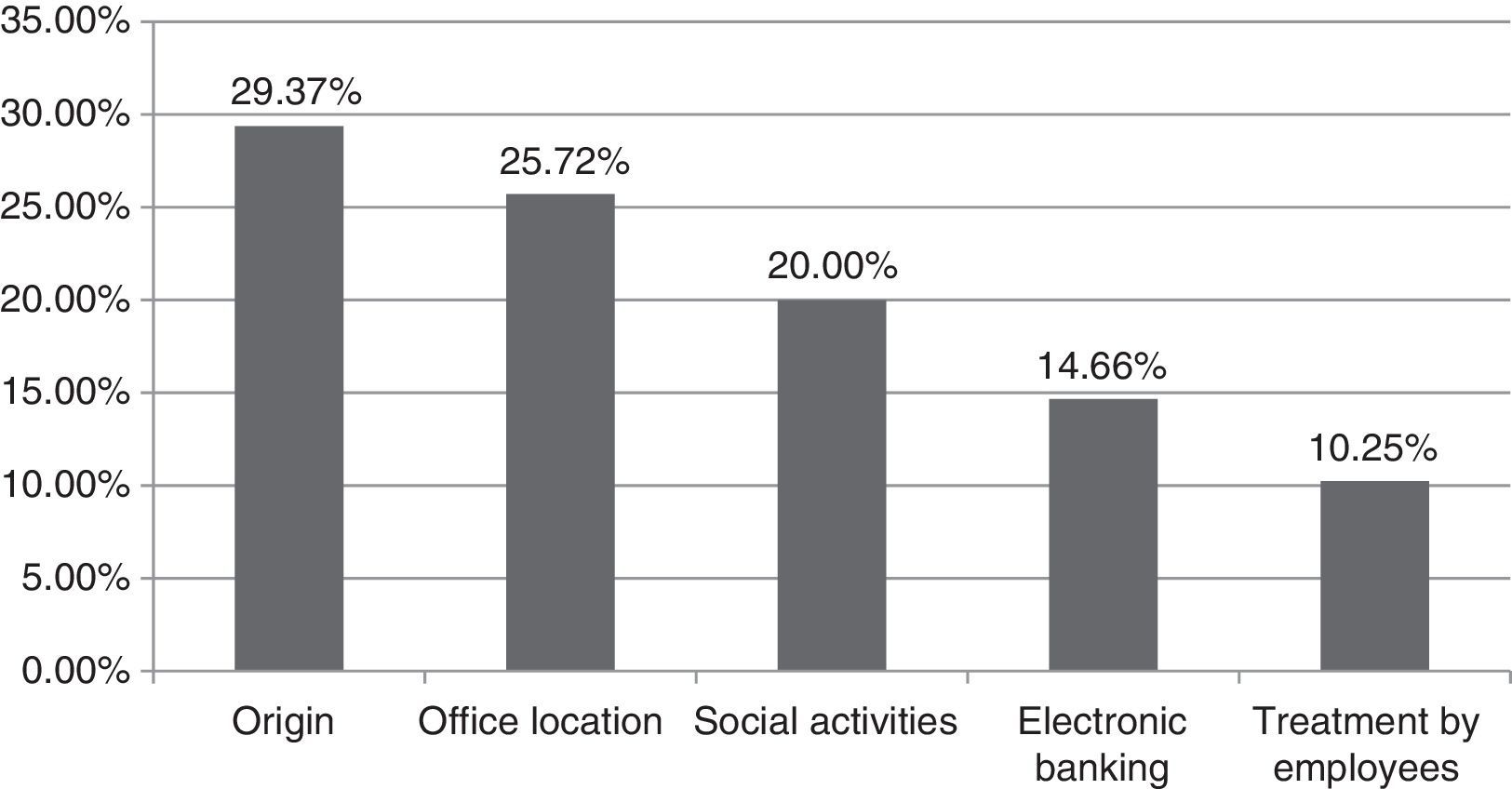

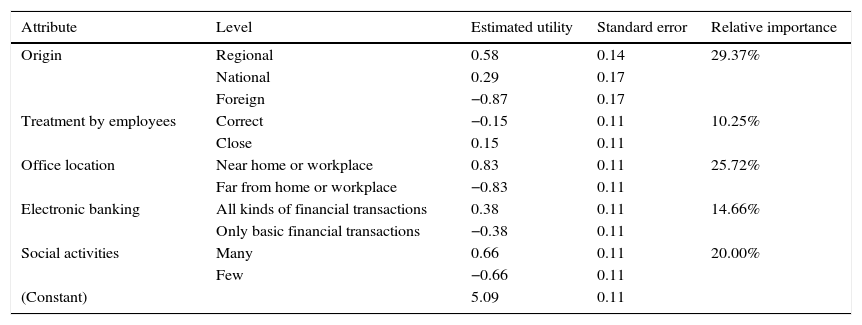

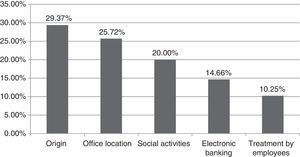

ResultsThe scores given by the respondents to the 8 proposals of financial institutions were used to estimate the utilities the respondents were implicitly assigning to the levels of the attributes considered in the model (Table 5), and thus the relative importance of those attributes (Fig. 1). The reliability of the model was assessed through Pearson's R and Kendall's tau statistics. Both indicators measure the correlation between the utilities expressed by the individuals and those predicted by the model. As both indicators reached values that were close to 1, it can be assumed that the model fits correctly.

Estimated utility of each level of the attributes.

| Attribute | Level | Estimated utility | Standard error | Relative importance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Regional | 0.58 | 0.14 | 29.37% |

| National | 0.29 | 0.17 | ||

| Foreign | −0.87 | 0.17 | ||

| Treatment by employees | Correct | −0.15 | 0.11 | 10.25% |

| Close | 0.15 | 0.11 | ||

| Office location | Near home or workplace | 0.83 | 0.11 | 25.72% |

| Far from home or workplace | −0.83 | 0.11 | ||

| Electronic banking | All kinds of financial transactions | 0.38 | 0.11 | 14.66% |

| Only basic financial transactions | −0.38 | 0.11 | ||

| Social activities | Many | 0.66 | 0.11 | 20.00% |

| Few | −0.66 | 0.11 | ||

| (Constant) | 5.09 | 0.11 |

Pearson's R=0.999; Kendall's tau=1.000.

The results showed that, for the sample as a whole, the preferred financial institution would be a regional entity, with close, personalized treatment on the part of its employees, with offices located close to the customer's home or workplace, with a Website allowing a broad range of financial operations to be done online, and that invests in many social activities within the region. This profile of the “ideal” financial institution conformed to expectations except for the origin, for which there was uncertainty about customer preferences before starting the study.

With respect to the relative importance of each attribute in the formation of customer preferences, the most important for the overall sample was the origin of the financial institution, with a relative weight of 29.4%. This was closely followed in importance by the location of the offices (25.7%), then the entity's social activities in the respondent's region (20%), the characteristics of the entity's electronic banking (14.7%), and finally the treatment by employees (10.25%). These results therefore corroborate hypothesis H1 since, under equal financial conditions, the origin is the most important of the five attributes for consumers when forming their preferences. The utilities estimated for each level of this attribute (Table 5) corroborate hypothesis H2, since a regional origin of the financial institution is preferred over national, and this over foreign.

Considering that respondents rated the 17 items of the CETSCALE with a score between 1 and 7 (minimum possible score of 17, maximum of 119), we set three, roughly equal length, levels of ethnocentrism:

- •

Customers who scored 51 points or lower conformed the low ethnocentricity segment, accounting for 35% of the sample.

- •

Customers who scored from 52 to 85 points conformed the medium ethnocentricity segment, accounting for 53% of the sample.

- •

Customers who scored 86 points or higher conformed the high ethnocentricity segment, accounting for 12% of the sample.

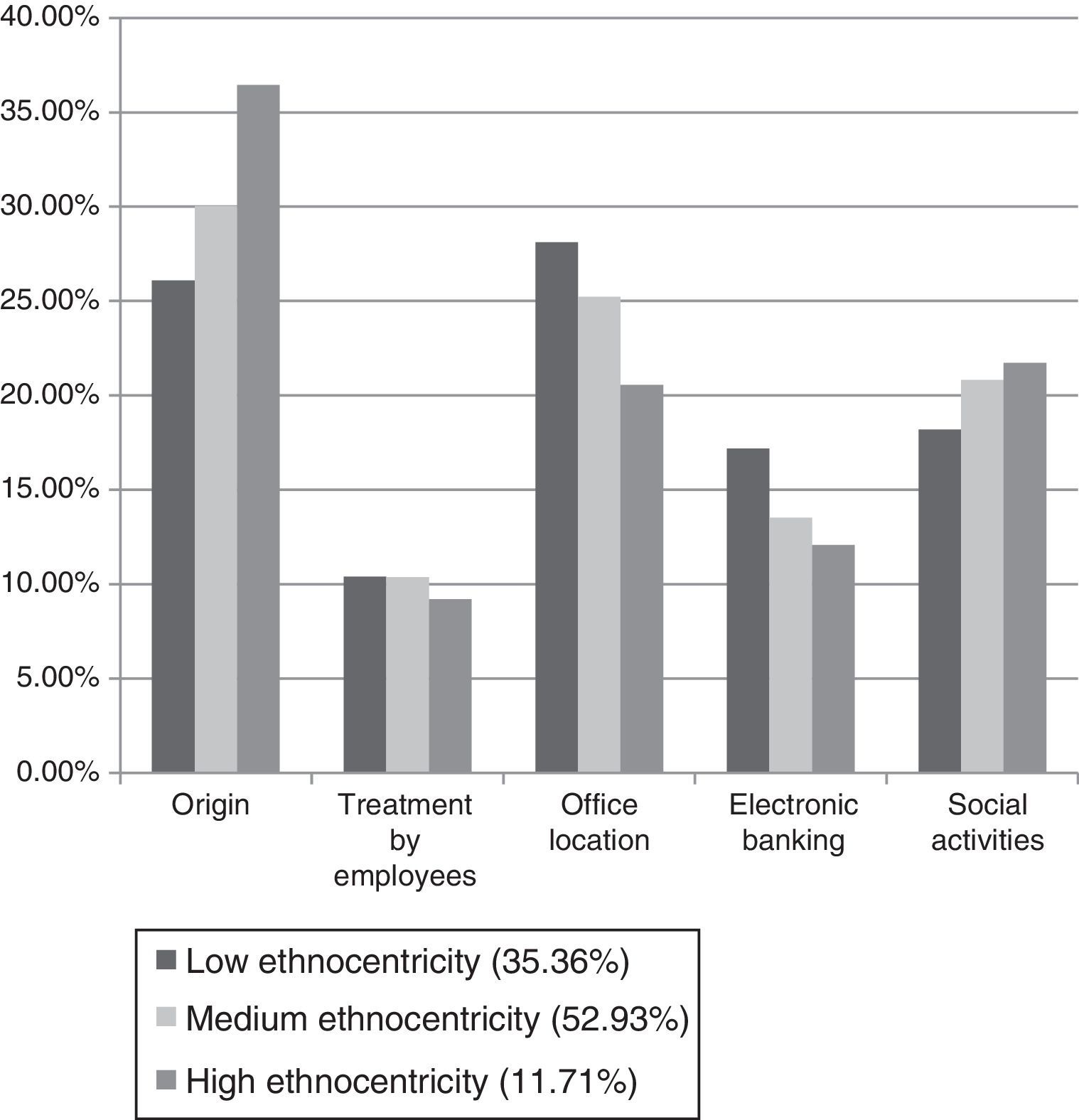

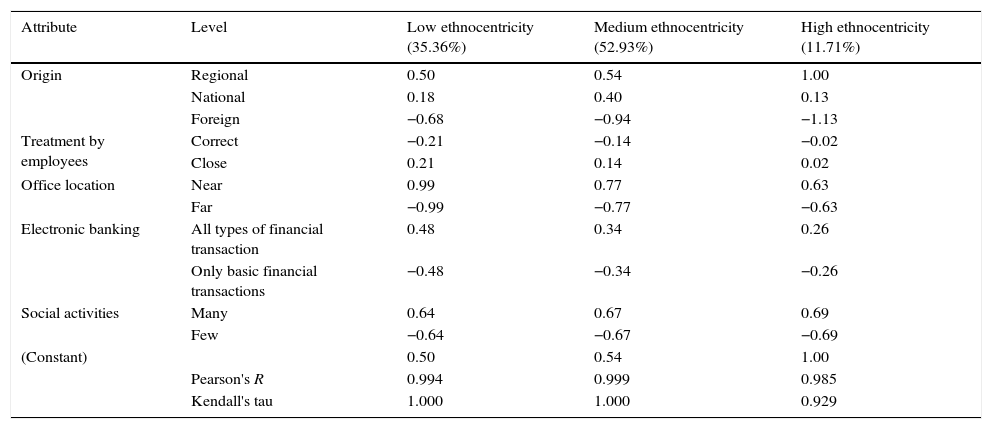

Fig. 2 and Table 6 present comparisons of these ethnocentricity segments for the relative weights of the attributes and for the utilities implicitly assigned to the different levels, respectively.

Utility estimates by segment of ethnocentricity.

| Attribute | Level | Low ethnocentricity (35.36%) | Medium ethnocentricity (52.93%) | High ethnocentricity (11.71%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Regional | 0.50 | 0.54 | 1.00 |

| National | 0.18 | 0.40 | 0.13 | |

| Foreign | −0.68 | −0.94 | −1.13 | |

| Treatment by employees | Correct | −0.21 | −0.14 | −0.02 |

| Close | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.02 | |

| Office location | Near | 0.99 | 0.77 | 0.63 |

| Far | −0.99 | −0.77 | −0.63 | |

| Electronic banking | All types of financial transaction | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.26 |

| Only basic financial transactions | −0.48 | −0.34 | −0.26 | |

| Social activities | Many | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.69 |

| Few | −0.64 | −0.67 | −0.69 | |

| (Constant) | 0.50 | 0.54 | 1.00 | |

| Pearson's R | 0.994 | 0.999 | 0.985 | |

| Kendall's tau | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.929 |

The low ethnocentricity segment is characterized by giving greater importance to the location of the offices (28.1%) than to the other attributes, with the origin of the entity being in second place (26.1%). Following these two are the entity's social activities (18.2%), electronic banking (17.2%), and the treatment by employees (10.4%). As one observes in Table 4, this segment prefers regional over national and foreign entities, and indeed this last has a negative utility.

The segment with a medium level of ethnocentricity is characterized by giving greater importance to the origin than did the previous segment. In particular, the origin is the most important attribute (30.0%), followed by the location of the offices (25.2%), social activities (20.8%), electronic banking (13.5%), and the treatment by employees (10.4%). Again, its members prefer regional over national entities, and these over foreign.

Finally, the segment with a high level of ethnocentricity gives a very high relative importance to the origin of the entity (36.4%), markedly above the other attributes. Social activities are the second most important attribute (21.7%), with the location of the offices following closely (20.6%). Finally come electronic banking (12.1%) and the treatment by employees (9.0%). Again, these customers prefer regional entities to national and foreign. There stands out the finding that the estimated utility of a regional origin for this segment is equal to unity, a value much higher than in the low and medium ethnocentricity segments (0.5 and 0.54, respectively). These customers’ preference for a regional origin is therefore very much stronger than that of the customers of the other two segments.

These results confirm the hypotheses H1 (in two of the three segments) and H2 (in all the segments). Furthermore, H3 is confirmed in that the level of relative importance given to the origin increases with increasing ethnocentricity of the customers. Finally, H4 is also confirmed in that the preference for regional over national and foreign entities increases with increasing ethnocentricity of the customers.

After this analysis of the preferences of the three segments, we did the corresponding chi-squared tests to determine the profile of the persons conforming them. The results for most of the variables were significant. The exceptions were household income and familiarity with the region's financial institutions.

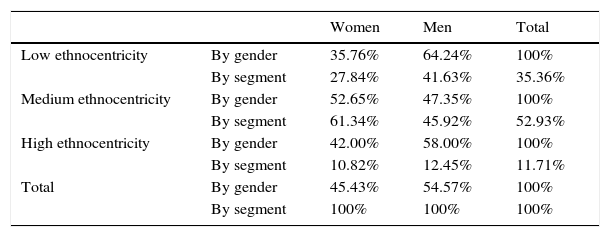

Regarding gender, the chi-squared value showed the differences between groups to be significant at the 1% level. One observes in Table 7 that the segment of low ethnocentricity is primarily made up of men (64.2%). The medium ethnocentricity segment, however, is fairly evenly distributed, although with a slightly greater proportion of women. Finally, the less numerous high ethnocentricity segment comprises a greater proportion of men than of women.

Contingency table by gender.

| Women | Men | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low ethnocentricity | By gender | 35.76% | 64.24% | 100% |

| By segment | 27.84% | 41.63% | 35.36% | |

| Medium ethnocentricity | By gender | 52.65% | 47.35% | 100% |

| By segment | 61.34% | 45.92% | 52.93% | |

| High ethnocentricity | By gender | 42.00% | 58.00% | 100% |

| By segment | 10.82% | 12.45% | 11.71% | |

| Total | By gender | 45.43% | 54.57% | 100% |

| By segment | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Pearson's chi-squared=0.005.

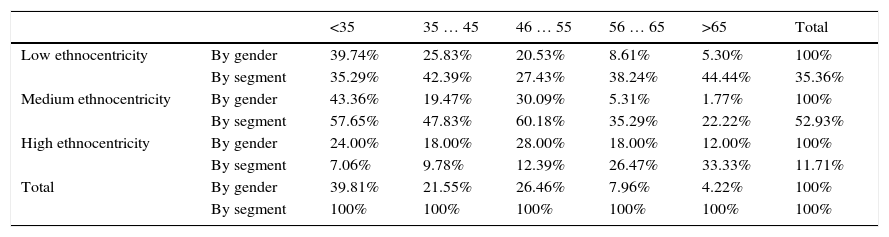

In regard to age, the chi-squared values again showed the differences to be significant at the 1% level. In Table 8, one observes that the low ethnocentricity segment is mainly made up of persons of up to 55 years in age. Specifically, most are under 35. The medium ethnocentricity segment is formed mainly of persons under 35 and between 46 and 55. Finally, the high ethnocentricity segment is mainly composed of people under 35, but it is also characterized by having the greatest percentage of older persons, with 30% of the members of this segment being 56 or older. One can say, therefore, that highly ethnocentric people are on average older than those with lower levels of ethnocentricity. These results are consistent with those of earlier studies (Sharma et al., 1995; Watson and Wright, 2000; Luque et al., 2004).

Contingency table by age.

| <35 | 35 … 45 | 46 … 55 | 56 … 65 | >65 | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low ethnocentricity | By gender | 39.74% | 25.83% | 20.53% | 8.61% | 5.30% | 100% |

| By segment | 35.29% | 42.39% | 27.43% | 38.24% | 44.44% | 35.36% | |

| Medium ethnocentricity | By gender | 43.36% | 19.47% | 30.09% | 5.31% | 1.77% | 100% |

| By segment | 57.65% | 47.83% | 60.18% | 35.29% | 22.22% | 52.93% | |

| High ethnocentricity | By gender | 24.00% | 18.00% | 28.00% | 18.00% | 12.00% | 100% |

| By segment | 7.06% | 9.78% | 12.39% | 26.47% | 33.33% | 11.71% | |

| Total | By gender | 39.81% | 21.55% | 26.46% | 7.96% | 4.22% | 100% |

| By segment | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Pearson's chi-squared=0.000.

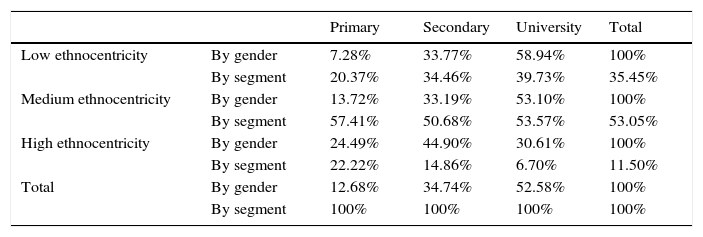

With regard to education, the differences are significant at the 1% level (Table 9). Both the low and the medium ethnocentric segments are mainly made up of university graduates and persons with post-graduate degrees. The highly ethnocentric segment is characterized by having a greater number of persons with up to primary or secondary education, so that one can say that the highly ethnocentric segment has a lower level of education than do the other two segments. Again, this result is consistent with those of earlier studies (Sharma et al., 1995; Watson and Wright, 2000; Luque et al., 2004).

Contingency table by education level.

| Primary | Secondary | University | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low ethnocentricity | By gender | 7.28% | 33.77% | 58.94% | 100% |

| By segment | 20.37% | 34.46% | 39.73% | 35.45% | |

| Medium ethnocentricity | By gender | 13.72% | 33.19% | 53.10% | 100% |

| By segment | 57.41% | 50.68% | 53.57% | 53.05% | |

| High ethnocentricity | By gender | 24.49% | 44.90% | 30.61% | 100% |

| By segment | 22.22% | 14.86% | 6.70% | 11.50% | |

| Total | By gender | 12.68% | 34.74% | 52.58% | 100% |

| By segment | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Pearson's chi-squared=0.003.

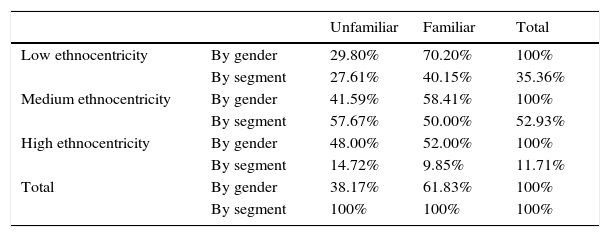

Finally, the contingency table results for the level of familiarity with the product category, i.e., knowledge of the financial system, show significant differences (at the 1% level) between the three ethnocentricity segments. As one observes in Table 10, the low ethnocentricity segment is clearly formed by persons familiar with the financial system, and the medium ethnocentricity segment also contains a greater proportion of customers with a high level of familiarity with these services. In contrast, the highly ethnocentric segment has an even distribution of customers both familiar and less familiar with the financial system. One can thus say that as the customers’ level of ethnocentricity decreases, their level of familiarity with the product category increases. These results are consistent with the theory of the Halo Effect and Summary Effect of Han (1989), and are in line with the results of previous studies such as those of Maheswaran (1994) and Jiménez and San Martín (2010), works which find that the greater is the familiarity with or knowledge about a product, the less the influence of information about its origin.

Contingency table by familiarity with the financial system.

| Unfamiliar | Familiar | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low ethnocentricity | By gender | 29.80% | 70.20% | 100% |

| By segment | 27.61% | 40.15% | 35.36% | |

| Medium ethnocentricity | By gender | 41.59% | 58.41% | 100% |

| By segment | 57.67% | 50.00% | 52.93% | |

| High ethnocentricity | By gender | 48.00% | 52.00% | 100% |

| By segment | 14.72% | 9.85% | 11.71% | |

| Total | By gender | 38.17% | 61.83% | 100% |

| By segment | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Pearson's chi-squared=0.003.

This study has sought to extend the broad literature on the place-of-origin effect in the field of consumer goods by considering regions and the services sector. The results have confirmed the importance of the origin relative to other attributes as an element that the client uses to select their usual financial institution, always under the provision that the financial conditions offered are similar. This finding is in line with studies in other sectors, such as Ahmed and d’Astous (1996, 1999), Martínez-Carrasco et al. (2006), and Monjardino and Ventura (2001). In addition, a positive region-of-origin effect was confirmed since the average customer prefers regional entities to national or foreign, consistent with the findings of such previous studies as those of Bernabéu and Tendero (2005), Gil and Sánchez (1997), Fotopoulos and Krystallis (2003), Tendero and Bernabéu (2005), Chocarro et al. (2009), Font et al. (2011), Claret et al. (2012), and Realini et al. (2013).

Another conclusion is that customers’ level of ethnocentricity influences their preference structure. The more ethnocentric individuals attach greater importance to the origin of the financial institution, and, of course, assign greater utility to regional as against national or foreign origin. The fact that even the segment with the lowest level of ethnocentricity prefers entities with a regional origin confirms the argument of Sharma et al. (1995) that the effect of consumers’ ethnocentrism on their attitudes should be greater in the case of products that are unnecessary or constitute a threat to the local economy, as could be the case at present due to the economic crisis. The characteristic profiles of the customer segments according to their level of ethnocentricity coincide with the bulk of previous studies analysing the characteristics of ethnocentric consumers (e.g., Sharma et al., 1995; Watson and Wright, 2000; Luque et al., 2004).

In a study of this type it is important to emphasize the value of transferring the knowledge to the business sector. In the present case, the international economic and financial crisis has had a major negative impact on Spain, forcing it to restructure its financial system. Savings banks and credit unions represent more than half of the sector and usually have a regional scope of action. Most of them have been forced to undertake processes of integration to improve their solvency and competitiveness. These processes can be through mergers and acquisitions or through a specific figure known as a SIP. In the former case, the decision usually involves the creation of a bank and the loss of linkage to the region-of-origin of the integrated entities. In the latter case, such a loss does not necessarily occur. From a marketing and brand management point of view, regional financial institutions that are in the process of integrating with competitors should consider whether to keep their regional brand and enhance communication in this regard, or instead opt for a single common brand for all the regions in which they compete. The results of the present study constitute clear evidence in favour of the first option as brand strategy. However, this information on bank customer behaviour should be weighed against other strategic and political aspects of financial institutions, such as their geographic expansion policies, the cost cutting deriving from potential economies of scale, and their possible repositioning once the economic crisis is over, especially in cases in which they have been associated with poor management, financial problems or even rescued with public funds from the government.

In addition, the study identified the existence in the region of a segment of highly ethnocentric customers, a segment with a well-defined profile. This segment can be readily attended to by Extremadura's financial institutions through a good communications strategy aimed at their particular needs and characteristics. The characteristics of the segments also mean that financial institutions’ marketing managers should be able to use commitment and relationship with the region as a means to access these three types of customers, and to differentiate and position themselves against the competition.

One limitation of the study is that the results are not directly extrapolatable to other geographical areas. The behaviour of clients and consumers with respect to local, regional, and national products can vary considerably depending on each region or country's political and historical conditions, as do such variables as ethnocentrism, regional sentiment, and the reputation accorded to the products’ place-of-origin. In addition, as has been established in the literature, the place-of-origin effect varies from one product category to another.

We believe, however, that the present work also opens up new alternatives for future research. Examples might be analysing whether the region-of-origin effect in the financial sector is similar for other regions, evaluating the place-of-origin effect in other service categories, or conducting cross-temporal studies to determine whether individuals’ levels of regional ethnocentricity change over time according to the circumstances of their environment.